Charles T. Little

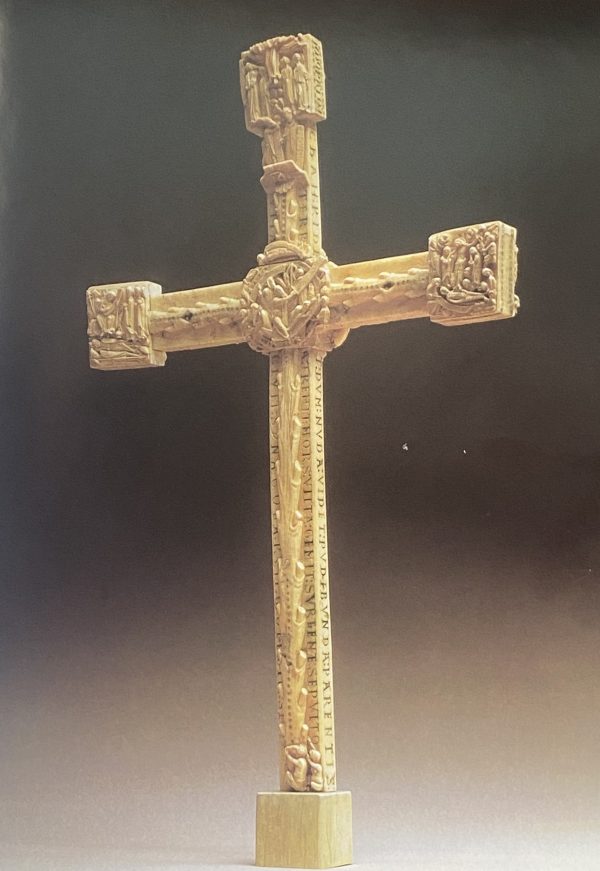

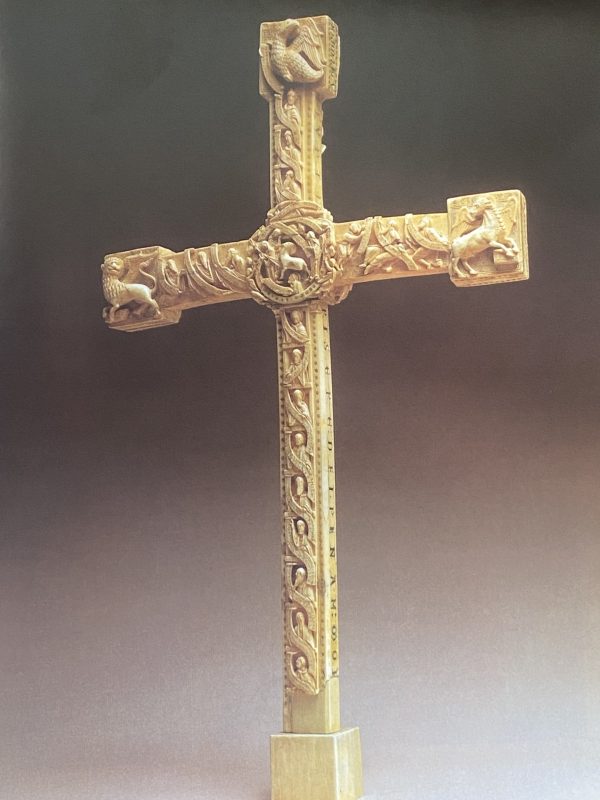

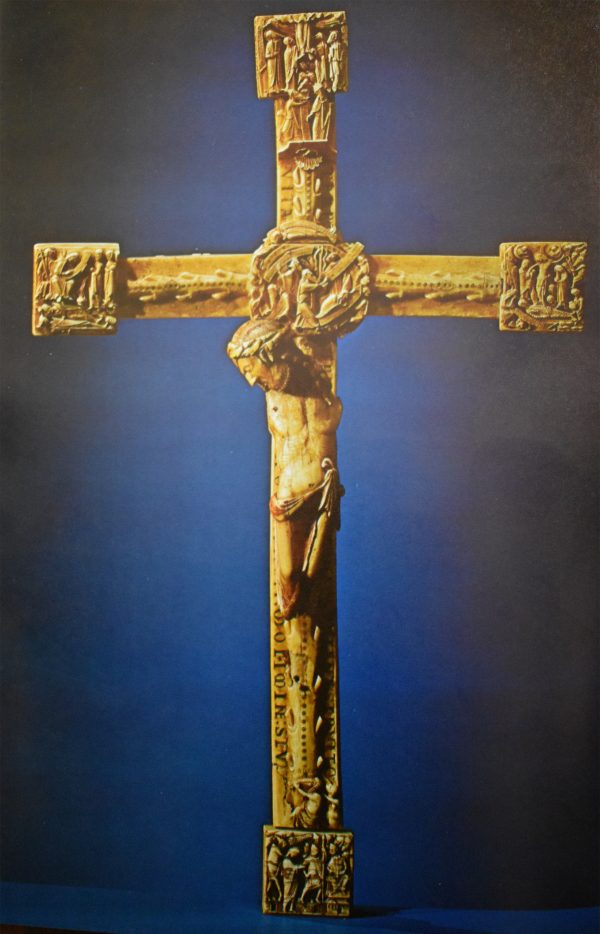

The walrus-ivory cross, now called the Cloisters Cross (Figs. 2.1 and 2.2) is displayed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s medieval branch called the Cloisters. Its purchase was provided by an endowment established by John D. Rockefeller Jr. (1874–1960) for the enrichment of its collection.1 It has resided there since 1963, except for short sojourns to the museum’s main building on Fifth Avenue in New York for the 1970 exhibition The Year 1200 and for loan exhibitions in London, Oslo, Venice, and Milan.

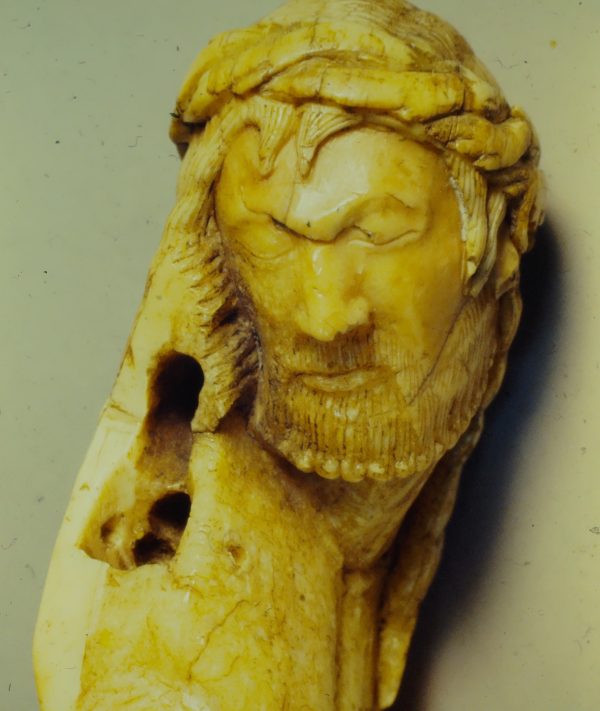

The Cloisters Cross now stands about twenty-three inches (57.7 cm) high, with its entire surface covered with narrative and symbolic scenes incorporated on a Tree of Life cross with more than ninety-two figures, and ninety-eight inscriptions.2 A seemingly clear inference is that the Cross was not intended for a large public liturgical ceremony. This is especially clear if the Cross is seen by candlelight, as it certainly was in a darkened church setting. Using a replica of the Cross with this condition in mind, it indeed radiates ‘through a glass darkly’ (Fig. 2.3). In the current display of the Cross in the Cloisters Treasury, the lower light levels reinforce this fact. Also, self-evident and recognized immediately—especially with a strong light—are its superb artistic qualities and detailed craftsmanship. The microcarved standing figures are under 4 centimetres and some less than 2.5 centimetres; the Evangelist symbols are the largest (4.5 x 4.5 cm). The carvings are taken to an exceptional level of detail in a medium that is not as easy to work as elephant ivory. Emotion is conveyed mostly by gesture. The energy of the figures can be easily seen when they are enlarged photographically and monumentalized with ‘digital gymnastics’, thus opening new frontiers for study and enlightenment.

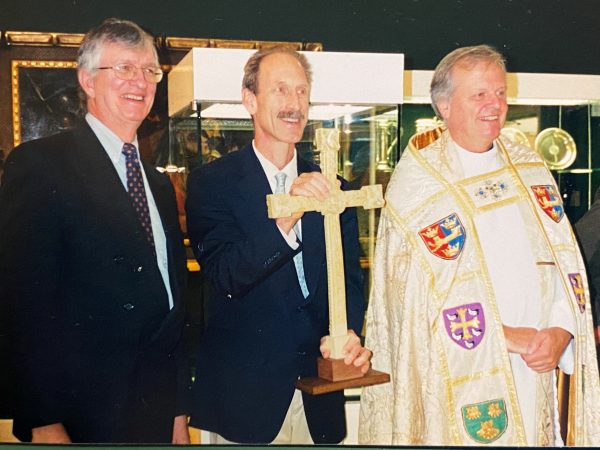

In 2003 the Met was approached by the dean of St Edmundsbury Cathedral (Suffolk), the Very Reverend James Atwell, who requested a replica of the Cloisters Cross for display in the newly rededicated cathedral and treasury, principally for cultural and educational purposes. Two painstakingly exact replicas were made in epoxy resin by the Met’s reproduction studio, headed by Ronald Street. I directed the project (Fig. 2.4). One replica is in Bury St Edmunds; the other was made available for scrutiny at Revisiting the Cloisters Cross: A One-Day Colloquium held at the Courtauld Institute of Art in London on 12 May 2023. Its surface is like that of a walrus tooth, and touching and handling it led to a better understanding of its ingenious construction, iconography, style, and inscriptions. The surfaces of the replicas are tinted to match the decorative patterns and inscriptions on the original Cross, which show evidence of early applications of waxy red and green pigments.3

For whom, and for what purpose, was this exceptional Cross created? After sixty years of study, these issues are still being investigated and debated. Let us begin with some key facts around the Met’s determination in 1962 to purchase the Cross that have not been previously acknowledged and then work backwards in time.

The Met’s Curatorial Acquisition Form was approved by the Purchase Committee on 18 October 1962, subject to the director’s approval. The Cross was eventually assigned the acquisition number 63.12, meaning it was the twelfth item purchased in 1963. The form is brief and says only the following: ‘Cross, Walrus ivory, Northern European, 12th century’. It is signed by Margaret B. Freeman, curator of the Cloisters, not by Thomas Hoving, associate curator, although it was his project. The acquisition form bluntly states, with no discursive analysis:

The feeling of the Department about the object can be summed up most accurately by quoting Dr. George Zarnecki, of the Warburg and Courtauld Institute, London, who was asked to expertise the cross for the British Museum: ‘The institution that acquires this cross can consider itself the most fortunate in the world’. [Included on the form is a note: ‘Prof. Kurt Weitzmann . . . stated: “I have no reservations as to its genuineness”’.]4

In June 1964, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin featured an article entitled ‘The Bury St. Edmunds Cross’, written by Hoving. In a prefatory note, James Rorimer, the Met’s director, said the Cross ‘was first called to our attention in 1956’ and was examined in September 1961 in Zurich by Hoving and Carmen Gómez-Moreno, assistant curator.5 Why the sudden change in the identity and origin of the Cross from simply ‘Northern European’ to ‘Bury St Edmunds’?

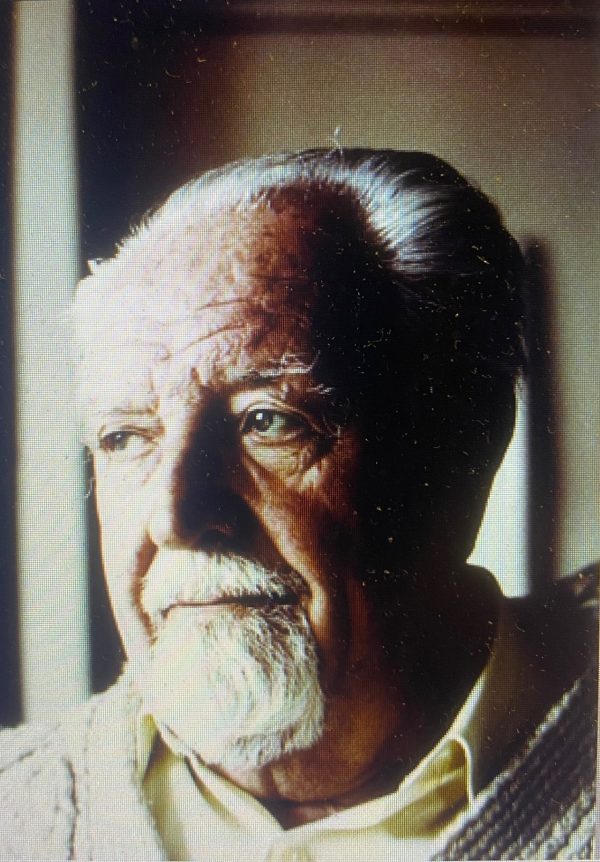

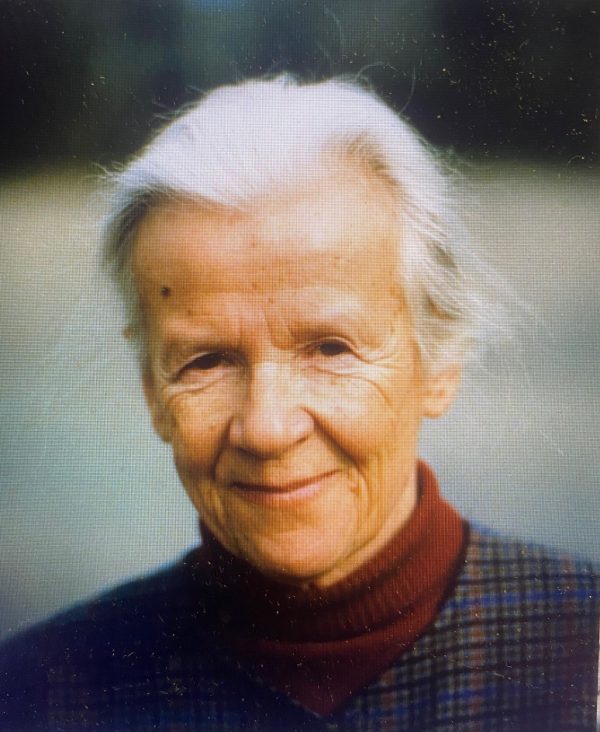

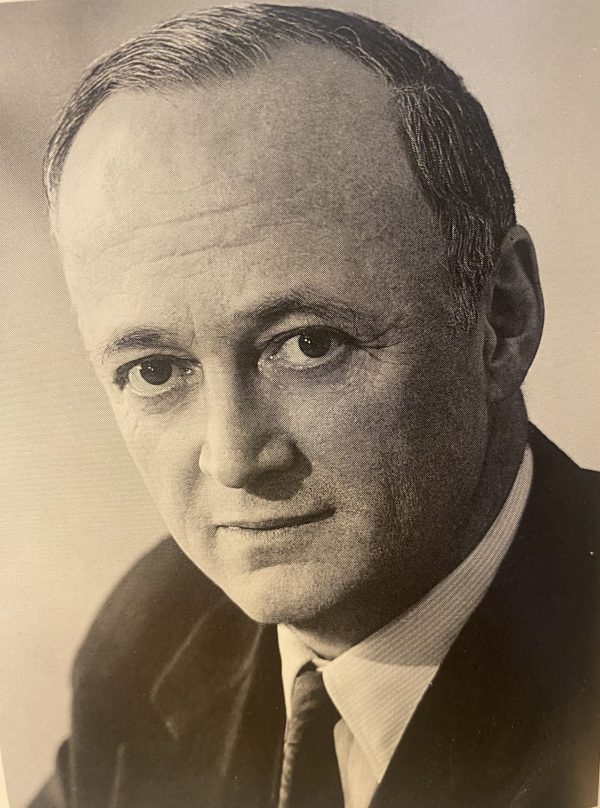

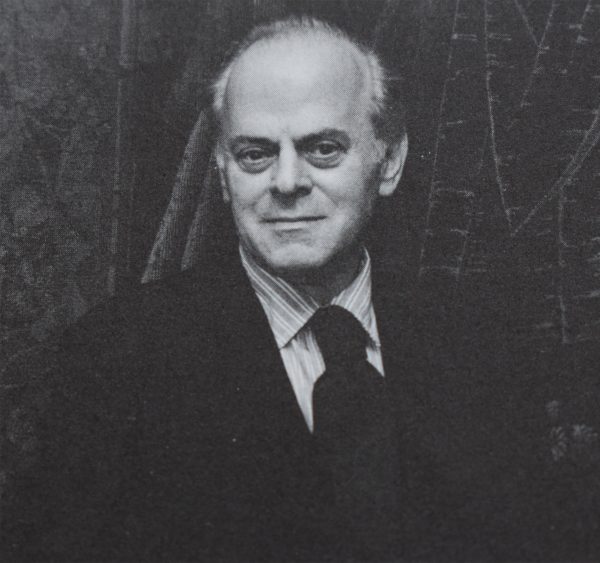

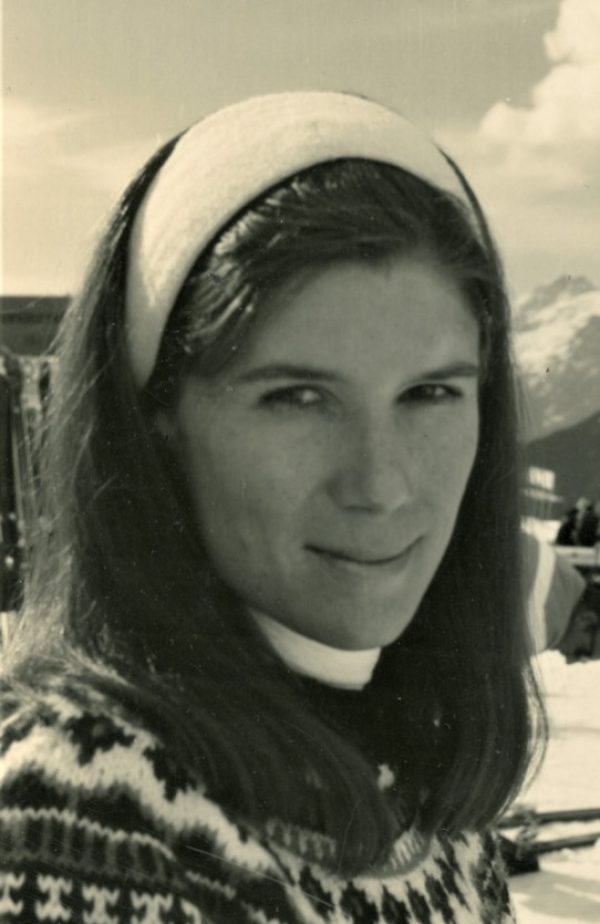

The main dramatis personae in the initial stages of the modern rediscovery of the Cross, its acquisition, and research pertaining to it are the following (Figs. 2.5–2.13): Ante Topić Mimara (1898–1987) (hereafter Topić, as he was generally known), who had the Cross for sale; Wiltrud Mersmann (1919–2022), Topić’s eventual wife; James Rorimer (1905–1966), curator in the Department of Medieval Art at the Cloisters (1929–55), and then director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1955–66); Carmen Gómez-Moreno (1914–2008), assistant curator in the Medieval Department of the Cloisters and later department head; Thomas Hoving (1931–2009), associate curator in the Medieval Department of the Cloisters and later director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1967–78); Harry Bober (1915–1988), Avalon Professor of the Humanities at the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, whom Rorimer and Hoving consulted; Margaret Freeman (1899–1980), curator of the Cloisters (1928) and head of the Cloisters (1955–65); Kay (Katherine) Serrell Rorimer (1908–2000), wife of James; and Sabrina Jane Longland, now Sabrina Harcourt-Smith (b. 1939), research assistant at the Cloisters after the acquisition of the Cross. With the help of these people, the search began for understanding the making, meaning, and identity of one of the most remarkable works of art to survive from the Middle Ages. Now, with a flood of publications appearing over the course of sixty years—at least 120 listings in the Met’s bibliography—we again try to make sense of the Cross. How did the quest for its origin really begin and develop?

In 1963, the Met’s director, Rorimer, recommended that Hoving show the Cross to Professor Bober of the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University. Bober suggested to Hoving that he look closely at the Bury Bible.6 Bober had his own personal photos of this Bible from the Warburg Institute in London.7 Hoving never acknowledged Bober’s role in understanding the Cross in any form, but it was to be fundamental for what followed.

In today’s predominantly secular world, issues of an artwork’s production, material, style, provenance, and place within a culture overwhelm its fundamental meaning and purpose, which is especially true of a great religious object like the Cloisters Cross. Its meaning and purpose were primarily simple and direct: ‘to prove that Jesus of Nazareth was God’s Anointed one—Messiah in Hebrew, Christos in Greek—and chosen to serve all who acknowledge Him as ‘King of Confessors”’.8 Confession is a way to one’s salvation. As a kind of private devotion, the maker and/or owner of the Cross was likely seeking his own redemption in the process. In essence, the Cross attempts to demonstrate, both visually and verbally, that the Old Testament confirms Jesus of Nazareth as the Christ. While the means of seeking one’s salvation are major theological questions, they suggest that the Cross’ singularity, and the cohesiveness of its images and texts, point to one maker/designer. This, however, does not rule out a more public and occasional ceremonial usage for the Cross.

I would like to address several overlapping scenarios of provenance for the Cross. Admittedly, these are speculations and remain shadowy, but they also contain some demonstrable realities.

First Scenario

Josef H. Kugler (1920–1994), a Hungarian engineer who had emigrated to the United States in the 1950s, told Hoving in late 1981 that he saw the Cross around 1930. Kugler had just read the December 1981 issue of Reader’s Digest, a popular magazine, that contained an excerpt from Hoving’s new book King of Confessors.9 On 16 April 1986, I interviewed Josef Kugler with Elizabeth Parker (a professor at Fordham University and my co-author on a publication on the Cloisters Cross) when he was visiting family near Philadelphia, coming from his home in Carlisle, Ohio. He told us that he saw the Cross circa 1932 or 1933 at the age of twelve when he visited a Father Veit at the Cistercian monastery at Zirc with his grandfather. Kugler said that Father Veit had said that pieces of the cross were found with ‘junk’ in an armoire he had acquired from the Premonstratensian abbey in Zsámbék and only later taken to Zirc. Kugler recalled that the Cross was thought to have been cursed. (An inscription on the Cross reads: ‘Maledictus omnis qui pendet in ligno’ [Cursed is every one that hangeth on a tree; Galatians 3:13].) He said that the papers in which the multiple pieces of the cross were wrapped within the armoire indicated that it ‘was taken on a crusade by a soldier—identified only as G—who was bringing it to Jerusalem to be blessed’.10

Kugler told us that he was later drafted into the German army; he was in the Fifth Panzer Division during the Second World War and saw action at the siege of Stalingrad and at the Battle of the Bulge. Can his scenario be trusted? Here was one person who had the strong likelihood of having seen the Cross in modern times, but we never dreamed of asking him the more challenging questions of what he really did during the war and in its aftermath, and whether he then also later returned to Zirc. He may have remembered or learned of the Cistercians’ dire predicament after the war, when the Soviets closed the Zirc monastery in the autumn of 1950 and forced the monks’ departure. Indeed, it is known that some of the Cistercians of Zirc fled to Western Europe, but about a dozen eventually formed a new community called Our Lady of Dallas in Irving, Texas (1954–61). The abbey is today an active Cistercian centre. Attempts to pursue this scenario found no confirmation from the order in Texas and they never acknowledged any awareness of the Cross’ existence.11

This narrative is not unlike what Topić reputedly had told Hoving—that he found the Cross in a monastery in 1938 and persuaded the monks to sell it—but again, Hoving also indicated that this happened ‘around 1947/48’.12 Nonetheless, Kugler seemed to be telling us honestly that he remembered the Cross from his youth at the Hungarian monastery at Zirc. Is there independent confirmation that Kugler saw the Cross? Yes, I think his recollection that the Cross was in multiple pieces was not generally known or published until images were included in our 1994 monograph. Topić reportedly showed a single piece of the Cross to Erich Meyer, curator of the Schloss Museum, Berlin, in 1938. Again, Hermann Schnitzler in Cologne, director of the Schnütgen Museum, circa 1950/1951, may also have seen the upper portion of the Cross.13 Hoving rarely spoke about this fundamental fact that the Cross was in multiple (five) pieces or of its particular method of construction.14

Second Scenario

There is another scenario: that the entire Cross, or portions thereof, were associated with the Central Collecting Point in Munich and there became available to Topić. This may have happened with the aid of Mersmann in her secretarial position at the Central Collecting Point, starting in March 1946 and ending in June 1949 (Fig. 2.14).15 She may also have learned of other works, like the Cross, that were not actually there. This was subtly suggested by Mersmann herself in her letter to me in 1987: ‘The Cross was with a clerical community; they wanted to sell [it] and start a new life in Western Europe; Topić promised them [that he would] not reveal this’.16 The reason Mersmann said no more about its provenance may confirm what Topić apparently promised Hoving: that he would leave a notice at his death concerning its provenance, but to our knowledge, Topić never did this. Did these events take place in the 1930s or the late 1940s, or in 1950 or 1955? Was this ‘clerical community’ that Mersmann mentioned in fact the Cistercian abbey at Zirc—founded in 1182 by King Béla III of Hungary on royal farmland in the Bakony Forest (see below)—where Kugler said he saw the Cross?

Does this information constitute a verifiable modern provenance for the Cross in Hungary? Again, I think yes, because linking this scenario to that of the fate of the abbey of Zirc produces the strong possibility that Mersmann was correct in saying that Topić got the Cross, or parts thereof, around 1950 or before, and could not reveal its origin.17 Ideally, historical verification of the provenance of the Cross would be based on independent confirmation from multiple sources. In my opinion, and based on the information outlined here, there is a high degree of probability that the Cross, in modern times, came from Zirc or another monastic foundation in the region, such as Zsámbék. After all, Topić’s base was in Zagreb, and Zirc is geographically within two hundred kilometres as the crow flies. So, together, the scenarios of Topić and Kugler are plausible and have some consistency.

Third Scenario

Among other possibilities, there is also a convenient medieval historical link between England and Hungary that may support an English origin for the Cross. In 1160, Thomas Becket, then chancellor of England, negotiated nuptials for Margaret of France, infant daughter of Louis VII of France and Constance of Castille, to Henry, the eldest son of Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine. Prince Henry was five and a half and Margaret was two. They were married in Winchester on 2 November 1160. When Henry died in France in 1183, Margaret, now age twenty-five, immediately became an eligible widow. Margaret was then betrothed to Béla III of Hungary in August 1186 by her brother, Philip II of France, known as Philip Augustus. This was a Capetian/Hungarian political manoeuvre of alliances. Margaret went to reside in Esztergom and was accompanied there by a retinue of French and English knights. She took ‘treasure’ with her, likely her dowry.18 A nearby chapel in Esztergom was dedicated to Thomas Becket in homage to him, as the recently martyred archbishop of Canterbury, and to her English connections. There is also an association with Zirc. In 1182, Béla III founded a Benedictine monastery at Zirc which eventually became Cistercian.19 In April 1196, Béla died and his widow Margaret accompanied the Hungarian crusade to the Holy Land where she died at Acre in September 1197. She was buried in the city of Tyre. Overall, this scenario is more reflective of the political dynamics of the period than specific documentation thereof or the movement of explicit works of art.20

Where Did the Cross Originally Come From?

If the Cross was created somewhere in northern Europe and then taken to Hungary, what were the circumstances? It is made of multiple pieces of walrus ivory, making it both compact and portable. Its ingenious interlocking elements aided in ensuring its survival. I would maintain that the linking of its principal elements reflects carpentry knowledge utilizing a kind of double-lap join method that is more typical of shipbuilding technology evolving from the age of the Vikings.21 The considerable amount of walrus ivory required to create the Cross demanded the resources of a major and wealthy ecclesiastical institution, either monastic or episcopal. One cannot also rule out a royal patron.22 The walrus material could come from anywhere around the North Atlantic, not necessarily from Nordic lands or Greenland.23 For example, in 1521 Albrecht Dürer sketched a walrus that he noted in the inscription came from the Netherlands sea.24

When first displayed at the Cloisters, following Hoving’s publication, the Cross was labelled ‘The Bury St. Edmunds’ Cross’. In our 1994 monograph it was called ‘English’ and we recommended that site as likely. Presently, the Cloisters Cross is called ‘British’, though this term is more valid only after 1603 and the accession of James I.25 Over the last sixty years, a variety of geographic (and temporal) attributions have been put forward for the Cross: Anglo-Saxon England, Romanesque England, Bury St Edmunds, St Albans, or Winchester. Likewise, there are various Continental advocates: the English Channel area, Belgium and the Meuse Valley, Abbey of Le Parc (near Louvain), Liège, the Rhineland, Hildesheim and Lower Saxony, and Denmark and Ribe, or just ‘the North’.26

The clear problem for any geographic placement of the Cross has been the challenge of having all the following criteria function in concert for a more secure origin/location: the material, the figure style and composition of the subjects, and the iconographic peculiarities and the inscriptions. A single stylistic or type comparison is unlikely to be compelling. Therefore, like the question of provenance, the artistic and geographic origins of the Cross have, after sixty years, seen the ‘net’ being cast ever wider. Each position is rich and provocative, but all have gaps. From a visual or stylistic point of view, Erwin Panofsky’s witty and true maxim that ‘if one wants to prove their point, do not illustrate it!’—quipped in lectures and seminars—should be kept in mind. Nevertheless, it may be fruitful to review some geographic options, at least those for which artistic, historical, and cultural placements have been made.

England

The Met initially assigned the Cross to Bury St Edmunds and to the hand, or style, of Master Hugo. The ‘Hugo style’ was innovative. However, his origins as a professional artist are debated by scholars.27 The reason favoured by many for an English attribution (and possibly Bury St Edmunds) is that England held, or appeared to hold, the weight of a higher degree of probability when considering all the factors of where, when, who, and why that ideally should function in unison. A key question is: Do style, relief technique, and composition surpass iconographic themes and inscriptions and texts?

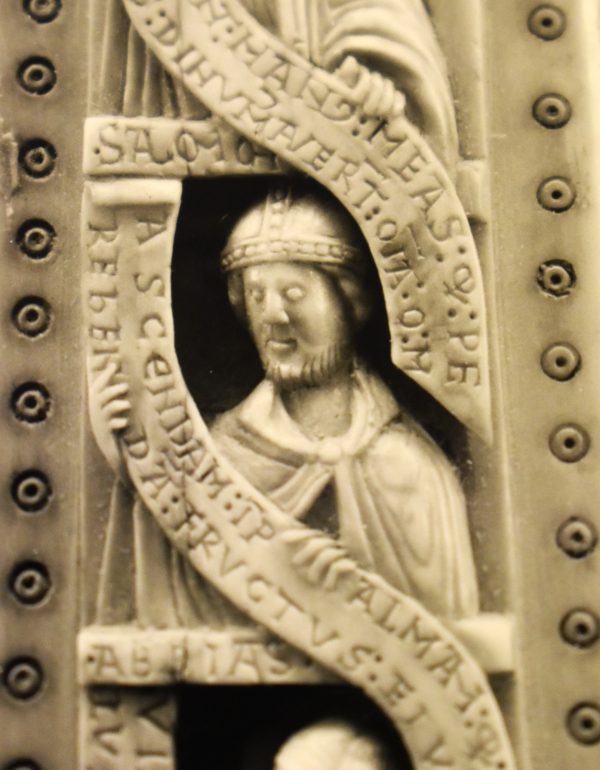

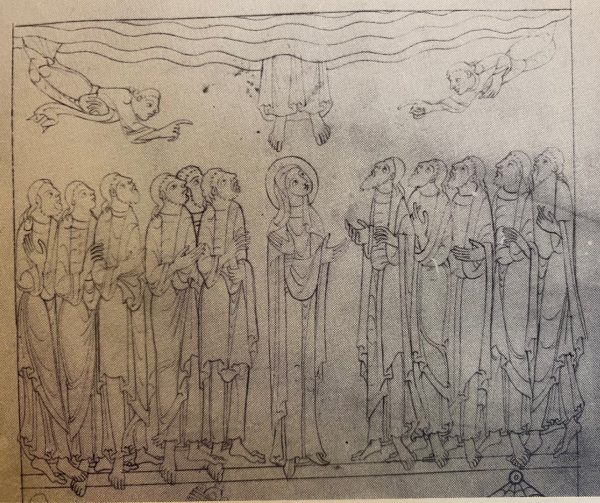

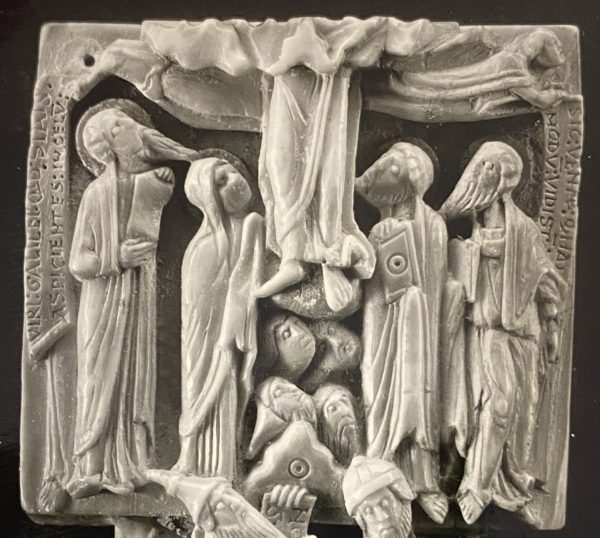

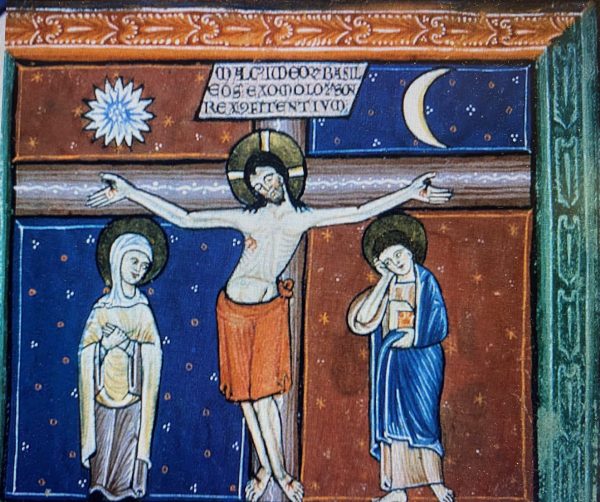

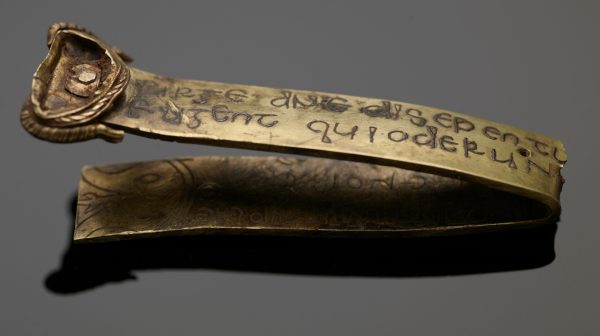

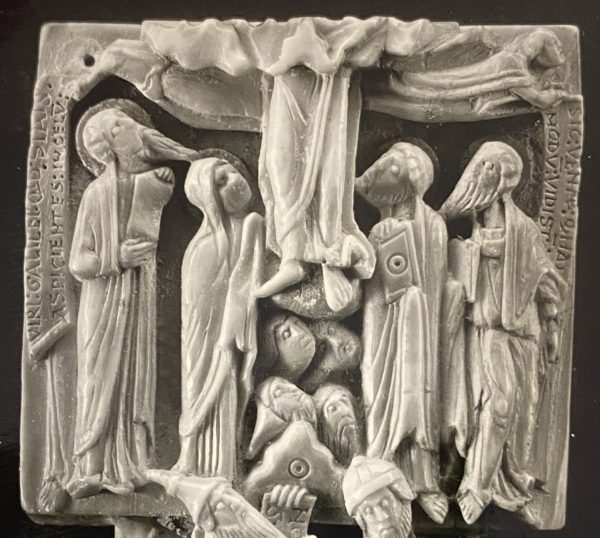

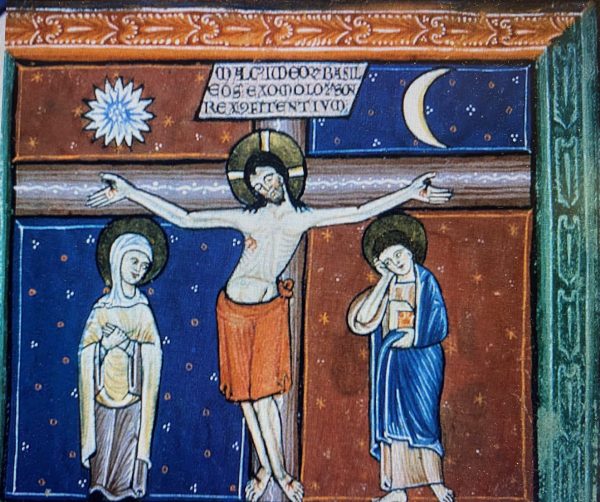

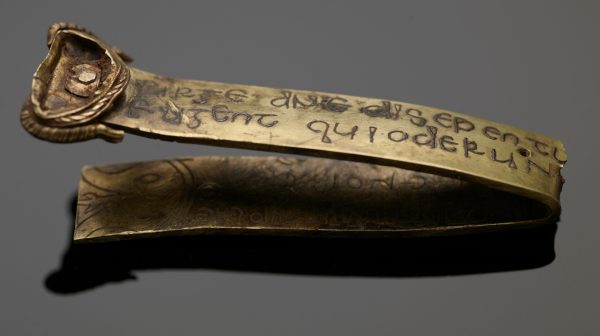

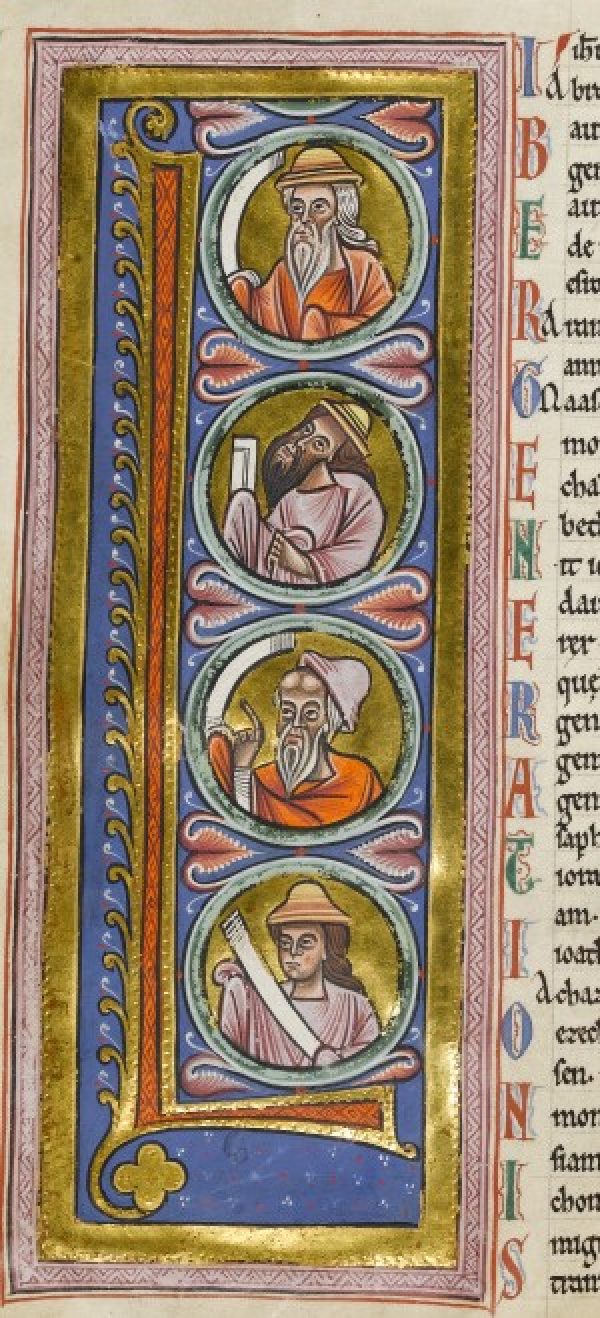

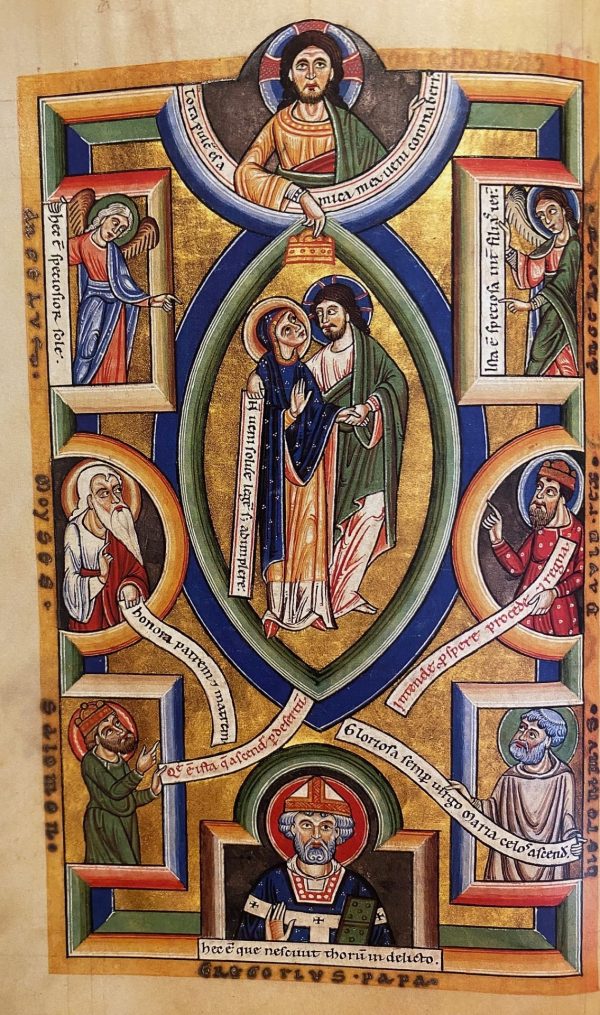

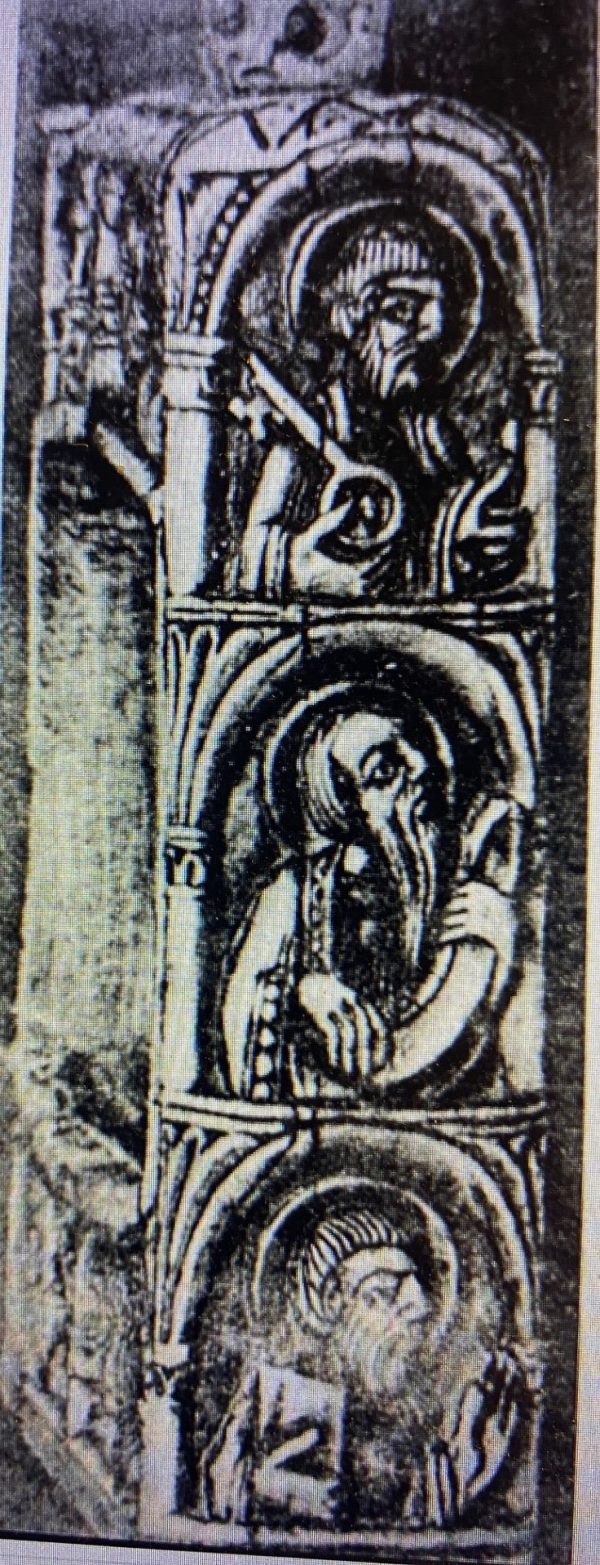

The case for Hugo’s involvement was based on multiple factors, mostly stylistic and compositional: his making of the great Bury Bible for Sacrist Hervey (ca. 1125–36) (Figs. 2.15 and 2.16), the double doors of the abbey that were carved (not cast) by the hands of Master Hugo (insculpti digitis), a bell made for Bury in the time of Anselm (1121–48), and a cross for the choir with Mary and John that was ‘carved incomparably’ in the time of Sacrist Elias (1148–56).28 Hugo also likely made the seal matrix for the abbey—small in scale and of high quality—that appears to be related to figural forms on the Cross (Figs. 2.17 and 2.18).29 Hugo was well travelled. For example, his distinct figure style was reflected directly in the apostles depicted on the lead baptismal font at Walton-on-the-Hill.30 Additionally, excavated figurative sculptures at Bury St Edmunds and at St Albans Abbey, albeit of vastly different scales and materials, have been compared (Figs. 2.19 and 2.20). The composition of the Cross’ Ascension scene with Christ disappearing into a cloud—with wingless angels—is a form often considered initially English, with numerous examples, such as the Pembroke College Gospels or the Hunterian Psalter; the form was also prevalent at the same time on the Continent (Figs. 2.21 and 2.22).31 The rare Rex confessorum titulus on the Cross is echoed pictorially elsewhere only in the early thirteenth-century Arundel Psalter as Rex confitentium—and seems to be a further relevant English parallel (Figs. 2.23 and 2.24).32 In a similar vein, the phenomenon of ‘talking crosses’ is apparently part of a long tradition in England and Ireland rather than on the Continent. One of the earliest examples may be the seventh-century gold cross with inscriptions from the biblical book of Numbers (part of the Staffordshire hoard discovered in 2009) (Fig. 2.25); others include the Ruthwell cross and the Angel cross (Otley, Yorkshire).33 The most visible large inscriptions on the Cross, Cham ridet and terra tremit, both incised and inlaid with green, waxy pigment, are difficult to read unless the Cross is rotated and in good light. Both inscriptions are special or unique—such as being formerly painted in the choir at Bury St Edmunds—and are not found elsewhere in Europe, except as a variant, such as at the Abbey of Saint-Denis and later in the Biblia pauperum, as already noted by Mersmann and Longland.34 Thus, they collectively may, or may not, point to a particular centre for the Cross’ making in England.

The Continent

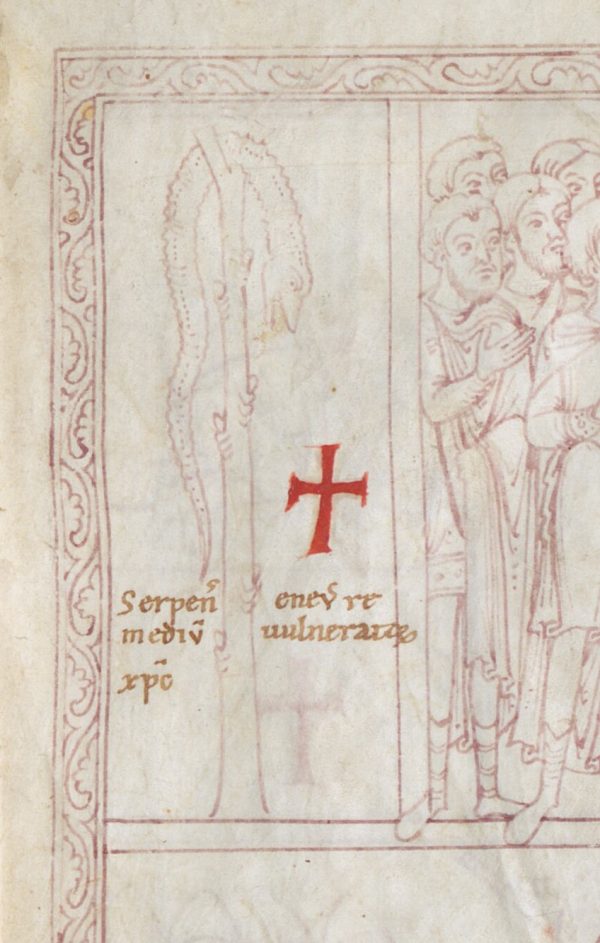

Nevertheless, from an early date, and after the Met’s acquisition of the Cross, other geographic attributions were proposed by many scholars: the English Channel area, the Low Countries—home to the Abbey of Le Parc in Louvain, for example (Fig. 2.26)—and the Rhineland and Saxony.35 For the most part, these scholars focused on style and compositional links rather than iconographic issues. For example, the Stammheim Missal, produced in Hildesheim, has figures with jutting beards and holding scrolls (Fig. 2.27).36 Similarly, other Continental manuscripts contain Old Testament prophets clutching scrolls. This extends to ivory carvings and sculptures that are not unlike the prophets on the Cross (Figs. 2.28 and 2.29).37 Thus, many of these visual aspects may be more universal than initially thought. In a similar vein, the particular Brazen Serpent composition or type of form was found on the Continent at about the same moment as the Cross, as seen, for example, in a manuscript of the Dialogus de laudibus scantae crucis from Prüfening Abbey in Regensburg (Figures 2.30 and 2.31).38

One can further expand the possibilities to more Northern geographic attributions for the Cross. Before the Met’s 1970 exhibition The Year 1200, the possibility that the Oslo Corpus was originally part of the Cross was raised, first by Martin Blindheim, leading the Met to bring them together on that occasion (Figs. 2.32 and 2.33).39 Ultimately, this also returns to T. A. Heslop’s earlier and current position.40 To reconstruct and to complete the Oslo Corpus anatomically, using the Met’s replica, the initial result appeared to demonstrate a steep angle for the arms and a single nail for the feet. This must also be reconsidered but still may not rule out the possibility of the Oslo Corpus being an early replacement for the original, now lost corpus.41

Conclusions

Over the years, the understanding of the Cloisters Cross has gone through what is perhaps best characterized as the Hegelian process of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis and is likely to continue to evolve. The Met’s preliminary attribution of the Cross to ‘Northern Europe’ may, in retrospect, have been a wise and prescient decision, most plausibly by Rorimer, who, as the museum’s director, was ultimately responsible for its acquisition and thus making it available for future generations to enjoy. The colloquium Revisiting the Cloisters Cross offered yet more new perspectives on and possibilities for understanding one of the greatest surviving portable masterpieces of the Middle Ages.

Citations

[1] My thanks to the organizers of Revisiting the Cloisters Cross: A One-Day Colloquium, held on 12 May 2023 at the Courtauld Institute of Art in London, for the opportunity to reflect on the Cross again after a life of being a museum curator and the Cross always being present. I was happily aided by Elizabeth Parker, who offered sensible comments and clear recollections. The Met’s selective bibliography on the Cloisters Cross is available in its The Museum System (TMS) collection search, under its accession number 63.12. This article is dedicated to Libby Parker to recognize her lifelong devotion to the study of the art of the Middle Ages.

[2] Today the Cross survives in five pieces. The lower shaft, though broken at the base, is the longest (34.4 cm) and is made of a single walrus incisor tooth; the normal size of such a tooth for a male walrus is a maximum of circa 50 cm. The main cross arm is 25 cm, with the two end terminals secured to it with a flat, interior tang. The upper shaft is 21 cm, including the interior tongue.

[3] In September 2004 one replica was presented to St Edmundsbury Cathedral at a sung Eucharist. Later, a musical drama composed by Judith Bingham, The Ivory Tree, was presented. A commercial version of the Cloisters Cross is still available from the Met; however, it is of significantly lower quality and made in one piece. On the construction of the Cloisters Cross, see Elizabeth C. Parker and Charles T. Little, The Cloisters Cross: Its Art and Meaning (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1994), 22–28.

[4] Curatorial Acquisition Form, 18 October 1962, Acquisition Papers, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

[5] Thomas P. Hoving and James J. Rorimer, ‘The Bury St. Edmunds Cross’, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 22, no. 10 (1964): 317.

[6] Bury Bible, MS 00211, Corpus Christi College, Cambridge.

[7] Bober’s photographs are in the Met’s files. Indeed, Bober’s son, Jonathan, former Mellon Curator at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, confirmed this in an email to the author (3 March 2023): ‘As you certainly know, Harry did resent that he had made the essential observations and connections, but that the showman Hoving claimed discovery, research, and all’. Additionally, Elizabeth Parker wrote a personal letter to Hoving on 27 January 1976 (author’s copy), saying ‘Professor Bober once mentioned in a lecture having discussed the stylistic parallels to the Bury Bible with you when you were writing your first article, and the connections have always seemed most compelling’.

[8] Katherine Rorimer wrote a 161-page unpublished monograph titled ‘Thus Spake Obadiah’. The manuscript is in the Cloisters archive, gifted by her daughter, Anne, in May 2004. It chronicles in detail the problems of Thomas Hoving’s book, King of the Confessors (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1981). See Katherine Rorimer, introduction to ‘Thus Spake Obadiah’ (unpublished manuscript), p. 1, Cloisters Cross Research Papers, subseries IIC: KSR Manuscript Drafts, folder 15, box 11, Cloisters Library and Archives, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Her learned, insightful, and unique perspective is essential to a better understanding of the Cross and its place in medieval scholarship. On Harry Bober, see Rorimer, ‘Thus Spake Obadiah’, 140.

[9] Thomas Hoving, ‘Quest for the Lost Cross’, Reader’s Digest, December 1981, 242–88.

[10] Josef Kugler, interview by Charles T. Little and Elizabeth Parker, 16 April 1986, held in a restaurant in a hotel near Philadelphia.

[11] See Abbot Anselm Nagy to Janos Adam, 17 October 1987 (regarding Father Veit [i.e., the Cistercian Father Tibor Humpfner (1885–1966]), Charles T. Little and Elizabeth C. Parker Personal Papers. Elizabeth Parker said this was John (Janos) Adam (d. 2010), a Hungarian Jesuit and philosophy professor at Fordham University, who wrote to him on behalf of Parker. See memo from Elizabeth Parker to Father Janos Adam, 12 April 1986. Abbot Nagy, of the Texas community, replied, saying that he ‘doubted [the Cross] was ever in the hands of a Cistercian Father’. See Abbot Anselm Nagy to Janos Adam, 10 November 1987, Charles T. Little and Elizabeth C. Parker Personal Papers. Given the Cistercians’ extremely precarious situation in Zirc, their total silence is understandable. At the time of our interview with Josef Kugler, our discussions with him were filled with wonder and eagerness but also naïveté. See also Parker and Little, Cloisters Cross, 14–16.

[12] Thomas Hoving, King of the Confessors: A New Appraisal (Christchurch, Le Vergne: Cybereditions, 2001), 266. However, Hoving, in correspondence with John Beckwith around the latter’s exhibition of 1974 at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, says that ‘Topić found the cross around 1947–48’. See Thomas Hoving to John Beckwith, 22 April 1974, Thomas Hoving records (bulk 1967–1977), series IV, Correspondence, Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. For Beckwith’s exhibition, see John Beckwith, ed., Ivory Carvings in Early Medieval England, 700–1200 (London: Victoria and Albert Museum, Arts Council, 1974). There is another narrative in Thomas Hoving, The Chase, The Capture: Collecting at the Metropolitan (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1975), 70–96. The prologue of Hoving’s King of the Confessors sets the stage for his approach to the Cross by quoting Michel de Montaigne: ‘The excitement of the chase is properly our quarry’. See Hoving, King of the Confessors [1981], 18.

[13] See Hoving, King of the Confessors [1981], 207–9 (regarding Schnitzler), 210–13 (regarding Meyer). See also Parker and Little, 1994, 15 and n3.

[14] See Hoving, King of the Confessors [1981], 212 (quoting Topić).

[15] The following account is at variance with the chronology of Hoving’s colourful account. I was introduced to Mersmann by Florentine Mütherich (1915–2015), whom I had known since the early 1970s. Mütherich had known Mersmann in school in Berlin, where Mütherich received her PhD. Mersmann received hers from the University of Vienna. See Craig Hugh Smyth, The Central Art Collecting Point in Munich, Veröffentlichungen des Zentralinstituts für Kunstgeschichte in München 63 (Passau: Dietmar Klinger, 2022), 42, fig. 20 (photograph). The photograph shows Mersmann (later a professor at the University of Salzburg) with Wolfgang Lotz (later professor at the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, and then director of the Biblioteca Hertziana, Rome) and Theodor Müller (curator and then director at the Bayerische Nationalmuseum, Munich), among others, at the Central Collecting Point in March 1946. Rorimer was central to establishing the Central Collecting Point in Munich in 1945. See James J. Rorimer, Louis Rorimer, and Anne Rorimer, Monuments Man: The Mission to Save Vermeers, Rembrandts, Da Vincis, and More from the Nazis’ Grasp, new ed. (New York: Rizzoli Electa, 2022), 294–95. Craig Smyth (1915–2006) was in charge from June 1945 to March 1946.

[16] Wiltrud Mersmann to Charles T. Little, 17 September 1987 (author’s copy). Mersmann’s son, Nikolaus Topić-Matutin, confirmed this statement to me in 2010 and noted that his recollection of the Cross goes back to around 1955.

[17] Elizabeth Parker believed that Topić wanted to keep protecting the Cistercians from whom he got the Cross and maintained this source with silence. This approach is not unlike that of the Monuments Men, who never talked about what they did during those years.

[18] See Marta Pellérdi, ‘Margaret of France: Conciliator Queen of England and Hungary’, in Norman to Early Plantagenet Consorts: Power, Influence, and Dynasty, ed. Aidan Norrie et al. (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2023), 139–57.

[19] See Konstantin Horváth, Zirc Története [History of Zirc], Zirci Könyvek 1 (Veszprém: Egyházmegyei Ny., 1930).

[20] In a similar way, the marriage of Matilda of England to Henry the Lion of Saxony in 1168 created other artistic interchanges and potential scenarios. On this, see Cecily Hennessy’s essay in this volume.

[21] In general, see Gareth Williams, The Viking Ship (London: British Museum Press, 2014).

[22] See T. A. Heslop’s essay in this volume.

[23] Given newer DNA and C-14 analytical methods of investigation, an updated initiative would be desirable. See Robyn Barrow’s essay in this volume; and Robyn Barrow, ‘Gunhild’s Cross and the North Atlantic Trade Sphere’, The Medieval Globe 7, no. 1 (2021): 53–75.

[24] Albrecht Dürer, untitled drawing of the head of a walrus, 1521, SL,5261.167, British Museum, London. In translation, Dürer’s note says: ‘the animal represented here of which I portrayed the head was caught in the Netherlands sea’.

[25] For example, see James Shapiro, 1606: William Shakespeare and the Year of Lear (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2015), 40–42.

[26] See especially Elizabeth C. Parker, ‘Editing the “Cloisters Cross”’, Gesta 45, no. 2 (2006): 147–60, for an assessment of the Cross’ literature prior to 2007. See also, among others, Denis Blomfield-Smith, The Walrus Said: A Long Silence Is Broken (Lewes: Book Guild, 2004); and Stephen Gardner’s unpublished essay for a Princeton University seminar on iconography for Professor Rosalie Green, fall 1971, presented as a Frick symposium talk (28 April 1973) informally titled ‘Resurrection Plaque of the Cloister’s Cross’. On the latter, see Cecily Hennessy’s essay in this volume.

[27] Was Master Hugo similar to the artist Nivardus, active around 1000, who came from Milan and was working at Abbey de Fleury (St-Benoit-sur-Loire)? Or was he like Engelram, whose Germanic name is a surprise for an artist active in Castile-León and at San Millán de la Cogolla (La Rioja)? Or was he like Tuotilo, the celebrated artist at Sankt Gallen around 900, who worked in multiple media—painting, gold, and ivory—and, although of monastic fame, was celebrated enough to travel for commissions in Metz and Mainz?

[28] Elizabeth C. Parker, ‘Master Hugo as Sculptor: A Source for the Style of the Bury Bible’, Gesta 20, no. 1 (1981): 100 and n18.

[29] Parker, ‘Master Hugo as Sculptor: A Source for the Style of the Bury Bible’. For another view, see Blomfield-Smith, The Walrus Said.

[30] See, among others, Parker, ‘Editing the “Cloisters Cross”’; Rainer Kahsnitz, Goldschmidt Addenda: Nachträge zu den Bänden I–IV des Elfenbeincorpus von Adolph Goldschmidt, Berlin 1914–1926, Sonderucke aus der Zeitschrift des Deutschen Verein für Kunstwissenschaft 68, 72/73 (Berlin: Deutscher Verlag für Kunstwissenschaft, 2022), no. 155, 52–61; Rodney Thompson, ‘The Bury Bible: Further Thoughts’, in Tributes to Nigel Morgan: Contexts of Medieval Art; Images, Objects and Ideas, ed. Julian M. Luxford and M. A. Michael (London: Harvey Miller, 2010), 175–81; and George Zarnecki, English Romanesque Lead Sculpture: Lead Fonts of the Twelfth Century (New York: Philosophical Library, 1957), 7, 28–29.

[31] Pembroke College Gospels, MS 12, fol. 5v, Pembroke College, Cambridge; and Hunterian Psalter, MS Hunter 229, fol. 14, University Library, Glasglow. See also Parker and Little, The Cloisters Cross, figs. 65 and 66.

[32] See The Book of Psalms, Psalter of the Virgin Mary, and Little Office of the Virgin Mary, MS Arundel 157, fol. 10v, British Library, London. See also, for example, Sabrina Longland, ‘The “Bury St. Edmunds Cross”: Its Exceptional Place in English Twelfth-Century Art’, The Connoisseur 172 (1969): fig. 12.

[33] See Chris Fern, Tania Dickinson, and Leslie Webster, eds., The Staffordshire Hoard: An Anglo-Saxon Treasure (London: Society of Antiquaries, 2019), 103. See also Wiltrud Mersmann, ‘Das Elfenbeinkreuz der Sammlung Topić-Mimara’, Wallraf-Richartz-Jahrbuch 25 (1963): fig. 84 (a lost ivory reliquary with Apostles, possibly having painted inscriptions) and figs. 85–86 (the ninth-century Angel cross).

[34] On Bury St Edmunds, see Sabrina Longland, ‘A Literary Aspect of the Bury St. Edmunds Cross’, Metropolitan Museum of Art Journal, 2, 1969, 46–74. See also Mersmann, ‘Das Elfenbeinkreuz’, 8n10.

[35] See Parker, ‘Editing the “Cloisters Cross”’; and the Met’s bibliography under 63.12 on the museum’s website.

[36] Stammheim Missal, MS 64, J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. See the facsimile edition of Elizabeth C. Teviotdale et al., Das Stammheimer Missale/The Stammheim Missal (Lucerne: Quaternio Verlag, 2020).

[37] This is already noted in Mersmann, ‘Das Elfenbeinkreuz’, fig. 84; and Neil Stratford, ‘The Cloisters Cross’, The Burlington Magazine 156, no. 1336 (2014): 464. See also John Munns, ‘Relocating the Cloisters Cross’, The Burlington Magazine 155, no. 1323 (2013): 381–83.

[38] Dialogus de laudibus scantae crucis, clm 14159, fol. 3, Staatsbliothek, Munich. See Ursula Graepler-Diehl, ‘Eine Zeichnung des 11. Jahrhunderts im Sangalleensis 342’, in Studien zur Buchmalerei und Goldschmiedekunst des Mittelalters: Festschrift für Karl Hermann Usener zum 60. Geburstag am 19. August 1965, ed. Karl Hermann Usener and Frieda Dettweiler (Marburg: Verlag des kunstgeschichtlichen Seminars der Universität, 1967), 175, fig. 8.

[39]See Blindheim’s initial observations in Martin Blindheim, ‘En romansk Kristus-figur av Hvalrosstann’, in Kunstindustrimuseet i Oslo Årbok, 1969 (Oslo: Kunstindustrimuseet, 1968–69), 22–32; and Martin Blindheim, ‘Scandinavian Art and Its Relations with European Art around 1200’, in The Year 1200: A Symposium, ed. Konrad Hoffmann (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1975), 429–68, esp. 434. See also Tage Christiansen, ‘Ivories: Authenticity and Relationships’, Acta Archaeologica 46 (1975): 119–33. Christiansen also states that if the Oslo Corpus goes with the Cross, then both ‘might once have been Danish property’; see Christiansen, ‘Ivories’, 125. Christiansen indicated that the so-called Caiaphas plaque, whose subject was initially identified by Kurt Weitzmann, represented ‘Christ before Pilate’; see Christiansen, ‘Ivories’, 125.

[40] See T. A. Heslop’s essay in this volume.

[41] For example, Willibald Sauerländer, ‘“The Year 1200,” a Centennial Exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, February 12–May 10, 1970’, The Art Bulletin 53, no. 4 (1971): 512; Christiansen, ‘Ivories’; and T. A. Heslop’s essay in this volume.