By 1200, the overwhelming majority of English parish churches had been established on sites they were to occupy until the Reformation and beyond, and a raft of papal decretals, episcopal ordinances, and dispute settlements had significantly circumscribed their character.1 Moreover, if documentary evidence for the division of responsibilities for the fabric of the church is lacking before the 1220s, evidence from elsewhere in Europe suggests that by the end of the twelfth century the principle that in default it was the rector’s duty to maintain the chancel while the parish should maintain the tower and nave was gaining acceptance.2 Certainly, it is possible to talk of the parish church in 1200 and distinguish it from other types of church, even if there is a blurring at the margins between secular minsters that continued as small-scale collegiate churches and single-priest parish churches per se.3 One might also add that in the course of the twelfth century many local churches had been conveyed to ecclesiastical proprietors and were no longer held by the founder’s family or local landlord.4 As this had the effect of sharpening distinctions between renders owed to the parish and those owed to the manor, it seems likely that it heightened consciousness of the parish as an entity and a community. The pastoral chaos implied in the story of Stori—an English layman who owned land in Derbyshire under Edward the Confessor and is recorded in Domesday as being able to ‘make himself a church on his land and in his jurisdiction without anyone’s permission, and dispose of his tithe where he wished’—would have been unthinkable one hundred and fifty years later.5

The following paper explores how the parish church of c.1200 differed from its predecessors and seeks to evaluate its architectural repertoire in relation to other types of building. Were the choices exercised as to materials, plans, elevations, and surface detailing conditioned by an appreciation that the parish church called for a certain type of architecture? One that created clear divisions between the area set aside for the priest and that occupied by the laity, for instance, or which sought to shape the architecture to contrive distinctive and recognisable silhouettes? Secondly, on the understanding that the period under review wasn’t so constrained by restrictions on finance and expertise as to make the question irrelevant, did the norms of suitability change in the course of the twelfth century?

Long Sutton (Lincolnshire) is a good starting point, given the survival of a celebrated and unusually-informative charter dated to around 1180. By this, William, son of Ernisius, transferred his church at Sutton together with a site for the new building to Castle Acre Priory, giving them ‘three acres of land in Sutton in the field called Healdefen next the road to build a parish church there. And my wish is that the earlier wooden church in the same vill, in place of which the new church will be built, shall be taken away and the bodies buried in it shall be taken to the new church’.6 This transfer of proprietorship and site—and change of material from wood to stone—lies towards the end of a period which saw masonry parish churches come into being and lay owners transfer ownership to ecclesiastical institutions.7 It is also notable that the charter specifies that burials ‘in the church’ should be transferred to the new site (as might have happened in other contexts, but for which we do not have documentary confirmation).8

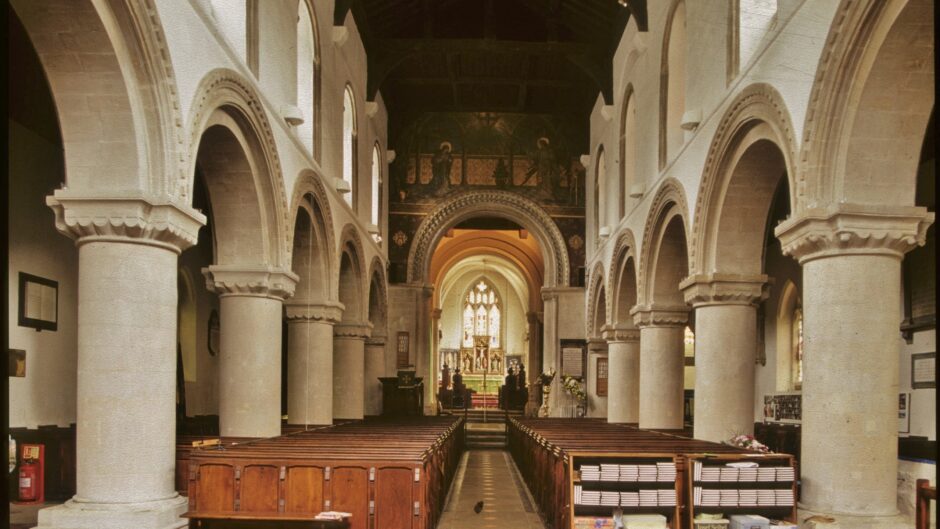

The church which emerged from this—with a seven-bay nave, two-storey elevation, and elaborate arcade—is a good example of a type of parish church that emerged over the second half of the twelfth century (Figs. 1 and 2). It is one that specifically singled out the nave for development, both its arcade and its exterior clerestory, though when Long Sutton was first built on its new site the aisles themselves would have been relatively narrow and dark, hence the subsequent overbuilding of the late-twelfth-century clerestory so as to roof the usual tall and wide late-medieval aisles.9

The date at which Long Sutton was built—the last quarter of the twelfth century—is a date by which an understanding of parishes and their churches had solidified.10 Parochialisation as a process had largely happened by 1180, even if there remained plenty of anomalies, of what might be regarded as leftovers from a minster-based system of pastoral care. At one extreme, there were still superior churches, whether collegiate or not, which administered pastoral care centrally through the thirteenth century. At Beverley Minster, for example, David Palliser has shown how a large parochia was administered from the minster into the late Middle Ages, with four town chapelries and three chapelries outside the town (all with dependent chapel buildings but reliant for baptism and the provision of priests on the Minster).11 Or Pocklington (East Riding, Yorkshire), which to all intents and purposes functioned like an Anglo-Saxon minster without formalised collegiate status: a super-parish with a parochia consisting of ten dependent chapels until 1252, when Archbishop Walter de Gray ordained a vicarage at Pocklington and amalgamated the dependencies into four parishes, though the ultimate supremacy of Pocklington was maintained.12 All but three of those chapels retain evidence of twelfth-century work. Many of them are quite substantial buildings, though none, significantly, is larger than Pocklington.13 Bampton (Oxfordshire) was not dissimilar. Described by John Blair as ‘crypto-collegiate’, Bampton claimed jurisdiction over a large number of chapels and in addition to a rector enjoyed the services of three beneficed clergy, variously described as a ‘prebend-farmer’ and two ‘prebend-portioners’.14 Yet another variation is the post-Conquest prebendal church where more than one parish was served from a single principal building—a twin-rector, twin-parish church—as was the case at Grantham (Lincolnshire).15 William Rufus had granted the churches of Grantham to Osmund, bishop of Sarum, in 1092 and Bishop Jocelyn turned these into two prebends around 1150: Grantham Australis (with dependent chapels at Gonerby, Harlaxton, Cotsworth, Stoke, and Welby) and Grantham Borealis.16 Each prebend held a respective rectory and appointed a vicar, though the two parishes shared a single church—St. Wulfram—a church that, as it happens, was rebuilt from a probably late-eleventh-century core around 1200 and given a vast new elongated late-twelfth-century chancel of a sort encountered below.17 The period between the Conquest and c.1160 does seem to have been one in which the institutional and architectural status of churches was particularly mutable.18

Given these variables, the extent to which status, ownership or history is embodied in the architecture of parish churches by 1200 isn’t easy to assess, though the question merits a different answer to what one might say of the situation at the beginning of the twelfth century. Then, at least as far as we can judge, the wealthiest post-Conquest parish churches were former minster churches that re-emerged as parish churches (rather than as monastic or Augustinian re-foundations of minsters), and churches established by bishops on their manors.19 Sometimes these overlap, as at East Meon (Hampshire), but good examples of the former would be the churches at Shifnal (Shropshire) or Castor (Northamptonshire) and good examples of the latter would be North Newbald (East Riding, Yorkshire), or the church that Roger of Sarum or his successor established in the new town of Devizes (Wiltshire).20

All of the above were initially built or reconstructed as aisleless cruciform churches. It is a form that frequently leaves ghosts or residues when it comes to later medieval development. Take Bampton (Fig. 3). This clearly shows signs of its twelfth-century configuration as an aisleless cruciform church. The exterior silhouette remains strikingly cruciform, while on the interior it is evident that the crossing tower stair turret was an external feature, and that the later medieval transformation began with the construction of a vestry off the north side of the chancel c.1200.21

Needless to say, looking at parish churches from a plan-form perspective—with aisleless cruciform churches at the top of the pecking order—has its limitations. In part this is because we don’t have a sensitive grasp of the nuances of parish church design, of what meanings, if any, may be associated with linear plans nor, more importantly, as to the speed with which such meanings may have been diluted. There are also concrete objections. The rebuilding of former minsters to cruciform plans was not invariable.22 The church at Ledbury (Herefordshire) had minster status before the Conquest but was incorporated into a fluidly-developing parochial system at some point thereafter and was reconstructed to a two-cell design with a partly-aisled chancel.23 Bibury (Gloucestershire) shows no evidence of having been through a cruciform phase, though Bibury was an important Anglo-Saxon minster.24 Norham (Northumberland) is a particularly grand example of a twelfth-century parish church in an episcopal town that didn’t conform to a cruciform plan.25 Turning the relationship around, parish churches with no evidence of minster status could be built to aisleless cruciform designs, as with the ambitious de Braose financed parish church at Old Shoreham (Sussex).26 The plan was also widely endorsed by smaller-scale collegiate churches and, most conspicuously, was used in early Augustinian and Cistercian churches.27 Nonetheless some level of prestige does seem to have been attached to the aisleless cruciform plan that could be endorsed by high-status post-Conquest parish churches. The question is: when does this start to break down? It may be significant that Ledbury’s impressive part-aisled chancel, and the surviving south nave arcade and chancel at Norham, are works of the third quarter of the twelfth century. John Blair’s date of 1160 as the high-water mark of the cruciform plan surely puts this a little late.28 Among grander parish churches, the alternatives were proliferating by then, and the most important of the new alternatives involved aisles; aisles and what goes with them, namely arcades (obligatory) and clerestories (optional). However, before moving on to consider aisles it would be as well to examine another desideratum that had already made an appearance in the eleventh century: the parish church tower.

Towers in aisleless cruciform churches are sited over the crossing, as long as there is a four-arched crossing, which is to say in the overwhelming majority of cases.29 As this is immediately west of the chancel, it is questionable whether the tower belongs with the lay or the rector’s portion of the church.30 Towers attached to the west end of the church are unambiguously associated with the nave, though it does not follow that their introduction was a lay initiative. David Stocker and Paul Everson have argued that the proliferation of west towers in Lincolnshire between c.1075 and c.1125 was ‘an expression of the new doctrinal order’, one that reflected the introduction of ‘the new, dramatic, symbolic liturgy of the reforming Roman papacy’ to the parish church.31 They claim that Bishop Remigius instituted a new form of burial service at Lincoln Cathedral that laid emphasis on a liturgical performance and vigil over the deceased body prior to burial, as Archbishop Lanfranc had done before him at Canterbury.32 This was to take place in a separate space adjacent to the cemetery and was accompanied by the ringing of bells.33 The result, they argue, was the addition of western bell-towers to a large number of pre-existing churches over a period of around fifty years. All of these have an upper bell-stage and can be entered from the nave, while virtually all have, or had, a west portal (Fig. 4).34

There is no denying that the sixty towers identified by Stocker and Everson are sufficiently consistent to be considered a group, nor that they are post-Conquest in date and were built over two or three generations at most. Their social and economic context is notably varied, with around a third of the sample attached to churches built on public open spaces, and therefore likely to have been financed by groups of parishioners and local sokemen.35 Others may have been built at the expense of the manorial tenant. Their distribution is also remarkable, consisting of local clusters with very few outliers. The overwhelming majority are in Lincoln and the north of the county, with a small group in the south-east.36

This regional, or sub-regional, quality to the distribution of parish church towers in Lincolnshire can be found elsewhere. In the diocese of Exeter, for example, there are a significant number of churches with towers attached to their north or south sides.37 They are scattered throughout Cornwall, but in Devon they are overwhelmingly concentrated in the north.38 In East Anglia, a majority of eleventh- and twelfth-century parish church towers are attached to the west end of the nave, but differ from those of Lincolnshire in being round and having no external entry.39 Most are in Norfolk, and even there, there are far more in the east than in the west of the county, with a notable concentration in the Waveney valley. The buildings of England estimated there is evidence for one hundred and forty round towers attached to the west end of parish churches in Norfolk, forty-two in Suffolk, and thirteen in Cambridgeshire and Essex combined.40 The Round Tower Churches Society confine themselves to surviving examples and use post-1974 county boundaries, but they list one hundred and twenty-six in Norfolk, forty-two in Suffolk, six in Essex and two in Cambridgeshire.41 A cogent and detailed argument has been advanced by Stephen Heywood to date the East-Anglian round towers to between c.1070 and c.1200 and relate them to broader patterns of building around the North Sea.42 This seems reasonable, as does the assertion that the peculiar mixing of Norman geometric ornament with so-called ‘Overlap’ forms is so ubiquitous that it might be regarded as ‘an autonomous cultural signature for the region’.43 However, although studies of the East-Anglian round towers examine their form, date, position, and the materials from which they are built, none address how they were used. Unlike the Lincolnshire towers, East Anglia’s round towers lack west portals and can only be accessed from the nave. Thus, if one accepts the argument that the Lincolnshire towers are organised so as to facilitate the procession of the corpse directly to the cemetery, the East-Anglian towers either have nothing to do with funerals, or the burial rite, as presumably introduced to the diocese of Norwich along with the customs of Fécamp by Bishop Herbert de Losinga, was in practice different to that prescribed by Lanfranc for Canterbury.44 If form and function were related, and it is the positioning of portals and, by extension, processional use that is at issue, there must have been significant variations in regional practice.

There are other examples of regional groupings of parish church towers, though these are less concentrated that those of Norfolk or Lincolnshire. In the East Riding of Yorkshire, square west towers seem preferred. In the south midlands there are a significant number of parish churches without transepts but with a tower bay between the chancel and nave, as at Iffley (Oxfordshire) or Stewkley (Buckinghamshire) (Fig. 5). In the decades to either side of 1200, the Fens witnessed substantial investment in the construction of freestanding bell towers.45 The one constant is that parish church towers carried bells. But even here a tower was not a sine qua non. A bell-cote would suffice, even in such expensively finished parish churches as Kilpeck (Herefordshire).

Aisles are less susceptible to regional variation. The date at which these first appear in parish churches is unclear. There are numerous examples of narrow aisles known from excavation, though they are notoriously difficult to date unless there is evidence of the corresponding arcade. In most cases the suppressed aisle walls have been reduced to footings and, as their recovery is usually the result of nineteenth-century restoration, they tend to be poorly recorded.46 Standing examples suggest aisles become popular from around 1140, though there are a handful of earlier examples. There is, for instance, a group of three churches in Buckinghamshire and Hertfordshire whose institutional status at the time their naves were aisled is uncertain, but whose arcades appear eleventh-century. These include Wing (Buckinghamshire), St. Albans (Hertfordshire) and Walkern (Hertfordshire).47 All are pre-Conquest foundations and retain elements of Anglo-Saxon fabric. At St. Albans and Walkern these are single aisles. At Wing, aisles were added to both sides of the nave. If they were parish churches at the time aisles were added, then aisles were a feature of English parish churches before the Conquest. Otherwise, the parish church at Ickleton (Cambridgeshire) is probably the earliest standing example of an aisled English medieval parish church, dating from the last quarter of the eleventh century.48 Ickleton formed part of the honour of Boulogne when the church was constructed, eventually passing via Eustace III of Boulogne’s daughter, Maud, to King Stephen, so it’s reasonable to assume high-level patronage.49 But although the status and wealth of the patron may have facilitated the building, they don’t explain it, and if the counts of Boulogne had intended the church at Ickleton to do no more than serve the parish it would seem to have been exceptional.

By 1140–50, there is no mistaking the popularity of aisles. Former minster churches might be rebuilt on cruciform plans with integral nave aisles, witness Hemel Hempstead (Hertfordshire) (Fig. 6).50 And there is a particular type of clerestory, designed on the half-beat and sunk into the spandrels of the nave arcade, that may have parochial associations. It is popular in the west midlands, as at Clun (Shropshire), and is the form used in the nave at Ewenny Priory, where a wooden roofed nave with a single north aisle was juxtaposed with a vaulted chancel and transepts (Fig. 7). Since there were parochial rights over Ewenny’s nave, the design highlights the different uses to which the two parts of the church were put.51 It is even possible this was a contrast in the service of architectural decorum, deliberated and understood in terms of acoustics and lighting, at least at Ewenny. Otherwise, the syncopated clerestory seems confined to west midlands parish churches. Ripple (Worcestershire) is a thirteenth-century example of the design type.

Though there are other desiderata—as with the towers discussed above—the aisle seems to be the critical area of development in the late-twelfth-century parish church. With aisles and lateral arcades, the highly-articulated longitudinal sequencing of space that characterises most late-eleventh- and early-twelfth-century parish churches starts to dissolve. Romanesque parish churches are almost by definition cellular. They consist of discrete spatial compartments in which the chancel is separated from the nave by an arch, or intermediate bay.52 In most cases these are staggered, so the chancel is narrower than the nave. Where roof lines survive, chancels or apses are invariably lower than naves and are frequently vaulted. Kilpeck (Herefordshire) is a nice example (Fig. 8), or Kempley (Gloucestershire).53 Lesser churches and chapels continued to be built to aisleless linear designs through the second half of the twelfth century. Indeed, there are instances of former minsters being rebuilt to relatively large two or three-cell linear plans as late as c.1180, like Blockley (Gloucestershire).54 However, the half century between c.1130 and c.1180 saw a move away from the simple and the smaller-scale, and it is notable that the generation of parish churches that invests in aisles, like Hemel Hempstead, coincides with the generation that invests in large unvaulted chancels. Among early examples of the latter are at Cliffe (Kent) and Norham (Northumberland), both with aisled naves and twelve-metre aisleless chancels, and both likely built between c.1150 and c.1170 (Fig. 9).55

Our first intimation that the parish church was not necessarily cellular comes at a similar date—around 1140–50, to judge by the style of the sculpture—in St. Peter’s at Northampton.56 This is the earliest example known to me of an aisled parish church without structural division. The church originally consisted of nine bays, with a rectangular east end that projects beyond the aisles (rebuilt in 1850–51) and an axial west tower that cut into the westernmost bay of the nave when it was reconstructed in the seventeenth century. The aisles were refenestrated in the late Middle Ages, though the clerestory remains substantially as originally built. Scott’s restoration respected the twelfth-century forms, reusing many of the original exterior clerestory capitals and corbels.57 Notwithstanding slight variations in the distance between windows, this clerestory takes the form of a continuous arcade on the exterior, while the internal openings are cleverly arranged to both play against the rhythm of the arcade bays and maintain the autonomy of the clerestory (Figs. 10 and 11). In other words, there is an aesthetic dimension to St. Peter’s, a concern to create a correspondence of parts that draws on an established Romanesque tradition of grouping supporting elements in twos and threes and integrating these with the elevation. It is an aesthetic hitherto unexplored in the English medieval parish church, precisely because it requires arcades and multi-storey elevations and prior to c.1140 these were largely confined to Anglo-Norman great churches.58 Needless to say, the level of architectural detailing at St. Peter’s is outstanding and is lavished across tower, nave, and chancel alike. Many of the columns are three-part monoliths with moulded annulets, the arcade voussoirs mix limestone with ironstone, and the capitals are the work of one of the most distinguished groups of sculptors active in the midlands during the twelfth century.59 Even the arch that leads into the tower is like a chancel arch, displaced and exiled westwards. This not only points to high-level patronage, it also points to the involvement of an architect with previous experience of the recondite world of Anglo-Norman pier design.60

Despite the emphasis on open vistas at Northampton, the internal divisions are easy to read. The nave consists of three double bays, outlined by half-columns that rise to the top of the wall from quatrilobe piers (which in turn alternate with columns). The chancel is marked by three bays supported on columns and an absence of vertical articulation.61 Whether the chancel and nave were originally separated by a timber screen is unknown.62 There is no evidence either way. But if not, the subtle guidance provided by the elevation will have been reinforced by orientation and liturgical furnishing alone, for the steps that now lead into the chancel are post-medieval and the nave pavement has been lowered. The mid-twelfth-century floor was level throughout.

Quite what is driving this—why a hall-like building was created for St. Peter’s at Northampton—remains an unanswered question. The church was unquestionably of high status. It was the successor to a minster known to have had a large parochia before the Conquest, with an advowson that swung between the Cluniac priory of St. Andrew at Northampton (founded by Simon I of Senlis, Earl of Northampton) and the king in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries.63 It was also built immediately to the west of what may have been a Mercian royal palace.64 However, despite the pointers to elite patronage and an understandable tendency to ascribe the church to the second earl of Northampton, Simon II de Senlis (d. 1153), neither the immediate circumstances of its construction nor the intentions of its patron are known. Nor have its architectural sources been satisfactorily explained. It is unlike an antique basilica in that there is a western tower and the apse has been squared off. It is unlike a secular hall in that the aisles are low and there is a clerestory. It may be like a monastic building, or hospital, but none survive from the eleventh or early-twelfth century in this particular format.

Northampton has many of the features one associates with the most precocious late-twelfth-century parish churches—particularly those in the Fens—with a clerestory, varied pier designs, a long nave, and sculptural enrichment. Tilney All Saints (Norfolk) of perhaps 1180–90 comes closest, and like Northampton it dispenses with a chancel arch in favour of uninterrupted rooflines and continuous volumes (Fig. 12).65 Tilney also has the virtue of retaining evidence for the original arrangement of windows at the east end of the chancel. Where the central vessel projected beyond the ends of the aisles, the clerestory continued and was joined by two additional windows at the level of the arcade (Fig. 13).66 The arrangement compares with that found in East-Anglian Perpendicular churches such as Blythburgh or Southwold (both Suffolk), and as with these ensured that the eastern projection was the most brightly-lit area within the church.

However, in assessing the origins of the aisled parish church without structural division we may be missing a step. If one subtracts the bell tower, the prototype for at least one type of Fenland parish church, the type which retains a chancel arch, seems to be the monastic infirmary. The relationship is clearest at Walsoken (Norfolk), built in perhaps the 1170s with an aisled chancel, seven-bay nave, columnar and octagonal piers which alternate both along and across the nave, and a stupendous arch marking the chancel entry (Fig. 14).67 The original twelfth-century clerestory even survives in the chancel, albeit now blocked. It relates directly to the new monastic infirmary at Ely, for which there is a terminus ante quem of 1169 thanks to Nicholas Karn’s publication of an episcopal charter granting the monks timber for work on their infirmary (Fig. 15).68 Walsoken even quotes the Ely sanctuary piers (Figs. 16 and 17). This relationship between the late-twelfth-century parish church and monastic infirmaries is one that merits further exploration. Current understanding is that there was a boom in English monastic infirmary construction over the 1150s and 1160s, and that the linear three-part monastic infirmary, with a two-storey aisled hall, chapel, and sanctuary was a new building type, one that displaced earlier cloister or courtyard-based monastic infirmaries.69 However, there may have been examples of in-line hall-chapel infirmaries before the middle of the century. The infirmary built at St. Albans by Abbot Geoffrey de Gorron (1119–46) was described as an aula ‘cum capella versus orientem’ and may have been influential.70 Hospitals and monastic guesthouses may similarly have been built as aisled halls with eastern chapels in the second half of the twelfth century, though the evidence is poor and points in too many directions to suggest there was a preference for any one plan type.71

Notwithstanding the origins of the building type, the reason for labouring Northampton, Tilney All Saints, and Walsoken—and one can extend this to Long Sutton—is that despite differences in their treatment of the relationship between chancel and nave, all four can be described in ways one might describe thirteenth- and fourteenth-century parish churches. They are over thirty metres long, with relatively thin walls, slender piers, aisles, two-storey elevations, and wooden roofs. Their nave arcades are perfectly adaptable and simply served as a platform for new clerestories and roofs. The difference between the parish church in 1200 and the same in 1400 strikes home when one looks at their exteriors, and is largely down to the status accorded to the aisles and the size of the windows.72

These two features—that is, aisles and large windows—are, I believe, unrelated. At least, they don’t arrive together. Large windows are a rare feature in twelfth-century parish churches. The surviving Romanesque window opening at, say, Thornham Parva (Suffolk) is reasonably representative of a twelfth-century parish church window (Figs. 18 and 19).73 And on the few occasions when large Romanesque windows survive they are invariably applied to aisleless spaces. The surviving examples at Iffley (Oxfordshire) or Stewkley (Buckinghamshire) are about as big as they come (Fig. 5).74 The stunning aisleless chancel at Cliffe (Kent) would be another example. One certainly never finds original large window openings in twelfth-century parish church aisles. Romanesque parish church aisle windows are always small, as in the case of Compton (Surrey).75 They are also low-set, because the aisles are low; so low, in fact, that where original aisle walls are retained from pre-thirteenth-century arrangements the aisles are frequently heightened. Compton rather nicely captures the difference, where the south aisle was heightened but the north was not (Fig. 20). The classic demonstration of this is the development of Castor (Soke of Peterborough) from a post-Conquest aisleless cruciform church (Fig. 21).76 When the nave was aisled, probably around 1220–30, the upper nave wall was retained, but it was necessary to take out the lower masonry and cut through the twelfth-century transept west window, leaving a trace of the earlier roof line. By the fourteenth century, the desire for tall traceried windows was irresistible and the aisle was heightened.

So common was the practice of expanding aisles that exceptionally few late-twelfth- or early-thirteenth-century aisles survive in their original state as simple lean-tos with low parapets. Where they do, as at Little Faringdon (Oxfordshire), they tend to be narrow, though it’s clear that not all were (Fig. 22).77 The important parish church at Redbourn (Hertfordshire) was rebuilt in the middle of the twelfth century with wide aisles, which retain a characteristically low-set Romanesque window head.78 Width is much less of an issue than height.

So, what motivates the proliferation of aisles in English parish churches from around 1140 onwards? When looking into this question, scholars tend to return to the same potential wellsprings: altars, burials, chantries, population growth, great church envy, architectural grandeur.79 Population growth must have been a factor, although a related phenomenon—the increased use of parish churches by parishioners for purposes other than attendance at the Mass—may also have been significant. In a case study based on parish churches in Warwickshire, Lindsay Proudfoot drew attention to a correlation between ‘the pattern of nave and aisle extension in parish churches and known national and regional population trends’.80 The greatest growth in the combined floor area provided by nave and aisles took place between c.1250 and c.1340, when parochial (non-chancel) floor space increased by 48.6 percent.81 The increase between c.1200 and c.1250 was 8.7 percent. The appearance of aisles in parish churches from c.1140 onwards may therefore have been an early, and initially limited, response to the upswing in population. By c.1250, when a new type of aisle had been developed—one that was both taller and wider than twelfth-century aisles—it was easier to effect significant relative expansion in floor area. It may also reflect the hardening-up of the parochial map. Far fewer new parish churches were created between 1250 and 1340 than had been created in the twelfth century, so increased populations had to be accommodated in existing churches.

There obviously is a practical advantage to the addition of aisles, though there are significant qualifications to the statistical method.82 Differences of spatial provision in churches in adjoining parishes of comparable size and economic potential imply there will be examples of both the over- and under-provision of space. And surplus wealth in the hands of individual parishioners, if channelled into the parish church, could lead to the large-scale expansion of a church, regardless of population size. There are examples of this in the later Middle Ages.83 It may similarly have been a feature of the largely undocumented addition of aisles to parish churches in the decades around 1200.

In addition to the simple provision of space, aisles accommodated a variety of functions by the fourteenth century. Were these considerations in the adoption of aisles in parish churches in the second half of the twelfth century? Chantries one can rule out, at least as an instigator of the fashion. Chantries were often established in aisles in the later Middle Ages, but aisles come into being before there is evidence for chantries in parish churches, which on existing knowledge is around 1200.84 As for burials, their impact is arguably best understood from Warwick Rodwell’s excavations of St. Peter’s at Barton-upon-Humber (Lincolnshire). These encompassed the most comprehensive examination of parish church burials ever undertaken in England and enable one to compare the incidence and location of burials between the tenth and nineteenth centuries on a century-by-century basis.85 If one examines the situation with regard to the addition of narrow aisles over the later twelfth and thirteenth centuries, there is a small group of burials in the first south nave aisle, but in comparison to the situation prior to the creation of the nave aisles it is hardly a step change.86 As Rodwell remarks, ‘the incidence of indoor burial was low before the mid-thirteenth century’.87 The later thirteenth-century widening of the south nave aisle resulted in many more south aisle burials than was prompted by the initial twelfth-century expansion. This suggests that burials certainly colonised aisles once they had been built, but that before the later thirteenth century the overall number of burials within the church remained roughly constant, with or without aisles.

Altars are more promising, and aisles are often equipped with them. It is clear that at Little Faringdon, there was an altar with accompanying piscina at the east end of the north aisle, where a vestry door was subsequently inserted (Fig. 23). It is equally clear that there was not an altar at the east end of the south aisle at Castor.88 Aisles will certainly provide an altar emplacement that faces in the same direction as the chancel altar and doesn’t hinder movement by sitting west of the chancel arch, though technically there is no reason why an altar could not have been set against an aisleless nave wall.

Among formal, allusive, and symbolic criteria, great church emulation is, I think, a non-starter. Notwithstanding such oddities as New Shoreham or Hythe with their three-storey chancels, one mostly searches in vain for late-twelfth- or early-thirteenth-century vaulted nave aisles.89 Parish church builders, or lay parishioners, do not seem to have been looking at great church aisles, or great church elevations for that matter. Indeed, the dialogue with great church architecture exists at a wholly different level of detail, and is seen in moulding profiles, pier designs, and sculptural embellishment. The c.1200 nave piers at Grantham are variations on Lincoln Cathedral designs. Its section or elevation emphatically is not.90 The same can be said for many early-thirteenth-century parish churches in Nottinghamshire.91

Symbolic explanations, along with considerations of changes in liturgical practice, tend to founder on particularism, or the lack of it. There are both too many and too few parish churches that had adopted aisles by the first quarter of the thirteenth century for them to be the result of multiple individual patronal desires to create a church as an image of some other paradigm—like the Constantinian basilica—or a universal perception that a church without aisles was metaphysically deficient.

Finally, looked at from a formal and visual perspective, what is striking is not the aisle as seen from the aisle, but the aisle as seen from the nave. Aisles introduce arcades, and arcades introduce a level of architectural complexity. There may have been many reasons behind the burgeoning popularity of aisles in the run-up to 1200, but their capacity to reformulate an elevation by delivering an architecturally-distinguished backdrop must count high among them. One sees any number of examples of this: Kelmscott (Oxfordshire), Little Faringdon (Oxfordshire), the north nave arcade of St. Mary at Barton-upon-Humber (Lincolnshire), St.-Nicholas-at-Wade (Kent) (Fig. 24).92 As an approach to architectural renewal, a new aisle lies between refenestration and the significantly greater expense that would be involved in the complete replacement of the nave, but can still achieve a lot in visual and spatial terms.

None of the considerations aired above is exclusive, and it is highly unlikely that there was a single overriding reason behind the introduction of aisles. That may seem an unsatisfactory conclusion, but in the context of ecclesiastical architecture more generally it is hardly surprising. From as early as the fourth century one can see different functions allotted to aisles: the separation of the sexes; the provision of processional routes, particularly in funerary contexts; the enhancement of the central vessel with an arcaded frame, in turn enriched with or without textile hangings. Though the uses change over time, aisles never seem to have been reduced to a single primary purpose.

The aim of this paper was to evaluate the architectural repertoire of the parish church in 1200, particularly in relation to other types of building, and the evidence suggests that, by the end, a distance from the great church had opened. In part this was by default. The parish church espoused forms that great churches had left behind. Clerical communities no longer entertained aisleless and multi-cellular churches, while once prestigious forms—such as axial western towers—became the sole preserve of the parish.93 More radically, the adoption of aisles brought new permutations into play. That this was an independent initiative is clear from the types of aisles that were introduced—lightweight, wooden-roofed, lean-to structures with low outer walls-aisles—which cannot be understood on great church terms. It is easy to overlook this last point, since it is rare for the outer walls of aisles to survive in their twelfth-century state. Their external elevations, the architectural potential of the aisle, was only realised in the thirteenth century with the arrival of tall windows. The status accorded to the aisle is the crucial difference between the parish church in 1200 and its late-medieval offspring. Nonetheless, as aisles brought a new spatial definition to the nave in the middle decades of the twelfth century, so a possible avenue for architectural development was opened, an avenue that seems to have been most enthusiastically explored in eastern England. With thin walls, slender piers, two-storey elevations, and wooden roofs, the late-twelfth-century churches of the economically-vibrant Fens might be regarded as the late-medieval parish church in embryo.

Citations

[1] See, inter alia, the various contributions in John Blair (ed.), Minsters and Parish Churches: The Local Church in Transition 950–1200 (Oxford: Oxford University Committee for Archaeology, 1988); John Blair and Carol Pyrah (eds.), Church Archaeology: Research Directions for the Future (York: Council for British Archaeology, 1996), especially pp. 1–18; Susan Wood, The Proprietary Church in the Medieval West (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006); Richard Morris, Churches in the Landscape (London: J.M. Dent, 1989), especially chapters 5–7.

[2] See Frederick Maurice Powicke and Christopher Robert Cheney (eds.), Councils and Synods and Other Documents Relating to the English Church, Vol. II, part I (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1964), p. 128, for Bishop Peter des Roches’s 1224 statutes governing chancel repair in the diocese of Winchester. For the continent, Michel Parisse cites a late-twelfth-century dispute regarding parish churches dependent on the priory of Saint-Vincent at Chaligny in the diocese of Toul. The bishop found that the restoration of the chancel was the responsibility of the parish priest, while the tower belonged to the parishioners. Cancelli restauratio sub cura sacerdotis erit. Turris vero ad parrochianos pertineat. Michel Parisse, ‘Recherches sur les paroisses du diocese de Toul au XIIe siècle : l’église paroissale et son desservant’, in Le instituzione ecclesiastiche della ‘Societas Christiana’ dei secoli XI e XII : diocesi, pieve e parrochie (Milan: Miscellanea del centro di studi medioevali, 8, 1977), p. 567. See, most recently, Carol Davidson Cragoe, ‘The Custom of the English Church: Parish Church Maintenance Before 1300’, Journal of Medieval History 36 (2010): pp. 20–38, especially pp. 29–30.

[3] John Blair, ‘Clerical Communities and Parochial Space: The Planning of Urban Mother Churches in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries’, in T. R. Slater and Gervase Rosser (eds.), The Church in the Medieval Town (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1998), pp. 272–94.

[4] For an account of the process of the alienation of advowsons and the ownership of parish churches see George William Outram Addleshaw, The Development of the Parochial System (London: St. Anthony’s Press, 1954) and Rectors, Vicars and Patrons in Twelfth- and early Thirteenth-Century Canon Law (London: St. Anthony’s Press, 1956). Both studies were conveniently reprinted as paperback pamphlets by the Ecclesiological Society in 1986 and 1987 respectively.

[5] Domesday Book, I, 280b. See Philip Morgan, Susan Wood, and John Morris (eds.), Domesday Book. 27, Derbyshire (Chichester 1978), 280b at 16. Quoted in Wood, Proprietary Church, p. 598.

[6] London, British Library, MS Harley 2110, folio 70v. Dorothy Owen dates the conveyance to ‘before 1180’. Dorothy Owen, Church and Society in Medieval Lincolnshire (Lincoln: Society for Lincolnshire History and Archaeology, 1990), p. 5.

[7] Richard Morris identifies the eleventh and twelfth centuries as the ‘one period during which the construction of [churches] in stone was practiced as a general national activity’, and although the numbers of new buildings and precise chronology will have varied across the country there is no doubt that the incidence of new churches went into sharp decline throughout England after 1200. Richard K. Morris, ‘Churches in York and its Hinterland: Building Patterns and Stone Sources in the 11th and 12th Centuries’, in Blair (ed.), Minsters and Parish Churches, p. 191.

[8] See, for example, the suite of three tombs in the north chancel aisle of the late-thirteenth-century church at Winchelsea (Sussex), which possibly commemorates members of a family originally buried in the church on its earlier site.

[9] Both the chancel arch and the pilaster buttresses at the west end of the nave form part of the late-twelfth-century church, though the chancel arch was heightened in the fourteenth century to accommodate the new clerestory and extended chancel. Nikolaus Pevsner, John Harris, and Nicholas Antram, Lincolnshire, second edition (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1989), pp. 534–6.

[10] John Blair describes the period between the Conquest and the 1150s as ‘the incubation period of the modern parochial system’. John Blair, ‘Introduction: From Minster to Parish Church’, in Blair (ed.), Minsters and Parish Churches, p. 10.

[11] David Palliser, ‘The “Minster Hypothesis”: A Case Study’, Early Medieval Europe 5 (1996): pp. 211–14. The late survival of this type of superior church with a large parochia and lots of chapelries seems to have been particularly common in Yorkshire. See also Aleksandra McClain, ‘Patronage in Transition: Lordship, Churches, and Funerary Monuments in Anglo-Norman England’, in J. Sánchez-Pardo and M. Shapland (eds.), Churches and Social Power in Early Medieval Europe (Turnhout: Brepols, 2015), pp. 185–225.

[12] James Raine (ed.), The Register, or Rolls, of Walter Gray (York: Surtees Society 56, 1872), pp. 211–13.

[13] The chapels are at Fangfoss, Yapham, Great Givendale, Millington, Barmby Moor, Allerthorpe, Thornton, Bielby, Hayton, and Burnby. Barmby Moor and Allerthorpe were completely rebuilt in the nineteenth century. Of the others only Thornton does not retain any stonework which predates 1200. Discussed in Richard Morris, Churches in the Landscape (London: Orion Books, 1997), pp. 135–6.

[14] Blair, ‘Clerical Communities and Parochial Space’, pp. 275–6; A. P. Baggs et al (eds.), Victoria County History: Oxfordshire; Vol. 13 (Oxford: Institute of Historical Research, 1996), pp. 48–53. In 1220 the prebends were transformed into three perpetual vicarages served by resident vicars.

[15] Parish churches with more than one rector are usually constituted as a single parish and are either former minsters, like Bampton, or are the result of a division of lay dominium over a church between co-heirs. See Addleshaw, Rectors, Vicars and Patrons, p. 11.

[16] D. Greenaway (ed.), Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1066–1300: Volume 4 Salisbury (London, 1991), accessed 1 June 2021, https://www.british-history.ac.uk/fasti-ecclesiae/1066-1300/vol4. Grantham Australis is listed at pp. 68–70 and Grantham Borealis at pp. 70–2.

[17] Philip Dixon, ‘The Church of St Wulfram 1: The Development of the Church’, in David Start and David Stocker (eds.), The Making of Grantham: The Medieval Town (Heckington: Heritage Trust of Lincolnshire, 2011), pp. 51–70; and John McNeill, ‘The Church of St Wulfram 3: Architecture, Patronage and Context’, in Start and Stocker (eds.), The Making of Grantham, pp. 95–108. See especially the plan at figure 25 on p. 58.

[18] A celebrated example at local church level is Shobdon (Herefordshire). Here, Oliver de Merlimond replaced a wooden chapel subject to the neighbouring parish church at Aymestry with a masonry church, having arranged for Shobdon’s independence on payment of an annual pension. With the help of the local bishop, Oliver then upgraded his church to a Victorine priory by recruiting two canons from the abbey of Saint-Victor in Paris, before a dispute led to the eventual removal of the Victorine abbey to Wigmore and the settling of simple parochial status on the church at Shobdon: a status it continues to enjoy. For a full account see John C. Dickinson and Peter T. Ricketts (eds.), ‘The Anglo-Norman Chronicle of Wigmore Abbey’, Transactions of the Woolhope Naturalists’ Field Club 39 (1967–69): pp. 413–45.

[19] Blair, ‘Clerical Communities and Parochial Space’, passim; Malcolm Thurby, ‘Minor Cruciform Churches in Norman England and Wales’, Anglo-Norman Studies XXIV (2002): pp. 239–76. Clear associations between ‘old minster’ churches and twelfth-century reconstructions on aisleless cruciform plans in the diocese of Canterbury are discussed in Tim Tatton-Brown, ‘The Churches of Canterbury Diocese in the Eleventh Century’, in Blair (ed.), Minsters and Parish Churches, pp. 109–11.

[20] For East Meon see William Page (ed.), Victoria County History: Hampshire; Vol. 3 (London: Archibald Constable, 1908), pp. 64–75; for Shifnal see John Newman and Nikolaus Pevsner, Shropshire (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006), pp. 502–5. For North Newbald see John Bilson, ‘Newbald Church’, Yorkshire Archaeological Journal 21 (1911): pp. 1–42; for Devizes see Roger Stalley, ‘A Twelfth-Century Patron of Architecture’, Journal of the British Archaeological Association 124 (1971): pp. 81–3, where Stalley argues both churches in Devizes post-date Roger’s death in 1139.

[21] On Bampton, see John Blair, ‘St Beornwald of Bampton’, Oxoniensia 49 (1984): pp. 47–55; Blair, ‘Bampton: An Anglo-Saxon Minster’, Current Archaeology 160 (1998): pp. 124–30; Baggs et al (eds.), Victoria County History, pp. 48-53.

[22] For a cautionary warning against assuming cruciform churches had enjoyed minster status, or that minsters were necessarily reconstructed to a cruciform plan, see Michael Franklin, ‘The Identification of Minsters in the Midlands’, Anglo-Norman Studies 7 (1984): pp. 69–88.

[23] Royal Commission on Historical Monuments of England, An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Herefordshire; Volume 2, East (London: HMSO, 1932), pp. 100–3. I am grateful to the anonymous reader for the rewording of this sentence.

[24] The earliest standing masonry at Bibury is eleventh-century and seems to belong to an aisleless two-cell church. On Bibury’s parochia see Blair, ‘Introduction: From Minster to Parish Church’, pp. 11–12. For an architectural description see David Verey and Alan Brooks, Gloucestershire 1: The Cotswolds (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1999), pp. 167–9.

[25] John Grundy, Nikolaus Pevsner et al, Northumberland (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1992), pp. 523–4.

[26] Richard Gem, ‘The Church of St Nicholas Old Shoreham: The Church of St Mary de Haura New Shoreham’, Archaeological Journal 142 (1985): pp. 21–3.

[27] Blair, ‘Clerical Communities and Parochial Space’, figure 12.4. See also Jill A. Franklin, ‘Iconic Architecture and the Medieval Reformation: Ambrose of Milan, Peter Damian, Stephen Harding and the Aisleless Cruciform Church’, in John McNeill and Richard Plant (eds.), Romanesque and the Past (Leeds: Maney Publishing, 2013), pp. 77–94. Franklin argues that until the middle of the twelfth century, churches built for regular canons were purposefully and specifically designed to an aisleless cruciform plan and that the plan was imbued with a set of meanings associated with the early Church that were given ‘renewed currency’ in the late-eleventh-century remodelling of the Basilica Apostolorum (San Nazaro Maggiore) in Milan.

[28] ‘A stereotyped plan—the ‘right’ way to rebuild an ex-minster if one had sufficient funds—had gained wide currency by the 1160s’. Blair, ‘Clerical Communities and Parochial Space’, p. 279.

[29] White Ladies Priory (Shropshire) is an example of an aisleless cruciform church where the nave ran through to the chancel without a western crossing arch (and therefore with no central tower). This type of plan tends to be associated with monastic churches, however, and as far as I am aware is not a feature of parish churches, at least not as primary builds. There are, of course, numerous examples of parish churches which arrive at cruciform plans without central towers as a result of piecemeal expansion. See, for instance, Polebrook (Northamptonshire), or Kelmscott (Oxfordshire).

[30] On the position and respective ‘ownership’ of the internal spaces within Romanesque parish churches and the position of altars, see Paul S. Barnwell, ‘The Laity, the Clergy and the Divine Presence: The Use of Space in Smaller Churches of the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries’, Journal of the British Archaeological Association 157 (2004): pp. 41–60. Barnwell does not include aisleless cruciform parish churches in his analysis, but the question of the position of their principal altar is the same as in the case with three-cell linear plans.

[31] David Stocker and Paul Everson, Summoning St Michael: Early Romanesque Towers in Lincolnshire (Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2006), p. 92.

[32] Stocker and Everson, Summoning St Michael , pp. 85–91.

[33] For Canterbury, see Dom David Knowles and Christopher Brooke (eds.), The Monastic Constitutions of Lanfranc (Oxford: Oxford Medieval Texts, 2002), pp. 185–93. Following the washing of the body of the deceased, the corpse is set on a hearse, covered with a pall and ‘placed in the usual position in the church’ at which point the bells cease to toll (positoque corpore in loco ubi poni solet, cessent signa). The bells are again tolled when the procession leaves the church and continue to be rung until the body is in the grave. Unfortunately, neither the position of the corpse in the church, nor the portal by which the funeral procession exits the church are specified.

[34] Stocker and Everson, Summoning St Michael, pp. 23–6, 34–43, figures 2.44 and 2.29. The west towers at St Peter Stanthaket and Great Hale were initially built forward of the nave, though the nave was subsequently extended west to meet them. See figure 2.12.

[35] Knowles and Brooke (eds.), Monastic Constitutions, pp. 60–70.

[36] Knowles and Brooke (eds.), Monastic Constitutions, p. 10, figure 2.7.

[37] Attempts have been made to relate these to the use of transept towers at Exeter Cathedral in the early-twelfth century. See Malcolm Thurlby, ‘The Romanesque Cathedral of St Mary and St Peter at Exeter’, in Francis Kelly (ed.), Medieval Art and Architecture at Exeter Cathedral (Leeds: W. S. Maney and Son, 1991), p. 29.

[38] Bridget Cherry and Nikolaus Pevsner, Devon, Buildings of England, second edition (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1989), p. 39.

[39] Stephen Heywood, ‘The Round Towers of East Anglia’, in Blair (ed.), Minsters and Parish Churches, pp. 169–77.

[40] Nikolaus Pevsner and Bill Wilson, Norfolk I: Norwich and the North-East, Buildings of England, second edition (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1997), p. 43.

[41] The Round Tower Churches Society website, accessed 1 June 2021, http://www.roundtowers.org.uk/about-round-tower-churches

[42] Stephen Heywood, ‘Stone Building in Romanesque East Anglia’, in David Bates and Robert Liddiard (eds.), East Anglia and its North Sea World in the Middle Ages (Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer, 2015), pp. 262–5, 268–9. The contention that the parochial round towers are modelled on the ambulatory chapels at Norwich Cathedral and Bury St Edmunds is, however, unconvincing. See also Heywood, ‘The Round Towers of East Anglia’, passim.

[43] Heywood, ‘Stone Building’, p. 263.

[44] For the Norwich customary, see John Basil Tolhurst, The Customary of the Cathedral Priory Church of Norwich: MS 465 in the library of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge (London, Henry Bradshaw Society 82, 1948)., folio 159v. The only surviving copy of the customary dates from the mid-thirteenth century, to which additions were made after 1277. The section dealing with the burial of a monk is among the later additions, entitled ‘Observancie in sepulture monachi’. This would appear to be highly abbreviated; indeed it is partly written in note form. It does not describe the burial, while the only bell mentioned is that rung before the commendation of the body to God. The corpse is left at the door to the cloister (ad hostiam claustri), though which door is not specified. The assumption here, as at Canterbury, is that the deceased was a monk. As death was most likely to have taken place in the monastic infirmary, the cloister door was probably at one or the other end of the east cloister walk. For the relationship between the Norwich customary and that of Fécamp, see Richard Pfaff, The Liturgy in Medieval England: A History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), pp. 203–7.

[45] J. Philip McAleer, ‘Surviving Medieval Free-Standing Bell Towers at Parish Churches in England and Wales’, Journal of the British Archaeological Association 156 (2003): pp. 79–103.

[46] The church of St. Benet at Cambridge is not untypical. Foundations for aisles were discovered during restoration work in 1853 (north aisle) and 1872 (south aisle), but were it not for the plan and measurements published by Willis and Clark little would be known of this. Robert Willis and John Willia Clark, The Architectural History of the University of Cambridge and of the Colleges of Cambridge and Eton, volume one (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1886), pp. 275–6, 281. The plan (noted as figure 1 in the text) is separately published in volume four, under Corpus Christi College. St. Benet was built in the mid-eleventh century as an aisleless three-cell church with tower, nave, and chancel. The aisle foundations discovered in the nineteenth century were ten feet wide and were probably built contemporaneously as a pair. As the advowson was given to the abbey of St. Albans during the abbacy of Paul of Caen (1077–93) it may be that the aisles were early additions.

[47] For Wing see Richard Gem’s church guide. R. Gem, All Saints Church Wing (Much Wenlock: R. J. L Smith, 2002). See also Eric Fernie, The Architecture of Norman England (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), tables 7 and 8, pp. 228, 230.

[48] In the course of a visit to Ickleton during the British Archaeological Association’s 2018 Cambridge conference, Frank Woodman raised the possibility of a date as early as c.1060 for the primary building phase of the church. The paired half-columns supporting the western arch of the tower counsel against a pre-Conquest date, but the parallels between the capitals and bases of the west portal and Gundulf’s crypt at Rochester Cathedral suggest a date of c.1080 is probable.

[49] William Page (ed.), Victoria County History: Cambridgeshire; Vol. 6 (Oxford: Institute of Historical Research, 1978), pp. 230–46. For the wall paintings see David Park, ‘Romanesque Wall Paintings at Ickleton’, in Neil Stratford (ed.), Romanesque and Gothic: Essays for George Zarnecki (Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer, 1987), pp. 159–69.

[50] For Hemel Hempstead see William Page (ed.), Victoria County History: Hertfordshire; Vol. 2 (London: Archibald Constable, 1908), pp. 215–30, and Royal Commission on Historical Monuments of England, An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Hertfordshire (London: HMSO, 1910), pp. 109–11, with a good plan. I exempt Holy Trinity, Great Paxton (Huntingdonshire) from this discussion, for although it is a small cruciform church with integral aisles dating from the middle of the eleventh century, it is most unlikely that it was built as a parish church. At the presumed date of its construction the surrounding estate was held by Edward the Confessor, and a charter issued by King David I of Scotland between 1124 and 1128 refers to a prior and canons regular serving the church. William Page (ed.), Victoria County History: Huntingdonshire; Vol. 2 (London: St. Catherine Press, 1932), pp. 328–32.

[51] Malcolm Thurlby, ‘The Romanesque Priory Church of St Michael at Ewenny’, Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 47 (1988): pp. 281–94; David Park and Sophie Stewart, ‘The Painted Decoraion of Ewenny Priory and the Development of Romanesque Altar Imagery’, in John Kenyon and Diane Williams (eds.), Cardiff: Architecture and Archaeology in the Medieval Diocese of Llandaff (Leeds: Maney Publishing, 2006), pp. 42–59. Thurlby’s is the fuller account of the architecture and convincingly argues for a single unitary build, though his preferred date of c.1111×16–1126 is discounted by Park and Stewart in favour of a date in the 1140s.

[52] See the discussion of plan types in C. J. Bond, ‘Church and Parish in Norman Worcestershire’, in Blair (ed.), Minsters and Parish Churches, pp. 138–41, especially the selection of plans illustrated in figure 34.

[53] For Kilpeck, see Malcolm Thurlby, The Herefordshire School of Romanesque Sculpture (Logaston: Logaston Press, 2nd ed., 2016), pp. 95-132; for Kempley, see Eric Gethyn-Jones, The Dymock School of Sculpture (Chichester: Phillimore, 1979), pp. 31–7; on the status of Kempley’s roofs see Beric M. Morley and Daniel Miles, ‘Nave Roof, Chest and Door of the Church of St Mary, Kempley, Gloucestershire: Dendrochronological Dating’, Antiquaries Journal 80 (2000): pp. 294–6.

[54] Until 1931 Blockley was a detached portion of Worcestershire. See William Page (ed.), Victoria County History: Worcestershire; Vol. 3 (London: Archibald Constable, 1913), pp. 265–76.

[55] For Cliffe see Mary Berg and Howard Jones, Norman Churches in the Canterbury Diocese (Stroud: The History Press, 2009), pp. 90–5; G. M. Livett, ‘Notes on the Church of St Margaret-at-Cliffe’, Archaeologia Cantiana 24 (1900): pp. 175–80. G.M. Livett’s measurements make it clear that the chancel at Cliffe is twelve metres (forty feet) long and, if measured from wall-centre to wall-centre, is a double square. Tim Tatton-Brown points out that Cliffe had a fine natural harbour in a circular bay (now largely eroded), and good access to fresh water. Despite being ‘overshadowed’ by Dover it is likely to have been a significant population centre in the twelfth century. Tatton-Brown, personal communication. See Edward Hasted, The History and Topographical Survey of Kent, second edition, (Canterbury: W. Bristow, 1800), volume nine, pp. 412–13 and map. For Norham see John Grundy, Nikolaus Pevsner et al, Northumberland (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1992), pp. 523–4. The surviving Romanesque fabric at Norham makes it clear its chancel was in excess of twelve metres long.

[56] Royal Commission on Historical Monuments of England, An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Northamptonshire: Volume 5 Archaeology and Churches in Northampton (London: HMSO, 1985), pp. 371–8; Henry Maguire, ‘A Twelfth-Century Workshop in Northampton’, Gesta 9 (1970): pp. 11–25: J. H. Williams, ‘Northampton’s Medieval Parishes’, Northamptonshire Archaeology 17 (1982): pp. 74–84; See also Ron Baxter’s entry on The Corpus of Romanesque Sculpture in Britain and Ireland, accessed 29 June 2021, https://www.crsbi.ac.uk/view-item?i=13446

[57] See, in particular, Ron Baxter’s CRSBI entry on https://www.crsbi.ac.uk/view-item?i=13446 for a description of the original corbels and capitals.

[58] For Wing, St. Michael at St. Albans, and Walkern see above.

[59] See Ron Baxter’s CRSBI entry on https://www.crsbi.ac.uk/view-item?i=13446 for an appraisal of the sculpture. The workshop seems to have had a significant business in equipping Northamptonshire parish churches with fonts.

[60] For reflections on the importance of varied pier design in Anglo-Norman architecture see Lawrence Hoey, ‘Pier Form and Vertical Wall Articulation in English Romanesque Architecture’, Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 48 (1989): pp. 258–83.

[61] Paul Barnwell argues this eastern area (chancel) should be subdivided into two spaces which he defines as a ‘central area’, which contained the altar, and an ‘apse’. The church is thus a type of three-cell building. See Paul Barnwell, ‘The Laity, the Clergy and the Divine Presence: The Use of Space in Smaller Churches of the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries’, Journal of the British Archaeological Association 157 (2004): pp. 51–2.

[62] The incidence of screens in twelfth-century parish churches is contested. There is some evidence in some churches for their use but how widespread this may have been remains uncertain. For a recent review see Carol Davidson Cragoe, ‘Belief and Patronage in the English Parish before 1300: Some Evidence from Roods’, Architectural History 48 (2005): pp. 21–48, especially pp. 30–1, 35–7. Paul Barnwell implies they were common currency. Barnwell, ‘The Laity, Clergy and Divine Presence’, pp. 46, 51–2.

[63] RCHME, Northamptonshire: Volume 5, pp. 57–9, 371–2. Its pre-Conquest past may also be reflected in its possession of the detached chapelries of Kingsthorpe and Upton.

[64] John H. Williams, Michael Shaw, and Varian Denham, Middle Saxon Palaces at Northampton (Northampton: Northampton Development Corporation, 1985). In excavations ahead of development in the late 1970s a large hall was discovered to the east of St. Peter’s. The first structure was built of timber and consisted of a central rectangular space flanked by annexes which was dated to the mid-eighth century. This was then replaced by a larger rectangular masonry hall in the early-ninth century, to which western chambers were added in the middle of the ninth century. The relationship between the hall(s) and St. Peter’s church to the west is unclear. Richard Gem followed the excavators in interpreting church and hall as a palace group. See Richard Gem, ‘Architecture of the Anglo-Saxon Church 735–870: From Archbishop Ecgberht to Archbishop Ceolnoth’, Journal of the British Archaeological Association 146 (1993): pp. 39–40. John Blair interprets the hall as a monastic building—a refectory—set between a royal minster (St. Peter’s) and the lesser church of St. Gregory which stood to the south-east. John Blair, The Church in Anglo-Saxon Society (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), p. 205.

[65] Norfolk Archaeology, 25 Part I (1932), pp. xxvii–xxix; Francis Blomefield and Charles Parkin, An Essay Towards a Topographical History of the County of Norfolk: Volume 9 (London: W. Miller, 1808), pp. 72–84.

[66] There is good evidence on the exterior that the easternmost fifteenth-century clerestory window replaced a late-twelfth-century window.

[67] For an account of the estate holders and the relationship with Ramsey Abbey see Blomefield and Parkin, Topographical History of Norfolk, pp. 121–31. Walsoken was owned by the abbey of Ramsey (Huntingdonshire) in which respect it is worth drawing attention to the parish church of St. Thomas Becket at Ramsey. See note 71 below. See also Nikolaus Pevsner and Bill Wilson, Norfolk 2: North-West and South (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1999), pp. 748–50. The survival of a two-bay aisled chancel that predates 1200 is worth underling.

[68] The charter is dateable to between 1158 and 1169. By this, Nigel, bishop of Ely, granted the monks of Ely one tree-trunk each week for work on their infirmary from the bishop’s wood at Somersham. Nicholas Karn, English Episcopal Acta 31: Ely 1109–1197 (Oxford: British Academy, 2005), no. 46. For a detailed appraisal of the Ely infirmary see A. Holton-Krayenbuhl, ‘The Infirmary Complex at Ely’, Archaeological Journal 154 (1997): pp. 118–72.

[69] For reflections on this see Stuart Harrison and John McNeill, ‘The Romanesque Monastic Buildings at Westminster Abbey’, in Warwick Rodwell and Tim Tatton-Brown (eds.), Westminster: I The Art, Archaitecture and Archaeology of the Royal Abbey (Leeds: Maney Publishing, 2015), pp. 74–9.

[70] Thomas of Walsingham, Gesta Abbatum Monasterii Sancti Albani, H. T. Riley (ed.) (London: Longman, Rolls Series, XXVIII, v. 4, 1867), I, p. 76.

[71] The evidence is perhaps best for Canterbury. Lanfranc’s hospital of St. John the Baptist was arranged as a partitioned rectangular dormitory block with detached service buildings, while the two relevant late-twelfth-century buildings—the Eastbridge hospital and the new domus hospitium at Christ Church Cathedral—were respectively arranged as a hall flanked by a single side aisle with a rectangular chapel to the east (all above vaulted cellars), and as a vaulted two-storey twin-aisled hall with internal ramped stairs. See Paul Bennet, ‘St John’s Hospital and St John’s Nursery, Archaeologia Cantiana 108 (1990): pp. 226–31; Peter Fergusson, Canterbury Cathedral Priory in the Age of Becket (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011), pp. 59–79. Fergusson includes an extended discussion of monastic and cathedral guesthouses, particularly in East Anglia. The parish church of St. Thomas Becket at Ramsey (Huntingdonshire) has been claimed as a converted monastic guesthouse or hospital on the grounds there is no evidence for a church tower before 1538, though this seems a flimsy reason to reassign a building whose surrounds haven’t been fully excavated and which houses an early-thirteenth-century font. See RCHME, An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Huntingdonshire (London: HMSO, 1926), pp. 204–7, and Ron Baxter’s entry for the CRSBI – https://www.crsbi.ac.uk/site/603/. Baxter favours a date of c.1180 for the surviving arcade, though a date of c.1190–1200 seems more likely to me. I am grateful to Richard Halsey for discussing Ramsey with me.

[72] One would not know from the exterior that Walsoken is still, fundamentally, a late-twelfth-century church. Nor Long Sutton. The expansion has taken place around the edges. Both have been widened and heightened.

[73] Nikolaus Pevsner and Enid Radcliffe, Suffolk, second edition (London: Penguin, 1974), pp. 463–4; see also Ron Baxter’s CRSBI entry at https://www.crsbi.ac.uk/site/758/

[74] On the date of Iffley see Mark Phythian-Adams, ‘The Patronage of Iffley church—A New Line of Enquiry’, Ecclesiology Today 36 (2006): pp. 7–24.

[75] For Compton see H. E. Malden (ed.), Victoria County History: Surrey; Vol. 3 (London: Archibald Constable, 1911), pp. 21–4.

[76] The church at Castor deserves a monograph. For the moment, the best general account is Charles O’Brien and Nikolaus Pevsner, Bedfordshire, Huntingdonshire and Peterborough (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014), pp. 454–6. The best account of the twelfth-century phases of the church is the CRSBI entry at https://www.crsbi.ac.uk/site/371/

[77] Simon Townley (ed.), Victoria County History: Oxfordshire; Vol. 17, (Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer, 2012), pp. 209–33. The assumption has been that Little Faringdon church was given a north aisle after King John transferred the manor of Little Faringdon to his new Cistercian foundation at Great Faringdon (Berkshire) in 1203 (moved to Beaulieu in Hampshire in 1204), though there is no reason to link the two. Little Faringdon was a chapel-of-ease of the parish church of Langford, and that tie was unaffected by the change of manorial tenant. Nevertheless, a date at the beginning of the thirteenth century for the aisle does seem probable. The aisle is comparable to neighbouring Kelmscott (see below) though given the rich mouldings and confident handling of the stiff leaf capitals Little Faringdon is likely to postdate Kelmscott.

[78] William Page (ed.), Victoria County History: Hertfordshire; Vol. 2 (London: Archibald Constable, 1908), pp. 368–71. The arcade at Redbourn is similar to that at Hemel Hempstead but is more likely to have been built c.1160, rather than 1140 as suggested by the VCH. The manor and parish church at Redbourn were possessions of St. Albans Abbey.

[79] See, for example, Morris, Churches in the Landscape, pp. 287–95; Fernie, Architecture of Norman England, pp. 227–32; Peter Draper, The Formation of English Gothic: Architecture and Identity (London: Yale University Press, 2006), pp. 183–5.

[80] L. J. Proudfoot, ‘The Extension of Parish Churches in Medieval Warwickshire’, Journal of Historical Geography 9 (1983): p. 244.

[81] Proudfoot, ‘The Extension of Parish Churches’, table 1, p. 234.

[82] Morris, Churches in the Landscape, pp. 289–92.

[83] See T. A. Heslop, ‘Size Matters: Norwich Churches and Their Parishioners before the Reformation’, in David Harry and Christian Steer (eds.), The Urban Church in Late Medieval England (Donington: Shaun Tyas, 2019), pp. 63–81.

[84] For a summary, see John McNeill, ‘A Prehistory of the Chantry’, Journal of the British Archaeological Association 164 (2011): pp. 12–14.

[85] Warwick Rodwell, St Peter’s, Barton-upon-Humber, Lincolnshire: A Parish Church and its Community, History, Archaeology and Architecture; Volume 1, Part 2 (Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2011), pp. 619–20 and figure 698. The pathology and dating are discussed in Tony Waldren, St Peter’s, Barton-upon-Humber, Lincolnshire: A Parish Church and its Community, The Human Remains; Volume 2 (Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2007).

[86] Rodwell dated the first north nave aisle to c.1180–1200, and the first south nave aisle to slightly later. Rodwell, St Peter’s, Barton-upon-Humber, Volume I, Part 1, pp. 383–5.

[87] Rodwell, St Peter’s, Barton-upon-Humber, Volume I, Part 1, p. 385.

[88] An arch connecting the south aisle with the south transept was constructed when the south aisle at Castor was built. See figure 21.

[89] For New Shoreham see Sally Woodcock, ‘The Building History of St Mary de Haura, New Shoreham’, Journal of the British Archaeological Association 145 (1992): pp. 89–103.

[90] McNeill, ‘St Wulfram: 3’, p. 97.

[91] Lawrence Hoey, ‘The Early Gothic Parish Church Architecture of Nottinghamshire’, in Jennifer S. Alexander (ed.), Southwell and Nottinghamshire: Medieval Art, Architecture and Industry (Leeds: Maney Publishing, 1998), pp. 73–82.

[92] For Kelmscott see Carol Davidson Cragoe, ‘Kelmscott Church: Context and History’, in Alan Crossley, Tom Hassall, and Peter Salway (eds.), William Morris’s Kelmscott: Landscape and History (Macclesfield: Windgather Press, 2007), pp. 56–67. For St. Mary at Barton-upon-Humber see Rodwell, St Peter’s, Barton-upon-Humber, Volume 1, Part 1, pp. 97–102. For St.-Nicholas-at-Wade, see Berg and Jones, Norman Churches in the Canterbury Diocese, pp. 103–4.

[93] For reflections on high-status axial western towers in the tenth and early-eleventh centuries see Richard Gem, ‘Staged Timber Spires in Carolingian North-East France and Late Anglo-Saxon England’, Journal of the British Archaeological Association 148 (1995): pp. 29–54, especially pp. 44–50.