Sex/Gender/Work: Samak Kosem’s Chiang Mai Ethnography (2017-present)

[This blog post was commissioned by The Courtauld’s Gender & Sexuality Research Group, published 17 September 2020]

Along with Bangkok and Phuket, Chiang Mai is one of Thailand’s most popular destinations for gay sex tourism.[1] Its many gay bars and massage parlours are often staffed by Burmese migrant workers, particularly from Shan State.[2] Recently I have been researching Chiang Mai Ethnography, a project by the Thai artist and anthropologist Samak Kosem (b. 1984, Bangkok).[3] An ongoing project begun in 2017, Chiang Mai Ethnography develops Samak’s ethnographic research on a group of Shan men, originally from Myanmar but now working in gay massage parlours in nearby Chiang Mai. Many of them have girlfriends in the city or at home. Their clientele consists mainly of middle-class Thai men, but it also includes tourists from the West and from East-Southeast Asia, for whom, erroneously or otherwise, Thailand remains a ‘gay paradise’.[4] Chiang Mai Ethnography currently consists of several short videos (brought together under the title I don’t have an ID but I have my body); a series of photographs of a massage parlour, annotated with fieldnotes in Thai (Ethnography of the House); and two framed bedsheets (Not Belonging).[5] I have found myself drawn to this project because of the challenges it poses to hegemonic representations of masculinity, sex work, and migrants, areas of research relevant to my PhD.

To my mind, Chiang Mai Ethnography presents two different but overlapping articulations of masculinity: one, the exoticised and commodified of Shan hypermasculinity sought by the parlours’ Thai clientele; the other, the masculinity cultivated within the community of men during their leisure time. The photo series turns a lens on the former. It presents us with the tools used to craft and maintain this image, through photographs of weights machines and dumbbells scattered on the floor and, in the fieldnotes underneath, references to the use of Viagra (Fig. 1). In their evocation of strength, domination, and sexual prowess, Samak’s photographs present an articulation of Asian masculinity that is not beholden to mainstream Euromerican visual culture, which has tended to portray Asian men as desexualised, feminised, infantilised, and even sickly.[6] Yet this articulation of masculinity is not shown to be any more ‘authentic’, any less racialised or ethnicised, or any less imbricated in webs of power and capital, even though it might also be described as queer.[7] Derrida might describe the gym equipment and Viagra as ‘supplements’ to a supposedly natural, essential, and pre-existing masculinity: on the one hand, they seem to add to or enhance what is presumed to be already there (Viagra is a performance-enhancing drug, after all); on the other, they come to replace and constitute what they supposedly stand in for.[8] Tellingly, the photo series does not put the men’s bodies on display; masculinity is nowhere to be found apart from in the tools that allegedly enhance it.

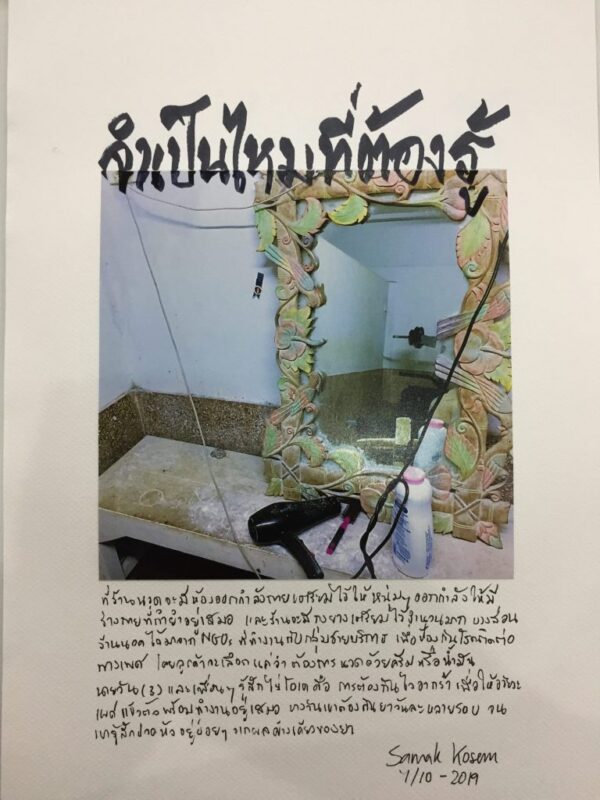

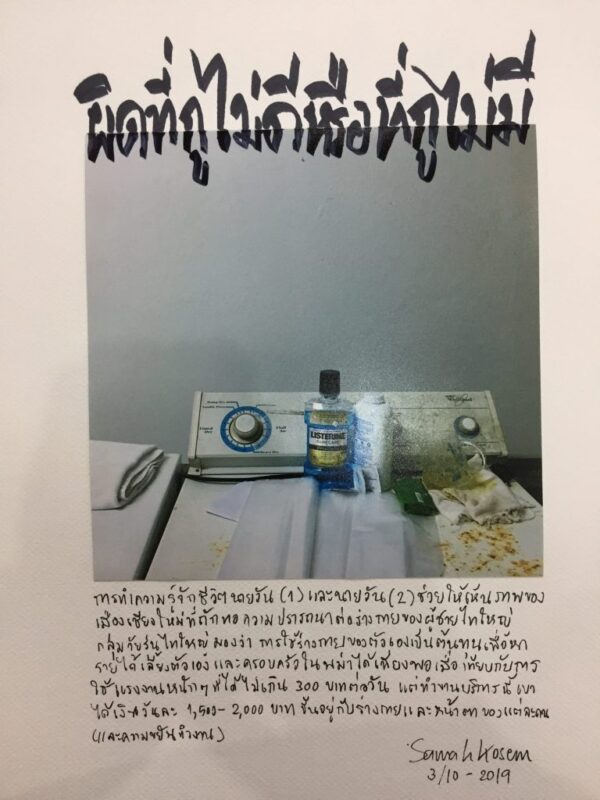

Other photographs in the series further detail the labour involved in crafting this image of masculinity. One photo displays a hairdryer, a brush, and a bottle of talcum powder in front of a mirror, while another shows yet more talcum powder on top of a rusted laundry machine next to a bottle of Listerine and some bleached white sheets (Figs. 2 & 3). Typically, femininity—not masculinity—is associated with masquerade, artifice, and surface, and women’s bodies are considered ‘volatile’, disobedient, and ‘leaky’.[9] But here, masculinity is cosmetic, achieved through the sculpting of the hair (intimated in the sight of the hairdryer and the mirror) as well as the body (the gym equipment). Meanwhile, the idea that the men’s bodies are unruly and ‘leaky’ is suggested in the recurring bottles of talcum powder for absorbing sweat, and the bottle of Listerine, which ‘bleaches’ the mouth clean, like the crisp white sheets next to it.

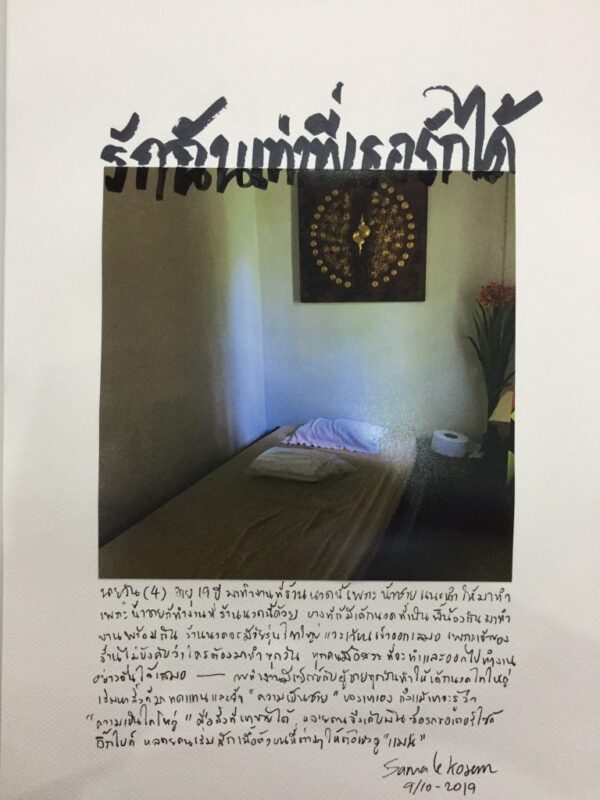

The photo series maps the space of the massage parlour and presents the commodified and exoticised Shan masculinity which has currency in that space. The videos, on the other hand, map spaces of leisure—a gym, a karaoke bar, a football pitch, an outdoor games area—and unlike the photo series, the videos feature the men themselves, working out, singing Shan songs, and playing football and pool with Shan friends (Figs. 4–6). The massage parlour appears dingy, with many of its cramped spaces lit by a clinical bright light or left in shadow; the absence of people makes the space feel ghostly. By contrast, the places depicted in the videos are populated and lively. The football pitch is located outside and feels open, and though they are interiors, the gym and the bar are lit more warmly than the parlour. The men seem unguarded and unaware of the camera’s gaze, which often lingers on the details: a hand flicking through a book of Shan songs at the karaoke bar, a man guarding the goals on the pitch, another flexing as he lifts weights. It is tempting to describe the masculinity on display here as somehow more ‘authentic’ than the image of Shan masculinity that the men leverage in the massage parlour. But the connections between the photo series and the videos muddle such a reading, in particular the repeated displays of gym equipment and weightlifting. The fieldnotes under the photographs recount that with their savings, the men get tattoos and motorbikes to ‘man-up [sic]’. The motivation behind this ‘manning-up’ is left to the assumptions and guesses of the viewer: the men’s actions could be a means of appealing to their clientele, or of consolidating a masculine identity more closely aligned with heterosexuality as a response to the supposedly feminising labour of sex work, or else an expression of some inherent masculine identity.[10] Clear-cut distinctions between a performative masculinity and an ‘authentic’, unperformed masculinity go up in smoke.

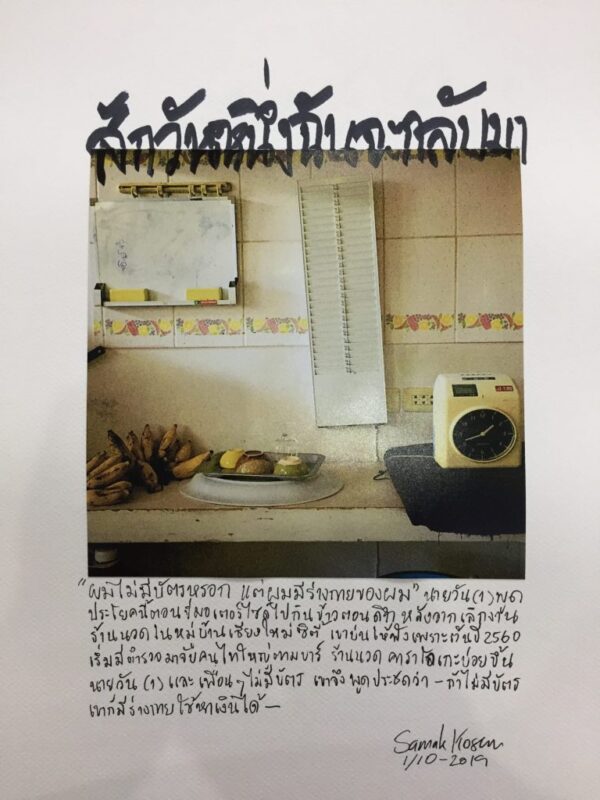

Beyond its representation of masculinity as contingent, crafted, and contested, Chiang Mai Ethnography also interests me because of its portrayal of sex work in a particular locale. Rather than sensationalising, spectacularising, or moralising, the project paints a complex and at times mundane picture of the work undertaken by the men. Sex work has its upsides: the fieldnotes state that the men can earn almost seven times as much money in the massage parlour than in other forms of work available to them as migrants, and that some parlours afford the men considerable freedom, allowing them to decide when and how often to work. Equally, some of the men complain about being expected to orgasm several times a day or the discomfort of taking Viagra. The images of the parlour accompanying the fieldnotes display not just the massage room, but also other rooms, including a kitchen, a laundry room, and a gym space. By presenting us with a neatly aligned row of images of empty rooms, the photo series shifts our attention away from the presumed site of the sex act (the massage room) and resists spectacularising sex work for our consumption (Fig. 7). This also disperses the labour of sex work across the space of the parlour, rather than concentrating it in the sex act. This dispersion is also effected through details, within particular images, familiar to all workers: the clock in the kitchen counting down the workers’ shifts (Fig. 8); the timesheet clocking them in and out; a weights machine tucked surreptitiously next to some sofas (Fig. 1, far left). Here I am reminded of Paul Preciado’s idea of the ‘pornification’ of all labour: that in the twenty-first century, the conditions typical of sex work—‘lack of security, sale of corporal and affective services at a low price, social devaluation of the body that performs the work, exclusion from the right to residency’—are, increasingly often, structurally implicit in many other types of work.[11]

Notably, the portrayal of the men’s experiences in Chiang Mai Ethnography differs starkly from their representation in mainstream contemporary Thai culture and politics. The Burmese have historically been figured as Thailand’s enemies. But as Chairat Polmuk has noted, recent political and economic changes in Thailand have led both to a greater legal and social recognition of migrant workers, and to a shift to depicting these workers as willing participants in public life and beneficiaries of the kindness and compassion of the state and its Thai subjects.[12] In turn, however, these shifts have masked new forms of oppression. For instance, migrant workers who choose to undergo the costly and time-consuming process of obtaining documents are opened up to more restrictive forms of governance and control.[13] Concurrently, the state’s recently launched ‘Happiness Project’, intended to ‘return happiness to the people’, has begun to imagine the integration of migrants in its vision of national happiness. The project has resulted in billboards reading ‘Returning Happiness, Creating Smiles for Alien Workers’ and the establishment of ad-hoc registration centres to more effectively monitor migrant populations.

In this context, the men who appear in Samak’s project can be understood, at least in part, in terms of what Sara Ahmed has called ‘affect aliens’. Ahmed writes that one ‘can be affectively alien by placing their hopes for happiness in the wrong objects, as well as being made unhappy by the conventional routes of happiness’.[14] Samak’s fieldnotes inform us that at least some of the men do not have documents: perhaps they have, like many others, refused the ‘happiness’ and precarious status promised by legal routes, including the lower pay, restricted freedom, and greater susceptibility to employment rights abuses that legalised migrants reportedly experience.[15] The men’s experiences of the pleasures and challenges of their residence in the country also renders them affectively alien. In contrast to the claims made on billboards, the smiles of the ‘alien workers’ glimpsed in the video series are not bestowed by the state: instead, they seem to arise from the migrants’ self-organised networks of camaraderie and information exchange (Figs. 9 & 10). Samak’s fieldnotes inform us, moreover, that these workers feel ‘alienated’ and ‘other’. The first image in the photo series bears the title ‘One Day I Will Come Back’, overlaid onto the image of the massage parlour kitchen, imbuing it with a longing for home. In the fieldnotes beneath another image, one of Samak’s informants mentions his ‘homesickness’. Hints of melancholy and homesickness also surface in the video of the men plaintively singing Shan songs. These same affects pervade the framed bedsheets taken from the massage parlour and inscribed with the names of the men’s hometowns written in Burmese (Fig. 11). The sheets’ folds, creases, and furrows, mottled with dark or worn patches, evoke mountains and rivers seen from a bird’s-eye-view. The bedsheets are ‘unhappy objects’, to use Ahmed’s term, bearing witness to the men’s enduring attachment to, and orientation towards, elsewhere.

But what happens—or doesn’t happen—when art featuring ‘affect aliens’ appears in the art gallery, museum, or festival? This is a central question of my thesis, and one I want to consider more closely as I develop my thinking about Chiang Mai Ethnography. Representations of these bodies are ever more ubiquitous in the gallery, museum, or festival: the 2018 Bangkok Biennale, for example, featured several works about migrants and sex workers in the country.[16] Making marginalised communities visible in this way is often framed as a means of raising awareness and promoting understanding, which are of course important goals. But to my mind, any attempt at visibility must also contend with the capitalist and colonising logic of spectacle, of offering up marginalised bodies and lives for the consumption of art publics and collectors, for a profit, whilst doing little to change marginalising, oppressive systems. Such attempts must also negotiate state agendas. These may include the desire to exhibit progressiveness and ‘tolerance’ to attract foreign investment and gain access to transnational networks of capital, without bestowing full citizenship to those who are ‘tolerated’; or to smooth other the creases of discontent and perform national happiness.[17] For the most part, Samak’s project resists spectacularising sex work or presenting the migrant workers as benefitting from or in need of the particular kind of happiness that the Thai state offers them. In so doing, it acts as a poignant reminder to think critically about regimes of visibility and happiness, and their connections to capital and control.

About the author

Andrew Cummings is a PhD candidate at the Courtauld Institute of Art and Tate. Their doctoral research project examines the portrayal and currency of the ‘alien’ in global contemporary art, focusing on art by queer artists working across East and Southeast Asia.

References

[1] I would like to thank Samak Kosem for his generous discussions during my preparation for this blog post, and for granting all image permissions.

[2] See Jan W. De Lind van Wijngaarden, ‘Between Money, Morality and Masculinity’, Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, Vol. 9, Nos. 2-3 (1999), pp. 193-218; and Jane M. Ferguson, ’Sexual systems of Highland Burma/Thailand: Sex and gender perceptions of and from Shan male sex workers in northern Thailand’, South East Asia Research, Vol. 22, No. 1 (March 2014), pp. 23-38.

[3] Hereafter I refer to the artist using his first name in accordance with conventions in Thai and related scholarship.

[4] Peter Jackson, ‘Tolerant but Unaccepting: Correcting Misperceptions of a Thai “Gay Paradise”’, in Peter Jackson and Nerida Cook (eds.), Genders and Sexualities in Modern Thailand, Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books (1999), pp. 226–242.

[5] Outside of Thailand, displays of the work have included English translations. The translations I have used for this blog post can be found in the exhibition catalogue Phantoms and Aliens: The Invisible Other, Kuala Lumpur: Richard Koh Fine Art, 2020.

[6] Note, as well, that the articulation of butch masculinity is less neatly tethered to heterosexuality than in many Western countries: as Jackson notes, the Thai expression for ‘a real man’, phu-chai roi persen (lit. ‘100% man’), first connotes butch masculinity and only secondarily connotes heterosexuality. Peter Jackson, ‘An Explosion of Thai Identities: Global Queering and Re-Imagining Queer Theory’, Culture, Health & Sexuality, Vol. 2, No. 4 (Oct–Dec 2000), pp. 405-424. For more on the pathologisation of East-Southeast Asian bodies by the West, see Ari Larissa Heinrich, The Afterlife of Images: Translating the Pathological Body Between China and the West, Durham, NC: Duke University Press (2008); for more on feminisation and infantilism, particularly as these relate to homosexuality, see Eng-Beng Lim, Brown Boys and Rice Queens: Spellbinding Performance in the Asias, New York: NYU Press (2014).

[7] It is ‘queer’ in its connection to non-normative sexual practices. Of course, other aspects of this masculinity seem at odds with an anti-racist, anti-capitalist articulation of queer politics.

[8] Jacques Derrida, On Grammatology, trans. Gayatri Spivak, Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press (1997).

[9] See Margrit Shildrick, Leaky Bodies and Boundaries: Feminism, Postmodernism, and (bio)ethics, New York and London: Routledge (1997); and Elizabeth Grosz, Volatile Bodies: Towards a Corporeal Feminism, Bloomington: Indiana University Press (1994).

[10] Victor Minichiello and John Scott discuss the ‘double stigma’ that male sex workers can face, both because of their ‘deviant’ sexual practices and for their participation in the ‘feminised practice’ of sex work, construed as a form of care. Victor Minichiello and John Scott (eds.), Male Sex Work and Society, New York: Columbia University Press (2014).

[11] Paul B. Preciado, Testo Junkie: Sex, Drugs, and Biopolitics in the Pharmacopornographic Era, trans. Bruce Benderson, New York, NY: The Feminist Press at the City University of New York (2013), p. 296.

[12] One such political-economic shift that Chairat pinpoints is the establishment in 2015 of the ASEAN Economic Community (of which Myanmar and Thailand are both members). This has deepened optimism regarding transnational co-operation, led to greater social and legal recognition of migrant workers whose numbers are increasing with labour demands, and consolidated frameworks for the biopolitical control of migrant populations. Chairat Polmuk, ‘Labor of Love: Intimacy and Biopolitics in a Thai-Burmese Romance’, in Samak Kosem (ed.), Border Twists and Burma Trajectories: Perceptions, Reforms, and Adaptations, Chiang Mai: Centre for ASEAN Studies, Chiang Mai University (2016), pp. 299–319.

[13] Indre Balcaite’s study of Burmese migrants to Thailand belonging to another ethnic group to the Shan points out the similarities between ‘legal’ and ‘illegal’ means of entering the country, and the relative demerits of the former, from the migrants’ perspective: ‘migration services are a commodity where legality comes at a high premium and at the expense of personal freedom. Undocumented migrants who can rely on their own networks for finding jobs in Thailand enjoy more flexibility, including the possibility to “legalise” after arrival’, p. 47. Indre Balcaite, ‘Brokered (Il)legality: Co-producing the Status of Migrants from Myanmar to Thailand’, in The Migration Industry in Asia: Brokerage, Gender and Precarity, London: Palgrave Macmillan (2020), pp. 33–58.

[14] Sara Ahmed, The Promise of Happiness, Durham, NC: Duke University Press (2010), p. 115.

[15] Balcaite, ‘Brokered (Il)legality’, p. 37.

[16] Rina Chandran, ‘Migrants, sex workers take pride of place in Bangkok art festival’, Reuters.com, 25 October 2018, available online at https://www.reuters.com/article/us-thailand-art-rights/migrants-sex-workers-take-pride-of-place-in-bangkok-art-festival-idUSKCN1MZ10D(accessed 10 September 2020).

[17] ‘Performing’ harmony here has the sense of Sara Ahmed’s ‘non-performative’: that which does not bring into being what it claims to. Sara Ahmed, ‘The Non-Performativity of Anti-Racism’, Meridians, Vol. 7, No. 1 (2006), pp. 104–126. For more on the Thai government’s recent interventions into and uses of contemporary art for its own political ends, see Pandit Chanrochanakit, ‘Deforming Thai Politics: As Read through Thai Contemporary Art’, Third Text, Vol. 25, No. 4 (2011), pp. 419–429; and Thanavi Chotpradit, ‘Of Art and Absurdity: Military, Censorship, and Contemporary Art in Thailand’, in Journal of Asia-Pacific Pop Culture (2018), pp. 5–25. For more on state agendas and queer visibility in a context outside of Thailand, see Audrey Yue, Queer Singapore: Illiberal Citizenship and Mediated Cultures, Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press (2012).