Cecily Hennessy

The Cloisters Cross has puzzled dealers, curators, museum directors, and art historians since it came on the market in the late 1950s.1 Its place of origin, its date, its function, and its mysterious provenance, as well as the complex meanings that can be found in the compilation of its iconography and texts, have led to much speculation. This essay revisits some of these arguments but focuses on material that links the Cross to Germany, especially those parts of it ruled by Henry the Lion (1129–1195), duke of Saxony and Bavaria, a view which has occasionally been aired. He also had considerable ties with England and with Normandy, which may explain some of the echoes of English and northern French work which have been identified on the Cross.

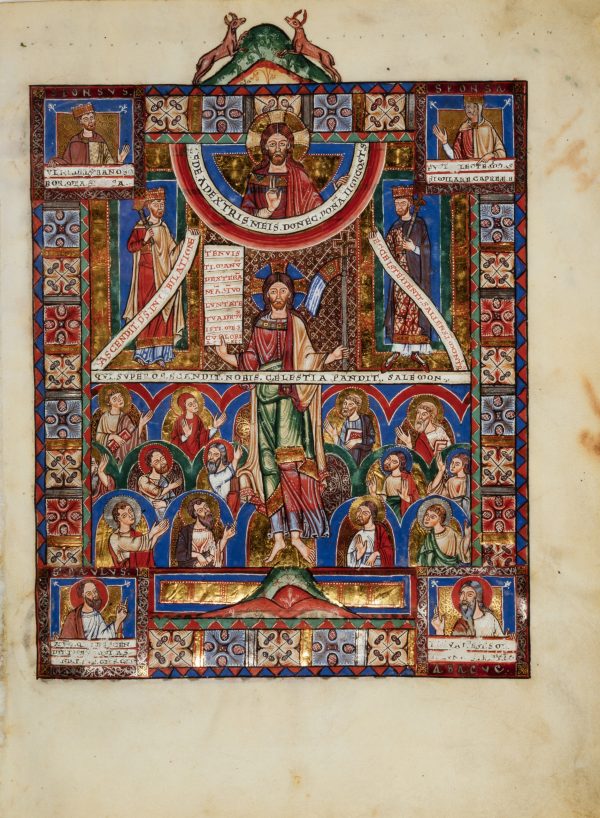

Henry the Lion was the duke of Saxony from 1142 and duke of Bavaria from 1156, titles he inherited from his father, Henry X. His mother was Gertrude of Süpplingenberg, and her parents were the Holy Roman Emperor Lothair II and Empress Richenza. Henry the Lion was a prolific builder and a great patron of manuscripts, reliquaries, crosses, and altars. He ruled over a vast area: Saxony, Bavaria, and also Swabia while married to his first wife Clementia of Zähringen (married 1147; marriage dissolved 1162). His second wife, Matilda, whom he married in 1168, was the eldest daughter of Henry II of England and Eleanor of Aquitaine. They are pictured in a very fine manuscript, made for their church in Braunschweig, known as the Gospel Book of Henry the Lion and Matilda of England (Fig. 6.1).2 Henry the Lion gained land through his inheritances and through grants of territory beyond the Elbe by his cousin Frederick Barbarossa, and secured further territory extending up to the Baltic coast through military campaigns. He refounded both Munich and Lubeck, founded new towns, and gained the right to establish churches and bishoprics in Oldenburg, Mecklenburg, and Ratzeburg.3 He achieved this great power in part by his political and military acumen. However, he lost his titles in 1180 through conflict with Frederick Barbarossa but lived on until 1195.4 Matilda died in 1189.

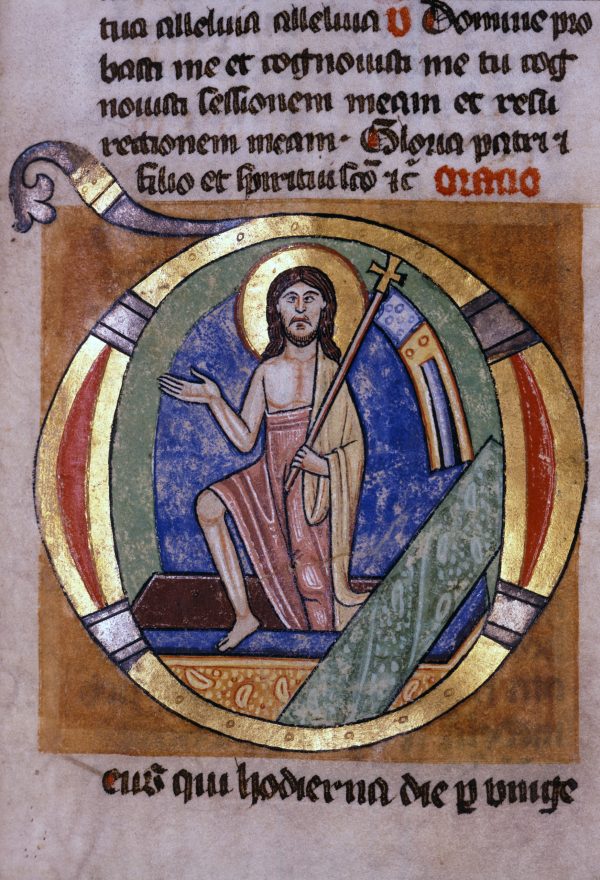

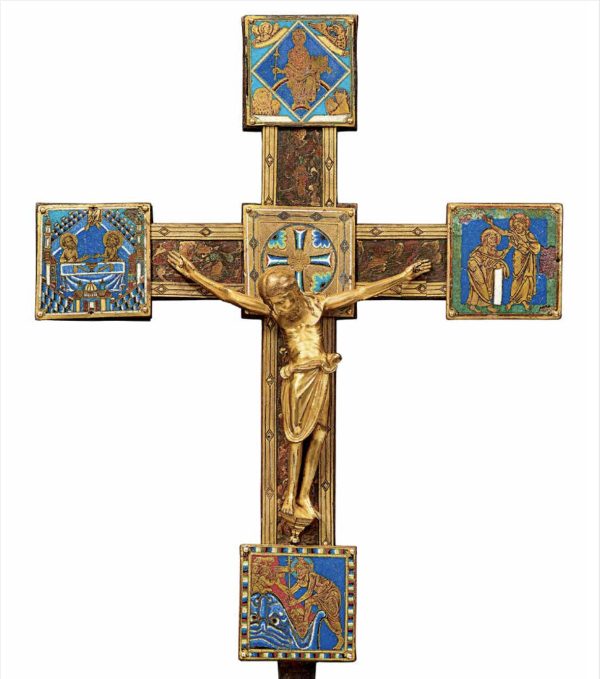

Connecting the Cross with Henry the Lion is not a new idea. The earliest reference I have found is in the archives of the Metropolitan Museum of Art: a scribbled, much corrected draft of a memo dated 2 October 1962 from Thomas Hoving (then curatorial assistant at the Cloisters) to James J. Rorimer (director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art), which reads:Gardner’s text focused on the Easter (Resurrection) plaque, on the front left finial of the Cross, depicting the events of Easter morning (Fig. 6.2). He noted the ‘Continental elements which play such a large part in the rather complex iconography of this scene’.10 On the far left of the plaque, Christ is stepping out of the tomb, as seen in the Ratmann Sacramentary from Hildesheim dated to 1151 (Fig. 6.3).11 Other similar examples show Christ from the side, as in a prayer book possibly made in Winningen in the Mosel valley (Fig. 6.4).12 Gardner maintained that this is also a rare example in the twelfth century of Christ holding a double-armed cross staff as on the Cross. He compared the image on the Cloisters Cross with the Ascension as it appears in a walrus-ivory plaque made in Cologne, now in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, and on a stone font in the Church of St Boniface in Freckenhorst in Westphalia (Figs. 6.5 and 6.6).13

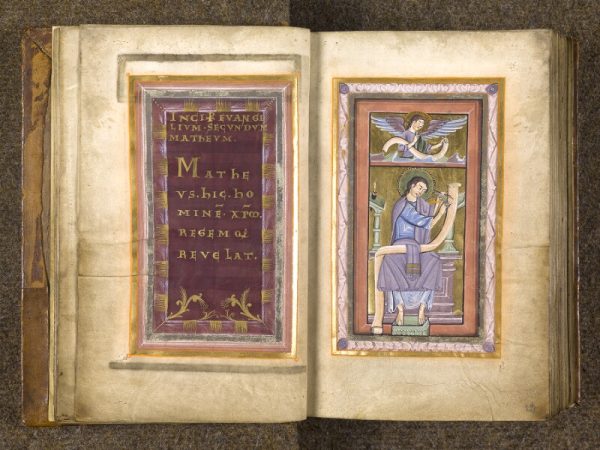

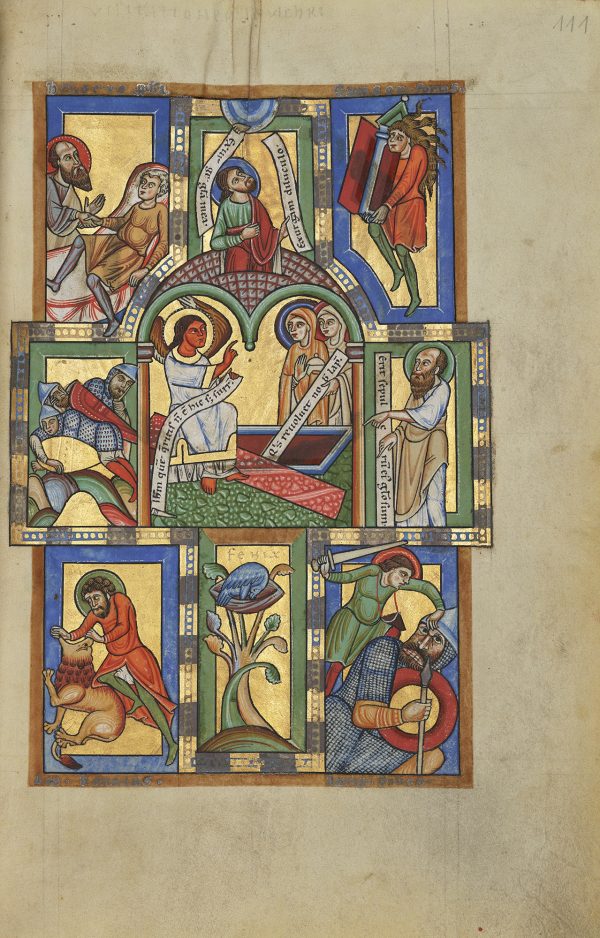

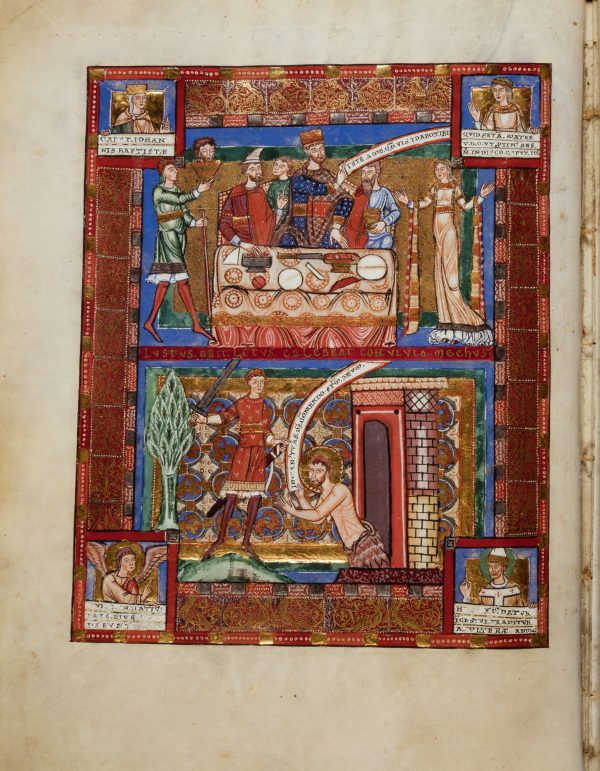

In the adjacent scenes on the plaque are the Maries at the tomb; the angel holding the text from Mark 16:6, Jesum queritis Nazarenum, crucifixum (you seek Jesus of Nazareth who was crucified); and five sleeping soldiers. Gardner associated the form of the angel holding out a scroll with that of St Matthew in German evangelist portraits, such as in an early twelfth-century gospel book made in Essen (Fig. 6.7).14 He argued that angels at the tomb holding scrolls only occurred to a limited degree at this time, and those were often German, such as in the Gospel Book of Henry the Lion and Matilda of England (Fig. 6.8).15

The conflation of the Maries at the tomb and the Resurrection is rare but occurs in two works from Saxony. In the Stammheim Missal, an angel, seated on the tomb, addresses two Maries beneath a baldacchino, while Christ, rising from his tomb, emerges above the baldacchino, looking towards the hand of God (Fig. 6.9).16 On a disk-cross flabellum from Kremsmünster Abbey, which was probably made in Saxony, in the upper left quadrant, the three Maries approach the open tomb in which stands the resurrected Christ (Fig. 6.10).17 This is paired with the Ascension in the upper right quadrant, where Christ is striding to the left, grasping a flagged cross.

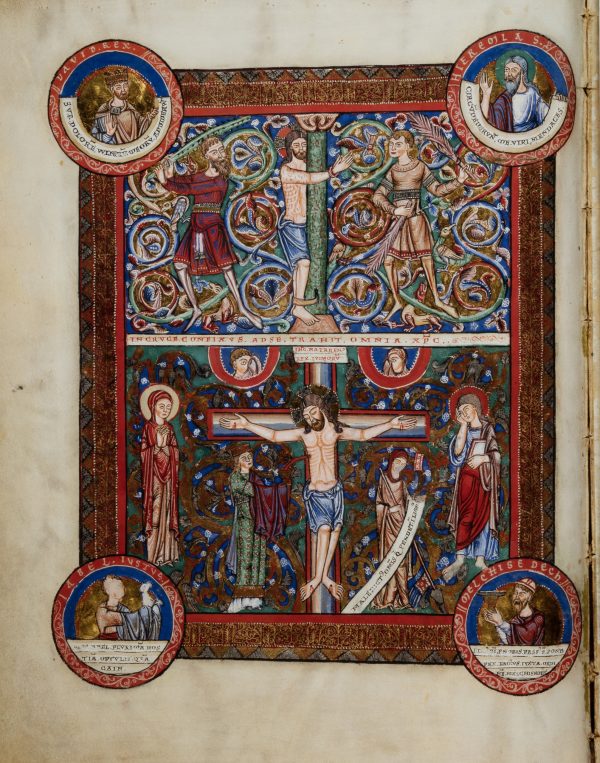

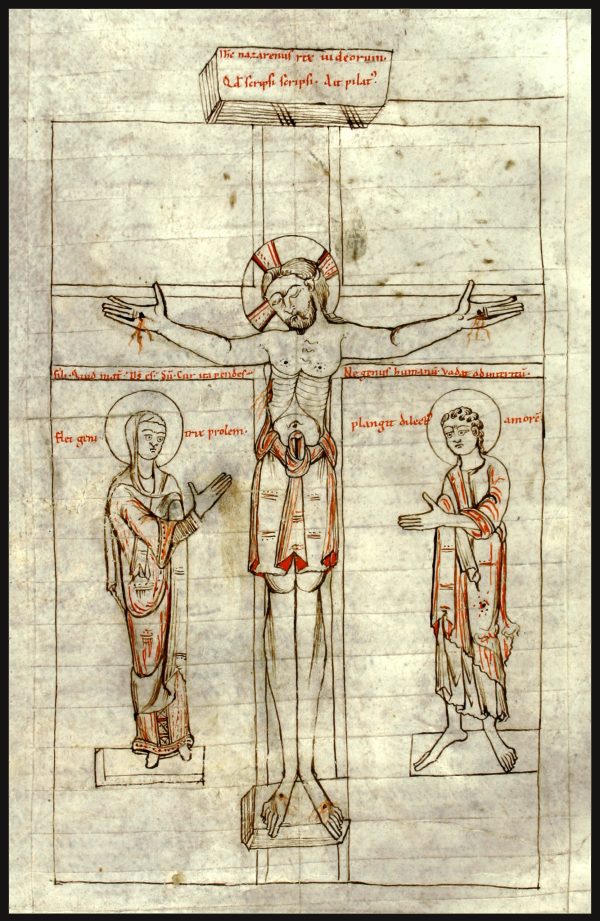

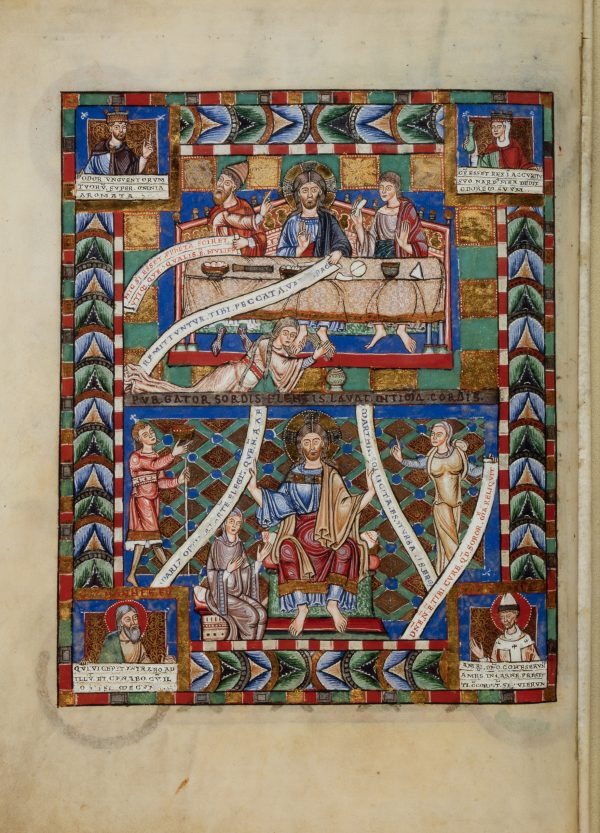

Sabrina Longland cited manuscripts which have German origins as comparisons to the Cross. She showed that in the Crucifixion scene in the Gospel Book of Henry the Lion and Matilda of England, Ecclesia and Synagoga stand on each side of the cross; Synagoga turns away from Christ and holds a spear against the Lamb of God resting beneath her to her left, with his head by the feet of John the Evangelist (Fig. 6.11a–b).18 This motif is also in the back-central medallion on the Cross (Fig. 6.12). In both instances, Synagoga holds a scroll with the inscription Maledictus omnis qui pendet in ligno (Cursed is every one that hangs on a tree) (Galatians 3:13).19 Longland also identified a Crucifixion scene in an eleventh-century psalter from Werden, in which the placard placed over Christ’s head is inscribed in Latin with Q[uo]d scripsi scripsi. Di[xi]t Pilat[us] (What I have written, I have written, said Pilate) (Fig. 6.13).20 Pilate maintained he would not change the epithet on the titulus board reading ‘Jesus King of the Jews’. This rare scene is also on the Cloisters Cross, with Caiaphas and Pilate shown arguing; however, here the words on the titulus above Christ’s head were changed to ‘King of the Confessors’ (Fig. 6.14).

In their very comprehensive study of the Cross published in 1994, Charles Little and Elizabeth C. Parker made several comparisons to Continental and at times specifically German works drawing on similarities between them and the Cross, some of which have already been discussed. They made analogies with the Stammheim Missal and the Kremsmünster flabellum as well as Synagoga and the Lamb image in the Gospel Book of Henry the Lion and Matilda of England.21 They demonstrated the correlation of death with Synagoga and the Church with Life in the Bavarian Uta Codex (ca. 1020), commissioned by Abbess Uta of Niedermünster in Regensburg.22 They pointed out that in the Gospel Book of Henry the Lion and Matilda of England there are numerous figures with testimonial texts. Such texts also appear on the Klosterneuburg altarpiece, formerly the parapet of an ambo, dated to 1181, where typological cycles interweave the Old and New Testaments.23 Between the Descent into Limbo and the Resurrection scenes, David holds a scroll inscribed terra tremuit (the earth trembled), from Psalm 75(76):9.24 Similar words are also found in the couplet starting on the top left side of the front of the Cross, where the complete verse, in translation, reads, ‘the earth trembles (tremit), death defeated groans with the buried one rising, Life has been called, Synagogue has collapsed with great foolish effort’.25

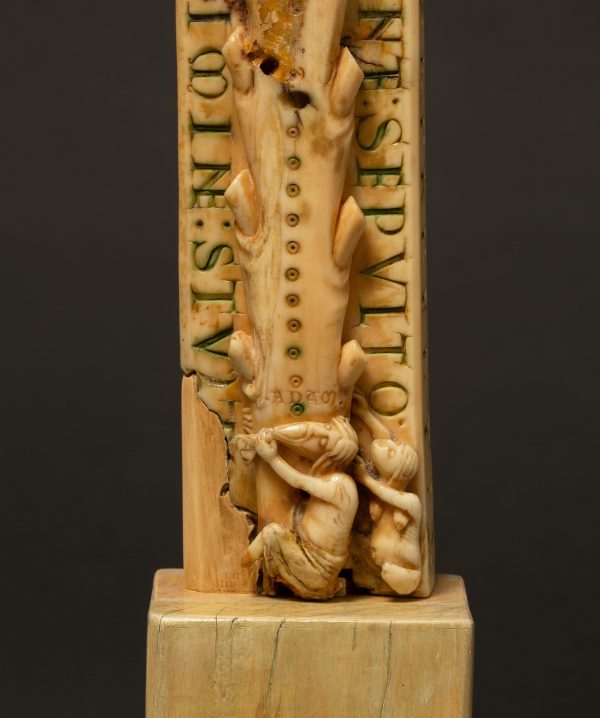

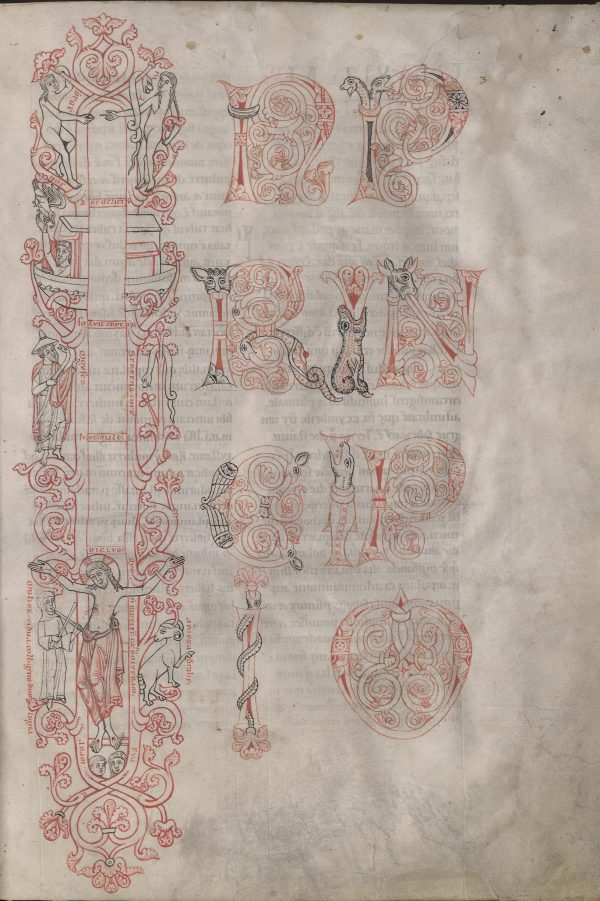

Parker and Little showed that Adam and Eve, at the foot of the Cloisters Cross, are found in the same position in the ivory Crucifixion panel made for Archbishop Adalberus of Metz (984–1005) and in a copy of Flavius Josephus’s Antiquitates Judaicae made in Zwiefalten in 1180 (Figs. 6.15 and 6.16).26 On the same page of the book, Moses is depicted facing the brazen serpent, shown hanging on a forked stick, the theme of the central medallion on the front of the Cross (Fig. 6.17). The Israelites were plagued with snakes, but those who looked on Moses’s serpent were healed (Numbers 21:5–9). Here an analogy is made between Christ raised on the cross and the serpent lifted up by Moses. The serpent hanging over the stick is not common in Romanesque England, and most surviving examples are German.27 An example is in the tenth-century St Gall Sacramentary, where the serpent is suspended on a rough-hewn cross.28 This is also found in a manuscript from Regensburg dated 1170–75.29

In a review of Elizabeth Parker and Charles Little’s monograph, published in 1994, Sandy Heslop pointed out that aspects of the iconography were ‘best attested east of the Rhine’.30 A compelling article by John Munns, published in 2013, made further connections between the Cloisters Cross and the Stammheim Missal, pointing out that the depiction of, for instance, beards and hats are not typical of English examples but are attested in the Missal.31 He suggested that the Cross was more likely to come from the ‘artistic environs of Hildesheim’.32

There are thus several letters, papers, and publications to date which have highlighted correspondences between the Cloisters Cross and work produced in Germany in the eleventh and twelfth centuries. Many of these, as was pointed out by Gardner, come from what can loosely be termed the sphere of Henry the Lion and Matilda in Saxony and in or near Bavaria. There is further material closely associated with Henry and Matilda and the Guelph dynasty and the central lands of their territory in and around Braunschweig which provides close parallels with the Cross.

In 1173, Henry started to build a collegiate church dedicated to Saint Blaise at Braunschweig. The Gospel Book of Henry the Lion and Matilda of England was probably made for the Marian altar in the church, which was consecrated by the bishop of Hildesheim, Adelog (1171–90), in 1188.33 In addition to the scenes of Synagoga piercing the Lamb and the angel holding the scroll at the tomb, there are various other parallels between the Gospel Book and the Cross. In numerous illuminations, key figures hold scrolls with sayings pertinent to the scene depicted. Several images include men wearing pointed hats, as in the scene of Herod’s Feast and Salome’s Dance where one of the guests wears the pointed cap which tilts slightly forward, as seen in two figures to the right of Moses on the central medallion on the front of the Cross (Fig. 6.18).34 This is also, however, worn by Longinus standing with his shield on the far left in the Cross’ Good Friday plaque on the front right finial (Fig. 6.19). In this same plaque, the hat with no forward tilt, worn by the mourner kneeling at Christ’s side and by three figures in the crowd behind Nicodemus (as he removes the nail from the cross), is worn in the Gospel Book by the pharisee to the left of Christ in the scene of Christ in the House of the Pharisee (Fig. 6.20).35 This same hat is worn by two of the shepherds in the Annunciation to the Shepherds, and by the Good Samaritan (Fig. 6.21).36 In contrast, in the scene of John the Baptist Preaching in the Wilderness, two men on the left wear hats with broad brims.37 This is not precisely found on the Cross, although Caiaphas’s hat in the scene with Pilate has a small brim or band around the bottom. Furthermore, the inscribed text running in front of Christ in the page of the Ascension (Fig. 6.22) makes the lower part of Christ very similar to the carved Ascension scene on the Cross (see Fig. 6.14).38 The Gospel Book also features prophets with pointy beards and scrolls, such as Habakkuk and Jeremiah, although on the Cross some of the prophets have short (Malachi) or rounded beards (David, Solomon, Hosea), and in the Gospel Book there are many variations.39

In the church at Braunschweig, Henry the Lion had installed a multifigured, triumphal-cross group in front of the altar of the Holy Cross. This was lost to fire in the nineteenth century, but documents testify to its history.40 Other examples, however, give an indication of its probable appearance. For instance, the thirteenth-century one in Halberstadt Cathedral has similarities with themes on the Cloisters Cross (Fig. 6.23a–c), such as the prophets along the horizontal beam (Fig. 6.24), and Adam at the foot of the cross (see Fig. 6.15).41

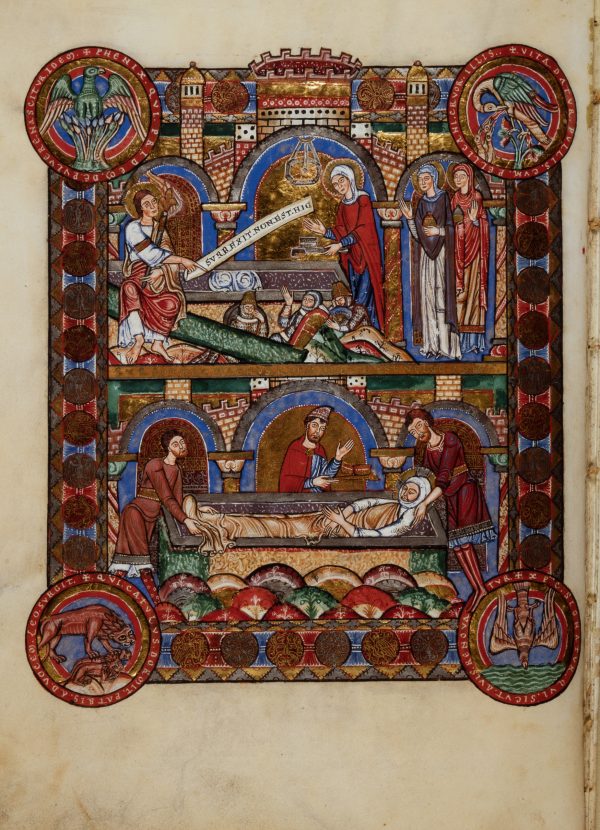

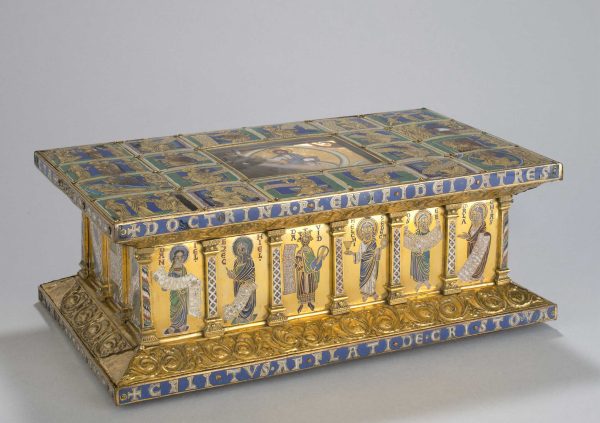

Henry the Lion’s family treasure, known as the Guelph Treasure, was housed in the cathedral at Braunschweig. The collection was started by Countess Gertrude, Henry’s great-grandmother on his mother’s side, in the early eleventh century. It includes a gilt-copper reliquary cross from the eleventh century with standing female figures, who may be Synagoga and Ecclesia, an unusual feature in sculpture of this time.42 The Eilbertus Altar, made in Cologne in the middle of the twelfth century, has enamel figures holding scrolls, very similar to those on the Cloisters Cross, with the prophets with their prophetic texts on the sides and the apostles on the lid (Fig. 6.25a–b).43 It has similar motifs on the lid, such as the soldiers at the foot of the tomb lying head to toe on top of each other, depicted in the far-right panel on the second register and in the Easter plaque on the Cross, or the representation of the Ascension depicted in the lower right panel, borrowed for Christ’s Resurrection in the Easter plaque on the Cross. Christ, though reversed, has the same sideward-facing head, looking up towards the hand of God, with one hand raised and one clasping a cross (although here the cross has a single horizontal bar). Similarly, the elaborate, dome-shaped reliquary, made in Cologne in the late twelfth century from walrus ivory and enamel, has ivory apostles holding scrolls around the dome and standing prophets holding scrolls around the lower register.44 Scrolls appear to be a particularly popular feature in German iconography of this period.

Looking to further objects originating from areas within the sphere of Henry the Lion and Matilda, a processional cross in the Basilica of St Godehard was made in Hildesheim in the last decade of the twelfth century (Fig. 6.26).45 It has been restored and the scenes rearranged. There is an enthroned Ecclesia at the top, an Anastasis or Harrowing of Hell at the bottom, and the Supper at Emmaus on the left. In this, the half figure of Christ in the Ascension is indicated by showing only the lower part of his body clad in a long robe and with naked feet as on the Cross. This form is also used on one of four enamel plaques from an altar table from Hildesheim, dated to the 1180s.46 This type of Ascension, known as the Disappearing Christ, was well-known in England at this time, where it appears to have originated, and clearly had by the 1180s reached Saxony.47

Similarly, a Holy Sepulchre altarpiece made in Saxony or Lower Saxony in the mid-twelfth century again has stylistic and iconographic similarities with the Cross (Fig. 6.27).48 It features Nicodemus, shown here with pliers, and the body of Christ hanging limply next to the Virgin with her arms covered. In terms of secular sculpture, and dated a little later, a vessel made in Hildesheim has a man represented as a Jew in a pointed hat and elongated beard, as on the Cross, and holding what appears to be the three-ball symbol of the pawnbroker. Another man has the rounded headgear and pointed chin also found on men on the Cross, perhaps also indicating someone of Jewish heritage (Fig. 6.28a–c).49

Numerous examples of Ecclesia and Synagoga appear in objects produced in the Hildesheim area.50 For instance, the Crucifixion page from a gospel book, now a single leaf, housed in the Hunt Museum, Limerick, shows Ecclesia to the left of the cross and Synagoga to the far right beyond Saint John. While Ecclesia is crowned and holding a victory flag, Synagoga’s crown is falling through the air and her flag is facing down.51 Her headgear looks like it has slipped as if to cover her eyes and indicate her blindness. Both carry lamps in a reference to the wise and foolish virgins.52 The elaborate book cover of the Gospel of St Godehard from Hildesheim (ca. 1170/80) has an enamel showing Ecclesia to Christ’s right, gathering his blood in a chalice and grasping a pennant, while Synagoga, blindfolded, turns away from him in rejection, with her staff pointing down and her crown falling beside her (Fig. 6.29).53 This image is repeated on an enamel box with a central rectangular panel depicting the Crucifixion.54 A similar rendition is on a semicircular enamel plaque, again from Hildesheim, dated circa 1160/70.55

The Cloisters Cross has often been discussed as an altar cross, the use of which had become widespread by the mid-twelfth century.56 However, the Cloisters Cross probably had a more specific function. It was most likely used during Holy Week, as it includes Old and New Testament readings from the liturgy commemorating Christ’s Passion and Resurrection, as discussed at length by Parker and Little.57 The texts are standard in missals, and some seem to go back to the tenth-century Regularis concordia, drawn up at Winchester in 970.58 This text describes the liturgical enactment when on Good Friday, following the Veneration of the Cross, the cross was wrapped in a linen cloth and taken back to the altar where a ‘sepulchre’ had been prepared and the Depositio crucis was performed. In this, the cross or sometimes the host, a crucifix, or perhaps a figure of Christ was in some way buried. This was followed on Easter Sunday with the Elevatio when this ‘buried Christ’ was ‘resurrected’ and returned to the altar.59 After this, priests enacted the Visitatio sepulchri, the visit of the Maries to the Sepulchre and their dialogue with the angel. It has been shown how this enactment (known as the Quem quaeritis) was well-established in Germany by the tenth and eleventh centuries at Benedictine monasteries, with St Gall, then part of the Holy Roman Empire, providing the earliest text.60 There was a strong tradition of these enactments in Saxony, including at Braunschweig.61

If the Cross were designed to be used in Holy Week, perhaps in a Holy Sepulchre Chapel, then a corpus, which it is generally agreed was attached to the front, could have been removed and buried.62 The Cross can also be easily taken apart, since the top and bottom bars slot into the central medallion, and the side finials are removable (Fig. 6.30). Sometimes an entire crucifix was buried during the Easter liturgy, and it is possible that the Cross would have been taken apart and buried along with the corpus. The iconography on the two plaques at each end of the horizontal bar encapsulate all the elements of the liturgical ceremonies, the Deposition, the Embalming/Burial, the Women Visiting the Tomb, and the Resurrection.

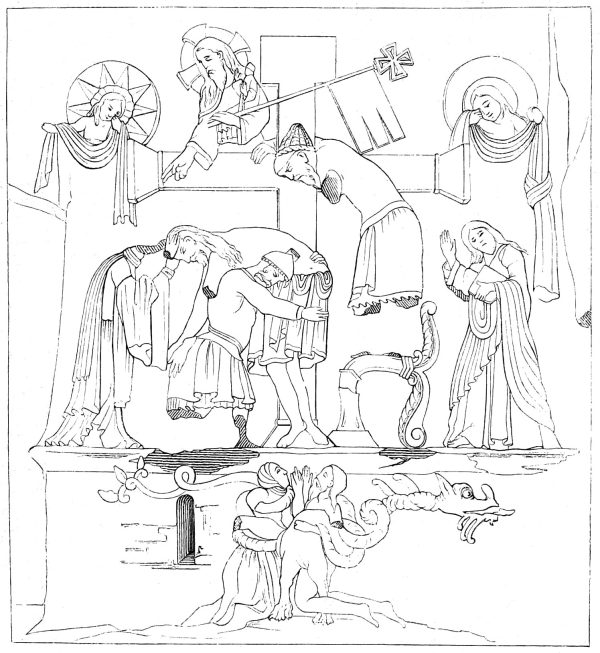

Certain churches had spaces either set aside or particularly suitable for Easter venerations, now known as Holy Sepulchre chapels, as they seem to have been intended to recreate the space of the burial and Resurrection of Christ in Jerusalem. Of these chapels, an early example is the Abbey of Gernrode in Saxony, which was founded for the use of secular canonesses. The abbey had a space in the south aisle that seems to have represented Christ’s place of burial and was by the eleventh century incorporated into two chambers evoking the Holy Sepulchre Chapel in Jerusalem, with sculpture both on its external and internal walls indicating its function.63 Another possible but unusual example is at Externsteine, just a little north of Paderborn. It comprises a complex of three excavated cave spaces seemingly used for Christian ritual, possibly from the tenth but certainly in use in the twelfth century.64 On the external wall of the cave a relief sculpture combines scenes from Christ’s Passion (Figs. 6.31 and 6.32). The date of the carving is disputed, although more recently it has been dated to 1160/1170.65 It depicts the Deposition and the Ascension but also refers to the Crucifixion, with Adam and Eve shown encircled by a snake-like creature at the foot of the cross. This can be compared with Adam and Eve at the foot of the Cloisters Cross, where the snake is not included. In the Externsteine Deposition, Nicodemus to the right of the cross, whose left arm and legs are now lost, has lowered the corpse of Christ into the arms of Joseph of Arimathea to the left of the cross. Beside him is the Virgin and on the far right is Saint John. In the top register, Christ, ascended and holding a victory flag, points down towards the scene. He is flanked by circular representations of the sun and moon. These are similar to those on the Cloisters Cross and are more often found in Crucifixion rather than Deposition scenes.66 The caps worn by Joseph and Nicodemus are like that worn by Nicodemus at the far left of the Good Friday plaque and by the various figures already discussed in the Gospel Book of Henry the Lion and Matilda of England. The sculpture and its setting are unusual but have various elements linking them with the iconography on the Cloisters Cross.

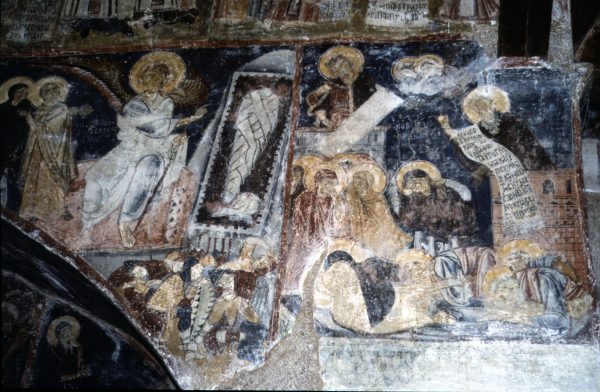

On the Good Friday plaque, Christ appears to be laid not in a sarcophagus but on a stone, the stone of unction. The relic of the stone was taken from Ephesus to the Great Palace in Constantinople in 1169/70 by the Byzantine emperor Manuel I.67 This is one of the earliest representations of the stone of unction in medieval art. In Byzantium, the first extant representation of the stone, perhaps from about 1200, is from the refectory of the Monastery of St John, on Patmos (Fig. 6.33). The scene is labelled Ὁ Ἐπιτάφιος θρῆνος (the sepulchral Lamentation).68 In this scene, as on the Good Friday plaque, there are women mourning Christ, kneeling behind his body with their covered hands raised to their faces in grief. On the Cross, two mourning women hold their uncovered hands to their faces, behind Christ’s embalmed body. This is again a very early, if not the earliest, example of the mourning women with hands to their faces during the Deposition or Lamentation of Christ in Western medieval art.

In Byzantine art, similar iconography occurs in the twelfth century, for instance in a steatite fragment of an icon in the Cleveland Museum of Art where the Mother of God and another woman are mourning next to Joseph of Arimathea at the side of Christ, with what appears to be their hands raised to the sides of their faces (Fig. 6.34).69 Two more women are behind to the left, with their hands raised in grief.70 In other examples from a group of ivories with similar characteristics, often referred to as the ‘frame group’, women to the left of the scene, standing back from Christ, also have their covered hands raised to their faces in mourning.71

As David Park has shown, key points in the Easter liturgical ceremony, the Deposition, the Embalming/Burial, and the Women visiting the Tomb, are included in wall paintings in the Holy Sepulchre Chapel in Winchester Cathedral, dated to the 1180s (Fig. 6.35).72 There is a Deposition in the top register and the Lamentation and Embalming below with the Maries coming to find the angel sitting with the empty tomb, and finally, to the right, the Harrowing of Hell, or Anastasis. The Harrowing of Hell may have been the theme of the lost plaque at the foot of the Cross, although this is disputed.73

There are some similarities between the iconography of the embalmed Christ in both the Winchester paintings and on the Cloisters Cross. In both, Christ appears to be lying on the stone of unction. It is very unusual to find the stone depicted at this date; it is possible that knowledge of it was brought to Winchester by Henry the Lion, who visited Manuel in Constantinople twice in 1172 while en route to Jerusalem and again on his return. Henry the Lion and his family were in Winchester during a period of exile in the 1180s.74 A rare and slightly later use of the stone of unction in an illumination is in the Ingeborg Psalter, made for the Danish queen of France, Ingeborg (1174–1237), who married Philip II in 1193. It was probably made circa 1195–1210.75 Henry the Lion’s daughter Gertrude, born to his first wife Clementia of Zähringen, married Cnut VI of Denmark in 1177 after she was widowed as a young teenager. Cnut was Ingeborg’s brother and so provides a link with the French court, although of course there is no proof of Gertrude’s influence or involvement in making or commissioning the psalter, nor in the Cross.76

Imagery from Saxony and the edges of neighbouring Franconia; from Freckenhorst, Essen, Werden, Cologne, Winningen, Braunschweig, Hildesheim, Halberstadt, Externsteine and Helmarshausen; and from Bavaria and Swabia, Regensburg, Kremsmünster, Zwiefalten, and St Gall, bears many similarities to features of iconography on the Cloisters Cross. In addition to the lands ruled by Henry the Lion and territory added in the Baltic region, he and Matilda spent considerable amounts of time in Normandy and England with Matilda’s family in 1182–85, and Henry also returned to Normandy and England in 1189. He travelled widely during his military campaigns and also on pilgrimage to Santiago, Jerusalem, and Constantinople, in which he celebrated Easter in 1172.77

There is a theory that the Cross was housed in the 1930s in the monastery at Zirc in Hungary and had come there from the abbey at Zsámbék.78 This has connections with Matilda’s family. When she was very young, her eldest surviving brother, Henry, known later as the Young King, married Margaret, the infant daughter of Louis VII of France. After the Young King died in 1183, the widowed Margaret married Béla III of Hungary. He had earlier sought to marry Richenza Matilda, the daughter of Henry the Lion and Matilda of England, who was then living in the court of her grandparents, Henry II and Eleanor. They turned down the marriage proposal, and Béla turned to the hand of their widowed daughter-in-law, Margaret.79 In 1186, Béla granted land at Zsámbék to Aynard, a knight who had escorted Margaret to her marriage in Esztergom, and on this land, which became a place of burial for the family, an abbey for the Premonstratensians, a branch of the Augustinians, was built from about 1220.80 This is, of course, after the Cross is thought to have been made, and the truth or falsity of the provenance of the Cross from Zsámbék abbey via Zirc monastery will probably never be determined, along with the answers to many of the other questions that remain about the Cross’ origins. However, the potential connections of the family of Henry II and Eleanor, their sons and daughters, and the siblings’ spouses with the Cloisters Cross indicates how far-reaching that family’s influences were, filtering through the court and ecclesiastical circles of the rulers of the Western world. This includes their involvement in the rapidly expanding cult of Saint Thomas Becket, which has been associated with the ‘Channel Style’ and so with the Cloisters Cross.81

While Georg Swarzenski argued for parallels between objects in Henry the Lion’s orbit and English work, Neil Stratford warned against linking surviving objects to well-known names, ignoring the lesser-known people in their retinues, the extent of their travels, and the numerous commissions by men of the church.82 It has been emphasised by many who have speculated about the Cross that the complex selection of iconography and texts are the work of an expert in religious doctrine.83 What are the connections with Saxon men of learning? Longland identified the Parisian writings from the circles of Richard of Saint-Victor and Peter Comestor as sources for the Cham ridet couplet and, as she indicated, their learning was widely disseminated.84 Parker and Little looked to Theophilus, possibly the Benedictine monk Roger of Helmarshausen, the author of De diversis artibus, as a prime example of a learned religious man and a skilled artisan.85 They also pointed to the influence on the Cross of Hugh of Saint-Victor and the Victorines, attributing to him links between Jewish and Christian learning and a bridge between the monastery and cathedral schools.86 Hugh was of Saxon heritage, having been educated at the Augustinian Priory of Saint Pancras at Hamersleben, near Halberstadt, before going to Paris.87

Hildesheim was particularly prosperous in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries because of the flourishing mining sites in the Harz mountains, which were part of the diocese. The city also became a great centre of metalwork, all testifying to the extreme wealth available. Bishop Bruno (1153–61) had donated large numbers of books to the cathedral. The library was the third largest in Europe and shared its collection with other institutions.88 It was a vibrant centre of learning and had a renowned cathedral school with close ties to the intellectual centres in Paris. Gerhard Lutz attributed the religious zeal and generous patronage to competition to elevate two bishop saints and the churches connected to them: Godehard (1022–1038), canonised in 1131, and Bernward (993–1022), canonised in 1192. Lutz emphasised the links with France, for instance in the design of the Benedictine Basilica of St Godehard, founded by Bernhard bishop of Hildesheim in 1133, with an ambulatory and radiating chapels.89

This cultural and theological centre at Hildesheim and the extensive patronage of Henry the Lion at Braunschweig recommend the area as a likely milieu for the making of the Cloisters Cross. It is possible that Adelog, bishop of Hildesheim, was the clerical mind behind the iconography on the Cross. Both he and his predecessor, Bernward of Hildesheim, had connections with Paris.90 He came from a noble family related to the Lords of Dorstadt in Lower Saxony. He was at the cathedral in Hildesheim from the early 1160s as a canon and was provost in Goslar and bishop of Hildesheim from 1178 until his death in September 1190.91 Adelog was behind some major building projects in the area, including the completion of the Basilica of St Godehard, Hildesheim; the construction of the Neuwerk monastery in Goslar; and the restoration of St Michael’s Church, Hildesheim, after the fire of 1186. This church, of course, was closely associated with Bernward and was the home of both the Ratmann Sacramentary and the Stammheim Misssal. Adelog also founded an Augustinian nunnery in Dorstadt in 1189. In the disputes between Frederick Barbarossa and Henry the Lion, Adelog kept a foot in both camps before finally siding with the emperor but was clearly on good terms with Henry, since he dedicated the Marian altar in Braunschweig in 1188. It was at this time, it has been suggested, that the Gospel Book of Henry the Lion and Matilda of England was given to the church. The making of the Cloisters Cross may be contemporaneous with the gift of the Gospel Book, indicating a date for the Cross of circa 1188.

Gardner focused only on the Easter (Resurrection) plaque and concluded that, although no firm connection between Henry the Lion and the Cloisters Cross could be made, his influence could be identified in its production, even if only indirectly.92 Instead, this essay has looked at the Cross as a whole and several features of its iconography, comparing them with previously published German imagery. These comparisons have been supplemented with others, including additional scenes from Henry and Matilda’s Gospel Book, illuminations from other manuscripts, objects from the Guelph Treasure, pieces of sculpture, a relief from Externsteine, and various objects associated with the church at Braunschweig, all closely linked to Henry and Matilda or their heartland. Their strong connections with England and with northern France may also account for those elements on the Cross which have been associated with English and ‘Channel Style’ work. The accumulated evidence, while by no means conclusive, certainly indicates a strong argument for links between the Cloisters Cross, Henry the Lion and Matilda, and their sphere.

Citations

[1] I am grateful to the Society of Antiquaries for a Philips Grant which enabled research in the United States, and to Tony Eastmond and Liz James, who supported my application for funding, as well as Christine Brennan, Michael Carter, and Susan Hernandez, who made study possible at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Cloisters, and the Cleveland Museum of Art. I also would like to thank Chuck Little for his warm hospitality and Shirin Fozi and Julia Perratore at the Metropolitan Museum who kindly organised close viewing of the Cloisters Cross and who have been very generous with their time and support for this project and arranged for us to use new photographs of the Cross. I also am indebted to Gerhard Lutz for assistance in research at the Cleveland Museum of Art, and to Sandy Heslop and Richard Plant who both have encouraged my work on the Cross.

[2] Gospel Book of Henry the Lion and Matilda of England, ca. 1188, Cod. Guelf. 105 Noviss. 2°, fol. 171v, Herzog August Bibliothek, Wolfenbüttel (cited hereafter as Cod. Guelf. 105 Noviss. 2°, HAB, Wolfenbüttel).

[3] Karl Jordan, Henry the Lion: A Biography, trans. P. A. Falla (Oxford: Clarendon, 1986), 45–46, 66.

[4] For Henry’s life, see Jordan, Henry the Lion; on Henry’s Baltic lands, see Jordan, 66–88. See also Austin Lane Poole, Henry the Lion (Oxford: Blackwell, 1912).

[5] Memo from Thomas Hoving to James Rorimer, 2 October 1962, Cloisters Cross, file 1, Correspondence 1956–April 1963, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. The phrase ‘is in some way’ is altered from ‘must must have roots in’. According to Kay Rorimer, the suggestion that the Cross came from Bury was originally made to James Rorimer by Harry Bober of the Institute of Fine Arts in 1963. See Kay Rorimer, ‘Trésor de l’art roman anglais: La croix du Cloister à New York’, Estampille, February 1988, 54 (held in folder 11, box 11, Cloisters Cross Research Papers, subseries IIC: KSR Manuscript Drafts, Cloisters Library and Archives, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York). George Zarnecki was then deputy director of the Courtauld Institute. On this, see also Charles Little’s essay in this volume.

[6] Swarzenski to Thomas Hoving, 2 a.m., Easter Sunday [14 April 1963], Cloisters Cross, file 1, Correspondence 1956–April 1963, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. The 1963 date is presumed, as it appears to have been written shortly after the purchase of the Cross by the Metropolitan Museum. See Cod. Guelf. 105 Noviss. 2°, HAB, Wolfenbüttel; and Stammheim Missal, Hildesheim, 1170s, MS 64, J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

[7] Reiner Haussherr, ‘Zur Datierung des Helmarshausener Evangeliars Heinrichs des Löwen’, Zeitschrift des deutschen Vereins für Kunstwissenschaft 34 (1980): 3–15; and Elizabeth C. Teviotdale, The Stammheim Missal (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2001).

[8] Typed seminar paper, autumn 1971, and handwritten notes for a paper given at the Frick, April 1973, William Stephen Gardner Papers, Cloisters Library and Archives, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. The seminar paper ‘Consurget Homo: The Iconography of the Resurrection Plaque on the Walrus Cross in the Cloisters’ was given in a seminar on iconography at Princeton University. Elizabeth Parker referred to the giving of this paper but not to the existence of its text. See Elizabeth C. Parker, ‘Editing the “Cloisters Cross”’, Gesta 45, no. 2 (2006): 149, 156n14.

[9] My thanks to Roberta Olsen for her email conversations, including one on 22 April 2022.

[10] A quote from Gardner’s handwritten paper given at the Frick, April 1973, p. 1, William Stephen Gardner Papers, Cloisters Library and Archives, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

[11] Ratmann Sacramentary, DS 37, fol. 75r, Dom-Museum, Hildesheim (donated to St Michael’s in 1159); and Michael Brandt, ed., Abglanz des Himmels: Romanik in Hildesheim; Katalog zur Ausstellung des Dom-Museums Hildesheim, 2001 (Regensburg: Schnell & Steiner, 2001), 3.9.

[12] Cod. 2739, fol. 65v, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna (dated to the second half of the twelfth century).

[13] No. 378-1871, Victorian and Albert Museum, London; and see Paul Williamson, Medieval Ivory Carvings: Early Christian to Romanesque (London: V&A Publishing, 2010), no. 73 (baptismal font, late twelfth–early thirteenth century, Collegiate Church of St Boniface, Freckenhorst).

[14] Frontispiece from the Gospel of Matthew, Quattuor Evangelia, 1105–13, Ms 16, fol. 2r, Bibliothèque du Musée Condé, Chǎteau de Chantilly, Chantilly.

[15] Cod. Guelf. 105 Noviss. 2°, fol. 74, HAB, Wolfenbüttel; and Jochen Luckhardt and Franz Niehoff, eds., Heinrich der Löwe und seine Zeit: Herrschaft und Repräsentation der Welfen 1125–1235: Katalog der Ausstellung Braunschweig 1995, vol. 1 (Munich: Hirmer, 1995), cat. no. D31, 206210; Horst Fuhrmann and Florentine Mütherich, eds., Das Evangeliar Heinrichs des Löwen und das mittelalterliche Herrscherbild: Ausstellung, 18. März–20. April 1986 (Munich: Prestel, 1986), plates 27–30; and Ingrid Baumgärtner, ed., ‘Kronen im Goldglänzenden Buch: Mittelalterliche Welfenbilder und das Helmarshausen Evangeliar Heinrichs des Löwen und Mathildes’, in Helmarshausen: Buchkultur und Goldschmiedekunst im Hochmittelalter (Kassel: Euregioverlag, 2003), 33–34, 123–46.

[16] Stammheim Missal, Hildesheim, 1170s, MS 64, fol. 111, J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

[17] Gilt-copper disk-cross flabellum, ca. 1170–80, Kremsmünster Abbey, Kremsmünster. Swarzenski, however, suggested the flabellum could be English. See Hanns Swarzenski, Monuments of Romanesque Art (London: Faber and Faber, 1954), 64, fig. 321.

[18] Cod. Guelf. 105 Noviss. 2°, fol. 170v, HAB, Wolfenbüttel; and Sabrina Longland, ‘The “Bury St. Edmunds Cross”: Its Exceptional Place in English Twelfth-Century Art’, The Connoisseur 172 (1969): 168.

[19] Longland, ‘Bury St. Edmunds Cross’, 172; and Teviotdale, The Stammheim Missal, fig. 46b.This quote also appears on the Stammheim Missal, fol. 86 (the Crucifixion). See Elizabeth C. Parker and Charles T. Little, The Cloisters Cross: Its Art and Meaning (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1994), 267n96.

[20] MS 14, fol. 9v, Stadbibliothek, Trier; and Sabrina Longland, ‘Pilate Answered: What I Have Written I Have Written’, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 26, no. 10 (1968): 412, 414, fig. 4.

[21] For the Stammheim Missal, see Parker and Little, Cloisters Cross, 86, fig. 58; for the flabellum, see Parker and Little, 86.

[22] Uta Codex, Clm 13601, fol. 3v, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich; and Parker and Little, Cloisters Cross, 56, ill. 130.

[23] Parker and Little, Cloisters Cross, 97.

[24] On this, see Harcourt-Smith’s essay in this volume.

[25] Parker and Little, Cloisters Cross, 241.

[26] The Adalberus ivory, dated before 1005, is located today in the Musée de la Ville, Metz. See also Parker and Little, Cloisters Cross, 139, fig. 125. For Antiquitates Judaicae, see MS Hist 2° 418, fol. 3, Württembergische Landesbibliothek, Stuttgart; and Parker and Little, Cloisters Cross, 52, fig. 27. The iconography of the Zwiefalten Antiquitates is also mentioned in a letter from Hanns Swarzenski to Thomas Hoving, dated 14 April 1963, held in the archives of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

[27] Parker and Little, Cloisters Cross, 62–63.

[28] St Gall Sacramentary, MS 342, fol. 281, Stiftsbibliothek, St Gallen; and Parker and Little, Cloisters Cross, 62, fig. 38.

[29] Dialogus de laudibus sanctae crucis, 1170–75, MS Clm. 14159, fol. 3, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich; and Parker and Little, Cloisters Cross, 62.

[30] T. A. Heslop, Review of The Cloisters Cross: Its Art and Meaning, by Elisabeth C. Parker and Charles T. Little, The Burlington Magazine 136, no. 1096 (1994): 459.

[31] John Munns, ‘Relocating the Cloisters Cross’, The Burlington Magazine 155, no. 1323 (2013): 381–83.

[32] Munns, ‘Relocating the Cloisters Cross’, 383.

[33] Jordan, Henry the Lion, 201. For discussion of the dating of the manuscript, see Jitske Jasperse, Medieval Women, Material Culture, and Power: Matilda Plantagenet and Her Sisters (Baltimore: Arc Humanities Press, 2020), 69–70, 69n11, 70n12.

[34] Cod. Guelf. 105 Noviss. 2°, fol. 73v, HAB, Wolfenbüttel.

[35] Cod. Guelf. 105 Noviss. 2°, fol. 111v, HAB, Wolfenbüttel.

[36] Cod. Guelf. 105 Noviss. 2°, fols. 111r, 112r, HAB, Wolfenbüttel.

[37] Cod. Guelf. 105 Noviss. 2°, fol. 74r, HAB, Wolfenbüttel.

[38] Cod. Guelf. 105 Noviss. 2°, fol. 75r, HAB, Wolfenbüttel.

[39] Cod. Guelf. 105 Noviss. 2°, fol. 170v, HAB, Wolfenbüttel.

[40] Gerhard Lutz, Das Bild des Gekreuzigten im Wandel: Die sächsischen und westfälischen Kruzifixe der ersten Hälfte des 13. Jahrhunderts (Petersberg: Imhof, 2004), 90–92.

[41] Lutz, Das Bild des Gekreuzigten im Wandel, 24, 75–106.

[42] Inv. no. W10, Kunstgewerbemuseum, Berlin; W. A. Neumann, Der Reliquienschatz des Hauses Braunschweig-Lüneburg (Vienna: Alfred Hölder, 1891), no. 4; and The Guelph Treasure: Catalogue of the Exhibition (Cleveland, OH: Cleveland Museum of Art, 1931), no. 16. On the Guelph Treasure, see also Patrick M. de Winter, ‘The Sacral Treasure of the Guelphs’, Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art 72, no. 1 (1985): 2–160.

[43] Inv. no. W11, Kunstgewerbemuseum, Berlin; Neumann, Der Reliquienschatz, no. 19; and The Guelph Treasure, no. 17. On the relation of the technique, style, and motifs of the Eilbertus Altar to Byzantine art, see Krijna Nelly Ciggaar, Western Travellers to Constantinople: The West and Byzantium, 962–1204; Cultural and Political Relations (Leiden: Brill, 1996), 236.

[44] Inv. no. W15, Kunstgewerbemuseum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin; Neumann, Der Reliquienschatz, no. 23; and The Guelph Treasure, no. 22.

[45] Basilica of St Godehard, Hildesheim, 1190s; Brandt, Abglanz des Himmels, 4.27; Luckhardt and Niehoff, Heinrich der Löwe und seine Zeit, vol. 1, no. G33; and Gerhard Lutz, ‘Ein Hildesheimer Vortragekreuz mit Grubenschmelzen’, Aachener Kunstblätter 60 (1994): 223–36.

[46] Inv. no. DS 30, Dom-Museum, Hildesheim; and Brandt, Abglanz des Himmels, 4.11.

[47] See Meyer Schapiro, ‘The Image of the Disappearing Christ: The Ascension in English Art around the Year 1000’, Gazette Des Beaux-Arts 23 (1943): 133–52; and Robert Deshman, ‘Another Look at the Disappearing Christ: Corporeal and Spiritual Vision in Early Medieval Images’, The Art Bulletin 79, no. 3 (1997): 518–46.

[48] KG 159, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg. See also Luckhardt and Niehoff, Heinrich der Löwe und seine Zeit, vol. 1, D44.

[49] Aquamanile, 1200–1220, Inv. no. 1959.307, Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe, Hamburg.

[50] For a summary, see Brandt, Abglanz des Himmels, 142.

[51] Crucifixion page from a book of Pericopes, Hildesheim, twelfth century, L 006, The Hunt Museum, Limerick; and Brandt, Abglanz des Himmels, 3.8b.

[52] Brandt, Abglanz des Himmels, 133.

[53] Cod. 141 (olim 126), Domschatz no. 70, Hohe Domkirche, Trier; and Brandt, Abglanz des Himmels, 4.7.

[54] Enamelled pyx, Hildesheim, ca. 1170/80, inv. no. CMA 1949.431, Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland; and Brandt, Abglanz des Himmels, 4.34.

[55] Inv. no. Cl 13068, Thermes de Cluny, Musée National du Moyen Age, Paris; and Brandt, Abglanz des Himmels, 4.18a.

[56] For a representation of a cross on an altar, see New Minster Liber Vitae, Winchester, ca. 1031, MS Stowe 944, fol. 6r, British Library, London. See also Wiltrud Mersmann, ‘Das Elfenbeinkreuz der Sammlung Topić-Mimara’, Wallraf-Richartz-Jahrbuch 25 (1963): 13, fig. 6; Longland, ‘The “Bury St. Edmunds Cross”’, 163; and Parker and Little, Cloisters Cross, 136, fig. 122.

[57] For a detailed recounting of the liturgical events in Holy Week and Easter Week, see Parker and Little, Cloisters Cross, 149–73.

[58] Thomas Symons, ed. and trans., The Monastic Agreement of the Monks and Nuns of the English Nation [Regularis concordia Anglicae nationis monachorum sanctimonialiumque] (London: Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1953); and Justin Kroesen, The Sepulchrum Domini Through the Ages: Its Form and Function (Leuven: Peeters, 2000), 153–56. For references to such ceremonies at Winchester and elsewhere, see David Park, ‘The Wall Paintings of the Holy Sepulchre Chapel’, in Medieval Art and Architecture at Winchester Cathedral: The British Archaeological Association Conference Transactions for the Year 1980, ed. T. A. Heslop and Veronica Sekules (London: British Archaeological Association, 1983), 60n102; and T. A. Heslop, ‘A Walrus Ivory Pyx and the Visitatio Sepulchri’, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 44 (1981): 157–60. On the development and understanding of the ritual, see Melanie Laura Batoff, ‘Re-Envisioning the Visitatio Sepulchri in Medieval Germany: The Intersection of Plainchant, Liturgy, Epic, and Reform’ (PhD diss., University of Michigan, 2013), 21–40.

[59] Symons, Monastic Agreement [Regularis concordia], 42–45; and Parker and Little, Cloisters Cross, 156–57.

[60] On St Gall, see Helmut de Boor, Die Textgeschichte der lateinischen Osterfeiern (Tübingen: Max Niemeyer, 1967), esp., 23, 30–39, 48–52; for a summary of early developments of the Quem quaeritis, see Boor, 67–68. See also Batoff, ‘Re-Envisioning the Visitatio Sepulchri in Medieval Germany’, 42.

[61] Dunbar H. Ogden, The Staging of Drama in the Medieval Church (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2002), 41–51; on Braunschweig, see Ogden, 912–13n9. See also Walther Lipphardt, ed., Lateinische Osterfeiern und Osterspiele, vol. 5 (Berlin: De Gruyter, 1975), 1489–1501.

[62] On a corpus attached to the front of the Cross, see, with a summary of the arguments, Parker and Little, Cloisters Cross, 30–33; on the Oslo Corpus, see Parker and Little, 37, 159, 253–260. For a different view on the Oslo Corpus, see T. A. Heslop’s essay in this volume.

[63] For the most recent comprehensive publication on the chapel at Gernrode, see Hans-Joachim Krause, Gotthard Voss, and Rainer Kahsnitz, eds., Das heilige Grab in Gernrode: Bestandsdokumentation und Bestandsforschung, with Angelica Dülberg (Berlin: Deutscher Verlag für Kunstwissenschaft, 2007).

[64] Rainer Budde, Deutsche romanische Skulptur, 1050–1250 (Munich: Hirmer, 1979), 30–31, plate 29; and Kroesen, Sepulchrum Domini, 29, fig. 16.

[65] For a summary of the Externsteine site, see Gustaf Dalman, Das Grab Christi in Deutschland (Leipzig: Dieterich, 1922), 37–41. For the date of the carving, see Mechthild Schulze-Dörrlamm, ‘The Use of Caves for Religious Purposes in Early Medieval Germany (AD 500–1200)’, in Caves and Ritual in Medieval Europe, AD 500–1500, ed. Knut Andreas Bergsvik and Marion Dowd (Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2018), 228–29, with further references.

[66] Parker and Little, Cloisters Cross, 77.

[67] John Kinnamos [Ioannes Cinnamus], Epitome Rerum ab Ioanne et Alexio Comnenis gestarum, ed. Augustus Meineke, CSHB (Bonn: Weber, 1836), 277.7–278.5; John Kinnamos, Deeds of John and Manuel Comnenus, trans. Charles M. Brand (New York: Columbia University Press, 1976), 207–8; Niketas Choniates, Niketas Choniates, History, ed. Jan-Louis van Dieten, CFHB 3 (Berlin: De Gruyter, 1975), 222.76–86; Niketas Choniates, O City of Byzantium: Annals of Niketas Choniates, trans. Harry J. Magoulias (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1984), 125; and Iohannis Spatharakis, ‘The Influence of the Lithos in the Development of the Iconography of the Threnos’, in Byzantine East, Latin West: Art-Historical Studies in Honor of Kurt Weitzmann, ed. Doula Mouriki, Christopher Frederick Moss, and Katherine Kiefer (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University, 1995), 437–38.

[68] Spatharakis, ‘The Influence of the Lithos’, 438, fig. 6.

[69] No. 1962.27, Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland (twelfth century).

[70] See also manuscripts with similar iconography: cod. gr. 1156, fol. 194v, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vatican City; cod. 5, fol. 90v, Biblitoteca Palatina, Parma; and cod. Q908, fol. 85v, Institut Rukopisej, Georgian Academy of Sciences, Tbilisi, in Spatharakis, ‘The Influence of the Lithos,’ 437, 439, figs. 3–4; and Henry Maguire, ‘The Depiction of Sorrow in Middle Byzantine Art’, Dumbarton Oaks Papers 31 (1977): 144, 146. See also Kurt Weitzmann, ‘The Origin of the Threnos’, in De Artibus Opuscula XL: Essays in Honor of Erwin Panofsky, ed. Millard Meiss (New York: New York University Press, 1961), 486 and fig. 16.

[71] See, for instance, no. 43, Rosgarten-Museum, Constance. See also Adolph Goldschmidt and Kurt Weitzmann, Die byzantinischen Elfenbeinskulpturen des X.–XIII. Jahrhunderts, vol. 2 (Berlin: Deutscher Verlag für Kunstwissenschaft, 1930), no. 208, 75, plate 68 (dated to the eleventh century).

[72] Park, ‘The Wall Paintings’.

[73] A 1976 press release by the Metropolitan Museum of Art explains that Thomas Hoving thought the plaque had on its back an angel, the symbol of Matthew, and on its front the Harrowing of Hell. A $1000 reward was offered for finding the plaque. See ‘Search Instituted for Missing Section of Bury St. Edmunds Cross – Cross Now on View Again at the Cloisters’, press release, August 1976, Ivory Cross Notes, Archives, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. For a summary of the suggested iconography on the plaque, see Parker and Little, Cloisters Cross, 91–92.

[74] Cecily Hennessy, ‘Winchester’s Holy Sepulchre Chapel and Byzantium Iconographic Transregionalism?’, in The Regional and Transregional in Romanesque Europe, ed. John McNeill and Richard Plant (London: Routledge, 2021), 99.

[75] Ingeborg Psalter, Ms 9, fol. 28v, Musée Condé, Chantilly. See also Florens Deuchler, Der Ingeborgpsalter (Berlin: De Gruyter, 1967), 57–58, fig. 32.

[76] On the possible Danish connections with the Cross, see T. A. Heslop’s essay in this volume.

[77] On Henry the Lion’s visits to Jerusalem and Constantinople, see Hennessy, ‘Winchester’s Holy Sepulchre Chapel’, 99.

[78] On this, see Charles Little’s essay in this volume.

[79] Abbas Petroburgensis Benedictus, Gesta Regis Henrici Secundi Benedicti Abbatis. The Chronicle of the Reigns of Henry II. and Richard I. A.D. 1169–1192; Known Commonly under the Name of Benedict of Peterborough, ed. William Stubbs, vol. 1 (London: Longman, 1867), 346; and Ferenc Albin Gombos, ed., Catalogus fontium historiae Hungaricae, vol. 2, (Budapest: Szent István Akadémia, 1937), 1054, no. 2510. See also Ferenc Makk, The Árpáds and the Comneni: Political Relations between Hungary and Byzantium in the 12th Century (Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó, 1989), 120.

[80] Dezsö Dercsényi, Romanische Baukunst in Ungarn (Budapest: Kossuth, 1975), 197.

[81] On Henry II’s children, their spouses, and the cult of Becket, see Cecily Hennessy, ‘Thomas Becket, Henry II, Daughters and Sons: A Family Affair’, Journal of the British Archaeological Association 176 (2023): 71–95. On the ‘Channel Style’ and the Cross, see Ursula Nilgen, ‘Das große Walroßbeinkreuz in den “Cloisters”’, Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 48, no. 1 (1985): 39–64; and Neil Stratford, ‘The Cloisters Cross’, The Burlington Magazine 156, no. 1336 (2014): 464. See also Neil Stratford’s essay in this volume.

[82] Georg Swarzenski, ‘Aus Dem Kunstkreis Heinrichs der Löwen’, Städel-Jahrbuch 7/8 (1932): 241–397; and Neil Stratford, ‘Lower Saxony and England: An Old Chestnut Reviewed’, in Der Welfenschatz und sein Umkreis, ed. Joachim Ehlers and Dietrich Kötzsche (Mainz: P. von Zabern, 1998), 243–58, esp. 258; on Cologne merchants having their own Guildhall in London before 1170, see Stratford, 256.

[83] See, for instance, Parker and Little, Cloisters Cross, 218–22, in relation to Bury St Edmund’s. In relation to the Cham ridet couplet, see Sabrina Longland, ‘A Literary Aspect of the Bury St. Edmunds Cross’, Metropolitan Museum Journal 2 (1969): 45–74.

[84] Longland, ‘A Literary Aspect’, esp. 54. On the integration of learning among the Victorines through everyday interaction, and recent bibliography on the Victorines, see Joseph Hopper, ‘Intellectual Community in Saint Victor: 1108–c. 1200’, Historical Research 20 (2025): 1–15. See also Sabrina Harcourt-Smith’s essay in this volume.

[85] Parker and Little, Cloisters Cross, 218.

[86] Parker and Little, Cloisters Cross, 185–86, 285n57.

[87] Parker and Little, Cloisters Cross, 222–23. See also Gerhard Lutz, ‘The Canonisation of Bernward and Godehard: Hildesheim as a Cultural and Artistic Centre in the 12th and 13th Centuries’, in Romanesque Saints, Shrines and Pilgrimage, ed. John McNeill and Richard Plant (London: Routledge, 2020), 42.

[88] Lutz, ‘The Canonisation of Bernward and Godehard’, 44–47.

[89] Lutz, ‘The Canonisation of Bernward and Godehard’, 42–43, fig. 4.1.

[90] Lutz, ‘The Canonisation of Bernward and Godehard’, 42–43.

[91] On Adelog’s tombstone, see Lutz, ‘The Canonisation of Bernward and Godehard’, 52n36.

[92] This is summarised in Gardner’s handwritten paper given at the Frick, April 1973, p. 20, William Stephen Gardner Papers, Cloisters Library and Archives, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.