T. A. Heslop

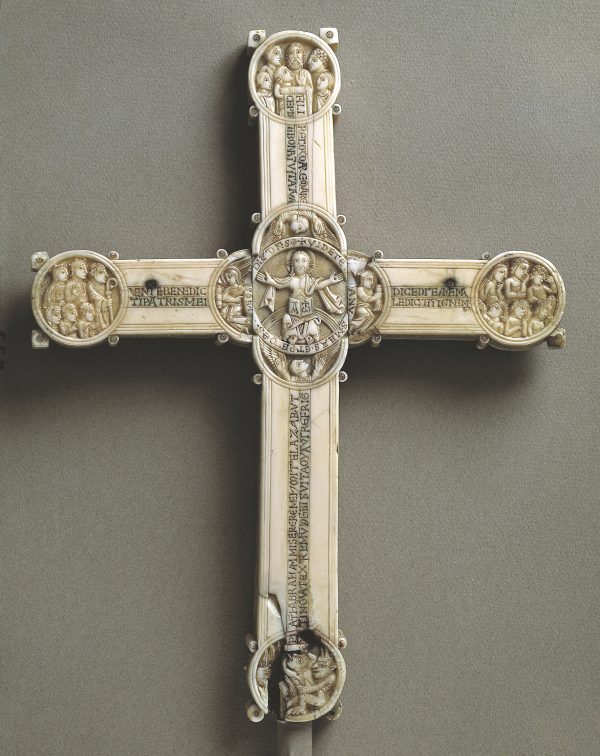

Nothing is known about the history of the Cloisters Cross during the first 750 years or so of its existence.1 Its likely origins in northern Europe are suggested by its material, walrus ivory, and its style has generally been perceived as High Romanesque of a type developed across the regions around the North Sea. The complexity of the Cross’ construction, the intricacy of its figural sculpture, and the plethora of inscriptions on an object not quite two feet high offer an abundance of material for analysis, but this has not resulted in a widely accepted attribution or understanding of its character. I first became interested in the Cross over fifty years ago and have puzzled over it intermittently ever since. What follows is an attempt to explain what I now think and why I think it. It is not a plea to be believed; rather it is a request for consideration (and criticism) of my methods, observations, and arguments, and an invitation to improve on them.

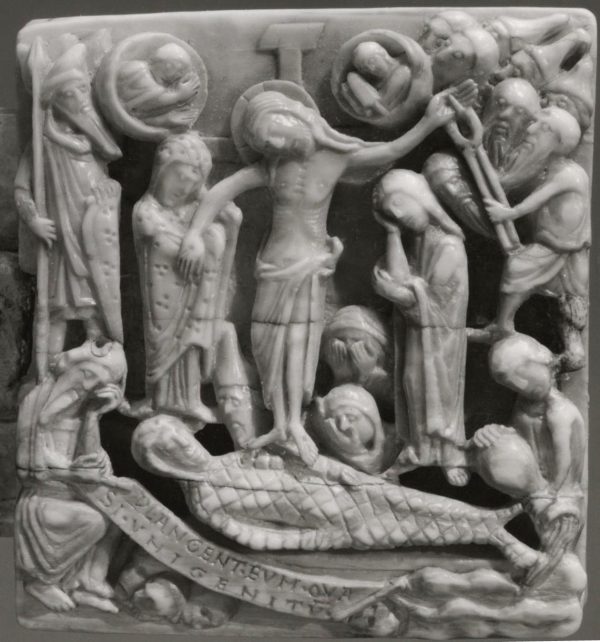

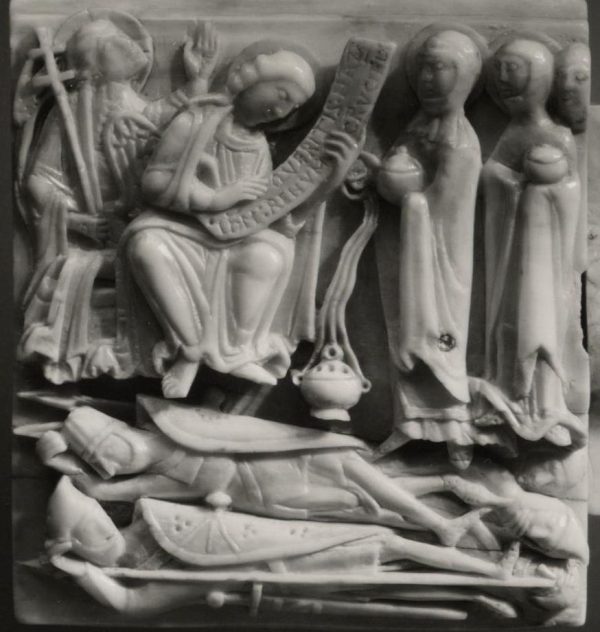

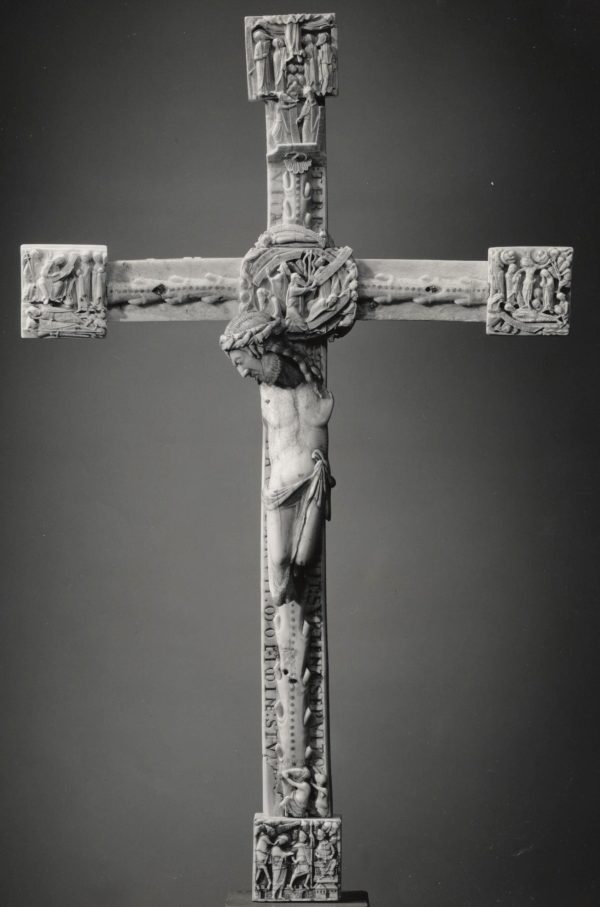

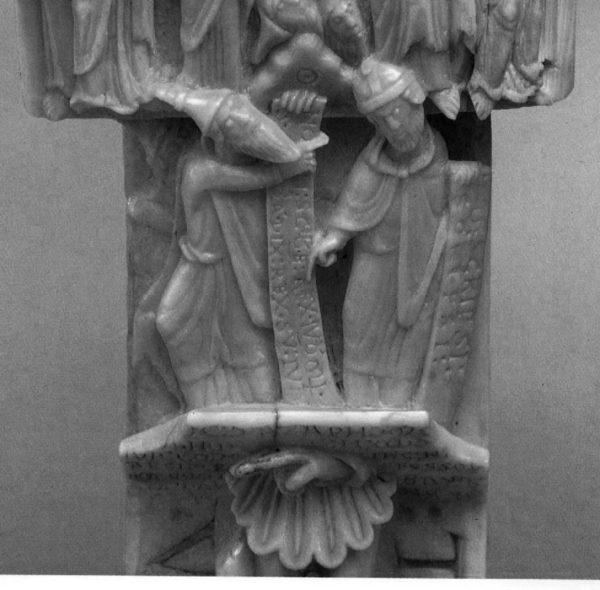

At the time of its purchase, the Cross was incomplete, missing its lower terminal and, more importantly, the central figure of Christ. To begin with the former, a remarkably appropriate walrus-ivory plaque showing Christ led before Pilate (Elizabeth Parker and Charles Little, following Bernice Jones, say Caiaphas) was identified as a ‘missing part’ and acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 1963 (63.127) (Fig. 7.1).2 Almost everything is in favour of the common origin of the plaque and the Cross. The plaque is the same size and has figures on the same scale as the other terminals, and has many characteristics found elsewhere on the Cross. These include an inscription, poses, and costume details, especially hats. As on the Cross itself, the tall, conical Jewish hat sometimes has a surrounding band at mid-height, whereas ‘Romans’ (with spears on the Cross’ Good Friday [Fig. 7.2] and Easter plaques [Fig. 7.3]) are shown with distinctive helmets or bonnets which are shorter and have a point at the front.3 Furthermore, like the Good Friday and Easter plaques, the Pilate plaque is a composite scene uniting discrete moments in the narrative so as to capture a sequence of events. The Good Friday plaque shows both the Deposition and the anointing of Christ’s body, and the Easter Sunday plaque combines Christ rising from the tomb and the visit of the Maries to the tomb. On the Pilate plaque, the first element shows a Jew with a tall, conical hat striking Christ and saying Prophetiza, as in the episode in Matthew (26:68) and Luke (22:64) when Christ stands before the Sanhedrin. Then (as in Mark and John) Christ is led into the presence of Pilate and his soldiers in the Praetorium. On the plaque, they are shown with ‘military’ bonnets and some hold spears. The combination of Jews (two more on the Pilate plaque look up towards Christ on the Cross) and Romans shows that both are party to Christ’s Passion, but the implication of his being already robed and crowned with thorns is that the Jews had so delivered him to Pilate. In John’s account, Christ’s transfer to imperial authority is followed by the scourging and the mocking by the Romans and the words (John 19:5), ‘Jesus then came out wearing the crown of thorns and the purple robe. Pilate said “behold the man”’ (ecce homo). That is significant because the reverse of the plaque (still missing) would have borne the symbol of Matthew, that is, a (winged) man. Hence this combination would echo the pairing of John’s eagle and Christ’s Ascension on the upper terminal of the Cloisters Cross, and the other standard pairings: Mark’s lion with the Resurrection and Luke’s ox with Christ’s sacrificial death on the lateral termini. The only problem in linking the Pilate plaque with the Cross is that their styles do not quite match: the plaque looks more classicising than late Romanesque in its figure poses and drapery folds. In my view, it is a copy made circa 1200 but based on the original to replace it when the lower terminal was damaged (the base of the Cross is cracked and fragmentary). The plaque was first recorded in 1920, in a sale at the Hôtel Drouot in Paris, and was subsequently in a private collection (Frau Fuld) in Berlin.4 Its earlier provenance is unknown.

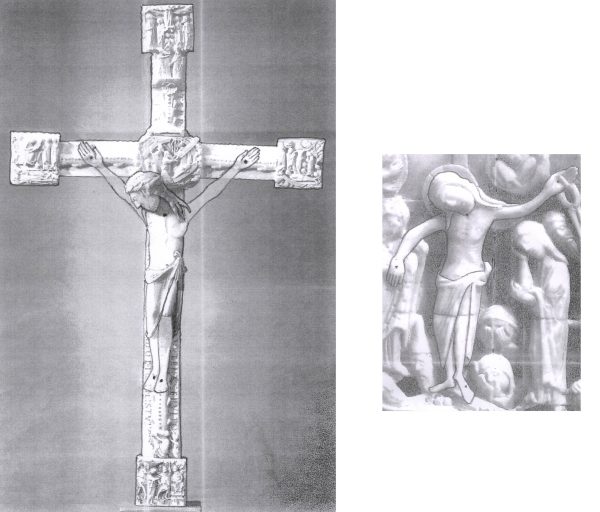

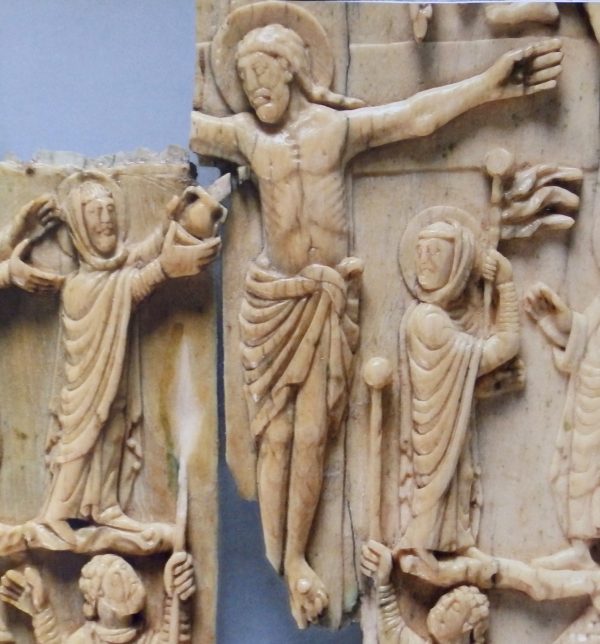

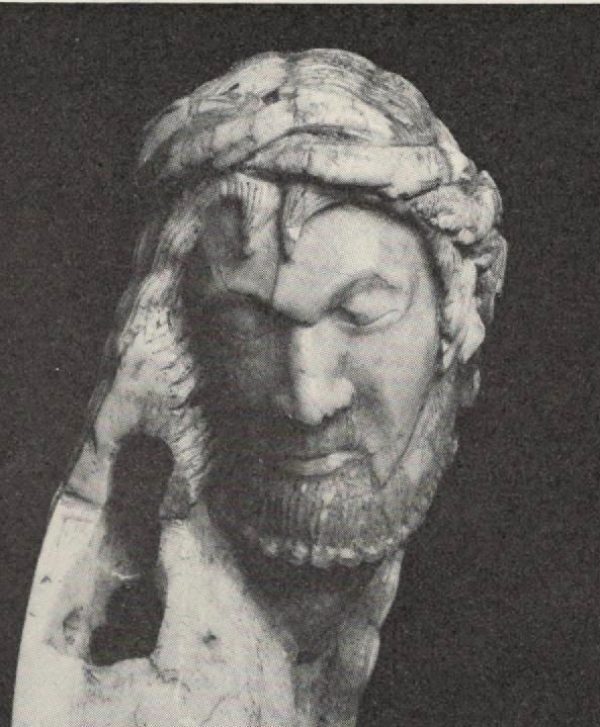

Meanwhile, the search for the missing figure of the crucified Christ from the front of the Cross resulted in the identification of a potential candidate in the Kunstindustrimuseet in Oslo. The Oslo Corpus was duly displayed on the Cloisters Cross in The Year 1200 exhibition in 1970 (Fig. 7.4), and the association was generally accepted.5 Various people claimed credit for this ‘discovery’, including Thomas Hoving, Florens Deuchler, and John Beckwith, but only Martin Blindheim, so far as I know, had already put it in writing (in 1969).6 However not everyone was convinced, most significantly Willibald Sauerländer, who in his review of the exhibition was dismissive of the whole idea. His scepticism was couched thus: ‘On the one hand we have a highly sophisticated composition with tiny figures, covered by inscriptions and charged with a complicated and pretentious program, on the other a piece of the highest quality of carving depending for its appeal on the vigour of its physical appearance and the drama of form, rather than a network of allegorical interrelations’.7 An unfortunate implication is that the Cross is not a piece of carving of the highest quality and its figures lack vigour and drama. But is that true of, for example, the central medallions? And how would it be possible for the Oslo Corpus on its own to comprise ‘allegorical interrelations’? It clearly needs the context of a cross, such as the Cloisters Cross, for such relations to be apparent or even possible. I will argue in due course that when the two objects are seen together, any stylistic differences are entirely the result of scale (and the amount of detail possible) and that a dialogue between the two pieces becomes insistent, complementary, and compelling.

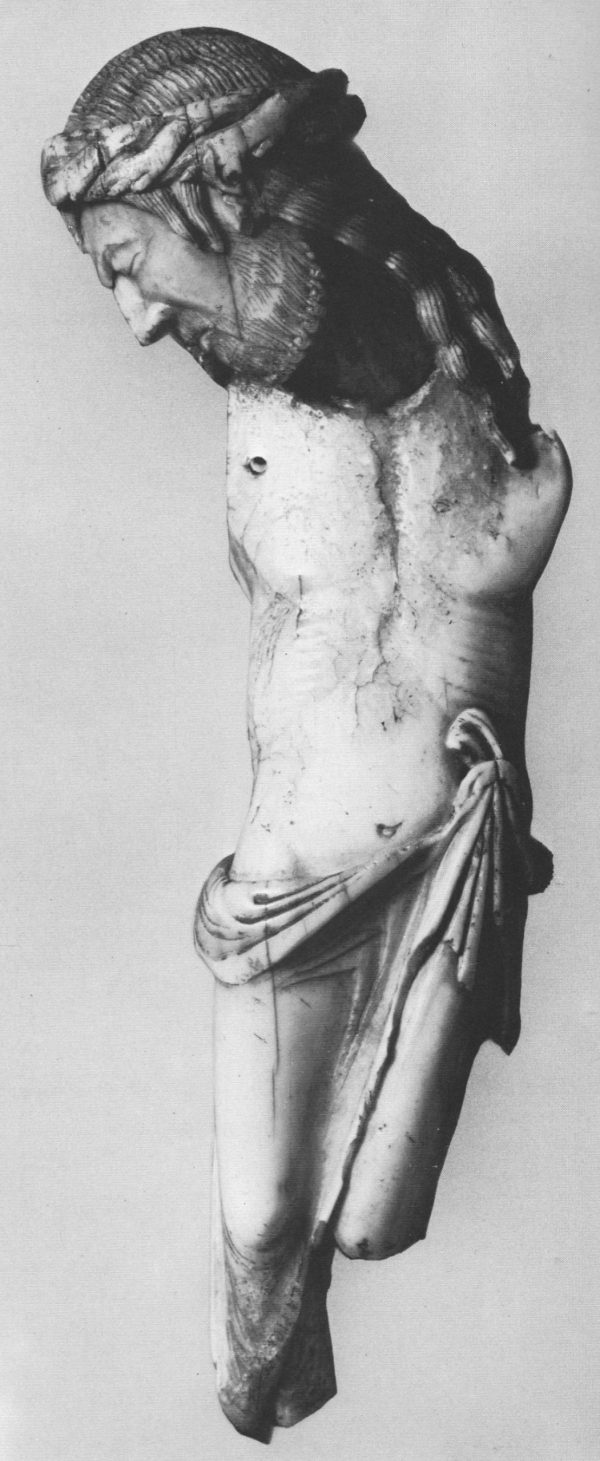

The main problems identified by critics have been that Christ as shown on the Oslo Corpus wears the Crown of Thorns; and the position of his legs have suggested to Sauerländer and some subsequent commentators that his two feet overlapped and were pierced by a single nail.8 Ergo, the Corpus is Gothic whereas the Cross is late Romanesque; they could not possibly belong together. This perception was endorsed as recently as 2022 by Rainer Kahsnitz for whom the carving in Oslo is ‘nach 1200/1210’, while he dates the Cross (and the Pilate plaque) to the third quarter of the twelfth century.9 The use of only three nails and the presence of the Crown would, such critics argue, push the Oslo Corpus into the thirteenth century, when the Crown and three nails, rather than four, were increasingly preferred. However, as Christ’s lower legs are missing from the Corpus, it is not clear to me how any conclusions can be drawn about the nail or nails in his feet—it is far from obvious that his legs were crossed, and if they were side by side his feet could have been too. Also problematic is how late we would have to date the Corpus for a single nail and the Crown of Thorns to be commonplace—arguably the second half of the thirteenth century. But the style of the drapery of the Corpus suggests a late Romanesque origin.10

Perhaps for these reasons, other scholars persisted in linking the Cross and the Corpus: they were shown together at Beckwith’s exhibition of English ivories at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London in 1974 and in English Romanesque Art 1066–1200 at the Hayward Gallery in London in 1984.11 In Hoving’s King of the Confessors, published in 1981, they were still treated as a unit (he seems always to have retained this view), but in the community of historians of medieval art, mention of their association was gradually abandoned, without the case in its favour ever being set out in any detail.12

The Relationships between Corpus and Cross

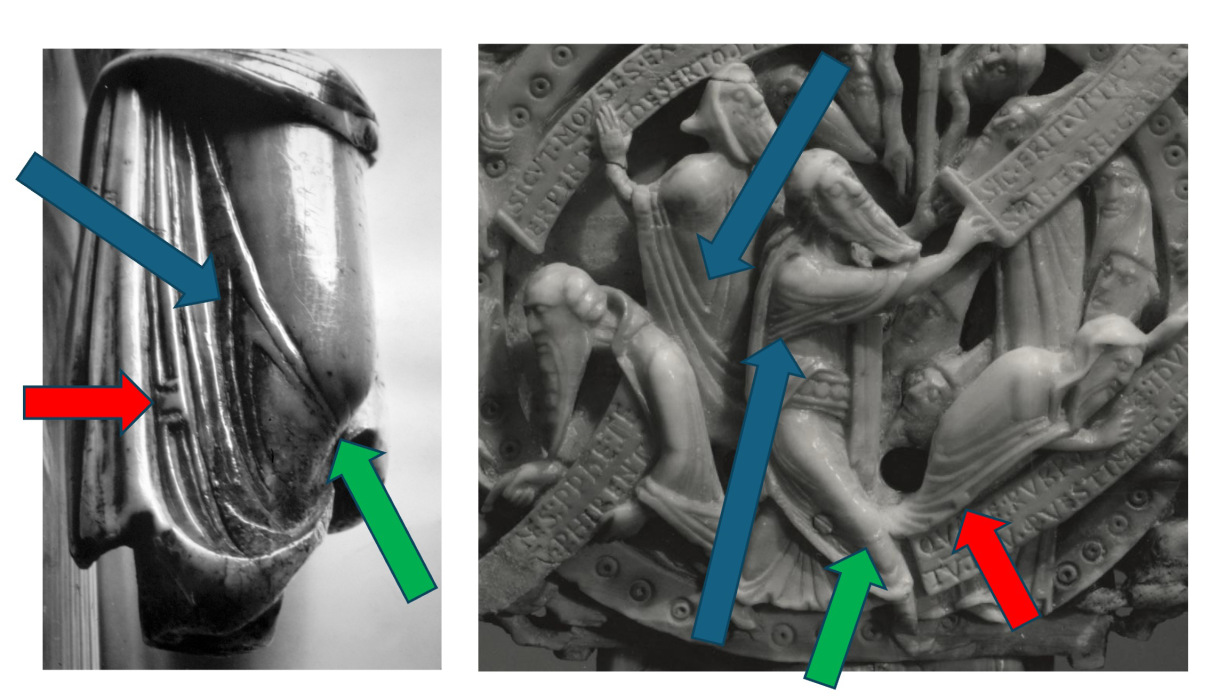

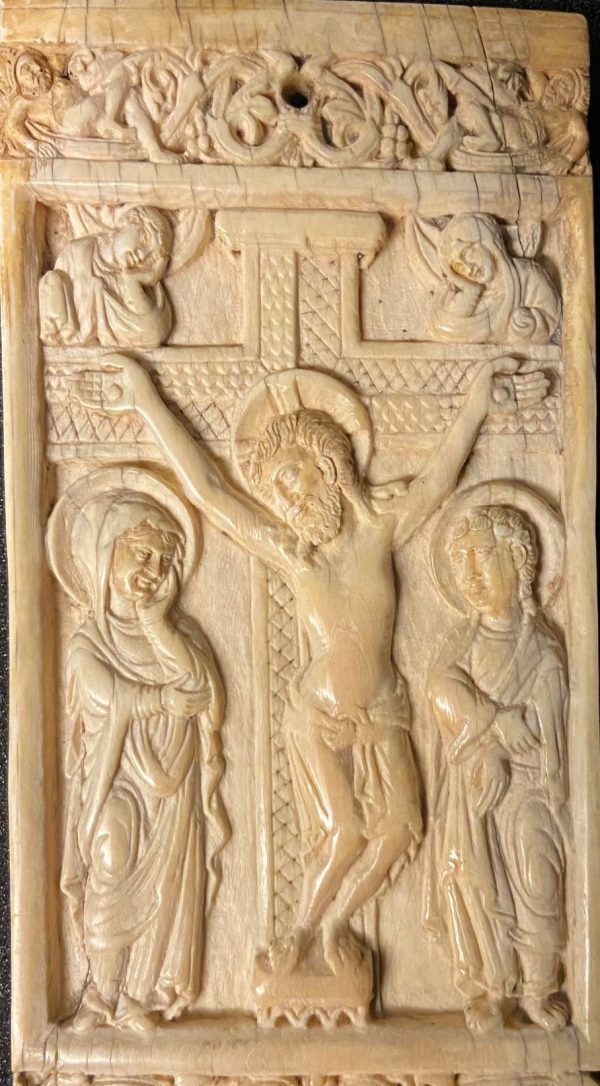

The close connection between Cross and Corpus can be argued on the basis of style, iconography, and cultural ideology, which is what this section of my essay explores. Its final part turns to the consequences that follow if the two pieces were indeed made for each other. My long-standing view is that there are so many points of visual cross reference between the two carvings that they are likely to be contemporary and related. An obvious place to start is a comparison of the figure of Christ in the Good Friday plaque on the Cross with the Oslo Corpus. Firstly, despite the discrepancy in size (35 mm in height for Christ in the Good Friday plaque versus 210 mm in height, when complete, for the Oslo Corpus—six times larger), the proportions are remarkably similar (Figs. 7.5 and 7.6). When the Deposition figure is scaled up, it will be seen that Christ’s shoulders, navel, knees, and feet are about level with those of the Corpus and can be linked with almost parallel horizontal lines. Secondly, both figures show the loincloth disposed to uncover the left thigh of Christ, and both loincloths have a remarkably similar knot at Christ’s left hip. When it comes to anatomy, we may note the similar arrangement of ribs (shallow curves) and the notched sternum, and perhaps the wavy hair falling on the shoulders. The tress of hair on Christ’s right (dexter) shoulder on the Good Friday plaque was once matched by one on the Oslo Corpus, as the extant hairlines on the latter make clear. Just as telling are the common elements in the rendering of drapery. Both the Corpus and the Cross employ a late version of so-called damp fold, in which areas of cloth cling to the body. These adhering patches are articulated in some places by nested V-folds, occasional curving rolls (like thin pipes), and small ‘bridges’ over furrows at the edges of garments (Fig. 7.7). I do not know another single, three-dimensional crucifix figure in any medium with all these characteristics.

Damp fold (clinging cloth): clinging knee roll (green), vested V folds (blue) and bridges over furrows (red).

But this is so formalist—the Oslo Corpus is great sculpture, as Sauerländer recognised. The carving of the face depicts the pain of Christ’s death, which is what can be read on the side of the Cloister Cross in the words Dei penam mor . . . (the pain of the death of God, or the pain of God dying) (Fig. 7.8).13 This juxtaposition is unlikely to be just happenstance, for the inscription on the other edge, adjacent to Christ’s naked thigh, includes the words nuda videt pudibunda (he [Cham] sees the naked shame) (Fig. 7.9). The location of these verses has been selected to highlight the rare visual characteristics of the Oslo Corpus, or something very like it. If, for example, the terra tremit (the earth trembles) couplet had been written there, no expressive connection would be found.

Another eloquent aspect of the original corpus (even if it was not ‘Oslo’) would have been the raised arms of Christ. The large central roundel, with its concentration of imagery and texts at the intersection of the horizontal and vertical arms of the Cloisters Cross, makes it virtually certain that this figurative ‘halo’ was meant to be readily visible, which would have necessitated lowering the position of Christ’s head, tipping it to one side, and angling his arms at about forty-five degrees, as suggested by the 1970s positioning (see Figs. 7.4 and 7.5). It seems that Christ’s right arm rose up against the side of his face, as though it was supporting the weight of his head. Photographs of the Corpus from the back indicate an angle of about 135 degrees for the mortice joint on the shoulder of the carving (Fig. 7.10). Indeed, the angles of the socket holes for the arms of the Oslo Corpus indicate, as Parker and Little realised, ‘that the arms originally sloped sharply upwards’, noting however that ‘such a position is difficult to equate with a Romanesque corpus’.14 But logic suggests that this had to be the arrangement. For either Christ’s body was low on the Cross, with raised arms and bowed head, or his arms were shorter and outstretched horizontally, with the rest of his body (head to foot) being higher up the Cross, obscuring the central medallion. The locations of the nail holes securing Christ’s hands and feet determine their positions. It is quite apparent how unnatural the proportions of his trunk and limbs would be if a standard, cross-shaped Romanesque crucifix figure had been intended.

Although they are not common, antecedents of this pose can be found from the time of the Gero Cross in Cologne cathedral (late tenth century) onwards and invariably contribute to a sense of the torture of crucifixion. Another early example is the engraved Crucifixion on the reverse of the Lothar Cross; there also are three ivory plaques on or from book covers that have this characteristic.15 The ivory plaques have been dated to the mid-eleventh century and their origin located in Echternach (in modern Luxembourg) or the Middle Rhein. One of the plaques, now in the British Museum, may be the latest of the group (Fig. 7.11).16 This format is nothing like Christus triumphans nor Christus patiens, the suffering Christ, but depicts instead the moment of his death. Sabrina Longland’s research long ago showed that patientis (suffering) was the usual word chosen for the many variants of the Cham ridet verse, but on the Cross it is changed to mor[ientis] (dying).17 This is a cross concerned with death (albeit with the hope of eternal life). Its soteriological position is that those who will be saved are those who believe that this was the purpose of Christ’s death. For me, the detailed carving of the figured halo and the raised arms and facial expression of the Oslo Corpus speak of a carefully coordinated vision composed for this crucifix to the extent that it makes the combination of unusual but not unparalleled features all the more purposeful. As an example, the scroll held by Isaiah as he looks down from the central halo asks ‘why are you red in your apparel?’ (Isaiah 63:2), which continues ‘like one who treads grapes in the winepress’. The loincloth of the Oslo Corpus has surviving traces of red pigment—not a widespread colour for it in any medium. The point here is that in his sacrifice Christ has prepared the wine, which is his blood, for the redemption of humankind. Surely if the Cloisters Cross is a ‘great work of art’ (and if it isn’t why the fuss?) we would expect a careful coordination between its parts, in which case there is no more reason for the figure of the crucified Christ to be conformist than the Cross itself is. We should be impressed, rather than surprised, at the ways the artist has contrived an emotionally consistent, distinctive and expressive masterpiece.

There are hundreds of depictions of the crucified Christ in Romanesque art in many different media. The most comprehensive collection is Peter Bloch’s catalogue of copper-alloy corpora. They number over six hundred, but very few can be identified as having any relevant characteristics. Focusing on one detail, the knot in the loincloth at Christ’s left hip and his uncovered thigh, there are about a dozen depictions (2 percent of the total) which are broadly similar, the earliest of which is on Bernward of Hildesheim’s silver cross.18 The origin of the format can be found on various Carolingian ivory plaques, usually book covers attributed to Metz between 850 and 900 (Fig. 7.12); it also occurs on engraved crystals of similar date.19 This Carolingian ancestry indicates the formal origins of the figure of Christ on the Good Friday plaque and the Oslo Corpus. But although widely disseminated in northern Europe, Christ’s naked thigh was not often depicted in the Romanesque period, presumably because it was shameful. Two other characteristics of the Deposition point to similar sources: the Virgin’s bowed head and veiled hands and St John’s expression of grief, resting his tilted head on his right hand. Both are attested on ivories and in manuscripts from the mid-ninth century, for example in the Crucifixion initial of the Drogo Sacramentary.20

To summarise the essentials, the Good Friday plaque strongly suggests that the main figure of Christ crucified be shown with his loincloth knotted at his left hip and his left thigh exposed. The elaborate central boss on the front of the Cross effectively requires the arms of the corpus (whether the Oslo Corpus or any other) to be raised at a steep angle so that Christ’s head does not obscure the detailed carving. As it happens, the position of the nail holes on the Cross allows a reconstruction of the Oslo Corpus which matches the proportions of Christ on the Good Friday plaque. Juxtaposition of ‘the pain of dying’ with the expression on Christ’s face and of ‘naked shame’ with his uncovered limb is more than coincidentally appropriate. And stylistically the draperies on the Cross and the Corpus share the same characteristic quirks of late Romanesque damp fold, with a similar commitment to articulating the bodies beneath the cloth.

Gunhild’s cross, the Cloisters cross and Letter forms.

The presence of the Crown of Thorns on the Oslo Corpus merits particular attention, as it has been argued that representations of the Crown do not predate the acquisition of the relic by King Louis IX of France in 1239. However, there are exceptions to this ‘rule’, two of them ivory carvings. The earlier is Anglo-Saxon, perhaps circa 1050, and attached to a gold and enamel cross now in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London (Fig. 7.19).32 Christ’s head bears a circlet in the form of a two-ply twist, his eyes are closed, and his expression pained—similar, in those respects, to the Oslo Corpus. It may be noted that the Abbeys of Abingdon and Malmesbury both claimed relics of the Crown of Thorns as gifts from King Athelstan (r. 924–937).33 A second, later example (ca. 1200) is also English and now in the Hunt Museum in Limerick.34 The Crown of Thorns was also seen in two late twelfth-century visions, at Dunstable in 1188 and the Abbey of Eynsham in 1196.35 The former occurred in the context of preparations and recruitment for the Third Crusade, implicitly criticising the warfare between France and England as a distraction from the fight that is worth fighting. All versions of the vision at Dunstable stress the blood flowing from the body of Christ crucified. Its purpose as a ‘recruiting agent’ for the Third Crusade in August 1188 (on the vigil of Saint Laurence) is hard to ignore.36 There is no denying the words ‘and crowned with thorns’ (et spinae coronatus) in one recension of Roger of Howden’s text, but several commentators have sought alternative readings of the headbands on the V&A and Hunt carvings, such as ‘wreath’ or ‘rope crown’. This seems to me like special pleading.37 In the absence of examples of rope crowns, why would a viewer of the V&A crucifixion reliquary think to interpret it in such a way?

The presence and explicitly thorny character of the Crown on the Oslo Corpus also suggests a specific focus on the trials and tribulations of kingship (Fig. 7.20). Cnut VI had good reason to be conscious of the hazards of his inheritance. As noted above, his predecessor-namesake Cnut IV (Cnut the Saint) had been martyred by his own men at Odense in 1086 and formally canonised by the pope around 1100. Cnut VI’s grandfather Cnut Lavard, duke of Schleswig and subsequently also of Holstein (and recognised in Jutland as King Cnut V), was assassinated by his cousin Magnus in 1131 and canonised in 1170.38 His burial place was the Benedictine monastery at Ringsted where his son King Waldemar and grandson, Cnut VI himself, ultimately joined him. It was the family mausoleum and, perhaps, the church for which the Cloisters Cross was made.

Kings David and Solomon are represented on the Cloisters Cross with prophetic scrolls and placed above the titulus board and Hand of God as if stressing that this upper section of the vertical shaft of the Cross leading up to the Ascension was especially dedicated to ordained monarchy. Rather unexpectedly, David and Solomon do not wear lily crowns or diadems but helmets (Fig. 7.21). This form of headgear (sometimes called Spangenhelm [barred helmet] or Kreuzbügelkrone [cross-framed crown]) had been an option for rulers from antiquity onwards, but by the twelfth century was decreasing in use. An exception is Cnut VI, who chose it for the majesty side of his great seal (Fig. 7.22). Its military connotations express an important aspect of Cnut’s foreign policy: the suppression and conversion of the pagan Wends, who lived to the east of Denmark along the southern shores of the Baltic Sea.39 There were military expeditions against them throughout Cnut’s reign, often supervised by Absalon, archbishop of Lund, ‘close to being the greatest ever campaigner and warrior here in the north’.40 This policy had been paramount for a century or more and was political and territorial as much as religious. Such ‘struggles’ were ongoing, but after the fall of Jerusalem to Saladin in 1187, the ultimate triumph of Christianity faced other more important foes: Jews and Muslims. One way of seeking to comprehend the decision to designate Christ as ‘king of the confessors’ is that redemption will come only to those who acknowledge his lordship. But as so many did not, those Christians in power, such as the Western European kings, were forced into the fundamentalist position of striving to make the whole world (as it was then understood) believe in salvation through commitment to Christ.

One of the manifold uncertainties about the Cloisters Cross is its date, which impinges on how it is interpreted. For example, if its making follows the fall of Jerusalem in October 1187 and the initiation of the Third Crusade, it coincides with a widespread persecution of the Jews in Europe, which then becomes a factor in assessing the vitriol of its main inscriptions. It must be stressed that there was no Jewish community in Scandinavia at the time. Their presence in visual and verbal polemic is adoptive, being used to convey alterity and highlight what good Christians are not.41 Other aspects of the Cross can be brought into play here, notably the pairing of Synagoga and the agnus dei on the central roundel of the reverse and the scroll held by the adjacent figure, the prophet Balaam (Fig. 7.23). Synagoga is normally contrasted with Ecclesia, as on Gunhild’s Cross, but for some reason that was not the best option in this context where the Lamb of God—the sacrificial Christ, not the living Church—is deemed more appropriate. However, the foes do not confront each other; Synagoga turns her back on the Lamb and he turns his head away from her while leaving his breast exposed to her lance, very much as happens in the Gospel Book of Henry the Lion and Matilda of England.42

Balaam’s scroll merits attention too, for it gives his prophecy in Numbers 24:17 as ‘consurget homo de Israel’ (a man shall arise from Israel), substituting for the Vulgate’s virga, so a man shall arise rather than a rod or sceptre.43 This may in part have been because virga was often interpreted as relating to the Virgin Mary (virgo) rather than Christ (who was the flower on the rod). Whatever the case, the text clearly triggered or was prompted by a reminiscence of Isaiah’s prophecy (11:1) that the Messiah would come from the rod and root of Jesse. That might justify the next quote on Balaam’s scroll, from Isaiah 11:10: ‘et erit sepulchrum eius gloriosum’ (and his sepulchre shall be glorious). This is the only scroll on the Cross to conflate texts from separate books of the Bible (Numbers and Isaiah). Also, non-Vulgate quotations are generally hard to find on the Cross (for virga rex confessorum. The designer was clearly well versed in Holy Writ, and the carver was careful in transcribing and abbreviating the texts he was given, so these are more likely to be premeditated changes than accidental errors.

One explanation for the tactic is that by rewriting virga as homo in relation to sepulcrum, the designer of the Cross alluded specifically to Christ’s resurrection and its location in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. The Sepulchre was often specified as the ultimate goal of a crusade: the entry on Urban II in Liber pontificalis credits Gregory VII with the idea of ‘an expedition to Jerusalem for the defence of the Christian faith and the liberation of the Lord’s Sepulchre from the hands of enemies’, and this focus was maintained for the next century.44 In 1190, Pope Clement III called the Third Crusade ‘the journey to the Holy Sepulchre’.45 The enemies of the faithful are specified in Isaiah 11:13–14, where Isaiah prophesied that the coming together of the faithful would defeat or subdue the ungodly, identified as Philistines, Edomites, Moabites, and Ammonites. It is a rallying cry to unite the righteous by implication, so that the god-man’s tomb may once again be glorious and purged of unbelievers. There is a purposeful decision evident in bolting Isaiah 11:10, and implicitly what follows in the rest of the chapter, onto Numbers 24:17, for it reinforces the suggestion that the anti-Jewish rhetoric on the Cross should be understood more broadly as an attack on all non-Christians at a time of aggravated hostility.

As regards the Third Crusade itself, the Danes were early on the scene, their ships helping to blockade the port of Acre in September 1189 after it had fallen to Saladin. A letter from Pope Clement III to Emperor Isaac II Angelos praises the Danes for their prompt response. Their squadron, perhaps assembled under the auspices of a recently formed naval military order, the piratica of Roskilde, presumably had royal support.46 According to a contemporary witness, the Danish expedition comprised fifty ships and twelve thousand men of whom ‘hardly 100’ survived the recapture of Acre.47 Another contingent of fighters set off from Denmark two years later: four hundred men and a mysterious nepos regis (king’s nephew), though which relative of Cnut’s has never been firmly established.48 They arrived in 1192, after Richard I and Saladin had concluded their three-year truce, and so they returned from the Levant to Denmark in 1193.49 This prompted the composition of a panegyric, the Historia de profectione Danorum in Hierosolymam, with a dedicatory letter addressed to a dominus K, most probably the king himself.50

Contemporaneous visual evidence for crusading interests in Denmark may be identified on the elaborate sculpted gable over the south door of Ribe Cathedral (Figs. 7.24 and 7.25). The gable imagery has been interpreted before as a call to arms to fight the infidel, but against the pagan Slavs rather than in the Holy Land.51 However, Ribe’s location is hardly suitable as a rallying point for a campaign in the Baltic, whereas it is well-placed as the rendezvous for a seaborne journey to the Mediterranean, especially as it was joined by a Frisian contingent. Positioned above an earlier carved tympanum depicting the Deposition, the gable’s central focus is reminiscent of a Coronation of the Virgin, with Mary (labelled S’ MARIA) crowned and enthroned alongside Christ, also crowned. Above them is inscribed CIVITAS IERUSALEM, and between them is a cross, its lower shaft held jointly in their hands. Beneath their feet are a queen, a king, and a bishop. To either side are angels holding scrolls, on the dexter side with the opening words of the Sermon on the Mount, ‘Beati pauperes spiritu’ (How blessed are the poor in spirit [Matthew 5:3; cf. Luke 6:20]), and opposite ‘Venite ascendamus ad montem dei’. The latter derives from Isaiah 2:2–3: ‘Et erit in novissimus diebus praeperatus mons domus domini in vertice montium et elevator super colles; et fluent ad eum omnes gentes, et ibunt populi multi, et dicent “venite et ascendamus ad montem domini, et ad domum dei iacob, et docebit nos vias suas”’ (and it will happen in the latter days that the mountain of God’s house will rise higher than the heights and tower over the hills, then all the nations will flock to it. Many peoples will come to it and say ‘Come, let us go up to the mountain of God, to the house of the God of Jacob that he may teach us his ways’). This gathering of the peoples to learn the ways of the Lord is clearly an earthly event, ‘quia de Sion exibit lex et verbum Domini de Jerusalem’ (for the Law will issue from Zion and the word of God from Jerusalem), and is surely encouraging a ‘pilgrimage’ to the mount where Christ set out his manifesto. These texts effectively rule out the possibility that heavenly Jerusalem was specifically intended. Is there a need for preaching in Heaven, would access to it be open to any who did not already know the ways of the Lord? The Historia de profectione Danorum, mentioned above, adopts the trope (in chapter 6) that the expedition of 1191 was going to ‘the Promised Land, flowing with milk and honey’ (ut videre mererentur terram promissionis fluentem lac et mel). The author proceeds to conflate this land with the Virgin Mary.52

There is no reason for this crusading rhetoric not to be applicable at Ribe at any date after 1188. The fact that the earthly king, below Christ and Mary, holds a cross which he raises up to Mary, to whom the cathedral is dedicated, and that she touches it with the extended fingers of her right hand as though consecrating it, implies that sanction is being sought from Mary for the expedition made by the crowds gathered below as they embark for Jerusalem. The inclusion of the suppliant king and queen below is possibly just a patriotic gesture, showing the loyalty of the bishop of Ribe or perhaps Archbishop Absalon, who combined the roles of spiritual and military director of Cnut’s kingdom. I am not suggesting here that the gable sculpture is prospective but rather that it was a commemorative tribute carved after the event to enhance the record of Cnut and Gertrude’s commitment to crusading in general and the liberation of Jerusalem in particular. That makes its date uncertain, except for a terminus post quem of 1188, though it may be pertinent that the bishop of Ribe from 1204 was Olaf, previously Cnut VI’s chancellor and recorded as having given an ivory cross to his cathedral.53

In addition to cultural and ideological factors, it seems to me that the composition of the Ribe gable has some formal similarities with the Cloisters Cross, perhaps most noticeably in the tilted heads and long jutting beards of the lower figures and, of course, the scrolls with biblical inscriptions. The sense of dense activity and the variety in the letter forms also make interesting comparisons. While not suggesting that the gable is as sophisticated in conception or skilled in execution as the Cloisters Cross, to my eye both are plausibly carvings from the same artistic milieu. This is not to argue that the Cross and the gable are directly dependent on each other but rather that they evince comparable approaches to biblical text and its use in militant Christian rhetoric.

The Cloisters Cross is a dour object and the Oslo Corpus complements it physically and ideologically. Together they constitute a sophisticated, complex, but carefully planned work of art which must have been conceived in its extraordinary detail by a churchman of considerable learning and an inventive turn of mind. An obvious candidate would be Absalon, bishop of Roskilde and archbishop of Lund, who studied in Paris in the 1140s. Another possibility is his friend and contemporary William of Aebelholt, the sub-prior of Saint-Victor in Paris, who in 1165 was chosen by Absalon to be abbot of Eskilso, just north of Roskilde in Zealand. William retained close contacts with Paris, most notably in the negotiations with King Philip Augustus over the repudiation of his queen, Cnut VI’s sister Ingeborg. But several other leading clerics in Denmark had links with Paris, including Omer, bishop of Ribe, who corresponded with Stephen of Tournai, the abbot of Sainte-Geneviève in Paris. Stephen had been a canon at Saint-Victor and later became bishop of Tournai (1192–1203). Stephen was also closely connected with Queen Ingeborg and perhaps involved in the production of her grand illuminated psalter.54

There has been an unfortunate tendency to regard Denmark, and Scandinavia in general, as peripheral to the great centres of high medieval artistic and intellectual endeavour. But during the reigns of Cnut VI and his brother Waldemar II, ‘the Danish king was one of the greatest powers in Europe’.55 Furthermore, the late twelfth century was almost unparalleled in its internationalism; much evidence shows the strength of Denmark’s connections with the British Isles, northern Germany, the Low Countries, northern France, and the Mediterranean.56 It is those contacts with learned churchmen and accomplished artists that underpin the remarkable creation of the Cloisters Cross and its figure of the crucified Christ now in Oslo.

To be clear, this is not an overarching claim that the Cross and its corpus need be of purely Danish manufacture (whatever that might mean): the carver could have been English or German by origin or training; the ‘learned advisor’ who selected the content very probably studied in Paris. Attempts to determine such things depend perhaps on pursuing small, unusual, and apparently minor details. But small details, such as the beading on the lopped cross—suggesting perhaps that it is both jewelled and a rough instrument of torture—are meaningful (alluding to both pain and triumph) and are likely to matter as much to the patron as to the artist or the designer of the iconography.57

The way forward proposed in this paper for approaching such conundrums is that establishing the impulse for creation is critical. Who would have wanted such an object as the Cloisters Cross and in what circumstances? It is easy to underestimate the physical, ideological, intellectual, and artistic effort (the capital) that would go into an ivory carving. The decision to turn Christ’s halo into a complex of figures and inscriptions had ramifications: making its content visible required rethinking the ‘normal’ position of Christ on the Cross. Various other entailments, perhaps including composing the terra tremit verse, required an awareness of options and a flexibility in organising them into a coherent whole. Where did this energy and determination come from? This is a rhetorical question, but also a challenge for anyone seeking to locate the Cross. My tentative resolution of these questions has been guided by three principal considerations. First is the conviction that the Oslo Corpus was made for the Cloisters Cross and, as a corollary, that a Danish provenance has to be taken seriously. Then there is the relationship with Gunhild’s Cross, which serves as a precursor to the Cloisters Cross in several respects. Finally, there are the people, the cultural environment, and (perhaps most importantly) the political moment that could have occasioned this artistic statement of fundamental Christian beliefs: effectively a credo carved in ivory.

Citations

[1] I would like to thank Margit Thøfner, Lloyd de Beer, and Nick Trend for their help with aspects of this essay, and Jack Heslop for drawing the map.

[2] Elizabeth C. Parker and Charles T. Little, The Cloisters Cross: Its Art and Meaning (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1994); and Bernice R. Jones, ‘A Reconsideration of the Cloisters Cross with the Caiaphas Plaque Restored to Its Base’, Gesta 30, no. 1 (1991): 65–88.

[3] On Jewish hats, see, for example, Sara Lipton, Images of Intolerance: The Representation of Jews and Judaism in the Bible Moralisée (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), 15–19. The Roman headgear is similar to many war bonnets shown in imagery representing kings and nobles in military guise in the second half of the twelfth century. For example, see the Geoffrey of Anjou enamel plaque in Le Mans (Peter Lasko, Ars Sacra, 800–1200, 2nd ed. [New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1994], 247–48, plate 338); or the great seals of King Stephen (George Zarnecki, Janet Holt, and Tristram Holland, eds., English Romanesque Art 1066–1200: Catalogue of an Exhibition Held at Hayward Gallery London, 5 April–8 July 1984 [London: Arts Council, with Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1984], cat. nos. 331 and 332, both illustrated at 303).

[4] Parker and Little, Cloisters Cross, 262–63n26.

[5] Konrad Hoffmann, The Year 1200: A Centennial Exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1970), cat. nos. 60 and 61, colour photo of the Cross and the Oslo Corpus together on xviii.

[6] Martin Blindheim, ‘En romansk Kristus-figur av Hvalrosstann’, in Kunstindustrimuseet i Oslo, Årbok, 1969 (Oslo: Kunstindustrimuseet, 1968–69), 22–32.

[7] Willibald Sauerländer, ‘“The Year 1200”, a Centennial Exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, February 12–May 10, 1970’, The Art Bulletin 53, no. 4 (1971): 512.

[8] Sauerländer, ‘“The Year 1200”’, 512–13. See also, for example, Tage Christiansen, ‘Ivories: Authenticities and Relationships’, Acta Archaeologica 46 (1975): 123–33.

[9] Rainer Kahsnitz, Goldschmidt Addenda: Nachträge zu den Bänden I–IV des Elfenbeincorpus von Adolph Goldschmidt, Berlin 1914–1926, Sonderucke aus der Zeitschrift des Deutschen Verein für Kunstwissenschaft 68, 72/73 (Berlin: Deutscher Verlag für Kunstgwissenschaft, 2022), cat. nos. 157, 155, 156, respectively.

[10] It would be interesting to know the date (precise or approximate) of the earliest extant instance anyone can find of Christ crucified with three nails and wearing the Crown of Thorns.

[11] John Beckwith, ed., Ivory Carvings in Early Medieval England, 700–1200 (London: Victoria and Albert Museum, Arts Council, 1974), cat. no. 61 for the Cross and cat. no. 62 for the Corpus; Beckwith, 96: ‘This figure [the Oslo Corpus] may well belong to No. 61’. See also Zarnecki, Holt, and Holland, English Romanesque Art 1066–1200, cat. nos. 206, 207 and 208.

[12] Thomas Hoving, King of the Confessors (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1981), 329.

[13] For reasons of poetic consistency, the final word is usually extended as morientis, but there does not seem to be enough room for so many letters. This was pointed out in a lecture (unpublished) by Hoving. The alternative, mortis, will fit the space but does not have the same metre of short and long syllables.

[14] Parker and Little, Cloisters Cross, 255.

[15] For the Lothar Cross, see Lasko, Ars Sacra, 101 and plate 139 (where it is dated ca. 985/91), or more legibly in Hanns Swarzenski, Monuments of Romanesque Art (London: Faber and Faber, 1954), plate 29, fig. 71.

[16] For the ivory plaques, see Adolph Goldschmidt, Die Elfenbeinskulpturen aus der Zeit der karolingischen und sächischen Kaiser, VIII.–XI. Jahrhundert, vol. 2 (Berlin: B. Cassirer, 1914), cat. nos. 29–31. The first two are still found on the covers of manuscripts. Goldschmidt compares the workmanship of no. 31 (in the British Museum) with an ivory Virgin and Child relief now in Antwerp (his no. 33). They have very similar foliate scroll borders and a liking for patterned surfaces which look to my eye to be more mature Romanesque (twelfth century) than ca. 1050.

[17]Longland notes the harshness of nuda pudibunda (naked shame) as against detecta membra (uncovered limbs) and morientis (dying) as against patientis (suffering). The English translations are inevitably approximate; the Latin words had more subtle connotations in the twelfth century. Sabrina Longland, ‘A Literary Aspect of the Bury St. Edmunds Cross’, Metropolitan Museum Journal 2 (1969): 54, 56, 74.

[18] Peter Bloch, Romanische Bronzekruzifixe, Bronzegeräte des Mittelalters 5 (Berlin: Deutscher Verlag für Kunstwissenschaft, 1992), VI A 1, with related examples following. It may be noted that the late twelfth-century derivative, VI A 2, has arms more steeply raised.

[19] For example, Lasko, Ars Sacra, plates 36, 69, 77. For a discussion of V&A Inv. no. 251-1867, illustrated in Fig. 7.12 , see Paul Williamson, Medieval Ivory Carvings: Early Christian to Romanesque (London: V&A Publishing, 2010), cat. no. 44.

[20] Celia Chazelle, The Crucified God in the Carolingian Era: Theology and Art of Christ’s Passion (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 255–66, fig. 27.

[21] Emil Hannover, ‘Et middelalderlight norsk Hvalros-Krucifix i dansk Privateje’, in Kunst og Haandverk, Nordiske studier (til) Johan Bøgh 1848–1918, ed. A. W. Brøgger, Emil Hannover, and Axel L. Romdahl (Kristiania: Cammermeyers forl, 1918), 96–102.

[22] T. A. Heslop, ‘Gunhild’s Cross, Seeing a Romanesque Masterwork through Denmark’, Art History 43, no. 2 (2020): 433–57.

[23] Of the two forms that do not appear on Gunhild’s Cross but are on the Cloisters Cross, the more common is a capital L with a curving upright and horizontal bar; it occurs widely in Saxony. The rarest form on the Cloisters Cross is the curious ampersand seen on the scrolls held by David, Solomon, and Job, among others. The closest parallel I have found is in the prayer Suscipere digneris added to the Copenhagen Psalter soon after 1200. See Christopher Norton, ‘Archbishop Eystein, King Magnus and the Copenhagen Psalter – A New Hypothesis’, in Eystein Erlendsson: Erkebiskop, Politiker og Kirkebygger, ed. Kristin Bjørlykke, Øystein Ekroll, Birgitta Syrstad Gran, and Marianne Herman (Trondheim: Nidaros Domkirkes, 2012), fig. 6.

[24] Copenhagen Psalter, MS Thott 143.2, Royal Library, Copenhagen. Patricia Stirnemann, ‘The Copenhagen Psalter Reconsidered as a Coronation Present for Canute VI’, in The Illuminated Psalter: Studies in the Content, Purpose and Placement of Its Images, ed. F. O. Büttner (Turnhout: Brepols, 2004), 323–38.

[25] The Entry into Jerusalem miniature and the relic list are discussed by Norton, ‘Archbishop Eystein, King Magnus and the Copenhagen Psalter’, 185–215. The name in the erased inscription (Norton’s fig. 8) seems to have had three ascenders at the beginning and another very soon after, so it could be Waldemar (Cnut’s brother and successor) but is hard to construe as Magnus, Norton’s preferred candidate.

[26] John Munns, ‘Relocating the Cloisters Cross’, The Burlington Magazine 155, no. 1323 (2013): 381–83; and see Cecily Hennessy’s essay in this volume.

[27] The passage continues ‘like one who tramples grapes’—the reference as a whole thus implicitly comparing the wine of the Eucharist with Christ’s blood.

[28] Stammheim Missal, MS 64, J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. See Elizabeth C. Teviotdale, The Stammheim Missal (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2004), 63–65.

[29] One instance is the Adalbero ivory book cover of ca. 1000 in Metz. See Parker and Little, Cloisters Cross, ill. 125.

[30] Parker and Little, Cloisters Cross, 65, 86.

[31] Bible moralisée, cod. 1179, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna, is one of the grandest manuscript projects of early Gothic illumination. See Katherine Tachau, ‘The King in the Manuscript: The Presentation Inscription of the Vienna Latina Bible Moralisée’, Gesta 60, no. 1 (2021): 1–30. There are many resonances between the Cloisters Cross and the Vienna Latin Bible moralisée, not least the hostility directed at unbelievers characterised as Jews. See Lipton, Images of Intolerance for this analysis of the contents. It might be worth exploring whether the contemporaneous Vienna French Bible moralisée (cod. 2554, ÖNB, Vienna) was made for Ingeborg at the time of her reconciliation with King Philip in 2013.

[32] Inv. no. 7943–1862, V&A. It is reproduced on a large scale in colour in John Beckwith, Ivory Carvings in Early Medieval England (London: Harvey Miller and Medcalf, 1972), frontispiece, and cat. no. 20.

[33] Otto Lehmann-Brockhaus, Lateinische Schriftquellen zur Kunst in England, Wales und Schottland vom Jahre 901 bis zum Jahre 1307, vol. 3 (Munich: Prestel Verlag, 1956), 219–20, nos. 5944, 5946.

[34] Beckwith, Ivory Carvings (1972), cat. no. 109. The imagery has been misunderstood. A chalice is held up (presumably by Ecclesia—the figure is missing) to catch the blood from Christ’s side wound; the figure opposite holds a vase but turns away. This is Synagoga with a vase of manna from heaven as kept in the Ark of the Covenant (Hebrews 9:4), that is to say, the heavenly food superseded by the Eucharistic wine. It seems likely that this pierced walrus-ivory relief was originally mounted on a portable altar. Synagoga with the pot of manna is found elsewhere in England, for example in the picture cycle prefacing a mid-thirteenth-century Apocalypse in The Eton Roundels, MS 177, fol. 75, Eton College. See Avril Henry, ed., The Eton Roundels: Eton College, MS 177 (‘Figurae bibliorum’): A Colour Facsimile with Transcription, Translation and Commentary (Aldershot: Scolar Press, 1990), 133–34. The origin of this composition is the painted vault of Worcester Chapter House, ca. 1100–10. See T. A. Heslop, ‘The English Origins of the Coronation of the Virgin’, The Burlington Magazine 147, no. 1233 (2005): 790–97.

[35] John Munns, Cross and Culture in Anglo-Norman England: Theology, Imagery, Devotion (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2016), esp. 59 for Eynsham and 260 for Dunstable. In both cases, stress is laid on the tortured and bloody body of Christ.

[36] Interestingly, William of Newburgh post-dates the vision to late 1189. In his chronology he notes an upsurge in English anti-Semitism and the pogroms of 1190. The Jewish persecutors of Christ were one with the Muslim conquerors of Jerusalem who had seized the Holy Cross. This was a war against all unbelievers.

[37] Parker and Little, Cloisters Cross, 258; and compare Munns, Cross and Culture, 260n54.

[38] His canonization coincided with Cnut VI’s first coronation. See Gabor Klaniczay, Holy Rulers and Blessed Princesses: Dynastic Cults in Medieval Central Europe, trans. Eva Pálmai (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007).

[39] Kersti Markus, Visual Culture and Politics in the Baltic Sea region, 1100–1250, trans. Aet Varik (Leiden: Brill, 2020).

[40] Hermann Pálsson and Paul Edwards, eds. and trans., Knytlinga Saga: The History of the Kings of Denmark (Odense: Odense University Press for the City of Odense, 1986), 179; for ‘one of the greatest warriors ever to be born in Denmark’, see Pálsson and Edwards, 161.

[41] Jonathan Adams, ‘“Untilled Field” or “Barren Terrain”? Researching the Portrayal of Jews in Medieval Denmark and Sweden’, in Antisemitism in the North: History and State of Research, ed. Jonathan Adams and Cordelia Heß (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2020), 21–40. See also Lipton, Images of Intolerance, especially for the representation of Judaism in the context of the Albigensian crusade against the Cathars of southwestern France.

[42] See Cecily Hennessy’s essay in this volume.

[43] The Septuagint text of Numbers 24:17 shows anthropos, which means ‘man’. Anthropos is the word written on the dexter side of the Ascension plaque. See Parker and Little, Cloisters Cross, ill. 67.

[44] I. S. Robinson, The Papacy, 1073–1198: Continuity and Innovation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990), 325.

[45] Cited by Robinson, The Papacy, 1073–1198, 325. See also these words from the Chronicle of Monte Cassino: ‘to wrest the Lord’s Sepulchre from the Saracens’, quoted in Robinson, 328. Clement III (1187–91) allowed that a vow to take the cross could be replaced by ‘a subsidy to enable others to make the journey to the Holy Sepulchre’, quoted in Robinson, 336.

[46] For this suggestion, references, and a narrative of the expedition, see Paul Riant, Expéditions et pèlerinages des Scandinaves en Terre Sainte au temps des croisades: Thèse presentée à la Faculté des Lettres de Paris (Paris: Imprimerie Ad. Lainé et J. Havard, 1865), 275–95.

[47] Helen J. Nicholson, trans., The Chronicle of the Third Crusade: A Translation of the Itinerarium peregrinorum et gesta regis Ricardi (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2001), 74. Nicholson suggests (p. 10) that this section of the account was ‘written by a crusader . . . [who] arrived in the Holy Land with the fleet from the north in early September 1189’.

[48] For nepos regis, see Nicholson, Chronicle, 82; and Robert Lee Wolff and Harry W. Hazard, eds., A History of the Crusades, vol. 2, The Later Crusades, 1189–1311 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1962), 50–51, 65.

[49] Karen Skovgaard-Petersen, A Journey to the Promised Land: Crusading Theology in the Historia de profectione Danorum in Hierosolymam (c. 1200) (Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press, 2001).

[50] Skovgaard-Petersen, Journey to the Promised Land, 8, takes this person to be a ‘superior cleric’. The unique (now lost) manuscript of the Historia de profectione Danorum also contained the De bello Judaico of Josephus (about the capture of Jerusalem in AD 70) and a ‘life’ of St Geneviève of Paris. The manuscript was in the council library of Lübeck along with King Waldemar II’s Bible moralisée and was probably part of the Danish royal collection until its seizure in 1226. The proposition is set out in Tachau, ‘The King in the Manuscript’, 24.

[51] For discussions of the imagery, see Per Kristian Madsen, ‘Trekantrelieffet over Ribe Domkirkes Kathoveddør – et monument over en angrende, retmæssig konge’ [The Gable Relief above the gate to the southern transept of the Cathedral of Ribe – a monument to a repentant, rightful king], By, marsk og geest 12 (2000): 5–28; Niels Haastrup, ‘Om Ribes Kathoveddør. To notater: Kattespor og Kongesønnen som metafor’, Romanske Stenarbejder 5 (2003): 281–96; Markus, Visual Culture and Politics, 104–8; and for echoes of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem in the architecture of Ribe, see Markus, 37–39.

[52] ‘Terra ista Virgo Maria fuit, generans Jesum Christum, Deum et hominem’ (This land was the Virgin Mary bringing forth Jesus Christ, both God and man). Quoted in Skovgaard-Petersen, Journey to the Promised Land, 53. The implication is that milk comes from the body and figures Christ’s humanity, whereas honey comes from the dew of heaven and signifies his divinity.

[53] Christiansen, ‘Ivories’, 127, citing Ellen Jørgensen, ‘Ribe Bispekrønike’, in Kirkehistoriske Samlinger, ser. 6, vol. 1, ed. J. Oskar Andersen (Copenhagen: Society for Danish Church History, 1933), 31, where the ivory cross is called a crucifixum de dente ceti (a crucifix of a whale’s tooth).

[54] Ingeborg Psalter, MS 1695, Musée Condé, Chantilly. See Florens Deuchler, Der Ingeborgpsalter (Berlin: De Gruyter, 1967), 97, 109n107, 113–14, 146, 148n238; and Tachau, ‘The King in the Manuscript’, 18n68, 19nn73–77, 20nn78–79.

[55] Tachau, ‘The King in the Manuscript’, 11.

[56] Martin Blindheim, ‘Scandinavian Art and Its Relations with European Art around 1200’, in The Year 1200: A Symposium, ed. Konrad Hofmann (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1975), 429–68.

[57] For another example of this combination of details, see the Deposition ivory discussed in Williamson, Medieval Ivory Carvings, cat. no. 104. The Deposition ivory has recently been acquired by the V&A: Inv. no. A.10-2024.