2025

Abstract Erotic: Louise Bourgeois, Eva Hesse, Alice Adams

20 Jun – 14 Sep 2025

In summer 2025, visitors experienced extraordinary sculptures by Louise Bourgeois, Eva Hesse and Alice Adams at The Courtauld Gallery. Three pioneering artists of the 20th century who, in 1960s New York, produced startling new bodies of work turning modern sculpture on its head.

The major exhibition foregrounded their shared commitment to using humour and abstract form to ask important questions about sexuality and bodies.

The Griffin Catalyst Exhibition: Goya to Impressionism

14 Feb – 26 May 2025

In 2025, The Courtauld Gallery presented an exceptional selection of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings in the first ever exhibition of the Oskar Reinhart Collection ‘Am Römerholz’ to be staged outside of Winterthur, Switzerland. The exhibition was a unique opportunity to see some of its masterpieces – including works by Goya, Monet, Renoir, Van Gogh, Picasso,and Cezanne among others.

2024

The Griffin Catalyst Exhibition: Monet and London. Views of the Thames

27 Sept 2024 – 19 Jan 2025

Some of Monet’s most remarkable Impressionist paintings were made not in France but in London. They depicted extraordinary views of the Thames as it had never been seen before, full of evocative atmosphere, mysterious light and radiant colour. This exhibition realised Monet’s unfulfilled ambition of showing his extraordinary Thames group of paintings in London, and just 300 metres from the Savoy Hotel where many of them were painted. By presenting the paintings Monet himself selected for his public in Paris and London, it provided visitors with the unique experience of seeing the show Monet curated and the works he felt best represented his ambitious artistic enterprise — brought together for the first time 120 years after their inaugural exhibition.

Roger Mayne: Youth

14 Jun – 1 Sept 2024

Acclaimed British photographer Roger Mayne (1929–2014) was famous for his evocative documentary images of young people growing-up in Britain in the mid-1950s and ‘60s.

This exhibition, of around 60 almost exclusively vintage photographs, includes many of his iconic street images of children and teenagers, alongside an almost entirely unknown selection of intimate and moving later images of his own family at home in Dorset, as well as those taken on his honeymoon in Spain in 1962.

The Griffin Catalyst Exhibition: Frank Auerbach. The Charcoal Heads

9 Feb – 27 May 2024

This exhibition was the first time Frank Auerbach’s extraordinary post-war drawings, made in the 1950s and early 1960s, have been brought together as a comprehensive group. They were shown together with a selection of paintings he made of the same sitters; for him, painting and drawing have always been deeply entwined. The exhibition was a unique opportunity to see early masterpieces by one of the world’s most celebrated living artists.

2023

Claudette Johnson: Presence

29 Sept 2023 – 14 Jan 2024

Presenting a carefully selected group of major works from across her career, from key early drawings such as the arresting I Came to Dance, 1982, and And I Have My Own Business in This Skin, 1982, alongside recent and new works, this exhibition offers a compelling overview of Johnson’s pioneering career and artistic development.

The Morgan Stanley Exhibition: Peter Doig

10 Feb – 29 May 2023

A major exhibition of new and recent works by Peter Doig – including paintings created since the artist’s move from Trinidad to London in 2021. The Morgan Stanley Exhibition: Peter Doig presents an exciting new chapter in the career of one of the most celebrated and important painters working today. It is the first exhibition by a contemporary artist to take place at The Courtauld since it reopened in November 2021 following its acclaimed redevelopment.

2022

Fuseli and the Modern Woman: Fashion, Fantasy, Fetishism

14 Oct 2022 – 8 Jan 2023

This exhibition focuses on Henri Fuseli’s numerous private drawings of the modern woman. Blending observed realities with elements of fantasy, these studies present one of the finest draughtsmen of the Romantic period at his most original and provocative. Organised in collaboration with the Kunsthaus Zürich, the exhibition showcased drawings brought together from international collections

Edvard Munch. Masterpieces from Bergen

27 May – 4 Sept 2022

A major collection of works by Edvard Munch shown in the UK for the first time at The Courtauld Gallery. The exhibition was part of a partnership between The Courtauld and KODE Art Museums in Bergen, Norway.

Read

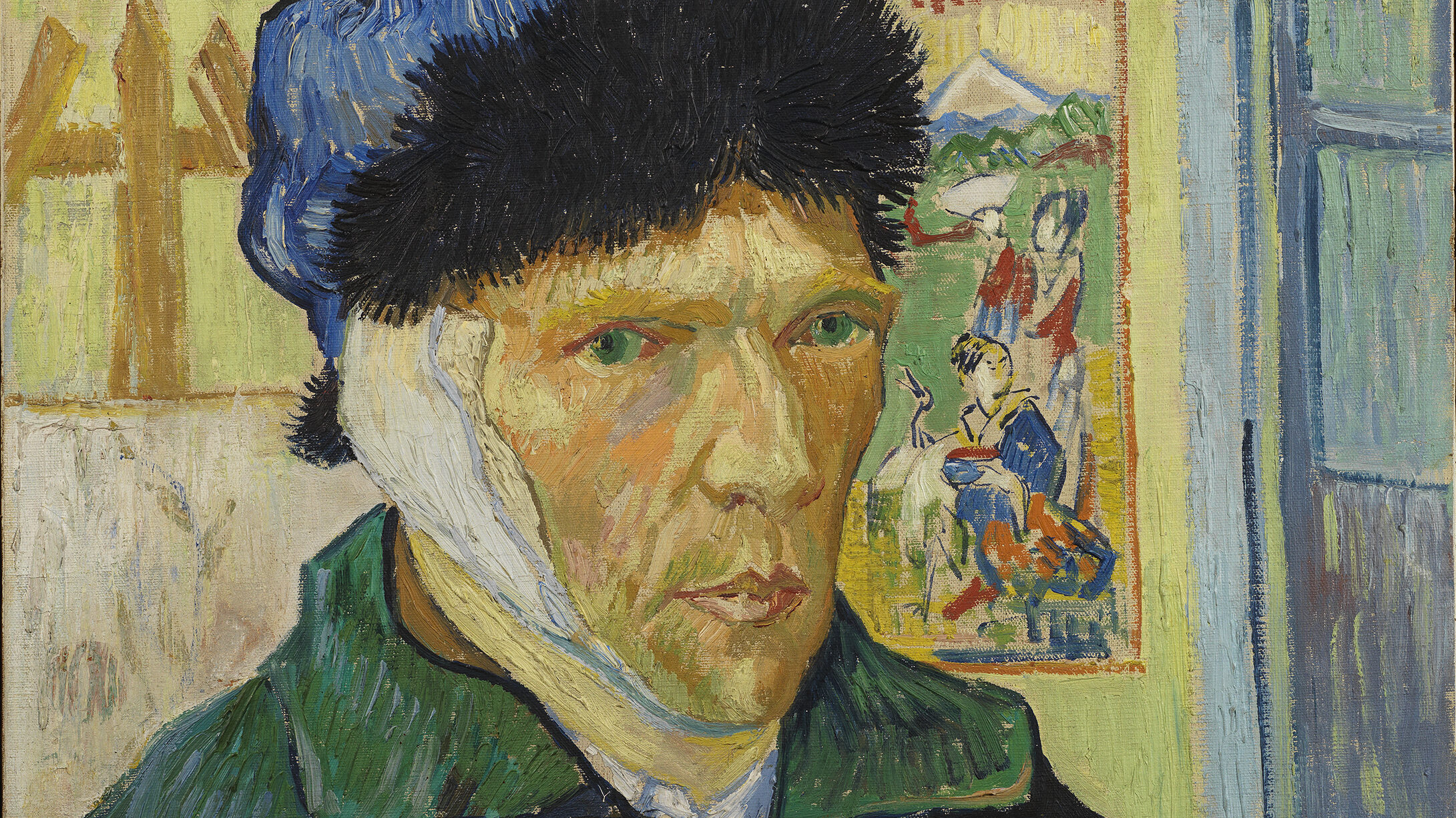

Van Gogh. Self-Portraits

3 Feb – 8 May 2022

The first ever exhibition devoted to Vincent van Gogh’s self-portraits across his entire career. An outstanding selection of 16 self-portraits have been brought together to trace the evolution of Van Gogh’s self representation

2021

Modern Drawings: The Karshan Gift

The opening display in the new temporary exhibition galleries showcased the gift of 24 important modern and post-war drawings presented by artist Linda Karshan in memory of her husband, Howard Karshan.

2017

Soutine’s Portraits: Cooks, Waiters & Bellboys

This exhibition brought together an outstanding group of portraits by Chaïm Soutine (1893-1943). Soutine was one of the leading painters in Paris in the 1920s and 1930s and was seen by many as the heir to Vincent van Gogh. This major exhibition was the first time he was ben exhibited in the UK in 35 years.

Bloomsbury Art & Design

The Courtauld holds one of the most extensive collections of works by artists from the Bloomsbury Group. This display presented a wide-ranging selection of objects from its holdings, many of which were bequeathed by the artist and art critic Roger Fry (1866 – 1934) to the newly formed Courtauld Institute of Art in 1935.

2016

Rodin and Dance: The Essence of Movement

This was the first major exhibition to explore Rodin’s fascination with dance and bodies in extreme acrobatic poses. It will explore a series of experimental sculptures known as the Dance Movements made in 1911, offering a rare glimpse into Rodin’s unique working practices.

Georgiana Houghton: Spirit drawings

Georgiana Houghton (1814-1884) was a Spiritualist medium who, in the 1860s and 70s, produced an astonishing series of abstract watercolours. Detailed explanations on the back of the works declare that her hand was guided by various spirits, including several Renaissance artists, as well as higher angelic beings. In this exhibition The Courtauld Galley explores this astounding series of largely abstract Victorian watercolours and offers visitors a unique opportunity to view remarkable works which have not been shown in the UK for nearly 150 years.

Botticelli and Treasures from the Hamilton Collection

This major exhibition featured no less than thirty of Botticelli’s exquisite drawings for Dante’s Divine Comedy alongside a selection of outstanding Renaissance illuminated manuscripts. These works were all sensationally sold to Berlin in 1882 by the 12th Duke of Hamilton. Dated to around 1480-95 and drawn on vellum, Botticelli’s Dante drawings are very rarely exhibited. This exhibition was an exceptional opportunity to see a representative collection of the great Renaissance master’s interpretation of one of the canonical texts of world literature. Ten drawings were included from each of the three parts of the Divine Comedy, charting Dante’s imaginary journey through Hell, Purgatory and Paradise.

Bruegel in Black & White: Three Grisailles Reunited

Despite his status as the most important Netherlandish painter of the sixteenth century, Pieter Bruegel the Elder (c.1525-1569) remains an elusive artist: fewer than forty paintings are attributed to him. This focused exhibition brought together for the first time Bruegel’s only three surviving grisaille paintings: The Courtauld’s Christ and the Woman Taken in Adultery, The Death of the Virgin from Upton House (National Trust) and Three Soldiers from the Frick Collection in New York.

2015

Soaring Flight: Peter Lanyon’s Gliding Paintings

This major exhibition explored a remarkable and unprecedented series of paintings by Peter Lanyon, one of Britain’s most important and original Post-War artists. Lanyon (1918-64) sought to create a new vision of landscape painting for the modern era that could express both sensory experience and a profound understanding of our fragile existence within the world. During the 1950s, he produced radical, near-abstract paintings of the tough coastal landscape of his native West Cornwall inspired by his experience of gliding, this series was showcased in a major retrospective at The Courtauld.

Bridget Riley: Learning from Seurat

In 1959 Bridget Riley painted a copy of Georges Seurat’s Bridge at Courbevoie, one of the highlights of The Courtauld Gallery. This experience represented a significant breakthrough for Riley, offering her a new understanding of colour and perception.

The lessons she took from Seurat emboldened her to strike out into the realm of pure abstraction and over the following few years she produced the first major abstract paintings based upon repeated geometric patterns for which she is today famed.

This seminal moment of artistic discovery is the springboard for a special display which will bring Seurat’s Bridge at Courbevoie with a selection of seven early works by Riley.

Unfinished… Works from The Courtauld Gallery

This Summer Showcase Special Display brought together paintings, sculpture drawings and prints from the Renaissance to the early twentieth century that have all been described – rightly or wrongly – as ‘unfinished’.

Many of the works on display were set aside by a dissatisfied artist or left incomplete upon their death, providing a fascinating insight into the interrupted artistic process.

Goya: The Witches and Old Women Album

This major exhibition reunited all the surviving drawings from the Witches and Old Women Album for the first time, offering a fascinating and enlightening view of a very private and personal Goya.

Drawn in the last decade of his life, the album was never meant to be seen beyond a small circle of friends. Goya gave free rein to his creativity, inventing extraordinary images that range from the humorous to the sinister and the macabre.

In this exhibition visitors were invited to discover the private world of Goya’s boundless imagination, expressed through visions and nightmares, superstitions, and the problems of old age. Above all the drawings reveal Goya’s penetrating observation of human nature: our fears, weaknesses and desires.

2014

Egon Schiele: The Radical Nude

This exhibition brought together an outstanding group of the artist’s nudes to chart his ground-breaking approach during his short but urgent career.

Schiele’s technical virtuosity, highly original vision and unflinching depictions of the naked figure distinguish these works as being among his most significant contributions to the development of modern art.

This sharply-focused exhibition presented a major opportunity to see more than thirty of these radical works assembled from international public and private collections.

Jasper Johns: Regrets

The Courtauld Gallery displayed major new works by Jasper Johns, one of the world’s greatest living artists. Regrets was a haunting series of ten paintings and drawings inspired by an old photograph of Lucian Freud posing in Francis Bacon’s London studio.

Johns transformed the image by copying, mirroring and doubling it. Unexpectedly, the form of a skull emerged in his new composition, like an apparition.

Johns reworked the subject in a variety of media, creating works that can be experienced as a profound meditation on mortality, creativity and memory.

This exhibition was based upon one originally organised by The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Bruegel to Freud: Prints from The Courtauld Gallery

This special display offered an introduction to the largest but least known part of the Gallery’s outstanding collection – its holding of prints.

The Courtauld Gallery houses one of the most significant collections of works on paper in Britain, with approximately 7,000 drawings and watercolours and 20,000 prints ranging from the Renaissance to the 21st century.

This display of some thirty particularly remarkable and intriguing examples spans more than 500 years and encompasses a variety of printmaking techniques.

The selection included works by Mantegna, Bruegel, Canaletto, Picasso, Matisse and Freud.

Court and Craft: A Masterpiece from Northern Iraq

This exhibition told the story behind one of the most extraordinary objects in The Courtauld’s collection: a bag made in Northern Iraq around 1300.

No other object of this kind is known.

Inlaid with gold and silver and decorated with a courtly scene showing an enthroned couple as well as musicians, hunters and revellers, it ranks as one of the finest pieces of Islamic metalwork in existence.

A Dialogue with Nature: Romantic Landscapes from Britain and Germany

A Dialogue with Nature explored aspects of Romantic landscape drawing in Britain and Germany from its origins in the 1760s to its final flowering in the 1840s.

The exhibition brought together 26 major drawings, watercolours and oil sketches by artists including J.M.W. Turner, Samuel Palmer, Carl Philipp Fohr, and Caspar David Friedrich.

The exhibition was a collaboration between The Courtauld Gallery and The Morgan Library & Museum in New York and draws upon the complementary strengths of both collections.

2013

Richard Serra: Drawings for The Courtauld

Richard Serra: Drawings for The Courtauld presented twelve of Serra’s most recent drawings, created especially for this installation at The Courtauld Gallery.

Rising to prominence on the New York art scene more than forty years ago, Serra is now celebrated internationally, notably for his groundbreaking sculptures and for his radical approach to drawing.

The Young Dürer: Drawing the Figure

This exhibition brought together early figure drawings of the great German Renaissance artist Albrecht Dürer.

The Young Dürer concentrated on the artist’s journeyman years (c. 1490-96), during which he travelled widely and was exposed to a range of new influences.

The exhibition explored how Dürer reinvented artistic traditions through an ambitious new approach to the figure rooted in the study of his own body.

Antiquity Unleashed: Aby Warburg, Dürer and Mantegna

On 5 October 1905 an audience of some 300 people attended a lecture at Hamburg’s concert hall entitled ‘Dürer and Italian Antiquity’ (Dürer und die italienische Antike).

The speaker was Aby Warburg, who would go on to become one of the most influential art historians and cultural theorists of the 20th century.

Warburg illustrated his lecture with a striking display of ten original works of art borrowed for the occasion from the Hamburger Kunsthalle.

They included Albrecht Dürer’s early master drawing The Death of Orpheus, the celebrated engravings Melancholia I and Nemesis, and four exceptional prints by Andrea Mantegna (c.1431-1506).

Featuring the very same works of art, this exhibition recreated Warburg’s seminal display to consider his influential contribution to the study of Albrecht Dürer.

Collecting Gauguin: Samuel Courtauld in the ’20s

Collecting Gauguin offered a fascinating insight into the development of Gauguin’s reputation in the UK.

The Courtauld Gallery holds the UK’s most important collection of works by the Post-Impressionist master Paul Gauguin. Assembled by the pioneering collector Samuel Courtauld, it includes five major paintings, ten prints, as well as one of only two marble sculptures ever created by the artist.

Becoming Picasso: Paris 1901

Becoming Picasso: Paris 1901 reunited major paintings from his debut exhibition with the influential dealer Ambroise Vollard.

These works show the young painter taking on and transforming the styles and subjects of major modern artists of the age, such as Van Gogh, Degas and Toulouse-Lautrec.

This exhibition brings together a spectacular group of these paintings, offering a unique opportunity to experience the birth of Picasso’s genius.

2012

Peter Lely: A Lyrical Vision

Peter Lely was England’s leading painter from the period of the Civil War to the reign of Charles II.

Known principally for his portraits of court beauties, Lely devoted his early career to ambitious paintings of figures in idyllic landscapes.

This exhibition was the first to examine this remarkable but forgotten group of early paintings.

Mantegna to Matisse: Master Drawings from The Courtauld Gallery

Spanning over 500 years, this exhibition included rarely seen drawings by Dürer, Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo as well as masterpieces by Rembrandt, Cézanne, Van Gogh and Matisse.

This exhibition celebrated the art of drawing and offers a unique opportunity to enjoy some of the very greatest works from the Courtauld’s collection.

Mondrian || Nicholson: In Parallel

This exhibition explored the largely untold relationship between Piet Mondrian and Ben Nicholson during the 1930s. At this time the two artists were leading forces of abstract art in Europe.

Their friendship culminated with Mondrian moving to London in 1938, at Nicholson’s invitation, where the two worked in neighbouring Hampstead studios at the centre of an international community of avant-garde artists.

This was a unique opportunity to experience some of the greatest works ever produced by these two exceptional artists.

2011

The Spanish Line: Drawings from Ribera to Picasso

This exhibition explored the rich, intriguing and varied territory of Spanish drawings, a field that remains relatively little known.

The Courtauld Gallery holds one of the most important collections of Spanish drawings outside Spain, totalling approximately 100 works ranging from the 16th to the 20th centuries. A selection of some 40 of the finest and most representative drawings were chosen for the exhibition.

Toulouse-Lautrec and Jane Avril: Beyond The Moulin Rouge

Jane Avril, the dancer, was one of the stars of the Moulin Rouge in the 1890s. Known for her alluring style and exotic persona, her fame was assured by a series of dazzlingly inventive posters designed by the artist Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Jane Avril became an emblematic figure in Lautrec’s world of dancers, cabaret singers, musicians and prostitutes. She was also a close friend of the artist and he painted a series of striking portraits of her. These go beyond Toulouse-Lautrec’s exuberant poster images of the start performer and give a more private account of Avril captured off-stage.

This landmark exhibition was the first to celebrate this remarkable creative partnership which has to come to define the world of the Moulin Rouge. Bringing together Toulouse-Lautrec’s most famous paintings, posters and prints from international collections, it captured the excitement and spectacle of bohemian Paris in the 1890s.

Life, Legend, Landscape: Victorian Drawings and Watercolours

This exhibition presented a rich selection of Victorian drawings and watercolours from The Courtauld Gallery’s world-famous collection. Many of these works are shown for the first time. They range from exquisite highly finished watercolours to informal sketches and preparatory drawings for paintings and sculpture.

2010

Cézanne’s Card Players

Paul Cézanne’s famous paintings of peasant card players have long been considered to be among his most iconic and powerful works. This landmark exhibition was the first to bring together the majority of these remarkable paintings alongside a magnificent group of closely related portraits of Provençal peasants and rarely seen preparatory oil sketches, watercolours and exquisite drawings.

The Courtauld Collects! 20 Years of Acquisitions

This display explored some of the exceptional new additions to The Courtauld’s collection twenty years after its move to Somerset House. Highlights included works ranging from Turner, Degas and Seurat to Anish Kapoor and Damien Hirst. The show also unveils one of the most important new acquisitions, Joshua Reynolds’s late masterpiece Cupid and Psyche.

The Courtauld Gallery is sometimes described as a “collection of collections” and has grown historically through the generosity of private individuals who have endowed it with the remarkable collections which they formed.

Michelangelo’s Dream

Michelangelo’s masterpiece The Dream is one of the greatest of all Renaissance drawings. This complex work shows a nude youth being roused by a winged spirit from the vices that surround him.

The Dream was probably part of the celebrated group of drawings which Michelangelo made as gifts for Tommaso de’ Cavalieri, a young Roman nobleman with whom he had fallen passionately in love. With loans from international collections, the exhibition united The Dream for the first time with these extraordinary drawings.

2009

Frank Auerbach: London Building Sites 1952–62

This was the first exhibition to explore the extraordinary group of paintings of post-war London building sites by Frank Auerbach (born 1931), one of Britain’s greatest living artists.

Fascinated by the rebuilding of London after the Second World War, Auerbach combed the city’s numerous building sites with his sketchbook in hand. Back in his studio he worked and reworked each painting over many months resulting in thickly built up paint surfaces more than an inch.

The exhibition reunited the complete series of building site paintings together with rarely seen oil sketches and a number of recently rediscovered sketchbook drawings. These works are among the most important contributions to post-war painting in Britain, produced at a time when Auerbach emerged alongside Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud as part of a powerful new generation of British painters.

Beyond Bloomsbury: Designs of The Omega Workshops 1913–19

Established in 1913 by the painter and influential art critic Roger Fry, the Omega Workshops were an experimental design collective, whose members included Vanessa Bell, Duncan Grant and other artists of the Bloomsbury Group.

The exhibition united The Courtauld’s uniquely important collection of Omega working drawings with the finest examples of the Workshops’ printed fabrics, Cubist-inspired rugs and splendidly painted textiles, as well as ceramics and furniture to explore the Omega Workshops’ radical approach to modern design.

Love and Marriage in Renaissance Florence: The Courtauld Wedding Chests

This exhibition was the first in the UK to explore this important and neglected art form of Renaissance Florence. The exhibition was focused around two of The Courtauld’s great treasures: the pair of chests ordered in 1472 by the Florentine Lorenzo Morelli to celebrate his marriage with Vaggia Nerli. These are the only pair of cassoni to be still displayed with their painted backboards (spalliere).The unusual survival of both the chests and their commissioning documents enables a full examination of this remarkable commission.

The Courtauld cassoni were displayed alongside other superb examples of chests and panels. Discover the stories behind these chests and gain rich insights into Florentine art and life at the height of the city’s glory.

2008

Paths to Fame: Turner Watercolours from The Courtauld

This exhibition was the first full display of The Courtauld Gallery’s outstanding collection of watercolours by J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851). The works span the artist’s career from important early landscapes made when he was a teenager, to the highly finished watercolours and his celebrated expressive late works.

The works from The Courtauld Gallery were supplemented by closely related loans from Tate and private collections, enabling viewers to see the development of some compositions from early sketches and exploratory ‘colour beginnings’ to finished watercolours and published prints.

The Courtauld Cézannes

The Courtauld Gallery holds the most important group of works by Paul Cézanne (1839-1906) in Britain. This exhibition presented the entire collection for the first time with major paintings such as the iconic Montagne Sainte-Victoire (1887) and Card Players (1892-5) shown alongside rarely seen drawings and watercolours.

Also on display was a previously unexhibited group of nine autograph letters in which Cézanne reflects upon the principles of his artistic practice.

Renoir at the Theatre: Looking at La Loge

Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s La Loge (The Theatre Box), 1874, is a masterpiece of Impressionist painting and one of the most famous works in The Courtauld Gallery’s collection. The exhibition united this exceptional picture with Renoir’s other paintings of elegant Parisians on display in their loges.

It also included other depictions of the theatre box by his Impressionist contemporaries, with important works by Mary Cassatt, Edgar Degas and others borrowed from international collections. Their shared interest in the spectacle of modern society at the theatre is further explored through a rich array of printed material such as contemporary fashion magazines and caricatures.

2007

Walter Sickert: The Camden Town Nudes

25 October 2007 – 20 January 2008

At the beginning of the 20th century, Walter Sickert (1860-1942) painted a remarkable series of female nudes which confirmed his reputation as one of the most important modern British artists.

This was the first exhibition devoted to these radical works produced in Camden Town, north London, between 1905 and 1913. The uncompromising realism of Sickert’s nudes, set on iron bedsteads in the murky interiors of cheap lodging houses, challenged artistic conventions and divided critical opinion.

Temptation in Eden: Lucas Cranach’s Adam and Eve

This stunning exhibition was the first in Britain devoted to the great German Renaissance painter Lucas Cranach the Elder (c.1472-1553).

Temptation in Eden focused on one of Cranach’s most memorable and enchanting works: the Courtauld’s Adam and Eve, painted in 1526 when the artist was at the height of his powers. This beguiling painting demonstrates Cranach’s outstanding gifts as a portrayer of landscape, animals and the female nude.

Guercino: Mind to Paper

Giovanni Francesco Barbieri (1591-1666), nicknamed Guercino (“squinter”) after a childhood incident left him cross-eyed, is regarded as one of the most significant Italian artists of the Baroque period. A prolific and fluent draughtsman who was known as ‘the Rembrandt of the South’, he was hailed for his inventive approach to subject matter, his deftness of touch and his ability to capture drama and movement. This exhibition reflected the artist’s extraordinary technical and stylistic versatility, and was the second joint exhibition to be organised as part of the Courtauld Institute of Art’s ongoing collaboration with the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

2006

David Teniers and the Theatre of Painting

19 October 2006 – 21 January 2007

This exhibition told the story of one of the most remarkable artistic enterprises of the 17th century: David Teniers’ publication in 1660 of the Theatrum Pictorium or ‘Theatre of Painting’, the first illustrated printed catalogue of a major paintings collection. With loans from the Museo del Prado, the Royal Collection, the National Gallery of Ireland, Glasgow Museums and the British Library, the exhibition gave an in-depth account of this influential project which provided the foundations for the modern catalogue and documented one of the greatest princely collections ever assembled.

All Spirit and Fire: Oil Sketches by Tiepolo

Venetian painter Giovanni Battista Tiepolo (1696-1770) was one of the greatest and most imaginative artists of 18th century Europe. He is best known for his monumental frescoes and altarpieces. Yet some of Tiepolo’s finest work can be found in the small, rapidly executed oil sketches which he made in association with these grand compositions. They exemplify the qualities of all spirit and fire which contemporaries saw as characteristic of Tiepolo’s work.

This exhibition was focused around the important group of oil sketches and drawings by Tiepolo belonging to The Courtauld and other British collections, spanning his entire working life. The unusual intimacy of these confident and fluid works of art reveal the vigorous imagination of a great artist at work.

2005

André Derain: The London Paintings

27 October 2005 – 22 January 2006

André Derain (1880-1954) came to London in 1906 to paint a series of works that would rival Claude Monet’s earlier celebrated views of the city. The result was an extraordinary group of large-scale paintings which overthrew conventions with their unrestrained use of pure colour and exuberant brushwork. This was the first exhibition dedicated to these masterpieces of 20th century art and showed 12 of the most important works from galleries around the world together in one room.

Gabriele Münter: The Search for Expression 1906-1917

Gabriele Münter (1877-1962) played a vital role in the development of German Expressionism in the early years of the 20th century. She was at the forefront of a group of highly influential avant-garde artists, including her lover Wassily Kandinsky, who redirected the course of German modernism and shaped Expressionist aesthetics.

This exhibition charted Münter’s extraordinary artistic development from her early Impressionist-inspired paintings of Sèvres on the outskirts of Paris, to the bold and brightly coloured innovative Expressionist works she produced in the small town of Murnau, deep in the Bavarian Alps.

Drawings Gallery exhibitions and displays

2025

Louise Bourgeois: Drawings from the 1960s

20 Jun – 17 Sep 2025

To coincide with the exhibition Abstract Erotic: Louise Bourgeois, Eva Hesse, Alice Adams, this focused display presented a group of drawings by Bourgeois from the 1960s, mostly on loan from The Easton Foundation of New York. These dreamlike works illustrate the central role of drawing in her work and the way it intertwined with her sculptural practice during those years.

Henri Michaux: The Mescaline Drawings

12 Feb – 4 Jun 2025

This display celebrated the unique Mescaline Drawings by the Franco-Belgian poet and visual artist, Henri Michaux (1899-1984). Presenting works rarely seen in the UK, the display showcased Michaux’s extraordinary experience, one that pushed the limits of what the essence of drawing is.

2024

Drawn to Blue: Artists’ use of blue paper

4 Oct 2024 – 26 Jan 2025

This display presented a selection of drawings on blue paper from The Courtauld’s collection, ranging from works by the Venetian Renaissance artist Jacopo Tintoretto to a watercolour by famed English Artist Joseph Mallord William Turner.

Henry Moore: Shadows on the Wall

Shadows on the Wall investigated the artist’s fascination with the curved brick walls and cavernous tunnels of those spaces, taking these drawings as a point of departure for interpreting some of his post-war drawings and sculpture.

Presented in collaboration with the Henry Moore Foundation.

The exhibition was made possible as a result of the Government Indemnity Scheme.

From the Baroque to Today: New Acquisitions of Works on Paper

This display presented a selection of drawings and prints acquired by The Courtauld since 2018. Highlights include a 17th-century Florentine drawing which was reunited for the first time with its left half from which it was cut at some point in its history.

Female artists are significantly represented, the selection includes works by Mary Cassatt (the first by the Impressionist painter to enter the collection), Maliheh Afnan, Deanna Petherbridge and Susan Schwalb.

2023

La Serenissima: Drawing in 18th century Venice

This display presented an outstanding group of around twenty Venetian drawings from The Courtauld’s collection. They evoke the energy and creativity of Venice at a time when the city flourished as one of the great cultural capitals of Europe.

Art and Artifice: Fakes from the Collection

This display showcased drawings, paintings, sculpture and decorative arts that are not what they seem. It presented remarkable forgeries from The Courtauld’s collection and told the stories behind their making and the discovery of their deception.

Peter Doig: Etchings for Derek Walcott

This exhibition presents for for the first time a series of 19 etchings by Peter Doig (born 1959) inspired by the work of his friend, the poet Derek Walcott (1930 – 2017).

The Morgan Stanley Exhibition: Peter Doig was also on display in the Denise Coates Exhibitions Gallery.

2022

Helen Saunders: Modernist Rebel

Helen Saunders: Modernist Rebel showcases a remarkable group of 18 of the artist’s drawings and watercolours, given to The Courtauld in 2016 to form the largest public collection of Saunders’s work in the world. This monographic exhibition at The Courtauld was the first devoted to her work in over 25 years.

Traces: Renaissance Drawings for Flemish Prints

Showcasing a selection from The Courtauld’s rich collection of works on paper, this display explored the world of 16th century Flemish print production. It featured print designs by some of the greatest Netherlandish artists of the era, including Pieter Bruegel the Elder (ca. 1525–1569) and Maerten van Heemskerck (1498–1574).

The Art of Experiment: Parmigianino at The Courtauld

This display presented an important group of twenty-two works by Parmigianino from The Courtauld’s collection. They include a sketch for the artist’s most ambitious painting, the Madonna of the Long Neck.

2021

Pen to Brush: British Drawings and Watercolours

Pen to Brush, the opening display in the dedicated Gilbert and Ildiko Butler Drawings Gallery, featured highlights from The Courtauld’s remarkable collection of British drawings and watercolours.

They range from one of the earliest and smallest works in the collection, a pen and ink drawing by Isaac Oliver measuring just 47 x 59 mm (around 1565-1617), to Henry Moore’s powerful wartime Shelter Drawing (1942).

2018

Artists at Work

Artists have long taken pleasure in representing themselves at work, in their studios or academies, out and about in a landscape or recording their own likeness. Immersed in nature, artists are often shown almost lost in the geographical vastness they are recording. Depictions of the artist in the studio are about creative concentration and introspection and, like self-portraits, are reflections on practice and identity. The care taken in recording the studio apparatus of easels, palettes, or assistants grinding pigments, indicates their significance for practitioners. The studio might be the everyday workshop of dirty brushes and sculptural debris, but it is also the place of allegory and myth where artists perform or dream. Through a selection of drawings from the sixteenth to the twentieth century, this exhibition aims to illustrate the range in which artists have represented themselves and others making art.

This exhibition was curated by Deanna Petherbridge, author of The Primacy of Drawing: Histories and Theories of Practice, in collaboration with Anita Viola Sganzerla, and was accompanied by a catalogue written by these two authors.

Antoine Caron: Drawing for Catherine de’ Medici

This focused international loan exhibition, the first dedicated to the drawings of Antoine Caron (1521-1599), brought together a celebrated group of drawings executed for his patron Catherine de’ Medici, queen of France (1519-1589). Centred around the Valois series, a set of drawings of courtly pageantry here reunited for the first time, the display showcased the way in which the powerful and influential Catherine promoted herself and her dynasty through a series of lavish courtly events.

2017

Drawing Together

30 September 2017 – 2 January 2018

The act of drawing is a journey of discovery. Whether the artist is working from a model, memory or the imagination, the process of drawing offers a series of encounters between what is sought and what surprises along the way. The sheet of paper becomes the record of these encounters, capturing a moment in time. For viewers, the immediacy of drawing thus provides a greater intimacy with its creator. It also provides contemporary artists with an invaluable glimpse into the mind of their predecessors.

Drawing Together sought to stimulate new insights by presenting unexpected pairings of drawings from The Courtauld Gallery’s collection and by living artists. These pairings reveal inevitable contrasts, but also highlight underlying similarities in the exploratory processes of artists across centuries. The timeless quality of drawing allows for stimulating comparisons that transcend function and period.

William Henry Hunt: Country People

This focused display of 20 drawings and watercolours was the first exhibition to investigate William Henry Hunt’s depiction of rural figures in his work of the 1820s and 1830s. It took its lead from a watercolour in The Courtauld Gallery’s permanent collection, The Head Gardener, which was shown alongside significant loans from institutions and private collections.

Reading Drawings

Inscriptions on drawings reveal essential information about their authorship, dating, subject matter, purpose and history. In Reading Drawings, a selection of works from The Courtauld Gallery’s own collection demonstrated the varying reasons both artists and collectors wrote on drawings, ranging from straightforward signatures to lengthy captions, invented languages and marks of ownership.

2016

A Civic Utopia: Architecture and the City in France, 1765-1837

8 October 2016 – 8 January 2017

This exhibition considered the place of architecture in establishing the notion of public life. It brings together an outstanding selection of architectural drawings of public building and public space in France that pursued the Enlightenment idea of a ‘scientific’ city, expressing rational, hygienic and symbolic expressions of an ideal civic life.

Focusing on the spaces of everyday life rather than grand and largely unbuilt urban schemes, the display featured drawings for a wide range of new public buildings and settings, including city markets, exchange halls, prisons, parks, abattoirs, hospitals and cemeteries.

This exhibition was organised by Drawing Matter Trust in collaboration with The Courtauld Gallery as part of UTOPIA 2016: A Year of Imagination and Possibility, Somerset House’s celebration of the 500th anniversary of Thomas More’s Utopia. It was curated by Nicholas Olsberg and Basile Baudez.

Regarding Trees

This display of drawings, drawn from The Courtauld Gallery’s collection, explored artists’ enduring fascination with the tree. Ranging from the early sixteenth to the mid nineteenth centuries and including works by Fra Bartolommeo, Jan van Goyen, Claude Lorrain and John Constable, among others, it takes the framework of Gilpin’s treatise as its starting point, moving from portraits of individual trees to depictions of trees within landscapes and concluding with a selection of forest scenes. Together, they offer an insight into some of the many roles trees have played over the centuries.

Ornament By Design

Ornament by Design examined the interplay between ornament and architecture in drawing. It traced the manifold ways in which the subtle, seductive lines of ornament can transform the surface of buildings and things into objects of desire. The display presented a range of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century French drawings: architectural elevations and sections, designs for ceilings and garden ornaments, capriccios and studies for specific motifs such ornamental brackets and frames.

Bruegel, Not Bruegel

The Netherlandish artist Pieter Bruegel the Elder (around 1525–1569) achieved widespread fame for his innovative graphic works. Bruegel’s close observation and exceptional skills as a draughtsman result in a palpable vision of the natural world in his landscapes, whilst his figural compositions burst with rich and keenly observed detail.

The numerous works produced in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries that closely imitate his style attest to Bruegel’s lasting visual influence and, more practically, catered to continued demand amongst collectors. This display brought together works by Bruegel and works formerly attributed to him within The Courtauld Gallery’s collection to examine this legacy.

2015

Panorama

26 September 2015 – 10 January 2016

This display, which ran concurrently with the exhibition Soaring Flight: Peter Lanyon’s Gliding Paintings, explored the tradition of panoramic landscape before the age of powered flight. Ranging from the sixteenth through the nineteenth centuries and including works by John ‘Warwick’ Smith, J. M. W. Turner, Canaletto and Adam Frans van der Meulen, it considered some of the many facets of artists’ enduring fascination with the infinite.

Jonathan Richardson By Himself

Jonathan Richardson the Elder (1667 – 1745) was one of the most influential figures in the visual arts of 18th century England. A leading portrait painter, Richardson was also a theorist and an accomplished poet and amassed one of the great collections of drawings of the age.

Towards the end of his life Richardson created a remarkable but little known series of self-portrait drawings. They show Richardson adopting a wide range of poses, guises and dress, in some cases deliberately evoking other artists, such as Rembrandt, whose work he owned.

These remarkable drawings show Richardson considering and making visual the different aspects of himself. But much more than this, they were the means with which he reviewed his life and achievements.

Renaissance Modern

Renaissance Modern, conceived and organised by students from The Courtauld and the University of Manchester in collaboration with their tutors and with Stephanie Buck, the Martin Halusa Curator of Drawings at The Courtauld Gallery, examined how artists working in a variety of media sought to challenge established ideas about art and creativity during the sixteenth century. It focused on drawings produced in Italy, primarily Florence and Rome, but also includes examples from Northern Europe, many of which have never been studied before.

Unseen

The first in a series of revelatory displays at The Gilbert and Ildiko Butler Drawings Gallery highlighted the range and depth of the collection with examples of some of its most intriguing works.

Unseen focuses on works, which have not been exhibited at The Courtauld in the last 20 years, often by fascinating lesser-known artists.

The selection of works ranged across the centuries from the Renaissance to the birth of Pop Art, with pieces as diverse as Two men in conversation, a striking 15th century Renaissance drawing from the school of Francesco Squarcione, to Africa, a work from 1962 by Larry Rivers, the godfather of Pop Art.

Project Space displays

2025

Post-War Abstraction: Works from the Courtauld

2 Jul – 12 Oct 2025

Drawn from the Courtauld’s significant collection of post-war art, this Project Space display examined forms of abstraction which emerged in Europe and America in the 1950s and 1960s.

It explored the radical approaches towards non-representational image making and experimentation with techniques and materials that characterised the work of artists including Philip Guston, Jean Dubuffet, and Joseph Beuys. Many of these works were recent additions to The Courtauld’s collection as gifts and promised gifts from the Karshan collection.

With Graphic Intent

1 Mar – 22 Jun 2025

This focused display showcases highlights from The Courtauld’s collection of German and Austrian modernist works on paper – including pencil and ink drawings, lithographs, woodblock prints and etchings – by some of the best-known artists from the period such as Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee and Oskar Kokoschka.

2024

Medieval Multiplied: A Gothic Ivory and its Reproductions

This display draws from the collections of The Courtauld and V&A to explore how different technologies of reproduction have shaped encounters with artworks since the 19th century.

Juxtaposing a spectacular Gothic ivory carving with multiple reproductions of it – from engravings, photographs and plaster casts to 3D prints and digital models – the display offers unparalleled opportunities to compare these technologies side-by-side.

Vanessa Bell: A Pioneer of Modern Art

25 May – 6 Oct 2024

This focused display was the first devoted to The Courtauld’s significant collection of Bell’s work. It included her masterpiece A Conversation, as well as the bold, abstract textile designs she produced for the Omega Workshops, led by influential artist and critic Roger Fry in London, which aimed to abolish the boundaries between the fine and decorative arts and bring the arts into everyday life.

Jasper Johns: The Seasons

Between 1984 and 1991, the pioneering American artist Jasper Johns (b.1930), focused on the theme of the four seasons and produced an ambitious and extensive series of prints, full of rich and complex imagery.

This display featured a series of prints given to The Courtauld in 2016 by Barbara Bertozzi Castelli, the widow of John’s long-term dealer Leo Castelli, and is the only museum in the United Kingdom to have such a comprehensive group of these prints in its collection.

2023

Reworking Manet

This exhibition showcased a selection of outstanding works made by students aged 14–18 from across the UK. They were creative responses to Édouard Manet’s famous painting A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (1882) in The Courtauld collection.

Art and Artifice: Fakes from the Collection

This display showcased drawings, paintings, sculpture and decorative arts that are not what they seem. It presented remarkable forgeries from The Courtauld’s collection and told the stories behind their making and the discovery of their deception.

Drawing on Arabian Nights

This display presents thirteen Orientalist works from The Courtauld’s Drawings collection, including works by Édouard Manet, John Frederick Lewis and the British-Syrian translator and poet Yasmine Seale. Several of these striking works are being displayed for the first time.

2022

A Modern Masterpiece Uncovered: Wyndham Lewis, Helen Saunders and Praxitella

This display in The Courtauld’s Project Space presented an important lost masterpiece by one of the early 20th century’s most radical female abstract artists, Helen Saunders (1885-1963).

In 2019, two Courtauld students, Rebecca Chipkin and Helen Kohn, were researching Wyndham Lewis’s (1882-1957) major modernist portrait Praxitella (1921), on loan from Leeds Art Gallery, as part of a research project at The Courtauld’s Department of Conservation. During their six-month technical analysis of Praxitella, the students painstakingly analysed X-rays of the huge canvas, examining the painting’s chemical composition using high-resolution scanning equipment. It was only after they spotted a reproduced image of Atlantic City (c.1915) in Blast, the avant-garde journal of the Vorticist movement, that the students identified the artwork beneath Wyndham Lewis’ painting as one by his friend and colleague Helen Saunders.

This display presented Praxitella alongside the x-ray and partial colour reconstruction of Atlantic City, as well as a range of technical material to tell the story of this extraordinary discovery.

2021

Courtauld Connections: Works from our National Partners

23 Jun – 2 Oct 2022

Since 2018, The Courtauld has partnered with a range of UK museums and galleries on a collaborative programme of 11 loan-based exhibitions and public engagement activities, inspired by the art collection of its founder Samuel Courtauld and the history of his chairmanship of textile company Courtaulds Ltd.

Courtauld Connections: Works from our National Partners celebrated these partnerships with a specially curated display of five paintings and drawings by major British artists of the 20th century

Kurdistan in the 1940s

20th Century British photographer Anthony Kersting, the most prolific and widely travelled architectural photographer of his generation, was the subject of the inaugural display in the new Project Space – a new gallery dedicated to spotlighting temporary projects that give visitors special insight into The Courtauld’s broader collection, conservation and research.

MA Curating the Art Museum Exhibitions

Unearthing: Memory, Land, Materiality

15 June – 3 Sept 2023

Zaha Hadid: Reimagining London

8 June – 2 July 2022

Both Sides of Here (digital exhibition)

Opened 16 June 2021

Unquiet Moments (digital exhibition)

June – July 2020

Generations: Connecting Across Time and Place

8 June – 3 July 2019

There Not There

14 June – 15 July 2018

CORPUS: The Body Unbound

16 June – 17 July 2017

Confusion of Tongues: Art and the Limits of Language

16 June – 17 July 2016

The Second Hand: Reworked Art Over Time

18 June – 19 July 2015

Impress: Print Making Expanded in Contemporary Art

20 June – 20 July 2014

Imagining Islands: Artists and Escape

20 June – 21 July 2013

Portrait of the Artist As…

26 June – 22 July 2012

Falling Up: The Gravity of Art

23 June – 4 Sept 2011

Blood Tears Faith Doubt: Historical and Contemporary Encounters

17 June – 18 July 2010

Once Upon a Time… Artists and Storytelling

25 June – 26 July 2009

Stages and Scenes: Creating Architectural Illusion

26 June – 27 July 2008

McQueens Illuminating Objects displays

Launched in 2012, the McQueens Illuminating Objects internship programme is supported by McQueens Flowers Ltd and explores some of the ornate, unusual and largely unknown objects in The Courtauld’s sculpture and decorative arts collections.

2023

A Cryptic Vessel

From July 2023

2022

The Bear in the Sandbox: Art Therapy and the Museum Object

August – December 2022

2021

A pair of gold beakers

From November 2021

Silk Fragment by Jock Turnbull in the Omega Workshops

May – September 2021

The Science Museum, London

2020

Habitation

2019

Painted ivory casket

7 June 2019 – early 2020

2017

17th Century Frame – Decorative Stones

8 June 2017- 15 Feb 2018

The Illuminating Objects internship programme is supported by McQueens Flowers Ltd