The concept of the continuous page straddles at once some of the oldest and some of the most contemporary ideas about images and image-making from across the globe.

On the one hand, the phrase evokes historical artefacts of a diverse ancient world: scrolls and rolls of papyrus, parchment, and paper. In older Mediterranean and European cultures, especially those of ancient Greece and Rome, continuous forms were prominent features of the material sphere, to such an extent that their cylindrical shapes have since been formed into a symbolic shorthand for the entire abstracted classical tradition (fig. 0.1). Likewise, the long-standing presence of scrolls and rolls in the visual cultures of the Middle East and Asia affirm their powerful status within Eastern aesthetic traditions stretching back for several millennia (fig. 0.2). The continuous page stirs these distant pasts in our imagination.

Yet on the other hand, the act of scrolling has also grown into the most common form of interaction between people today and their future-facing media. More than typing on a keyboard or clicking a mouse, we now routinely swipe across touchscreens and trackpads to scroll through reams of infinite hypertext. Digital information from global news and money markets to personal messages and calendars forever unfurl on-screen at our fingertips, and the tactile technologies which allow us to do so—once described by Apple’s Steve Jobs as a groundbreaking kind of machine-driven ‘magic’—now feel a routine, even requisite part of our day-to-day engagement with contemporary media.

The space between these two chronological extremes is likewise packed with scrollable ancestors and precursors, a profusion of different makers and users who have repeatedly returned to the physical and conceptual elasticity of the scrolling format: medieval legal rolls, early modern printed city panoramas, reams of handmade wallpaper, photographic film, mass-produced cloth, ticker tape. How might we begin to tie down this cross-chronological, pan-geographical plethora of extendable, contractible, manipulable, scrollable things?

The most common response to this question by historians of objects, literature, music, and performance alike, has been to hone in exclusively on the peculiarities of context, elaborating the aesthetic details of individual scroll and roll traditions alongside the specific practical and conceptual concerns of their moment.[1] What was it, they ask, about a certain period or place or practice that prompted the construction of continuous pages, with their answers ranging from matters of material constraint to functional convenience and overarching concept. In this book, our approach to the continuous page is similarly grounded in context: across fourteen chapters, we add to a growing awareness of continuous forms through focused, individual explorations ranging from medieval Japan, Egypt, and England to modern and contemporary India, Europe, and America, via Renaissance Italy and the early modern Netherlands. However, in bringing these discrete instances together in a single space, the chapters that follow also aim at something far bigger than isolated historical vignettes: they offer a unique opportunity to build conceptual bridges back and forth across a typology of object. In particular, this book tries to facilitate such cross-readings through the arrangement of its contents. Its chapters do not appear simply in chronological order. Given the global scope of its contributions, the bunching together of objects and ideas from vastly different geographies under rigid (often Western) period definitions felt at best contrived and at worst flattening. Instead, to simultaneously forge links whilst recognising difference, our chapters are grouped along four broad themes: ‘History’, ‘Performance’, ‘Bodies’ , and ‘Technology’. Each of these ideas represent a particularly potent aspect of the continuous page around which even radically different objects might begin to gather and cohere.

The chapters in ‘History’ acknowledge that continuous forms—whether drawn, painted, printed, or sculpted in three-dimensional or architectural settings—inevitably bring with them significant historical baggage. In a Mediterranean context, we might trace this notion all the way back to late antiquity and a subtle yet fundamental shift in the formatting of written documents that seems to have taken place at some point over the third and fourth centuries CE. To judge from surviving objects, it was at this moment that the codex book began to slowly supplant the scroll and roll of antiquity, prompted by both the collapse of a consistent, international Roman Imperial bureaucracy and the growing popularity of Christianity across the region, a religion distinctly of the codex.[2] Significant debate remains over precisely why and how such a transition was made, but this moment at least marked a shift in mindset that was to have ongoing repercussions for these two types of object and their representation in the West. From medieval evocations of the prophetic, pre-Christian past to Neoclassical forms of the early modern period, the scroll and roll present themselves as easy routes into the visual language of the antique, acting as a signpost of religious or historical accuracy and, through this, a carrier of classical authenticity and authority.

The connection of continuous pages to the past, however, is more than a mere iconographic contrivance. Whilst scrolls and rolls might have been overtaken by codices in many religious and secular realms across late antiquity, the format continued to flourish in the medieval and early modern archive, where they predominated in the keeping of financial, legal, and administrative records. We need only bring to mind the roughly nine-kilometres-worth of rolled laws stretching back to the 1490s that are still preserved today in London’s Parliamentary Archives (fig. 0.3). This fashion in document-making likely had a practical rather than conceptual foundation: a roll consisting of glued membranes of unbroken parchment could be much more easily expanded to contain new information than the hermetically stitched and bound quires of a codex, allowing for the ready growth or contraction of working documents and records. Still, this sustained association of scrolls and rolls with the preservation of a precise historical record further bolstered a growing link between the continuous page and the weighted jurisdiction of the past.

This trope was equally powerful across the medieval and early modern Middle East and Indo-China. Rather than gradually supplanting codices, here it was the sustained historical importance of scrolls and rolls which saw them enshrined with a powerful authority, particularly the continued ritual values of unfurling Buddhist, Hindu, and Jewish holy texts, and the ongoing political valencies of scrolls in Japanese and Chinese Imperial courts. Proof of this tradition’s potency can be found in the more recent work of contemporary artists who present themselves as the latest inheritors of this long, rolling, scrolling lineage. Consider the tightly wound works of Hadieh Shafie, whose colourful arrangements of bundled handscrolls draw simultaneously on historic Islamic document-forms and the more modern, post-Revolutionary rhetoric of censorship and concealment in her native Iran (fig. 0.4).[3] Xu Bing’s canonical installation Book from the Sky (1987–91) likewise draws on ancient forms to craft an evocative, all-encompassing space for the viewer to inhabit beneath enormous draped scrolls of Chinese pseudo-characters, their continuous forms carrying powerful meaning even when their nonsensical text carries none.[4] The first three chapters of this book, considering Hebrew rotuli, Northern renaissance classicising prints, and the historically freighted feminism of Nancy Spero, all similarly follow the continuous page backwards into the past.

Chapters in our the second section, ‘Performance’, turn from notions of history and time to the more immediately immersive capacities of the continuous page. Perhaps more than any other type of reading, scrolls and rolls have a tendency to push their makers and users into motion. Many roll- and scroll-objects from various times and places have hinged quite fundamentally on the temporal ability of their continuous pages to unfurl and thus to perform. This might be a performance enacted for the benefit of only one individual at a time, as appears to have been the case with a surprising tranche of eminent modern European and American fiction. Works by the Marquis de Sade, Edgar Allen Poe, Jack Kerouac, and Kurt Vonnegut all survive in roll form, crafted either through the exigencies of their making—de Sade, for instance, was imprisoned in the Bastille without writing materials—or more deliberately through the continuous page’s ability to reenact the immediacy in free-flowing verse. Alternatively, scroll performances might be undertaken to benefit a whole assembly of viewers. Medieval Exultet rolls, parchment reams of prayer and song, were designed to be unrolled by officiants from high up on the pulpit during particular ritual moments of Easter celebrations, their images and texts flowing downwards in a continuous stream for the congregation below.[5]

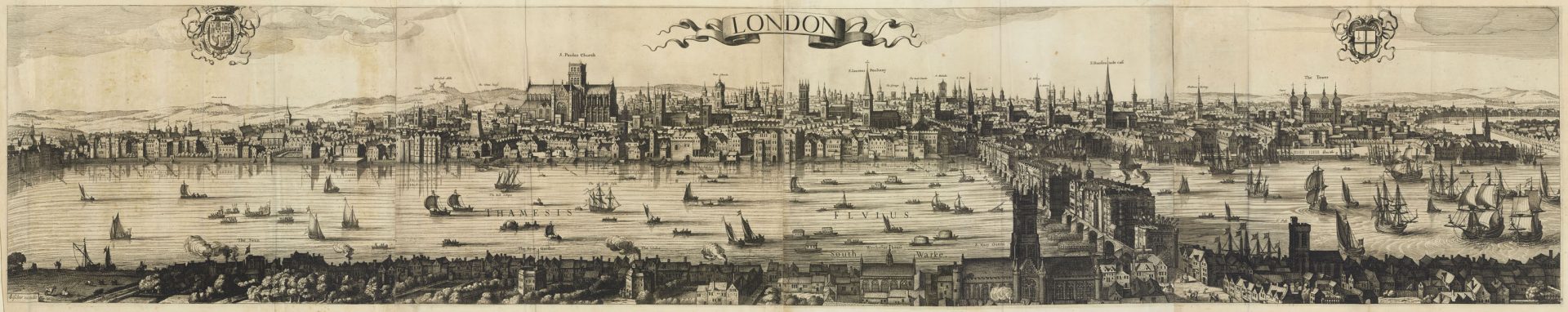

Given this heightened possibility for subtly elaborative presentation, the continuous page has often been championed as a consummate medium for capturing performances themselves, the extendable lengths and breadths of scrolls and rolls seen as ideal for translating certain phenomenological experiences of time and space continuously in two dimensions. It might be whole events that so unfurl—explorative journeys, historic battles, stately processions (fig. 0.5)—or it could be singular, capacious vistas whose long scroll-forms granted time for the eye to lazily wander their hills or streets back and forth. Examples of the latter range from enormous, individual undertakings—for instance Melchior Lorck’s Prospect of Constantinople(1559)—through to cheaper, printed panoramas (fig. 0.6) and, later, photographic strip-visions of unfolding urban space (fig. 0.7).[6] The three chapters in ‘Performance’ grapple with this remarkable ability of continuous pages to perform a rolling view of the world, from medieval Netherlandish monasteries and Imperial triumphs of the Northern Renaissance, to the storytelling of traditional Bengali patuas.

The chapters collected together in our book’s third section, ‘Bodies’, continues this performative concern but focuses it through a more corporeal lens. After all, if continuous pages with all their unrolling and unwrapping can be thought of as inherently performative—the pinning back of springing parchment, the regathering of rolled ends—then this performance is an insistently bodily one. Perhaps the best-known of modern artworks to elaborate this idea is Carolee Schneemann’s provocative Interior Scroll (1975), a performance in which the artist disrobed and then pulled a small paper scroll from her vagina, reading the piece as it unfurled.[7] The continuous capacity of the scroll format afforded Schneemann an unbroken umbilical connection between body, object, and voice, an idea that chimes—consciously or not—with far older performance practices that also united scrolls with bodies. The apotropaic potential of rolled amulets, for instance, has been a popular feature of medical and ritual practice in a number of cultures worldwide.[8] These paper or parchment scrolls might contain either scribbled charms, the names of saints and deities, or potent words and numbers written in acrostic and palindromic form, all of which would originally have been kept close to the body. The smallest of such scrolls are tiny, fragments only a few centimetres wide, and were likely worn at the chest around the neck, tucked into clothing, or attached to the belt in small leather cases. Longer pieces exist, however, which direct their users to dramatically unravel their substantial reams and wrap them in their entirety around the wearer’s body, conferring the power of their apotropaic texts in a ribbon-like cloak. Some, like the intricate fourteenth-century Mamluk roll currently housed in the Al-Sabah Collection of the Dar Al-Athar Al-Islamiyyah in Kuwait, extends well over ten metres long (fig. 0.8).[9] Peppered with illustrated numerical grids, plaques, and even miniature weapons, the scroll’s imagery accompanies a talismanic Qur’anic text written in Arabic, the words of which give a good sense of the dramatic range of fears and anxieties potentially felt by the owners of such objects. Initial sections address notions of kingship, perhaps to be read aloud as a supplication before entering the court of a ruler or king; other elements seek protection from more supernatural powers, including prayers to annul magic and prevent the evil eye; subsequent passages relate more directly to health and wellbeing, offering cure from headache, eye pain, and fever; and yet more parts of the scroll claim to ensure victory in military campaigns, goodwill for a journeying horseman and his horse, and untroubled passage when voyaging by sea. The chapters grouped together in ‘Bodies’ acknowledge just these sorts of diverse bodily capacity, considering an English parchment birth girdle, an Italian hospital frieze, and an Imperial Japanese scroll, all of which entangle the human form with both issues of health and more philosophical evocations of bodily presence.

Our book’s final grouping of chapters cluster around the theme of ‘Technology’, projecting ideas of the scroll and roll forward through a set of continuous pages made possible, at least in part, by modern technological advances. In this sense, they recognise that scrolls and rolls of all types have always been intricately bound up with matters of technical progress and futurity. Continuous objects have been closely linked to many of the busy mechanical leaps of the machine age across the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Under this umbrella we might pool a rich range of automatic, scrollable objects and processes, everything from cylinder printing and cinematic film reels to blurry microfiches, children’s toys, and even the punched rolls of self-playing pianos. More recently, though, the advent of digital spaces in the Internet Age regularly produces uncanny parallels between our contemporary moment and historic continuous precedents. Contemporary artists again have been quick to utilise the forward-looking backwardness of the digital era as a site for particularly engaging interventions. In 2015, for instance, Cornelia Parker coordinated the sewing of a piece entitled Magna Carta (An Embroidery), which recreated in exquisite, stitched detail the entirety of the Wikipedia entry for the thirteenth-century treaty on its 800th anniversary (figs 0.9–0.11). Stretching to an impressive thirteen metres in length, the laborious, steampunk quality of the embroidery piece unites the twin extendable forms of traditional needlecraft and hypertextual space into one continuous ream.[10]

The technological short-circuit presented in a work like Parker’s serves to highlight an obvious historiographical issue which for some has time dogged the analysis of the long, open-ended artworks of the continuous page and with which this book has also had to grapple. By their very nature, scrolls and rolls—whether painted, printed, or sculpted—are excessive things that are extremely difficult to display in their totality within museum settings, and likewise impossible to satisfyingly reproduce within the bounds of the codex-form academic book. Until recently, scholars and publishers had only two options. They could preserve a scroll or roll’s conceptual continuity by reproducing it in its entirety, perhaps across a double-page spread, but in so doing compress what might be a ten-metre-long object into a thin strip inevitably too small to examine in detail. Or, alternatively, they could showcase a scroll or roll’s images and text as a series of individual details printed at a reasonable size, but in so doing dismember the continuous flow of the object, slicing it up across multiple framed plates through the physical restraints of a book’s bound folios.

Happily, digital developments in online publishing have allowed this book to side-step such problems. Alongside almost all of our chapters, we include a number of fully digitised scrolls for the reader to browse, interlacing scholarship with a far more direct experience of these historical objects by recreating, in so far as is currently possible, the unfurling qualities of original works through large-scale, scrollable images. It is three technological journeys of this nature that the final chapters of our book also examine, considering sketches for novel film special effects, mechanical scrolls of the avant-garde art world, and the continuous typescripts of Beat writing.

This book could have been written many, many times over, including an entirely different set of contributions which shed careful light on an entirely different set of objects from yet more historical periods and cultures. The danger of crafting scholarship within the infinite, scrolling space of a digital document, however, is that of falling into a continuous typescript, a never-ending stream of writing. At some point, the ever-expanding bounds of this book simply had to stop and take stock. Nonetheless, what we hope to have presented is a starting point for tackling the multiple challenges of the continuous page, addressed not only as individual historical units but as a connected community of scrollers and unrollers.

Jack Hartnell is Senior Lecturer in Art History at the University of East Anglia, where his research and teaching focus on the visual culture of late medieval and early modern medicine, cartography, and mathematics.

Citations

[1] To take a broad, general sample, see: Melissa McCormick, Tosa Mitsunobu and the Small Scroll in Medieval Japan (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2009); Geza Vermes, The Complete Dead Sea Scrolls in English (London: Penguin, 2004); Shane McCausland (ed.), Gu Kaizhi and the Admonitions Scroll (London: British Museum Press, 2003); Odile Nouvel, French Scenic Wallpaper, 1790–1865 (Paris: Flammarion, 2000); Thomas Forrest Kelly, The Exultet in Southern Italy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996); Jacques Mercer, Ethiopian Magic Scrolls (New York: Braziller, 1979).

[2] Colin H. Roberts and T. C. Skeat, The Birth of the Codex (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1984); Kurt Weitzmann, Illustrations in Roll and Codex: A Study of the Origin and Method of Text Illustration (Princeton: University Press, 1970).

[3] For more on Shafie see Linda Komaroff, Islamic Art Now: Contemporary Art of the Middle East (Los Angeles: LACMA, 2015).

[4] On Xu Bing, see Hsingyuan Tsao and Roger T. Ames (eds), Xu Bing and Contemporary Chinese Art: Cultural and Philosophical Reflections (Albany NY: SUNY Press, 2011).

[5] On Exultet rolls see Kelly, The Exultet.

[6] On Lorck, see Nigel Westbrook, Kenneth Rainsbury Dark, Rene van Meeuwen, ‘Constructing Melchior Lorichs’s Panorama of Constantinople’, Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 69:1 (2010): pp. 62–87. On printed panoramas, see Erkki Huhtamo, Illusions in Motion: Media Archaeology of the Moving Panorama (Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 2013); Ralph Hyde, ‘Myrioramas, Endless Landscapes: The Story of a Craze’, Print Quarterly 21:4 (2004): pp. 403–421.

[7] For more on Schneemann, see the thoughts collected in Imaging Her Erotics: Essays, Interviews, Projects (Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 2003).

[8] For more on such amulets see Donald C. Skemer, Binding Words: Textual Amulets in the Middle Ages (University Park: Penn State University Press, 2006); Peter Murray Jones, ‘Amulets and Charms’, in Miri Rubin (ed.), Medieval Christianity in Practice (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009), pp. 194-99.

[9] My thanks to Yasmine Al-Saleh for her contributions to this volume and for sharing her thoughts on the Al-Sabah scroll. For more on this genre of images in an Arabic context, see Yasmine Al-Saleh, ‘“Licit Magic”: The Touch And Sight Of Islamic Talismanic Scrolls’ (PhD diss., Harvard University, 2014).

[10] In a strange, digital mise-en-abîme, Magna Carta (An Embroidery) now has its own Wikipedia entry (accessed 20 April 2019). The complete embroidery is available in large scale there, including a note on permissions from the British Library: ‘The embroidery, and photographs of it, are available for reuse on the same terms as Wikipedia content’.

Download PDF

The Continuous PageDOI:10.33999/2019.01