Neil Stratford

In May 1961 the keeper of British and Medieval Antiquities at the British Museum, Rupert Bruce-Mitford, was in his mid-forties and had been keeper for seven years (Fig. 3.1).1 He was a passionate archaeological researcher, chiefly renowned for his work on the Sutton Hoo Ship Burial. He was a man of enormous tenacity and charm; I knew him well and we became friends. One day he drove me like a dervish in a small, turquoise-blue car to Sutton Hoo, where we visited the mounds and had tea with Mrs Pretty, the sister-in-law of the deceased donor, also Mrs Pretty, who had been told to give the finds to the nation in a séance by her dead husband. We overlapped by two years, after I was appointed in 1975 to succeed him, and he was a role model of correct behaviour, never interfering—he had been made a research keeper directing a team charged with the publication of Sutton Hoo. He died prematurely in 1980. He is one of the principal actors in the story I am going to tell.

The other actor is Ante Topić Mimara (hereafter Topić, as he was generally known) (Fig. 3.2). Croatian by birth, his true name is in doubt as is his date of birth. By 1961 he was probably over sixty years of age. His career can scarcely be reconstructed, as so many different claims and lies and half-truths have been thrown into the pot, not all by himself. For instance, the claim that he was a Yugoslav spy seems fragile, or that in Berlin during the war he was a close friend of Hermann Goering.2 But that he was in Munich in the American zone in 1948, at the Central Collecting Point for the return of works of art stolen by the Nazis, is indisputable. He was supposedly, and perhaps genuinely, representing the Yugoslav government. He oversaw the shipment of a very large number of paintings and objets d’art to Yugoslavia, many of which have never resurfaced and anyway had not come from Yugoslavia. He had charm and he was plausible. He was clearly a man beyond the comprehension of a Bruce-Mitford, and of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, I suspect.

Topić paid a preliminary visit to the British Museum in December 1960, when he showed closely guarded photographs of an ivory cross (now the Cloisters Cross) to Peter Lasko, who was an assistant keeper there and who from the beginning advised Bruce-Mitford on the Cross. On May 18, 1961, Topić visited Bruce-Mitford at the British Museum. He again showed photographs of the Cross; the object itself he kept deposited in a bank vault in Zurich. He offered to sell the Cross to the museum’s trustees for £200,000, a vast sum at the time. When Sir Frank Francis, the director and principal librarian of the museum, replied to Bruce-Mitford’s memorandum about the visit, he pointed out that a special grant from Parliament would be necessary to purchase the Cross, and that to make such a request, ‘full details of the pedigree’ of the Cross must be given as well as ‘convincing evidence of its importance as an English work of art’. Thus, from the start, the question of the Cross’ provenance, which was to remain an insurmountable obstacle to its purchase, was raised and would never go away.

Curiously enough, the ‘Englishness’ of the Cross (if I can call it that) was never seriously put in doubt during the negotiations, either in England or in America. We learn from these early exchanges in the museum that the Cross ‘had been inspected in Zurich by Mr Pope-Hennessy of the Victoria and Albert Museum some time ago’. It is also stated that the Cleveland Museum of Art ‘had offered $500,000’ for the Cross, though this sounds like a very vague rumour.3 Cleveland, through its medievalist William Milliken, had bought the Guelph Treasure in 1930, and Milliken was still very active even after his retirement from the directorship of the museum in 1958. I think he would have pursued the Cross if it had been offered. The other factor in Francis’s memorandum is the necessity for the Cross itself to be inspected. No photographs were left at the museum at this stage. Why? Because Topić’s wife, the much younger Wiltrud Mersmann, an art historian from Bavaria who had been with Topić at the Munich Central Collecting Point, was writing a book on the Cross; the images were under her thumb until the book was published. The book, never finished, was due out at the end of 1961. She came to London in July of that year and met everybody at the museum. There is a letter of thanks from Lasko to Topić’s wife in which Lasko suggests that the Cross is not of the Anglo-Saxon date which she is proposing but rather is post-Conquest. Lasko was to become a central figure in the pursuit of the Cross. In Figure 3.3 he can be seen at a border post near Maastricht, seated in front of the car. With him on the left are George Zarnecki and C. R. (Reg) Dodwell. I am inclined to think that the photograph was taken at the Dutch-German border post when they were on their way to the great Charlemagne exhibition of 1965 in Aachen. Zarnecki was among the key authorities who supported Bruce-Mitford’s campaign for the Cross.

In January 1962, Bruce-Mitford and Lasko made a second trip to Zurich and the bank vault; they had made a preliminary visit in June 1961. The delay is understandable. I will not describe the protocols which had to be surmounted for a servant of the Trustees of the British Museum to undertake such a journey, spending public money, for heavens’ sake. In July 1962 when Bruce-Mitford finally made a submission to the trustees for the purchase of the Cross, he says: ‘The cross is said by the owner to have come from a Balkan monastery’. He adds: ‘The cross is regarded by all experts who have so far seen it, including Professor Francis Wormald and Dr George Zarnecki, as certainly English, and the most likely date would be from the late 11th century to about 1120’. The initiative to buy the Cross was received by the trustees with enthusiasm. Notwithstanding any reservations that may have been expressed at their meeting, general support for its purchase was apparently unanimous, and by the autumn Bruce-Mitford had begun to try to raise the money from H.M. Treasury. Without following all the details of the bid, it is enough to say that he succeeded, with the written help of many others; but the promise of the money was always on certain conditions having to do with the legal title to ownership of the Cross and its provenance. Who was the person who had sold Topić the Cross?

Bentley Bridgewater, the museum’s secretary and a man of considerable influence, intervened and negotiated with the Treasury, but always the same conditions of the title and provenance of the Cross were specified. And so things dragged on, with Topić adamant. It may be asked why Topić was so patient in all this, given that the Metropolitan Museum of Art was clearly interested too. I think it was due to his wife’s pressure. She believed passionately, as she worked on what was to become her article in the Wallraf-Richartz Jahrbuch, that the Cross was a great English work of art and that its proper place was in the British Museum.4 This was a view tenaciously held throughout by both Mersmann and Topić. It was the source of their ultimate disillusion with the museum and their long-held reluctance to sell the Cross elsewhere. As I have said, there was one overriding obstacle to the Cross’ purchase: its total lack of provenance and title. It must be remembered that 1961 was only sixteen years after the end of the Second World War. In 1963, Topić actually said that he had had the Cross for fifteen years, a span of time that would get us to 1948 and the Munich Central Collecting Point. Among other things which he let drop at times were that he had bought it from an elderly dealer whom he knew well and that it was from ‘Eastern Europe’. It is clear from a remark of the great art historian who worked under Adolph Goldschmidt, Hermann Schnitzler of Cologne, that he had been shown one of the five pieces which make up the Cross, a remark partially confirmed by a letter from the art historian Florentine Mütherich in the British Museum Archives.5 She was approached by Bruce-Mitford because Derek Turner in the Department of Manuscripts in the British Museum had heard that she knew of the Cross. She replied that she only knew of its existence secondhand, from Schnitzler who had seen one part of it.

Topić tells us that the Cross was covered in soot and grime when he first acquired it, and that he spent a lot of money having it cleaned, restored, and put together. As mentioned, in 1948 he was at the Munich Central Collecting Point, where objects of Nazi provenance were the daily bread for redistribution.

Lasko was always very bitter about the Treasury’s refusal to buy the Cross without its provenance and legal assurances of its ownership. In a memorandum from Bruce-Mitford to Bridgewater, after the Metropolitan Museum of Art had bought the Cross, Bruce-Mitford casts aspersions on the Met and its director, James Rorimer, who had himself been at the checkpoint in Munich as an American member of the Allied Forces’ Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives unit at the end of the war. He writes: ‘I do not believe that the Met are worried over the legal or political aspects of the purchase’.6 That was certainly true. It was also ‘sour grapes’; what should we think?

We are now more than fifty years after the date of purchase of the Cross. Even so, I would not be totally surprised if the Cross does turn out to be a time bomb. Speaking personally, I have a lot of sympathy for Sir Ronald Harris at the Treasury and the Paymaster General at the time, John Boyd-Carpenter, when they finally withdrew their offer of the grant to purchase the Cross in early 1963. The British Museum Archives contain Bruce-Mitford’s graphic account of the final meeting with Topić and the Americans in Zurich:

We found that Rorimer’s brightest young man [this is Thomas Hoving—the first time he appears in the museum’s files], had arrived in Zurich just before us with an offer to purchase not only the cross but four other pieces in the collection for $900,000. The money had been transferred to a Zurich bank and was there ready for instant collection. Only his word to me stood between Mr Topić Mimara and the collection of the cash. The atmosphere was electric. After we all had met at dinner and walked back to the hotel where we and Topić were staying, the American asked Topić to go on for a little shot in his hotel. We stayed up, drinking coffee, till he came back. He said that Hoving had told him that next year he had said that he was to be the head of the Cloisters and could then have a purchase fund of $600,000 at his disposal and would undertake to purchase further items from Topić in the following year.

So that was that. So many people were involved in this two-and-a-half-year saga, thanks largely to Bruce-Mitford’s absolute refusal to give up. The committee formed by Bruce-Mitford comprised the great and good supporting his efforts: Thomas Boase and Zarnecki but also Otto Pächt, Francis Wormald, Julian Brown, Turner, and Lasko, of course.7 Many letters of support were received, including, for instance, from Dame Joan Evans, at that time president of the Society of Antiquaries. Here, too, is an extract of a letter from Sir Kenneth Clark: ‘It is indeed a most marvellous object and the kind of thing I like best in the world’. And Dom David Knowles, the great historian of Christian monasticism, based at Peterhouse, Cambridge, wrote: ‘The cross is a most magnificent and breath-taking work and it is a matter for congratulation that you and others should have decided to make every effort to secure it for the nation. To my mind, the art of the early twelfth century is absolutely—not only on account of its historical or antiquarian value—one of the greatest aesthetic achievements of north-western Europe. Personally, it moves me more than the mature Gothic art of the thirteenth century’.

As to the provenance of the Cross, perhaps we will never know. Topić absolutely refused to name it or the vendor from whom he claimed to have bought the Cross. He died in 1987 after the opening of the museum housing his collection in Zagreb. I was visited by the curator of that museum and shown photographs of many of the pieces to be exhibited. It was embarrassing: a poor assemblage. But earlier in 1982, with the encouragement of my friend Hanns Swarzenski, who knew him, I wrote Topić a letter, very official, in one last attempt to persuade him to divulge the provenance of the Cross, undertaking that the British Museum would keep his letter under seal until his death or until any date he specified. His reply was bitter but polite: ‘I cannot help you at this time since the man who sold the object to me is younger [sic] than me and still alive, and I also gave him my word that I will never disclose the information concerning the person who sold the object to me’.

As to Hoving’s part in all this, it is difficult to sort out truth from semi-truths and pure fiction. I have not seen the Met’s files, but if Rorimer’s preface to Hoving’s first article on the Cross is accurate, the Met was first aware of the existence of the Cross in 1956, and in 1959 Hoving and Carmen Gómez-Moreno saw the Cross in Zurich. However, Hoving’s name does not appear in the British Museum Archives until 1963. Indeed, if Hoving was already involved in 1959, he was not effective. For, nearly two years later, Topić was offering the Cross to the British Museum. Yes, in 1963 he was there to clinch the deal (he called it ‘my cross’), but he was only able to do so because the Treasury refused to acquire a highly suspicious object. Credit to Hoving for the purchase must therefore be relative. He was, of course, responsible for the subsequent noise about Bury St Edmunds and Master Hugo, Abbot Samson, and the anti-Jewish theory. But to quote Marlowe: ‘But that was in another country and besides the wench is dead’.8

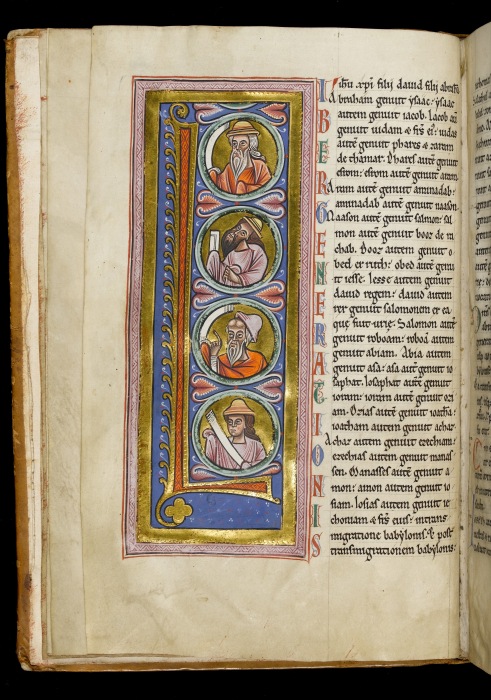

If I am allowed a postscript, I published in July 2014 a letter in Burlington Magazine, which, like all such letters, seems to have attracted little or no notice.9 My letter was accompanied by the single figured initial in the gospel book from the Abbey of Le Parc at Louvain, now in the Fitzwilliam Museum at Cambridge (Fig. 3.4). I hope that the image speaks for itself. It is ‘Channel School’, and I also referred in my letter to the admirable article of 1985 by Ursula Nilgen, who held a similar opinion.10 Her article seems to get lost from many of the bibliographies on the Cross.

Citations

[1] This essay appears here, with minor revisions, as it was delivered to the conference Revisiting the Cloisters Cross: A One-Day Colloquium, held at the Courtauld Institute of Art in London on 12 May 2023. The notes were added by the editors of this volume. All the correspondence cited in this essay is found in the British Museum Archives under the misleading rubric ‘Bury St Edmunds Ivory Altar Cross’ (Offered by Ante Topic Mimara), in three box files labelled Correspondence 1960–Jan. 1963; Correspondence Feb. 1963–; and 45/51/114 (a Secretariat file), BEP, Potential Purchases, British Museum Archives, London.

[2] For some background on this, see Konstantin Akinsha, ‘News Reports: Ante Topic Mimara, “The Master Swindler of Yugoslavia’’’, News Reports, Lootedart.com, September 2001, https://www.lootedart.com/MFEU4T15383.

[3] For more on this, see the introduction to this volume.

[4] Wiltrud Mersmann, ‘Das Elfenbeinkreuz der Sammlung Topić-Mimara’, Wallraf-Richartz-Jahrbuch 25 (1963): 7–108.

[5] Also see Charles Little’s essay in this volume where he discusses Mütherich’s friendship with Mersmann.

[6] For the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s purchase of the Cross, see Charles Little’s essay in this volume.

[7] For these and other people mentioned, see the Dramatis personae in this volume.

[8] Christopher Marlowe, The Jew of Malta, act 4, scene 1.

[9] Neil Stratford, ‘The Cloisters Cross’, The Burlington Magazine 156, no. 1336 (2014): 464.

[10] Ursula Nilgen, ‘Das Große Walroßbeinkreuz in den “Cloisters’’’, Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 48, no. 1 (1985): 39–64.