Spontaneous exchanges around a manuscript with my peers, experiencing the historical past in person… With a difficult Covid-impacted academic year ending, it was an absolute joy to attend the first in-person Material Witness workshop of 2020-21.

On Friday 25th June, a dozen lucky CHASE students met to consider Canterbury Cathedral in the time of Thomas Becket under the guidance of Dr Emily Guerry, University of Kent. We were also privileged to view elements of an upcoming exhibition at Canterbury Cathedral, led by Sarah Turner, Collections Manager at Canterbury Cathedral and Ariane Langreder, Conservator at the Cathedral Archives and Library. I think it is safe to say that this Material Witness session was cathartic for many of us!

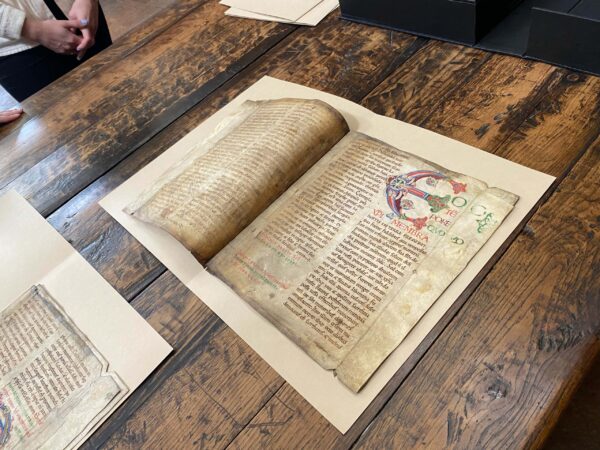

After dividing into smaller groups, my team headed to the Canterbury Cathedral Archives and Library, led by Conservator Ariane Langreder. She introduced us to one of her recent restoration projects: a Passionale produced in Canterbury in the twelfth century. The Passionale is beautifully decorated, the initials showing intricate patterns. The R-initial particularly jumps to mind, with its assorted range of beasts and men devouring one another. Ariane told us the tale of the Passionale, finally reconstituted from other collections which held separated folios and initials from this devotional manuscript. Although on another scale, this reminded me of two current projects which aim to reconstitute libraries and collections: the Manuscripts from German-Speaking Lands and the Whittington’s Gift: Reconstructing the Lost Common Library of London’s Guildhall projects.

To this day, the notion of recreating medieval spaces (or in our case the material interactions one could have had with the original medieval book) is one that I find fascinating, but one that carries its load of challenges, informed guesswork and working against modern suppositions and imposed narratives on the past.

Ariane explained the meticulous restoration procedures carried out to give this Passionale a brand-new life, but one as close as possible to the original. She explained the impact of past conservation procedures: chapters assembled and bound again in the wrong order, the visible mark of modern interventions on the manuscript’s pages. Her work has shifted the focus of the restoration to allow the material object to tell its own story. It made me realise how important and incredibly skilful the work of conservators is. How many of the manuscripts I have interacted with were restored and how little did I notice the hand of the conservator in their (re)making, which made it possible for me to understand the essence of the medieval object? Although the Passionale now remains unbound, I am finally able to consider its full story; from its original one-codex state and organisation to the many fleeting past lives it lived as book covers, as the many marks left on the edge of its pages show.

The second part of the workshop was led by Sarah Turner, who gave us a private tour of the (soon-to-be-open) exhibition of English church plate. I knew very little about this aspect of the Cathedral’s collection, so it was a brand-new lens through which to understand the religious history of England. I had never considered these objects as being able to tell an interesting story before, but this exhibition truly changed that view.

The display includes liturgical objects used nowadays by the Cathedral: few examples are available as the need to purchase communion cups and plates has become less necessary these days. This was the first of many reflections on how religious practices change over time and the relationships communities developed with those ecclesiastical objects. Of these communities, women were no strangers; among the collection were objects designed by a company run by a woman who took up the business from her late husband, whilst another woman donated her familial silverware to be used by her local parish church, ensuring her legacy among her community.

There are also some fine survivals from the Medieval period. Of course, when discussing the history of the English Church, the impact of the Reformation cannot be ignored and here can be seen in striking changes in practices and styles of piety. The communion cup made its first appearance in Edward VI’s reign; to adopt the communion cup was a strong political and religious stance as England shifted to Protestantism. However, the real treasure of this display in my eyes is a surviving medieval chalice and patten, discovered in the tomb of Archbishop Hubert Walter. Medieval chalices are a rarity – many were lost during the Reformation, some possibly melted into new communion cups. Other objects from Archbishop Walter’s tomb are displayed elsewhere and Sarah Turner explained the decision-making process. It is once again to do with what is the best story to tell, or rather the best story the object can tell. We know very little about the reasons for the presence of objects in the burial; for example, we do not know whether there was a personal link between this chalice and the archbishop, or whether it was a gift upon his death. We can be more certain of the role such an object played in ecclesiastical history, however, and how it can frame the narrative told by the exhibition. Once again, we are met with the curator’s role in defining the material object.

We concluded our day with a tour of the Cathedral led by Dr Emily Guerry, concentrating on aspects of the building which would have been familiar to Thomas Becket. The tour revealed the many past lives of the cathedral and its evolution, notably work done recently by restorers who are trying to keep the Cathedral’s history alive and visible.

Throughout the workshop, questions about our vision of and interactions with the material past kept popping into my mind. What place do we want to give those objects in the stories we tell and how can we highlight the objects’ own histories without imposing our own narratives onto them? Is it a bad thing to let the narrative take over the history of the material object? Does it conflict with our desire to ‘salvage’ the past? We might want to insert as little as possible of our personal bias into the reading that we offer of the material object and let it tell its own story, as shown in the recent restoration of the Passionale. Yet, the public’s understanding of the material object often depends on the context we choose for that object – a point demonstrated by Hubert Walter’s chalice and patten. What is to be the centre of the narrative: our vision or the object?

Many thanks to the team who organised this fascinating Material Witness workshop which left me with plenty of food for thought on our relationship with the material object!