In a drawer in the stores of the British Museum’s Department of Britain, Europe, and Prehistory lies a tiny ivory carving rarely seen by the public. Small enough to be held in the palm of the hand, it is double-sided, displaying two intricately carved scenes from the Passion narrative: the Agony in the Garden of Gethsemane and the Pietà. The entire object is richly polychromed with details picked out in gilding, and four small holes are carved into the semicircular base.

A survey of the Courtauld Institute of Art’s Gothic Ivories Project database confirms that the combination of style, iconography, and extensive polychromy renders this carving unique among the roughly five thousand documented gothic ivory carvings.1 There are only four known ivory Pietàs, all of which are single-sided and stylistically dissimilar from this object. Likewise, the two extant Gethsemane fragments are single-sided relief carvings.2 One multisided statuette with devotional imagery survives at the Victoria and Albert Museum although with a different style and iconography.3 Each of these objects exemplifies the minimal polychromy typical of ivories of thirteenth- and fourteenth-century French origin. While the majority of extant gothic ivories were produced in Paris ca 1240-1330, the British Museum carving has been assigned a production date of ca 1420 and a location of ‘Germany: (South?)’.4

Very little is known about this object for two primary reasons. The first is common to almost all gothic ivories: the lack of information about the circumstances in which they were made and used, due to the dearth of surviving sources. The second reason is methodological: its singularity within the gothic ivory tradition has caused this object to slip through the cracks of traditional scholarship, which is traditionally structured around the subdivision of groups. The earliest existing reference to the British Museum ivory appears in the Ivories Notebook, English antiquarian William Maskell’s (1814-1890) handwritten catalogue of his extensive ivory collection acquired by the British Museum in 1856. Writing between 1854 and 1856, Maskell described this carving in one particularly short entry: ‘102. Statuette: Coloured:-’.5 With considerably longer entries for his numerous Parisian Virgin and Child groups and diptychs, Maskell’s description is emblematic of a methodology that values common types, and this ivory’s resistance to easy classification has affected its study since.6

For instance, in 1909, in what remains the only catalogue of the British Museum ivories, O. M. Dalton hierarchised the objects by type, declaring that ‘the most important of all ivory carvings are diptychs’, followed by statuettes, caskets, and crosiers.7 Unable to locate this object in any of these groups, he placed it within the miscellaneous category, ‘Carvings: Thirteenth to Fifteenth centuries’. Similarly, in Raymond Koechlin’s seminal Les Ivoires gothiques français (1924), the object is catalogued under ‘Piéces Isolées’, produced in ‘foreign’ (non-French) workshops of the later gothic period.8 Likely due to the authority of Koechlin’s methodology, the object has appeared in print only once in the last century—within the 2008 survey of Masterpieces of Medieval Art at the British Museum. In his short summary, J. Robinson frames the iconography within a private devotional context without detailing his reasons for this conclusion.9

In a departure from the taxonomy of established scholarship, this article will approach the British Museum ivory with the care and attention that its scale and detail demand. As our only evidence of its early history is the object itself, an analysis of material evidence, including iconography, configuration, and patterns of wear, is necessary to reconstruct its possible function and use. As it fails to find stylistic or iconographic affinity with other gothic ivories, the scope of study will include comparisons with works in other materials to begin identifying a production context. What emerges is a unique carving of exceptional quality, the two scenes working together to captivate the viewer in a moving rumination on life, death, and the importance of private prayer.

A Visual Description of the Ivory

The abundance of colour and detail relative to the size of this ivory is immediately striking. Every millimetre of the dentine has been carved to accommodate the two scenes, which have both been entirely polychromed. Robinson states that the polychromy is a later addition, which may have been applied over areas of original colouring, excluding Christ’s body, which was left white.10 However, three factors indicate that this painted layer is original: the discolouration fits known patterns of pigment deterioration, the detail and accuracy of the application correspond with the quality of the carving, and the extensive colouring is at odds with later restoration practices, namely the preference for ‘pure’ ivory that led to the stripping of polychromy in the nineteenth century.11 Paint was also lost through systematic casting during this period, and the peculiar style and iconography of this carving—at odds with the preference for Parisian types exemplified by Dalton’s prescribed hierarchy— likely saved it from this process.

The Gethsemane scene features a cavernous, rocky landscape of grooves carved deep into the ivory (Fig. 1). This landscape creates a two-tiered composition: Christ kneels atop a rocky overhang, beneath which the apostles sleep in three distinct niches. Saint John, distinguished by his short and gilded curls, occupies the left niche, his head resting on his left hand. Saint Peter occupies the centre niche, his left arm supporting his head while his right hand holds a sword. Saint James lies curled in the right niche. Above them, Christ kneels in prayer with an upward gaze, contrasting with the closed eyes of his companions; his voluminous blue drapery highlights his single exposed foot and the wound it bears. A small, discoloured hole in the top of the mound indicates the loss of an affixed metal chalice, a symbol habitually included in contemporary representations of this scene. The orange discolouration along the break provides evidence that Christ’s upper body was detached and subsequently reaffixed using an adhesive. The left side of Christ’s head is lost, revealing a flat area of exposed ivory. The polychromy has worn away to reveal patches of white in several areas, including the painted heads of the apostles, Peter’s sword, Christ’s exposed foot, and the edges of the drapery and landscape.

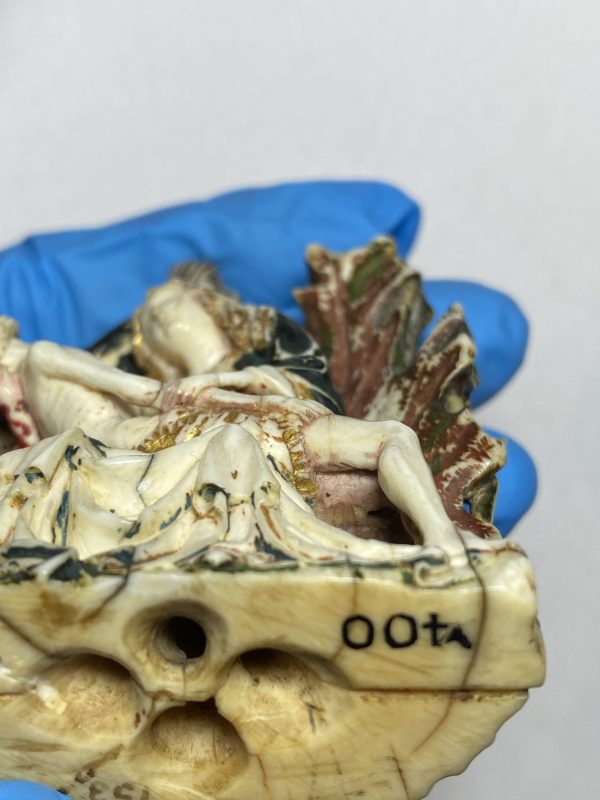

Turning the object around, the reverse of the Gethsemane creates an earthen-red backdrop that frames the Pietà, with small incisions in the exposed ivory marking areas where the material has been cut away (Fig. 2). The praying Christ is visible above the garden scene on the reverse, his head turned away from the viewer. The Virgin cradles the rigid body of her son across her knees, her right hand gently supporting his head while her left clutches his right arm. Christ’s face, beard, and hair are intricately carved, and he wears a stylised crown of thorns in a twisted band. His ribcage and collarbones have been carefully modelled to accentuate his fragility, echoed in the skeletal rendering of his hands and feet. His emaciated arm confronts the viewer at the centre of the composition, its entire circumference apparently grasped by the Virgin. This fragility is illusionistic: examination from below reveals that the arm is attached to the upper torso and leg, explaining its survival (Fig. 3). Small incisions indicate Christ’s wounds, which contain tiny flecks of red polychromy. The Virgin gazes with a grieved expression upon the upturned face of her son, her arms encircling him in a tender yet impassioned embrace. Her face and hands are rounded and youthful, contrasting with Christ’s skeletal form. Her veil is carved with delicate, ridged folds and bordered by a crimped, gilded edge that also appears on Christ’s loincloth. She wears a red underdress and a blue robe with a gilded hem which falls in U-shaped layers of drapery from her knees. The polychromy around the knees is considerably worn, revealing the white ivory beneath. The ivory of the Virgin’s face and Christ’s body is similarly exposed, and—contrary to Robinson’s observation—traces of pink colouring in the incisions of the Virgin’s hands and the underside of Christ’s legs reveal that the flesh of both figures was originally polychromed (Fig. 3).

The object’s semicircular base follows the growth rings of the ivory, which form thin cracks in the surface (Fig. 4). While the Gethsemane follows the natural curve of these rings, the cracks cut vertically up from the base into the Pietà and are clearly visible on Christ’s right foot and right arm (see Fig. 2). A small nail has been inserted beneath Christ’s foot, presumably to stabilise this area. The rings and curved shape indicate that the ivory was cut at a cross-section from the tapering end of the elephant tusk, requiring the removal of the outer cementum layer at the tip as well as the outer edges.12 The base itself features a cluster of four conical holes in a diamond configuration. A thin, indented ridge cuts horizontally along the sur- face, crossing the centre of the cluster. Together, these channels lead to a small cavity inside the object, although the channel of the largest hole continues further up into the interior.

Devotional Function of the Ivory

Taken together, the object’s dual iconography and the cluster of holes at its base has perplexed those attempting to establish its original function. In 1905, A. Maskell proposed that the object sat in the volute of a crosier.13 Four years later, Dalton suggested that the holes received a cord, allowing the carving to be worn like ‘a Japanese netsuke’.14 In 1924, Koechlin dismissed Maskell’s theory without offering an alternative, and no direct attempt to determine the object’s function has been made since.15

At first, Maskell’s theory appears plausible, given the dimensions of the object and its double-sided design. Yet the iconography is not mirrored in any crosiers of this period, which typically feature a Crucifixion with a Virgin and Child carved from two separate panels. Additionally, the object lacks the single, central dowel hole commonly used to fix carvings inside a volute.16 Instead, the distinctive configuration of the holes indicates that the carving was affixed to a bespoke support, possibly of a different material. The few examples of statuette bases available through the Gothic Ivories Project offer limited parallels. These usually display small, cylindrical dowel holes in sets of one or two, and none include an indented ridge. Such holes, positioned on the underside of single-sided subjects, would have enabled these carvings to sit on a simple base, or within a larger tableau structure.17 One Virgin and Child statuette displays an irregular group of five holes, although they are straight and do not link to form a single cavity.18 The only visible instance of a conical hole occurs in the base of a Virgin and Child carved from sperm whale ivory, where the shape of the cavity corresponds with the form of that material, rather than a specific system of attachment.19 By contrast, the holes and ridge in the base of the British Museum ivory indicate a deliberate attachment method which departed from standard techniques. While the dearth of comparative examples complicates the identification of an appendage type, close analysis of the object’s iconography, configuration, and patterns of wear can begin to offer insight into its original function and use.

As the two scenes of emotional anguish that bracket the Passion narrative, the Gethsemane and the Pietà evoke the act of private devotion in different ways. In the Gospels, the Agony in the Garden recounts Christ’s spiritual battle in the garden at the foot of the Mount of Olives the night before the Crucifixion, when he pleads with God before accepting his fate. The contrast between the tormented Christ and the oblivion of his disciples made depictions of Gethsemane a popular visual tool for the promotion of private prayer, particularly in fifteenth-century Germany, where large-scale groups in wood and stone were erected in cloisters and cemeteries to inspire contemplation throughout the year.20 In his influential Vita Christi, the German theologian Ludolph of Saxony (ca 1295-1378) frames the Gethsemane episode in pedagogical terms, underscoring the importance of seclusion to meditation by informing us that ‘if we wish to pray with devotion we should, like Christ, withdraw from the company of others and seek some solitary place’.21 The efficacy of private contemplation is reflected in the compositional layering of this carving, which juxtaposes the exposed and awake Christ with the sleeping apostles in their niches.

While the Gethsemane provides an archetypal image of prayer, the Pietà facilitates contemplation. The group does not appear in the Bible but emerged from the mystical tradition of Rhenish convents of the fourteenth century as an autonomous Andachtsbild, or imitatio image.22 The compositional isolation of the Pietà derives from the mystical belief that when the body of Christ was placed on the Virgin’s lap, she lost all sense of time and place. Particularly effective in sculptural renditions, this isolation throws the dualities of mother/son and living/dead into sharp relief and heightens the emotional import of the group. Simultaneously, the composition denotes a temporal proximity and a level of intimacy for the viewer. In her study of the Pietà and the beguines in the southern Low Countries, J. E. Ziegler describes the extra-liturgical relationship between the group and the viewer as ‘primarily a private and sensory one’, evoking ‘feelings of a most personal, inner sort’.23 The German mystic Heinrich Suso (ca 1295-1366) recounts the emotive power of the Andachtsbild, asking a Pietà Virgin to place the body of Christ ‘on the lap of my soul so that … I may be vouchsafed in a spiritual manner and in meditation that which befell you in a physical manner’.24 While Pietà statuettes were housed in a variety of public and private settings, including convents, churches, and pilgrimage oratories, the personal and bodily relationship described by Suso points to a function outside of the dictates of public religion.25 Notably, the German word for Pietà is Vesperbild, referencing the canonical hour traditionally reserved for private meditation on the Crucifixion. The British Museum ivory furthers this intimacy by reducing the Pietà to a scale that fits in the palm of the hand, necessitating close observation.

It should be noted that the Gethsemane and the Pietà both have eucharistic resonance. The chalice in the Gethsemane refers to Christ’s prayer ‘My Father, if it be possible, let this cup pass from me’ (Matthew 26:39), evoking the cup from which the disciples drank at the Last Supper. In the larger Pietà sculptures housed in churches during this period, Christ’s side wound could be carved deep enough to deposit the host during Good Friday mass.26 Although these associations raise the possibility of a liturgical function, the diminutive size and intricacy of this object align with the private devotional associations of the iconography. Furthermore, while the function of the Pietà as an Andachtsbild precedes its adaptation for liturgical use, the popularity of depictions of Gethsemane as a model for private prayer eclipses their eucharistic interpretation in Germany and the Netherlands during this period.27

Handling and Use

The ivory carving’s configuration further indicates a private devotional function. The semicircular base informs not only the shape of the object, but also the composition of the scenes and their relationship to one another. While the Gethsemane scene is carved into the rounded exterior of the tusk, the Pietà sits along the straight edge of the interior like a flat image. This reinforces the hierarchy between the two: the Gethsemane is instructive, representing the ‘how’ of prayer, while the detail and pathos of the Pietà provide the meditative substance. This relationship is confirmed by the continued visibility of the praying Christ from the Pietà side, upholding the centrality of the act of prayer to the experience of this object.

The interplay between the scenes is reinforced when the object is turned. Beginning at the left extremity of the Gethsemane and turning clockwise reveals the apostles in an unfolding narrative in which each is more deeply asleep than the first (Fig. 5). Simultaneously, Christ emerges gradually from behind the rock and what would once have been the chalice. Although the explicit violence of the Crucifixion is omitted from this object, the act of turning sequentially reveals two symbols that reference the violence to come. First appears the sword with which Peter cuts off the high priest’s servant’s ear, alluding to the violent chaos of Christ’s subsequent arrest. Turning again exposes the premature wound on the foot of the praying Christ, foreshadowing the Crucifixion.

Continuing to rotate the object, the viewer encounters the Pietà. While the iconography is devoid of narrative progression, the revelatory element is not wholly eliminated; Christ’s wounds are revealed in sequence—first the side, then the hand, and finally the feet, inviting contemplation of each in turn (Fig. 5). Simultaneously, the wounds have been carved for effective observation from a frontal perspective, reinforcing the importance of the direct gaze to the observation of the Pietà. While Christ’s side and hand wounds sit in the centre of the composition, the raised skin around the wounds in his feet ensures visibility in profile. Consequently, by linking the Gethsemane and the Pietà in a narrative sequence set in motion when turned, the object guides the viewer through the scene of prayer to the contemplative image beyond.

This act of turning and revealing is reminiscent of memento mori rosary beads, which are amongst the only other surviving double-sided gothic ivories.28 Designed to be rolled in the hand, these Janusian heads rotate to reveal a skull on the reverse of the portrait as a reminder of the inevitability of death. This ivory produces a similar effect when rotated: the pleading Christ gives way to reveal his inevitable sacrifice. As with the beads, the efficacy of the juxtaposition is heightened through compositional parallels—both pair an agonised party (Christ/the Virgin) with an unconscious party (the apostles/Christ), and both are bracketed by the wounds in Christ’s feet. The Pietà’s subversion of Virgin and Child iconography, which likewise evokes a memento mori, further strengthens this association. Like the rosary, the object’s small scale and rounded base invite the viewer to turn the carving around and contemplate each detail in a playful yet profound reflection on the dichotomy of life and death.29

That the object was indeed handled by its viewer is evidenced by the patterns of wear that have eroded the polychromy and the ivory beneath. These patterns are made up of distinct touchpoints, recognised indicators of ritualised physical engagement.30 On the Gethsemane side, the foreheads of each of the apostles, Peter’s sword, and Christ’s wounded foot have been repeatedly touched, degrading the polychromy and producing the glossy sheen that develops when ivory dentine is rubbed. It is possible that Christ’s head and the chalice also formed part of a haptic ritual, contributing to the loss of colour on these areas. The wound on Christ’s foot overlies the smoothed surface, suggesting that it may have been retouched at a later date.

On the Pietà side, the extensive areas of exposed ivory on the flesh of Christ and the Virgin’s face and drapery indicate more sustained tactile engagement. Raking light reveals that the minuscule incisions still visible on areas of Christ’s torso have been worn to a smooth surface on the Virgin’s left hand and knee, as well as Christ’s legs, right hand, and toes. This suggests a ritualised touching of the areas around Christ’s wounds, as well as a repeated stroking of Christ’s body and the Virgin’s knees. The touching of the latter corresponds with how the object sits in the hand; the curved shape fits snugly in the centre of the palm, and the thumb rests naturally on the worn central area. Holding the object in this way also corresponds with the wear on the edges of the Gethsemane landscape, which rests against the palm.

This act of holding and caressing may have been prompted by the Pietà, in which the Virgin encloses and caresses the body of Christ, structuring the response of the viewer in turn. Ziegler emphasises the primacy of touch to the observance of the Pietà, specifically its role in inducing an emotional ‘transference’ between beholder and object.31 Although the more extensive wear may have been sustained after the object was detached from its base, the repeated or intensified touching of specific narrative elements in the Gethsemane indicates an interplay between maker and viewer that invited physical engagement. This tactility likely formed part of a multisensory engagement with the object that included the recital of prayers. Prayers uttered before depictions of Gethsemane upheld its function as a devotional exemplar in this period. A fifteenth-century prayerbook in Dresden instructs its reader to pray as Christ prayed on the Mount of Olives while repeating his words: ‘Non sic ego volo, sed sic tu vis, pater’ (‘Not as I wish, but as you wish, Father’).32 Used in prayerbooks to demarcate the beginning of the final third of the Psalter, scenes of Gethsemane often appear in conjunction with the opening line ‘Hear, O Lord, my prayer: and let my cry come unto thee’ (Psalm 102:1).33 While the ivory Gethsemane may have prompted similar recitals, its unusual combination with the Pietà complicates the oral context as a whole. Notably, both groups were significant within rosary devotion, an early form of which developed in the Beguine communities of the Low Countries in the mid-thirteenth century.34 While the first meditation of the Passion cycle focused on the Agony in the Garden, the Pietà came to represent the culmination of the Seven Sorrows of the Virgin. A number of Pietà statuettes from this period sit on original bases which are studded with rosettes, prompting parallels to be drawn with rosary devotion.35 Understandings of the devotional efficacy of the Pietà developed within this context: a later fifteenth-century prayer book offers an indulgence for reciting the Pater noster, Ave Maria, and Credo while observing an image of the Pietà.36 It is possible that similar prayers were incorporated into the repeated touching of areas of this ivory, as part of a ritual reminiscent of the sequential, multisensorial nature of rosary devotion. Together, the patterns of wear and devotional context suggest that—rather than serving a liturgical function—this object was used in private contemplation, as part of an intimate, emotional ritual prompted by the careful configuration and emotive detail of the carving.

Materials, Trade, and Production

Investigating the function and use of this carving also requires an examination of its wider production context. The first piece of evidence to address is the age of the material. The ivory underwent carbon-14 analysis in 1995 and yielded a result of 1005 ± 50 BP, indicating a date range of 940-1170 CE with a probability of 95.4 per cent.37 While the date range confirms the carving’s authenticity, the result should not eclipse stylistic observations, as such readings only determine an estimated date of the death of the elephant, which may have preceded the object’s production by many years. It is conceivable that decades-old tusks were discovered in the African interior and sold, or that uncarved ivory was preserved in European treasuries.38 Furthermore, the fact that the reading was taken in the mid-1990s as an early venture into the technology also raises the possibility that, although broadly accurate, it may not be as reliable as readings taken today.39 Conversely, the dating underscores the singularity of the object; that it was selected for early testing suggests that its unique design raised doubts about its authenticity.

The disparity between the detected date of the material (ca 940-1170) and the style of carving (ca 1400-1450) reflects the irregularity of the ivory trade in the early fifteenth century, which restricted production to one-off pieces. The boom in ivory supply from around 1240 was disrupted a century later by the outbreak of the Black Death and the Hundred Years’ War and had diminished completely by 1380.40 By the early fifteenth century, workshop specialisation, determined largely by geographic availability, would have been inconceivable in ivory carving. Guild regulations reveal that Parisian workshops did not specialise in ivory even in the thirteenth century, when the supply of the material was at its height. Étienne de Boileau’s Livres des Métiers (ca 1268-1270) records only seven guilds that were legislated to work in ivory alongside other materials, including the guild of painters and image carvers, which was authorised to work in ‘all manner of wood, stone, bone, ivory, and all types of paint good and true’.41 This integration would have contributed to a synthesis of design across media which can be seen, for example, in the correspondence between Parisian Virgin and Child ivories and monumental stone sculpture.42 Produced during a time of scarcity, the British Museum ivory was likely a one-off carving made by a craftsman skilled in the use of other materials. It is therefore unsurprising that, while it struggles to be fruitfully compared with other gothic ivories, this object instead finds stylistic affinity with works in different media, specifically alabaster.

In his 1921 survey of German alabaster carvings, Georg Swarzenski cites this ivory as evidence of a single alabaster master working in Cologne in the second quarter of the fifteenth century. According to Swarzenski, this ‘Rhenish master’ designed and produced Gethsemane and Pietà groups that were emulated in alabaster workshops throughout Germany.43 Today, this craftsman is believed to have been active between 1420 and 1440 and is referred to as the Master of Rimini after an altarpiece attributed to him in the Italian town. Geographic localisation of the Rimini workshop remains uncertain; while stylistic observations indicate a southern Netherlandish influence, a recent study has revealed that the alabaster used is exclusively of Franconian (northern Bavarian) origin.,44

Characterised by the intricate detail, linear style, and emotive power of their designs, works associated with the Rimini workshop exhibit strong stylistic parallels with the British Museum ivory. Swarzenski attributes nine alabaster carvings of Gethsemane to the Rimini circle, describing the majority as ‘small’ and ‘almost round’.45 The correspondence between these alabasters and the ivory is striking: they each display variants of the ridged landscape, with the praying Christ placed above and the apostles arranged in three niches below.46 Although the location of most of these carvings is now unknown, one is in the collection of the Ashmolean Museum (Fig. 6). Measuring 17.9 by 19 centimetres, this rectangular relief unites Christ’s Agony and Arrest in a single composition.47 Occupying the lower half of the relief, this Gethsemane shares a number of similarities with the British Museum carving. A stylised rocky landscape forms two distinct levels and three individual niches. Christ prays above the apostles in profile, and the base of a damaged chalice sits atop the rocky outcrop before him. Peter holds a sword of identical style to that depicted in the ivory. These similarities are further reinforced by material examination, which has revealed a rich polychromy programme: the landscape was painted green, and the figures were at least partially—if not entirely—polychromed.48

Numerous alabaster Pietàs have been attributed to the Rimini circle. Although the group displays differences in technical execution, the style, composition, and scale (40 to 60 centimetres high) are broadly consistent—as pictured in Swarzenski’s publication (Fig. 7).49 In all models, the dead Christ lies with his head to the Virgin’s right, his body supported by her knees from which drapery falls in U-shaped folds. The round-faced Virgins all wear ridged veils with crimped borders and capacious robes, and in every group Christ’s crown of thorns is rendered as a stylised twisted band. Emotional intensity is a common feature, with consistent emphasis on the contrast between the youthful Virgin and the emaciated, rigid body of her son. This repetition reflects the popularity of the model and its efficacy in stimulating contemplation. However, the slight variations of detail in each Pietà, relating largely to the angle of Christ’s body and the positioning of the hands, show that these carvings were not produced by rote.50

Among all those attributed to the Rimini workshop, the so-called Lorch Pietà holds the closest stylistic affinity to the British Museum group (Fig. 8).51 The near-identical composition and modelling, including the position of the Virgin’s hands and Christ’s feet, which curl over the edge of the ground, are unparalleled within the Rimini corpus. This correspondence, combined with the slight simplification of the drapery in the ivory, raises the possibility that the British Museum ivory is a derivative—or even a copy—of the Lorch model. Additionally, traces of polychromy on the alabaster reveal the original colouring, mirrored in the ivory; the Lorch Virgin originally wore a blue robe and red underdress, Christ’s loincloth was gilded, and his wounds were painted red.,52 Although depictions of Gethsemane and the Pietà were being produced in a range of materials at this time, the Rimini sculptures bear the closest resemblance to this carving.53 Alabaster and ivory had close material and spiritual associations in the gothic period, stemming from their whiteness and the fact that, unlike stone, both were warm to the touch. While alabaster could be worked on a larger scale, both materials were used to make similar objects, which are often listed together in inventories; for instance, the inventory of Margaret of Flanders (d. 1405) records an ivory depicting the Nativity and Circumcision of Christ alongside three alabaster Virgin and Child groups.54 It has been suggested that during the ivory shortage of the early fifteenth century, there was a ‘degree of interchangeability and equivalence’ between the two materials that led to the use of alabaster as a substitute.55 Yet by emulating Rimini compositions, the British Museum ivory appears to invert this pattern. It is plausible that the creator of this object, a craftsman likely attuned to the associations between the two materials, sought to recreate and combine two alabaster designs at a scale impossible in that medium. While works attributed to the Rimini circle are renowned for their detail, the supple quality of dentine enables an even greater level of intricacy. Here, the small piece of ivory has been utilised to its fullest: to enhance the allure for the viewer, heighten the emotive import of the object, and structure devotional engagement.

Three additional fifteenth-century ivories have been stylistically linked to the Rimini corpus: a statuette of Saint Christopher, a figurine of Saint Jerome, and a pendant displaying the Coronation of the Virgin.56 The southern Netherlands, and specifically Bruges, has been suggested as the geographic location for these carvings for three reasons: its prominence as a trading hub, its repute as a production centre for exclusive devotional objects, and its identification as the assumed location of the Rimini workshop.57 While the recent discovery of the alabaster’s Franconian origin complicates this theory, the existence of other ivories stylistically similar to the British Museum carving signifies a market for objects carved in the immediate milieu of the Rimini workshop.58 Extant carvings attest to the widespread popularity of specific motifs, and, as its name indicates, the workshop produced sculptures for export across Europe. These included representations of the Pietà like the Madonna dell’Acqua (ca 1430) in Rimini, demonstrating that demand for groups in this style extended beyond northern Europe by the second quarter of the fifteenth century. Although this could indicate that the British Museum ivory was made for an Italian patron, its close affinity with the Lorch Pietà points to a northern European owner. This is supported by the distinctions in the use of polychromy: while works in Rimini commissioned by Italian patrons display restrained polychromy, southern Netherlandish and German alabasters, including the Lorch Pietà, frequently exhibit the kind of extensive colouring seen on the British Museum ivory under discussion here.59

Approaching this ivory through visual analysis and cross-material comparison has helped to build a picture of its early function and use. Close examination of the carving revealed that the scenes of Gethsemane and the Pietà work together in a narrative reflection on the importance of private contemplation. These findings correspond with the visible patterns of wear, suggesting that the object was repeatedly and ritualistically handled. Stylistic parallels with works from the Rimini circle situate the object within a wider northern European carving tradition that prized extreme detail, while the reduced scale demonstrates a reimagining of alabaster compositions at a minuscule level. Together, these findings indicate that this statuette functioned as an aid to private contemplation, produced as a one-off piece during a time of ivory scarcity.

One key question remains: to what was the carving affixed? Seemingly unique among gothic ivories, the shape and configuration of the holes in the base indicate a more complex support than the standard bases of Virgin and Child statuettes with single, straight dowel holes. Despite this singularity, three possible characteristics of the appendage can be sketched out. First, the ivory’s scale, detail, and configuration suggest a small base that placed the object centre stage, enabling close observation and tactile engagement. This excludes the possibility that the carving formed part of a larger ensemble or was affixed to a functional liturgical object like a crozier. Like memento mori rosary beads—or even a netsuke—the holes could instead suggest a mobile function which allowed the carving to be turned and the narrative elements set in motion.

Second, the ivory’s affinity with Rimini works raises possibilities about the embellishment of this base, which may have echoed that of the Lorch Pietà. Combining chamfered edges with an open latticework design of gothic tracery studded with rosettes, this design is seen in other alabaster statuettes associated with the Rimini circle, as well as an ivory polyptych (ca 1450-1500) in Bruges.60 In addition to the devotional context of the rosary, the rose acted as a significant explanatory metaphor for the Passion—the beauty of the flower, its blood-red petals, and its sharp thorns encapsulating the contradictory ‘sweet sorrow’ of Christ’s sacrifice.61 A number of mystical writings conceptualise Christ’s wounds using rose imagery, with the Nürnberger Garten (ca 1400-1450) describing the ‘beautiful red roses of his holy wounds’.62 Relevant to conceptions of both the Agony in the Garden and the Pietà, these spiritual associations would have accentuated the emotive power of their depiction in the ivory without detracting from the object itself.

Third, extant composite ivories and evidence from inventories raise the possibility that the base was made of a different material.63 The collections of Charles V of France (1338-1380), for instance, contained ivory statuettes mounted on bases of ebony and silver.64 That this was already a composite object is evidenced by the discoloured hole beside the praying Christ, indicating the presence of a metal chalice. While the lack of discolouration around the four holes suggests that wooden dowels were inserted, the base itself was likely made from, or incorporated, precious metals. This would have increased the likelihood that it was sold on or melted down, accounting for its loss.

This study calls for a broader reconsideration of objects that fall outside the conventional taxonomies of gothic ivory scholarship. Employing careful observation and handling as a methodology can reveal crucial information that is often overlooked in single-material surveys in which objects are classified strictly by type. In the case of the British Museum ivory, this includes the context and quality of its production, the ingenuity of its configuration, and how these work together to elicit an intimate, emotive response from the viewer—traces of which can be found in the marks on its surface. More broadly, these findings demonstrate that attending to private devotional objects with the same care and consideration they were originally designed to receive can shed light on their production and function in the late medieval period.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the staff at the British Museum Archive and Study Room for their help and guidance in investigating this object and its provenance. I am especially grateful to Naomi Speakman, Sarah Guérin, and Kim Woods for offering their respective expertise in ivory and alabaster. My greatest thanks go to Susie Nash for introducing me to this wonderful object.

Citations

[1] ‘Gothic Ivories Project at The Courtauld Institute of Art, London’, accessed 18 April 2025.

[2] For Pietà examples: D. Gaborit-Chopin, Ivoires du Moyen Age (Office de Livre, 1978), no. 245; R. Koechlin, Les ivoires gothiques français (A. Picard, 1924), vol. 1, 345, 347; vol. 2, no. 969. For Gethsemane examples: Koechlin, Les ivoires gothiques français, vol. 1, 262, 288; vol. 2, no. 735.

[3] P. Williamson and G. Davies, Medieval Ivory Carvings 1200-1550 (V&A Publishing, 2014), no. 189.

[4] The British Museum, ‘Sculpture’, 1856, 0623.153. Accessed 30 March 2025.

[5] W. Maskell, Ivories Notebook, f. 23v. London, The British Museum, Department of Britain, Europe and Prehistory. For discussion of the Notebook, see N. Speakman, ‘“A Great Harvest”: The Acquisition of William Maskell’s Ivory Collection by The British Museum’, in Gothic Ivory Sculpture: Content and Context, ed. C. Yvard, E. Antonine-König, J. Levy-Hinstin (The Courtauld Institute of Art, 2017), 117-199.

[6] For a recent overview of ivory scholar- ship, see G. Davies, S. Guérin, ‘Introduction:

New Work on Old Bones’, The Sculpture Journal 23, no. 1 (2012): 7-12. For all mentions of this object: A. Maskell, Ivories: The Connoisseur’s Library (Methuen,

1905), 205; O. M. Dalton, Catalogue of the Ivory Carvings of the Christian Era in the British Museum (British Museum Press,

1909), no. 400; G. Swarzenski, ‘Deutsche Alabasterplastik des 15 Jahrhunderts’, Staedel Jahrbuch 1, no. 1 (1921): 180-181; Koechlin, Les Ivoires gothiques français, vol. 1, 347-348; vol. 2, no. 975; J. Robinson, Masterpieces of Medieval Art (British Museum Press, 2008), 44.

[7] Dalton, Catalogue, xix.

[8] Koechlin, Les Ivoires gothiques français, vol. 1, no. 975.

[9] Robinson, Masterpieces of Medieval Art, 44.

[10] Robinson, Masterpieces of Medieval Art, 44.

[11] For the ‘white ivory’ trend, see D. Gaborit-Chopin, ‘The Polychrome Deco- ration of Gothic Ivories’, in Images in Ivory: Precious Objects of the Gothic Age, ed. P. Barnet, (Princeton University Press, 1997), 49.

[12] S. M. Guérin, Gothic Ivories: Calouste Gulbenkian Museum (Scala Arts & Heritage Publishers Ltd, 2015), 45.

[13] Maskell, Ivories, 205

[14] Dalton, Catalogue, no. 400.

[15] Koechlin, Les ivoires gothiques français, vol. 2, no. 975; Robinson, Masterpieces of Medieval Art, 44.

[16] I thank Sarah Guérin for this insight.

[17] For a statuette fixed within a larger structure using a dowel, see Koechlin, Les Ivoires gothiques français, vol. 1, no. 948.

[18] Paris, Musée de Cluny—Musée National du Moyen Âge, Cl. 21531.

[19] Madrid, Instituto Valencia de Don Juan, Inv. I. 4846.

[20] J. Hamburger, Nuns as Artists: The Visual Culture of a Medieval Convent (University of California Press, 1997), 85; J. Warren, Medieval and Renaissance Sculpture in the Ashmolean Museum (Ashmolean Museum Press, 2014) vol. 2, 638.

[21] Ludolph of Saxony, The Life of Jesus Christ, part. 2, vol. 2, trans. M. T. Walsh (Liturgical Press, 2021), 28.

[22] J. E. Ziegler, Sculpture of Compassion: The Pietà and the Beguines in the Southern Low Countries c. 1300-c. 1600 (Institut Historique Beige de Rome, 1992), 28.

[23] Ziegler, Sculpture of Compassion, 15.

[24] Translated in H. van Os, The Art of Devotion in the Late Middle Ages in Europe, 1300-1500 (Merrel Holberton, 1994), 104.

[25] For the function and display of Pietà sculptures, see Ziegler, Sculpture of Compassion, 127-128, 155-160.

[26] P. Williamson, Northern Gothic Sculpture 1200-1450 (V&A Publishing, 1988), 142.

[27] For the importance of depictions of Gethsemane in structuring private devotion, see Hamburger, Nuns as Artists, 80-100.

[28] S. Perkinson, ‘Anatomical Impulses in Sixteenth-Century Memento Mori Ivories’, in Gothic Ivory Sculpture, 76-92.

[29] For devotional ‘play’, see F. Scholten, ‘Scale, Prayer and Play’, in Small Wonders: Late Gothic Boxwood Micro-Carvings from the Low Countries, ed. F. Scholten, et al. (nai010 Publishers/Rijksmuseum, 2016), 171-210.

[30] For touch as methodology, see P. Dent, Sculpture and Touch (Ashgate, 2014). For touch in medieval devotional practice, see K. M. Rudy, Touching Parchment: How Medieval Users Rubbed, Handled, and Kissed Their Manuscripts. Volume 2: Social Encounters with the Book (Open Book Publishers, 2024). For analysis of ivory handling, see A. Cutler, The Hand of the Master: Craftsmanship, Ivory, and Society in Byzantium (9th-11th Centuries) (Princeton University Press, 1994), 23-25, 29.

[31] Ziegler, Sculpture of Compassion, 171.

[32] Dresden, Kupferstichkabinett der Staatlichen Kunstsammlungen Hs. A 7Ia, fols. 7v-9v; described in Hamburger, Nuns as Artists, 92.

[33] Hamburger, Nuns as Artists, 80.

[34] A. Winston-Allen, Stories of the Rose: The Making of the Rosary in the Middle Ages (Pennsylvania State University Press, 1997), 15.

[35] For rosette bases, see Van Os, The Art of Devotion, no. 31; Hamburger, Nuns as Artists, Fig. 55 and Fig. 56; Gothic:

Architecture, Sculpture, Painting, ed. R. Toman (H. F. Ullmann, 2010), 352. The link to rosary devotion is made in van Os, The Art of Devotion, 104.

[36] K. Kamerick, Popular Piety and Art in the Late Middle Ages: Image Worship and Idolatry in England 1350-1500 (Palgrave, 2002), 172- 173, Fig. 6.5.

[37] Carbon-14 analysis undertaken in 1995 by Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit (ref: OxA-5787).

[38] I thank Sarah Guérin for this insight. For a technical discussion of carbon dating, see S. M. Guérin,

‘Reviewed Work(s): Medieval Ivory Carvings, 1200-1550 by Paul Williamson, Glyn Davies, James Stevenson

and Christine Smith’, The Burlington Magazine 156, no. 340 (2014): 757-758.

[39] I thank Naomi Speakman for these insights. For technical issues with carbon dating, see S. M. Guérin, ‘The Wyvern Collection: Medieval and Later Ivory Carvings and Small Sculpture’, The Burlington Magazine 162, no. 1412 (2020): 1000.

[40] For the ivory trade, see S. M. Guérin, ‘Avorio d’ogni ragione: The Supply of Elephant Ivory to Northern Europe in the Gothic Era’, Journal of Medieval History 36, no. 2 (2010): 156-174.

[41] Quoted Guérin, Gothic Ivories, 42.

[42] Six extant Virgin and Child statuettes are modelled on the 1240 trumeau of the north portal of Notre Dame. R. H. Randall, The Golden Age of Ivory: Gothic Ivory Carvings in North American Collections (Hudson Hills Press Inc, 1993), 10.

[43] Swarzenski, ‘Deutsche Alabasterplastik’, 186.

[44] For a summary of previous scholarship and current alabaster research, see W. Kloppmann et al. ‘A Pan-European Art Trade in the Late Middle Ages: Isotopic Evidence on the Master of Rimini Enigma’, PLOS ONE 17, no. 4 (2022), 1-17.

[45] Swarzenski, ‘Deutsche Alabasterplastik’, 120.

[46] Swarzenski, ‘Deutsche Alabasterplastik’, no. 60, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 87, 89.

[47] Warren, Medieval and Renaissance Sculpture, no. 202.

[48] K. Woods, Cut in Alabaster: A Material of Sculpture and Its European Traditions 1330-1530 (Harvey Miller 2018), 152.

[49] Swarzenski, ‘Deutsche Alabasterplastik’, no. 96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101; Williamson, Northern Gothic Sculpture, 54; R. Marks et al. The Burrell Collection (William Collins Sons, 1983), 92, Fig. 12.

[50] Woods, Cut in Alabaster, 102.

[51] Van Os, The Art of Devotion, no. 31; Woods, Cut in Alabaster, 40-41.

[52] Woods, Cut in Alabaster, 41.

[53] For Bohemian Pietàs in stone and wood, see L. Kvapilova, Vesperbilder in Bayern von 1380 bis 1430 zwischen Import und einheimischer Produktion (Michael Imhof Verlag, 2017). For terracotta works, see J. von Fircks, B. Buczynski, Die Lorcher Kreuztragung: Tradition und Experiment in der mittelrheinischen Tonplastik um 1400 (Michael Imhof Verlag, 2015).

[54] Woods, Cut in Alabaster, 150.

[55] Woods, Cut in Alabaster, 150.

[56] I. Reesing, ‘From Ivory to Pipeclay: The Reproduction of Late Medieval Sculpture in the Low Countries’, Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek (NKJ) / Netherlands Yearbook for History of Art 67 (2017): 266.

[57] Reesing, ‘From Ivory to Pipeclay’, 266-267; F. Scholten, ‘Acquisitions: Sculpture’, The Rijksmuseum Bulletin 62, 3 (2014): 289.

[58] W. Kloppmann et al. ‘A Pan-European Art Trade in the Late Middle Ages’, 1-17.

[59] Woods, Cut in Alabaster, 40.

[60] Bruges, Museums Bruges, O.SJ0296. VI; Bruges, Museums Bruges, O.SJO221.VIII.

[61] Hamburger, Nuns as Artists, 63.

[62] Winston-Allen, Stories of the Rose, 98.

[63] W. Wixom, ‘Medieval Sculpture at The Cloisters’, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 46, no. 3 (1988-1989): 61.

[64] S. M. Guérin, French Gothic Ivories: Material Theologies and the Sculptor’s Craft (Cambridge University Press, 2022), 271, 273.