Regardless of our individual interests, specialisms or training, I think we would all agree that for a conservation strategy to be successful it must be well informed. When dealing with wall paintings, this requires not only an understanding of the artwork itself – its composition and condition, the environmental and anthropogenic challenges to which it has been subjected over time – but also of the structure of which it forms an integral part.1 So often, we must turn detective as we endeavour to construct a physical history of the paintings entrusted to our care, striving to understand how they came to be in the condition in which we find them. Too often it is a time-consuming, fruitless quest, hampered by a scarcity of records and an everchanging guard of custodians. Resigned to a frustrating vacuum of information, we endeavour to forge a way ahead, to diagnose the symptoms and deduce the causes, to formulate a plan which we hope will ensure the scheme is safeguarded for the future. How much better might we all fare if records of past observations and interventions were made freely accessible, in one place, and our resources shared in a spirit of constructive collaboration!

A utopian vision perhaps, but for those involved in the study and care of wall paintings in the British Isles, advocacy for the transformative influence of good record keeping is nothing new, as a brief survey of the origins of our field will demonstrate. Indeed, it was in the careful documentation of medieval wall painting schemes that modern-day conservation found its roots. Building on the legacy of the antiquarian movement, Charles E. Keyser (1847-1929), erstwhile London stock-broker and subsequent president of the British Archaeological Association, was the first to publish, in 1871, a twenty-four page List of Buildings having Mural Decoration, with a third expanded edition being made available in 1883 (Figure 1).2 It is arguably, however, to the son of a Welsh railway inspector born around just that time, that our greatest collective debt is owed. With an auspicious talent for draftsmanship and chemistry, and working under the mentorship of the progressive architectural conservator W.R. Lethaby,3 Ernest William Tristram (1882-1952) advanced to become Professor of Art & Design at the Royal College of Art (Figure 2). It was a surprising appointment, perhaps, given that he was, according to one of his students, ‘far more interested in the Black Prince than Le Corbusier’, devoting his every free moment to the study and recording of medieval mural schemes.4

At Leeds, in December 1933, an exhibition was mounted of a selection of the several thousand meticulous watercolour copies Tristram had by then produced, each testament to his extraordinary ability to accurately record not only a painting’s subject matter, but also to capture its aesthetic and condition (Figure 3).5 Working with support from The Pilgrim Trust and The Courtauld, and with the indefatigable assistance of Monica Bardswell,6 three gargantuan volumes ensued.7 Copiously illustrated with Tristram’s own copies, they remain – some seventy years on – the preeminent record of medieval mural painting in England and its borders. And while Tristram’s subsequent ventures into the treatment of wall paintings using wax-based consolidants proved to be detrimental,8 there can be little doubt that no other individual did more in his career to promote an appreciation of British wall paintings or the case for conserving them.

While the Church of England had, by this time, already begun to make provision for wall paintings in its care,9 the creation in 1953, under Francis Eeles (Figure 4), of an expert committee as a joint venture by the Central Council for the Care of Churches and the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings, marked the development of a first collaborative attempt to document and give direction to the field of wall painting conservation in Britain.10 Launched, significantly, a year after Tristram’s death, the Committee sought to ascertain the extent of the nation’s mural heritage and those who had worked on them. Among the recommendations made, the committee undertook to commission a survey of the condition of wall paintings throughout England.11 Although the Church continued to maintain its own records, regrettably the ambition for a more joined-up repository of information, combining ecclesiastical and secular schemes of wall painting, never came to fruition.

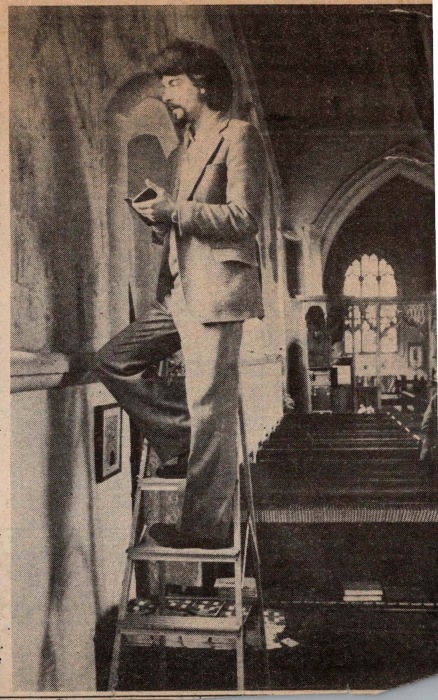

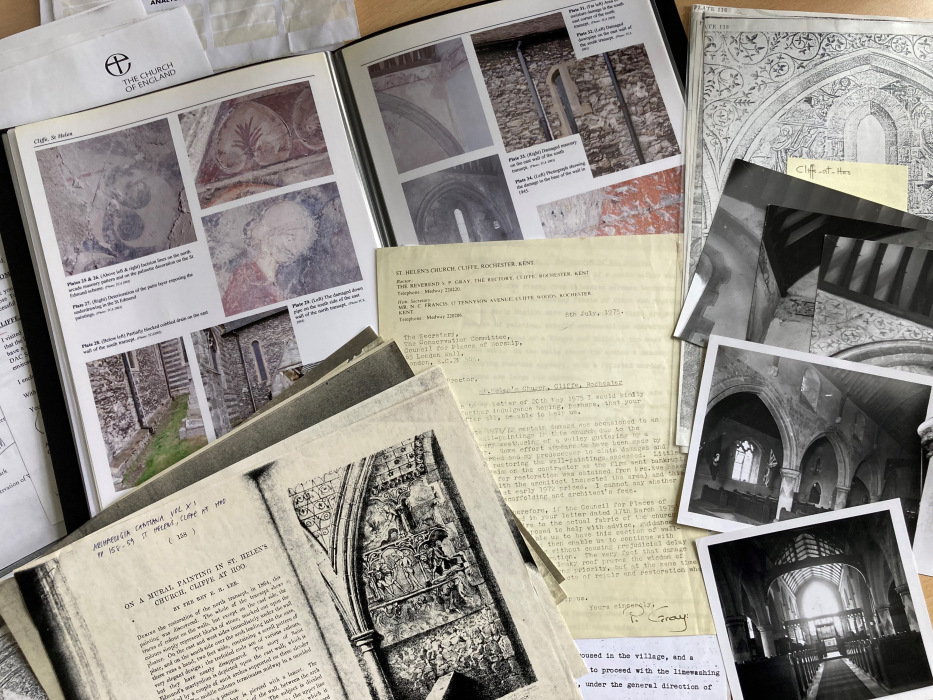

In 1980, following ‘a period of increasing concern about the plight of medieval wall-paintings in this country’, the Leverhulme Trust awarded The Courtauld a major grant to enable David Park, as a Research Fellow, to undertake a four-year-long ‘Survey of English Medieval Wall Paintings’ (Figure 5).12 With an advisory committee lead by the V&A’s then Director, Sir Roy Strong, and Professor Peter Lasko at the Courtauld, and with the photographic services of the Royal Commission on Historical Monuments in England (RCHME) at their disposition, they hoped that the Survey would ‘provide a written and photographic record of all surviving wall paintings in England’ upon which ‘future studies and conservation programmes can be based’. David continued to work tirelessly on the Survey, which evolved well beyond the scope of the original project to include non-medieval schemes of decoration at sites throughout the British Isles, until his retirement in 2018, while simultaneously establishing – with his colleague Sharon Cather – the country’s first and only postgraduate training programme dedicated exclusively to the conservation of wall paintings. It is testament to David’s diligence and unwavering commitment that the Survey has been passed on to us in its present form, a chronicle of wall painting history in Britain spanning a century, comprising not only conservation reports and images, but also carefully annotated extracts of published literature and previously unpublished research contributed by fellow scholars in the field. Of particular interest is material bequeathed from the archives of such pioneering wall painting conservators as Tristram himself, and Eve Baker, the exquisitely illustrated research notes of renowned antiquarian Edward Croft-Murray, and Muriel Carrick’s detailed documentation of domestic decorative schemes.

Long feted by those in the know as a treasure-trove of invaluable information, access to the archive was limited to those who were able to secure a visit in person. It became increasingly clear, however, that for the Survey to achieve its original purpose and potential, for it to inform the way we appreciate and conserve our wall paintings, this resource needed to be made much more widely available, to be digitised and published online. Previously hindered by the absence of the considerable resources required to achieve this, the ambition finally became attainable in Spring 2022, when The Courtauld secured three major grants – from the Paul Mellon Centre, Pilgrim Trust and Marc Fitch Fund – towards the first stage of the National Wall Paintings Survey Project, a three-year initiative to fully catalogue and partially digitise the Survey archive, allowing it to be made available through a publicly accessible database.13 It has been (and continues to be) a colossal undertaking, but one that has benefited immeasurably from the support and insights of an advisory group comprising stakeholders from across the academic and heritage communities, as well as conservators working in private practice.14 The overarching aim of the Survey Project as we saw it was two-fold: to radically improve public access to the archive and, in so doing, to stimulate important new research into the significance and conservation of Britain’s mural heritage. What follows is an account of the way in which the project was approached and the strategies we have adopted throughout that process.

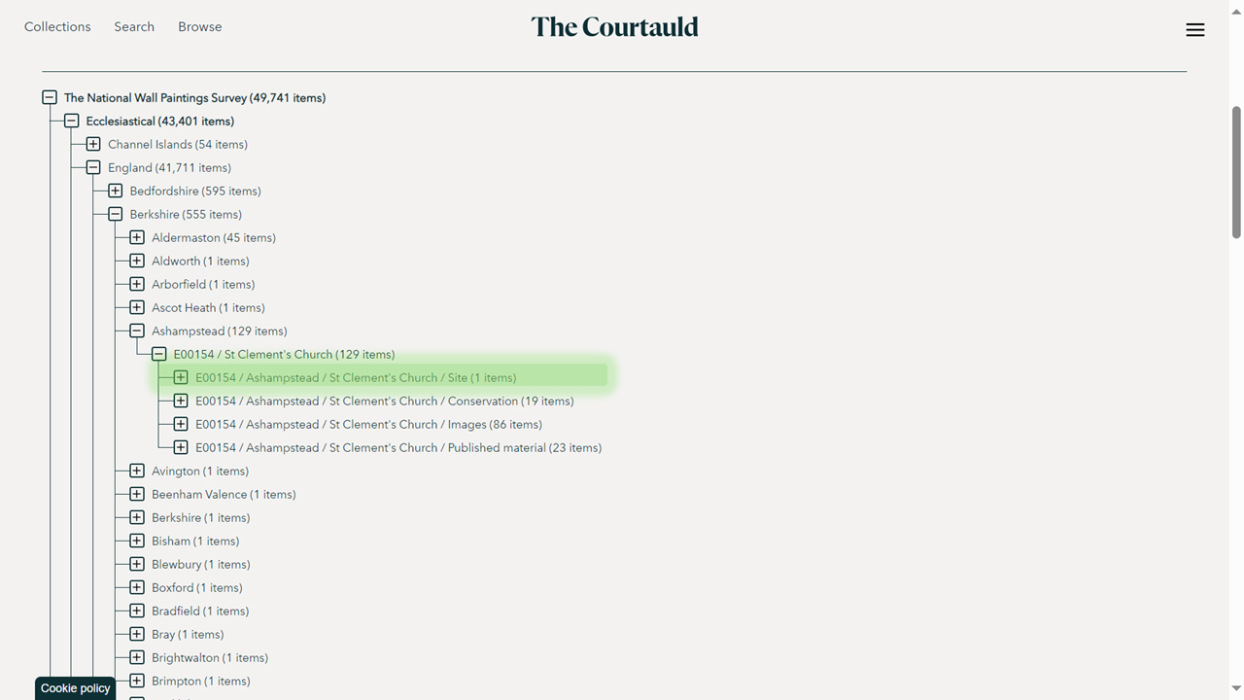

The Survey comprises some sixty linear metres of files, organised geographically, by county, encompassing material pertaining to some 5,365 ecclesiastical settings and a further 2,549 secular sites, many with multiple painting schemes (Figure 6). An initial project year (Phase 1, February 2022 to January 2023) saw the archive fully audited and, with the assistance of two highly proficient research assistants, electronically catalogued.15 Over the course of nine months, the contents of each file was manually sorted into subcategories of material in preparation for cataloguing using Microsoft Excel, a process which captured both basic ‘tombstone’ data – such as site location, building name, painting descriptions and dates – and an overview of the types of material held.16 Simultaneously, trials were undertaken to inform decisions about how to proceed with digitisation across the Survey and a workflow developed that could be rolled out in Phase 2 of the project. In contrast with many other archival collections, the Survey comprises an extraordinarily wide variety of material in a range of text- and image-based formats for which very high-resolution photographic digitisation was ill suited. Sample material was instead scanned using a desktop multi-page document scanner based on standards established by the National Archives.17 Text-based material was scanned using optimal character recognition (OCR) technology to generate a searchable PDF-A, while images were saved as JPEGs.

Towards the conclusion of this first year, a questionnaire-based consultation exercise was undertaken across a substantive sample of our target end-users,18 and the findings used to inform our approach in building the database, which would be published using Vitec’s Memorix Maior,19 the same Spectrum-compliant collections management platform used to host The Courtauld’s recently digitised photographic collections.20 This research process afforded an improved understanding of the material our users were most interested in accessing, and for which purposes, and the ways in which they sought to interact with this data, as well as canvassing their potential involvement in sustaining and enriching the archive going forwards. We were especially keen to reach respondents involved in the day-to-day care of wall paintings at diocesan and parish level, as well as those responsible for privately owned sites. The data gathered from this exercise was also used to identify and ensure the digitisation of the Survey’s most important assets. Mindful of the limited resources available to us in this initial project phase, and based on the consultation feedback, we elected to prioritise digitisation of those sites for which we held both conservation-related documentation and historic images,21 as this material seemed to have the greatest potential to be impactful in terms of informing more sustainable conservation practices.

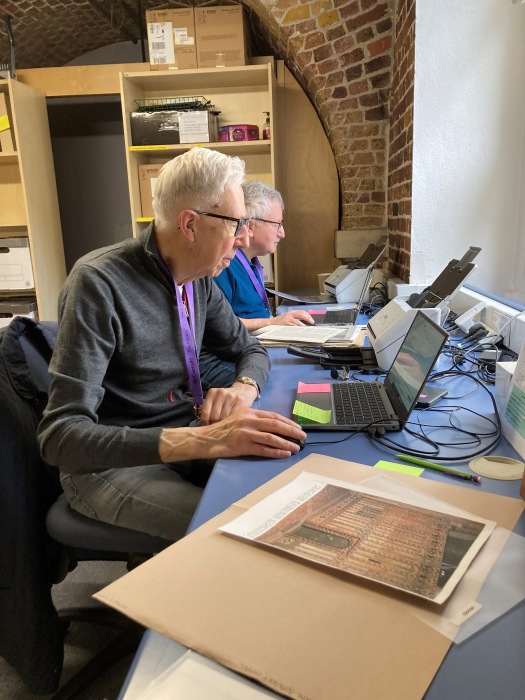

The principal focus of Phase 2 of the project (February 2023 to January 2025) has been the digitisation of material associated with some 1,200 individual sites, work that has been undertaken in collaboration with an exceptionally dedicated team of twenty-five volunteers (Figure 7). Almost all of them had previously been involved with the Courtauld’s Conway Library digitisation project, some over many years.22 Many are retired professional people, while others are contemplating a change in career or in the process of completing research degrees, most with no previous affiliation to art history. Unequalled in their enthusiasm, though with varying degrees of computer literacy, they have undertaken digitisation following a detailed protocol, using a predetermined file-tree structure which emulates the physical organisation of the archive. Thanks to their commitment, significant headway has been made over the last 18 months, and by the end of Phase 2 we will have digitised around one fifth of the Survey, including almost all of the UK’s cathedrals alongside many lesser-known schemes in country churches and domestic settings.

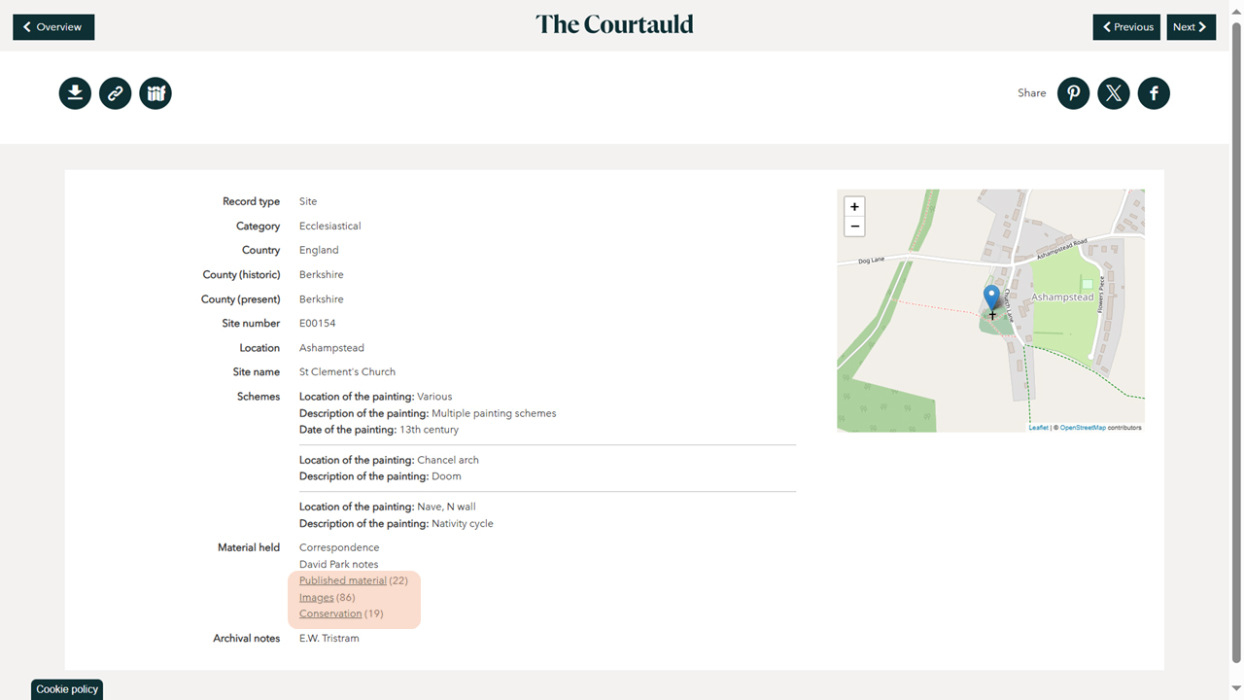

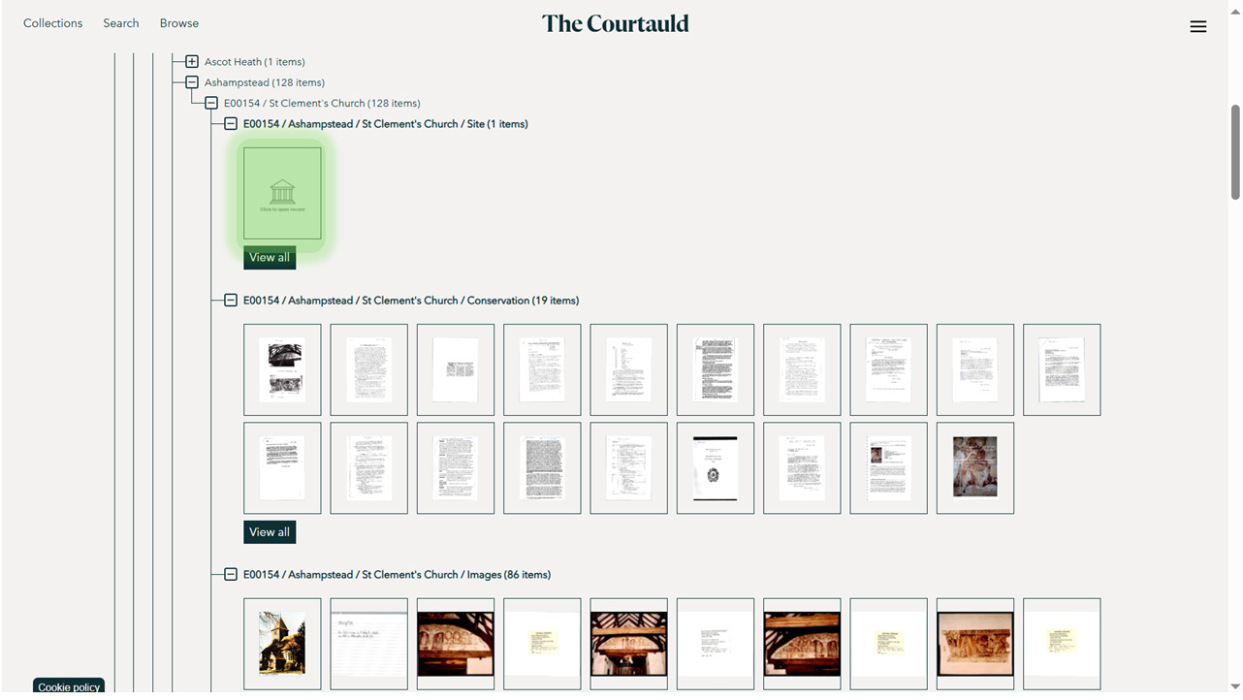

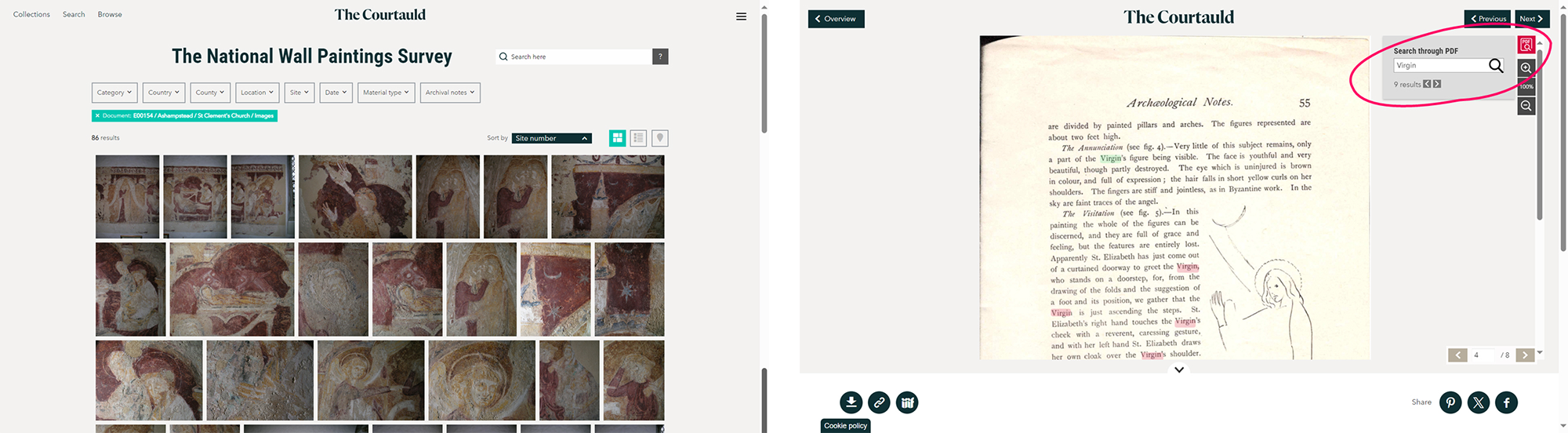

The catalogue and associated digital assets have now been imported into their new online environment, which in itself is the product of a year-long creative journey. Launching at the beginning of February, it sits alongside the Courtauld’s other digital collections. In keeping with the physical archive, the Survey database is navigable using a file tree arranged by painting type and geographical location, making it very easy to navigate quickly to a specific known wall painting (Figure 8). Each site (usually a building) has an individual record page comprising geographical data alongside a description and date of its painting scheme(s), and a list of the types of information held (Figure 9). Where this material has already been digitised, there are hyperlinks to subfolders of digital content pertaining to the painting scheme(s) (Figure 10). Users can virtually browse the folders of assets and scrutinise individual documents or images of interest, using the zoom functions and text search capabilities (Figures 11 & 12), or choose to download them under the terms of a Creative Commons user agreement.

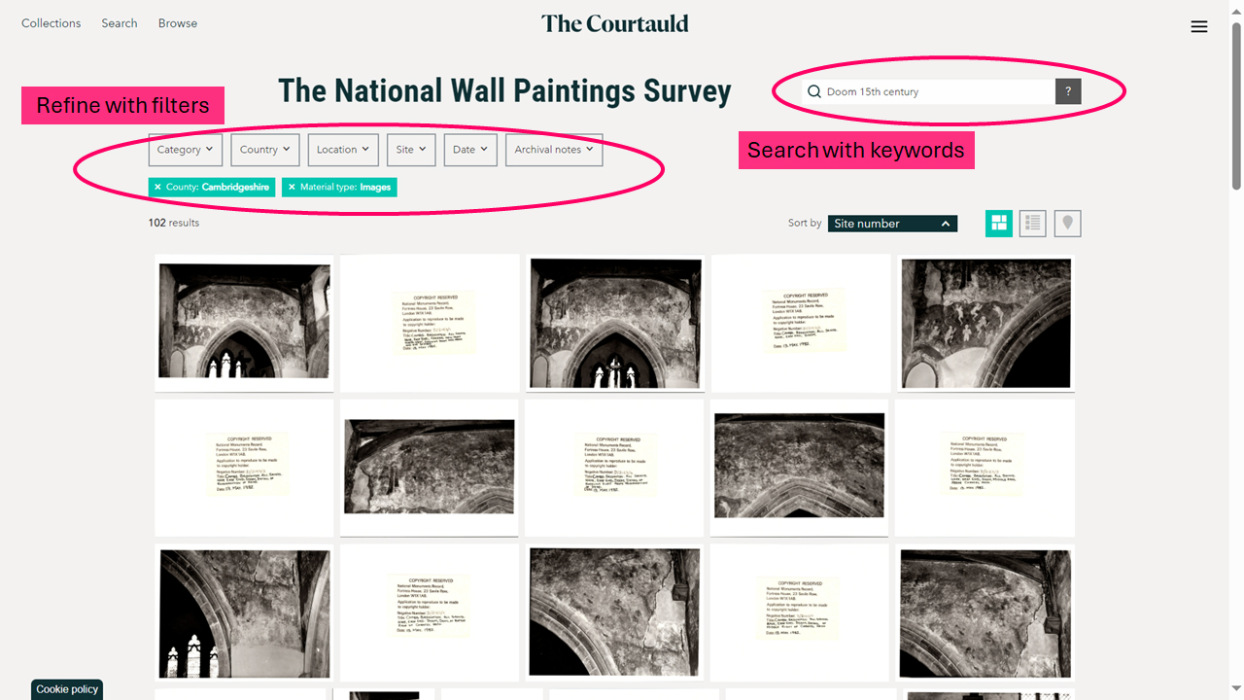

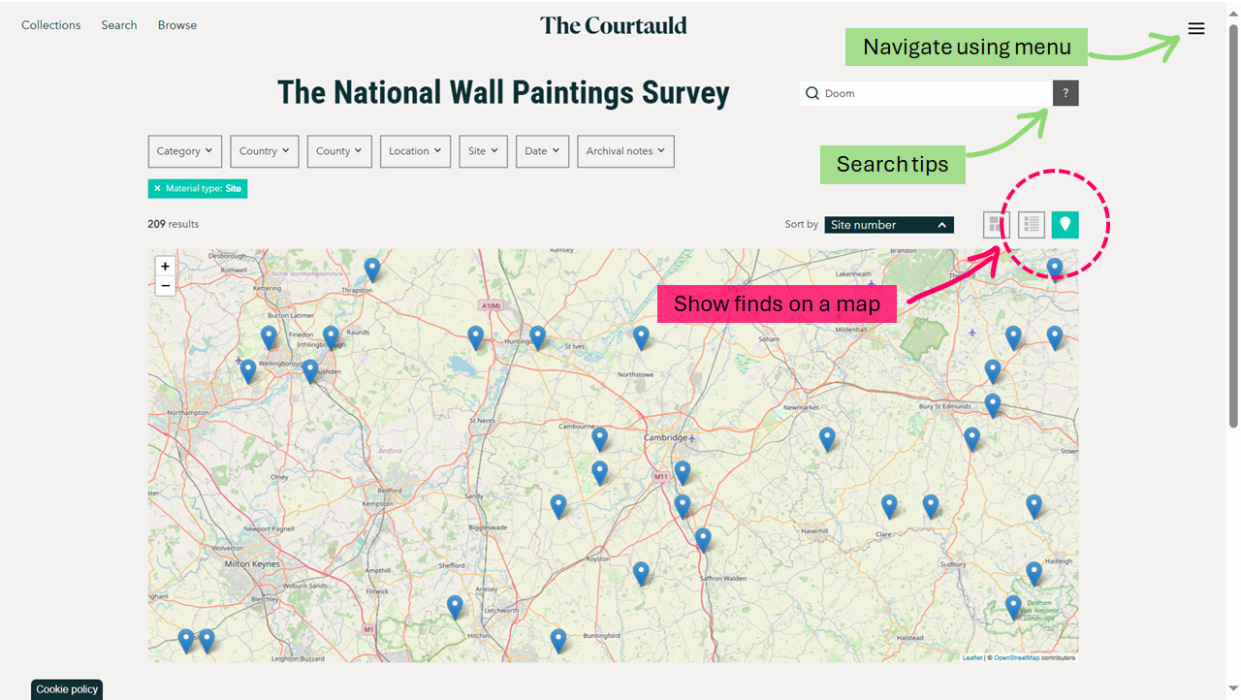

For those who enjoy a more serendipitous or thematic approach to research, it is also possible to explore the archive through a ‘search’ page, using individual or combined terms of their choice, with the potential to refine their ‘finds’ using predetermined filters (Figure 13). For the first time, it is now possible to search the Survey iconographically, or by date, and to map the physical distribution of selected sites (Figure 14). In due course, when time allows and the relevant data has been added, there will be the potential to map specific conservation interventions, enabling us to perceive not only trends in treatment but the hitherto unremarked interrelationships between them. It is a work in progress, but a journey with almost limitless destinations.

While I have been constantly delighted by the enthusiasm of both old colleagues and new acquaintances for what we are trying to achieve with this project, it would be disingenuous to say that the process of publishing an archive of this type has been without its challenges. I have learned perhaps more about copyright law and data protection legislation over the last three years than the wall paintings which I am concerned to safeguard, but it is an essential strand of the complex process we are navigating, not least out of respect for all those who have contributed to the Survey – this will only work if everyone is on board. Rigorous screening is being undertaken (again by volunteers) to identify the rights holders of all the material digitised to date, with the necessary permissions being sought to allow us to share these resources on the database.23 We are profoundly grateful to every individual and organisation who has given their permission for material they have contributed to be shared.

Our approach to the Survey’s online publication emulates the pragmatic and sustainable approach adopted by other recent successful digitisation projects, which have provided us with a model balancing public benefit with due diligence.24 In keeping with the terms of our grant-funding, we will aspire to make available as much of the Survey as possible under a Creative Commons licence. Out of respect to our contributors and in order to encourage the widest possible participation, we are using the most restrictive form of licence (CC BY-NC-ND) which precludes commercial and derivative use of that material.25 While the sheer volume and diverse sources of the material held in the Survey make it impracticable to seek permission from each and every individual rights holder, the website is rooted in current UK Copyright and data protection law, and underpinned by a robust and transparent take-down policy.26

Having now successfully digitised around a fifth of the archive’s holdings, we aspire to complete the remainder in a subsequent major project phase and, building upon the valuable partnerships we have forged, to promote the Survey as the principal national repository for documentation relating to British wall paintings. In truth, the conclusion of the current phase of the project marks just the beginning, for only now are we starting to unlock and explore the potential of the material the Survey contains. Collaboration with those working across the academic and heritage sectors will continue to underpin our research going forwards. We are particularly interested in examining those who pioneered the conservation of wall paintings in the UK and the ways in which approaches have evolved over the past century. The creation of a digitised catalogue has already enabled us to interrogate the archive in exciting new ways, revealing information that will prove invaluable in informing how we can better care for our mural heritage.27

It is our sincere hope that, following the website launch, and as awareness of the project continues to grow, the National Wall Paintings Survey database will become an increasingly dynamic and collaborative space in which colleagues and individuals from all backgrounds can come together to enrich our understanding of our painted past. Public enquiries to the Survey have increased by more than sixty percent since the first project year, with the vast majority of our users now originating from outside The Courtauld and we have been particularly encouraged to see an uplift in enquiries from heritage bodies, parishioners and conservators. It is in this area, especially, that the value of the database lies, with a real potential to inform successful conservation outcomes (Figure 15). Raising awareness not only of the archive, but of British wall paintings generally, among a broader spectrum of people, has been a central aim of this project. To this end we are excited to be developing an exhibition that will showcase British wall paintings and their conservation, scheduled to feature in The Courtauld Gallery’s ‘Project Space’ in Spring 2026, with many associated opportunities for educational engagement.

The National Wall Paintings Survey project has afforded us the opportunity to develop rewarding partnerships with the custodians of other important archives concerned with the history and care of wall paintings in Britain, and it is especially gratifying that representatives of so many of them have been able to take part in this symposium. Perhaps even more important, though, has been the opportunity for engagement with all those individuals who work with wall paintings in the UK – whether as art historians, conservators, buildings engineers, volunteers or church wardens – for it is their work which forms the substance of the Survey archive and upon whose collaborative efforts the conservation of the nation’s wall paintings depend.

1 See S. Cather, ‘Assessing causes and mechanisms of detrimental change’, in Conserving the Painted Past: Developing Approaches to Wall Painting Conservation, ed. R. Gowing & A. Heritage (James & James, 2003), 64-74.

2 Keyser was approached to write the original pamphlet ‘as a voluntary task’ by R.H Soden Smith, then Director of the South Kensington Museum, with an expanded version released in 1872, and a final third edition in 1883; C.E. Keyser, A List of Buildings in Great Britian and Ireland Having Mural and other Painted Decorations (H.M. Stationary Office, 1883), iv.

3 Lethaby was a fervent supporter of the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB), arguing, in his tenure as Surveyor of the Fabric at Westminster Abbey, for more sympathetic and historically accurate restoration; see G. Rubens, William Richard Lethaby (The Architectural Press, 1986), 233-43.

4 C. Frayling, The Royal College of Art: One Hundred and Fifty Years of Art and Design (Hutchinson, 1987), 100.

5 A large proportion of these works are now held in the archives of Buckfast Abbey (Devon), while many others have been bequeathed to the V&A Museum.

6 See J.E. Edward’s brief, but important article on her contribution: ‘English Medieval Wall-Paintings; The Monica Bardswell Papers’, Archaeological Journal 143, no.1 (1986): 368–69.

7 E.W. Tristram, with W.G. Constable, English Medieval Wall Painting: The Twelfth Century (Pilgrim Trust, 1944); E.W. Tristram, with M. Bardswell, English Medieval Wall Painting: The Thirteenth Century (Pilgrim Trust, 1950); E.W. Tristram, with M. Bardswell and E.M. Tristram, eds., English Medieval Wall Painting of the Fourteenth Century (Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1955).

8 See his pamphlet, ‘Note on the uncovering and preservation of ancient mural paintings’, published by the V&A Museum, c.1926; also S. Cather & H. Howard, ‘The use of wax and wax-resin preservatives on English mediaeval wall paintings: rationale and consequences’, Studies in Conservation 31, no.1 (1986): 48-53.

9 The Church was technically exempt from the provisions of the Ancient Monuments Act of 1913; see F.C. Eeles, ‘The Care of English Churches’, Ancient Monuments Society NS 1 (1953): 21-40, who charts the creation of the Central Council for the Care of Churches (in 1917) and the emergence of Diocesan Advisory Committees in the 1930s, with a Cathedrals Advisory Committee following sometime after, in 1949.

10 See W.I Croome et al., The Conservation of English Wallpaintings, being a Report of a Committee set up by the Central Council for the Care of Churches and the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (Central Council for the Care of Churches, 1959), in which the further use of wax preservatives on wall paintings is specifically proscribed.

11 Croome, Conservation of English Wallpaintings, 12.

12 ‘Major survey of English medieval wall paintings’, Courtauld Press release, 30th April 1980.

13 The budget for the 3 years totalled £120,000, of which £96,000 were secured through grant funding, the remainder coming from departmental research funds. For an overview of the project, see E. Howe, ‘The Courtauld launches National Wall Paintings Survey Project’, in Iconnect Magazine 1 (Spring 2023): 8.

14 Panel members include Prof. Alixe Bovey (Dean & Deputy Director, The Courtauld), Tom Bilson (Head of Digital Media, The Courtauld), Tobit Curteis (Tobit Curteis Associates), Dr. John Goodall (Architectural editor, Country Life), Tracy Manning (Cathedral & Church Buildings Division, Church of England), the late Prof. Austin Nevin (Former Head of Conservation, The Courtauld), Lisa Redlinski (Head of Library Services, The Courtauld), Dr. Jane Spooner (Senior Lecturer in Wall Paintings, The Courtauld), and Sophie Stewart (English Heritage).

15 Aoife Stables and Florence Eccleston assisted the project lead, Emily Howe, from April to December 2022.

16 The categories used were as follows: conservation, correspondence, David Park notes, images, publications, and unpublished material.

17 An Epson Workforce DS-770 II scanner was used, following National Archive guidelines https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/information-management/manage-information/preserving-digital-records/digitisation/ (accessed 30/01/25).

18 A total of 33 individuals were invited to take part, including art historians, conservators and heritage professionals, with data received from 23 respondents.

19 The system comprises a Collections Management System coupled with a Digital Asset Management (DAM) platform; see https://www.vitec-memorix.com/en/solutions/memorix-maior/ (accessed 30/01/25).

20 See https://photocollections.courtauld.ac.uk/menu-item1/conway-library (accessed 30/01/25).

21 Over eighty percent of respondents to our questionnaire cited conservation documentation and historic images among the most valuable resources in the Survey, material that is rarely available through other channels.

22 On this volunteer initiative, set up by Tom Bilson, See https://courtauld.ac.uk/libraries/collections-and-image-libraries/image-libraries/volunteer-digitisation-project/ (accessed 30/01/25).

23 Detailed screening guidelines have been developed, for each of the different categories of material being digitised, and are available for consultation within the project archive.

24 Amongst which the Wellcome Collection’s Digital Library Project, Tate’s Archives and Access Project (2012-17) and the Courtauld’s own Conway & Witt Digitisation Project – see https://stacks.wellcomecollection.org/digitisation-strategy-2020-2025-c965dd77624f), https://www.tate.org.uk/about-us/projects/transforming-tate-britain-archives-access) and (https://photocollections.courtauld.ac.uk/copyright) respectively, accessed 30/01/25.

25 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode.en, accessed 30/01/25. Our licence agreement allows for the use of material for ‘non-profit academic publications and grant-funded conservation reports’.

26 https://photocollections.courtauld.ac.uk/disclaimer, accessed 30/01/25.

27 Statistical analysis of recently digitised material is, for example, helping us to map historic treatment practices such as the waxing of wall paintings (and subsequent efforts to remove it), investigations which have been supplemented by new scientific analysis of conservation coatings on historic wall painting samples in our own collection, undertaken in partnership with the University of Maastricht. We are working with Dr Caroline Bouvier and Prof Sebastiaan van Nuffel to undertake high resolution time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry (ToF-SIMS) analysis to identify and characterise organic conservation coatings (such as varnish, wax and soluble nylon) on paint samples from the Survey archive. For the technique see C. Bouvier, S. Van Nuffel, P. Walter, & A. Brunelle, ‘Time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry imaging in cultural heritage: A focus on old paintings’, Journal of Mass Spectrometry 57, no.1 (2002), https://doi.org/10.1002/jms.4803, accessed 30/01/25.

Bibliography

Bouvier, C., S. Van Nuffel, P. Walter & A. Brunelle, ‘Time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry imaging in cultural heritage: A focus on old paintings’, Journal of Mass Spectrometry 57, no.1 (2002), https://doi.org/10.1002/jms.4803.

Cather, S., ‘Assessing causes and mechanisms of detrimental change’, in Conserving the Painted Past: Developing Approaches to Wall Painting Conservation, edited by R. Gowing & A. Heritage. James & James, 2003.

Cather, S. & H. Howard, ‘The use of wax and wax-resin preservatives on English mediaeval wall paintings: rationale and consequences’, Studies in Conservation 31. no.1 (1986): 48-53.

Croome, W.I. et al., The Conservation of English Wallpaintings, being a Report of a Committee set up by the Central Council for the Care of Churches and the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings. Central Council for the Care of Churches, 1959.

Edwards, J.E., ‘English Medieval Wall-Paintings; The Monica Bardswell Papers’, Archaeological Journal, 143(1), 1986: 368–69.

Eeles, F.C., ‘The Care of English Churches’, Ancient Monuments Society NS 1 (1953): 21-40.

Frayling, C., The Royal College of Art: One Hundred and Fifty Years of Art and Design. Hutchinson, 1987.

Howe, E., ‘The Courtauld launches National Wall Paintings Survey Project’, Iconnect Magazine 1 (Spring 2023): 8.

Keyser, C.E., A List of Buildings in Great Britian and Ireland Having Mural and other Painted Decorations, 3rd edition. H.M. Stationary Office, 1883.

Rubens, G., William Richard Lethaby. The Architectural Press, 1986.

Tristram, E.W., Note on the uncovering and preservation of ancient mural paintings. V&A Museum, 1926.

Tristram, E.W., with W.G. Constable, English Medieval Wall Painting: The Twelfth Century. Pilgrim Trust, 1944.

Tristram, E.W., with M. Bardswell, English Medieval Wall Painting: The Thirteenth Century. Pilgrim Trust, 1950.

Tristram, E.W., with M. Bardswell and E.M. Tristram, eds., English Medieval Wall Painting of the Fourteenth Century. Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1955.