Derek Jarman’s creative acts across multiple media have often invited comparison with those of the visionary artist and poet William Blake. As Gray Watson observes, in an illuminating overview of Jarman’s work and personal vision, his ‘whole approach was very close to Blake’s … Blake’s eccentric, radical, anti-materialist and somewhat apocalyptic vision prefigured Jarman’s own’.1 The aim of the present essay is to show how the visionary dimensions to Jarman’s artistic practice were often shaped by—and sometimes in direct dialogue with—the biblical Book of Revelation. Like Blake, Jarman discovered in this paradigmatic account of end-time a source of inspiration for challenging the political culture of his day. Notably, by revisiting and reworking Christian notions of apocalypse, Jarman sought to contest the repressive sexual climate in British culture that located blame for the AIDS crisis primarily in the gay community.2

More specifically, I draw out resonances between imagery of destroyed and dilapidated cityscapes and landscapes in Jarman’s films, paintings and writings, and the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah in the Book of Genesis, a text that remains thoroughly enmeshed with ideas of apocalypse in Christian thought. This will also provide a lens through which to perceive Jarman’s critical engagements with events in his own lifetime that threatened global catastrophe, notably the AIDS pandemic, nuclear weapons and environmental devastation, all of which have invariably been perceived through an apocalyptic or prophetic prism. The aim of this analysis of biblical writings, insofar as they informed Jarman’s thinking, is to throw into relief the artist’s critique of religiously inspired apocalyptic conventions and his desire to highlight the persistence and damaging effects of this discourse on contemporary culture.

Finally, I touch on the broader historical and aesthetic dimensions to Jarman’s encounters with apocalypse. In modernity, at least until the end of the Cold War, the term ‘apocalypse’ tended to be conflated with ideas of catastrophe and closure, even as contemporary representations in fiction or on screen also focus on the post-apocalyptic (which imagines apocalypse as a more drawn-out process). In its original sense, however, the term also referred to disclosure and revelation. Jarman harnessed the radical political potential of apocalypse as a genre, both to engage with the present, as he experienced it in modern Britain, and to open a window onto a future that resisted the seductive rhetoric of end times. Crucially, the artist’s various engagements with apocalyptic themes perform the work of articulating what it means to survive destruction and to cultivate an existence among the ruins. To pursue this endeavour, as will be demonstrated in conclusion, he also had recourse to literary texts, especially from the Middle Ages, that directed attention to alternative modes of thinking and imagining the end of days.

Let us turn first, then, to the story of Sodom. Genesis 19 tells of how two angels come to Sodom one evening to investigate the city’s sins. The patriarch Lot, seeing the angels at the city gates, offers them lodging in his house. But before the household goes to bed, Sodom’s inhabitants besiege the residence and call on Lot to deliver his guests ‘that we may know them’ (19.5).3 Lot offers his two daughters up as an alternative since, he announces, his overriding concern is for the wellbeing of his angelic visitors. This motif of female sexual exchange is often seriously underplayed by commentators obsessed with the implications of the episode for comprehending homosexuality. Threatened with violence, however, Lot and his family are escorted out of the city by the angels; and subsequently, readers are informed, the Lord ‘rained on Sodom and Gomorrah brimstone and fire from the Lord out of heaven; and he overthrew those cities, and all the valley, and all the inhabitants of the cities, and what grew on the ground’ (19.24–25). Then, in the dramatic climax to the tale, Lot’s wife, ignoring the angels’ warning to ‘not look back’ (19.17), is turned into a pillar of salt (19.26).

The destruction of Sodom was traditionally construed as a punishment for bodily depravity, though some modern commentators argue that the episode is chiefly concerned with lack of hospitality to strangers: the inhabitants of Sodom were simply exercising the right to ‘know’ who Lot’s guests were, motivated by an awareness of the patriarch’s alien status in the city. This particular interpretation was bolstered by the Anglican clergyman Derrick Sherwin Bailey, who in 1955 published a book on homosexuality in western Christianity that paved the way for the 1957 Wolfenden report on legal restrictions against male homosexuality in the United Kingdom, which in its turn led to partial decriminalisation in England and Wales a decade later.4 Bailey’s argument that the Sodom story had not originally been written with homosexual acts or desires in mind, and that it more likely involved a condemnation of the Sodomites’ inhospitality to angels, was subsequently taken up by other historians, notably John Boswell, whose seminal study Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality, published in 1980, cites Bailey’s book as a ‘pioneering’ work that significantly advanced research on Christian attitudes to homosexuality.5 Jarman reportedly owned several copies of Boswell’s study and made frequent use of it in his published writings.6 The extant copy of Boswell’s book at Prospect Cottage, Dungeness, where Jarman lived from 1987 until his death in February 1994, still preserves a series of handwritten markers that its owner used to identify some of the medieval churchmen that the author identified as ‘gay’ (Fig. 1). In the opening pages of Jarman’s 1992 memoir, At Your Own Risk, Jarman cites approvingly Boswell’s thesis—itself derived from Bailey—that the biblical story of Sodom was concerned with lack of hospitality. Reflecting on how he has lived the first twenty-five years of his life ‘as a criminal’ and the next twenty-five as a ‘second-class citizen’, Jarman observes that if the sin of the people of Sodom was inhospitality, ‘the lack of hospitality that we have received in my lifetime reveals a true Sodom in the institutions of my country’.7

The cities of the plain, evocatively described in Genesis 19 as being consumed by fire and brimstone, recur repeatedly as motifs or tropes in other sections of the Bible: the books of Isaiah, Ezekiel, Jude and so forth. Most significant of all is the citation of the Sodom story in the Book of Revelation, which concludes the canonical Christian version of the Bible. There, after the seventh seal of the Lord’s book is opened, fire and hail are described falling to earth—trees and grass burn; men drown; sun, moon and stars go dark—before the beastly Satan, condemned to a bottomless pit after his fall from heaven, is released from his confines to wreak further havoc. The beast subsequently makes war on and kills God’s two witnesses: ‘and their dead bodies will lie in the street of the great city, which is allegorically called Sodom and Egypt, where their Lord also was crucified’ (11.8). What is more, a later passage identifies the same great city as the Whore of Babylon, riding a scarlet beast and reigning over the world: ‘And the kings of the earth, who have committed fornication and were wanton with her, will weep and wail over her when they see the smoke of her burning … and say “Alas! alas! thou great city, thou mighty city, Babylon! In one hour has thy judgment come”’ (18.9–10). The story of Sodom’s annihilation was thus yoked, in the Christian Bible, to John the Divine’s vision of global destruction at the end of time. The great city invoked in these verses, which its original author and many commentators since have also identified as a stand-in for Rome, was conflated allegorically with another city, Sodom, whose own fate prefigured both the burning of Babylon and the fiery torments of the damned in hell following God’s final judgement; the city’s decimation represents a prelude to the descent of the New Jerusalem from heaven in the text’s concluding chapters.

Jarman was an avid reader of Saint John’s Apocalypse and it held a firm grip on his imagination. The Book of Revelation is among the most heavily annotated sections in Jarman’s own copy of the Bible, which remains to this day in his library at Prospect Cottage; I have deliberately been quoting from the 1966 Catholic Edition of the Revised Standard Version of the Bible, an English translation adapted for Catholic use, which was the text Jarman knew and worked with.8 Jarman also owned a copy of an edited volume of essays, Facing Apocalypse, which had been published in early 1987, around the time that his feature film The Last of England, with its celebrated invocations of apocalypse, was released. The starting point for Facing Apocalypse, as expressed in its introduction, was that ‘the nuclear arsenal calls forth ancient images of the end, evoking dreams and nightmares of apocalypse from a variety of cultures’; the book’s wager is that a ‘careful scrutiny’ of apocalyptic imagery ‘may make us more sensitive to nuclear war—and to those psychological projections which threaten to erupt in an irreversibleexplosion of hostility’.9 Jarman too, it seems, sought to understand how imagery of the world’s end potentially laid the psychological groundwork for the planet’s real and future destruction through such phenomena as environmental destruction and nuclear disaster. He chose to face apocalypse by confronting the hidden impulses and anxieties it expressed.

Jarman had been drawn to apocalyptic themes throughout his career as an artist and filmmaker. Earlier iterations included his 1978 feature Jubilee, which has been characterised as oscillating between a seemingly archaic and idealised English Renaissance past, represented by Queen Elizabeth I and her sage John Dee, and a ‘postmodern punk apocalypse’ set in the wasteland of Britain’s present.10 Similarly, the script for an unrealised film project, Neutron, which Jarman commenced in 1979 shortly after the release of Jubilee, was conceived both as a Jungian interpretation of the biblical Apocalypse and as a political commentary on the rise of Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative Party, whose members Jarman had already begun to view as the ‘greedy despoilers’ of Britain’s past.11 The recently developed neutron bomb, a specialised type of nuclear weapon that was popularly believed to destroy human beings while leaving infrastructure intact, was the inspiration for Jarman’s title. While Neutron concludes with a final image of its Christlike protagonist Aeon setting out into the sunshine, dressed as ‘a medieval pilgrim with a palmer’s wide-brimmed hat and a shepherd’s staff’, a sign that past corruption had been eliminated and the slate wiped clean, another explicitly medieval-themed script, Bob-Up-a-Down, which Jarman was also working on at the time, features a plot in which a cycle of violence and destruction similarly concludes with an episode of cleansing and renewal.12

An installation at London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in 1984 brought these interests in apocalypse to a head. To complement a retrospective exhibition of his paintings from the 1960s onwards, Jarman created six new works, known as the GBH series (Fig. 2), which were displayed separately in a dark, contemplative, near-sepulchral space within the galleries. The works were monumental in scale, extending almost three metres in height, and featured images of a map of Britain, painted in acrylic, which was surrounded and partially obscured by swirls of charcoal, gold and fiery red pigment. The paint was applied to a hand-laminated base, comprising a sheet of linen layered to the front with torn newspaper impregnated with glue, creating a densely textured and undulating surface that further obscured the aerial view of Britain.13 The imagery evokes smoke, flames and burning, signalling that viewers are being confronted with a vision of apocalypse, while the circles inscribed over each map call to mind the targeting sights of a wartime bombing mission. Jarman had been struck, when reviewing Britain’s shape in an atlas, by its resemblance to an H-bomb explosion, lending support to this interpretation.14

Smaller-scale works linked to the GBH series similarly resonate with the political contexts that provoked Jarman’s engagement with the idiom of apocalypse. Around two years after exhibiting the GBH series at the ICA, and while planning the film that would become The Last of England, Jarman created a work composed of black impasto, laid thickly over a gilded canvas and imprinted with a cracked pane of glass, that he entitled Grievous Bodily Harm (Fig. 3). The glass, engraved with the words ‘VICTORIAN VALUES’ and ‘Night life’ and the letters ‘GB’, is placed over a sketchy red map of Britain. ‘GB’ of course references Great Britain as well as the painting’s title, while ‘Victorian values’ call to mind Margaret Thatcher’s use of the phrase as a rallying cry in political campaigns from 1983 onwards.15 The ‘Night life’ phrase is more ambiguous but could refer variously to the nightmarish shadow cast by Thatcher’s policies and the Cold War, and to sites of nocturnal possibility and queer connection, such as the cruising grounds of Hampstead Heath, which supposedly threatened to disrupt the nation’s moral compass. Also explicitly dwelling on the menace of nuclear war and climate change is a work in two parts (Fig. 4): a painted panel featuring a shadowy landmass recognisable as Britain, streaked with red and white pigment and painted over a gold ground, and a gilt-framed clockface with its hands forebodingly set at one minute to midnight. The mock timepiece evokes the Doomsday Clock that the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists conceived in 1947 as a metaphor for the risk posed to humanity and the planet by nuclear weapons and climate change. At the time of writing, reflecting the intensification of threats in recent years, the Doomsday Clock is set at 100 seconds to midnight.16 But in the early 1980s, during which Jarman created these works, fear of nuclear annihilation was also very real, as was a heightened awareness of environmental concerns such as acid rain and the depletion of the ozone layer; Jarman’s art and writings from his final decade are likewise peppered with references to ecological devastation.17

The composition and colours of the GBH group and related paintings are also loosely reminiscent of works by William Blake, notably ‘The Ancient of Days’, Blake’s visionary frontispiece to his apocalypse-themed Europe: A Prophecy (1794), which shows the mythical figure Urizen using a compass to impose order on the material world at the moment of creation.18 In addition, the surfaces and cartographic forms of the GBH series have been compared to the Hereford mappa mundi (Fig. 5), a medieval world map comparable in scale to Jarman’s paintings, which is inscribed on a single sheet of parchment and represents the whole of creation—people, animals, places and historical events—as properly ordered and organised within a circle according to Christian principles.19 While it is not clear if Jarman knew the Hereford map or encountered it in person, it is worth noting that it includes stylised depictions of Sodom and Gomorrah (Fig. 6), shown as buildings submerged beneath the Dead Sea, as well as a portrayal of Lot’s wife ‘mutata in petra salis’ [turned into a pillar of salt]. However, by contrast with the mappa mundi’s orderly arrangements of time and space, which were designed to accord with prevailing systems of geographical, religious, historical and legendary knowledge, Jarman’s images evoke only disorder and destruction. As critic John Roberts noted, in a review of the ICA exhibition at the time it opened, the GBH series can be interpreted variously ‘as a visionary projection of Britain under a nuclear fall-out cloud … as a picture of Britain in the grips of the fires of Toxteth, Brixton and Bristol [riots in the early 1980s that occurred against a background of tensions between local police and Black communities], and as a glorious act of expulsion and exorcism: the ritual burning of Little England, this Sceptered Isle’.20

One of the titles for the feature that eventually became The Last of England was GBH, signalling a clear thread of continuity between the themes of Jarman’s 1987 film and the earlier paintings. Moreover, another of the film’s working titles, The Dead Sea, conjures up the ties between the biblical Sodom story and Saint John the Divine’s vision of Apocalypse at the end of time. The collection of diary entries, interviews and notes for the script of The Last of England, published to coincide with the film’s release and later republished under the title Kicking the Pricks, includes a reflection on the significance of the work’s earlier titles. The Dead Sea suggested, to Jarman, the symbolist painter Arnold Böcklin’s Isle of the Dead, with its image of an oarsman carrying a lone passenger and coffin-shaped object, both of which are swathed in white cloth, to a mysterious rocky islet.21 Also in the back of Jarman’s mind were the ‘dead waters’ that ‘lap ominously’ through the stories of Edgar Allan Poe; and the filmmaker may have been thinking, too, of Poe’s Gothic poem ‘The City in the Sea’, which tells of a strange city with ‘time-eaten towers’ and ‘Babylon-like walls’, while ‘Resignedly, beneath the sky / The melancholy waters lie’.22 This imagery parallels the sequences in The Last of England representing water and shorelines, including footage of refugees waiting in London’s bleak and decaying Docklands (Fig. 7), and a particularly resonant concluding segment in which a group of refugees row themselves silently across a dark expanse of water, lit by the light of a flare—one of Jarman’s signature motifs—as they journey into the shadowy unknown (Fig. 8).

In the conversation in Kicking the Pricks in which he announces these connections, Jarman is also reminded of a parallel to William Holman Hunt’s The Scapegoat (Fig. 9), reflecting that the painting’s subject, the creature ritually burdened with the sins of others in the Book of Leviticus, is shown by Hunt tethered on the Dead Sea shoreline.23 Traditionally, it was believed that the Dead Sea stood for the fate of the cities of the plain in Genesis 19, the barren landscape being cursed with the same fate as the legendary cities described being decimated by fire and brimstone in the biblical text. Lot’s wife’s own destiny to be turned into a statue of salt further cemented this connection in view of the Dead Sea’s salty, sulphurous make-up. Moreover, as H. G. Cocks has shown, claims by a French archaeologist, Louis-Félicien de Saulcy, actually to have located the ruined remains of Sodom and Gomorrah as he travelled around the shores of the Dead Sea in 1851, ignited a vigorous Victorian debate about the realities of biblical history and its status too, perhaps, as a prophetic sign of the Apocalypse to come.24 Just a few years before Hunt painted his picture, in other words, the Dead Sea’s uncanny landscape had been identified as actually retaining physical traces of divinely-inspired cataclysm. Significantly, Hunt had read de Saulcy’s account of his journey to the Dead Sea, and when the Pre-Raphaelite artist went there in 1854, to paint The Scapegoat, he chose as his location the foot of a range of hills known as Jebel Usdum (‘Mount Sodom’), which features salt caves and a pillar of rock salt popularly known as Lot’s Wife.25 Hunt portrays the titular goat of his painting in a desolate and inhospitable landscape, which he identifies in an inscription at the base as ‘Oosdoom’, a transliteration of the Arabic name ‘Usdum’ that de Saulcy had cited as ‘undeniable evidence’ that the ruins he claimed to have ‘discovered’ on the shores of the Dead Sea were indeed those of Sodom.26 The beast’s horns are surrounded by a red woollen band, which denotes the sacrificial animal described in Leviticus 16.21–2 (‘The goat shall bear all their iniquities upon him’), while also anticipating, typologically, Christ’s crown of thorns. Displaced within a barren shoreline strewn only with bones, deposits of salt and withered plants, Hunt’s goat stands isolated against a watery backdrop that is literally dead; it is the only living creature in a setting that the painter himself described as ‘beautifully arranged horrible wilderness’.27 ‘God-forsaken’ could aptly be applied to this landscape, though the imagery surely also brings to mind the wilderness of Dungeness, which Jarman had rediscovered just a few months before completing The Last of England and which is popularly characterised as exuding a ‘post-apocalyptic’ look and aura.28

Ultimately, it was another Pre-Raphaelite painting from the 1850s that provided the inspiration for Jarman’s title: Ford Madox Brown’s The Last of England, which depicts emigrants leaving the white cliffs of Dover behind for life in the colonies.29 But the fact that Jarman’s film was originally shadowed by references to the Dead Sea signals that its celebrated invocations of apocalyptic themes and imagery also deserve to be viewed in light of their connections to the Sodom story. Kicking the Pricks, indeed, identifies a further parallel in a passage in which the director reflects on the film’s ultimate message. It is ‘about England’, Jarman muses, ‘a feeling shared with Oliver Cromwell’, before reciting to the interviewer a series of what he calls ‘mad’ verses that purportedly derive from a speech delivered by Cromwell at the dissolution of Parliament in 1654 but are in fact taken from the biblical Book of Isaiah.30 Jarman quotes from Chapter 63 of Isaiah, a judgement-themed text that provided an important source of language and imagery for the Book of Revelation, which centres on the theme of retribution against those seeking the destruction of Israel. After the prophet asks who it is ‘that cometh from Edom’, a city that had been prophesied by Isaiah’s predecessor Jeremiah (49.18) as suffering the same fate as Sodom and Gomorrah, God announces to the prophet that ‘the day of vengeance is in my heart … And I will tread down the people in mine anger, and make them drunk in my fury’ (Isaiah 63.6). Jarman’s interlocutor subsequently asks whether he reads the Bible, to which the artist responds: ‘Frequently. The Song of Solomon. Revelation’. Referring to an infamous remark by the Manchester chief constable, James Anderton, in December 1986, that prostitutes, drug addicts and homosexuals who had AIDS were ‘swirling round in a human cesspit of their own making’, Jarman subsequently jokes that since he himself is ‘obviously in the cesspit’ he has ‘nothing to lose’, unleashing a series of associations between biblical vengeance, contemporary politics and the stigmatisation of marginalised communities that clearly parallels the Sodom narrative.31

Jarman’s citation from Isaiah, along with his passing reference to Hunt’s The Scapegoat and other allusions to divinely ordained punishment, registers the extent to which British political culture was itself underpinned, at the time of the film’s making, by a climate of scapegoating that worked to position gay men specifically in the proverbial cesspit. Section 28 of the 1988 Local Government Act, which banned the promotion of homosexuality in schools, was perhaps the most egregious instance of this phenomenon in Jarman’s lifetime. Although the passing of Section 28 post-dated the release of The Last of England by a year, the groundwork for the legislation had been laid in 1986, when a Private Member’s Bill aimed at preventing local authorities from ‘promoting homosexuality’ was tabled in the House of Lords.32 John Giffard, Earl of Halsbury, making a case on 18 December 1986 for the Bill’s second reading, issued a homophobic tirade that culminated in the accusation that gay men are a ‘reservoir of venereal diseases. . . . Syphilis, gonorrhoea, genital herpes and now AIDS are characteristically infections of homosexuals’.33 Judge and fellow peer Tom Denning, who likewise spoke vehemently in support of the Bill, quoted verses from Genesis describing the destruction of Sodom and even had the audacity to compare the House of Lords to the biblical Lord who condemned Sodom and Gomorrah in the book of Genesis. Insofar as the legislation functioned as a means of curbing the activities of the supposedly ‘loony left’ councils that, in Denning’s words, ‘corrupted’ children through their use of public funds for ‘homosexual purposes’, the peers who championed the Bill were effectively characterised by Denning as a god issuing divinely-ordained punishment.34 Stigmatising gay men specifically—Lord Halsbury distinguishes in his introductory comments between the ‘relatively harmless lesbian’ and the ‘vicious gay’—this debate neatly encapsulates the rot at the heart of government and the British polity that Jarman’s film so powerfully exposes.35

On 22 December 1986, shortly after completing the filming for The Last of England and just days after the House of Lords had witnessed an outpouring of homophobia in connection with the bill that became Section 28, Jarman had tested positive for HIV antibodies.36 Like other gay men living in London in the 1980s, however, he had been contending, in the years leading up to his own diagnosis, with the virus’s impact on his identity as a gay man. The final pages of Kicking the Prickscontain a series of reflections on the effect of living with HIV on the author’s sense of time. In a lengthy poem entitled ‘HOPE’, Jarman reflects on how:

The virus saps

Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow?

It crosses out

Cancels

You feel apart, so far apart

The others are playing elections37

Composing the tunes

Are they yours any longer?

You watch the argument

From a distance

So near but yet so far

Shall I? becomes

Why bother?

Ten foot under

Am I still part of this?38

Here, Jarman is arguably channelling and individualising the imagery of ‘end times’ that had been insistently projected onto queer people, even before the advent of discourses of HIV and AIDS. The rhetoric of American religious conservatives, which constructed homosexuality as a contagious disease and apocalyptic signifier, its very existence interpreted as a harbinger of impending doom, had identified America itself as a kind of Sodom.39 This language lay behind Anita Bryant’s assault on queer America in the late 1970s, leading the executive director of her Protect America’s Children and Anita Bryant Ministries to observe, in 1984, that the ‘road to ruin for America has been paved by the political homosexual militants … They would lead America to disaster, just as their ancient counterparts led Sodom to its certain doom’.40 Versions of this religiously-inspired invective crossed over to Britain in the 1980s, fuelled not only by the Christian right but by a media bent on sensationalising AIDS both as a punishment for immoral behaviour and as an existential threat to wider society. Coinciding with the release of Jarman’s The Last of England in 1987, the filmmaker’s friend Simon Watney published a ground-breaking study, Policing Desire: Pornography, Aids and the Media. Watney demonstrated that the presence of AIDS among the marginalised groups most exposed to HIV infection was generally perceived, in British news media, as, to quote the book’s first edition, a ‘symbolic extension of some imagined inner essence of being manifesting itself as disease … reinscribed as a property of persons, not a medical syndrome’.41 Furthermore, the view that the spread of AIDS could be attributed principally to gay men indicates ‘the active legacy of moral and theological debates which entirely pre-date the modern period, yet which remain available to make sense of any aspect of contemporary life in a far from fossilised discourse of disease and contagion’.42 In keeping with this, as outlined in another edition of Policing Desire published a decade later, imagery of AIDS in tabloids and on television, which invariably conceived it as a ‘gay plague’, typically imbued the syndrome with a ‘pre-modern’ notion of ‘disease restored to its ancient theological status as punishment’.43 The historical episode most frequently equated with the AIDS pandemic in mass media reporting was the fourteenth-century Black Death, but Watney rejected this apocalyptic logic by speaking frankly about the real-world effects of these misleading analogies, seeing as the duty of everyone involved in AIDS-related work to bear witness to ‘every example of injustice, inhumanity and insult’. Imagining AIDS as an apocalyptic signifier fuelled belief in the inevitability of HIV-related deaths, a state of affairs that Watney attributed to an ‘increasingly degraded, and degrading, mass media news industry’.44

In 1989, Jarman gave a talk in conjunction with an exhibition of his at the Third Eye Centre in Glasgow, commissioned by the National Review of Live Art, which featured a live performance staged within a space that also included large-scale bed installations and walls pasted with tabloid newspaper pages spouting homophobic vitriol. His commentary engaged explicitly with the tropes identified by Watney: ‘Sexuality is treated in the British Isles theologically and pathologically. Attitudes prevail which were laid down in the 12th century … for AIDS is after all a “gay plague”’.45 Furthermore in the early 1990s, again taking stock of analyses such as Watney’s, Jarman had the opportunity, in a series of paintings created for his Queer exhibition at Manchester City Art Gallery (now Manchester Art Gallery), to satirise the press’s role in alienating Britain’s queer communities and disseminating alarmist misinformation about HIV and AIDS. These works, among the last he made, consisted of a ground composed of photocopied headlines from the gutter press, which, aided by assistants, were mounted on canvas and then daubed with paint. Subsequently, Jarman scratched words or slogans into the pigment, variously contesting or amplifying the messages conveyed by the newsprint.46 The lattice of headlines in his 1992 painting Blood, for instance, lifted from a front page of The Sun, read ‘AIDS BLOOD IN M&S PIES PLOT’ (Fig. 10); meanwhile, the title word ‘blood’ is scrawled repeatedly in lower case lettering across the blood-red surface. Jarman was responding, with anger and defiance, to the fear of contagion expressed in the headline and the characterisation of AIDS sufferers as infective plague carriers. But the painting ultimately trades in the same hyperbole as the tabloids Jarman cites. The replication of motifs, perhaps intended to parody an Andy Warhol silkscreen print or a Cy Twombly scribble, serves to immerse the newspaper’s assault on queer identities and bodies in the visual and verbal symbols of the very substance, blood, of which it seemed most afraid.47 Jarman’s reaction to the thinly veiled apocalypticism of British tabloids was to repeat its inflated claims and thereby expose them to critique and ridicule. In At Your Own Risk, published in the same year as he created Blood, Jarman quotes this and other headlines alongside passages of quotation from another voice, the gay press, that presented alternative perspectives. Tellingly, among the litany of queer-baiting slogans, is one that reads simply ‘SODOM AND GOMORRAH’.48

Jarman was keenly aware of the extent to which religiously inspired language filtered into representations of queer people in the tabloid press. His book Queer Edward II, published to coincide with the release of his 1991 film Edward II, uses typography and textual collage to draw explicit parallels between the themes of Christopher Marlowe’s early modern play about the ill-fated medieval king and manifestations of institutional homophobia in modern Britain. Each section from the published shooting script, an adaptation of Marlowe’s original sixteenth-century text, incorporates a slogan that parodies the headline form, while italicised passages in the right margin of the script provide occasions for Jarman and his collaborators to offer their reflections on a given theme. On one page spread, which appears towards the end of the book, Jarman mentions that two newspapers, The Telegraph and The Express, refused to carry a story about him ‘as my open sexuality would offend their readers’; this is followed by a reference to the recently elected Archbishop of Canterbury, George Carey, who pronounced that ‘our sexuality cannot be condoned, only forgiven, by his church’.49 The point of the juxtaposition is to draw out the extent to which British journalism itself was steeped in moralising discourse. Far from being a fully secularised construct in 1990s Britain, the supposedly modern concept of homosexuality continued to be filtered through a religious, quasi-apocalyptic lens whereby queerness was perceived as posing a threat to the nation’s social and moral fabric.

The age-old link between the destruction of Sodom in Genesis and the final Apocalypse thus could be seen re-emerging in modern Britain in the guise of AIDS discourse. Jarman’s response was to counter such imagery through a mix of critique and parodic repetition. This is seen, too, in the two features made after The Last of England that drew most heavily on the Book of Revelation, namely The Garden (1990), conceived as a reworking of the Gospels, and Jarman’s visionary swan song Blue (1993), the three films being conceived as a loose trilogy. Among the most striking sequences in The Garden is a vignette in which a young boy, having danced a flamenco on a table, symbolic of his creative impulses, is surrounded by a group of ageing teachers dressed in academic gowns, who read from books including the Bible, while rapping the table with their canes (Fig. 11); the segment is a prelude to imagery of the flagellation and crucifixion of the gay couple that Jarman has stand in for Christ. The scenes are superimposed onto green screen footage of biblical verses, including extracts from the Book of Leviticus, as well as brooding imagery of the sea and nuclear power stations at Dungeness. Leviticus is presumably invoked due to its condemnation of men who ‘lie with mankind as with womankind’ as an ‘abomination’ (18.9), while the stormy setting of both the education and torture scenes seems to allude to the doom awaiting those who fail to heed the men’s interminable lessons.50 What else but the chastisement of Sodom lies behind such imagery?

Blue itself, meanwhile, derives aspects of its form and language from the Book of Revelation.51 Aside from an unchanging field of International Klein Blue, Jarman eliminated visual referents, thereby challenging viewers to look beyond the threshold of the visible that is traditionally one of the defining features of cinema. Furthermore, Jarman linked this evocation of an anti-mimetic visionary landscape to a sense of apocalypse embedded in his own personal experiences of AIDS: ‘Here I am again in the waiting room’, the voiceover announces, ‘Hell on Earth is a waiting room. Here you know you are not in control of yourself, waiting for your name to be called: “712213”. Here you have no name, confidentiality is nameless. Where is 666? Am I sitting opposite him/her? Maybe 666 is the demented woman switching the channels on the TV’.52 This passage of narration clearly makes direct reference to the Book of Revelation, with its number symbolism and announcement in the thirteenth chapter that 666 is the number of the beast. Later, in one of the film’s final poems, Jarman’s narrator again conceives apocalypse in terms of a direct, personal encounter with the notion of time drawing to a close:

Ages and Aeons quit the room

Exploding into timelessness

No entrances or exits now

No need for obituaries or final judgements

We knew that time would end

After tomorrow at sunrise

We scrubbed the floors

And did the washing up

It would not catch us unawares.53

Returning to The Last of England and analysing it in light of these later works, it is, therefore, worth emphasising that the film’s vision of apocalypse was likely conceived, in part, as a response to the AIDS crisis specifically.

Jarman had become increasingly aware, in the years and months preceding his own HIV diagnosis, of media coverage representing gay men as infective plague-bearers. In Kicking the Pricks, the artist recalls how earlier in 1986, when his doctor had suggested that he take the test, he had visions of featuring in the ‘daily diet of terror’ that sells tabloid newspapers.54 Although the filming itself was completed before Jarman learned of his own HIV status, the editing and sound-synching were undertaken in spring 1987 and the finished film has often been interpreted as registering the personal and cultural significance of AIDS. The soundtrack to a pivotal scene, for example, in which Tilda Swinton, playing a mourning bride, dances against the ruinous backdrop of London’s Docklands, is the song Εξελόυμε (‘Deliver Me’), from Diamanda Galás’s Saint of the Pit (1986), the second instalment in her Masque of the Red Death trilogy memorialising the AIDS crisis. Saint of the Pit is delivered in the voice of the afflicted, drawing on Galás’s experiences of AIDS activism, including the loss of her brother to the disease in 1986, which she described as a ‘personal apocalypse’. The Last of England also alludes to the threat posed by Thatcher’s Conservative Government to marginalised bodies and desires, notably with its imagery of military executions, refugees huddled beside the Thames and despondent young men wandering through a ruinous urban wasteland.55 AIDS is arguably, as such, a significant subtext in the film, a theme that also resonated with Hunt’s The Scapegoat (Fig. 9). Just as the titular beast in Hunt’s painting has been expelled to an inhospitable landscape after being afflicted with the sins and sorrows of the people of Israel—or, as one of the biblical quotations inscribed on the work’s frame has it, ‘the Goat shall bear upon him all their iniquities unto a Land not inhabited’ (Leviticus 16.22)—so the various exiles and scapegoats in Jarman’s film represent the stigmatisation of gay men in Thatcher’s Britain, expelled to the margins and tainted, via their association with a deadly new disease, with the sin of Sodom.56

Despite the film’s seemingly relentless stream of imagery foregrounding decay and desolation, however, Jarman also insisted on the reparative potential of The Last of England as what he called a ‘healing fiction’. Making the point with reference to medieval dream visions, he puts it thus in Kicking the Pricks: ‘In dream allegory the poet wakes in a visionary landscape where he encounters personifications of psychic states. Through these encounters he is healed … The Last of England is in the same form’.57 Supporting this view are the fires seen burning throughout the film (Fig. 12), which variously act as a destructive or infernal force, as in scenes of urban desolation such as footage of the 1981 Brixton riot, and as a source of light and guidance, as in the flares lighting the refugees’ way in the concluding sequence.58 Suggestively, footage filmed along the Thames that takes in manifestations of Thatcher’s ‘new London’—its Docklands, then in the throes of redevelopment, and its thriving City—also focuses, fleetingly, on the Monument to the Great Fire of London in 1666 (Fig. 13), a year many at the time predicted would be the end of the world in view of the date’s numerical significance.59 Intercut with these scenes of London’s financial district is imagery of roaring flames and of a figure representing Babylon allegorically as a fat, bald woman manically spinning a star-covered globe.60 Jarman is likely making reference here to the ‘Whore of Babylon’ in the Book of Revelation, which implies that the City of London, like its biblical counterpart, functions in the film as a symbol of imperialism and unfettered consumerism. Minutes earlier a short sequence featuring footage of the bright lights of Manhattan similarly presents New York City as a kind of Babylon. But the monument to London’s fiery fate also marks a moment of rebuilding and renewal. Just as significant as destruction, in other words, were fire’s associations with cleansing and purgation.

Some years earlier, Jarman had personally experienced fire’s simultaneously destructive, purifying and generative forces. In 1979 a space in Butler’s Wharf, the last of the riverside warehouses that he made his home throughout the 1970s, burnt down shortly after he had moved into a building aptly named Phoenix House on London’s Charing Cross Road. Like the mythical phoenix, Jarman saw himself emerging from his own ashes, as explored in Kicking the Pricks, where he reflects on how the Butler’s Wharf fire—and implicitly fire in general—‘consumed and cleansed, gave power to the imagination, ordeal by fire … Fire runs in rivulets through my dreams, consumes everything in its path’.61

The most memorable scenes in The Last of England harness this sense of purification and rebirth. Footage of an eccentric ‘marriage’, filmed in a decaying warehouse (Fig. 14), shows a woman played by Swinton, dressed in white, celebrating her betrothal to a handsome groom (Jonny Phillips). But instead of the usual wedding march, the musical accompaniment to this strange sequence consists of another extract from Galás’s Saint of the Pit album, a track called La Treizième Revient (The Thirteenth Returns).62 Featuring a sinister synthesised pipe organ, which emits sounds reminiscent of a Requiem Mass, the ominous soundtrack announces that what we are viewing is meant to be interpreted as disconcerting. Adding to this sensation is the inclusion of a pair of bridesmaids in pantomime-style drag. Moreover, the wedding party pushes a pram containing a baby smothered in tabloid newspapers such as The Sun, alluding—as in the paintings Jarman created for the later Manchester Queer show, which featured texts lifted from tabloid headlines and newspaper grounds—to the suffocating climate of moralism and sexual repression that had cast its shadow over British culture in the later 1980s (one of the headlines reads ominously ‘Doom they shared’). Meanwhile, the soundtrack to this sequence also incorporates extracts from coverage of the royal wedding of Prince Andrew to Sarah Ferguson in 1986, suggesting that the ‘marriage’ ceremony in the film also epitomises the apotheosis of what Jarman would later dub ‘Heterosoc’, figured as a prison house of marriage, mortgages, monogamy and biological family.63

In addition, however, these scenes can be interpreted as representing Jarman’s take on chapter 21 of the Book of Revelation, where, after the conquest of Babylon and the casting of Satan into a lake of fire and brimstone, John describes seeing the New Jerusalem ‘coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a bride adorned for her husband’ (21.2); the holy city’s arrival as a bride anticipates Christ’s Second Coming, when, as John continues, God ‘will wipe away every tear from their eyes, and death shall be no more … for the former things have passed away’ (21.4). Except that the wedding sequence in Jarman’s film is followed by another that deliberately stands this imagery on its head. Swinton now appears in a desolate wasteland, in front of a flaming pyre, as she manages to cut her way out of the dress with a pair of sheers, a prelude to her iconic dance in the film’s penultimate scene (Fig. 15). As Jarman comments in Kicking the Pricks, after Swinton’s bride has been ‘blown by a whirlwind of destruction’, she ‘becomes a figure of strength … able to curse the world of the patriots: “God damn you, God damn you all”’.64 Cutting up the dress, Swinton also enacts a version of symbolic cleansing; the process is characterised by Jarman as a ‘shredding’ of illusions. The bridal outfit is represented as a repressive trap from which, against a backdrop of purgatorial fire, the bride liberates herself in anticipation of a final, seemingly more hopeful ending.65Intriguingly, the location in which these sequences were shot is also charged with a millennial resonance by virtue of its title: the building that provided the backdrop to Swinton’s dance and other key scenes in The Last of England, a derelict flour mill in London’s Royal Victoria Dock, is known as Millennium Mills, a name that seems peculiarly apt in light of the site’s role as a setting for Jarman’s treatment of apocalyptic themes.66

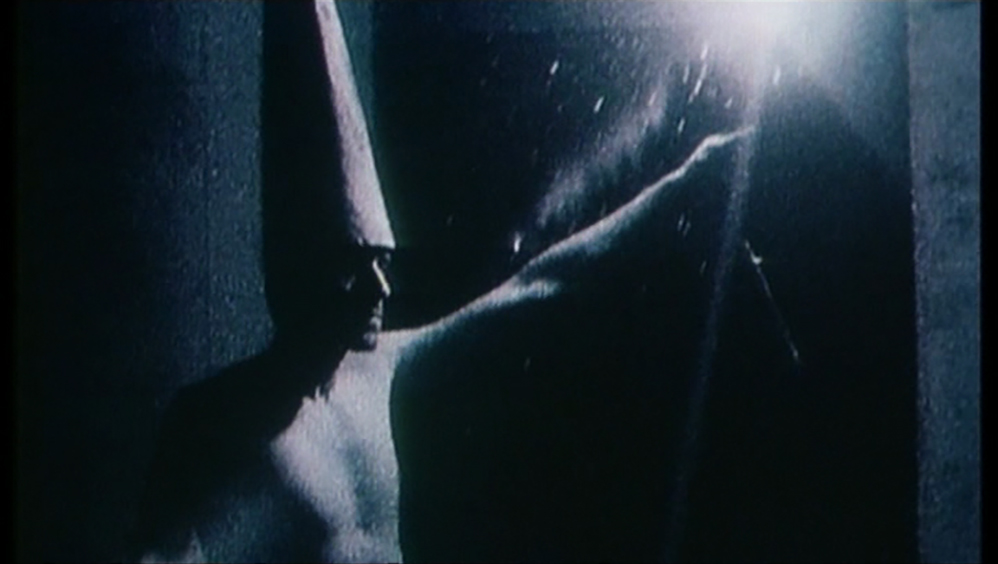

Finally, indicative of the storm’s passing, viewers are confronted with an image of water shimmering beneath a night sky, as the aforementioned refugees steer their boat into the dark unknown (Fig. 8). These concluding scenes convey a distinct mood from the apocalyptic imagery encountered previously. The man who holds a flare to light the vessel’s way, played by Spencer Leigh, had earlier in the film appeared wearing a high conical hat (Fig. 16), which alludes to his status as a heretic, while also carrying a burning torch; those condemned as religious nonconformists in medieval and early modern Europe were often forced to wear pointed paper hats or mitres signalling their disgrace.67 Later Leigh reappears in the guise of a prisoner, being led slowly to his execution by a group of gun-toting and balaclava-clad ‘terrorists’, who are identified by Jarman as representing the Establishment.68 The scene of the prisoner’s death, repeated twice and intercut with footage of Swinton in a field of daffodils, her voice declaring sweetly ‘don’t be sad’, precedes a sequence in which the refugees huddle beside the Thames in London’s Docklands in the shadows of a bonfire, guarded again by terrorists (Fig. 7). Extracts from the footage of the execution also reappear in the segment where Swinton cuts herself out of her wedding gown. But the boat in the concluding sequence perhaps signals that some of those condemned earlier as heretics may finally have eluded the Establishment’s suffocating ideologies, embarking in what Jarman describes, in Kicking the Pricks, as a ‘great calm, after the stormy weather’.69 The refugees do not clearly escape, as such, as do the émigrés in Ford Madox Brown’s painting, who are destined to lead a new life in the colonies. Rather, as with Jarman’s pursuits as a gardener in Dungeness, they seem to embark on a kind of psychic journey in which life is cultivated from the fragments and ruins of what remains after the storm has passed. Similarly, Swinton’s escape from the entrapment represented by her wedding dress alludes to the possibility of a more open future outside such ideological constraints, a future that takes shape within the ruins of the past. If the refugees symbolise both the vulnerability and endurance of those who have experienced the destructive effects of genocidal violence first-hand—and it is worth recalling that societal responses to the AIDS crisis in the 1980s have periodically been characterised as genocide by negligence—then Swinton’s bride expresses a response to war and patriarchal destruction that combines grief with strength, and defiance with empowerment.70

In closing, I wish to bring into sharper focus some of the historical sources that informed Jarman’s vision of apocalypse. In the early 1960s, before embarking on a Fine Art degree at The Slade, Jarman completed a BA in English, history and history of art at King’s College London. This provided the artist with what his biographer, Tony Peake, has called a ‘multifaceted literary compass with which to navigate the coming years’.71 Probably as a result of these studies, Jarman developed a lifelong interest in works of Old and Middle English literature. Here, I will briefly discuss how three such works—the Old English epic Beowulf; a record of visions by the late medieval mystic Julian of Norwich; and a short early English poem known as The Ruin—informed Jarman’s responses to both AIDS and apocalyptic discourse.

As a prelude to this analysis, it is worth stepping back momentarily to reflect on the key motives that lay behind Jarman’s imaginative encounters with the past. Jarman’s art has occasionally been taken to task for its nationalist or patriotic leanings, or accused of trading in conservative varieties of nostalgia.72 While his engagements with history—and more specifically, with premodern texts, from Old and Middle English poetry to Shakespeare and Marlowe—were often filtered through a geographically circumscribed lens, as witnessed in his final choice of title for the film that became The Last of England, this emphasis on literary ‘Englishness’ was ultimately rooted in Jarman’s university studies and the curriculum at King’s in the 1960s. Moreover, rather than treating the past as a repository of dead objects, a stifling ‘fossil culture’ in which everything is ‘now in its place, chronologically’, or mobilising history as a vehicle to fantasise the restoration of some putatively lost homeland, national identity or moral landscape, Jarman treated the past principally as a resource for critiquing and reshaping aspects of the present with a view to imagining more ideal, open and queer futures.73 As he puts it in the screenplay of his 1986 film Caravaggio, which notoriously cultivates anachronism as a representational strategy, his aim is to find ways to ‘present the present past’, thereby drawing attention to the past’s contemporary and future resonances as an alternative to the climate of ‘ersatz historicism, everything in its ordered place’ that he felt characterised more conventional efforts to represent history cinematically.74

Also, it is worth establishing a clear distinction between the forms of nostalgia that drove Margaret Thatcher to claim that her policies and promise of moral regeneration would make ‘Great Britain great again’ and Jarman’s overriding commitment to engaging creatively with the past as a means of critiquing the present and entertaining the possibility of queerer, less prescriptive futures.75 When Thatcher commenced her first term as Prime Minister in May 1979, she stood on the doorstep of 10 Downing Street and famously invoked lines from a prayer attributed to the medieval churchman Saint Francis of Assisi, which resonated with her promise to restore harmony, truth, faith and hope to British life and politics. But while Thatcher herself occasionally had recourse to excerpts from premodern texts, she generally characterised the past as a repository of venerable but lamentably lapsed moral values, ones that she hoped could be resurrected as a means of reversing the so-called ‘permissive society’ that she and her political allies habitually singled out for criticism.76 This moralising agenda also, of course, laid the groundwork for the homophobia peddled by right-wing tabloid media that works such as Jarman’s Queer paintings sought energetically to expose. Conversely, Jarman’s own citations of history tended to be motivated not simply by a desire to resurrect or reconstruct it with the aim of restoring ideas conceived as truth or tradition, but as a means of disrupting and rethinking contemporary regimes of normativity or what he called ‘Heterosoc’. If Jarman’s engagements with the past can be described as nostalgic on some level, then they seem to align more closely with the reflective variety of nostalgia that Svetlana Boym has identified as calling notions of absolute truth into doubt than with the restorative nostalgia that, she suggests, aspires to erase ambivalence, complexity or specificity.77 Jarman’s longstanding efforts to contest simplistic notions of morality such as those witnessed in the reaction against permissiveness in 1970s and 1980s Britain also surely place him in the reflective camp.

The first of the three texts that I wish to highlight as having informed Jarman’s approach to history and apocalypse is the Old English poem Beowulf. Jarman would have encountered Beowulf during his first year at King’s and returned to the text later in life during the making of The Last of England. One of the principal settings for Beowulf’s account of its eponymous, monster-slaying hero is the great Danish mead hall Heorot. Conventionally, mead halls were conceived as spaces for the fostering of community—for the exchange of gifts and stories, and the nurturing of friendships and alliances—but Heorot is presented as a space under attack: Beowulf begins by recounting how the monster Grendel has been undertaking nightly raids on the hall and slaughtering the brave warriors that it shelters. Grendel is subsequently defeated by Beowulf, an event described as an episode of purification after the monster has threatened to undo the social polity by destroying the space in which its most significant bonds were formed. Tellingly, in one of the two translations of Beowulf on Jarman’s shelves in Prospect Cottage, the section of the poem where the hero is tasked with purging the hall of Grendel, is entitled ‘the cleansing of Heorot’.78 From this Jarman derived his sense of The Last of England as facilitating a process of symbolic cleansing, as articulated in the film’s final sequences featuring Swinton’s dance and the exodus of refugees. In Kicking the Pricks, describing The Last of England as an ‘attic’, Jarman compares the film directly with the mead hall:

Think of the mead hall in Beowulf, with the swallow flying through … Think of that mead hall full of the junk of our history, of memory and so on; there’s a hurricane blowing outside, I open the doors and the hurricane blows through; everything is blown around, it’s a cleansing, the whole film is a cleansing.

I need a very firm anchor in that hurricane, the anchor is my inheritance, not my family inheritance, but a cultural one, which locates the film in home.79

In fact, as I have discussed elsewhere at greater length, the image of the mead hall as a refuge from the storm is ultimately inspired by a passage in Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People (completed c.731) rather than Beowulf per se.80 In a chapter recounting the conversion of the kingdom of Northumbria to Christianity, Bede relays how a debate takes place in the Northumbrian court on whether to accept the new faith. The pagan king’s adviser counsels his master to accept the teaching of the Christian missionaries, alluding in a speech to an imaginary episode when a sparrow flies from wintry darkness into the light and safety of a hall. The adviser likens the sparrow’s flight to the lives of humans as they traverse the tempestuous arc of time, using the analogy to make the case that the arrival of Christianity brings with it the prospect of certainty in the face of an indeterminate past and indifferent future.81

Jarman owned a copy of Bede’s history and appears to have derived from this parable a sense that he needs to find his own anchor amid the storm. For Jarman himself, however, the grounding principle is not an otherworldly kingdom of heaven but his cultural inheritance in this world. As Mark Turner has observed, in an insightful analysis of Jarman’s conflation of Bede and Beowulf in his reflections on The Last of England, the industrial interiors that provide the settings for the film’s staged scenes—notably London’s Millennium Mills—could be interpreted as modern-day equivalents to Bede’s hall and Heorot, threatened as they are by the turbulence and destructive impulses that lie beyond but spaces that simultaneously persist as an ‘attic’ of memory and the ‘junk’ of history.82 The mead halls of early medieval literature, like the film’s Docklands locations and the warehouse apartments that Jarman made his home during the 1970s, provide temporary shelter from the storm of history. This demonstrates Jarman’s persistent interest in routing his vision of a ruinous and broken present through fragments of the past. Just as the artist’s garden at Prospect Cottage incorporated materials salvaged from the beach at Dungeness into its structure (Fig. 17), so projects such as The Last of England were grounded in an awareness of literary and cultural history that afforded him with resources through which to defend himself and others from the monsters of materialism and state-sponsored homophobia.

My second example of Jarman’s investment in history as a means of engaging critically with discourses of apocalyptic end time is his engagement with the meditations of a medieval mystic on human suffering. Jarman had first acquired a copy of Julian of Norwich’s A Revelation of Love while he was researching Edward II. His memoir Modern Nature describes, in an entry for 1989, how he reads the text ‘to the gentle whirr of the washing machine’, evoking a domestic sound that Jarman’s companion Keith Collins, nicknamed ‘HB’ in the diaries, found a source of comfort.83 A Revelation comprises a first-person account in English of the visions of a thirty-year-old woman, received in 1373 after a week of debilitating illness from which she almost did not recover. Lying on her sickbed, as the priest comforts her with a crucifix, and as her mother, thinking her dead, moves to close her eyes, Julian—likely named after the church that hosted the cell in which she was later confined as an anchorite—recalls receiving a series of sixteen ‘shewings’ or revelations. Revived by what she sees, Julian lives into old age, expanding the shorter version of her recollections twenty years later into a vivid and complex meditation on what it means to be human. Julian received her visions in the wake of an event commonly interpreted in apocalyptic terms, the so-called Black Death. While she would have been just a few years old at the time of the first major outbreak of plague in England, in 1348–9, there were several other spates of pestilence during Julian’s lifetime including outbreaks in 1361–2 and 1369.84 Significantly, however, while plague was commonly interpreted as punishment for human wickedness, inflicted by an angry, vengeful God, Julian’s text promotes the image of a nurturing, maternal God; the narrator emphasises that, even in a world seemingly poised on the brink of destruction, ‘al shal be wel, and al manner of thyng shal be wele’.85 Some six hundred years after Julian received her revelations, Jarman found comfort in this response to apocalyptic-seeming times, quoting lines from the mystic in a diary entry for December 1989, just a few days before the third anniversary of his HIV test:

Julian says It is today domysday with me, oh dereworthy moder. I sing myself to the bookshops, mind full of the Middle Ages … Everything I perceive makes a song, everything I see saddens the eye. Behind these everyday jottings—the sweetness of a boy’s smile. Into my mind comes the picture of a blood red camellia displaced in the February twilight.

Grete dropis of blode, in this shewing countless raindrops fall so thick no man may number them with bodily witte.86

The words recycled from Julian’s Revelation, including imagery of ‘doomsday’ addressed to God as ‘mother’ and of blood dripping onto Christ’s head like a deluge of rain, preface Jarman’s reflection that: ‘For years the Middle Ages have formed the paradise of my imagination … the blisse that unlocks … something subterranean, like the seaweed and coral that floats in the arcades of a jewelled reliquary’.87 What Jarman takes from Julian’s text is a reassuringly homely image of falling rain, which, while undoubtedly melancholic in its appropriation as a metaphor of intense Christological suffering, releases in Jarman’s mind a deluge of further memories and associations. This medieval woman’s Revelation thus provided Jarman with a critical resource to rethink his own encounters with perceived apocalypse. Julian’s voice, contemplated against the backdrop of the sounds emitted by a modern household appliance, gave him human succour in the face of encounters with events conceived in his own time as a harbinger of doom.

My final example, The Ruin, appears uniquely in a tenth-century anthology of Old English poetry known as the Exeter Book. The poem’s speaker begins by meditating on the glory of a fallen city, its buildings crumbling into ruin. The narrator then conjures a vision of the city’s and its onetime inhabitants’ former glories, its bright halls and bathhouses full of ‘mondrēama’ [human pleasures] and ‘hereswēg’ [sounds of war], which have subsequently succumbed to the vicissitudes of ‘wyrd’ [fate]:

Crungon walo wīde, cwōman wōldagas,

swylt eall fornōm secgrōfra wera;

wurdon hyra wīgsteal wēstenstaþolas,

brosnade burgsteall. Bētend crungon,

hergas tō hrūsan.

[Slaughter was widespread, pestilence was rife,

And death took all those valiant men away.

The martial halls became deserted places,

The city crumbled, its repairers fell,

Its armies to the earth.]88

The quoted passage, from an edition and translation of the poem that Jarman owned, speaks of the role played by ‘wyrd’ or fate in extinguishing human splendour. In the late 1980s, following his HIV diagnosis, Jarman had considered making a film based on The Ruin or The Wanderer. The latter, another poem whose sole witness is the Exeter Book, shares with The Ruin an investment in the meanings to be extracted from a world laid waste; both works are centrally concerned with the motif of fate. In a 1992 diary entry, Jarman contemplated how this concept, as filtered through the prism of early medieval poetry, provided him with a framework for comprehending his illness. Reflecting on a trip to St Bartholomew’s Hospital in London to receive HIV medication via a drip, he recalls being ‘haunted by memories from The Ruin and other Anglo-Saxon poems, fate is the strongest, fate, fated. I resign myself to my fate, even blind fate’.89 Similar words turn up again in a poem incorporated into the narration of Blue, which presents HIV infection as something to be endured not conquered.90 Underpinning these statements is The Ruin poet’s allusion to devastating ‘wōldagas’ [days of pestilence], a tragedy that takes the lives of ‘secgrōfra’ [valiant men]. As already discussed, coverage of AIDS in the British media had initially identified the syndrome as a ‘gay plague’, as if its cause were somehow homosexuality. Responding to these allegations by repositioning them within the frame of Old English poetry, Jarman categorically rejected representations of gay men as culpable plague carriers. Setting aside apocalyptic characterisations of AIDS as a manifestation of moral as well as physical contagion, an idea that also arguably finds a parallel in interpretations of Sodom’s destruction as a punishment for sexual sin, the filmmaker attributed the sufferings he experienced to fate alone.

The Ruin centres on an apocalyptic vision of a city laid waste and emptied of inhabitants. Depictions of devastated urban landscapes similarly loomed large in films such as The Last of England or indeed, in biblical texts such as John’s Apocalypse and the Sodom story. Ultimately, however, as Jarman’s interest in medieval literature demonstrates, there was also a reparative dimension to his engagement with such imagery. For, as I have already hinted, Jarman’s encounters with ruins might aptly be described as melancholic.91 Typically, in psychoanalysis, melancholia is defined as a state of suspended mourning in which the grieving subject refuses to give up on the lost object. Characterised by Freud as an unconscious and generally pathological process, it contrasts with ostensibly more healthy modes of mourning and letting go.92 In an analysis of queer ecological responses to loss, however, the environmentalist Catriona Mortimer-Sandilands has hailed Jarman as an example of an artist who, especially through his engagements with gardens and garden history, deliberately refused to ‘get over’ the multiple losses he experienced.93 Insistently maintaining his grasp of the lost objects for which he grieved, Jarman endeavoured instead, through his various artistic and horticultural pursuits, to highlight the generative potential that can be found even in hostile environments. This essentially ecological project extended to the cultivation of queer lives and sexualities, to their remembering and reanimation in the face of impending threats and the compulsion to forget.

The seaside garden Jarman created in Dungeness explicitly mobilised these strategies (Fig. 18). Planted in a seemingly barren setting, an expanse of shingle—not dissimilar to the Dead Sea shoreline in Hunt’s painting of The Scapegoat—that has often been described as Britain’s only desert, the garden nonetheless teems with vital signs. The inanimate objects positioned within its porous boundaries—sculptures created from pieces of driftwood and rusted metal washed up on the beach, or pebbles arranged in shapes and patterns (Fig. 17)—were conceived, in the first instance, as memorials: reminders of recently departed friends, experiences and sensations. As Jarman remarked in one of his journals, ‘each stone has a life to tell’.94Comparable to the inhospitable environment at Dungeness, HIV attacks creativity, breeding melancholy. Yet the artist’s various gardening and other creative projects, especially towards the end of his life, can be interpreted as an outgrowth of his responses to the virus. They signalled the lingering presence of a life in ruins.95

This, then, was Derek Jarman’s revelation. His responses to media representations of AIDS were filtered, in part, through the lens of medieval texts, which provided him with a vocabulary for resisting the dominant apocalyptic mode whereby a medical condition ended up being reconceived as a punishment for immorality. Moreover, the Middle Ages represented, as he puts it, ‘the paradise of his imagination’, implying that for the artist heaven consisted not in sweeping away the old but in living with and in history. Jarman’s response to the Sodom story similarly challenged apocalyptic readings that treated the city’s decimation by fire and brimstone as a prefiguration of the world’s destruction at the end of time. Instead of simply wallowing in the imagery of doom that such biblical texts engendered, Jarman viewed a work such as The Last of England as a ‘healing fiction’. And the Book of Revelation itself became, in Jarman’s hands, a resource for imagining survival, living with experiences of loss and pain that cannot be simply wiped away.

Notes

This essay partly draws on research conducted at Prospect Cottage between 2014 and 2017. Keith Collins, Derek Jarman’s companion and carer in his final years, kindly granted me access to the library and archive there. I was also accompanied on my first visit to Prospect Cottage by Roger Cook, a contemporary of Jarman’s who appeared in some of his late films and whose subsequent insights and encouragement proved invaluable to my research. Sadly, Keith passed away in 2018 and Roger in 2021 and this article is dedicated to their respective memories.

Citations

1 Gray Watson, ‘An Archaeology of Soul’, in Roger Wollen (ed.), Derek Jarman: A Portrait (London: Thames & Hudson, 1996), p. 43.

2 Roger Cook, in an obituary in Art Monthly 174 (March 1994), characterises Jarman as a Blakean figure who ‘identified the ecstasy of human sexuality with freedom and protested its bondage’ (p. 34). The library at Prospect Cottage includes modern editions of Blake’s The Marriage of Heaven and Hell and The Book of Urizen, as well as several studies of the artist, which Jarman mainly acquired around 1980. For Jarman’s broader engagement with the work of Blake, see Shirley Dent and Jason Whittaker, Radical Blake: Afterlife and Influence from 1827 (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002), pp. 84–7; Mark Douglas, ‘Queer Bedfellows: William Blake and Derek Jarman’, in Steve Clark and Jason Whittaker (eds.), Blake, Modernity and Popular Culture (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007), pp. 113–26; Michael O’Pray, Derek Jarman: Dreams of England (London: British Film Institute, 1996), p. 12.

3 All biblical quotations are from The Holy Bible: Revised Standard Version Containing the Old and New Testaments. Catholic Edition (London: Catholic Truth Society, 1966), an edition of the text that Jarman used and owned.

4 Derrick Sherwin Bailey, Homosexuality and the Western Christian Tradition (London: Longmans, Green, 1955).

5 John Boswell, Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality: Gay People in Western Europe from the Beginning of the Christian Era to the Fourteenth Century (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980), pp. 4 n3, 93–7.

6 Notably Jarman draws on Boswell’s scholarship in Queer Edward II, the companion volume to his film of Marlowe’s play Edward II which charts the downfall of the eponymous medieval king. See further Robert Mills, Derek Jarman’s Medieval Modern (Cambridge: Brewer, 2018), pp. 15–16, 169, 182 n27.

7 Derek Jarman, At Your Own Risk: A Saint’s Testament, ed. Michael Christie (London: Vintage, 1993), p. 4. See also Derek Jarman, Modern Nature: The Journals of Derek Jarman (London: Century, 1991; repr. London: Vintage, 1992), p. 239, comparing the Church of England to the inhospitality of Sodom.

8 See above n3.

9 Valerie Andrews, Robert Bosnak and Karen Walter Goodwin (eds.), Facing Apocalypse (Dallas, TX: Spring Publications, 1987), p. 1 (italics in the original). Jarman acquired the book in December 1987.

10 Jim Ellis, Derek Jarman’s Angelic Conversations (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009), p. 67. See also Steven Dillon, Derek Jarman and Lyric Film: The Mirror and the Sea (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2004), pp. 74–81.

11 Derek Jarman and Lee Drysdale, ‘Neutron’ (1983), in Derek Jarman, Up in the Air: Collected Film Scripts (London: Vintage, 1996), pp. 145–82. See also Tony Peake, Derek Jarman (London: Little, Brown and Co., 1999; repr. London: Abacus, 2001), pp. 291–6, from which the quoted phrase is drawn; Dillon, Derek Jarman and Lyric Film, pp. 84–8; and, on the Jung’s Aeon and the Book of Revelation as sources of inspiration, Derek Jarman, Kicking the Pricks (London: Vintage, 1996), p. 182.

12 Jarman and Lee Drysdale, ‘Neutron’, p. 182. As he acknowledges in Kicking the Pricks, p. 184, however, Jarman was ‘never completely satisfied’ with the film’s ending. On Bob-Up-a-Down, see further Mills, Derek Jarman’s Medieval Modern, pp. 17–19, 42–3.

13 My analysis of the GBH series is based on viewing several of the paintings when they featured in an exhibition at Void Gallery, Derry, ‘The Last of England’ (15 November 2019 to 18 January 2020). I have also benefited from photographs and a condition report supplied by Vic Allen, arts director of the Dean Clough complex in Halifax, where the paintings were on long-term loan between the mid-1990s and c.2013.

14 Peake, Derek Jarman, p. 318.

15 On the latter, see Raphael Samuel, ‘Mrs Thatcher’s Return to Victorian Values’, Proceedings of the British Academy78 (1992): pp. 9–29.

16 Science and Security Board, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 2021 Doomsday Clock Statement, ‘This is your COVID wake-up call: It is 100 seconds to midnight’, accessed 16 September 2021, https://thebulletin.org/doomsday-clock/current-time/. In 1984, the Clock was set at three minutes to midnight.

17 It is beyond the scope of the present essay to address Jarman’s ecological sensibility in greater depth, but it exerts a noteworthy presence also in his journals and published writings, from the threat of nuclear power, as embodied in the reactors at Dungeness and the Chernobyl disaster in 1986, to the blighting of the landscape through insensitive development. See, e.g., Kicking the Pricks, p.130 (reproducing a photograph of a nuclear weapon test in 1953, identified as featuring Jarman’s own father), p. 136 (on the destruction of the landscape through commercialisation and its transformation into ‘heritage’) and p. 239 (on the power stations at Dungeness, Chernobyl and the Hinckley Point reactors). Late large-scale paintings such as Oh Zone and Acid Rain, both from 1992, were also prompted by Jarman’s awareness of the effects of climate change on his activities as a gardener.

18 William Blake, ‘The Ancient of Days’ (1794). Multiple copies of the etching exist but for an example, see Copy D, plate 1, in the British Museum (1859,0625.72), reproduced at https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1859-0625-72. The palette of works in the GBH series also echoes Blake’s painting Satan Calling Up His Legions, c.1800–1805, in the collection of Petworth House, West Sussex, which illustrates a scene from Milton’s Paradise Lost.

19 Michael Charlesworth, Derek Jarman (London: Reaktion, 2011), pp. 94–101. As well as linking to the Hereford mappa mundi, Charlesworth also discusses the Blakean resonances.

20 John Roberts, ‘Painting the Apocalypse’, Art Monthly 75 (April 1984): p. 7, reprinted in Afterimage 12 (1985): pp. 37–8. Roberts also compares what he interprets as a ‘large missile sight circle’ to a photomontage by Peter Kennard (presumably Under the Glass, 1980) in which a map of Britain is anatomised through the lens of a magnifying glass.

21 Jarman, Kicking the Pricks, p. 190, first published as The Last of England (London: Constable, 1987), discussing Böcklin’s Die Totinsel [Isle of the Dead], several versions of which were painted between 1880 and 1901.

22 Jarman, Kicking the Pricks, p. 202. Edgar Allan Poe, ‘The City in the Sea’ (1845), in T. O. Mabbott, The Collected Works of Edgar Allan Poe, volume 1: Poems (Cambridge, MA: Belknapp Press of Harvard University Press), pp. 196–204; an earlier version of the poem had been published in 1831 as ‘The Doomed City’.

23 Jarman, Kicking the Pricks, p. 202.

24 H. G. Cocks, Visions of Sodom: Religion, Homoerotic Desire, and the End of the World in England, c.1550–1850 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017), pp. 202–35, citing F. De Saulcy, Narrative of a Journey Round the Dead Sea and in the Bible Lands in 1850 and 1851, 2 vols, trans. Edward de Warren (London: Richard Bentley, 1853).

25 Cocks, Visions of Sodom, pp. 232–5; Dominic Janes, Picturing the Closet: Male Secrecy and Homosexual Visibility in Britain (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), pp. 87–94.

26 De Saulcy, Narrative, p. 473.

27 William Holman Hunt, journal entry for November 1854, quoted in Carol Jacobi, William Holman Hunt: Painter, Painting, Paint (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2006), pp. 51–2. See also Tom Barringer, Reading the Pre-Raphaelites (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998; rev. edn., 2012), pp. 140–42.

28 See, for instance, a recent statement on the web pages of The Modern House that ‘the phrase “post-apocalyptic” and Dungeness go together like fish and chips’, accessed 9 April 2021, https://www.themodernhouse.com/journal/a-residents-guide-to-dungeness.

29 Jarman, Kicking the Pricks, pp. 190, 193, discussing Ford Madox Brown, The Last of England, 1850s, Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery.

30 Jarman, Kicking the Pricks, p. 164.

31 Jarman, Kicking the Pricks, p. 166. About an hour into Jarman’s The Last of England, the soundtrack also incorporates news coverage referring to James Anderton alongside references to Jesus and snippets of what appears to be evangelical preaching.

32 Debate on second reading of Local Government Act 1986 (Amendment) Bill, published in Lords Hansard 483 (18 December 1986), columns 310–38, accessed 14 April 2021, https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/lords/1986/dec/18/local-government-act-1986-amendment-bill.

33 Lords Hansard 483, col. 310.

34 Lords Hansard 483, col. 325.

35 Another of the film’s working titles, Victorian Values, which shares its title with the inscription on the 1986 work Grievous Bodily Harm, reproduced as Figure 3, similarly conveyed perceived links between the Thatcherite state and ideas of moral crisis. See Jarman, Kicking the Pricks, p.190; and, for an overview of the moral and religious dimensions of Thatcherism, Matthew Grimley, ‘Thatcherism, Morality and Religion’, in Ben Jackson and Robert Saunders (eds.), Making Thatcher’s Britain (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), pp. 78–94.

36 Jarman, Kicking the Pricks, pp. 16–17; Peake, Derek Jarman, p. 376–8.

37 A reference to Thatcher’s re-election campaign in summer 1987.

38 Jarman, Kicking the Pricks, pp. 226, 229. The poem continues for another ninety-nine lines after those quoted.

39 Thomas L. Long, AIDS and American Apocalypticism: The Cultural Semiotics of an Epidemic (New York: State University of New York Press, 2004), esp. pp. 1–21.

40 Quoted in Long, AIDS and American Apocalypticism, p. 8.

41 Simon Watney, Policing Desire: Pornography, Aids and the Media (London: Methuen, 1987), p. 8.

42 Watney, Policing Desire (1987), p. 49.

43Policing Desire: Pornography, Aids and the Media, 3rd ed. (London: Cassell, 1997), p. 156.

44 Simon Watney, Policing Desire, 3rd ed. (1997), pp. 151, 156. In another context, Watney also observes how the spectacle of AIDS was being ‘stage-managed as a sensational didactic pageant’, a dynamic which both fuelled the apocalyptic tone of media discourse and rendered AIDS utterly banal through its appropriation as a tabloid staple, designed to sell newspapers, and as a rallying point for politicians looking to preserve ‘family values’ from the contagion of social, cultural and sexual difference. See Watney, ‘The Spectacle of AIDS’, in Douglas Crimp (ed.), AIDS: Cultural Analysis/Cultural Activism, special issue of October 43 (Winter, 1987): p. 80. On representations of AIDS as apocalypse, see further Peter Dickinson, ‘“Go-go Dancing on the Brink of the Apocalypse”: Representing AIDS. An Essay in Seven Epigraphs’, in Richard Dellamora (ed.), Postmodern Apocalypse: Theory and Cultural Practice at the End (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1995), pp. 219–40.

45 Derek Jarman speaking in 1989, quoted in Karim Rehmani-White, ‘Third Eye Centre Glasgow 1989’, in Seán Kissane and Karim Rehmani-White (ed.), Derek Jarman Protest! (London: Thames & Hudson; Dublin: Irish Museum of Modern Art, 2020), p. 207. On the Glasgow show, see also Melissa Larner (ed.), Derek Jarman: Brutal Beauty, exh. cat., curated by Isaac Julien (London: Koenig Books/Serpentine Gallery, 2008), pp. 71, 74–5.

46 For more on Jarman’s techniques in the Queer and Evil Queen series and the collaborative process of the paintings’ creation, see Joanna Shephard, ‘Painting on Borrowed Time: Jarman’s Media and Techniques’, in Kissane and Rehmani-White, Derek Jarman Protest!, pp. 96–9.

47 On the Warhol/Twombly connections and Jarman’s subversion of modernist aesthetics in this and related paintings, see further Chris Townsend, Art and Death (London: I. B. Tauris, 2008), pp. 91–5.

48 Jarman, At Your Own Risk, p. 111.

49 Derek Jarman, Queer Edward II (London: British Film Institute, 1991), pp. 104–5.