#MaterialWitness reconvened for 2019s third session at the Tate Archive in the basement of Tate Britain. Secluded from thronging exhibitions, a door opens onto the world’s foremost collection of documentation on post-1900 British art. This hoard includes more than 900 artists’ personal archives, 100,000 documentary photographs, 3,500 audio-visual recordings and 2,500 artist-designed posters, among other treasures – all kept pristine and accessible by expert archivists.

We were here to learn about Tate’s holdings in the field of conceptual art, a genre that began to flourish in the late 1960s, and which practitioner Sol LeWitt defined as art where “the idea or concept is the most important aspect of the work.” Our visit began with a tour from archivist Victoria Jenkins. She led us through stores usually off-limits to visitors, sharing her experience of maintaining and cataloguing this unrivalled collection. She also pointed out structural measures for protecting the archive. For example, the stores are accessed through submarine doors. These guard the archive, which sits below the water table, against floods from the nearby Thames. Victoria spoke about challenges of archiving immaterial artworks such as performances, which are abundant in conceptual art.

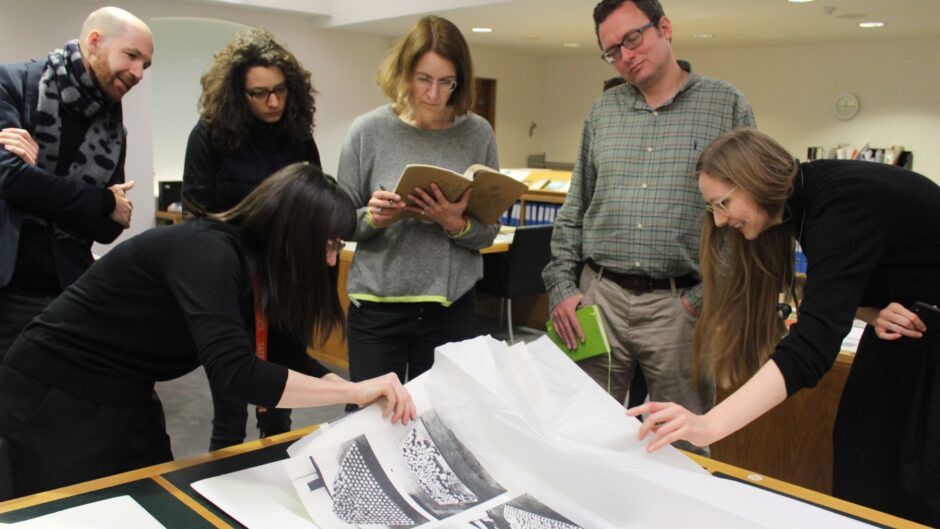

In the reading room, Victoria had set out a range of conceptual art resources for us. Here The Courtauld Institute of Art’s Dr Christian Berger gave a talk exploring other questions posed by conceptual art. Christian was interested in conceptual art’s overlaps with other forms. Perusing Victoria’s materials, these intersections became apparent. If Vito Acconti steps up and down on a stool as many times as he can manage, is that dance? If the Art & Language collective print narrative texts, is this literature? Even the artwork’s identity becomes nebulous. Many conceptual artists write down instructions for enacting ideas. Is an instruction preliminary to the artwork, is it the artwork itself, or does it record a concept that constitutes the real artwork?

Browsing Victoria’s material, I was struck by the catalogue for 557,087, a 1969 exhibition curated by Lucy R. Lippard in Seattle. Lippard sent blank postcards to participating artists, who recorded instructions upon the cards before sending it back. Lippard executed the instructions to create exhibits. The instructions were replicated as a card deck for sale as the catalogue. Since the instructions are arguably artworks in themselves, purchasers acquired not documentation of the show, but the exhibition itself. Readers could shuffle the cards into different sequences, becoming curators of their personal exhibitions.

Lippard’s catalogue made me consider how conceptual instructions themselves could respond to archival challenges that Victoria had described. The result is tatements, a 23-card deck of proposals for actions to be executed in or using the Tate Archive. A PDF can be downloaded through the link below, ready for printing on A6 postcards. The instructions are mischievous; this should not be taken as critique of the Tate’s archivists’ brilliant work, but rather as a celebration of how diligently and thoughtfully they negotiate the quandaries of documenting conceptual art.