Sabrina Harcourt-Smith

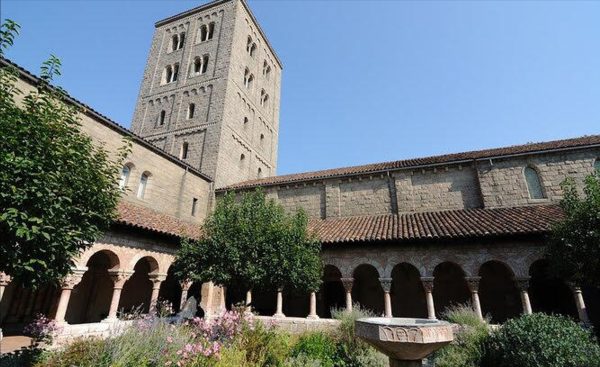

On a Monday morning in early May 1964, I turned up for work at the Medieval Department of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Thomas Hoving, then associate curator, drove me uptown to the Cloisters in Fort Tryon Park (Fig. 4.1a–b). Without delay, he installed me at the top of the tower at a table with the Cloisters Cross in pieces before me and disappeared. Within minutes, a clap of thunder shook the tower, the heavens opened, and lightning rent the skies. A dramatically cataclysmic thunderstorm raged around us—a sound-and-effects team could not have bettered it. Tom, always a cheerful soul, put his head round the door, laughed and said, ‘Are you alright? This is terra tremit [the earth trembles] . . . come to visit us’.

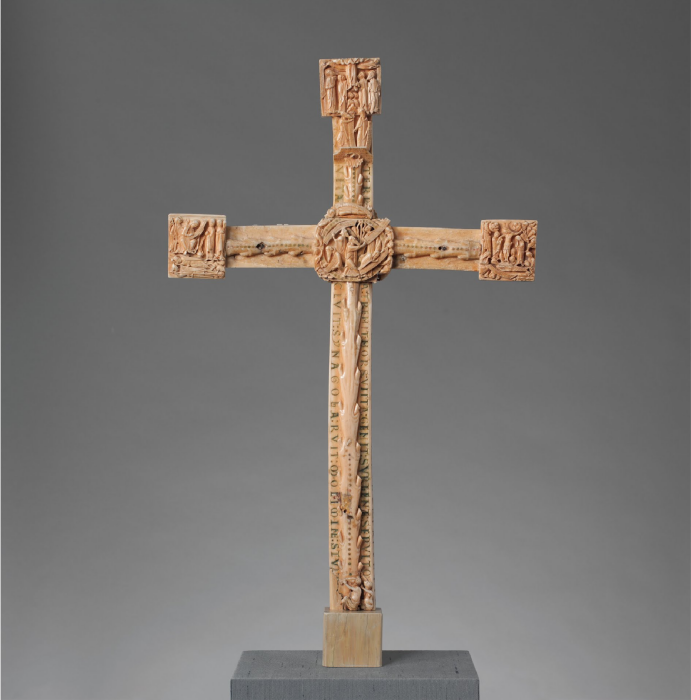

In June 1964, Hoving’s article in The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, hot off the press, threw open an array of mysteries and questions surrounding the Cross and offered many paths to go down.1 This essay seeks to highlight a singular aspect of the Cross: its didactic role in a preaching context. Within this context, reflections on a possible milieu for its inspiration will be suggested. Certainly, the Cross can be seen and read as a sermon of scriptural typology, embellished by its figures. It could have been used for display and discussion, both for the laity and within monastic and scholarly circles. It may also have served as a sort of ‘travelling sermon’.

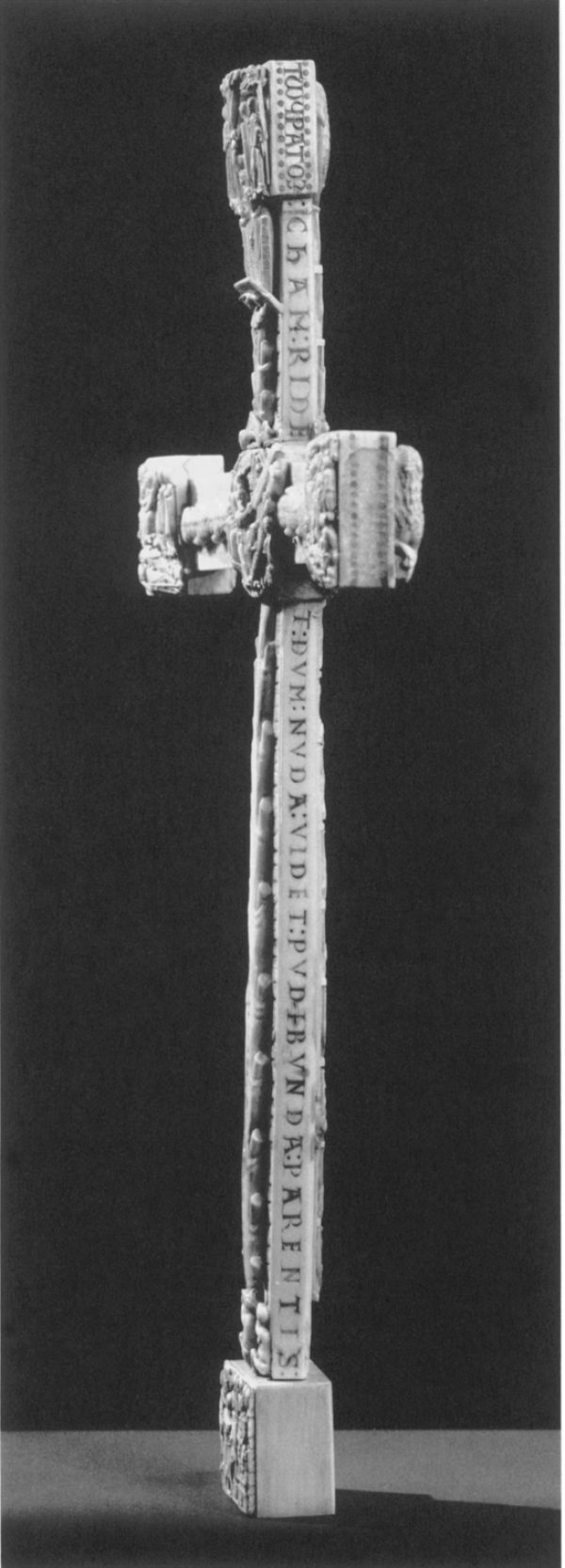

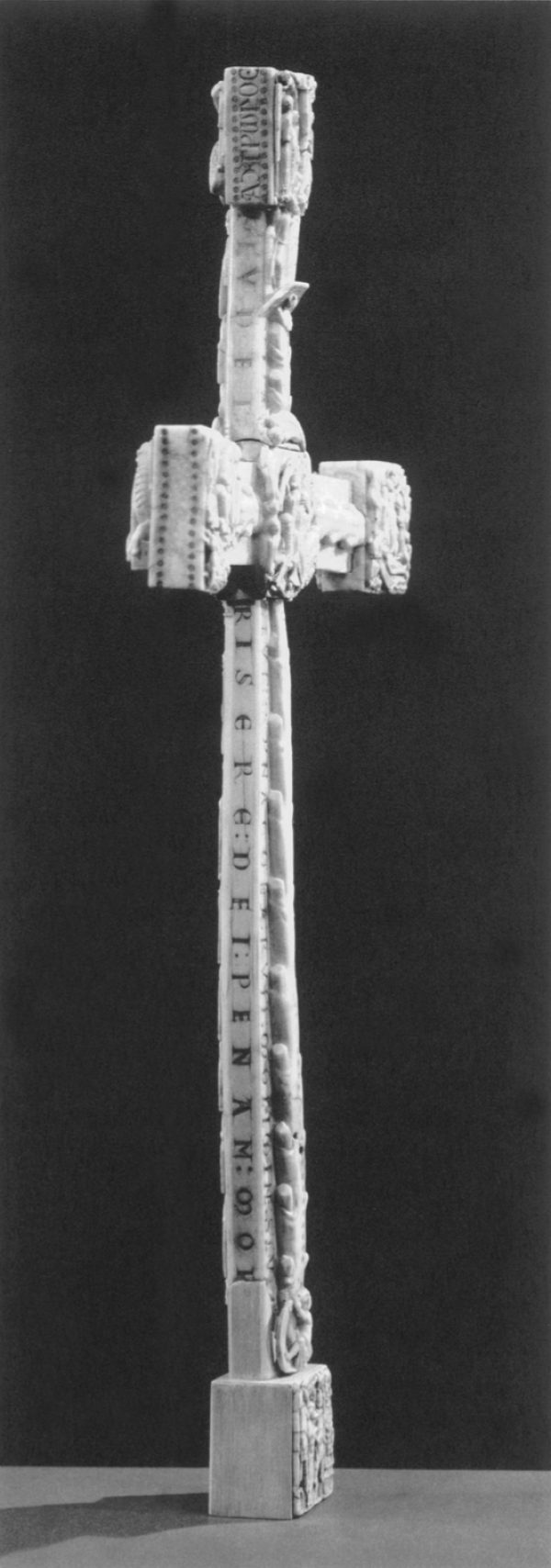

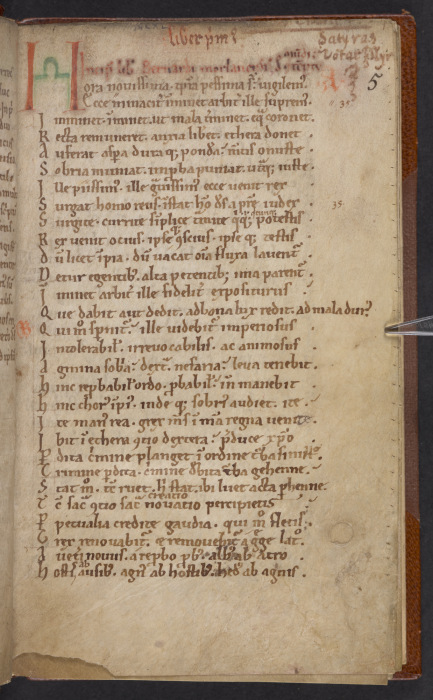

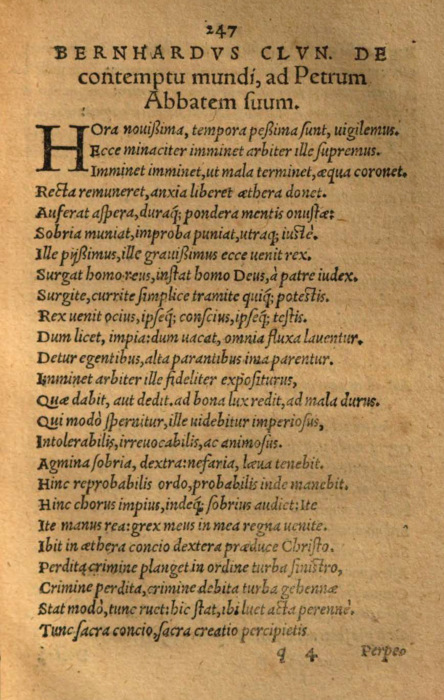

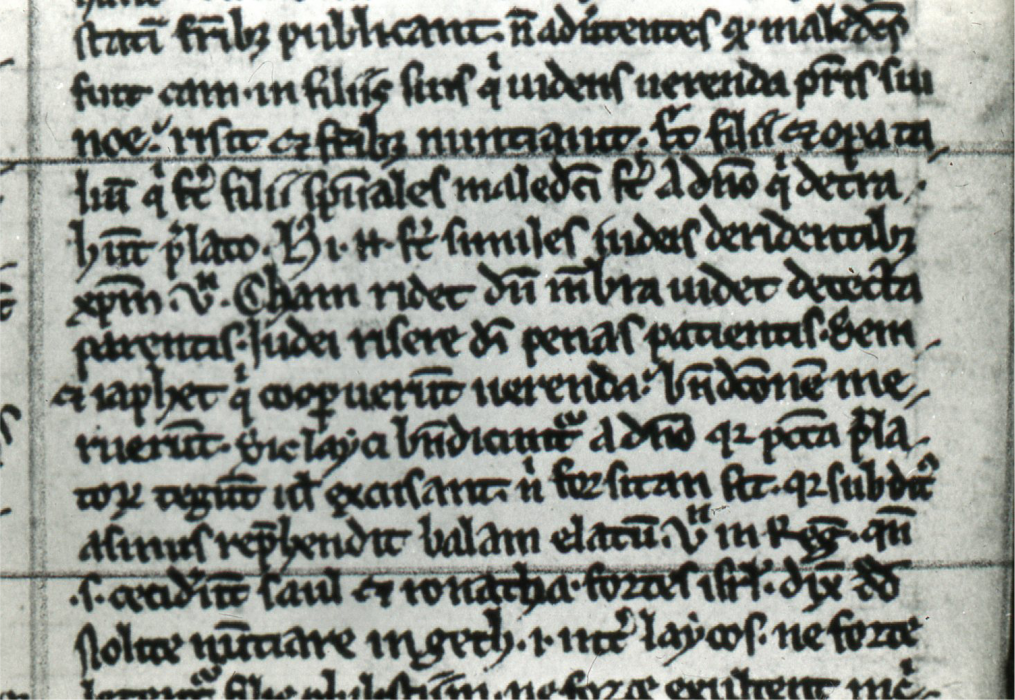

A clue to the preaching aspect of the Cross lies with the two rhyming hexameter couplets that are so elegantly and prominently inscribed in majuscules down its front and sides (Figs. 4.2–4.4). On the front is the verse ‘TERRA TREMIT MORS VICTA GEMIT SURGENTE SEPULTO. VITA CLUIT SYNAGOGA RUIT MOLIMINE STULT[O]’ (The earth trembles, Death defeated groans with the buried one rising. Life has been called, Synagoga has collapsed with great foolish effort). On the sides is the verse ‘CHAM RIDET DUM NUDA VIDET PUDIBUNDA PARENTIS. IUDEI RISERE DEI PENAM MOR[IENTIS]’ (Cham laughs when he sees the naked private parts of his parent. The Jews laughed at the pain of God dying). The late Christopher Hohler pointed out to me that the distinctive and unusual metre of these verses is the same as that used by the Cluniac monk, Bernard of Morlas or Morlais/Morlaix (Bernard of Cluny), in his long, satirical, and moralising poem De Contemptu Mundi, dedicated to Peter the Venerable and written probably about 1144 (Fig. 4.5).2 Peter the Venerable also composed with this metre in his Rhythmus in laude Salvatoris. Both the Cross and Bernard’s verses are written in rhyming couplets of dactylic hexameters with two-syllable end rhymes, used in Greek and Latin poetry.

In his prologue, Bernard says that he composed in verse because it would appeal to people more than prose and that rhymes are easier to remember and thus to learn from. He also refers to his achievement in having written such a lengthy poem (three thousand verses) in such a difficult metre. He adds that he could not have done it without divine inspiration.3 André Cresson throws much light on this poetic monk. Cresson expounds on the heroic, difficult ‘versification’, disclosing at least fifteen extant manuscripts in present-day libraries which include those in Paris, Toulouse, Douai, and Saint-Omer.4 It is clear from sources that Bernard’s unusual rhyme scheme and metre attracted interest and approval from his own time through later centuries. Because De Contemptu Mundi censors the corruption of monasteries, popes, and clergy, it became popular with hard-line reformers in the sixteenth century, in particular Lutheran theologian Matthias Flacius (1520–1575), who edited it in 1556 (Fig. 4.6).5 The opening stanzas, starting with ‘Ora novissima, tempora pessima sunt vigilemus’, were famously translated and adapted by Victorian hymn-writer the Reverend J. M. Neale as ‘The world is very evil the times are getting late’.6 Another Victorian who praised Bernard’s lyrics was American hymn-writer Samuel W. Duffield.7

Hohler emphasised to me that this particular style of writing poetry with moralising content belonged very much in the mid-twelfth century. Other significant users of this poetic construction were Marbod of Rennes (1035–1123) and Hildebert of Lavardin (1066–1133). Marbod used it in his poem Stella maris, quae sola paris. Hildebert was bishop of Le Mans in 1096/97, then archbishop of Tours until his death in 1133. In his Prologue, Bernard of Cluny praised Hildebert for being one of the few remarkable users of this rhythm.8

The selection of the two couplets as prominent statements on the front and sides of the Cross will surely have been made for in-depth reasons and with scholarly planning. A search for the sources of such verses lies always with their use. The source of the terra tremit verse presents possibilities and queries. Suger, abbot of Saint-Denis from 1122 until his death in 1151, had constructed a Great Cross, which he describes, and relates how it was made:

Therefore we searched around everywhere by ourselves and by our agents for an abundance of precious pearls and gems, preparing as precious a supply of gold and gems for so important an embellishment as we could find, and convoked the most experienced artists from divers parts. They would with diligent and patient labour glorify the venerable cross on its reverse side by the admirable beauty of these gems; and in its front—that is to say in the sight of the sacrificing priest—they would show the adorable image of Our Lord the Saviour, suffering, as it were, even now in remembrance of His Passion.9

This cross disappeared, but the pedestal was copied on a smaller scale on the pedestal of a cross originally in Saint-Bertin, now in the museum of Saint-Omer.10 On the capital, two of the figures were Terra and Mare. Suger’s distich reads, ‘Terra tremit, pelagus stupet, alta vacillat abyssus; Jure dolent domini territa morte sui’ (The earth trembles, the sea is stunned, the deep abyss sways; Rightly terrified by the death of its Lord).11 Erwin Panofsky pointed out that Suger’s verse was patterned on Genesis 1:2: ‘Terra autem erat inanis et vacua, et Tenebrae erat super faciem abyssi, et spiritus dei ferebatur super aquas’ (And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters).12 David, author of the Psalms, holds a scroll with the words terra tremuit (trembled) on the Klosterneuburg ambo of 1181, adjacent to a scene of the Harrowing of Hell (Psalm 75[76]:9).13 This clearly links the earth shaking with liberating the souls of the dead from limbo and is appropriate to the images of Adam and Eve brought back to life at the foot of the Cloisters Cross.14

The acerbic Cham ridet couplet was in use in a moralising context in mid-to-late twelfth-century biblical studies in the Paris schools. Moral or allegorical interpretations of the story in Genesis 9:20–27 of Noah’s drunken behaviour and his son Cham’s derision can be found in early church writers such as Isidore of Seville, Rabanus Maurus and, notably, in mid-twelfth-century biblical writings from the Abbey of Saint-Victor in Paris. Richard of Saint-Victor, who died in 1173, devoted a whole chapter to it in his Allegoriae. He writes, ‘Noah signifies the prelates . . . who . . . when they are full of human weakness . . . Cham laughs at the shame [and signifies] the sinners (reprobi)’.15

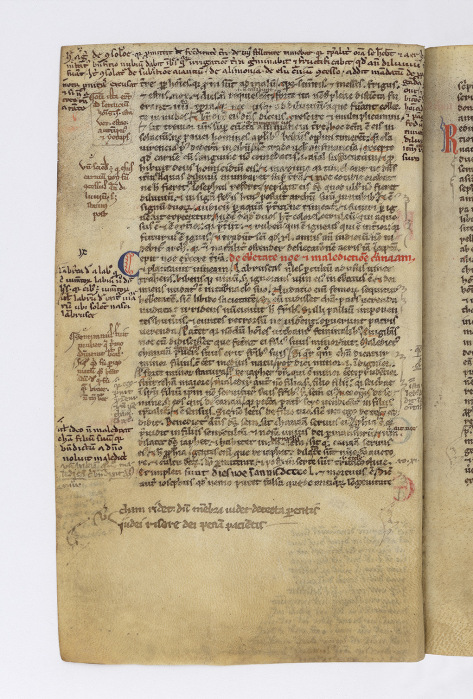

Peter Comestor’s Historia Scholastica, sometimes called The Histories, was a sort of historical narrative of the Bible, and it rapidly became a prescribed text for theology students. A late twelfth-century copy has a marginal annotation to the text of Genesis with a gentler version of the Cham ridet couplet, using detecta (revealed) instead of nuda (naked flesh), membra (limb/genital member) instead of pudibunda (shame), and patientis (suffering) instead of morientis (dying) (Fig. 4.7).16 Comestor was an active, indeed pivotal, biblical scholar in Paris, having arrived there possibly in 1164. He became chancellor of Notre Dame from sometime between 1164 and 1168, holding that position until 1178 or 1180. He probably completed the Historia Scholastica between 1169 and 1173. It became a standard textbook of scholastic theology and was copied and sometimes annotated. After he left his post at Notre Dame, Comestor is thought to have retired to the Abbey of Saint-Victor, where he was buried. As chancellor he made a significant contribution to the emerging University of Paris as it evolved from its beginnings as the Cathedral School of Notre Dame.

In northern France other variants of the Cham ridet couplet can be found. One is part of a large collection of verse compiled in the late thirteenth century in a volume from Reims Cathedral.17 This is the only example, so far discovered, where the wording is exactly the same as that found on the Cross. The Cham ridet couplet is also found in a late twelfth-/early thirteenth-century collection of anonymous verses from the Abbey of Notre-Dame at Lyre, Normandy.18 This example of the couplet has the milder words of membra and detecta but ends with the more severe morientis, as on the Cloisters Cross.

Past research by Elizabeth Parker discovered that a version of the verse can be found in copies of the Glossa ordinaria.19 The Glossa can be described as a vast reference book, as it were, of the Bible, which emerged in the late 1130s or the 1140s, possibly originating from the circle of Anselm of Laon. The earliest known example of a compete twelfth-century Glossa is a six-volume set of the 1130s or 1140s that came from a library in Germany.20

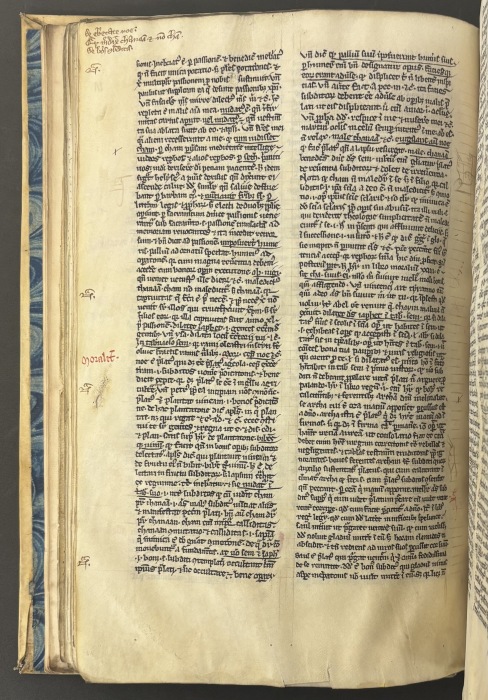

Another interesting user of the verse was Stephen Langton, archbishop of Canterbury from 1207 and a well-known preacher and scholar as well as a diplomatic negotiator with King John over the Magna Carta. He studied in Paris from circa 1170, was made a Master of Theology and the Liberal Arts within the next few years, and was soon teaching at the newly blossoming University of Paris. Langton produced his Commentary on the Histories before 1176. It is no surprise to find that in his Postillae super Genesim, a commentary on Genesis, he uses a version of the Cham ridet verse in an allegorical exposition of the Noah and Cham story from Genesis 9. The moralising allegory is similar in content to Richard of Saint-Victor’s Allegoriae mentioned above. One manuscript of the Postillae was copied in the early thirteenth century, probably in England, and is in the British Library, but other copies exist in European libraries (Fig. 4.8).21 Langton wrote it in Paris, probably around or after 1180, by which time he had become a Master of Theology. Contemporary sources tell us that Langton was a popular and prolific preacher during his thirty or more years in Paris (ca. 1170 to shortly after 1200). In May 1207, Pope Innocent III wrote to King John attesting Langton’s renown as a doctor in theology and the liberal arts.22 The body of extant manuscripts of his sermons and exegetical works is enormous.

Modern research by scholars has unravelled the intricate influences between the works of Langton, Comestor, Peter Lombard, and Peter the Chanter—in other words, the top biblical scholars of the day in Paris.23 Mention should be made here also of the works of the English writer Odo of Cheriton (ca. 1185–1247), who also knew and used a version of the couplet. His writings are notable for his satirical sermons, often with allegories, fables and exempla. He turns the whole Noah story into a moralising admonition about lapsed prelates, with the Cham couplet as a sort of colourful proverb (Fig. 4.9).24 His habit of using the ‘allegory’ and the ‘moral’ stemmed straight from Langton, whose pupil he was in Paris before Langton left in 1206. Odo’s use of the couplet in his popular Sunday Sermons represents a preaching aspect of the Cloisters Cross. Odo’s works were too late for any connection with the Cross; however, their documented role as preaching guidance for clergy from around the second decade of the thirteenth century gives an idea of how such didactic writings were of value to clergy and, as Albert Friend phrased it, ‘clearly designed to serve as models for preachers’, with Odo’s Summa ‘intended as a simple guide or handbook for priests’.25

During the second half of the twelfth century, the scholastic influence of the Abbey of Saint-Victor waned. Beryl Smalley, in her seminal volume The Study of the Bible in the Middle Ages, writes how the three Paris ‘Masters of the Sacred Page’ made themselves responsible for continuing the Victorine tradition: Comestor, Peter the Chanter, and Langton.26 These three masters of overlapping generations had ‘a common interest in biblical studies and in practical moral questions’.27 In their hands lectio divina changed into the academic lecture course. Smalley writes of ‘the inquisitive energy which abounded at Paris in those years’.28

Langton was undoubtedly the most influential theology teacher of his time in Paris, even though the concept of ‘theology’ as a subject was only slowly emerging. The schools (scola) of the last quarter of the twelfth century were slowly being transformed from their association with institutions such as the cathedral of Notre Dame and the Abbey of Saint-Victor and from being cathedral-run into a university. Langton’s classes would have been small, but nonetheless a vibrant and thriving milieu for biblical exchanges and discussions. His sermons and lectures are full of biblical quotations, allegories, and moralising exempla. A man of his intellect and stature is a key figure in the intriguing puzzle of tracing elusive texts. He would have been a channel through whom ideas, knowledge and unusual texts spread within and beyond his own sphere.

Christopher de Hamel has studied the new types of books that were emerging in scholarly circles, especially Paris, from around 1180 through the next four decades. The gradual change was from monastic, church-based writings to books of information such as encyclopaedias, anthologies, collections of literary extracts including verse, and miscellanies.29 The circle of Langton and his colleagues was undoubtedly the kind of forum where such new books would have been acquired for perusal and study. Verse collections were popular. In his Verses in Sermons, Siegfried Wenzel highlights the trend in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries for setting doctrine into poetry.30 The Cham ridet couplet appears in twelfth- and thirteenth-century anthologies, but in the Paris-inspired Comestor and Langton texts it is singled out for use in a preaching context.

Undoubtedly other examples of the Cham ridet couplet, complete or only one line, can be found in Genesis commentaries and in verse collections, from about 1160 through the thirteenth century. Its use in writings by Comestor and Langton is evidence enough that it was already in circulation by the 1170s. Details regarding the different variants of the inscription have been published elsewhere.31

The harsh wording of nuda, pudibunda and morientis found on the Cross and in the manuscript in Reims Cathedral was subsequently altered to the gentler version. It is not impossible that Langton himself altered the wording in the early 1200s. Deus moriens, the concept of God actually dying, would certainly have been considered heretical. Deus patiens, the suffering God, was a more fitting choice and probably the original.

This essay suggests that whoever chose the moralising verses for the front and sides of the Cloisters Cross was likely to have been someone able to draw not only on the resources of their own (possibly monastic) library but also on the inspiration of the new books of the Paris schools in the scholarly metropolis of Northern Europe.32 There, no doubt, the Cham ridet couplet would have been found to be adjusted and reworded for use on the Cloisters Cross. The opening words of the terra tremit verse could be found, written on a Great Cross at nearby Saint-Denis. Was this the stimulus for a new composition, following the structure of Cham ridet? Unless it can be found somewhere else, the possibility must be that it was devised specifically for the Cloisters Cross, with all that implies about the origin, function, patronage, and interpretation of that remarkable object.

Citations

[1] Thomas P. Hoving and James J. Rorimer, ‘The Bury St. Edmunds Cross’, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 22, no. 10 (1964): 317–40.

[2] Bernard of Morlais, Liber 1, De Contemptu Mundi, twelfth century, MS Cotton Cleopatra A.VIII.2.2, British Library, London; and Bernard le Clunisien, Une vision du monde vers 1144: Texte latin, introduction, traduction et notes, ed. André Cresson (Turnhout: Brepols, 2009). I am grateful to Neil Stratford for this reference.

[3] Bernard le Clunisien, Une vision, 73–74.

[4] Bernard le Clunisien, Une vision, 73.

[5] Bernard de Morlaix, The Rhythm of Bernard de Morlaix, Monk of Cluny, on the Celestial Country, 7th ed., ed. and trans. J. M. Neale (London: J. T. Hayes, 1866), 5. Successive reprints include editions in 1597, 1610, 1626, 1640, and 1820.

[6] Bernard de Morlaix, The Rhythm, 13.

[7] Bernard de Morlaix, The Heavenly Land from the De Contemptu mundi of Bernard de Morlaix Monk of Cluny (XII. Century), trans. Samuel W. Duffield (New York: Randolph, 1867), vii–x, xv.

[8] Bernard le Clunisien, Une vision, 73–74.

[9] Sugerius Sancti Dionysii Abbas, Liber de rebus in administratione sua gestis, chap. XXXII, De crucifixo aureo, in Patrologia Latina, ed. Jacques-Paul Migne, vol. 186 (Paris, 1854), 1231–40; and Suger, Abbot of St.-Denis, Abbot Suger on the Abbey Church of St.-Denis and Its Art Treasures, ed., trans., and annot. Erwin Panofsky (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1946), 56–59.

[10] Suger, Abbot Suger, fig. 11.

[11] Translation with the author by Chris Whittick. Panofsky notes that abyssus is the Latin equivalent of ‘the deep’ in the King James Bible; Suger, Abbot Suger, 177. See also Philippe Verdier, ‘La grande croix de l’abbé Suger à Saint-Denis’, Cahiers de civilisation médiévale 13 (1970): 17; and Jacques Doublet, Histoire de l’abbaye de S. Denys en France (Paris: Nicolas Buon, 1628), 253.

[12] Suger, Abbot Suger, 177.

[13] Also see Cecily Hennessy’s essay in this volume.

[14] Elizabeth C. Parker and Charles T. Little, The Cloisters Cross: Its Art and Meaning (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1994), 97.

[15] Palémon Glorieux, Répertoire des maitres en théologie de Paris au XIIIe siècle, vol. 1 (Paris: Vrin, 1933), no. 104; author’s translation.

[16] Peter Comestor, Historia Scholastica, late twelfth century, Vat. lat. 1973, fol. 14v, Biblioteca Apostolica, Vatican, Vatican City.

[17] Collection of vitae, sermons, and verses, late thirteenth century, MS. 1275, fol. 188v, Bibliothèque Municipale, Reims; and Sabrina Longland, ‘A Literary Aspect of the Bury St. Edmunds Cross’, Metropolitan Museum Journal 2 (1969), 63, fig 10.

[18] Collection of verses, largely sermons, late twelfth century, MS. A. 452, fol. 452v, Bibliothèque Municipale, Rouen; and Longland, ‘A Literary Aspect’, 61–63, fig. 9.

[19] Parker and Little, Cloisters Cross.

[20] Christopher de Hamel, Glossed Books of the Bible and the Origins of the Paris Booktrade. (Woodbridge: Brewer, 1984).

[21] Stephen Langton, Postillae super Genesim, thirteenth century, Royal MS. 2. E. XII, fol. 25v, British Library, London.

[22] Innocent III, Selected Letters of Pope Innocent III Concerning England (1198–1216), ed. C. R. Cheney and W. H. Semple, Nelson’s Medieval Texts (London: Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1953), 87; and Longland, ‘A Literary Aspect,’ 72.

[23] See, for instance, Mark J. Clark, ‘Peter Lombard, Stephen Langton, and the School of Paris: The Making of the Twelfth-Century Scholastic Biblical Tradition’, Traditio 72 (2017): 171–274; Ian P. Wei, Intellectual Culture in Medieval Paris: Theologians and the University, c. 1100–1330 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012); and John W. Baldwin, Masters, Princes, and Merchants: The Social Views of Peter the Chanter and His Circle (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1970).

[24] Odo of Cheriton, Sermones Dominicales, thirteenth century, Cod. lat. 0. II. 7, fol. 36v, Real biblioteca del Monasterio de San Lorenzo de El Escorial, Madrid.

[25] Albert C. Friend, ‘Master Odo of Cheriton’, Speculum 23, no. 4 (1948): 641, 657.

[26] Beryl Smalley, The Study of the Bible in the Middle Ages, 3rd ed. (Oxford: Blackwell, 1983), 196.

[27] Smalley, Study of the Bible, 197.

[28] Smalley, Study of the Bible, 196.

[29] Christopher De Hamel, Meetings with Remarkable Manuscripts (London: Allen Lane, 2016), 371.

[30] Siegfried Wenzel, Verses in Sermons: ‘Fasciculus morum’ and Its Middle English Poems (Cambridge, MA: Mediaeval Academy of America, 1978).

[31] Longland, ‘A Literary Aspect’.

[32] See, for instance, Richard W. Southern, The Making of the Middle Ages (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1953), 199.