Cecily Hennessy and T. A. Heslop

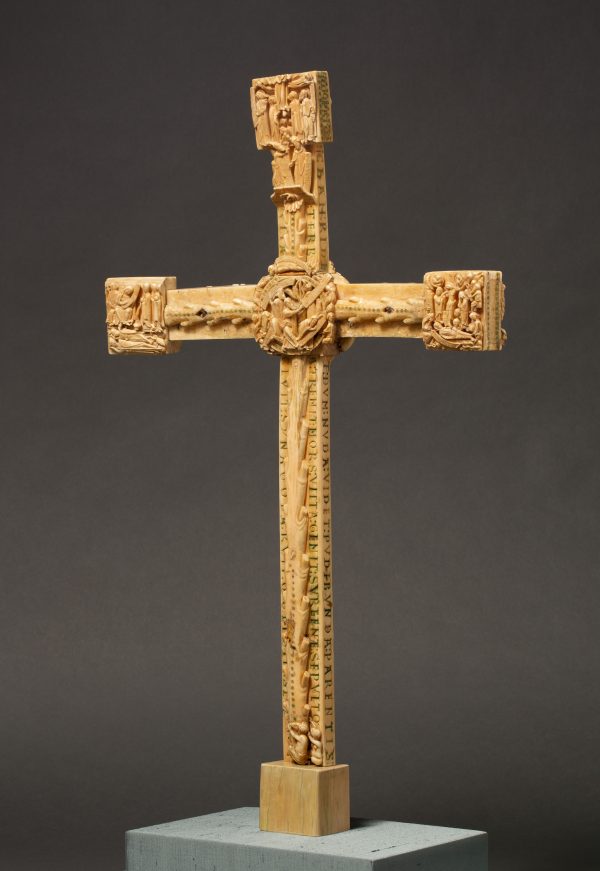

It is only rarely that a major work of art emerges from complete obscurity.1 Such was the fate of the of the walrus-ivory cross acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 1963, now generally known as the Cloisters Cross. In the same year, it was published in an article by Wiltrud Mersmann, the wife of its previous owner who went under the name Ante Topić Mimara (hereafter Topić, as he was generally known).2 Mersmann argued that the Cross originated in England in the middle decades of the eleventh century—which is to say before the Norman invasion of 1066 and the subsequent conquest of the English kingdom by William, duke of Normandy. While her suggestion of an English origin has been perpetuated in much of the later scholarly literature, the dating of the Cross to the pre-Conquest era has long been abandoned in favour of one a century or more later. The Cloisters Cross is now regarded as High Romanesque in style and exemplifying currents in the art of north-western Europe, including England but also other Latin-Christian polities north of the Alps. The place of the Cross’ production (and consumption) has included regions from northern France and the Low Countries to the Rhine Valley and Saxony, although England and Bury St Edmunds in particular still dominate in mainstream literature. The Metropolitan Museum of Art currently (2025) dates it to circa 1150–60 with a ‘British’ place of origin, while stating, ‘It has often been suggested that the cross comes from the English abbey at Bury Saint Edmunds in Suffolk’.3

The Cross’ transnational credentials are evident in both its visual imagery and the scholastic, almost encyclopaedic commentary on Christ’s crucifixion by means of biblical quotations which prophecy or reflect upon it. This was an era of intense biblical exegesis, especially in the ‘schools’ of northern France. By the mid-twelfth century, the focus was in Paris, though fuelled by earlier projects such as the compilation known as the Glossa ordinaria sometimes associated with Laon. But undertakings elsewhere by the likes of Honorius Augustodunensis (ca. 1080–ca. 1140), in England and southern Germany, and Rupert of Deutz (ca. 1075/1080–ca. 1129), in northern Germany were symptomatic of a general renaissance in biblical commentary, compilation, and analysis which is clearly registered in the texts inscribed on the Cloisters Cross.

Some of the visual and verbal rhetoric can be regarded as vehemently anti-Jewish. This is most obvious in the Latin verse (in large letters) on the side of the Cross claiming that ‘the Jews laugh at the pain of God’s death’ and the image of Synagoga piercing the Lamb of God in the central roundel on the reverse. Furthermore, the careful deployment of tall, conical hats to identify Jews in the various narrative carvings enabled the artist to participate in the business of defamation. This signifying tendency was particularly prevalent in the twelfth century in the parts of Europe where Romanesque art and scholasticism flourished. Words and images were accorded equal status and regarded as virtually interchangeable in the transmission of religious, Christian truths. Visions could be recorded in words or pictures, and though artists were not themselves visionaries or prophets, their job was to envisage and make visible the ideas of those who commissioned work from them. They developed a language of seeable signs that was as valid as any other means of communication. This was fundamental to the visual artist’s profession. Those who mastered this art were sought after by social and intellectual leaders as their publicists.

Approaches to the history of art are as prone to changing fashions as are the dynamics of art itself. Considering this ‘fact’ and the importance of the Cross and the many unresolved issues concerning it, we organised a workshop colloquium in May 2023, sponsored by the British Archaeological Association and the Courtauld Institute of Art. The aims were to revisit manifold issues: to explore new discoveries in walrus ivory as a medium for medieval objects; to consider how and why the Cross had been bought by the Metropolitan Museum of Art rather than another museum; to tackle once more the knotty problems of its dating and place of origin; and to discuss critical features of both the allusive texts displayed on it and the complex iconography.

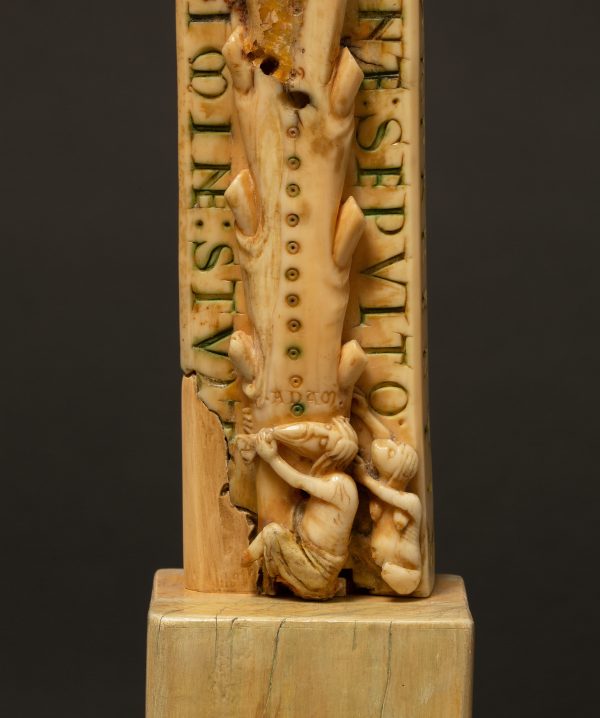

Although only just over fifty-seven centimetres high, the Cross is decorated with some 180 figures and inscriptions. These provide a wealth of detail, with both clear and veiled messages about Christ’s life and mission and contemporary attitudes towards believers and non-believers. The shafts of the Cross on the front depict the severed branches of the tree of the Crucifixion, while on the back is a series of Old Testament prophets, all with scrolls referencing their predictions and allusions (Figs. 1.1 and 1.2). The central roundel on the front includes most prominently a scene from the Old Testament: Moses and the Brazen Serpent (Numbers 21:5–9), a typological reference to the Crucifixion with added figures and inscriptions (Fig. 1.3). Above this scene is the dispute between Pilate and Caiaphas over the designation used for Christ in the titulus, which here reads ‘King of the Confessors’ rather than the otherwise ubiquitous ‘King of the Jews’. Above this, on the finial, is the Ascension (Fig. 1.4). On the two remaining front finials of the Cross are scenes depicting events of Christ’s Passion; the Deposition with the preparation for burial, known as the Good Friday plaque; and the Resurrection with the Maries at the tomb, known as the Easter plaque (Figs. 1.5 and 1.6). At the bottom of the cross shaft, above where a lost finial would be, are Adam and Eve (Fig. 1.7). On the back, in the centre, is a depiction of the Lamb of God, apparently having been pierced by Synagoga, a reference to Christ’s redemptive sacrifice and its rejection by non-believers (Fig. 1.8). On three finials (the bottom finial is again missing) are three of the Evangelists’ winged symbols: Mark’s lion, Luke’s ox and John’s eagle (Figs. 1.9–1.11).

In the first three essays in this volume, curators and scholars recall and reassess their knowledge of the Cross and revisit some of their earlier ideas about the object; these are followed by three longer research articles in which new ideas about the object’s origins and purpose are explored. There is no attempt here to present a single thesis or ‘answer’. The essays are offered together in the spirit of expanding the debate (both in content and audience).

Numerous publications on the Cross post-date the 1963 article by Mersmann.4 She had been working on this for several years, and, prior to its purchase by the Metropolitan Museum in early 1963, no photographs of the Cross had been made public. Mersmann assigned the Cross to eleventh-century Winchester, and it was this view that was disseminated by Topić in his attempts to sell it. He had probably owned the Cross from at least the early 1950s, perhaps from 1948, and it came discreetly on the market within a decade. Directors and curators from the Western world’s principal museums with medieval collections were interested in it, including the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the Cleveland Museum of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. A full account of the various negotiations between Topić and the museums has never been published, in part, perhaps, because the provenance of the Cross was always, and probably always will be, a secret. In his contribution here, Neil Stratford revisits the British Museum’s archives and his own recollections to reveal why the Cross was let go by the museum, despite the fact that many thought it should come to Britain, considering it was at the time largely agreed to be English.

The fullest discussion at the time was undertaken by a committee of specialists assembled to advise the Trustees of the British Museum. It comprised some dozen art historians, historians, and palaeographers with relevant expertise and the authority that went with it. Lists on file in the British Museum’s archives name those who should be approached, though it is not clear what the committee’s membership eventually was. It seems there was a meeting of the group, and the closest we get to a full list of participants is the signatures appended to the ‘minutes’, in effect a communiqué, signed in November 1962.5 It was clearly important that an agreed document should be authenticated by recognised experts. The committee members could not have seen the Cross itself, so their conversations were based on long-awaited photographs of it that had recently been given to the museum. There were further exchanges with the vendors who were then expected in London. It was mooted that Mersmann would offer a short article on the Cross to be published in The Burlington Magazine. But Rupert Bruce-Mitford, keeper of the Medieval and Later Antiquities Department at the British Museum, was not in favour, presumably because he thought the publicity would be unhelpful at this juncture.

It would be a digression too far to excavate what ‘English’ meant to the authorities who might grant the money to buy the Cross; suffice it to say that the committee came up with four reasons that the Cross was English. First, the ‘Lopped Cross’, that is to say, a cross shown as a tree trunk with severed branches, was widely represented in England in the eleventh and twelfth centuries (though details are not given). Second, the so-called Disappearing Christ at the Ascension was ‘virtually decisive’, referring to images in which only Christ’s lower legs are left visible while his upper body is engulfed by a cloud. Third, the ‘mummified’ body of Christ and its anointing were shown on the Good Friday plaque, and although no parallel was specified, examples such as the St Albans Psalter and the Winchester Psalter were well-known to both Francis Wormald and Otto Pächt.6 Finally, the ‘flamboyant’ use of scrolls was cited, with the Guthlac Roll of circa 1220 offered as a parallel, though other earlier instances could have been invoked.7 These can indeed be seen as justifying claims for the Cross’ English connections, but as the qualifier ‘virtually’ signals (in perhaps the least contentious instance, the Ascension), these claims are suggestive, not conclusive. Committee members would have been conscious that all these phenomena could be found on the Continent by the second half of the twelfth century, and in some cases earlier. Indeed, the Lopped Cross originated in the Carolingian empire at the time of Charles the Bald (ca. 860).8 There is perhaps a sense that the scholars involved found it easier to feel the work was English rather than wholeheartedly to believe it. Clearly, under the circumstances, any alternative propositions were not to be entertained. At the time, Winchester or Canterbury were discussed as places of origin, not Bury St Edmunds.9

But at least one expert could not attend the meeting and wanted amendments. This was T. S. R. Boase (then president of Magdalen College, Oxford). In the end he agreed to sign, despite expressed misgivings, because the important thing was unanimity. A note by Peter Lasko (then assistant keeper in the Department of British and Medieval Antiquities at the British Museum) in the museum’s files records that Boase ‘was not entirely convinced of the early date we would like, nor that it was English . . . but what he called ‘‘Channel School”,’ meaning if it were not English, certainly it was registering strong English influence in northern France or Flanders. He also thought the iconography ‘could be later twelfth century’.10 According to a note by Thomas Hoving (then curatorial assistant at the Cloisters), George Zarnecki (then deputy director of the Courtauld Institute of Art) thought the Cross was ‘possibly French’.11 Lasko himself may also have had doubts. In his book Ars Sacra, first published in 1972, he included the Cross in the chapter on ‘Lotharingia: Rainer of Huy’, locating it ‘between the Liège ivories and their English relatives’.12 Christopher Hohler (Courtauld Institute of Art), who was not on the committee, wanted the Cross for the British Museum, so decided to agree that it was English. As far as can be seen in the files, what that meant in the twelfth century in a recently conquered country in regard to the cultural and ethnic origins of patron, artist, or ‘learned adviser’ was never explored. This was an era in which there was a sense that there was an ‘Englishness of English Art,’ to quote the title of Nikolaus Pevsner’s broadcast lectures and much-reissued book first published in 1956, which adopted and supported the widespread idea that a work of art was supposed to embody national character. That was not necessarily presumed to be the result of the artists’ input: ‘If Holbein’s and Van Dyck’s English portraits look unmistakably English,’ it is because of ‘the actually English features and deportment of their sitters’.13

The committee, then, had done its job (so far as it was possible) to justify the Cross’ Englishness, if not to demonstrate that it was indeed English. But, in face of the fact that Topić would not or could not demonstrate his legitimate ownership of the object, the necessary funding from the Treasury was withheld. A sense of increasing desperation is evident in the British Museum documents from January 1963. Bruce-Mitford rehearsed some familiar arguments. If someone else had a claim on the Cross, why would Mersmann be publishing it? That would merely serve to advertise its present whereabouts and value. The Cross was both dirty and damaged when Topić acquired it, so it had not been a viable object for display or religious veneration for centuries. Fritz Volbach was apparently also shown one part of it in this state soon after the Second World War when he was living at the Vatican (working in its library and as a professor at the Papal Institute for Christian Archaeology), as he told Peter Lasko.14 Other points mentioned in the files could have been reiterated, such as the number of other objects bought and sold without any documentation deemed necessary. Perhaps it was the combination of the high price and the fact that Topić had worked at the Munich Central Collecting Point at the end of the war that principally troubled those in Whitehall.

Too much depended on assertion (oral transmission, memory) and trust. Even when things were written down, they could be altered, so, for example, in the British Museum’s files, Volbach’s name was first typed as Venturi, but corrected, and ‘Balkan’ as a potential provenance was supplemented by ‘Baltic’, subsequently explained as a possible mishearing.15 By early 1963, Baltic was the preferred alternative. Bruce-Mitford noted that ‘the Baltic provenance would be exactly right for an English object of this date’ and that Topić ‘said . . . he had a feeling that the fragments of the cross probably came from the Baltic states’. He also records that ‘its last change of hands was fifteen years ago. It was in 1948’.16 Bruce-Mitford does not mention, perhaps he did not know, that Topić was then in Munich.

By late February 1963, sale of the Cross to the Metropolitan Museum must have been effectively a done deal, but Topić continued to lead the British Museum on, suggesting it was still not too late. But it was. Whether the Treasury’s refusal to purchase the Cross was driven primarily by fear of complicity in the acquisition of a potentially looted work of art is not clear. Intriguingly, the latest communication on file in the British Museum is an email from Hoving, dated 30 March 2000.17 He wanted to see the museum’s dossier on the Cross in light of two recent publications by Jonathan Petropoulos: Art as Politics in the Third Reich and The Faustian Bargain.18 Hoving was apparently interested in pursuing the question of Topić’s career, having found out he was involved with ‘truly nasty things, like murder and dealing in Holocaust art’, and the reasons why the British Museum pulled out of the purchase of the Cross.19

The Cleveland Museum of Art had also been interested in purchasing the Cross. Sherman E. Lee (director, 1958–83) had been in touch with Topić at least since 25 August 1958, when Lee wrote to Topić that his predecessor, William Milliken (curator of decorative arts and director, 1930–58), had seen ‘some of your things’ in Zurich in 1956.20 By November 1959, when Lee met him in Paris, Topić had offered the Cross for the price of $750,000; Lee then wrote to him in January 1960 that ‘the cross of course is uppermost in our minds’.21 The dealer Harold Parsons acted as a go-between for Topić and Lee. In March 1960, Lee wrote to Parsons, ‘we are wildly enthusiastic’ but that the ‘crazy price’ needed to be ‘substantially modified’.22 The following month, Parsons wrote to Lee that Topić was hoping the Victoria and Albert Museum would find a donor to buy the Cross and urged Lee to make an offer; by July, Parsons told him that several museums, including the Musée du Louvre and the Boston Museum of Fine Arts were interested in it.23 When William Wixom (assistant curator/ curator of medieval and renaissance decorative arts, 1958–79) spent a day in Paris with Topić in November 1960, the price had come down to $500,000.24 By July 1961, Wixom wrote to Topić to say that Lee and the Trustees of the Cleveland Museum of Art could not consider purchasing the Cross that year and maybe not the next, and that ‘the price is too high’.25 This is later reiterated in a letter in November from Lee to Topić, saying he had discussed the Cross with the curators and decided it was too expensive.26 But was that the whole story?

By 1963, Hoving, now casting himself as the victorious purchaser after dallying with other views, became convinced the Cross was not eleventh but twelfth century and rather than from Winchester was from Bury St Edmunds. He published his justifications in 1964.27 His starting point seems to have been the similarities he identified between the Cross and illuminations in the Bury Bible, produced about 1135, a suggestion which was originally made by Harry Bober of the Institute of Fine Arts in New York in 1963.28 However, Hoving also linked the texts on the Cross to events in the 1180s and 1190s and so created a complex scenario in which the Cross was carved circa 1150 and the inscriptions added between 1181 and 1190.29 Hoving also published a gripping, but less than reliable, account of his achievement in securing the Cross for the Metropolitan Museum of Art.30 The more straightforward (and questioning) account of its purchase by funds from the Cloisters, where it is housed, is presented in this volume by Charles T. Little, who later succeeded Hoving as curator of medieval art and who co-wrote with Elizabeth Parker the substantial monograph on the Cross, published in 1994.31 Parker and Little’s book provides an extensive description and discussion of the iconography and inscriptions on the Cross. It largely supports the Bury St Edmunds attribution and a date in the mid-twelfth century while discussing and assimilating work published since 1964.32

Among the key publications Parker and Little revisited were three detailed articles by Sabrina Longland on the textual sources of the inscriptions and an analysis of some aspects of the imagery, all appearing in 1968–69.33 Aspects of the iconography included the use of the forked stick holding up the serpent raised in the wilderness by Moses, depicted on the front central roundel; the piercing of the Lamb of God by Synagoga, on the back central roundel; and the dispute between Caiaphas and Pilate over the naming of Jesus. Longland linked one of the couplets on the Cross with the widely disseminated work of scholars associated with the Victorines in Paris, a topic which she explores further here (writing as Sabrina Harcourt-Smith) in terms of the educational functions of the Cross.

The following year, in 1970, the Cross was a centrepiece in a seminal exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art titled The Year 1200.34 As Sandy Heslop explains in his essay here, the Cross was displayed with a corpus (body of the crucified Christ) brought to light in Copenhagen in 1884, which many by then considered original to the Cross. He goes on to develop significant connections between the Cross and Denmark. It is largely agreed that a corpus would have been attached to the Cross, but whether this has survived or been correctly identified is disputed. The Cross was also displayed with a panel depicting Christ before Pilate that was thought to be from the missing lower-front finial of the Cross. This small plaque first appeared at a sale in Paris in 1920 and was purchased by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1963. Like the Corpus, the panel is no longer attached to the Cross, though it might have been made either to replace a lost finial or as part of an accessory base. In a review of the exhibition, Willibald Sauerländer belittled the idea that either the Oslo Corpus or the Pilate plaque was made for the Cross.35 The Pilate plaque was later discussed in detail by Bernice Jones.36

In 1971, Rosalie Green, director of the Index of Christian Art, held a graduate seminar on the Cross at Princeton University and set the students the task of analysing aspects of its iconography. Several of them, including the architectural historian Stephen Gardner, who was then a student, concluded that it was of ‘Saxon’ origin, that is from northern Germany, and associated it with Henry the Lion. Gardner’s findings have not been published but are viewable in the Cloisters’ archive and discussed here in Hennessy’s essay, which also shows how Hoving and others had considered this option. Similar suggestions came to the fore in reviews of Parker and Little’s monograph. Heslop suggested that while ‘an English provenance for the Cross remains a possibility, its origin elsewhere, namely Germany, now needs to be acknowledged as more probable.’37 G. D. S. Henderson noted the many Continental parallels in Parker and Little’s book and wondered why the English connection had not been abandoned. He also suggested that the Cross had a relic on the front, rather than a corpus.38

In 1985 Ursula Nilgen focused on St Albans as the Cross’ place of origin and argued through stylistic comparisons that it showed French or ‘Channel Style’ influences, brought to England in the 1170s by Thomas Becket and his associates.39 This developed thoughts earlier espoused by Boase (see above) and subsequently endorsed by Stratford in a letter in The Burlington Magazine in which he summarised that the Cross ‘was carved in the third quarter of the twelfth century on one or the other side of the Channel’.40 For Boase and others, ‘Channel style’ expressed the character of manuscripts associated with Becket and Herbert of Bosham, produced by teams of scribes and illuminators whose origins, training, and places of work were no doubt varied. The term was also used, in a related context, by Walter Cahn in outlining the career of the so-called Simon Master, an illuminator employed by Abbot Simon of St Albans.41 His work is found in manuscripts made for patrons in England, France, and Denmark. While there is no reason to doubt that he travelled from place to place fulfilling commissions for wealthy institutions and individuals, we have no hard evidence regarding the formation of his style. In this respect he is paralleled by the artists of the Winchester Bible who possibly went from England to northern Spain to work on the chapter house at Sigena.42 The oeuvre of their contemporary, the metalworker Nicholas of Verdun, also comprises important projects in various European centres, at Klosterneuburg (near Vienna), Cologne, and Tournai. The demand for talented and prestigious artists was an important element in disseminating Romanesque and (later) Gothic art and architecture, giving these styles international currency in Latin Europe and making the quest for origins perilous. Is the answer to the context of the Cross’ manufacture to be found among artists and their styles, theologians and their ideas, or the meeting of the two? A brief article by John Munns set out some comparisons with the Stammheim Missal made at St Michael’s Abbey in Hildesheim in the 1170s, which could be seen to work in both respects.43 However, it elicited a ‘pro-Channel School’ response in support of Nilgen’s proposal.44 Less ambiguously, the belief that the Cross is in some real sense English persists. Rainer Kahsnitz, in his Goldschmidt Addenda volume, published in 2022, assigns both the Cross and the Pilate plaque to ‘England, 3. Viertel 12. Jahrh.’ (third quarter of the twelfth century).45

The varying, indeed fluctuating, opinions about the Cloisters Cross complicate attempts to localise its production and consumption. Stylistic analysis only goes so far: even if the Simon Master or any other ‘Channel’ artist had predilections like those of the artist of the Cross in regard to figure gestures and poses, facial types, and drapery arrangements, that indicates little more than a general, elite, ‘international’ milieu in the second half of the twelfth century.

One topic that has never been explored at length is the material aspect of the Cross. In her contribution here, Robyn Barrow gives a fresh understanding of medieval trade in walrus ivory, how it was collected and transported, and how the Cross fits within the wider sphere of Arctic ivory in the Middle Ages.

We hope that the essays in this collection will stimulate discussion and promote awareness of the Cross and its seemingly unique potential for developing our thinking about medieval culture in the decades before and around 1200. In revisiting its past and complex and (perhaps intentionally) obscure history on the art market; looking at reminiscences about the purchasing dilemmas faced by the Western world’s leading museums; and summarising subsequent scholarship and the unravelling of possibly hastily made attributions and the Cross’ interpretation, this book hopes to dilate the questions and perceptions of the provenance and the meaning of this singular object.

Citations

[1] We would like to thank the British Museum for giving us access to their archives on the Cloisters Cross. Cecily Hennessy would also like to thank the Society of Antiquaries for a Philips Grant for research in the United States; and the Cleveland Museum of Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Cloisters for generous use of their archives.

[2] Wiltrud Mersmann, ‘Das Elfenbeinkreuz der Sammlung Topić-Mimara’, Wallraf-Richartz-Jahrbuch, 25 (1963): 7–108.

[3] ‘The Cloisters Cross’, The Met Collection, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/470305.

[4] Mersmann, ‘Das Elfenbeinkreuz’.

[5] See ‘Romanesque Ivory Cross Reporting Committee’, GR. NO. 351/62, Bury St Edmund Ivory Altar Cross (Offered by Ante Topic Mimara), Correspondence 1960–Jan. 1963, BEP, Potential Purchases, British Museum Archives, London. The signatures include those of Peter Lasko, George Zarnecki, Francis Wormald, Derek Turner, Hugo Buchthal, and Otto Pächt.

[6] The St Albans Psalter (now Dombibliothek Hildesheim HS St. God. 1, Cathedral MS 1, p. 48), shows the mummified body and a man holding a vial, and the Winchester Psalter (BL Cotton MS Nero C IV, f.23) shows the anointing and Christ’s body ‘in grave clothes’. See Otto Pächt, C. R. Dodwell, and Francis Wormald, The St. Albans Psalter Albani Psalter: 1. The Fullpage Miniatures by Otto Pächt; 2. The Initials, by C. R. Dodwell; 3. Preface and Description of the Manuscript, by Francis Wormald, Studies of the Warburg Institute 25 (London: Warburg Institute, 1960); and Francis Wormald, The Winchester Psalter: With 134 Illustrations (London: Miller & Medcalf, 1973), published posthumously.

[7] See Guthlac Roll, MS Harley Roll Y 6, British Library, London.

[8] As on the ivory cover of the Codex Aureus of St Emmeram, Clm 4452, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich. See Jennifer O’Reilly, ‘The Rough-Hewn Cross in Anglo-Saxon Art’, in Ireland and Insular Art AD 500–1200, ed. Michael Ryan (Dublin: Royal Irish Academy, 1987), 153–58; and John Munns, Cross and Culture in Anglo-Norman England: Theology, Imagery, Devotion (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2016), 116–20.

[9] As noted in a letter from Jack Schrader (then curator at the Cloisters) to James Rorimer, 8 January 1963, reporting a conversation with Rupert Bruce-Mitford, in Cloisters Cross, file 1, Correspondence 1956–April 1963, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

[10] T. S. R. Boase, English Art, 1100–1216 (Oxford: Clarendon, 1953, repr. 1968), 162, mentions the Cross only in a footnote referring to Thomas P. Hoving and James J. Rorimer, ‘The Bury St. Edmunds Cross’, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 22, no. 10 (1964): 317–40: ‘Ingenious as are his arguments, it must be remembered that the association with Bury rests upon stylistic resemblances that cannot be held entirely conclusive’.

[11] The date and full quotation are given in Cecily Hennessy’s essay in this volume.

[12] Peter Lasko, Ars Sacra, 800–1200 (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1972), 168.

[13] Nikolaus Pevsner, The Englishness of English Art: An Expanded and Annotated Version of the Reith Lectures Broadcast in October and November 1955 (London: Architectural Press, 1956), 198.

[14] Related by Peter Lasko in conversation with Heslop in the early 1980s.

[15] See Bury St Edmund Ivory Altar Cross (Offered by Ante Topic Mimara), Correspondence 1960–Jan. 1963, BEP, Potential Purchases, British Museum Archives, London.

[16] Letter from Bruce-Mitford to Sir Frank Francis, 17 January 1963, Bury St Edmund Ivory Altar Cross (Offered by Ante Topic Mimara), Correspondence 1960–Jan. 1963, BEP, Potential Purchases, British Museum Archives, London.

[17] Copy of email from Thomas Hoving to Suzanna Taverne (managing director of the British Museum), 30 March 2000, secretariat file no. A 45/51/114, BEP, Potential Purchases, British Museum Archives, London.

[18] Jonathan Petropoulos, The Faustian Bargain: The Art World in Nazi Germany (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000); and Jonathan Petropoulos, Art as Politics in the Third Reich (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996).

[19] See email from Thomas Hoving to Suzanna Taverne, 30 March 2000, secretariat file no. A 45/51/114, BEP, Potential Purchases, British Museum Archives, London.

[20] Letter from Sherman Lee to Ante Topić Mimara, 25 August 1958, no. 3, Topić-Mimara, A., 1958–1965, Sherman E. Lee, box 70, Cleveland Museum of Art Archives, Cleveland, OH.

[21] Offering price quoted in a letter from Harold Parsons to Sherman Lee, 12 November1959, no. 3, Topic-Mimara, A., 1958–1965, Sherman E. Lee, box 70, Cleveland Museum of Art Archives, Cleveland, OH. Parsons also listed those who had seen the Cross: Fritz Volbach, John Pope Hennessy, Richard Randall, Georg Swarzenski. See letter from Sherman Lee to Ante Topić Mimara, 6 January 1960, no. 3, Topic-Mimara, A., 1958–1965, Sherman E. Lee, box 70, Cleveland Museum of Art Archives, Cleveland, OH.

[22] Letter from Sherman Lee to Harold Parsons, 3 March 1960, no. 3, Topic-Mimara, A., 1958–1965, Sherman E. Lee, box 70, Cleveland Museum of Art Archives, Cleveland, OH.

[23] Letter from Harold Parsons to Sherman Lee, 13 April 1960, no. 3., Topic-Mimara, A., 1958–1965, Sherman E. Lee, box 70, Cleveland Museum of Art Archives, Cleveland, OH; and letter from Parsons to Lee, 6 July 1960, in the same file.

[24] Letter from Harold Parsons to Sherman Lee, 18 November 1960, no. 3, Topic-Mimara, A., 1958–1965, Sherman E. Lee, box 70, Cleveland Museum of Art Archives, Cleveland, OH.

[25] Letter from William Wixom to Ante Topić Mimara, 17 July 1961, no. 3., Topić-Mimara, A., 1958–1965, Sherman E. Lee, box 70, Cleveland Museum of Art Archives, Cleveland, OH. Wixom gives the price then as ‘200,000 Pounds’.

[26] Letter from Sherman Lee to Ante Topić Mimara, 22 November 1961, no. 3, Topic-Mimara, A., 1958–1965, Sherman E. Lee, box 70, Cleveland Museum of Art Archives, Cleveland, OH.

[27] Hoving and Rorimer, ‘The Bury St. Edmunds Cross’, 339 (dating summary). The foreword to this article is by Rorimer, then director of the museum. For Hoving’s earlier thoughts, see the quotation in Cecily Hennessy’s essay in this volume.

[28] Kay Rorimer, ‘Trésor de l’art roman anglais: La croix du Cloister à New York’, Estampille, February 1988, 54. See also Bury Bible, 1121–43, MS 2, Corpus Christi College, University of Cambridge, Cambridge; and Hoving and Rorimer, ‘The Bury St. Edmunds Cross’, 334–36, figs. 22, 25–27, 29, 33.

[29] Hoving and Rorimer, ‘The Bury St. Edmunds Cross’, 339.

[30] Thomas Hoving, King of the Confessors (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1981).

[31] Elizabeth C. Parker and Charles T. Little, The Cloisters Cross: Its Art and Meaning (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1994).

[32] Parker and Little, The Cloisters Cross, esp. 197–277.

[33] Sabrina Longland, ‘Pilate Answered: What I have Written I Have Written’, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 26, no. 10 (1968), 410–29; Sabrina Longland, ‘The “Bury St. Edmunds Cross”: Its Exceptional Place in English Twelfth-Century Art’, The Connoisseur 172 (1969): 163–73, figs. 6–9, 13, 16, 20; and Sabrina Longland, ‘A Literary Aspect of the Bury St. Edmunds Cross’, Metropolitan Museum Journal 2 (1969): 45–74.

[34] Konrad Hoffmann, The Year 1200: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, February 12 to May 10, 1970 (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1970).

[35] Willibald Sauerländer, ‘“The Year 1200,” a Centennial Exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, February 12–May 10, 1970’, The Art Bulletin 53, no. 4 (1971): 506–16.

[36] Bernice R. Jones, ‘A Reconsideration of the Cloisters Ivory Cross with the Caiaphas Plaque Restored to Its Base’, Gesta 30, no. 1 (1991): 65–88.

[37] T. A. Heslop, Review of The Cloisters Cross: Its Art and Meaning, by Elizabeth C. Parker and Charles T. Little’, The Burlington Magazine 136, no. 1096 (1994): 459–60.

[38] G. D. S. Henderson, Review of The Cloisters Cross: Its Art and Meaning, by Elizabeth C. Parker and Charles T. Little’, The English Historical Review 111, no. 444 (1996): 1240–41.

[39] Ursula Nilgen, ‘Das Große Walroßbeinkreuz in den “Cloisters”’, Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 48, no. 1 (1985): 39–64.

[40] Neil Stratford, ‘The Cloisters Cross’, The Burlington Magazine 156, no. 1336 (2014): 464.

[41] Walter Cahn, ‘St. Albans and the Channel Style in England’, in The Year 1200: A Symposium, ed. Konrad Hoffmann (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1975), 187–230. For the phenomenon, see also Christopher de Hamel, Glossed Books of the Bible and the Origins of the Paris Booktrade (Woodbridge: Brewer, 1984).

[42] Walter Oakeshott, Sigena: English Romanesque Paintings in Spain and the Winchester Bible Artists (London: Miller and Medcalf, 1972), following Otto Pächt, ‘A Cycle of English Frescoes in Spain’ The Burlington Magazine 103, no. 698 (1961), 166–75. For a recent assessment of this, see Neil Stratford, ‘The Hospital, England and Sigena: A Footnote’, in Romanesque and the Mediterranean: Points of Contact across the Latin, Greek and Islamic Worlds c. 1000 to c. 1250, ed. Rosa Bacile and John McNeill (Abingdon: Routledge, 2018), 109–16.

[43] Stammheim Missal, MS 64, J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, CA. See John Munns, ‘Relocating the Cloisters Cross’, The Burlington Magazine 155, no. 1323 (2013): 381–83.

[44] See Stratford, ‘The Cloisters Cross’.

[45] Rainer Kahsnitz, Goldschmidt Addenda: Nachträge zu den Bänden I–IV des Elfenbeincorpus von Adolph Goldschmidt, Berlin 1914–1926, Sonderucke aus der Zeitschrift des Deutschen Verein für Kunstwissenschaft 68, 72/73 (Berlin: Deutscher Verlag für Kunstwissenschaft, 2022), nos. 155–56.