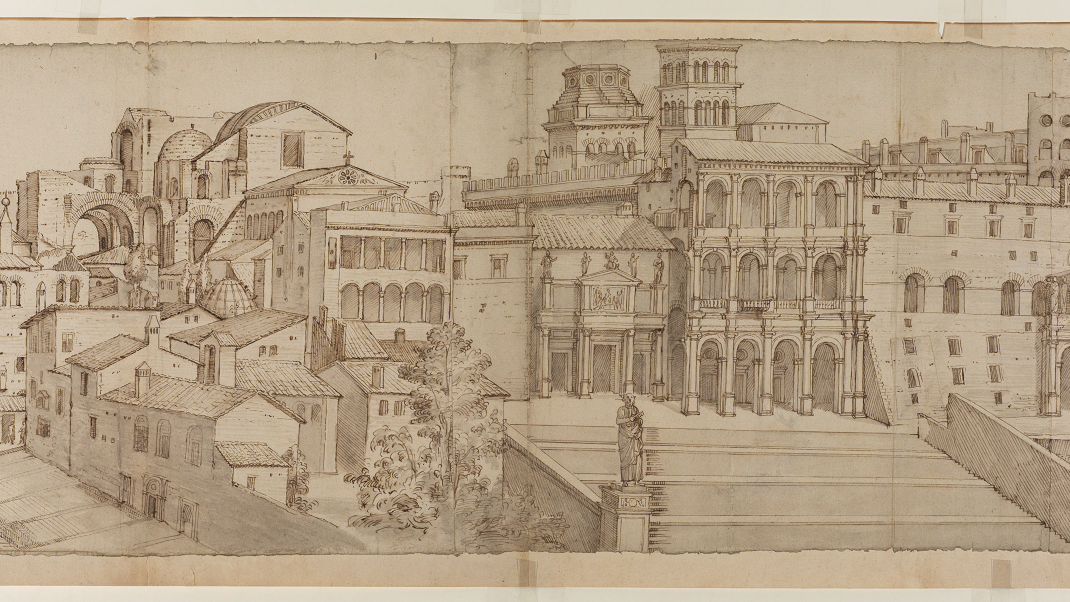

Cat. 1: View of St Peter’s

This view of Saint Peter’s basilica is testimony to the fascination and attraction that Rome exerted on European artists in the mid-sixteenth century. Presumably executed in a workshop far from the papal city, the drawing combines studies of the basilica with various architectural projects that were planned but never built, such as the tower at left. Although not entirely based on observation, this panorama nonetheless evokes the experience of the wonders of the Eternal City.

Views of Rome became increasingly frequent in the sixteenth century as papal patronage transformed the city into an undisputed artistic centre. Artists flocked to the Eternal City from all over Europe in order to study the revolutionary works of masters such as Raphael and Michelangelo and the antiquities which could be seen in the open air in public spaces and in private collections. Pietro Bembo, in his Prose della volgar lingua (Writings on the Vulgar Tongue), published in 1525, wrote about the pilgrimage of artists to Rome to study “the beautiful figures in marble and sometimes of bronze, which are either scattered around the city here and there and lay on the ground, or are publicly and privately preserved and kept as treasures, and the arches, baths, theatres and various others buildings, which in part still stand.”

Some of the most famous views of Rome are those produced by the Dutch painter Maarten van Heemskerck, who visited the Eternal City in the mid-1530s. He made exquisite drawings in pen of ancient marbles and monuments, but also paid close attention to the basilica of St Peter’s, then a gigantic, if half-abandoned building site, which echoed the ancient ruins scattered throughout the city.

One of van Heemskeerck’s drawings depicts the basilica’s front, facing the piazza of St Peter and its surroundings (see fig. 1). His study offers a useful point of comparison for the present drawing which, at first glance, appears to represent the same view. Van Heemskerck’s coherent and precise depiction of the church’s façade seems to be based on direct observation and thus presumably to be a dependable image to reconstruct the appearance of the site around 1535. In contrast, the drawing on display, for all its apparent similarities to the Van Heemskerck view, is not a reliable view made from life. Rather, it is an assemblage which must have been put together from a variety of earlier studies. The artist responsible for this drawing has indulged in an unusual fantasy, turning ephemeral projects or rejected designs into what appear to be permanent features of the church complex as he envisions it.The elaborate classical frontispiece that decorates the three main entrance doors to the basilica and here appears to be a permanent part of the structure, for instance, corresponds quite precisely with an ephemeral architectural invention by Antonio da Sangallo the Younger known through a drawing in the Uffizi (U112recto) and presumably realised on the occasion of the triumphal entry into Rome of Charles V in April 1536.[1] The same structure is nowhere to be found in Van Heemskerck’s drawing. Moreover, the Courtauld drawing shows that various architectural elements had been updated since the years in which van Heemskerck realized his view: the windows on the building to the right of the church entrance, for instance, which featured the old-style windows with the cross in the middle and have been replaced by more modern, open windows. In addition, the two storey loggia on the left of the façade was completed with a second trabeated level, whereas when van Heemskerck drew the structure when only one level had been completed.

Finally, the Courtauld drawing shows two bell towers behind the imposing Benediction Loggia at the centre of the façade, while all extant records agree that there was only one. On close observation, it becomes clear that the same tower was drawn twice. Whereas the one on the right featuring two levels of small rounded arches corresponds to that visible in other known views of the basilica, such as van Heemskerck’s drawing, the one on the left is unconvincingly connected to the rest of the building’s fabric and shows features, like the round oculi on the octagonal drum on top of it, which recall Sangallo’s unexecuted project for St Peter’s of around 1540, as we know it from the grandiose wooden model, preserved in the Vatican.

These details suggest that the Courtauld drawing must postdate Antonio Sangallo’s designs for the new St Peter. In relation to the elusive problem of dating the drawing on display, two further elements need to be taken into consideration. The first concerns the level of completion of the colossal structure of the basilica visible in the background. In comparison with van Heemskerck’s drawing of the mid 1530s, by the time the Courtauld drawing was executed the construction of the main body of the church had made substantial progress, as shown by the East and South transepts, which are represented as fully vaulted. This was approximately the stage which the new church’s construction had reached by the time of Sangallo’s death in 1546.

Since we do not see any trace of the cornice of the monumental drum conceived by Michelangelo after he took over the role of architect of the basilica in 1547, which was well visible by the mid-1550s as shown by two drawings dated to around 1557 appended to van Heemskercks’ sketchbook in Berlin, we should conclude that the Courtauld drawing must record a stage in the basilica’s construction dating from between the mid-1540s and the mid-1550s.[2] In any case, it must predate 1564, when Michelangelo died after seeing the drum completed. This stage of construction is well illustrated by an engraving by Etienne Dupérac published by Antoine Lafrery around 1570 (see fig. 2).

The Medici coat of arms which appears under a canopy supported by telamons on top of the portal of the papal palace to the right of the church further unsettles our assumptions about the drawing’s date, because it would seem to indicate that the view was executed during the reign of a Medici pope, either Clement VII (1523-1534), or Pius IV, Giovanni Angelo Medici, who reigned from 25 December 1559 until his death in 1565. However, the considerations made above and the fact that during Pius IV’s pontificate the drum of the church would surely have been well visible, ensure us that the drawing doesn’t date from the time of any of these two popes.

All this suggests that the artist responsible for this monumental drawing had been to Rome and knew of a variety of projects for St Peter, especially those of Sangallo, yet executed this drawing at a temporal and geographic remove, introducing a degree of fantasy which may have made his study all the more appealing to his audience. A further indication that this may have been the case is provided by a detail to the right of the papal palace, on the extreme right of the drawing. Whereas both in Van Heemskerck’s drawing and in Duperac’s engraving we see in that area a conspicuous and solid wall with a round portal, in the Courtauld drawing the wall is absent and the very nature of the terrain appears ambiguously represented, as if the artist did not know exactly how to represent that area. In that lateral section of the drawing, the three levels of Logge are unusually fully visible, while in other representations they are partly covered by other buildings. Moreover, underneath the Logge we see two smaller buildings awkwardly positioned on a platform resting on a wall perched by a colossal arch, the aspect of which makes one suspect that it is an element derived from some ancient building seen elsewhere or invented outright and inserted there by the artist to fill a space for which he either did not have any visual evidence, or which he did not remember.

The fact that the drawing’s paper contains a watermark typically used in the Flanders in the third quarter of the sixteenth century reinforces the possibility that this illusionistic panorama was executed by a Flemish artist, possibly after his return from a formative trip to Italy, combining elements from different sources to produce a hybrid work that recorded and subtly manipulated one of the most important sites of Christianity.

GR

Footnotes

[1] A further visual testimony of Sangallo’s project for this triumphal arch is contained in another drawing at Chatsworth, sometimes attributed to van Heemskerck himself, but executed later than the work at Vienna, which shows the same frontispiece that we see in the Courtauld drawing.

[2] For the history of the construction of St Peter’s drum, see Vitale Zanchettin, “Il tamburo della cupola di San Pietro”, in Michelangelo architetto a Roma disegni della Casa Buonarroti di Firenze, exhib. cat., eds M. Mussolin and P. Ragionieri, Cinisello Balsamo (Mi), Silvana editoriale, 2009, pp. 180-199.