Devised by Fran Herrick

Download the PDF: Impressionism and Sensory Atmospheres

Introduction

Paintings by Monet and his artistic circle do not tell us precisely what a place looked like, but rather what it felt like to be there at a certain moment in time. Or, in the case of Manet’s Bar, perhaps combining several different moments. While Manet likes to hint at a story, others choose to abandon narrative altogether and just focus on mood. We might say that their works have a strong sense of atmosphere, but how can we talk about this?

Atmospheres are tricky to pin down – they are qualities of a space (sound, temperatures, textures etc.) sensed by us, often in just a fraction of a section, without necessarily thinking about it. In Art History we tend to look at artworks in terms of subject matter, composition (the arrangement of visual elements), how they were made and what was happening at the time. These are all important things to consider, but there is also much to be gained from slowing down and taking time to appreciate the ways in which a painting appeals to our different senses.

Capturing modern Paris

Édouard Manet was friends with the Impressionist group of artists, although he chose not to take part in their exhibitions. He lived in Paris all his life and witnessed huge changes to the city. The population grew from roughly three quarters of a million people in the 1830s to over two million by 1888, when he painted A Bar at the Folies-Bergère. New shopping arcades, boulevards (wide streets), parks and entertainment venues were developed to provide spaces of leisure for wealthy Parisians. The crowds, electric lighting and reflective surfaces in this painting were all part of the modern experience. Somewhere he would have visited in person, the Folie-Bergère is a music hall that remains open to this day.

What type of place do you think this is?

Can you spot the performer?

Who is the central figure? How would you describe her expression?

What do you think is happening in the mirror reflection behind her?

Do you notice anything unusual about this?

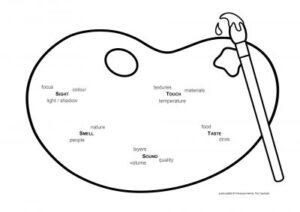

Step 1: Make a ‘senses palette’

Download and print the senses palette template, or draw your own version of this on a sheet of A4 paper.

Put yourself in the place of Manet’s barmaid.

It’s late in the evening, the venue is full and the performance is underway. You are separated from the crowds by the marble bar and lean on it slightly to steady yourself. You pause, just for a moment.

Use the senses palette to write down how people, objects and elements of the space appeal to each of your five senses (sight, smell, sound, taste and touch). Don’t worry about being neat – just note down whatever comes to mind as you look closely at the artwork. Aim for a mind-map effect. You can use nouns or verbs or a combination, e.g. clinking glasses, waxy oranges.

Step 2: Write a short poem

Use your senses palette to write a short poem that conveys the atmosphere of the Folies-Bergère fro the perspective of the barmaid. Imagine you are writing this for someone who has never seen the painting. Highlight word combinations that evoke a strong feeling or mood. You could start with a very simple format: I see…, I smell…, I hear… etc. for each line. Alternatively, you could structure your poem as a short story where the sensations of the space add drama to the encounter between the barmaid and her customer in the reflection, or perhaps she’s caught in a moment of daydreaming, where different impressions come in and out of focus.

There is no right or wrong answer. This activity is an experiment to see how a sensory experience, originally captured in brush marks, might be translated into words.

Supporting Material

Impressionism

The Courtauld Gallery has a world famous collection of Impressionist paintings, including some early works by Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Camille Pissarro. These Impressionists were a group of thirty artists who put on their own art exhibition in Paris in 1874 (the first of eight). They had repeatedly had their work rejected by France’s official annual art show, the Salon. At first, people were surprised by the roughness of their brushmarks and thought their paintings looked like sketches. The name “Impressionism” was supposed to be an insult, with one reviewer of their first show saying that wallpaper looked more finished than Monet’s painting Impression Sunrise (1872, Musée Marmottan Monet).

The Impressionists were not interested in painting stories from history on a grand scale, which was the traditional route to achieving artistic success. Instead, they chose to paint scenes of everyday life. They captured the modern spaces of the city, such as cafes and theatres. For the female Impressionists, like Berthe Morisot, it was friends and family at home or in the garden. The group are also associated with landscape paintings, which they made directly from nature at a time when most of the works exhibited at the Salon were still produced in the studio. They would capture the sensations of a particular place and time of day with taches (marks) of colour.

You could try the senses palette and poem activities with the following works:

Claude Monet, Autumn Effect at Argenteuil, 1873

Pierre Auguste Renoir, La Loge (Theatre Box), 1874