The practice of Ori Gersht (born 1967, Tel Aviv) is rooted in the past. His films and photographic series examine memories of traumatic historical events, filtered through the artist’s personal experience. Gersht’s Evaders (2009), will provide the focus of this study, in which I will establish a framework that locates the film and its accompanying photographic series within the broader concerns of his practice. In Evaders, Gersht traces Jewish-German critic and philosopher Walter Benjamin’s exodus across the Pyrenees via a present-day, fictionalised exploration of his route, as a means to inhabit Benjamin’s experience as a refugee. Gersht employs Benjamin’s passage on the angel of history from the ‘Theses on the Philosophy of History’ (1940) as a motif and introduction to Benjamin’s critical work. Through an analysis of Benjamin’s writing and its influence on the artist’s work, I will formulate an argument grounded in Gersht’s practice of remembrance, and its ethical and aesthetic intersection with Benjamin’s concept of history.

Introduction

A beleaguered man struggles against the howling wind on a desolate mountain path. To his right, a spectral figure fades in and out of the wilderness. Ori Gersht’s Evaders (2009), a dual-channel film and photographic series, reimagines Walter Benjamin’s flight through Vichy France into Spain along the precipitous route traversed by political dissidents and figures of the European Jewish intelligentsia during the Second World War.

In this article I trace the journey taken by Benjamin in 1940, and the resonance of this period of political and cultural upheaval on Gersht’s art and his identity in the twenty-first century. A complementary analysis of the artist’s work in film and photography will illuminate the focus of this study. Gersht’s practice operates at the crossroads of memory, history and geography. It hinges on an appraisal of dichotomous themes, primarily those of beauty and violence, and of the physical and metaphysical as a consideration of the ideological divide in Benjamin. Another prevalent concept is that of memory’s resonance in historically charged landscapes, and its erasure – an obliteration that Gersht considers in parallel with the degradation of photographic media, and Benjamin’s own philosophy of history. This will be the first sustained attempt to locate the intersection of Benjamin’s work with Gersht’s broader practice and portrayal of the philosopher.

The fractured schools of thought on the unifying characteristics and alignment of Benjamin’s shifting body of work are also examined, with reference to his colleagues at the Institute for Social Research in Frankfurt, and his close friend, theologian Gershom Scholem. I turn to more recent criticism, including that of Esther Leslie and Susan Buck-Morss, in further clarifying Benjamin’s methodological approach and his attempts to reconcile historical materialism with Judaic messianism. I investigate the melancholy strains of thought in Benjamin, and what this suggests about his political position – was a nihilistic temperament to blame in a seemingly passive political engagement, or did this instead manifest as a practical pessimism? Finally, I touch upon the situation of Gersht’s work in a post-Holocaust context, and his use of Benjamin as a link across history to the fate of the contemporary refugee and stateless individual.

Evaders the film opens in a hotel room, one seemingly dislocated from time and space – a stand-in for the room in Portbou, Spain, where Benjamin took his own life after being denied transit to Portugal.[1] Gersht’s Benjamin (actor Clive Russell) sits at the edge of a bed with his back turned to the viewer, as a voiceover bleeds in, reading the passage on Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus (1920) from Thesis IX of Benjamin’s ‘Theses on the Philosophy of History’ (hereafter, ‘Theses’):

A Klee painting named Angelus Novus shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. This storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.[2]

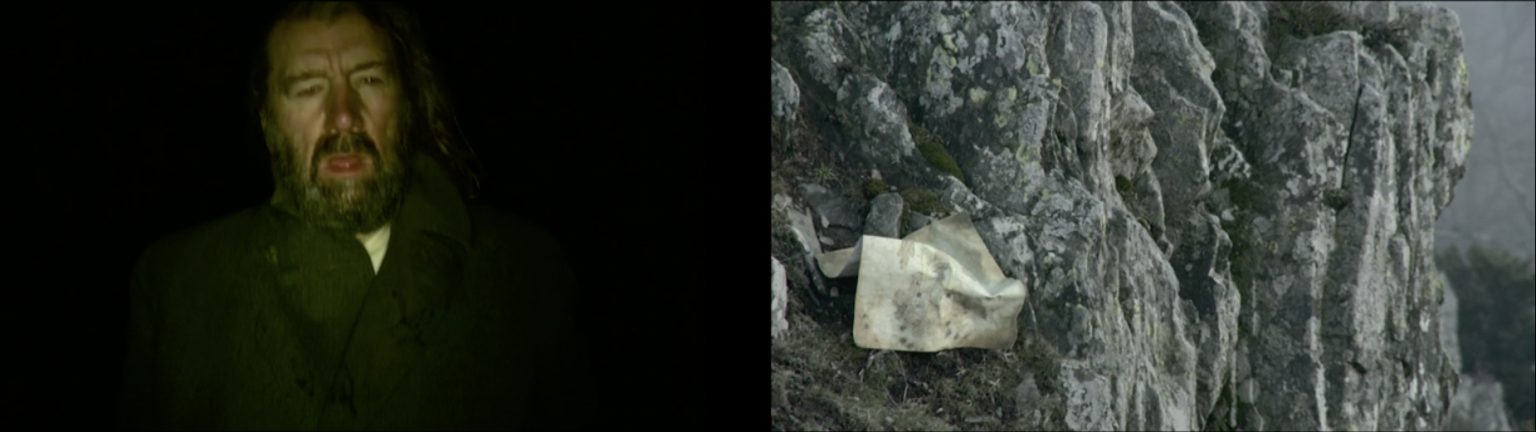

This passage foreshadows Benjamin’s journey across the inhospitable Lister Route, in the non-linear sense of the film’s progression. From a chronological standpoint, Evaders begins at the end of Benjamin’s story. We witness Benjamin embark upon his arduous journey as the screen divides into two. This split screen distills the essence of Gersht’s artistic practice – the intense physicality of the left screen acts as counterpoint to the painterly, symbolic landscape on the right (Fig. 1). A storm builds in the distance as daylight fades – this encroaching tempest is a harbinger of progress, and of Benjamin’s ultimate fate. The Romantic landscape on the right is punctuated by the appearance of an anonymous figure, with his back turned to us, dissolving into the snow-laden landscape (Fig. 2). Is this apparition Benjamin from the beyond, haunting the European landscape, or even a manifestation of the angel of history, with his back turned to the future? The angel is located at the heart of both ‘Theses’ and Gersht’s Evaders. The artist explores its allegorical function in parallel with Benjamin’s final journey, in which the philosopher himself ‘becomes an angel for Gersht, an icon at once authentic and fantastical’.[3]

Remembrance and Obliteration

Benjamin’s late work is consumed with the threat of the erasure of the nameless masses from history. Gersht also contemplates temporal themes of recording and erasure, and in parallel, remembrance and amnesia. As I shall argue, his analysis of the chemical and physical degradation of the photograph stands as a metaphor for the obliteration of memory, and by extension, history. The perceived inadequacy of both film and human memory as reliable and lasting means of commemoration provides a vehicle for Gersht’s study of the catastrophes of the twentieth century.[4]

The spectral pallor of Evaders is echoed in Gersht’s photographic series White Noise (1999–2000, Fig. 3) and Liquidation (2005). These experiments with analogue film render snatched scenes of snow-covered central Europe with a painterly, transient abstraction. White Noise explores the ghostly indeterminacy of memory in its long exposures, taken on board a train from Krakow to Auschwitz – the obscured view of the landscape replicates that of the Jews on the Holocaust trains of the Reichsbahn, and alludes to the attempted erasure of a people. The Ukrainian landscape depicted in Liquidation is ‘all but completely elided, almost utterly white’ – this erasure could be equated not only with the onset of collective amnesia, but with an almost violent obliteration on the part of the landscape, which leaves no geological record of the atrocities it has witnessed.[5] Gersht notes that ‘entire communities were liquidated, but there was no trace of this in the forest’ – a community that was once home to his wife’s relatives.[6] To Liz Wells, ‘the suggestion that nature literally absorbs history through the soil connects with the idea of a collective unconscious’.[7] Gersht’s depiction of landscape operates on an acutely personal level. Its biographical content establishes ties with a broader historical framework, tracing the convergence of personal and cultural perspectives on landscape.

Snow is a recurring element in Gersht’s work. Associated with blanketing and erasure, it creates a tabula rasa of history and landscape, primed for the projection of the artist’s narrative. It serves a literal function in the torturously circuitous Will You Dance for Me (2011, Fig. 4), which elliptically sketches out the testimony of an Auschwitz survivor-turned-dancer. Forced to stand overnight in the snow after refusing to dance for her captors’ entertainment, Yehudit Arnon vows that if she survives, she will become a professional dancer. Gersht depicts a distinctly physical ordeal endured at the hands of the elements, similar to that experienced by Benjamin in exodus, as portrayed in Evaders. Arnon’s physicality is etched onto the screen as she oscillates in and out of view, from light to darkness. The pull between presence and absence is keenly felt in Gersht’s work, as seen in Benjamin’s abandoned suitcase, hidden among the rocks in Evaders. This tension functions by turns as an affirmation of what remains, a warning of what could yet be lost, and an attempt to represent the inconceivable, as I shall discuss in greater detail, in the context of the death of figuration in post-Holocaust art.[8] To Hava Aldouby, Gersht employs physical presence as an antidote to the absence of exile and death: ‘the artist strives to wrest the event from the evasiveness of memory, endowing it with an experiential immediacy’.[9]

Gersht’s Ghost (2004) series of overexposed photographic prints, depicting mature olive trees in the contested territory of the Galilee, are an example of his experiments with the physical degradation of film, and a material form of erasure. Having allowed the negatives to become severely burnt out by the sun following day-long exposures, Gersht subsequently attempted to salvage what little information could be gleaned from the destroyed film. This process was initially intended as a violent intervention, but in his final prints, Gersht found that a delicate presence was born out of the film’s destruction: ‘a kind of halation, an effect well known in the nineteenth century and of interest to photographers and painters’.[10] Gersht states that ‘the trees were there before the Ottoman occupation and British Mandate and before the current conflict’.[11] The trees here function as a metaphor for Palestinian resilience, and attend to the concept of the landscape as witness to history.

From analogue destruction we move to the degradation of the digital image and its material limits in Gersht’s heavily pixelated Chasing Good Fortune (2010), a series of photographs of Japanese cherry trees in blossom. These trees have managed to flourish against the odds in the irradiated soil of Hiroshima, while their delicacy confounds their historically militaristic connotations. Beauty, and thereby hope, is borne out of a history of violence. The data possessed by a high-definition digital photograph is both vast and precisely quantifiable, making it highly susceptible to degradation in its reproduction. Gersht exploits this digital indeterminacy by ‘working on these edges of photography, either to employ so much information or reduce information to the point of collapse’.[12]

We witness a similar examination of the plasticity of the digital medium and its capacity to capture unseen fragments of time in Gersht’s Big Bang series (2007). Floral arrangements modelled on still lifes by Jan van Huysum and Theodore Fantin-Latour were rigged with a series of hidden explosives. At the point of detonation, a camera captured the unpredictable nature of the event at a rate of 1600 frames per second. This creates the effect of a slow-motion film, which is in fact comprised of many frozen images, indicative of ‘the flow of movement and its sudden arrest’.[13] Gersht likens this expansion from the individual singularity of the explosion, as the fragmented petals settle and normality resumes, to an ‘expansion of our notion of truth’.[14] The unpredictable nature of this experiment endows it with an element of chance, redolent of surrealist automatism and Benjamin’s ‘unconscious optics’.[15]

Gersht’s fascination with erasure, chance and fragmentation can be traced directly to Benjamin’s modernist reconfiguration of history. I refer specifically to the flashing dialectical image, which is contingent on an element of chance in its algorithmic function and is thus distinct from binary Marxist dialectics. Benjamin employed this device in ‘Theses’ and his Arcades Project (1940) via aphorism and quotation (a dialectical image could take myriad forms, be it a memory or a work of art), described by Susan Buck-Morss as ‘a visual, not a linear logic: the concepts were to be imagistically constructed’.[16] The dialectical image was an agent in Benjamin’s vivid transfiguration of revolutionary politics, his conception of history that unravelled from the present. The realisation of Benjamin’s materialist revolution (or messianic redemption) hinged on the fluid, fortuitous intersection of these cultural fragments; on the tenuous capacity of images in the present to strike up a redemptive conversation when juxtaposed with those of the past. As articulated in ‘Theses’, ‘the past can be seized only as an image which flashes up at the instant when it can be recognized and is never seen again’.[17]

In Gersht this occurs both as deliberate montage in Evaders’s ‘dialectic of the two screens’ and in the sudden, involuntary rupture of Big Bang, which yields a new, reconstructed image.[18] His practice operates on the basis of the ‘current event existing in parallel to events of the past’.[19] Buck-Morss has compared this flash to that of a camera, facilitating redemptive illumination – Benjamin takes the photographic metaphor further in the Arcades Project, likening his dialectical images ‘to those which are imprinted by light on a photosensitive plate’.[20] Benjamin hoped that, once wrenched out of their historical context, memories of failed revolution would foment political upheaval in the present, subverting positivist historicism to ‘blast open’ the historical continuum itself, thereby delivering a transfigured society.[21] His concept of revolution did not break with history itself, but with the ideological progress of historicism, which ‘can only be sustained by forgetting what has happened’.[22] The new classless society would not follow a hypocritically revisionist model, which Benjamin saw as leading to a hollow semblance of true society.[23]

Gersht himself is acutely aware of the capacity of photographs to rewrite history, and the inherent danger therein. His still photographs from Evaders, such as Far Off Mountains and Rivers (2009, Fig. 5), self-reflexively explore this aspect from the perspective of the digital, with its enhanced ability to augment and distort. The photographs are digital composites, ‘refutations of the visual and of themselves’, and have been constructed as a means of questioning the veracity of testimony, the reliability of memory, and the construction of truth and myth that surrounds Benjamin’s final days.[24] Any seemingly involuntary, unconscious elements in the photographs and film are in fact highly orchestrated, even theatrically referential. The black briefcase, purportedly containing Benjamin’s lost manuscript, is hidden in plain sight in Far Off Mountains and Rivers. It is a sort of constructed punctum, as distinct from the inadvertent shock that Barthes locates in photographs that have an unidentifiable pull on the viewer.[25] The briefcase also functions as a historical prop, an intrusion that undercuts the harmony of the image, in correspondence with Gersht’s interest in ‘the space between the visual and the lingual, between what one sees and what one knows’.[26]

The aforementioned expansion practiced by Gersht is witnessed in Benjamin’s theory of the optical unconscious, in which the moving image is endowed with the capacity to reveal truths hidden from the naked eye: ‘with the close-up, space expands; with slow motion, movement is extended’.[27] Gersht extrapolates these unseen optics in the manipulation of his medium. He mobilises the capability of the photographic medium not only to distort and construct truth, but also to reveal subliminal moments, involuntary memories or, indeed, dialectical images. The ‘revelation’ or punctum recorded by the camera, as described by Gersht, itself has a ‘power of expansion’.[28] This is revealed in the freeze frames of Big Bang, which establish a dialogue between the initial explosion and the point at which the debris settles. In Evaders we witness the landscape unravelling in unnerving time lapse – in this instance time is not expanded but condensed; the encroaching storm is endowed with an exaggerated menace.

With reference to the revelatory capacity of Gersht’s work, Wells observes that his photographs ‘appear as images removed from the flow of time.’ She does, however, point out that this ‘over-simplifies the fluidity of the interrelation of imagery, personal recollection and collective history. Indeed, imagery may reconfigure memory’.[29] As we have seen, this can have both a negative implication in the distortion of truth and a redemptive function in realising the revolutionary potential of the past. Benjamin’s practice of remembrance and resistance to erasure is kept alive in Evaders’ portrait of the philosopher, reconfigured through the artist’s contemporary lens.

Allegory and Ideology

Gersht’s technique illuminates his conceptual and ethical concerns. On the left-hand side of Evaders’ split-screen format, we witness a material representation of the figure, and on the right, a spectre dissolving into a fantastical landscape of art historical allusion. Gersht employs the montage of the dual screen to articulate the ‘tension that exists between messianic time, and a materialistic account of historical progress’.[30] This is intimately tied to Benjamin, and the competing ideological strands in his writing.

Benjamin felt politically alienated in the tumultuous climate of Weimar Germany – if he saw anything of Germany in himself, it was in its culture, and in European culture as a whole – Baudelaire and Goethe were formative influences on his thought.[31] During his exodus from Berlin to Paris in the late 1930s, he witnessed Europe in decay, crushed by the force of fascism. To Benjamin, all past attempts at revolutionary thought had failed, not only in allowing the ascendance of fascism through a ‘stubborn faith in progress’ and technocratic thought, but worse yet, in appearing to collude with it.[32] A committed if thoroughly unorthodox Marxist since the late 1920s (or, to Michael Taussig, a ‘Proustian Marxist’), Benjamin had long struggled with the Soviet model.[33] His ‘Theses’ were a response to this disillusionment in their search for an alternative philosophy of history.[34]

Benjamin specifically took issue with the ideologically progressive nature of so-called vulgar Marxism, and its homogenous, linear conception of history. To Benjamin, this conviction was untenable; he was living daily with this failed hope. What was needed, in his view, was a different model of historical materialism, one representative of the complex, conflicted times in which he lived. Benjamin viewed his Marxist inclinations as part of his experimental approach to history, akin to his dabbling in Jewish mysticism under the influence of Gershom Scholem.[35] It has been suggested that Benjamin’s model was one with no real political praxis in its uncertain application of Marxist ideology.[36] His method resembled a ‘wager’ – a critique based in a negative appraisal of ideology – that had the capacity to yield a revolutionary moment, but that could equally fail at any time.[37] Its revolutionary promise was laden with unstable hope, located in the shadow of history’s canonical achievements, and enacted by Benjamin’s conception of the historical materialist, who ‘regards it as his task to sweep history against the grain’.[38] The aspect of nihilism and Blanquist anarchism that has been attached to Benjamin’s temperament is a part product of his mythologisation as a victim of history, with reference to his ‘saturnine’ frame of mind, and the idea that his fate was inevitable.[39] It would be short-sighted to attribute this melancholy, a product of historical circumstance, to a perceived passivity in Benjamin’s politics. Benjamin acknowledged the value of an active life in the community, removed from the insular world of academia.[40] Furthermore, his ideological scepticism could be viewed as practical in its nuanced, open approach – to Michael Löwy, an ‘organized pessimism’.[41]

Allegory as a distinctly temporal device of juxtaposition pervades Benjamin’s work. It features in his concept of the dialectical image, the aforementioned aphoristic technique that surfaces in the Arcades Project (which Benjamin likens to ‘allegorical dismemberment’) and in the device of the angel of history as messenger in his ‘Theses’.[42] The Arcades Project adopted the microcosm of Haussmann’s industrialised nineteenth-century Paris in constructing a modern parable to ‘break the catastrophic spell of things’ that afflicted the bourgeoisie.[43] Benjamin’s technique of aphoristic montage can be traced to Baudelaire’s correspondences, and to his definition of the ‘ragpicker’ – the collector of the refuse and ephemera of cultural history.[44] Benjamin saw himself as this chronicler of the narratives of the oppressed, that is, the materialist historian, with the forgotten archival fragments of the Bibliothèque nationale de France at his disposal, primed to enact a redemptive discourse with time. It could be argued that Gersht himself functions as a collector, reconfiguring testimonies of twentieth century trauma – as we have seen in works such as Will You Dance for Me – thereby not only redeeming the past, but opening up a conversation in the present; to David Chandler, a ‘dialectical space where ideas ferment’.[45]

Benjamin’s ‘Theses’ came into being as a commentary on the Arcades Project, specifically his text on Baudelaire. He acquired Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus in 1921, and the painting would go on to become symbolic of the critic, and a cipher to his state of mind in the following decades. The angel in ‘Theses’ stares in impotent horror at the accumulating ‘pile of debris’.[46] These ruins of history bear a remarkable similarity to the Kabbalist story of the broken vessels, which must be reconfigured by the angel (who longs to ‘make whole what has been smashed’) if the Messiah is to bring the longed for redemption, or the ‘dialectics at a standstill’ that for Benjamin would signal the revolutionary end of history.[47] Buck-Morss likens the humanist aspect of the Kabbalah to Benjamin’s conception of history, in which the masses are ‘historical agents whose knowledge and understanding of what’s at stake is indispensable’.[48] Benjamin ascribes a similar ‘healing’ capability to film, which, through montage, reassembles the fractured sense of perception caused by industrialisation.[49] In his view, the technique of montage itself fosters an ideal political art, exemplified by the destructive (or deconstructive) impulse of Bertolt Brecht’s allegorical theatre.[50] In both instances, messianic and profane, destructive transfiguration must necessarily prefigure complete redemption.

In ‘Theses’, the angel is involuntarily borne further away from Paradise by the winds of progress, powerless to prevent the tragedy unfolding before him. In Evaders Benjamin too is propelled against his will on his final journey, a reluctant refugee driven onwards by the tramontane wind of the Pyrenees. At one point, we witness the Angelus Novus painting pinned to a jagged outcrop by the destructive storm (Fig. 6). Read against the situation in Europe in 1941, this storm must be seen to allude not only to ideologies of progress, but specifically to the Nazi terror. Benjamin did not live to witness the extent of this industrialised barbarism, a strategy so systematic and choreographed as to acquire a grotesque rationality and beauty in the eyes of its creators.

Aesthetics and Trauma

A central concern in Gersht’s work is that of the tension between beauty and violence, ostensibly a ‘subversive approach to using aesthetics to lure a viewer into dealing with subject matter that’s very difficult’.[51] The technique of seducing an audience with beauty in the context of trauma is troubling in its potential to establish a greater distance between the viewer, the work’s ethical motivation, and its historical causality. In Evaders’ elemental landscapes, sublime terror and delight are engendered in equal measure by distance and monumental, alien beauty.[52] Gersht has attempted to mediate this issue of abstraction, which he acknowledges as being problematic in the context of war and trauma, by punctuating the landscape with referential elements (such as Benjamin’s abandoned suitcase):

I start with the specific, but then I have this desire to universalize it, and to do this I have to lose the specificity … if it falls into pure abstraction it loses all its historical references, so what I try to do in the final stage is to return it to something specific … which could help locate it.[53]

I would argue that the harsh realism in Gersht’s depiction of Benjamin’s physical labour rescues Evaders from overt abstraction more successfully than its literal markers – which have something of the melodrama in their specificity – by asserting the experiential over the intellectual.

The contemplative distance in Gersht’s work is, however, undeniable, and is largely at odds with Benjamin’s advocacy of film as a means to eradicate the void between the auratic artwork and its enthralled audience. Benjamin the modernist regarded film as a mirror to society and as the ultimate means of the masses’ emancipation, as outlined in ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’ (1936). It was to facilitate a ‘tremendous shattering of tradition’, breaking down auratic distance via radical montage, as exhibited in surrealist and early Soviet cinema.[54] The medium was also notoriously exploited in the ‘aestheticised politics’ of Leni Riefenstahl’s propaganda films, and Soviet displays of mass-spectacle could no more be absolved of this manipulative tendency.[55] The entrenched polarity of aura and technology in the ‘Work of Art’ essay ultimately yields, in Benjamin’s view, to a necessary tension between the two, where aura (as experience rather than mere aesthetic commodity) becomes something to be cautiously engaged with.[56] This tension is worryingly absent in a contemporary context, in which aesthetics and technology appear to have broadly fused in a consumer-capitalist media. Despite its prognostic collapse, the fragmentary, indexical format of Benjamin’s method translates seamlessly to digital networks, and indeed, digital modes of art, as opposed to a more traditional (it could be said, analogue) concept of the development of history.[57]

Gersht’s experimentation in the digital realm could be seen as an attempt to reinstate this absent tension, in lieu of eradicating aura. The pull between abstraction and representation also serves to establish an autonomy that is crucial to the singular needs of post-Holocaust art. Henry Pickford considers Theodor Adorno’s Aesthetic Theory (1970) in determining what would constitute an ideal post-Holocaust art. Adorno describes a negative capability located in the autonomous ‘double character’ of art, which to Pickford manifests as a ‘determinacy in [the artworks’] irreconcilability’.[58] Pickford contends that this art cannot be too harmonious in the Hegelian sense – some disconnect and tension is necessary – ‘the successful or “authentic” artwork must both maintain and disintegrate aesthetic semblance.’[59] However, the idea of the Holocaust as unrepresentable, as in Kant’s unfathomable sublime, is concerning. As Pickford acknowledges, ‘the problem is that such a strategy can all too easily fall into theological transcendence or, even worse, an aesthetic myth’ where the Holocaust is located outside of history, causality and agency.[60] In inhabiting this post-Holocaust context, I would argue that Gersht employs beauty not merely to seduce, but in potent defiance of violence and, crucially, as a salve and reprieve from trauma. We are also reminded here of the beauty that often surfaces from moments of utter annihilation, both in Gersht’s experiments with media, and in the sense of messianic creation. Pickford discusses the redemptive will of mournful art, one that aims to ‘recuperate historical loss and suffering through aesthetic means’.[61]

In Evaders, we do not sense an explicit agency, but a burden of responsibility in conveying a collective history of erasure. The landscape is employed as an allegorical device in articulating Gersht’s moral imperative, while the positioning of his art ‘within the framework of the Holocaust…serves him in the construction of a wider range of significations concerning the human and the humane’.[62] A final function of the aestheticisation of the landscape in Evaders is that of introducing important themes of cultural heritage and identity, alluding to Benjamin’s attachment to Europe.

Exodus and Identity

Evaders entwines individual and collective histories: the film’s title itself implies a multiplicity of refugees. Concepts of the Jewish diaspora proliferate in Gersht’s work, largely stemming from his conflicted relationship with Israel: ‘I was attracted to Europe for similar reasons to Benjamin. Culturally, my roots are here. I often think that being Israeli is the abnormality in my family tree.’[63] Gersht’s feeling of connection with Benjamin provides a link to broader issues of identity and migration. The common conception of Benjamin’s melancholic frame of mind attaches a tragic singularity to his demise. I would suggest that his fate was far from unique, but a result of circumstance – Benjamin’s suicide by morphine, for example, was by no means exceptional. American journalist Varian Fry recalled refugees on his list committing suicide following the German invasion of Paris, and those that carried poison vials, ‘just in case’.[64] Fry assisted Lisa Fittko (Benjamin’s guide along the escape route) and her husband Hans in helping over 2,000 refugees escape Nazi-occupied Europe, among them Hannah Arendt, André Breton and Max Ernst. Even those who successfully immigrated to the United States frequently felt a sense of dislocation, precipitated by the trauma of having lived through the great catastrophe of the twentieth century, and a longing for their cultural past. Gersht mentions émigré Stefan Zweig in this context.[65] Distraught at the decimation of European culture and holding out no hope for the future of humanity, Zweig committed suicide abroad in 1942 with his wife.

Benjamin had considered relocating to Palestine (largely at Scholem’s urging) but was both unwilling to leave Europe and could not reconcile his Marxist politics with the Zionist project.[66] Gersht has spoken of the ‘tension that exists between the diaspora and Zionism’ in the idea of a promised land and the crisis of its realisation.[67] Even if Benjamin had successfully fled to New York via Portugal, as was his aim, one suspects that his troubles would not have been resolved. Upon relocating to the United States, Adorno was swiftly deprived of the freedoms that he had initially enjoyed. As post-war optimism yielded to Cold War paranoia, he found himself once more an enemy alien, under house arrest, ‘being asked to subordinate his intellectual activity to the interests of the mass-media industry, composed, then as now, of capitalist monopolies’.[68] Adorno describes the difficulties facing European émigrés in adapting to a society in which everything was appraised in terms of its exchange value: ‘the individualities imported into America…succumbed to the universal mechanisms of competition, having no other means of adaptation to the market…than their petrified otherness’.[69]

This early Jewish diaspora conjures an image of figures in the wilderness, akin to the apparitions that haunt the landscape of Evaders. Benjamin was the stateless refugee whose life (and death) were ultimately determined by borders and checkpoints. Gersht’s identification with Benjamin is rooted not just in a shared cultural history, but also in the act of migration itself, and its accordant anxiety. This manifests for Gersht in his recurrent travels between London and Israel, indicative of a dislocation to which I shall return. Gersht, of course, encountered a very different political geography on his parallel journey across the Lister Route, albeit one with residual markers of cultural and historical boundaries, which surface in the challenges facing present-day refugees in the increasingly turbulent political landscape of Europe. The artificial, digitally stitched-together photographic landscapes of Evaders further allude to the idea of political grey areas, and to the arbitrariness of borders, where the landscape becomes representative of process (migration), rather than territory.[70]

The long, linear take on the left of Evaders is located opposite the ‘journey that cannot be attributed to a specific time or place’, an elliptical technique that coexists with aforementioned concepts of expansion.[71] Gersht is attempting to bring an added dimension to his depiction of Benjamin; a contemplative appraisal of his subject, much as a painter might afford their sitter, enabling him to ‘grow into’ the image.[72] A similar motivation lies behind the long, painterly exposures of the journey depicted in White Noise, and the sculpting of Gersht’s subject via light and shadow in the oblique, meditative Will You Dance for Me.

Gersht’s Artist’s Book is further suggestive of such a tendency. Film stills from Andrey Tarkovsky’s Ivan’s Childhood (1962) and Béla Tarr’s Sátántangó (1994) feature as inspiration for Evaders. Tarr’s Sátántangó, a seven-hour-long epic set on a collective farm in communist Hungary, comprising a sequence of anachronous scenes and operating in ‘endurance-length takes’, has been said to borrow much from Tarkovsky’s dream-like, meditative cinema.[73] Tarkovsky likens the making of cinema to ‘sculpting in time’, emphasising film’s significance in enriching collective experience, in the vein of Benjamin, by ‘juxtaposing a person with an environment that is boundless…relating a person to the whole world: that is the meaning of cinema’.[74] While appearing to depart from the rapid flash of the dialectical image, this elliptical, peripatetic approach echoes Benjamin’s concept of a non-linear dialogue between a multitude of ‘images’ and corresponding moments in, or out of, time.

Benjamin travels forward in space along the Lister Route without making any real progress. Gersht is fascinated by the idea that ‘progress goes in circles, failing to form…a direct path to a destination, and returning, inevitably, toward beginnings that are endings’.[75] This study of movement finds its place in Benjamin’s open-ended dialectical method, his asynchronous concept of history in ‘Theses’, and the angel’s involuntary propulsion into the future while remaining transfixed by the ruins of the past. The meandering technique also inhabits the concept of the Romantic journey as inherently incomplete, with ‘deferral as its chief trope’, and refers back to the indeterminacy of art in a post-Holocaust context.[76] Friedrich Schlegel described Romantic poetry as a ‘state of becoming’ rather than a ‘state of being’, while Benjamin considered his Arcades Project to be intentionally incomplete, and open to possibility.[77]

The sublime Romanticism of the Pyrenean landscape in Evaders functions as a visual metaphor for the philosopher’s cultural struggle, with the storm providing pathetic fallacy. There is something of the afterlife in the redemptive purple mists (symbolic of creation in Judaism), or indeed, a kind of purgatory in the sulphuric clouds that rise from the jagged black cliffs (Fig. 7). The heavy suitcase that Gersht’s Benjamin carries is itself suggestive of cultural burden, and of an inability to detach oneself. In fleeing, Benjamin was largely concerned with ensuring that the unknown manuscript would evade confiscation by the Gestapo. The critic shared his conviction with Lisa Fittko that ‘it is more important than I am’.[78]

The complex interplay between nature and culture that informs our reading of landscape and history is crucial to Gersht, for whom the encounter with the landscape constitutes a ‘personal rite of observance’.[79] To Benjamin, nature and culture are treated as indexical – brief, analogous references appear in ‘Theses’. In Gersht’s work, however, and in our present, nature has been subsumed by culture, and by our mark on the land: history bleeds out of his landscapes.

Caspar David Friedrich’s landscapes, themselves fantastical constructs of the imagination, are mirrored in the composite photographs of Evaders, and in the painterly expanses of earlier series such as Liquidation. Friedrich approached landscape as consciousness, reflecting both individual and national identity, and man’s relationship with nature. His landscapes are predominantly read in terms of nationalism and individual heroism. The relevance of this is not lost on Gersht, particularly with reference to Benjamin’s troubled national identity, and his attachment to European culture. This heroism is conveyed through the lone figure with his back turned to the viewer, the Rückenfigur, located in the midst of a monumental German vista, as in the triumphal heights of Friedrich’s Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog (1818). These are often scenes of military victory, imbued with symbolism and allegory – the Wanderer atop Friedrich’s mountainous peak is representative of the deceased patriot in his uniform of the volunteer rangers; the painting functions as an epitaph in its sublime transcendence.[80] Here we return to the concept of redemptive creation, in which Friedrich’s figures transcend death by means of art (as could be said of Benjamin’s ‘Theses’, published posthumously). Similarly, Friedrich’s Chasseur in the Forest (1814) depicts the vanquished figure of a Napoleonic infantryman in a landscape saturated with German patriotism. Such imagery was co-opted in the twentieth century as a means to propagate the nationalist agenda – Göring and Himmler were frequently photographed in sylvan settings, evocative of Tacitus’s Germania.[81] Robert Rowland Smith considers the darker legacy of these Übermenschen:

[They] had attained a peak of human perfection, the roof of the world. But this resulted in war, confusion and displacement … when Gersht summons up such images of transcendence, we are invited to understand them with all the irony of a false dawn, with the knowledge of the tragedies that ensued.[82]

In the right-hand screen of Evaders, the spectral figure’s back is also turned to the viewer, subsumed by the vastness of nature, thus ‘rendering him subtly anonymous, or perhaps universalizing his cause’.[83] An equilibrium is established between the figure’s insignificance and its humanist role in Friedrich’s depiction of ‘the originary act of experience itself…the encounter of subject with world’.[84] The figure mournfully confronts the human condition, and it is in this sense that Gersht employs Benjamin as a symbol of the humane, as counterpoint to the annihilation of the individual and the collective.

Following Benjamin’s death, Klee’s Angelus Novus was bequeathed to Georges Bataille, along with the Arcades Project. It was subsequently passed on to Adorno in New York, ultimately finding its resting place in Jerusalem’s Israel Museum, from where it continues to observe history unfold.[85] Judith Butler draws interesting parallels between Benjamin’s analysis of state violence, typified by the double capacity of the military to enforce and make law in his ‘Critique of Violence’ (1921), and Israel’s history of conduct in the occupied territories.[86] She aims to ‘delineate a political ethics that belongs to the diaspora’, one that specifically locates the relevance of Benjamin’s ‘Theses’ in the plight of the contemporary refugee.[87] The State of Israel invokes self-defence and preservation as key objectives in its conflict with Palestine, indicative of its traumatic history. Butler reinterprets Benjamin’s dialectics at a standstill in her ‘politics of remembrance’, describing a hypothetical break in this cycle of mutual suffering when ‘someone’s memory is interrupting someone else’s march forward…because something of that suffering over there resonates with the one over here, and everything stops’.[88]

Gersht’s ambivalent relationship with his native Israel informs his interest in the plight of the stateless, and a life defined by contested borders. This is explored in his first film, Neither Black nor White (2001), in which he overexposes a time-lapse panorama of a Palestinian community in Israel on loop; the blinding whiteness is suggestive of a bomb detonating. Gersht’s national identity is also alluded to in Big Bang, where the wailing of sirens in Tel Aviv (both to commemorate Holocaust Memorial Day, and as an ‘all-out war siren’) builds intolerably in pitch, and in his interrogation of the nationalist connotations of flowers in his Fragile Land series (2018).[89] The flowers in Fragile Land are suspended in air, bulbs untethered from the earth, evoking the rootless anxiety of the diaspora. Hava Aldouby reads this as a ‘groundlessness’, a precarity that may be countered by the material and the experiential. This has echoes in the aforementioned dance between absence and presence (or indeed, abstraction and figuration) in Gersht’s work, where even a destructive force can create ‘presence’ through reconfiguration, much as destruction can prefigure redemption for Benjamin. In Aldouby’s ‘restorative drive [of] migratory aesthetics’, the restitution of presence is analogous to recuperative grounding.[90] The material presence that may be gleaned from a violent intervention (which symbolically demarcates absence) is expressed perhaps most viscerally in the falling trees of The Forest (2005), filmed in Ukraine, which crash through the silence of amnesia to reinforce the suffering endured by Gersht’s family in that landscape, as a kind of ‘inverted monument’ to genocide.[91]

Daniel Karavan’s monument to Benjamin at Portbou, which surfaces at the end of Evaders, brings us to a closing discussion of more traditional forms of commemoration. Michael Taussig describes the sense of entombment encountered upon entering the dark steel tunnel of Passages (1990–94), which frames a panorama of the coast and sea at its end.[92] Gersht employs the motif of the monument to represent a final passage from life to death, and an encounter outside of time between Benjamin and his contemporary legacy. We observe Gersht’s Benjamin take his final steps through the darkness towards a white portal at the end (Fig. 8). Henry Pickford argues that memorials ‘share critical affinities with Benjamin’s notion of “dialectical images” as the sites of historical materialism and remembrance’.[93] Karavan’s ‘counter-monument’ is dedicated not only to Benjamin, but also to the forgotten and persecuted masses of history, as observed in its inscribed quotation from Benjamin – ‘historical construction is devoted to the memory of the nameless.’[94] As Jeremy Millar suggests, ‘between remembrance and forgetting, there is perhaps a middle ground emerging in the half-light in which some are remembered solely for the fact that they had been forgotten.’[95]

It could be argued that the call for remembrance and awareness established by Karavan’s monument, as with Gersht’s Evaders, situates it beyond associations of impotent mourning or heroic commemoration.[96] But can humanist remembrance, as distinct from organized political action, function in a truly redemptive capacity? The non-prescriptive nature of Gersht’s aesthetic interventions could itself hold the greatest hope of recouping loss, by facilitating active interrogation. The questions that arise from the tension and instability of his process, in the space between absence and presence, and between the universal and the individual, may themselves forestall the erasure of memory and history.

Conclusion

Gersht’s practice is predominantly occupied by ethics. It has no explicit, overtly political imperative, and there is no attempt on the artist’s part to galvanise revolutionary action in the present. Gersht’s is a subtler exercise in conscious remembrance and vigilance. He inhabits the gravity of his role as interlocutor between the dwindling community of Holocaust survivors and his audience with sensitivity and thoughtfulness. His assertion of the humane is an attempt to recoup loss by transcending death and destruction. The elegiac, contemplative nature of his work, while situated far from an ideal emancipatory art in Benjamin’s view, does possess a restorative capability, and functions as salve to soften the blow of trauma, even as Gersht coaxes suffering to the surface. His tendency towards abstraction creates distance, certainly, but he is often working in the realm of the inconceivable.

The radical, if tentative, facet of Benjamin manifests in the indeterminacy of his writing, yet equally, in its wealth of cultural reference and fluidity. His philosophy offers infinite potential for a habitable utopia and an active political life, even while the means to its realisation are tenuous. Gersht employs Benjamin’s aphoristic, asynchronous montage in articulating his own vision of remembrance in film, and in shaping the physical and psychological terrain of his subjects. The artist cultivates a necessary tension that encourages debate, and an openness that urges resistance to determinist or revisionist accounts of history, all the more relevant in a context of resurgent nationalism and troubling amendments to European memory laws, seventy-five years after the liberation of Auschwitz.

The image of the itinerant Benjamin, bearing the burden of his beloved culture like a talisman in the face of its annihilation, illuminates Gersht’s conflicted longing for an ancestral Europe. Despite dealing in specific narratives (an Auschwitz survivor-turned-dancer, a Jewish-German intellectual and refugee) and operating in a relatively narrow sphere of relations between European history and the Jewish diaspora, the individuals that inhabit Gersht’s work are representative of a wider migratory anxiety and yearning for home. Gersht’s Benjamin is thus also an avatar for the nameless, stateless masses, past and present. Evaders re-situates Benjamin’s legacy in Gersht’s collective, contemporary framework and comes close to perpetuating the philosopher’s dialogue in the present with redemptive moments from the past.

Julie Hrischeva is Editor of Art and Architecture at Yale University Press, London. Before moving into academic publishing, she worked as an editor and project manager at Aesthetica and TANK magazines. She completed her MA at The Courtauld Institute of Art in 2014, graduating with distinction from Professor Julian Stallabrass’s Special Option Documentary Reborn: Photography, Film and Video in Global Contemporary Art.

Citations

[1] The circumstances surrounding Benjamin’s death are unclear, and theories challenging the popular account of his suicide proliferate, including that of his assassination by Stalinist agents or by Spanish nationalists colluding with the Gestapo.

[2] Walter Benjamin, ‘Theses on the Philosophy of History’, Illuminations, transl. Harry Zohn, ed. Hannah Arendt (New York: Schocken, 2007), 257–258.

[3] Robert Rowland Smith, Artist Book: Ori Gersht (Brighton: Photoworks, 2012), 11.

[4] Ori Gersht et al., Ori Gersht: History Repeating (Boston: MFA Publications, 2012), 234.

[5] Carol Armstrong, ‘Ori Gersht: The Angel of History’, Eikon, 66 (2009), 26.

[6] Richard Dyer, ‘Towards the Re-Presentation of History: Ori Gersht in conversation with Richard Dyer’, PLUK 28 (January/February 2006), 28.

[7] Liz Wells, Land Matters: Landscape Photography, Culture and Identity (London: I.B. Tauris, 2011), 317.

[8] Al Miner, ‘Ori Gersht: History Repeating’ in Gersht et al., 49.

[9] Hava Aldouby, ‘Courting Absence, Restoring Presence’ in Ori Gersht: History Reflecting (Boston: MFA Publications, 2014), 91.

[10] Hope Kingsley and Christopher Riopelle, Seduced by Art: Photography Past and Present [exhib. cat.] (London and New Haven, CT: National Gallery; Yale University Press, 2012), 80, 179.

[11] Hilarie M. Sheets, ‘Beauty, Tender and Fleeting, Amid History’s Ire’, The New York Times (23 August 2012, accessed: 27 February 2020, http://www.nytimes.com/2012/08/26/arts/design/ori-gersht-history-repeating-at-museum-of-fine-arts-in-boston.html?pagewanted=all&_r=1&).

[12] Sheets.

[13] Armstrong, 26.

[14] Ori Gersht, David Chandler and audience discussion at Hackney Picturehouse screening of the artist’s work (13 February 2014).

[15] See ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’ in Benjamin (2007), 217–252.

[16] Susan Buck-Morss, Dialectics of Seeing: Walter Benjamin and the Arcades Project (Cambridge, MA, and London: MIT Press, 1989), 218.

[17] Benjamin (2007), 255.

[18] Miner, 32.

[19] Ori Gersht discussion (13 February 2014).

[20] Buck-Morss (1989), 250. Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project, transl. Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin, ed. Rolf Tiedemann (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002), 482.

[21] Benjamin (2007), 262; Didi-Huberman 117.

[22] Benjamin (2007), 257; Stéphane Mosès, The Angel of History: Rosenzweig, Benjamin, Scholem, transl. Barbara Harshav (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2009), 121.

[23] Richard Wolin, Walter Benjamin: An Aesthetic of Redemption (Berkeley, CA, and London: University of California Press, 1994), 264.

[24] Miner, 45.

[25] Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, transl. Richard Howard (London: Vintage, 2000), 27.

[26] Ronni Baer, ‘A Conversation with Ori Gersht’ in Gersht et al., 235.

[27] Benjamin (2007), 236.

[28] Ori Gersht discussion (13 February 2014); Barthes, Camera Lucida, 45.

[29] Wells, 308.

[30] Ori Gersht discussion (13 February 2014).

[31] Esther Leslie, ‘The Multiple Identities of Walter Benjamin’, New Left Review, 226 (November–December 1997), 129.

[32] Benjamin (2007), 258.

[33] Michael Taussig, Walter Benjamin’s Grave (Chicago, IL, and London: University of Chicago Press, 2006), 15.

[34] Rolf Tiedemann, ‘Dialectics at a Standstill’ in Benjamin, The Arcades Project, 938. Gershom Scholem, Walter Benjamin: The Story of a Friendship, transl. Harry Zohn. New York: Schocken, 1981), 221.

[35] Scholem wrote of Benjamin’s experiment with materialism. Gershom Scholem, On Jews and Judaism in Crisis (Philadelphia, PA: Paul Dry Books, 2012), 186.

[36] Tiedemann, 945.

[37] The wager, as discussed in Michael Löwy, Fire Alarm: Reading Walter Benjamin’s On the Concept of History (London: Verso, 2005), 11; Judith Butler, Parting Ways: Jewishness and the Critique of Zionism (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012), 107. See also Georges Didi-Huberman, The Eye of History: When Images Take Positions (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2018), 246–247.

[38] Hannah Arendt, ‘Introduction’ in Benjamin (2007), 34, 257. Buck-Morss (1989), 243.

[39] Susan Sontag, Under the Sign of Saturn (New York: Vintage Books, 1981), 111.

[40] Esther Leslie, Walter Benjamin (London: Reaktion, 2007), 218.

[41] Löwy, 10.

[42] Benjamin, The Arcades Project, 365. Buck-Morss (1989), 237.

[43] Theodor W. Adorno, Prisms, transl. Samuel and Shierry Weber (Cambridge, MA, and London: MIT Press, 1997), 233.

[44] Ursula Marx, ed., Walter Benjamin’s Archive: Images, Texts, Signs, transl. Esther Leslie (London: Verso, 2007), 251.

[45] David Chandler, ‘Searching in the Ruins of Memory’ in Ori Gersht: History Reflecting, 69.

[46] Benjamin (2007), 257–258.

[47] Benjamin (2007), 257–258, 264. Buck-Morss (1989), 235.

[48] Buck-Morss (1989), 235.

[49] Benjamin (2007), 234.

[50] Didi-Huberman, 114–115.

[51] Sheets.

[52] I refer here specifically to the beautiful seduction of unknown terror, as developed in Kant’s ‘Critique of Judgement’ (1790) and Schiller’s ‘On the Sublime’ (1802).

[53] Photoworks, Ori Gersht in conversation with David Chandler (2011, accessed: 27 February 2020, http://vimeo.com/23963904).

[54] Benjamin (2007), 221. The films of Luis Buñuel, Sergei Eisenstein, and Dziga Vertov’s ‘Kino Pravda’.

[55] Miriam Bratu Hansen, Cinema and Experience: Siegfried Kracauer, Walter Benjamin, and Theodor W. Adorno (Berkeley, London: University of California Press, 2012), 110.

[56] Didi-Huberman, 217.

[57] Richard Shiff, ‘Digitized Analogies’ in Gumbrecht and Marrinan, (eds), Mapping Benjamin: The Work of Art in the Digital Age (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2003), 70.

[58] Theodor W. Adorno, Aesthetic Theory, transl. Robert Hullot-Kentor, eds Gretel Adorno and Rolf Tiedemann (London: Athlone Press, 1999), 210. Henry W. Pickford, The Sense of Semblance: Philosophical Analyses of Holocaust Art (New York: Fordham University Press, 2013), 11.

[59] Pickford, 7.

[60] Pickford, 117.

[61] Pickford, 10.

[62] Yoav Rinon, ‘Manifest Time: The Art of Ori Gersht’ in Gersht et al., 213.

[63] Julia Weiner, ‘We Have a Responsibility to Hold on to Dark Memories’, The Jewish Chronicle (16 February 2012, accessed: 27 February 2020, http://www.thejc.com/arts/arts-features/63639/we-have-a-responsibility-hold-dark-memories).

[64] Varian Fry, Surrender on Demand (London: Atlantic Books, 1999), 31.

[65] Photoworks, Ori Gersht in conversation with David Chandler.

[66] Scholem, 173.

[67] Photoworks, Ori Gersht in conversation with David Chandler.

[68] Susan Buck-Morss, The Origin of Negative Dialectics: Theodor W. Adorno, Walter Benjamin, and the Frankfurt Institute (London and New York: Macmillan, 1977), 166.

[69] Theodor Adorno, Minima Moralia: Reflections from Damaged Life, transl. Edmund Jephcott (London: Verso, 2010), 135.

[70] Ori Gersht: History Reflecting, 17. See Jessica Dubow on exile and diaspora, ‘The Art Seminar’ in Elkins and Delue, 125.

[71] Miner, 32.

[72] As articulated by the philosopher in ‘A Small History of Photography’ in Walter Benjamin, One Way Street and Other Writings, transl. Edmund Jephcott and Kingsley Shorter (London: New Left Books, 1979), 245.

[73] Jonathan Romney, ‘Out of the Shadows’, The Guardian (24 March 2001, accessed: 27 February 2020, http://www.theguardian.com/film/2001/mar/24/books.guardianreview).

[74] Andrey Tarkovsky, Sculpting in Time: Reflections on the Cinema, transl. Kitty Hunter-Blair (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 1989), 66.

[75] Miner, 34.

[76] Smith, 10.

[77] Jeremy Millar, ‘Speak, You Also’ in Jeremy Millar, Ori Gersht: The Clearing (London: Film and Video Umbrella, 2005), 15. Friedrich Schlegel, Friedrich Schlegel’s Lucinde and the Fragments, transl. Peter Firchow (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1971), 116.

[78] Lisa Fittko, Escape Through the Pyrenees (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2000), 106.

[79] Steven Bode, ‘Tracks in the Forest’ in Millar, 5.

[80] Joseph Leo Koerner, Caspar David Friedrich and the Subject of Landscape (London: Reaktion, 2009), 283.

[81] Simon Schama, Landscape and Memory (London: HarperCollins, 1995), 118.

[82] Smith, 10–11.

[83] Koerner, 211.

[84] Koerner, 193.

[85] John Collins, ‘From Portbou to Palestine and Back’, Social Text, 24.89 (Winter 2006), 76.

[86] Benjamin (1979), 141.

[87] Butler, 99–100.

[88] Butler, 113.

[89] Miner, 36.

[90] Hava Aldouby, ‘Balancing on Shifting Ground: Migratory Aesthetics and Recuperation of Presence in Ori Gersht’s Video Installation On Reflection’, Crossings: Journal of Migration & Culture, 10.2 (2019), 161–181, https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/intellect/cjmc/2019/00000010/00000002/art00001;jsessionid=8skrs3boa226.x-ic-live-03, doi: 10.1386/cjmc_00001_1. [Accessed 8 August 2020]

[91] Dyer, ‘Towards the Re-Presentation of History’, 29.

[92] Taussig, 15.

[93] Pickford, 75.

[94] Taussig, 29.

[95] Millar, 10.

[96] Esther Leslie, Walter Benjamin: Overpowering Conformism (London: Pluto, 2000), 234.