FOCUS: Drawing The Human Figure

Devised by Francesca Herrick and Nadine Mahoney

Download the PDF: Drawing the Human Figure

Introduction

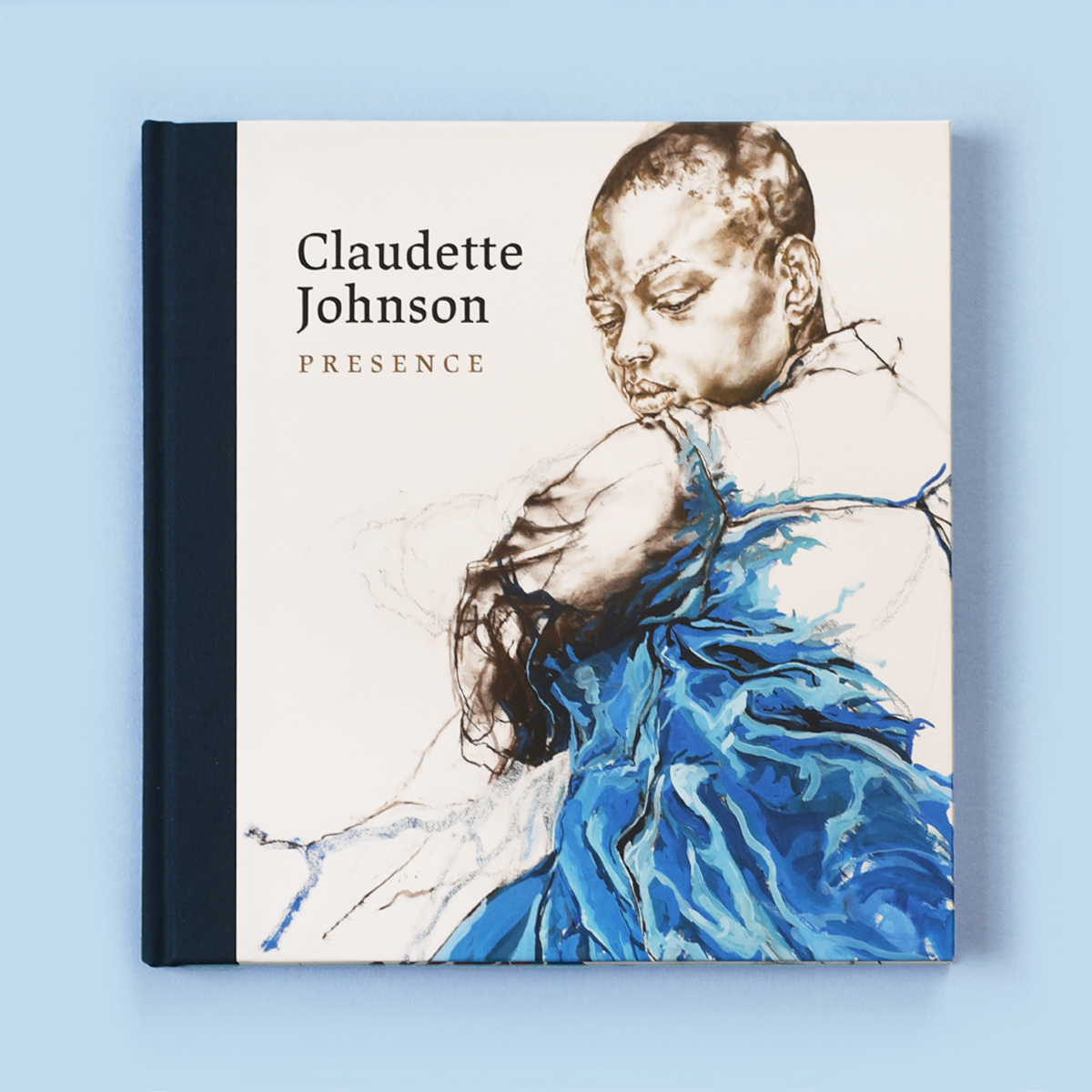

The larger-than-life drawings of Claudette Johnson (b. 1959) offer a fantastic opportunity to explore the power of line, colour and scale for capturing the human figure. London-based Johnson is best known for her pictures of Black women, which typically show the sitter pushing up against or beyond the boundaries of the paper. The women appear confident and comfortable with their identities, although some of their poses might have been difficult to hold. Whether looking at the works in person, or with our virtual tour, you can see that the people in her artworks have a strong presence in the gallery space. They feel close and real.

Artworks such as Figure in Blue show an intimate moment, despite the large size of the paper. Johnson spends a lot of time with the sitters and ‘invites them to take up space in a way that is reflective of who they are.’ This makes the artworks a collaboration. There is often a strong sense of individuality, but the artwork titles never record a name, or indeed any reference to time and place. Johnson’s drawings of the human figure invite people to connect their own emotions and experiences, especially people who have been excluded from art historical discourse. At the same time, Johnson’s work is rooted in art history, continuing to develop the way other artists have broken new ground when depicting the human figure.

Talking Points 1

- What makes a picture of a person a portrait? Come up with some ideas and then check if Johnson’s drawings fit your definition/s.

- Looking at Figure in Blue, what human qualities do you think Johnson wanted to show? Write down three words.

- What is a drawing? Please think about materials, line, colour and the space of the paper. Come back to this question once you have tried the activities below.

Speaking out and challenging art history

‘The fiction of “blackness” constructed by and through colonialism and its aftermath can be interrupted by an encounter with the stories that we have to tell about ourselves.’

Claudette Johnson

Johnson’s drawings contest and provide compelling alternatives to historical European depictions of Black women in art. She describes their presence in art as one that has been ‘distorted, hidden and denied,’ referring to examples where a Black model was used to provide an aesthetic contrast to the white subject of the painting (for example, Édouard Manet’s Olympia, 1863). She also highlights the long tradition of exoticising and eroticising women of colour, evident in the work of Paul Gauguin (1848-1903). Such approaches deny the context and humanity of the original sitters. In reality, the women represented would have already felt little control over their bodies as a result of colonialism and racism.

In a now legendary talk given at The First National Black Art Convention in Wolverhampton (1982), Johnson, aged just 23, discussed the marginalisation of Black women in European art and offered her own practice as a challenge to historical depictions produced for the colonial male gaze. She was heckled as men in the audience failed to appreciate significant differences between the historical examples presented and her drawings. The conference organisers side-lined Johnson to a separate room to continue the discussion. A positive outcome was meeting artists Sonia Boyce (b. 1962), Lubaina Himid (b. 1954) and Ingrid Pollard (b. 1953), women who would become similarly influential in the Black British Arts Movement.

Telling a different story of Black presence

In order to give her sitters powerful physical and psychological presence, Johnson borrows visual strategies from across art history, with references as diverse as Raphael (1483-1520), Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901), Suzanne Valadon (1865-1938), Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), Egon Schiele (1890-1918) and Jenny Saville (b. 1970). As a student at Wolverhampton Polytechnic between 1979-82, Johnson’s passion for art history was often frustrated by a lack of access to positive imagery of Black women. She developed an approach of taking subject matter from found images and photographs of herself, of models and from her imagination. The emotional presence of the artworks comes from giving the Black sitters visibility and control that has historically been denied.

‘I feel that the active involvement of the women in my drawings, who are so obviously engaged in creating themselves, acts to challenge the entrenched passivity and negative sexuality of the “nude” tradition in painting.’

Claudette Johnson

The beautiful materiality of Johnson’s drawings can perhaps distract us from the truly political nature of her art and her ongoing commitment to breaking boundaries, both visually and intellectually. Her practice addresses uncomfortable histories and confronts significant absences, while also offering the space for productive conversations. She graduated at a crucial time of Black political activism and her works from across the decades remain just as relevant in our own era of protest. She continues to draw Black women subjects who refuse to be contained or objectified. In recent years, she has also turned her attention to young Black men and their subject-hood in art, sometimes using her sons as models.

‘[A]reas of detail are concentrated around solid areas of emptiness making the absences as significant as what is present. It is a way of looking at the damage that has been done to us. Some of the ghosts of displacement and unbelonging are exorcised in the process.’

Claudette Johnson

Talking Points 2

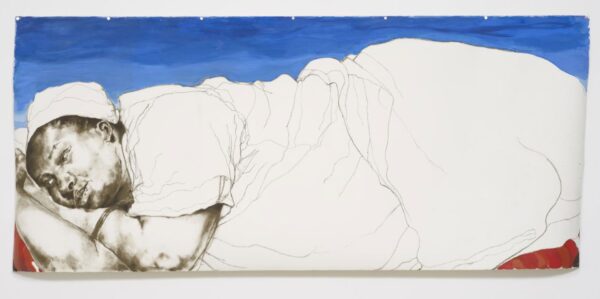

- Compare and contrast the depiction of the female body in Johnson’s Reclining Figure (2017) with Gauguin’s Nevermore (1897).

- Johnson is consciously inserting her drawings into a canon of art historical imagery. Discuss the qualities of her work (colour, scale, composition, etc.) that give her works presence in a gallery context.

- What recent events could have motivated Johnson to include Black male subjects in her art? What issues surround the depiction of the Black male body versus the Black female body?

The magic of drawing

‘I want to find out something about drawing – and about the history of drawing – how light and dark sit together.’

Claudette Johnson

Johnson’s artworks push us to think about the exciting possibilities of drawing for our own work. She is part of a long line of artists who have been brave enough to approach a blank page with an open mind and see where lines will lead. She readily admits to often ‘making a mess’ and that most of her experimenting comes from a place of ‘not knowing’. Johnson recognises a similar freedom in drawings by Rembrandt (1606-1669), a Dutch artist who lived 400 years ago. He is famous for his thoughtful portraits, often made using few colours with strong contrasts of light and dark. His Man Seated in The Courtauld Collection has similarities with Johnson’s work – the figure may be calm and composed, but the layered and tangled lines bring incredible energy.

‘That is something magical about drawing anyway isn’t it? The coming into being of a figure on a flat surface, there is always something magical about that. Pencil drawing, and even charcoal, has the capacity to be quite delicately delineated and diffused. But there is a boldness, maybe even crudeness, to some of the marks you can make with pastels …’

Claudette Johnson

Art Activities

Johnson’s large-scale artworks require physical as well as creative energy. When she works in her studio, she begins with some warm-up drawings that she describes as ‘the equivalent of scales practice for a pianist’. She says they allow her to work freely, but also encourage deep concentration. Try these activities and see how your drawing style and mood change.

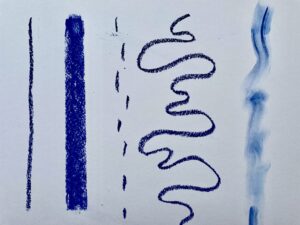

Activity 1: Warm-up drawing

Materials: coloured chalk, A4 paper (any paper, although cartridge paper will achieve the best results)

- Using a single piece of coloured chalk, create a thin continuous line that runs from the top of the page to the bottom.

- Create a thick, continuous line using the chalk sideways. Take your time – Johnson’s drawings are never rushed. Embrace smudges and rough edges since it’s partly the special texture of chalk that gives Johnson’s drawings a presence.

- Create a broken line.

- Create a wavy line.

- Using the chalk on your fingers, create as many marks as you can. One of the qualities that Johnson likes about pastels is how they record fingerprints, which she calls a ‘memory of my mark.’

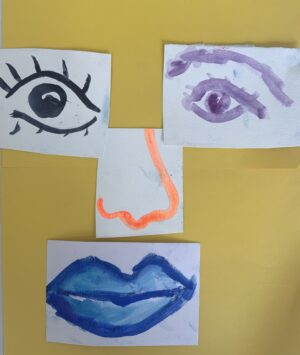

Activity 2: Warm-up drawing

Materials: pieces of A6 paper, watercolour paints, water pots, brushes

- In small groups of 4 students, each person paints one feature from another person’s face.

- Don’t look at your neighbour and paint a single feature, pick from: left eye / right eye / mouth / nose. You have 5 minutes to do this.

- Bring the features together onto a single sheet of paper to create a face.

Activity 3: Artist and model

Materials: chalks and pastels, large sheets of paper

Working in pairs, take it in turns to be the artist and the model.

Spend 10 minutes drawing the pose and then swap roles.

Artists:

- Ask your model to choose a pose and demonstrate it.

- Ask them why they chose it?

- What does the pose say about their identity or character?

- How does it represent their emotions?

- What background would you use? Why?

Models:

- What are you trying to communicate through your pose? (think about your identity, character and emotions)

- How does it feel being the model?

- Is your pose easy or difficult to hold?

- What would you change if you knew it was going to last for several hours?

- What background and clothing would you choose to represent your identity?

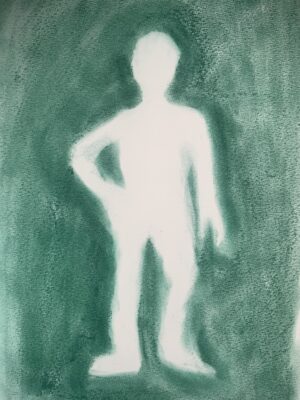

Activity 4: Drawing outside the lines

Materials: A4 paper, coloured chalk

- Working in pairs, have your partner stand and pose for you.

- Using the long side of the chalk, block out the space around them (the negative space).

- Take your time to think about the edges of their body, the gaps between their legs, space between their arms and their torso – try not to draw any lines!

- Blend the chalk with your fingers to make it a solid colour and reshape the contour of the body.

- Now that the background is a solid colour, can you see how the shape of the body feels more present?

- Swap places with your partner and pose for them.

Activity 5: Create a collage portrait

Use a mirror to draw your own face following these steps. This activity can also be adapted by using a photo, looking at a partner, or from your imagination.

Materials: chalk pastels, glue stick (PVA glue or masking tape would also work), collection of papers in varying sizes e.g. A6, A5, A4

- Collect a selection of papers.

- Select one piece and draw a nose in the middle of paper, trying to fill as much space as you can. Think about which lines from your warm-up would be best to use.

- Stick another piece under the nose and draw in the mouth.

- Add more pieces of paper for the eyes.

- Continue this process for the ears and chin.

- At this point, look at the drawing and think about identity: What does your hair look like, is it wavy or straight? Short/ long? Is there a hijab, hat, or can you see any significant jewellery?

- Add additional pieces of paper as you draw in the hair, neck and shoulders.

Activity 5: Extension

- Use different papers, coloured cards, music sheets, old photocopies, newspaper or magazines.

- Add more paper to depict the rest of the body.

Activity 6: Incorporate music

- Johnson has compared the broken lines of her drawings with jazz, where ‘the line gets broken and rearranged, and the rhythms syncopate, not following a pattern that is easily recognised, yet there is a pattern’.

- Listen to Johnson’s playlist

- Now listen to your favourite music as you do an activity.

These drawing activities also work well with the following artworks:

Experimental line

Have a look at Toulouse-Lautrec’s portrait Jane Avril as an example of the use of experimental line.

Negative space

Look at Edgar Degas (1834–1917), Dancer Looking at the Sole of her Right Foot, as an example of negative space.

Resource bibliography and useful links

Biography and recent works: Claudette Johnson – Hollybush Gardens

Watch Claudette Johnson talk about her artwork and influences, produced by Tate: Claudette Johnson – ‘Giving Space to the Presence of a Black Woman’ | Tate

Claudette Johnson, Audio recording of talk at the First National Black Art Convention, 1982. Online.

Claudette Johnson, ‘A Statement from the Artist’, in Pushing Back the Boundaries, exh. cat., Rochdale Art Gallery, 1990. Print.

Claudette Johnson, ‘Issues Surrounding the Representation of the Naked Body of a Woman’, Feminist Art News, vol. 3, no. 8, 1991. Print.

Claudette Johnson and Emma Ridgway, ‘I Came to Dance’, interview in Ridgway, ed., Claudette Johnson. I Came to Dance, exh. cat., Modern Art Oxford, 2019. Print.

Dorothy Price and Barnaby Wright, Claudette Johnson. Presence, exh. cat., The Courtauld Gallery, London, 2023. Print.