Gendered Readings of the Earliest Women’s Suffrage Iconoclasm

[This blog post was commissioned by The Courtauld’s Gender & Sexuality Research Group, published 7 October 2020]

Historically, museums and art galleries (hereafter ‘museums’) have largely been recognised as masculine venues governed and occupied by men and predominantly exploring male perspectives. Charles West Cope’s The Council of the Royal Academy Selecting Pictures for the Exhibition, 1875 (1876) readily shows the authority of male artists determining tastes in art for the British public. Depicting the multi-generational committee of celebrated Academicians such as President Sir Francis Grant and J.C. Horsley, alongside their younger counterparts John Everett Millais and Frederic Leighton, Cope exemplifies through the male gaze and its study of a young woman painted in pink with a child the patriarchal standards which dominated Victorian society and culture. In contrast to the active, scrutinising and authoritative representation of several male bodies, the female body is made singular, marginalised, barely visible, small and submissive. Her body is not only subjected to male representation both as a painting and in Cope’s replication, but it is also held on a canvas by two men for the committee to observe and scrutinise inside the gallery in the name of art. These gendered dynamics connect to cross-disciplinary studies in art history, museum studies, sociology, politics, literature, feminist cultural theory and female education, which examine the problematic institutional hierarchical binaries in society which favoured masculinity above femininity across centuries. For the Victorian era, these dynamics draw on and respond to debates focusing on the ‘Woman Question’ from the 1860s, the ‘New Woman’ from the 1890s, the formal education and training of women both at universities and in arts and crafts as advocated by John Ruskin and William Morris, and the campaign for women’s enfranchisement initiated during this period and extending into the early twentieth-century. Indeed, Cope’s painting carefully enacts these entrenched gendered social dynamics through his representation of the committee weighing the physical, economic and emotional worth of the painted female body against conventional standards of beauty. It is these men who determine whether the artistic embodiment of femininity before them has merit and is fit for display, observation, and study at the Royal Academy.

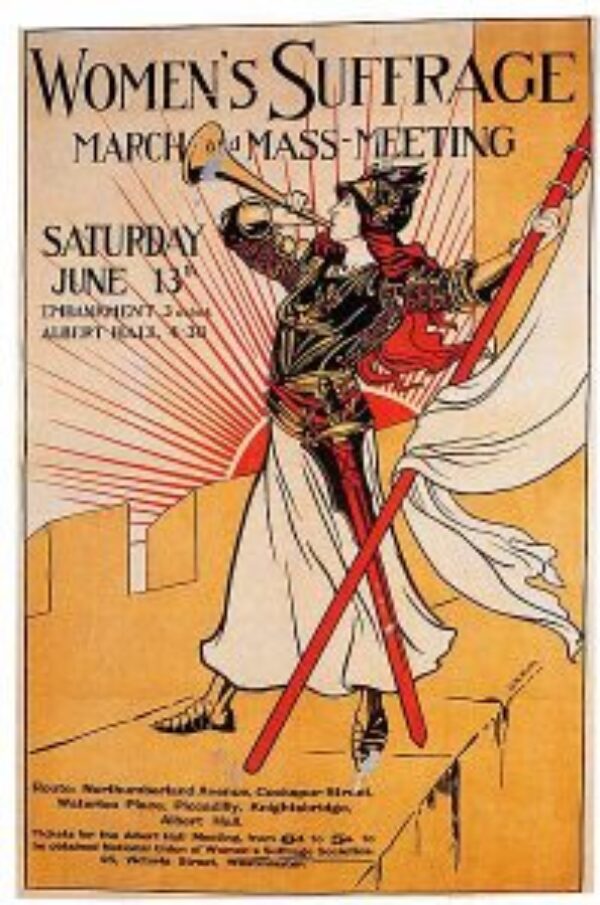

Although Cope may not have intended for his painting to serve as a catalyst for feminist readings of the museum space, it does unpack numerous debates about museum governance inherent in the protests against art carried out by the women’s suffrage movement in the name of women’s rights. Between 1913 and 1914, the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) launched a series of iconoclastic attacks which challenged government endorsement of museums in contrast to the value it placed on the women. After more than forty years of campaigning since the formation of the first British suffrage society, women had still not been granted the vote. Thousands faced daily economic and legal uncertainty. Members of the WSPU, as suffragettes, pursued militant or violent protest, in contrast to their sister suffragists who demonstrated peaceful and legally. For example, the Artist’s Suffrage League and the Suffrage Atelier provided visual iconography for the campaign at the same time as the WSPU developed tactics from window-smashing to the first orchestrated iconoclasm (Fig. 1).[1] The furore with which militants protested were exacerbated by suffragette experiences of increased police brutality, imprisonment and force-feeding.[2]

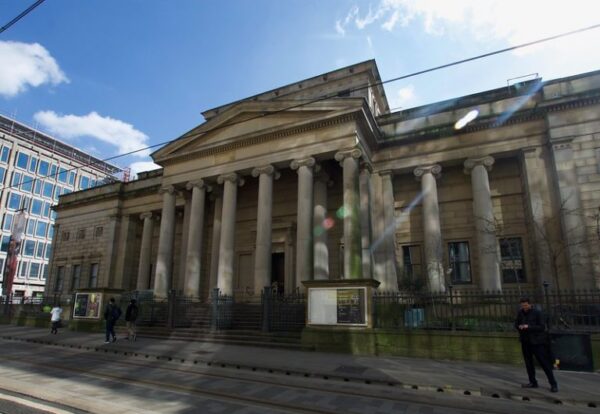

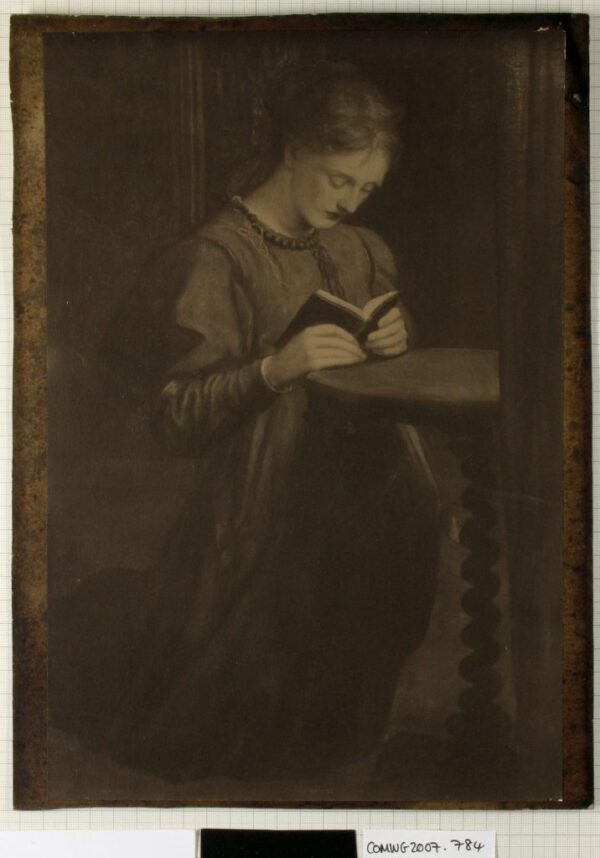

On 3rd April 1913, Evelyn Manesta, Lillian Forrester and Annie Briggs targeted thirteen of the most famous and important artworks at Manchester City Art Gallery (Fig. 2). Painted by many of the most prominent artists of the century, including George Frederic Watts, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais, Frederic Leighton and Edward Burne-Jones, these artworks were levelled for their national recognition, and local government patronage. May Prinsep title: Prayer (1860 hereon The Prayer, Fig. 3), Paolo and Francesca (1870, Fig. 4) and Portrait of The Honourable J L Motley (1861) by Watts, and Astarte Syriaca (1877) by Rossetti suffered the worst damages as their protective plate-glasses penetrated and fragmented paint and tore canvas. The total cost of damage was estimated at £170, the equivalent of £19,000 today.[3]One of the hammers used during the attack carried the colours of the WSPU and a card reading, ‘Parliament for dishonourable men: prison for honourable women’, ‘Stop forcible feeding’ and ‘Votes for Women’.[4]

This iconoclasm invites us to consider gendered readings of the museum space in reference to women’s rights and the display of Victorian art (Fig. 5). Scholarship widely accredits Mary Richardson’s attack against Diego Velázquez’s The Toilet of Venus, also more commonly known as The Rokeby Venus, for utilising a new and radical tactic in WSPU activities – one which confronted the virulence of representations of female nudity by male artists.[5]Nevertheless, this argument was made by Richardson in 1952 over thirty eight years after her attack, lessening its potential impact in the feminist narrative of 1914.[6] While the Manchester iconoclasts attacked representations of femininity as well as landscapes, religious paintings, and portraiture, their protest provided the stimulus for iconoclasms against the male gaze. Eight out of the thirteen paintings attacked depict femininity using Victorian stereotypes. Women are either portrayed as reliant (Paolo and Francesca and The Last Watch of Hero); sexualised (Astarte Syriaca); victimised (Syrinx and Captive Andromache); religious (Sibylla Delphica); or as the angel in the house (The Prayer and The Golden Apples of Spring). Their protest, on the one hand, exerted the action and authority generally associated with masculinity. On the other, it simultaneously utilised this ‘male’ energy to dispel imposed readings of womankind in art, museums and politics. In contrast to the assumed passivity of female visitors customarily in the museum, the Manchester suffragettes actively resisted and in doing so instigated the reassessment of a woman’s place in museums both as visitors and painted bodies before Mary Richardson’s more violent rebuttal. The Manchester suffragettes, in targeting these images in particular, enabled representations of female non-conformist behaviour to occupy the museum space and thereby challenged the pedagogical role of art in museums for public learning.

As a site of protest, the museum space embodied the overt sentimentality encouraged by the state (through funding and promotion) for painting the beautiful, while its desecration and ruin symbolised the violations heaped upon women and children by lust, disease, and poverty. In rejecting gendered and cultural ideologies from the Victorian era which continued to suppress female autonomy in the twentieth-century, the Manchester suffragettes sought to undermine the national veneration of male artists and their artworks. In attacking these renowned male artists, the suffragettes succeeded in courting local, regional, national and international publicity for their cause. Thus, while iconoclasms in 1914 have primarily informed scholarly and public discussions regarding suffrage militancy against art, my research contends for their recontextualization in reference to this earliest attack and its reverberating influence.

You can find out more about the full extent of the Manchester iconoclasm in Gursimran’s forthcoming chapter ‘Victorian Paintings Under Attack: The Earliest Act of Suffrage Iconoclasm (1913)’ published in Women’s Suffrage in Word, Image, Music, Stage and Screen: The Making of a Movement (2020). Gursimran has also published on the suffrage attack via Watts Gallery – Artists’ Village: https://www.wattsgallery.org.uk/about-us/news/protesting-watts-origin-suffrage-iconoclasm/. If you’re interested in learning about the transnational impacts of the Manchester iconoclasm, Gursimran’s doctoral dissertation which examines the international reception and appropriation of G. F. Watts’s artworks by activists is forthcoming.[7]

About the author

Gursimran Oberoi is conducting an AHRC-TECHNE and NPIF funded Collaborative Doctoral Award with the University of Surrey and Watts Gallery – Artists’ Village. Her research project, entitled Global Watts: Allegories for All, provides a comprehensive assessment of the international importance and influence of British artist George Frederic Watts (1817-1904). It specialises in the exhibition, circulation and dissemination of Watts’s allegories, elucidating the effects of these transnational engagements on Watts’s legacy as utilised by activist individuals, groups and campaigns from 1880 to present day. Key movements include international Women’s Suffrage, Indian Independence and African-American Civil Rights. Gursimran is Chair of the Doctoral and Early Career Research Committee and Network (DECR) at the Association For Art History.

References

[1] Tickner, Lisa. 1988. The Spectacle of Women: Imagery of the Suffrage Campaign 1907–14. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

[2] Crawford, Elizabeth. 2001. The Women’s Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide 1866-1928. London and New York: Routledge. Ward, Chloe. 2018. ‘Images of empathy: Representations of force feeding in Votes for Women’. In Suffrage And The Arts: Visual Culture, Politics and Enterprise, edited by Miranda Garrett and Zoe Thomas. pp. 249-272. London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts.

[3] The Guardian. 1913. ‘Art Gallery Outrage’. 5 April 1913. MCAG Archives, Manchester Press Cuttings 1912–13.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Fowler, Rowena. 1991. ‘Why Did Suffragettes Attack Works of Art?’. Journal of Women’s History 2, no. 3: 109–25. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/jowh.2010.0130. Mohamed, Lina. 2013. ‘Suffragettes: The Political Value of Iconoclastic Acts’. In Art Under Attack: Histories of Iconoclasm, edited by Tabitha Barber and Stacy Boldrick. pp. 114–124. London: Tate Publishing. Scott, Helen E. 2016. ‘“Their Campaign of Wanton Attacks”: Suffrage Iconoclasm in British Museums and Galleries During 1914’. The Museum Review 1, no. 1. Accessed 12 October 2018. http://articles.themuseumreview.org/vol1no1scott. Nichols, Kate. 2016. ‘Arthur Hacker’s “Syrinx” (1892): Paint, Classics and the Culture of Rape’. Feminist Theory 17, no. 1: 107–26.

[6] Richardson quoted in Nead, Linda. 1992. The Female Nude: Art, Obscenity, and Sexuality. London: Routledge, p. 37.

[7] Oberoi, Gursimran. forthcoming 2021. ‘Global Watts: Allegories For All, 1880–1980’. PhD diss., University of Surrey and Watts Gallery–Artists’ Village.