Kinga Bódi, PhD, is curator at the Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest. As a doctoral fellow at the Swiss Institute for Art Research (SIK–ISEA) she investigated the cultural representation of Hungary at the Venice Biennale from its beginnings until 1948. In her present essay, Bódi jointly discusses the first contemporary avant-garde Hungarian show in Venice in 1928 and the Biennale edition of 1948, which she interprets as a counterpoint of sorts to the one twenty years earlier, defined by conservative ideological principles and neo-Classicism. Her study examines the historical, social, cultural, political, artistic, professional, and personal background of these two specific years of Hungarian participation in Venice. At the same time, her essay contributes to current international dialogues on the changing role of international exhibitions, curatorial activities, and (museum) collections. (BH)

Looking Forwards or Back? Shifting Perspectives in the Venice Biennale’s Hungarian Exhibition: 1928 and 1948

Kinga Bódi[1]

From 1895 to 1948, it was self-evident that Hungary would take part in the Venice Biennale. During this period, the country too kept in step, more or less, with the artistic and conceptual changes that governed the Biennale, virtually the sole major international exhibition opportunity for Hungarian artists then and now. This is perhaps why, for the 124 years since the first participation, the question of the Hungarian Pavilion has remained at the centre of domestic art-scene debates.

Comparing nations has always been a facet of the Venice Biennale. In Hungary’s case, this comparison took place on a variety of planes. In the early years, during the era of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy, Hungarian exhibitions were defined by cultural rivalry with the Austrians.[2] As cultural politicians came to comprehend the potential of the Biennale to shape the national image, the relevance of Hungarian participation and, with it, political interference in the selection process became greater. Hungary first took part in Venice independent from the Austrians in 1901. The separate Hungarian Pavilion, built in 1909, represented the apex of this process of separation and self-positioning. The Pavilion was remarkable not just for its size, patriotic decorations and building costs totalling two hundred thousand crowns (with which it remained the most expensive Giardini pavilion of the pre-First-World-War era), but also because it was erected twenty-five years earlier than the autonomous Austrian Pavilion that first opened in 1934.

After 1918, international recognition and the maintenance of a positive image abroad were of paramount importance for Hungarian political leaders. The Italian host’s positive attitude towards Hungary and Hungarian art helped make the Biennale the major international forum to showcase Hungarian art. Italian-Hungarian political relations continued to fundamentally define Hungary’s participation and Hungarian success in Italy in the interwar years. Nevertheless, the changes in Italian politics after the summer of 1943 (the overthrow of Benito Mussolini, the formation of the Salò counter-government, and finally the country turning against its former ally Germany) indicate that Hungarian political leaders frequently deluded themselves thinking that Hungary was anything more than just one player within broader Italian aspirations in Central Europe. In the light of the above, it is difficult to assess realistically the goings-on in the realm of art. Dismissing Italian enthusiasm for Hungarian art as mere political tool is just as one-sided and incorrect as an uncritical acceptance of their ‘adoration’. In any case, the truth lies somewhere in the middle, between political interests and the appreciation of genuine artistic quality. To take but one example, the fact that Benito Mussolini awarded the first prize of the 1940 Biennale to Vilmos Aba-Novák’s painting The Village Festival (Lacikonyha) neither detracts from the work’s artistic merit, nor adds to it.

Undoubtedly, the 1909 Pavilion was the greatest sensation in the entire history of Hungarian participation. The building was devised by architect, sculptor, interior and industrial designer Géza Maróti, the most sought-after ‘pavilion designer’ of his age, who had planned countless Hungarian exhibition halls at various international exhibitions (Fig. 17.1). (These included the internationally-successful Pavilions at Turin in 1902 and Milan in 1906.) The Hungarian Pavilion was the second to be built after the Belgian one in 1906; its early construction date and distinguished position in the vicinity of the Central Pavilion offer examples of how political relations were mapped onto the Giardini. Austrian-Hungarian rivalry notwithstanding, Italy also had close relations with Austria. Hungary and Italy struggled for similar goals—achieving national independence and ending Habsburg oppression—and thus Hungarian-Italian friendship was strengthened by sharing an ‘opponent’. The concrete outcomes of this alliance were often seen at the Biennale, with Italian public and private collectors purchasing Hungarian works, and the publication of exorbitantly positive reviews of Hungarian exhibitions.

Hungary’s political relations and geopolitical situation underwent many transformations until the early 1950s.[3] Although exhibiting artists and exhibition organisers altered over the years, nothing fundamentally changed as far as the general outcome and operational mechanisms were concerned. Indecision, conflicts of interest, late-stage flip-flopping, hasty preparations, and professional incompetence remained constant over the decades. Events were only successful when a good professional happened to be in charge. Although Hungary regularly took part in the Biennale, no standard procedures were in place: they participated sometimes with a curator, sometimes without; sometimes with an artistic director, sometimes without. Lacking any clear decision on who was responsible for selecting the materials, it seemed that Hungarian leaders were surprised each time an exhibition had to be organised. Only in a few instances was there any precise artistic or cultural policy concept concerning participation in Venice.

Hungarian exhibitions were, especially after the First World War, essentially determined by conflicts of interests between artists. The official leadership could have had the power to solve these conflicts, yet given the lack of a definite, comprehensive Biennale concept, no ‘good’ solutions were ever found. While a small number of works (more) in sync with contemporary trends somehow ended up on show, Hungary usually represented itself with retrospective selections and national-themed works: the countryside, portraits of the elite, and so on. Although Biennale organisers expected the inclusion of both most recent works and overviews of past achievements, Hungary tended to accomplish only the latter.

Following the 1926 Biennale, the art historian and liberal art critic Máriusz Rabinovszky summarised his impressions in Nyugat (West), diagnosing the ills of the age in his article ‘The Stagnation of Artistic Life’:

Ignorance and a degree of cluelessness in artistic life are a global phenomenon … Yet there are certain aggravating circumstances peculiar to Hungary I would like to address. Our artists do not form groups according to their inner artistic orientation; they have no shared platform as a group. The life-giving struggle of ideas is absent. The audience is disorganised and ignorant, largely capricious and thus reluctant to either acknowledge or dismiss. Criticism too generally functions without definite points of view. Acknowledgement is granted to everyone, and hardly anyone expresses themselves for or against this or that idea. Our art trade is insignificant, our exhibition halls function haphazardly or based on prestige. Our authorities engage in diplomacy without any concepts at all, driven instead by personal opinions.[4]

Rabinovszky regarded the lack of a struggle of ideas between the generations and particular camps as the greatest problem.

The problem underlying exhibitions organised both at home or abroad was that fine arts had actually ceased to be a public concern, as Rabinovszky asserted in his text. Whenever a Hungarian year in Venice was relatively successful, there was not necessarily a well-thought-out plan in the background, but rather an outstanding artist or theorist who had ‘accidentally’ landed in the directorial position. One such positive exception to the rule was the exhibition of 1928, conceived and organised by János Vaszary. Vaszary, himself an artist, was a pro-modern advocate of progressive artistic tendencies, a key figure in the Hungarian art world respected for his creative work and teaching activities. No wonder therefore that the most discussed exhibition of the interwar years was, in the domestic context, this ‘Vaszary Biennale’, one of the most successful and most modern Hungarian exhibitions of the pre-1948 period and, at the same time, the show most loudly criticised by the Hungarian authorities.[5]

János Vaszary and the Students (1928)

It is possible that Vaszary was appointed to this role because, in 1924, the then Minister for Religion and Public Education, Count Kunó Klebelsberg, had spoken approvingly of his art. Klebelsberg was a defining figure of Hungarian cultural policy in the 1920s who, despite his essentially conservative outlook, advanced many progressive cultural development measures. In 1926, Vaszary had criticised the Hungarian display in Venice, and this may be why Klebelsberg granted him, a Hungarian Academy of Fine Arts lecturer acknowledged as the leader of free-thinking education, the opportunity to choose who should be exhibited and represent the country in the international realm.

It is worth mentioning here another article by Máriusz Rabinovszky, published in 1928, on the system of exhibition applications and judging.[6] For Rabinovszky, the greatest problem was that juries generally consisted of artists who could not possibly remain objective, leading to a lack of appropriately qualified, informed, and unbiased art critics or experts on the juries. He felt that a better solution would be:

to appoint a commissioner with full powers alongside a council of experts. This one individual would be responsible for all decisions, although of course only morally responsible. At the same time, he would take advice from a range of experts, artists, technicians and public figures. Yet this decision would alone belong to him, the appointed art expert, who is neither a practicing artist, nor someone bound by their official post, nor a layman. The advisory body would consist of representatives from the broadest range of artistic currents, who argue in favour of their selection to the unbiased expert. Thus, it would not be a majority that decides, but the better argument.[7]

Rabinovszky considered this ‘all-powerful commissioner system’ valid not only for the applications process, but also for the organisation of all publicly funded domestic and international exhibitions, as well as state purchases. In the debates over applications and international exhibitions, he viewed the greatest problem as the lack of ‘shared taste, shared culture, common spirit and a shared worldview’ within the Hungarian scene.[8] Rabinovszky’s model was ahead of its time, and to this day, his proposition has only been applied in a very small number of cases. The position of the all-powerful art-expert commissioner did in fact take shape by the mid-1930s, but was not complemented by an advisory body, and thus a series of one-sided, authoritarian decisions unfolded which would remain in place for decades.

Vaszary was granted full powers in 1928: he was chair of the exhibition committee, the artistic director and organiser of the show, as well as an exhibiting artist, but as such, did not quite qualify as ‘objective’ either. He preferred to exhibit works by his own students, most of whom had ‘already moved beyond naturalist depiction and sought to connect with the new formal experiments of the time’.[9] In addition to works by his students and modernism-oriented painters and sculptors, Vaszary also selected fifteen paintings and fourteen watercolours and pastels of his own as a small individual show. The exhibition enjoyed great international success, receiving particularly high praise in the Italian daily papers who commended the show in its entirety and the new emerging artists.[10] None of the Hungarian artists who took part in the 1926 Biennale were re-invited by Vaszary in 1928. The latter exhibition featured a completely new selection, a completely different segment of Hungarian art in Venice: these were ‘rougher’ works showing new spatialities with looser brushwork, painted by more open-minded artists who had abandoned the attempt to imitate the world, striving instead for a more ‘abstract’ sort of vision.

Ugo Nebbia, a leading Italian art critic of the time, dedicated six pages to introducing and appraising the Hungarian artists in his book The Sixteenth International Art Exhibition in Venice (La XVI Esposizione Internazionale d’Arte Venezia).[11] Despite the decidedly-subjective reference to ‘my Hungarian friends’ with which Nebbia opened the piece, his text can be regarded as a valuable, critical document of the time. Nebbia too welcomed the exhibition’s narrower focus on one group of ‘lively avant-gardists’ over a comprehensive attempt to give a full overview. Coordinated ‘in the spirit of the new’, the Hungarian exhibition was brave and unified, which Nebbia felt paralleled the spirit of the Biennale. He called Vaszary a ‘trendsetter’, a ‘most forceful voice’ whose influence defined the works by other Hungarian artists both spiritually and physically, (given that the main wall of Hungarian Pavilion’s central lounge only featured pictures by Vaszary) (Fig. 17.2). Nebbia identified Henri Matisse as a source of inspiration for Vaszary, whose painting was also influenced by his time in Paris (illuminated backgrounds, more relaxed brushwork, and enhanced expression), yet he also declared him to be a great individual personality who was able to maintain a distance from Matisse. Vaszary’s fiery colours stemmed, as it were, from the Hungarian’s character and not exclusively from Parisian influence.[12] Nebbia emphasised that all the Hungarian artists had been influenced by Paris, but then swiftly moved to point out the distinctive, un-Parisian, ‘Hungarian’ character of some. At times, he contradicts himself by stating that the Hungarians were merely ‘Paris-epigones’, yet then again, that they also created their own style beyond Paris. Nebbia clearly regarded Vaszary as the most unique of all, able to reconcile ‘sudden objectified visions and elements of reality’ in his ‘skilful robust brushwork’, astonishing the viewer with the ‘swiftness of his brushwork and the freshness of his colour and expression’.[13] With respect to Vaszary’s students, Nebbia placed stronger emphasis on their pursuit of certain patterns. Vilmos Aba-Novák was a ‘sensitive colourist’; József Egry’s works were imbued with Cubist expressivity but nevertheless distinctive; while Ödön Márffy followed the trail of Constructivism. He highlighted Károly Patkó’s ‘weighty nudes’ and ‘humble landscapes’, emphasising the artist’s rich colour palette throughout these different forms of depiction. Nebbia termed Károly Kernstok’s art unclassifiable, praising his diverse modes of expression, weighty shapes and facture. Róbert Berény’s 1928 painting Woman Playing the Violoncello (Csellózó nő) was awarded special praise (Fig. 17.3). Of the painters, Nebbia found Pál Molnár C.’s depictions and Jenő Medveczky’s religious paintings the least convincing. He addressed works on paper (watercolours and pastels) separately, declaring the entire section animated and expressive. After examining the sculptural works, he turned to the applied arts section which he described as ‘full of life’, emphasising the ‘popular Expressionism’ and wit realised in the various tapestries and maiolicas.

The reaction from domestic anti-liberal academician circles to the compilation of ‘new’ Hungarian works at the 1928 Biennale was predictable. Oszkár Márffy, a conservative literary historian, expert on Italian-Hungarian cultural relations and respected university lecturer, only gently criticised Vaszary’s exhibition, noting that although he had ‘presented a prestigious collective series’, ‘this exhibition, while designed to be representative, omits countless outstanding values of our art’.[14] Far harsher criticism came from Nándor Gyöngyösi, editor of the Képzőművészet (Fine Art) journal (the arbiter of official artistic taste), in his letter to K. Róbert Kertész, one of Klebelsberg’s closest men and head of the Art Department at the Ministry of Religion and Public Education. Kertész was, in other words, the highest-ranking cultural official at the time who was, until 1934, responsible for overseeing the Hungarian participation in Venice. Gyöngyösi was outraged that the Hungarian Pavilion featured exclusively the ‘extremist, newest Hungarian art’, and asked that the minister bring an immediate end to this one-sidedness.[15] In Gyöngyösi’s view, only two smaller groups, the young Academy of Fine Arts students and the Pál Szinyei Merse Society, who represented a distinctly liberal, middle-class antidote to the art favoured by the state, were granted a larger platform at international exhibitions, even though they were the smallest in number. In other words, Hungarian art exhibitions abroad were the least representative of Hungarian art as a whole.[16] Led by himself and painter Imre Knopp, academician artists demanded that the National Arts Council of Hungary International Exhibitions Executive Committee undertake ‘reforms’ aimed at eliminating the ‘one-sided composition of the jury’.[17]

It transpires from Knopp’s letter, and the subsequent amendments to the original list of works submitted for the Biennale, that the academic conservatives wanted to change the contents of the exhibition until the very last minute. While it is possible that a few items were indeed not included as a result of their vehement protest and pressure, they failed to change the overall composition of the 1928 exhibition. It remains unclear whether it was the National Arts Council of Hungary or Vaszary who yielded to this pressure to modify the exhibition. Knopp wrote: ‘I find it pertinent to mention that certain mistakes were made concerning the Venice exhibition; I only need mention that the Ministry had to implement certain corrective measures in Venice which, however, could no longer produce the requisite result’.[18] After the Biennale and the 1928 exhibition of Academy students at the Budapest Kunsthalle, attacks against Vaszary intensified. No voices of defence could make themselves heard, even if the views expressed were far from being ultramodern, like this opinion published in the daily Pesti Napló (Pest Journal): ‘We must do away with the outmoded and obstinate belief that the artist can only become ‘established’ at a certain age, having traversed a bitter path of disappointments and blunders! The most certain promise for the art of the future is always the strong and dynamic talent of youth’.[19] Under constant attack, Klebelsberg and K. Róbert Kertész yielded to pressure, announcing that ‘students and extremists’ would not be included in large Hungarian exhibitions abroad.[20] The upshot was that János Vaszary was forced into retirement in 1932 for supporting his students who endorsed progressive art and cultural openness.[21]

For the purposes of comparison, it is worth examining which artists featured in other countries’ pavilions at the time when Vaszary’s selection was subjected to harsh criticism in Hungary. The German Pavilion held large, monographic retrospectives for the two greats of Expressionism, Franz Marc and Emil Nolde, as well as for Lovis Corinth. Also on show were representatives of Die Brücke and Der Blaue Reiter groups, including Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Max Pechstein, and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff.[22] The French Pavilion dedicated a retrospective to Paul Gauguin alongside paintings by Henri Matisse and sculptures by Antoine Bourdelle. The Dutch Pavilion featured works by Piet Mondrian. The Italians organised a comprehensive exhibition of Ottocento art and dedicated a special exhibition space to the Futurists. Der Cicerone’s critic singled out Hungary and Holland as joyful exceptions to the average that year: both placed ‘young art at the forefront’ of their Pavilions. He regarded the Swiss, American, Romanian, Swedish, and Austrian Pavilions as the most underdeveloped.[23] The critic from the London-based The Studio was less enthusiastic about the Hungarian section. Acknowledging that the artists themselves were good, highlighting Kernstok and Vaszary in particular, he nevertheless noted with regret that in his opinion, all in all they were unable to break away from the French model, and as a result, their works did not truly express a Hungarian spirit.[24]

On this note, it is worth briefly turning to the dichotomy of the fundamental duality underlying the Venice Biennale as cultural phenomenon: it is a platform for both exhibition technical internationalism and cultural regionalism. Since its founding, the Biennale has pursued a shared (Western, later global) standard and, at the same time, aspired to offer a framework for the presentation of specific, distinct national characters and ‘styles’. To this end, an international biennial exhibition of separate national participants was created—the only international mega-exhibition to preserve this structure to this date. The Venice Biennale therefore has represented a form of ‘bridge’ providing an opportunity to lift regional works into an international context, thus placing local artistic particularities in broader perspective. However, for over a hundred years, the duality of internationalism and national distinction has not always remained static, oscillating between contradiction and harmony. For example, Italian art was over-represented during the Biennales of the Fascist era, during which a clear differentiation between national arts was also an express aim. With the current dominance of thematic shows (Arsenale, Central Pavilion, external pavilions and the eventi collaterali, and so on), it is the international, global character of the Biennale that prevails. Italy’s attitude towards the Biennale has also changed over the decades: while the 1895 Biennale aspired to emphasise and ameliorate the situation of Italian art, placing it in the international canon, the concept of today’s organisers is, conversely, that Italian art should be presented on much smaller terrain in comparison to other countries.[25] Although the Biennale was ‘international’ in name at the time of its founding, this internationalism was, for a long time, only understood as referring to Western Europe and the United States, within which the ‘European track’ dominated: from 1895 to 1952, only European artists were awarded the Biennale prize. The presence of non-European artists only really gained strength after the Second World War, and continues to grow from year to year.

The 1928 Biennale still offered a survey in which the art of the past dominated, with a view, however, to retrieve modernity in the past. Meanwhile, Antonio Mariani and Benito Mussolini wanted to foreground the art of the ‘new Italian future’ both in the Giardini and across Italy.[26] The contradiction and struggle between the easy, viewer-friendly salon art of the past, and a combative, more opaque Futurist art also intensified at the Biennale. Vaszary himself reported on the Biennale as a whole, the various national exhibitions, and the opposition between academy and modern art:

When we walk through the glassy pavilions of the Giardini Publici [sic], … calm, balanced academy forms are disrupted by the restless experiments of modern man, flowing around the foundation stone for a new art world. The neat rows of works have been unsettled. By raising a new question, the Venice Biennale has tried to surgically rejuvenate flabby, ageing, repetitive and self-regarding conservative art. They wanted to see a progressive, modern art.[27]

At the same time, Vaszary set out why the Biennale cannot possibly succeed in presenting only the most progressive art, despite all efforts. He located the problem in the enormous exhibition space which was impossible to fill every two years with exclusively modern, high-quality works. Thus the ‘art of the last century’ also had to be always invoked, next to which ‘we are happy to welcome an emphasis on the modern as the indisputable force and urgent present of this art’. Next, Vaszary listed the more important exhibitions:

From the Academy students to Novocento and the Futurists, the Italian initiative and achievement is so absorbing that it can make its own individual dynamics felt, which is frequently different and independent from the methods and foundations of Europe … The French pavilion was directed by Massan, the conservationist at the Luxemburg art gallery. It is unlikely he selected the pictures himself; these are hung in typical museum style where everything is explained and nothing is emphasised. The museum of modern painting … The British remain inside their own world of conservative taste … The German pavilion, like the Hungarian, emphatically stresses progressivity. Painters were grouped according to school … Emil Nolde, displayed with a collection of works, represents the most extreme painting, seeking strong impact with his exaggerated forms and dazzling, decorative colours … Although they had authoritative, progressive works at their disposal, the Dutch preserved the impression of conservatism by way of the show’s arrangement.

Vaszary then turned to the Belgians (‘clearly bringing Naturalists who remind us of the French’), the Spanish (‘as if they knew nothing of what sparks interest in painting today’), the Czechs (‘who exhibited etchings reminiscent of Rembrandt, but otherwise had nothing to do with new art’), and the Russians (‘the exhibition delivers an impression of isolation, and most of their attempts end in fatal error. Eruptions and slumps. Enormous, academician pictures of Soviet history with the victorious military staff and way-larger-than-life figures … If we are looking for a booming tendency, the Russians do not seem to be able to provide it’).

At the end of his article, Vaszary addressed the Hungarian exhibition (of works by him and his students), establishing that it is:

undoubtedly harmonious, since only the newest tendencies are represented, and thus it most thoroughly fulfils the Italian call. Compared to the Western nations in terms of its progressivity, we can firmly establish that its progress is unified, it is fresh and direct and, above all, colourful. The Hungarian Pavilion is easy to overview since it focused on bringing together a varied material, the pieces of which nevertheless belong together. Not every pavilion succeeded in realising this intention.[28]

It is clear from Vaszary’s report that he sought ‘the progressive’ everywhere, viewing an exhibition positively wherever he found it.

This first Biennale under Antonio Maraini was not a success, attracting a record low number of visitors (172,841). Maraini and Mussolini made every effort to remove the Biennale away from regional Venetian city control, and achieved this by 1930.[29] Since it was now a state responsibility, it is no surprise that ‘in a totalitarian state, it became a representative affair of the state rather than an art event’, as Anna Bálványos has shown.[30] Mussolini wanted to expand the Biennale into a world-leading cultural and political event, continually adding new genres, and intending to attract the attention of every political and diplomatic leader whom he regarded as important and to whom the new Italy was to demonstrate its greatness.[31] Following an ostensibly-administrative reorganisation in 1930, political interference in the exhibition grew stronger. The official invitation for the 1930 Biennale requested Italian-inspired works from participants. The show was then sharply criticised in the international press for its pre-set theme, which most participants thought was guided by something other than artistic principles. Most national exhibitions could not (or did not want to) conform to the stipulations; exhibits thus became ‘inconsistent and uneven’.[32] It was only the Hungarian Pavilion that fully complied with the programme. A key figure here was Tibor Gerevich, an outstanding art historian, internationally renowned scholar of the Italian Renaissance and ambitious cultural organiser. He was director of the Hungarian Historical Institute in Rome from 1924, the first head of the ‘Collegium Hungaricum’[33] and the Rome scholarship established by Klebelsberg in 1928, and the conceptual architect and international advocate of the circle which became known as the ‘School of Rome’.[34] Due in part to his excellent contacts in Italy and strong negotiating skills, Gerevich was granted a decisive role in selecting Hungarian materials for the 1930 Biennale. He viewed the request for ‘Italian-inspired art’ as a favourable opportunity to present Hungarian fellows currently affiliated with the Rome institution.[35] The leader of the School of Rome was Vilmos Aba-Novák, whose work also dominated commissions for murals in public buildings during the interwar period. One can trace the gradual unfolding of Aba-Novák’s artistic and Gerevich’s theoretical repertoire in their Biennale involvement between 1930 and 1942, progressing together from attempts to rejuvenate artistic form to aspirations of directly representing the state.[36] The increasingly strained political atmosphere in Hungary from 1938 onwards, the introduction of anti-Jewish laws and the emergence of the extreme right, as well as Hungary’s ever closer relations with Germany impacted little on Hungarian participation in Venice.[37] This was mostly due to Gerevich’s determined anti-German stance. A number of progressive artists who had been most vilified by the extreme right were exhibited in Venice in 1940 and even in 1942, even if in significantly smaller numbers than ‘the Romans’.

In these two years, ever fewer countries engaged in the Biennale; participation reached its lowest historical point in 1942, when only ten countries (Bulgaria, Denmark, Croatia, Hungary, Germany, Romania, Spain, and Slovakia, and two neutral states, Switzerland and Sweden) took part.[38] The Biennale organisers ‘filled’ the empty pavilions with Italian military art: separate pavilions were dedicated to works depicting the strength of the army, air forces and navy. In the middle of the war, the Biennale became a curious assortment of militant and pro-peace art.

Organisation of the next Biennale continued right up until the first bombings of Porto Marghera and Mestre in May 1944. This was followed by an official cancellation of the event, and in 1944 and 1946, no Venice Biennale took place at the Giardini Pubblici. When the Allies attacked Venice and its environs, the historical part of the city was left entirely intact, including the Giardini, the centre of the Biennale. This meant that, by and large, the Biennale could continue anew, almost without interruption or major reconstruction, after the Second World War. This was of course also facilitated by the Biennale’ steadfast structure. As Jan Andreas May put it: ‘Any ideology was able to use this stage and preserve, together with participating marionette states, the appearance of its public character, indeed its internationalism’.[39] For post-Fascist Italy, the 1948 Biennale was of exceptional political and cultural importance, as the pre-eminent British art historian Douglas Cooper summarised it in The Burlington Magazine: this was the first truly large-scale event in Italy since the end of the Second World War, at which Europe’s leading politicians could assemble together with the most prominent contemporary theorists, art historians, and artists.[40]

The twenty-fourth Venice Biennale opened its doors in 1948 with Giovanni Ponti as its new president, and Rodolfo Pallucchini, a well-travelled expert on the Venetian Renaissance and modern art, one of the greatest art historians of the twentieth century, as its general secretary. Preparations began in 1947, initially within the pre-war structure. The main aim was to secure the highest possible number of participants. Since most countries were struggling with social and economic problems after the war, many pavilions either remained empty in 1948, or were furnished by the Italians with various temporary exhibitions: the Yugoslav Pavilion housed a retrospective show of Oskar Kokoschka’s works, and a large selection from Peggy Guggenheim’s private American collection was shown in the Greek Pavilion, which turned out to be the greatest sensation of that year.

After 1948, addressing the Biennale’s future, its long-term transformation, structural modernisation, and the conceptualisation of its new artistic profile became due. The new geopolitical alignment brought about by the Iron Curtain confronted the Biennale as an institution with a string of new situations and challenges, in terms of national pavilions and national participation.

Three painters and one sculptor: József Egry, Ödön Márffy, István Szőnyi, and Béni Ferenczy (1948)

After the Second World War, Hungary belonged to the Soviet-occupied zone. For the three years between 1945 and 1948, it remained undecided whether the country would seize the post-war historical turn and restart as a democratic state or turn into a Soviet-style one-party dictatorship. After the democratic elections of 1945, the Hungarian Communist Party rapidly demolished the multi-party system and gradually eliminated its middle-class opposition. By 1948–49, a total Communist dictatorship was in place under Mátyás Rákosi, who remained in power until the outbreak of the 1956 revolution.

Despite the material difficulties, the cultural administration of the provisionally-coalition-based state did everything to secure participation at the first post-war Biennale. Much like it had done after losing the First World War, the country attempted to use art to improve and augment its image abroad. After many years of disuse, the Hungarian Pavilion had fallen into such poor condition that the standard annual maintenance was not enough to restore it for exhibition purposes. Since the cultural budget had no separate funds for reconstruction and renovation, Hungary used the Romanian pavilion for the 1948 exhibition, as Romania stayed away that year.

That year’s Hungarian exhibition took an explicitly-art-historical approach. Almost every show that year featured a retrospective ‘rehabilitation’ of fin-de-siècle modernism, and the modern and avant-garde tendencies of the interwar years and early 1940s.[41] Among others, the Central Pavilion featured the masters of French Impressionism, a retrospective of Paul Klee, as well as larger, comprehensive exhibitions which included Pablo Picasso’s works or artists who had been banned for their ‘degenerate art’ in Nazi Germany. Even prior to the founding of the state of Israel, Israeli artists were exhibited in the Venice Pavilion for the first time. The French Pavilion showed works by Marc Chagall and Georges Braque, the Austrian Pavilion exhibited Fritz Wotrube and Egon Schiele, while the British Pavilion featured works by Henry Moore and William Turner. The 1948 Biennale attracted over two hundred thousand visitors, representing a great success for Italy after the low numbers in 1940 and 1942, and its popularity was largely due to the European avant-garde’s entry to Venice.[42]

Since the various official structures of the pre-war art world and international exhibition planning had fallen apart, the 1948 Hungarian Pavilion was realised as the effort of new participants. Gerevich was not reappointed to an organisational role in the new system. He had lost his decisive official role in shaping art policy, and it was clear that the new culture department would seek a replacement Biennale commissioner. Gerevich had also been forced to leave the Collegium Hungaricum in Rome before it completely ceased operations in the 1950s. After 1945, he only retained his university professorship in Budapest, a post he held until his death in 1954. His earlier anti-German sentiment somewhat exonerated him after the war.[43]

Just as the School of Rome stopped functioning after the war, the pro-modern Képzőművészet Új Társasága (New Society of Artists) also ceased its activities. Nor was any attempt made to relaunch the conservative Képzőművészeti Társulat (Fine Arts Association). Meanwhile, it was out of the question for international exhibitions of Hungarian art to include works by young artists from the new emerging groups, in particular the Európai Iskola (European School), formed with great anticipation in 1945 to emulate modern European tendencies and become their Hungarian parallel, or the group that splintered from them in 1946, the Elvont Művészek Csoportja (Group of Abstract Artists).[44] The 1948 Biennale in fact took place in something of a vacuum without any distinct exhibition concept. It is therefore no surprise that most works shown in Venice originated from museum or private collections.

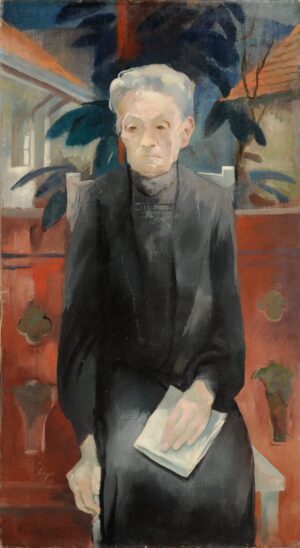

In 1946, the Hungarian state liquidated its consulates in Venice, Trieste, and Fiume (now Rijeka). Gyula Ortutay, the new minister for religion and public education, appointed the linguist and Italy expert Pál Ruzicska to oversee the selection of Hungarian works for the 1948 Biennale; Ruzicska had left Hungary in 1945 before the Soviet occupation and settled in Milan, where he was appointed as director of the Hungarian Institute. The result of Ruzicska’s appointment was three quasi-solo exhibitions clearly intended as retrospective shows.[45] Three painters from the older generation were selected in acknowledgement of their respective bodies of work: József Egry (aged sixty-five), Ödön Márffy (seventy), and István Szőnyi (fifty-four) (Fig. 17.4). Moreover, all exhibited artists had recently been awarded various official state prizes.

The 1948 Hungarian exhibition in Venice virtually echoed the 1934 show, which also included all three artists. Based on the list of these and other participants, it is fair to assume that the main aim was to grant, as a form of ‘compensation’, exhibition opportunity at a large international event to those who had been excluded from, or marginalised in, other surveys of the 1930s, and particularly those in 1940 and 1942. If that year’s selection had a cultural, political, or representational ambition at all, it was to demonstrate in the international arena that Hungary was now a different country, one that guaranteed a prominent place to artists at whom the ‘previous’ Hungary balked. National-conservative idioms were explicitly avoided, as were political, historical, or biblically themed pictures; instead, the halls were filled with ‘neutral’ landscapes, still lifes, portraits, and nudes. After the politicised show of 1942, Hungary now exhibited humanistic conversation pieces, and instead of political content and historical references, the focus was on pure pictorial issues.

Interwar paintings by Egry, Márffy, and Szőnyi were given individual halls, where sculptures and medallions by Béni Ferenczy were interspersed through the room.[46] Essentially, this was a ‘best of’ selection of works by the Képzőművészet Új Társasága and members of the ‘Gresham circle’, a band of oppositional artists and intellectuals who had regularly met at the Gresham coffee house in the 1920s. After 1945, the interwar ‘Gresham’ artists were appointed to leading roles, including teaching posts at the Hungarian Academy of Fine Arts and other significant positions in the arts. Szőnyi, for example, was nominated as president of the newly formed Hungarian Arts Council. At the same time, Aba-Novák’s frescoes in public buildings were overpainted after 1945, and he himself was dubbed, until the 1960s, the negative embodiment of the Horthy-era ‘regime painter’, while his former colleagues at the School of Rome ‘adapted seamlessly to the new system’s thematic and aesthetic principles’, and went on securing opportunities to exhibit their works.[47]

The international press was broadly intrigued by the first post-war Venice Biennale, and this interest also extended to the Hungarian Pavilion. A critic in Das Kunstwerk described the exhibitions of smaller countries (specifically Belgium, Holland, Hungary, and the geographically-larger but geopolitically-‘redrawn’ Poland) as surprisingly superior, emphasising that they stood their ground not only in comparison to their earlier selves, but also according to international standards.[48] Max Eichenberger, the editor of the Swiss Du Kulturelle Monatsschrift, highlighted the Hungarian and Polish use of an international formal language that came to replace their earlier emphasis on national character.[49] He declared that Ferenczy had transferred August Rodin and Antoine Bourdelle’s sculptures from Paris to Budapest with considerable success, assimilating local specificity into his art and thus creating a unique formal world. Precisely the same ‘successful transplant’ also characterised Márffy’s Paris-Budapest and Szőnyi’s Rome-Budapest connections, both of which Eichenberger regarded as representing a harmonious combination of post-Impressionism and ‘pre-Expressionism’. Although this statement was correct insofar as both had studied in these Western-European cities and were undoubtedly inspired by what they had seen and experienced there, it is nonetheless simplistic to speak of a mere ‘transplantation’ of Western elements. Márffy, Egry, and Szőnyi’s pictures not only moved beyond post-Impressionist landscape depiction and figuration towards geometric abstraction, but also surpassed the material in favour of individual spirituality. Their canvases addressed serious social problems as well: poverty, loneliness, the emptied-out individual and his disappointment in society. One constant factor in curating national pavilions is the need to connect to the country of origin and its contemporary problems; naturally this was accomplished somewhat differently in the post-war years than in today’s globalised world.

How then were the Hungarian materials compiled to create a whole in 1948? The show can perhaps be best understood as an exploration of the relations between man and nature. Spectral waterside landscapes by the ‘cosmic, transcendent’ Egry, and Szőnyi’s ‘intimate, humanistic’ landscapes of the Zebegény region and genre paintings of peasant life were accompanied by Márffi’s lakeside landscapes, still lifes, and portraits.[50] Despite the subject-matter, the works transcended faithfulness to nature or the recording of mere impressions. Just like the self-portraits of his inner struggle, Egry’s landscapes are full of tension, drama, and vibrant colours, while Szőnyi’s pictures radiate the bleakness of rural life, and Márffy’s earlier decorative, colouristic style was replaced by a ‘denser, more fixed, more rational’ formal language.[51] Alongside the nature pictures, Béni Ferenczy’s expressive figurines (mostly his nudes)—closed, solid yet dynamic in form—imparted man’s true, plastic presence in the Hungarian Pavilion.

As a consequence of Hungary’s Soviet-style Communist turn and the establishment of a one-party system in 1948–49, many hopes for freedom and democracy were completely dashed by 1949.[52] After the 1948 show, Hungary’s participation witnessed its greatest turn: in accordance with Soviet policy and under Soviet occupation, Hungary did not join the event between 1950 and 1956.[53] However, the country’s absence did not bring about a total lack of discourse on the subject. On the contrary: with an intensity never seen before, discussions were conducted over the ‘correctness’ of partaking, and whether to retain or discard the Hungarian Pavilion.

From the enormous number of written documents that have survived, it becomes clear that the directors of the Venice Biennale took every opportunity to formally invite Hungary during its period of abstention, and instructed the country to maintain the upkeep of its Pavilion building.[54] From 1949 on, official discussions on the ‘Biennale matter’ involved three participants: the Foreign Office, the Institute of Cultural Relations (Kulturális Kapcsolatok Intézete, formed in 1949), and the Ministry of Public Education. Debates revolved around two fundamental questions: (1) what should happen to the Pavilion building (whether it should be restored to its original condition; whether the existing building should be rebuilt with Italian or Hungarian architects; whether it should be knocked down and replaced with a new building at a new location; or whether it should be ‘handed over’ to another nation); and (2) whether Hungary should contribute to future Venice Biennales. The Italian directors clearly prioritised swift repairs, since the sight of a partly ruined building was detrimental to the image of the Biennale itself. The Italians made direct contact with the Foreign Office and the Institute of Cultural Relations via the Hungarian Embassy in Rome, urging the Pavilion’s rapid restoration and Hungary’s continued cooperation. However, the Ministry of Public Education was directly responsible for the building’s maintenance, and there was no clear position or decision taken on the Biennale until 1956. At times, the decision followed the non-participation policy of the Soviets and the other ‘fraternal’ countries’. At others, preparations were cancelled by decree from ‘the highest levels’ and without justification one month before the opening, even though the General Department of Fine Arts (Képzőművészeti Főosztály) had supported taking part (as was the case in 1952 and 1954), and a list of recommended artists had already been compiled, with specific works named.[55] The documents also illustrate other cases, when Hungary first confirmed its participation in writing to the Biennale directors (19 February 1952), but then withdrew one month later (22 March 1952), citing ‘technical reasons’.[56] This long series of delays and ‘prevarications’ lasted until February 1956, until a change of heart from Mrs. Ernő Berda, then head of the General Department of Fine Arts. She had otherwise said on a number of occasions that ‘for my part, I see no reason to concern ourselves with [the Hungarian Pavilion] building’, yet this time she announced in favour of participation.[57] She justified her decision with the following:

Progressive artists in capitalist countries who seek realism [and not abstraction] would benefit from acquainting themselves with our best works. It should be noted that the reactionary cultural policy of the former system recognised the importance of regular participation in international exhibitions. Our prolonged absence might currently invite cultural political attacks both from our artists and the capitalist countries.[58]

This ‘reasoning’, and not least the Soviets’ return to Venice in 1956, proved influential. Thereafter, the pace of change accelerated concerning both the fate of the building and (renewed) participation at the Biennale.

Translated by Gwen Jones

Citations

[1] This text is a reworked version of two chapters of my doctoral thesis: Kinga Bódi, ‘Hungarian Participation at the Venice Fine Arts Biennale 1895-1948’ (PhD thesis, ELTE University, 2014), accessed 30 October 2019, https://edit.elte.hu/xmlui/handle/10831/30842

[2] The Austro-Hungarian Empire (or Austria-Hungary), established in 1867, produced a dualist state confederation that was politically, economically, socially, ethnically, and culturally exceptionally complex. By the second half of the nineteenth century, the great European nation-states had already been formed, while the Austro-Hungarian monarchy still represented a multi-ethnic political formation in the region. In legal terms, the dualist system was a constitutional monarchy. Its two halves, the Austrian Empire and the Hungarian Kingdom, were connected by a shared ruler, and common foreign policy, military, and financial affairs. The Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867 undoubtedly increased the monarchy’s international political and economic weight within Europe while, at the same time, it did not grant Hungary full independence. The monarchy (and within it Hungary) had to handle and solve an increasing number of political, economic, and social problems towards the end of the nineteenth century, such as relaxation of the rigid social order and hierarchy, fresh government crises, and intensifying demands from national minorities. All the while the Hungarian government continued to regard culture as a crucial fertile soil to nurture a positive national image. The Austro-Hungarian monarchy finally came to an end with its defeat in the First World War in 1918. The 1920 Peace Treaty of Trianon redrew Hungary’s borders and heralded the monarchy’s final disintegration.

[3] The successive forms of state were: the Austro-Hungarian monarchy (1867–1918); the First Hungarian Republic (1918–1919); Republic of Councils (1919); the Hungarian Kingdom, a constitutional monarchy under governor Miklós Horthy (1919–1945); the Hungarian Republic (1945–1948); and the Hungarian People’s Republic, a Soviet-style one-party system under Mátyás Rákosi (1949–1956).

[4] Máriusz Rabinovszky, ‘Művészeti életünk pangásáról’, Nyugat 19/11 (1926): pp. 1023–24.

[5] On the role of Biennale Commissar János Vaszary see Emese Révész’s outstanding publication on his years at the Academy of Fine Arts, and Katinka Borsányi’s text on the 1928 Italian press coverage of the Hungarian show: Emese Révész, ‘Csók István és Vaszary János a Képzőművészeti Főiskolán 1920–1932’, in Szilvia Köves (ed.), Reform, alternatív és progresszív műhelyiskolák 1896–1944 (Budapest: Magyar Iparművészeti Egyetem, 2003), pp. 11–26; Katinka Borsányi, ‘L’arte ungerese nella stampa italiana alla Biennale di Venezia, 1928–1930’, Rivista di Studi Ungheresi 8 (2009): pp. 141–153.

[6] Máriusz Rabinovszky, ‘A művészeti pályázatok problémájáról’ Nyugat 21 (1928): pp. 631–633.

[7] Rabinovszky, ‘A művészeti pályázatok problémájáról’, p. 633.

[8] Rabinovszky, ‘A művészeti pályázatok problémájáról’, p. 633.

[9] Emese Révész, ‘“Modern művészetet – az ifjúságért!” Vaszary János művészetpedagógiája’, in Mariann Gergely and Edit Plesznivy (eds.), Vaszary János (Budapest: Magyar Nemzeti Galéria, 2007), p. 126.

[10] For more detail on the Italian press coverage in daily papers, see: Borsányi, ‘L’arte ungerese’.

[11] Ugo Nebbia, La XVI Esposizione Internazionale d’Arte Venezia (Milan and Rome: Alfieri, 1928), pp. 98–103.

[12] International critiques later echoed this sort of explanation of the lively, intense, and animated colours in modern Hungarian painting with reference to ardent ‘Hungarian blood and race’. In the introduction to the catalogue for the 1931 exhibition Modern Hungarian Paintings at the Silberman Galleries in New York, these exact same attributes and phrases are used to describe the art of Vaszary, Berény, Márffy, Czóbel, and Aba-Novák. See: Malcom Vaughan, ‘Modern Hungarian Paintings’, Parnassus 8/3 (1931): p. 9. The exhibition was open from 1 to 19 December 1931.

[13] Nebbia, La XVI Esposizione, p. 99.

[14] Oszkár Márffy, ‘A nemzetközi képzőművészeti kiállítás Velencében’, Képzőművészet 2/12 (1928): p. 178.

[15] Nándor Gyöngyösi, ‘A külföldi kiállítások ügye 1928-ban. Nyílt levél Kertész K. Róbert államtitkár úrhoz, mint a Képzőművészeti Tanács elnökéhez’, Képzőművészet 2/12 (1928): pp. 145–148.

[16] Nándor Gyöngyösi, ‘A külföldi kiállítások ügye’, Képzőművészet 2/10 (1928): pp. 115–118.

[17] Imre Knopp, ‘Az Országos Képzőművészeti Tanács Külföldi Kiállításokat rendező Bizottságának reformja’, Képzőművészet 2/15 (1928): p. 239.

[18] Knopp, ‘Az Országos Képzőművészeti’, p. 239.

[19] Béla Iványi-Grünwald, ‘A magyar művészet huszonnegyedik órájában’, Pesti Napló (11 November 1928): p. 33. Zoltán Farkas also expressed his faith in youth and objected to their exclusion from international exhibitions. See: Zoltán Farkas, ‘Visszafelé megyünk’, Nyugat 22/15 (1929): pp. 180–185.

[20] Anonymous, ‘Fordulat a külföldi kiállítások ügyében. A Kultuszminisztérium letiltotta a növendékeket és a szélsőségeseket a külföldi kiállításokból’, Képzőművészet 3/22 (1929): pp. 155–160. Reprinted in Révész, ‘Csók István és Vaszary János’, p. 13.

[21] Emese Révész, ‘Az iskola és a nyilvánosság’, in Katalin Blaskóné Majkó and Annamária Szőke (eds.), A Mintarajztanodától a Képzőművészeti Főiskoláig (Budapest: Magyar Képzőművészeti Egyetem, 2002), p. 136.

[22] Ursula Zeller (ed.), Die deutschen Beiträge zur Biennale Venedig 1895–2007 (Stuttgart and Köln: Institut für Auslandsbeziehungen and Dumont, 2007), p. 194.

[23] Among the Dutch artists exhibited were Alfred Wiegmann, Jan Sluijters, Willem van Konynenburg, and Lodewijk Schelfhout. See: L. Brosch, ‘Die XVI. Biennale in Venedig’, Der Cicerone 20/18 (1928): p. 601.

[24] Raffaele Calzini, ‘The Sixteenth International Exhibition of Modern Art at Venice II. The Non-Italian Sections’, The Studio 96 (1928): p. 127.

[25] Today, Italy has no separate national pavilion in the Giardini, only a smaller, thematic exhibition in a separate space at the Arsenale.

[26] Between 1926 and 1942, Antonio Maraini was the secretary general of the Venice Biennale. He enjoyed the full trust of Benito Mussolini throughout and, by 1930, had in effect annexed the Biennale to Italian Fascist politics. As Jan Andreas May has shown, Mussolini’s support for Futurist art (founded in 1909) between the wars was grounded in nostalgia, however, he was never able to elevate it to the level of official state art. Instead, it was the more populist Novocento, with its classicising orientation, that succeeded in addressing the broader masses. See: Jan Andreas May, La Biennale di Venezia. Kontinuität und Wandel in der venezianischen Ausstellungspolitik 1895–1948 (Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 2009), p. 111.

[27] János Vaszary, ‘A veneziai kiállítás’, Pesti Napló (13 May 1928): p. 37.

[28] Vaszary, ‘A veneziai kiállítás’, p. 37.

[29] May, La Biennale di Venezia, p. 125.

[30] Anna Bálványos, ‘Magyar részvétel a Velencei Biennálén 1895–1948’, in Péter Sinkovits (ed.), Magyar művészet a Velencei Biennálén (Budapest: Új Művészet Alapítvány, 1993), p. 47.

[31] The first Venice Music Festival (Festival Internazionale di Musica Contemporanea) was in 1930, the first Venice Film Festival (Mostra Internazionale d’Arte Cinematografica) was in 1932, and the first Venice Theatre Festival (Festival del Teatro della Biennale) was held in 1934.

[32] ‘Tárlatok. A Velencei Nemzetközi Kiállítás’, Képzőművészet 4/32 (1930): p. 165.

[33] Klebelsberg placed great emphasis on the development of Hungarian cultural and academic international relations, and following the opening of a Collegium Hungaricum in Berlin and Vienna, a Hungarian academy was also established in Rome in 1928 on the Palazzo Falconieri. The building was purchased in 1927 and housed the Hungarian Historical Institute before its remit expanded to include the Collegium Hungaricum. There were already plans under way to open a similar institute in Paris. All this appeared pioneering at the time, with even the London-based The Studio reporting on the opening of a Hungarian institute in Rome. See: A.E., ‘Budapest’, The Studio 96 (1928): pp. 146–49.

[34] The term ‘School of Rome’ originates from Gerevich, and later entered accepted use in the specialist literature. In 1928, Gerevich circumvented the standard application process and invited Vilmos Aba-Novák, Károly Patkó, and István Szőnyi to work in Rome. The literature uses this date as the starting point of the School’s history. (See also Julianna Szücs’s essay in this volume – The Editor)

[35] Csilla Markója, ‘Gerevich Tibor és a velencei biennálék – katalógusbevezetők 1930 és 1942 között’, Enigma 16/59 (2009): pp. 79–107.

[36] Gerevich’s preferred formal characteristics after the Italian model were: ‘simplified lines, calm surfaces, large-scale forms, decorative impacts’. See: László Százados, A két világháború közötti művészetpolitika és tudományosság kérdése Gerevich Tibor munkásságának tükrében (MA thesis, ELTE BTK Art History Department, 1989), pp. 40–41.

[37] For an English-language summary of Hungary’s interwar political situation, see: Thomas L. Sakmyster, Hungary’s Admiral on Horseback: Miklós Horthy, 1918-1944 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1994).

[38] In this new geopolitical situation, the former Czechoslovak pavilion was used to exhibit artists from independent Slovakia.

[39] May, La Biennale di Venezia, p. 216.

[40] Douglas Cooper, ‘24th Biennial Exhibition, Venice’, The Burlington Magazine 90/547 (1948): p. 290.

[41] Peter Joch, ‘Die Ära der Retrospektiven 1948–1962. Wiedergutmachnung, Rekonstruktion und Archäologie des Progressiven’, in Zeller (ed.), Die deutschen Beiträge, pp. 89–106.

[42] Enzo Di Martino, The History of the Venice Biennale 1895–2005. Visual Arts, Architecture, Cinema, Dance, Music, Theatre (Venice and Turin: Papiro Arte, 2005), p. 118.

[43] Csilla Markója, ‘Gerevich Tibor görbe tükrökben’, Enigma 16/60 (2009): p. 9.

[44] On the European School, see the essays by Gábor Pataki and Péter György in this volume. (The Editor)

[45] ‘Padiglione dell’Ungheria’, in XXIV. Biennale di Venezia, exhibition catalogue (Venice: Serenissima, 1948), pp. 321–7.

[46] Because of Ferenczy’s cultural role during the Republic of Councils, he was forced into exile for two years after 1919. He was only appointed as a teacher at the Hungarian Academy of Fine Arts a long time after his return, in 1945.

[47] Péter Molnos, ‘Újrafestve. Gerevich Tibor és Aba-Novák Vilmos’, Enigma 16/59 (2009): p. 34.

[48] Max Peiffer-Watenphul, ‘Biennale di Venezia’, Das Kunstwerk 2/3–4 (1948): pp. 35–41.

[49] Max Eichenberger, ‘Panorama der modernen Malerei und Plastik im Spiegel der Biennale Venedig 1948’, Du: Kulturelle Monatsschrift 8/11 (1948): p. 17.

[50] Máriusz Rabinovszky, ‘Szőnyi’, Nyugat 22/3 (1929): p. 215.

[51] Zoltán Rockenbauer, Márffy Ödön. Monográfia és életmű-katalógus (PhD thesis, ELTE BTK Art History Doctoral School, 2008), p. 166.

[52] For an English-language summary of contemporary Hungarian macropolitics, see: Tibor Valuch and György Gyarmati, Hungary under Soviet Domination 1944–1989 (New York: Columbia University Press, 2010).

[53] After an absence of 22 years, the Soviet Union returned to Venice in 1956. Nikolai Molok (ed.), Russian Artists at the Venice Biennale 1895–2013 (Moscow: Stella Art Foundation, 2013), p. 352.

[54] The relevant documents on this subject are to be found among the Hungarian National Archives’ (MNL MOL) post-1945 holdings on the Foreign Ministry (XIX-J-1), the Institute of Cultural Relations (XIX-A-33), a Ministry of Public Education (XIX-I-3), the Ministry of Culture (XIX-I-4) and the Kunsthalle (XXVI-I-10).

[55] ‘We hereby announce that the Political Committee does not consent to our participation in the “Biennale” fine arts exhibition in Venice in 1954’. Zoltán Komáromi (Central Leadership of the Hungarian Workers’ Party), letter to Ferenc Jánosi (Ministry of Public Education). Budapest (11 May 1954). MNL MOL XIX-I-3-l (Ministry of Public Education ‘TÜK’ [Top Secret] documents 1950–1957) 072/7/1954.

[56] Iván Kálló, letters to Giovanni Ponti, Budapest (19 February and 22 March 1952). ASAC, Venice ‘Scatole Nere. Padiglioni’ Box No. 30 (1952).

[57] Note for László Erdei, Budapest (1 December 1952). MNL MOL XIX-I-3-l (Ministry of Public Education ‘TÜK’ documents 1950–1957) 038/3/1952.

[58] Note on the Venice Biennale exhibition, Budapest (2 February 1956). MNL MOL XIX-I-3-l (Ministry of Public Education ‘TÜK’ documents 1950–1957) 072/3/1954.