Big Data is not a concept commonly deployed in the discipline of architectural history. The material collected for my own doctoral research on the sixty-six collegiate churches founded in England and Wales in the fourteenth century was extensive but did not constitute Big Data. It included information on the colleges’ statutes, rules and regulations; their patrons, size and funding; and data on the stylistic motifs deployed in the main fabric of the buildings associated with each college together with analysis of all their extant micro-architecture. Such an array of information, common not just to my own endeavour but to the great majority of projects researching medieval architecture, might more reasonably be termed Big(ish) Data; a not inconsiderable dataset but one that an individual can still keep track of, know its little idiosyncrasies, adjust for its lacunae, and account for its anomalies.1

Big Data, by contrast, goes beyond the purview of any one researcher in two respects. The first is simply the volume of data collected. The second, more subtle difference lies in the objectives of study. Big(ish) Data, as described above, is most often collected with the aim of answering or addressing a specific question, or a limited number of questions. Big Data, on the other hand, should be capable of being used to answer any number of questions. It therefore demands structure and the collection, collation, and presentation of information such that it can be available for many disparate uses. It requires a different and more exacting approach.

This paper aims to use the experience gained in recording and analysing the fourteenth-century colleges to provide insights into the benefits to be gained from treating aspects of medieval architecture as a defined dataset and also the challenges and potential pitfalls of recording information on medieval parish churches on a scale, and to a specification, that is Big Data.

The Potential Benefits

Comprehensive and consistent information on a large number of medieval parish churches would, at minimum, greatly extend our knowledge. But the availability of large volumes of data also facilitates novel and insightful forms of analysis. For example, in the investigation of the causes of architectural change it enables the use of a different way of defining and examining change itself.

The so-called ‘population-level’ approach, developed in the late 1950s and used extensively in the natural sciences, utilises information on the whole of the population under study, not just a selected sample. It defines change as the differential persistence of variants or traits within a population over time, as measured by their frequency distribution.2 This is very different from the approaches usually adopted in architectural history. The typological method for analysing change, for example, tracks the instances of a particular feature or motif, such as double-ogee mouldings or four-centred arches, over time and space, while paying particular attention to precedents and antecedents. An alternative, which might be termed a ‘dialectical’ approach, determines two groups of buildings from different time periods and then compares and contrasts the formal elements within each: a method most clearly articulated by Heinrich Wölfflin in his comparative analysis of Renaissance and Baroque art and architecture.3

Examples of the potential benefits of a ‘population-level’ approach are warranted here: the first relates to the foundation of colleges rather than their architecture. It is often stated that there was a strong connection between the setting up of the Order of the Garter by Edward III in 1348, the king’s coincident conversion to collegiate status of both St. Stephen’s, Westminster and St. George’s, Windsor, and the subsequent foundation of collegiate churches by Garter Knights.4 This common proposition is based on such noteworthy examples as the colleges of Newarke (converted from a hospital by Henry Grosmont, then Earl of Lancaster), Pleshey (founded by Thomas Woodstock, Duke of Gloucester), and Fotheringhay (by Edmund, Duke of York). All were Garter Knights. But taking a population-level view, it is difficult to sustain such a generalisation. Of all the Garter Knights, from the Order’s inception to the death of Richard II in 1399, fewer than eight percent (those shown in red in Fig. 1) went on to found a college.5 Even after excluding foreign Knights and those whose family had already founded a college, the figure only rises to ten percent. And many of those that did go on to create a new institution did so many decades after 1348. Thomas Woodstock, for instance, did not found his college until 1394 and Edmund, Duke of York not until the fifteenth century.6

The illumination of ecclesiastical spaces through the period of Gothic architecture provides another example. It is often assumed that this is characterised by a gradual but steady increase in illumination, through more of the surface area of church elevations being given over to glass. For college church buildings of the middle and latter parts of the fourteenth century, the proposition can be illustrated with reference to the well-illuminated St. Mary the Less in Cambridge, the college of St. Mary’s at St Davids (Pembrokeshire), or at the chapel of New College, Oxford. But taking the wider view raises some legitimate questions, notwithstanding the difficulties caused by our lack of definitive knowledge of the original glazing of these windows. There are many well-illuminated chancels in the early part of the century: to take just two examples, those at the Carnary Chapel in Norwich, and at Sibthorpe in Nottinghamshire. Conversely, there are many rather dark spaces towards the end of the century. Cobham (Kent), where work on converting the church to collegiate status began in the 1360s, retained its narrow thirteenth-century windows. At Bunbury (Cheshire) the chancel was extended in the 1380s, but no attempt was made to increase the level of illumination; the old windows were re-used.7 Examples are not limited to conversions of earlier churches. The side windows of the newly built chancel at St. Mary’s, Warwick, from the 1380s, have remarkably high sills and blocked lower sections making the area particularly dark.8 The windows of Winchester College chapel are also characterised by high sills that, in combination with deep recesses and extensive external buttresses, work to reduce the lighting level within.9 In the latter part of the century patrons were apparently content to retain comparatively ill-lit chancels from earlier periods or erect new buildings whose design decisions indicate that illumination was not a critical factor.

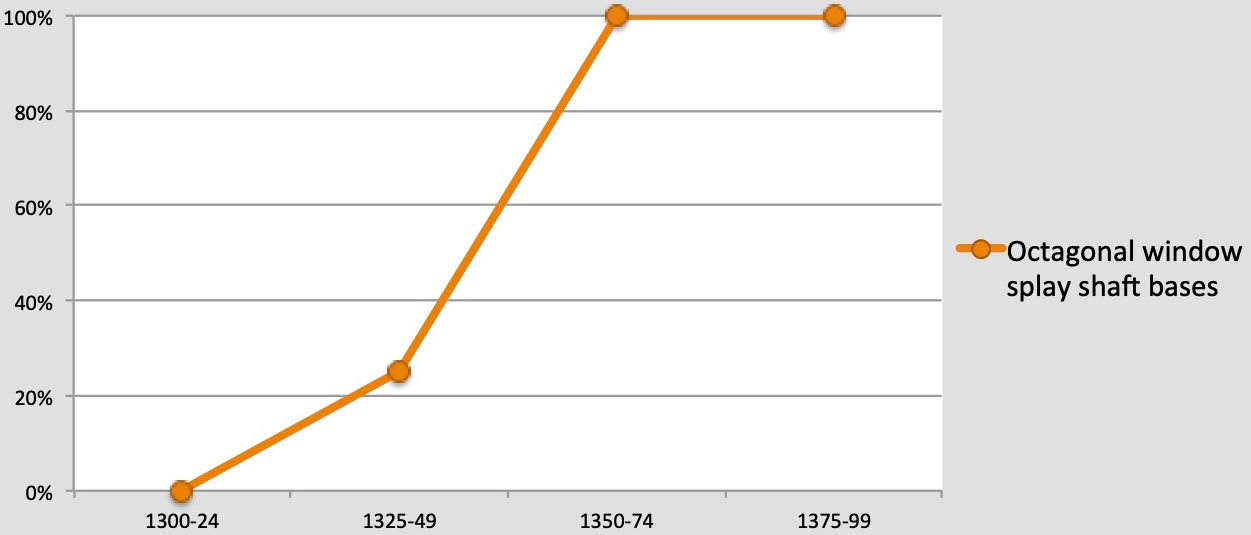

These examples could, of course, simply be characterised as ensuring that any evidence is placed in its correct context. But the population-level approach, and its corresponding definition of change, can provide new insights that go beyond the benefit of simply having more data and taking the appropriate perspective. Foremost among these is the ability to construct frequency distribution graphs. By way of explanation, the occurrences of a particular motif among collegiate church building work within a period of time (say between 1300 and 1324, 1325 and 1349, and so on) can be recorded and then expressed as a percentage of all the collegiate building campaigns taking place in that quarter. Each quarter’s percentage is then plotted on a graph. Figure 2 illustrates the prevalence or otherwise of a single motif—octagonal window splay shaft bases—in collegiate church building campaigns throughout the fourteenth century. From this one can conclude that there was little or no use of the motif in the first quarter, and then a very quick take up in the middle of the century until it was ubiquitous by the second half.

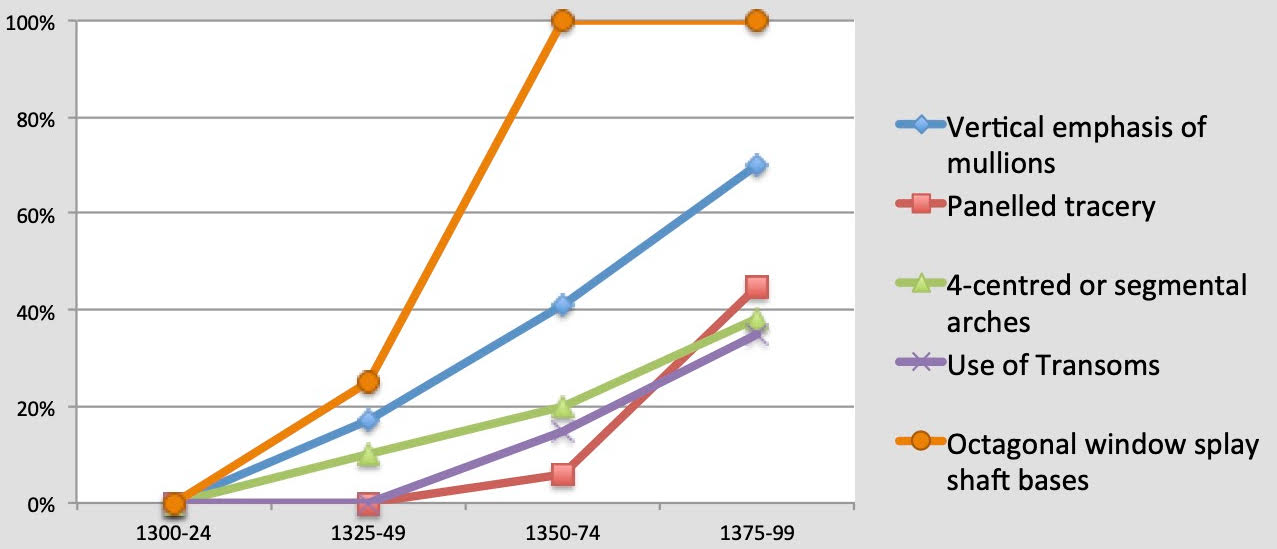

There are numerous uses to which this form of analysis can be put, but three may briefly be mentioned. The technique enables a succinct way of presenting the introduction of various motifs and the timing and pace of their subsequent diffusion. Further, if several motifs are combined, as in Figure 3 which presents a number of features often associated with the term ‘Perpendicular’, then the degree to which the motifs were taken up as a total package or introduced on a more piecemeal basis can be ascertained. A close alignment of the graphs of the motifs would suggest introduction en bloc: the further apart the lines, the more sporadic the adoption of the individual motifs. Thirdly, the emerging shape of the frequency graphs illustrated here is, potentially, instructive. To put it descriptively, the rate of introduction of motifs starts slowly, accelerates, and then levels off. More technically, the graphs describe a sigmoidal or S-shaped curve. The critical point in such an observation is that sigmoidal curves of adoption are extremely common in studies of the diffusion of innovation. Since the 1930s, there have been over five thousand such studies, ranging from the introduction of new forms of maize, through to new medical treatments, and domestic technologies.10 The adoption of almost all these innovations exhibited an S-shaped curve. It is perhaps therefore what one should expect for the introduction of new architectural motifs. Awareness of the applicability of sigmoidal adoption curves might aid the analysis of architectural change. The important point for this paper is that this form of analysis, whilst possible with Big(ish) Data, becomes more readily available, and more convincing, with access to Big Data.

The capabilities of using such a technique should not be overstated: it supplements rather than replaces more traditional methods of analysis. In an analysis of the tombs of founders of fourteenth-century colleges, for example, the frequency distribution graph clearly shows that there was a marked reduction in the use of wall tombs through the century (Fig. 4a), but in most other respects the picture was one of continuity rather than change. The proportion situated on the north of the chancel or at its centre did not alter much, nor did the form of the surviving tomb chests, these being fairly evenly distributed between those with weeper figures and those with a mix of panels and heraldry (Fig. 4b).11 Similarly, the division between effigies and brasses was remarkably consistent throughout the period (Fig. 4c). The population-level approach is, however, particularly adept at identifying anomalies. The tomb of William Trussell at Shottesbrooke (Berkshire) is the only example of a patron choosing to be buried in the north transept of his church when the chancel was available. Adam Houghton’s tomb at the college of St. Mary’s at St. Davids is also unusual in several respects. Not only is it a wall tomb from the latter part of the century, but it was significantly larger than all its surviving contemporaries (this regrettably now only indicated by the mutilation of the north wall of the chapel). Moreover, of the eleven bishops to found colleges in the century, only Adam Houghton was buried in his collegiate foundation. All the others chose their cathedrals, though it should be noted that Houghton’s college was adjacent to his cathedral. There is a clear sense, in this instance, that the great churches were thought to provide a more effective salvific location.

The population-level approach, together with the use of frequency distribution graphs, is not a panacea for the study of change in medieval ecclesiastical architecture, but it can be a powerful tool when Big (or even Big-ish) Data are available. There are difficulties, however, in obtaining such data on the architecture of parish churches.

Issues to be Addressed

The primary issues reside in three broad categories, each with their own particular set of challenges. The first, and perhaps the more straightforward, is to determine what should, ideally, be collected. As discussed above, much of the information gathered on the architecture of parish churches has been part of exercises with their own specific purposes and objectives. The data needed for doctoral research—in terms of structure and, potentially, detail—vary from that obtained for broader amalgamations such as the information collected and presented for the official listing of buildings. Big Data cannot allow such variation in data collection. Such datasets need to be capable of being used in multiple ways. In particular, they should be additive so that information on one parish church can be readily compared with that of another. This requirement spawns several important questions: precisely what data should be collected; how should they be defined, delineated, and categorised; how detailed ought the dataset to be; how might new technological methods of recording data, such as photogrammetry and three-dimensional modelling, be incorporated?

As an example of the sorts of decisions that must be made if data are to be capable of being additive or cumulative, the research undertaken into the architecture of the sixty-six collegiate churches founded in the fourteenth century required a hierarchical framework of architectural features to be determined. General information was collected on the location and geographical setting of each church along with its plan and dimensions. The recording of the architectural features then had three levels: ‘architectural elements’ (such as arcades, windows, sedilia and so on) were broken down into ‘component parts’ (thus, as an example, arcades comprised the components of arch shape, arch decoration, pier shape, capital type, and base type) and then each component part was categorised according to its ‘traits’. So, for the component ‘pier shape’ the trait categories were round, square, octagonal, hexagonal, two-shafted, four-shafted, moulded and so on. For the component ‘arch shape’ they were two-centred, four-centred, segmental etc. This provided a structure for data collection, and for subsequent analysis. A skeleton example of the hierarchy is shown in Figure 5.

The key point here is that the structure devised was appropriate for the questions being asked of the material: in this case, what was changing in terms of architectural style. The scale of individual features was noted, but detailed measurements, for example of the diameters of the piers, were not taken. The key elements of individual mouldings were recorded, but moulding profiles were not. In order to address different questions, such detailed measurements and profiles might be necessary, or indeed a different hierarchy for data collection might be appropriate.

A useful dataset for parish church architecture over two or three centuries moves away from the realm of Big(ish) Data, where one person can decide the structure, to that of Big Data where the information collected needs to meet multiple needs and requirements. Too loose a structure and the data are of little practical use, other than as a broad indication or a swift introduction. Conversely, an overly-prescriptive structure rather dampens the enthusiasm of those recording the information. Some of these problems can be resolved by using relational databases, as opposed to the databases of twenty or thirty years ago that required a strict and unmovable structure in order to proceed. But if research into parish churches is to be well-grounded and cumulative, rather than an ever-increasing set of disparate descriptions of buildings, then some discipline is required.

The second challenge is a central concern for all historians of medieval architecture: the dating of the material evidence. One of the benefits of choosing fourteenth-century collegiate churches to form the basis of an analysis of architectural change was that there is documentary evidence, if not for actual building campaigns, then for the dates of foundation, of key endowments, of college statutes and charters, of the necessary inquiries into transfers of ownership, and of the wills of their founders. This information enables reasonably confident timelines to be established for the various building campaigns of the sixty-six collegiate churches. In fact, it is probably not overstating the case to say that more is known about the dating of many collegiate churches than of the relatively few great church building campaigns in the latter part of the century. The dating of important developments such as the west front of Winchester Cathedral and the cloisters at Gloucester Abbey remain matters of on-going debate.12

So while the dating of collegiate building campaigns can be estimated with some confidence, one suspects that such analysis for parish churches as a whole will be more circumscribed. The common responses to this comparative lack of evidence are twofold. One is to fall back on the broad classification of architectural styles in medieval England, consolidated, now more than two hundred years ago, by Thomas Rickman.13 The simplicity of Rickman’s categories, together with the didactic nature of many of the early publications that used them, contributed to their popularity.14 The pervasive use of ‘Dec’ and ‘Perp’ in the Buildings of England series provides ample testament. The second response is to use stylistic evidence as a guide to dating. But not only does this produce somewhat circular arguments, the evidence from the fourteenth century suggests that it reinforces a somewhat linear narrative for stylistic change and is therefore open to error. The elevations of Ottery St Mary (Devon), for example, have, at various times, been thought to be from the thirteenth century, rather than from the 1340s, due to their retention of lancet windows.15 The chapel of Queen’s College, Oxford is firmly dated, through the college accounts, to the 1370s, yet its east window—if the detail of David Loggan’s seventeenth-century drawing is accurate—had a curvilinear design more common decades earlier.16 The innovative conoidal vaults and traceried wall surfaces of William Trussell’s tomb at Shottesbrooke would not normally be placed to the early 1340s without its exterior relieving arches and good documentation for the church’s construction providing ample evidence for such a date.17 To further compound the problem, there is often insufficient clarity as to whether the term Perpendicular is now being used to reference various motifs consistent with Rickman’s classification (and Rickman was quite forensic in this regard), or whether the term is being used to specify a particular time period for construction. For Big(ish) Data, the individual researcher can be aware of the problems that indeterminate dating or imprecise definition of terms might bring. Such a luxury is not available for Big Data.

The third challenge may prove to be the most intractable. Data structures and, at least to an extent, the dating of material can be addressed. They require coordinated effort resulting in clear, but perhaps not over-prescriptive, guidance. But in order to deliver a comprehensive dataset for medieval parish churches these ‘technical’ problems need to be placed alongside the less tangible issue of organising the necessary data collection. Big Data presents problems of scale. The data-gathering for sixty-six collegiate churches, of which about forty-five had substantive extant fabric, consumed about half the time allowed for the doctoral research. And, as noted above, the data collected would not address the multitude of questions that might be asked. No individual can encompass all of the medieval parish churches of England and Wales to the required detail. It is unlikely that a small group can do so within a reasonable timeframe. Such an endeavour will require a collaborative effort on the part of a sizable number of people, and such an effort requires structure and organisation.

Experience suggests that success depends on three organisational constructs working well together. The first is an established body or organisation, one recognised as having an interest in parish church architecture and willing and able to act as the focal point for the endeavour. Its status should ensure that any funding applications are well received and that it is capable of being a repository for the information collected. The second is some form of coordinating group that would be responsible for the resolution of the technical issues outlined above. It would set up the necessary communication and education and could play a role in troubleshooting, quality verification, and monitoring. It would be the focal point for liaising with other interested parties. The understanding and insights gained in developing the Corpus of Scottish Medieval Churches would clearly be of considerable importance here.

The last, and in many ways most important element is the not-inconsiderable number of engaged, energised, and enthusiastic volunteers actually undertaking the collection of the information on the parish churches themselves. There are many different models for how this might be achieved and ‘one size does not fit all’. Tradition, however, suggests that a county-based system would be most appropriate: the Buildings of England series and Victoria County Histories provide good examples. The county retains a local focus, it breaks the problem into more manageable pieces, and opens the possibility of engaging fully with existing organisations that have an interest in parish church architecture.

There are considerable benefits to be gained from applying the principles of Big Data to the study of medieval architectural history. Over and above the simple advantages of having a greater repository of information, it can expand the ways in which the material can be examined. There are, however, significant challenges involved in gathering the necessary information, and these will not just, or even primarily, be technical in nature. The biggest challenge will be to encourage the necessary wider engagement and establish the momentum required to sustain the endeavour over time.

Citations

[1] Recent exceptions to this general proposition of a lack of Big Data in research into medieval architecture include James A. Cameron, ‘Sedilia in Medieval England’ (PhD diss., Courtauld Institute of Art, 2015) and Lucy Wrapson, ‘Patterns of Production: A Technical Art Historical Study of East Anglia’s Late Medieval Screens’ (PhD diss., University of Cambridge, 2014).

[2] This definition of change is derived from biology and has recently been used in archaeology to provide quantified and mathematically-testable analyses of change in the archaeological record. See Ernst Mayr, ‘Typological Versus Population Thinking’, in Elliott Sober (ed.), Conceptual Issues in Evolutionary Biology, third edition (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006), pp. 325–8, and, for useful introductions and commentary, Elliot Sober, ‘Evolution, Population Thinking, and Essentialism’, in Sober, Conceptual Issues, pp. 329–59, and Elliot Sober, ‘Models of Cultural Evolution’, in Sober, Conceptual Issues, pp. 535–51. For the early methodological discussions within archaeology, see George T. Jones, Robert D. Leonard, and Alysia L. Abbott, ‘The Structure of Selectionist Explanations in Archaeology’, in Patrice A. Teltser (ed.), Evolutionary Archaeology: Methodological Issues (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1995), pp. 13–32, and Patrice A. Teltser, ‘The Methodological Challenge of Evolutionary Theory in Archaeology’, in Teltser, Evolutionary Archaeology, pp. 1–11.

[3] Wölfflin acknowledged that ‘everything is transition’ but his method for examining the causes of change between the Renaissance and Baroque clearly relies upon grouping buildings and artworks before making comparisons. See Heinrich Wölfflin, Principles of Art History, the Problem of the Development of Style in Later Art, (trans.) M. D. Hottinger (New York: Dover, 1950), particularly p. 227.

[4] This assertion is common. See, for example, Clive Burgess, ‘St George’s College, Windsor: Context and Consequence’, in Nigel Saul (ed.), St George’s Chapel, Windsor, in the Fourteenth Century (Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer, 2008), pp. 89, 92; Sally Badham, ‘“Beautiful Remains of Antiquity”: The Medieval Monuments in the Former Trinitarian Priory Church at Ingham, Norfolk. Part 1: The Lost Brasses’, Church Monuments 21 (2006): p. 11; Linda Monckton, ‘The Collegiate Church of All Saints, Maidstone’, in Tim Ayers and Tim Tatton-Brown (eds.), Medieval Art, Architecture and Archaeology at Rochester (Leeds: Maney, 2006), p. 301; and John Richards, ‘Sir Oliver de Ingham (d.1344) and the Foundation of the Trinitarian Priory at Ingham, Norfolk’, Church Monuments 21 (2006): p. 37.

[5] The information on the Garter Knights is taken from Hugh Collins, The Order of the Garter, 1348–1461: Chivalry and Politics in Late Medieval England (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2000). In this analysis Thomas Beauchamp is taken as having refounded his college at Warwick in the 1360s, see Andrew Budge, ‘The 14th-Century Rebuilding of the Collegiate Church of St Mary’s, Warwick’, Journal of the British Archaeological Association 170 (2017): p. 82.

[6] For a more detailed analysis, see Andrew Budge, ‘Collegiate Churches founded in the Fourteenth Century: Change in Architectural Style as a Social Process’, in John Munns (ed.), Decorated Revisited: English Architectural Style in Context, 1250–1400 (Turnhout: Brepols, 2017), pp. 40–1.

[7] For the changes at Bunbury see Maurice H. Ridgway, ‘The Sanctuary of Bunbury Church: Excavated 1952–53’, in Maurice H. Ridgway (ed.), The Bunbury Papers, nine volumes (Private subscription: 1949–60), vol. V (1954), accessed 1 June 2021, https://4e083a16-4603-4511-bc68-0e3c843b15b7.filesusr.com/ugd/2ae44a_59f84b87051340bba2969ae48fdc07cc.pdf

[8] For the dating of the Warwick chancel see Budge, ‘St Mary’s, Warwick’, pp. 94–5.

[9] The thick walls and narrow windows of the Winchester College chapel might be due to the nature of the ground on which the chapel was built. St. Elizabeth’s College, only 200m to the east of the chapel and erected in the first years of the fourteenth century, was built on a thick raft of chalk to counteract the soft ground. It is therefore possible that precautions were also taken for the later chapel. The taller elevations at New College, also designed by William Wynford and of a similar date, are both thinner and less prominently buttressed. For what is published on the construction of St. Elizabeth’s College, see Richard Whinney, ‘Excavations at St Elizabeth’s College, Winchester, 2011’, Hampshire Field Club Newsletter 57 (2012): pp. 13–15.

[10] The history of innovation diffusion research is set out in Everett M. Rogers, Diffusion of Innovations, fifth edition (New York: The Free Press, 2003).

[11] This mix of figured and panelled tomb chests was also seen in the fourteenth-century royal tombs. Mark Duffy’s analysis does, however, indicate a preference for ‘dynastic’ tomb chests in the fourteenth century with a shift to ‘panelled heraldic’ in the fifteenth. See Mark Duffy, Royal Tombs of Medieval England (Stroud: Tempus, 2003), particularly Fig. 75.

[12] For the various dates proposed for the Gloucester cloisters, see Walter C. Leedy, Fan Vaulting: A Study of Form, Technology, and Meaning (London: Scolar, 1980), p. 168; John H. Harvey, The Perpendicular Style, 1330–1485 (London: Batsford, 1978), p. 92; and Christopher Wilson, ‘The Origins of the Perpendicular Style and Its Development to Circa 1360’ (PhD diss., University of London, 1980), p. 260. For Winchester west front, see Harvey, The Perpendicular Style, p. 90 and Wilson, ‘Origins’, p. 300.

[13] Rickman, Thomas, An Attempt to Discriminate the Styles of English Architecture, From the Conquest to the Reformation(London: Longman, 1817).

[14] Rickman’s descriptive terminology was swiftly adopted by early-nineteenth-century writers. See, for example, Matthew Holbeche Bloxam, The Principles of Gothic Ecclesiastical Architecture [1829], fourth edition (Oxford: J. H. Parker, 1841); William Whewell, Architectural Notes on German Churches; With Remarks on the Origin of Gothic Architecture [1830] (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013); and John Henry Parker, A Glossary of Terms Used in Grecian, Roman, Italian, and Gothic Architecture [1836], fifth edition (Oxford: J. H. Parker, 1850).

[15] See, for example, John Neale Dalton, The Collegiate Church of Ottery St Mary (Cambridge: University Press, 1917), p. 11; John Coleridge, ‘Restoration of the Church of S. Mary the Virgin, at Ottery S. Mary’, Transactions of the Exeter Diocesan Architectural Society IV/I (1850): pp. 214–15; and Paul Jeffery The Collegiate Churches of England and Wales (London: Robert Hale, 2004), p. 146.

[16] The construction date of the chapel is well-attested through its building accounts. See John R. Magrath, The Queen’s College (Oxford: Clarendon, 1921), particularly pp. 69–73. The chapel was taken down in 1719 but its east window is shown in Loggan’s 1675 engraving of the college, reproduced in Magrath, The Queen’s College, Plate XXXI.

[17] For detailed discussion of the Trussell tomb, see Budge ‘Social Process’, pp. 46–7.