In The Squid and the Whale (Fig. 1, 2017), the American-born and London-based contemporary figurative painter Chantal Joffe stages a quietly arresting scene of maternal intimacy. Despite the composition’s softness in both form and affect, the fluid brushwork and restrained pastel palette quickly reveal a more tense emotional undercurrent. The painting conveys fragility, as though the image might collapse under the weight of its own emotional charge. At first glance, it is a domestic scene like any other: two figures, mother and daughter, share the side of a bed. Something is off-balance, though. The mother, partially unclothed, is hunched and inward-turning. Her slumping body tapers into a small, withdrawn head. Behind her, the daughter is upright, her posture tense, her gaze steady and unflinching. The compositional asymmetry is more than visual; it marks a subtle inversion of roles. Though smaller in scale, the child appears momentarily enlarged, assuming a symbolic verticality as the maternal figure leans, perhaps for the first time, into her. Taking the moment of asymmetry and tension as its point of departure, this article focuses on The Squid and the Whale to examine the shifting mother-daughter dynamic as revealed through the temporality of the child’s gaze and the layered references to literature, popular culture, and mythology that clarify this transition taking place.

The Squid and the Whale reflects Joffe’s broader practice, which prominently features the female figure. Among the most frequent subjects is her daughter Esme (born in 2004), who has sat for her repeatedly since childhood, and whose image recurs throughout Joffe’s work in tandem with self-portraits. This repeated doubling of mother and daughter makes The Squid and the Whale a particularly compelling example through which to consider the tensions between intimacy and separation that animate Joffe’s practice. While this dynamic is especially pronounced in depictions of her immediate circle, which includes mothers, daughters, and close friends, it also extends to writers, models, and sex workers. This marks a shift from earlier, more overtly pornographic imagery to scenes centred on motherhood. An occasional male sitter also appears in a largely female cast. Joffe frequently returns to the nude figure not merely as a formal exercise, but as a critical site through which to explore the entanglements of subjectivity and relationality. She has established a reputation for working at a monumental scale, both in the dimensions of her paintings and in their compositional logic. Her pared-back brushwork conveys time, transition, intimacy, fragility, and ageing, and its deliberately unpolished finish privileges emotional immediacy over technical refinement.

Joffe’s influences and choice of subjects reflects a sustained engagement with predominantly, but not exclusively, female artists and thinkers who have challenged dominant representations of female identity and embodiment. She draws on the work of Alice Neel, Diane Arbus, and Lucian Freud, valuing their candid attention to the ageing female body and its emotional complexity, as well as their resistance to aesthetic conventions. From an early stage, Joffe was interested in Freud’s attentiveness to paint as a material presence in the finished image, his sense of interiority, and his rendering of the body as ‘almost like a landscape’. From Neel, she absorbed a different lesson: a way of depicting the ageing female body as subtly ‘melting’.1 Both the landscape-like body and the gently dissolving one re-emerge in The Squid and the Whale series through its expansive scale and atmospheric softness. Joffe’s portraits also draw energy from the underlying disquiet that runs through early twentieth-century figurative painting, especially the German New Objectivity artists such as Max Beckmann, whose work carries a charged psychological atmosphere. This interest extends to later American painters like Alex Katz, whose restrained surfaces harbour a subtle emotional complexity that resonates with Joffe’s own approach. In The Squid and the Whale, this lineage is visible in the quiet psychological tension that permeates the still poses, where a barely perceptible tilt of the shoulder or shift in weight carries the muted strain of a relationship in transition. Joffe’s sources are not limited to painters. Her references include figures such as Sylvia Plath, Francesca Woodman, and Susan Sontag; women who blurred the line between art and life and complicated the relation between self and other. Her portraits of Hannah Arendt, Claude Cahun, Anna Freud, Paula Modersohn-Becker, Anne Sexton, Sontag, Nancy Spero, Gertrude Stein, and Alice B. Toklas, among others, underscore her commitment to portraying women who resisted conventional ideals of womanhood and whose lives were marked with both intellectual force and emotional intensity.

Joffe’s focus on exploring motherhood positions her within a broader feminist art-historical discourse that has, only in recent years, begun to theorise maternal experience with critical attention. Early feminist movements of the 1960s were instrumental in challenging binary

constructions of gender and the subjugation of women, but often failed to accord motherhood a central role in their critiques. It was not until the 1976 landmark publications by Adrienne Rich and Jane Lazarre that the ideological figure of mother was the focus of critical analysis.2 These texts paved the way for subsequent collections that expanded feminist explorations of maternal identity.3 Much has thus changed in the art fields since Lucy Lippard reflected in 1976 on the scarcity of maternal imagery in women’s art, with a substantial body of scholarship now addressing the expanded depictions of motherhood as a complex and often ambivalent subject in contemporary practice.4 With this growing body of literature, it is now possible to trace the origins of western contemporary representations of motherhood that finds their modern precursors in figures such as Mary Cassatt, Berthe Morisot, Käthe Kollwitz, and Modersohn-Becker.

There is increasing popular and curatorial interest in Joffe, but critical scholarship remains limited.5 Her explorations of motherhood and ageing are frequently overshadowed by more canonical figures such as Louise Bourgeois or Neel. However, Joffe’s rising visibility in corrective art histories—which seek to reframe the male-dominated canon by centring female artists—shows her relevance to broader re-evaluations of women’s contributions to art. Her focus on the everyday lives of women aligns her in particular with the tradition of Cassatt and Morisot.6 She has also been discussed in relation to Modersohn-Becker and the lineage of women who depict other women in ways that resist patriarchal constructions of the gaze. As Dorothy Price argues, Joffe’s focus on bodily vulnerability and the rhythm of change is part of the tradition of rejecting the idealised nude and replacing it with a self-aware and emotionally complex female gaze.7 This principle extends to the way Joffe reworked the misogynistic undertones of Edgar Degas’ distorted nude bathers by redirecting the terms of looking towards the self and one’s own body, while also unsettling the assumed roles between artist and model.8 She is also read within the legacy of Freud’s unflinching depictions of an ‘unravelled figure’, though she simultaneously undermines the male gaze by disrupting gendered conventions.9 On the other hand, philosophers of contemporary art have read her practice as part of a broader return to figuration following the fragmentation of the historical avant-gardes.10 Long-term collaborators and friends Gemma Blackshaw, Olivia Laing, and Price offer the most detailed engagement with her practice and often foreground the maternal as a deeply personal and interior experience.11

This article begins with the centrality of motherhood in Joffe’s work. It incorporates the notion of being mother before shifting to consider seeing mother, asking how this transition is expressed via the embodied temporality of the mother-child relationship. In the absence of sustained academic scholarship on Joffe, the article brings together curatorial insights, published interviews, and new material from original conversations with the artist and her circle, integrating these with close visual analysis grounded in feminist theories of temporal embodiment and maternal subjectivity. Focusing on The Squid and the Whale, the essay argues that Joffe’s painting charts a soft but decisive transition in the mother-daughter dynamic, articulated through references to religious mythology, literature, and popular culture. In doing so, the article offers a new way of reading Joffe’s figurative practice—through the evolving gaze of the child and shifts in the filial relationship—and thus contributes to broader feminist discussions on ageing, separation, and the affective labour of motherhood.

Whales, Squids, and the Softened Scene of Seperation

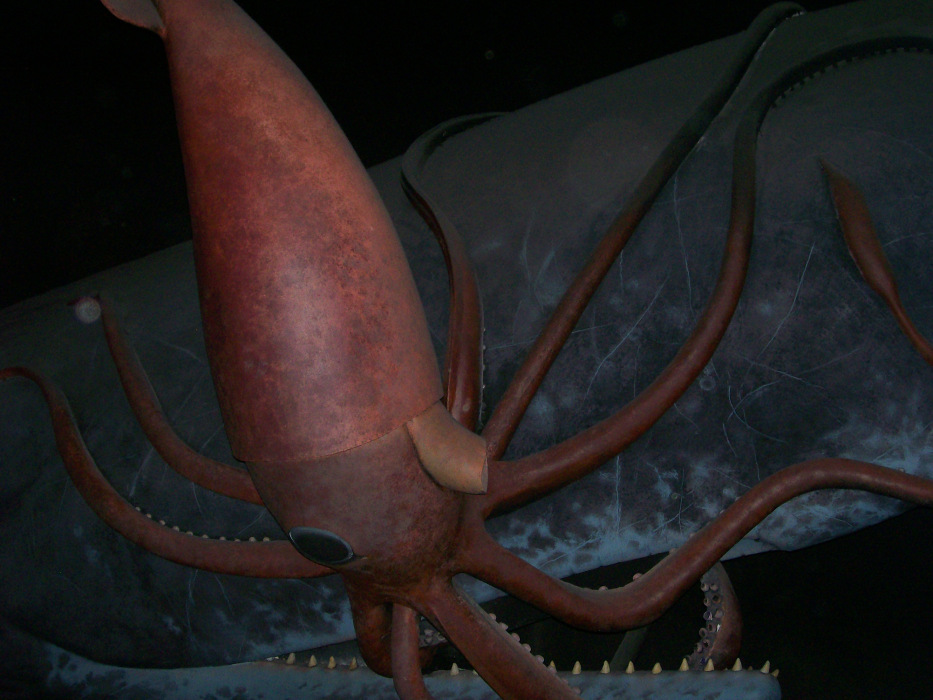

Joffe’s The Squid and the Whale engages a rich intertextual field of literary, cinematic, and museological references to depict the emotional tension of the mother-child relationship. Titled after Noah Baumbach’s film The Squid and the Whale (2005), which recounts an acrimonious divorce through the eyes of two adolescent brothers, Joffe’s painting studies family breakdowns.12 In a climactic scene of the film, the elder brother, Walt Berkman, is in a therapy session when he recalls his childhood visits to the American Museum of Natural History. He remembers shielding his eyes from the imposing diorama (Fig. 2) of a squid battling a sperm whale, a scene he once found frightening. His mother later described the diorama to him in a soothing manner, which he interpreted as emblematic of her emotional presence and a stark contrast to his father’s emotional absence. Walt later returns to the museum and confronts the display directly. In the entangled, soft-bodied yet monstrous creatures, he recognises a conflict without a clear victor, providing the film’s closing scene with its final metaphor for his parents’ divorce. Joffe painted The Squid and the Whale during the period of her own separation from Esme’s father. However, the fraught dynamic of Baumbach’s mother and father characters is shifted in Joffe’s work to a mother-daughter relationship. It is further softened through pastel tones, blurred edges, and a visual language that casts Joffe as the sole protector. Her form is monumental in scale but rendered with striking softness and vulnerability.

The painting captures a subtle but significant break. It marks both the changing emotional and artistic relationship between mother and daughter and visually traces Esme’s gradual departure from the frame that once contained her. There is an ambiguity to the scene heightened by the murky grey backdrop, which refuses to anchor the figures in a clear setting and instead wraps them in an indeterminate space. Temporal ruptures and shifts remain indistinct; Joffe seems to hover in a state of uneasy suspension, capturing a break that unfolds gradually, ambiguously, and with a muted softness. The atmosphere is tense, cold, and persistently unsettled. Joffe’s brushstrokes possess a striking duality: they appear dry, as though the paint cannot fully satisfy the breadth of the brush, while elsewhere they drip down the canvas, producing an unstable interplay of surfaces that mirrors the precarious dynamic between mother and daughter. As Price notes, Esme holds a central position in both Joffe’s personal life and artistic practice:

Esme has left home now and is at university—there was a period when Esme didn’t want to sit for her anymore so they had to go through that. Esme will sometimes now sit for her but not always. It’s about renegotiating their relationship in many ways.13

This renegotiation described here is legible in Esme’s more tentative placement in the composition, which signals an adjustment in how she places herself within the relational field of the painting. For Esme, the complexities of their bond are heightened by the fact that its changes are documented and circulated through her mother’s paintings. As Joffe reflects:

Esme’s relationship to the paintings of her has changed a lot over time. She said to me the other day that she realised that when she was remembering her own childhood she realised that the images she was picturing were the paintings I had made of her, and that was a strange realisation.14

Her remark points to a process in which representation begins to overwrite recollection itself, turning the painting not only into a record but into an active agent in how relationships are understood. This slippage between the fragility of memory and image resonates with Kathleen Woodward’s reflections on ageing and temporality, in which she argues that psychic life unfolds across shifting planes of past and future:

In psychic time we move backward and forward between the future and the past. We project ourselves into the future (although often not very far into the future consciously), and we bring our identifications from the past with us into those imagined futures’.15

The temporal structure of Joffe’s mother-daughter scenes operates in a similar register, suspended between remembrance and anticipation. Within this framework, the child becomes a carrier of temporal complexity; as Woodward notes elsewhere, children ‘play into the future as well as work through and out of the past’.16 In The Squid and the Whale, this dynamic materialises in Esme’s upright pose, which signals not only a moment of present withdrawal but also the forward motion of a future moving beyond the maternal field.

To articulate this shift in the mother-daughter dynamic, Joffe’s symbolic vocabulary engages not only with contemporary film but also with the literary and mythological traditions that shape Anglo-American cultural memory, such as the iconic whale and squid diorama at the Museum of Natural History. Positioning herself as the cumbersome, wounded whale, Joffe casts her daughter as the agile and elusive squid. In the diorama, the squid appears smaller as it clings to the whale, but it is still able to leave lasting marks. Both soft-bodied creatures bear the traces of their violent encounter, registering the force of physical and emotional proximity. Suspended dramatically in mid-air, the display was introduced during the 2003 revamp of the Hall of Ocean Life.

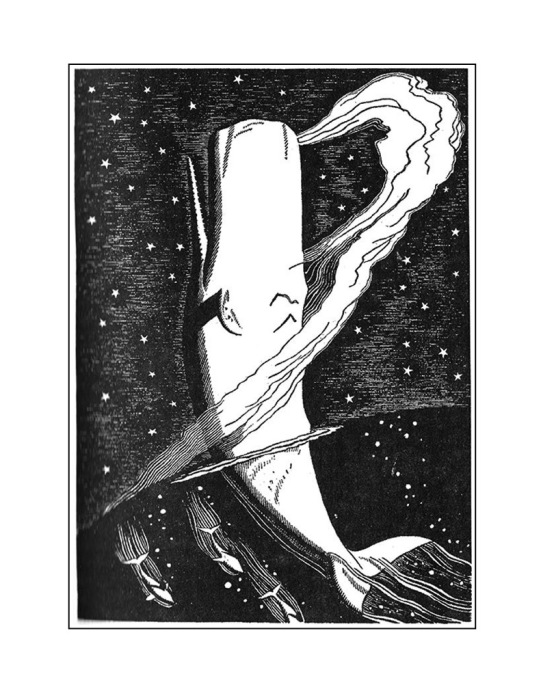

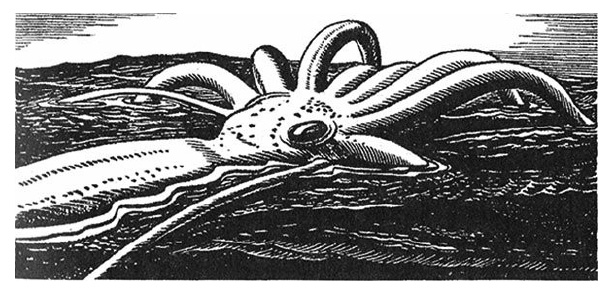

While grounded in scientific knowledge of deep-sea fauna, the reference also captures the viewer’s imagination by recalling the sea creature encounters of Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick. The situations described in the 1851 novel parallel the embodied tensions explored in The Squid and the Whale. In the novel, whales appear at times as monumental, mighty, white or pastel-toned presences that dominate the scene. At other moments, they emerge as old, wounded, and exasperated. This duality is also present in the formal qualities of Joffe’s painting in both the mightiness and vulnerability of her body. Melville’s squid, by contrast, is introduced as the ‘food of the sperm whale’ that ‘lurks at the bottom of that sea’, and first appears to the protagonists as ‘a vast pulpy mass’ with ‘innumerable long arms radiating from its centre, and curling and twisting like a nest of anacondas, as if blindly to clutch at any hapless object within reach’, while capable of appearing and disappearing with startling speed.17 This monumentality of the whale and the elusiveness of the squid were depicted in 1930 by the American modernist illustrator and sailor Rockwell Kent in an early illustrated edition of the novel (Fig. 3 and Fig. 4). Joffe evokes Esme’s squid-like qualities through the blue stripes of her dress, which graze the maternal body with a tentative intimacy. These lines, however, are far from signifying ensnaring tentacles and instead suggest a soft recoil, inviting the viewer to consider the child’s nascent autonomy and process of detachment. Indeed, in a 2018 interview, Joffe discussed her paintings of mother and children as a kind of quiet devastation which is

very much about the heartbreak of the child separating itself from you, that process of detachment. Your desire is still to own and to protect and to care for them, but they want it differently, they don’t want to be smothered. And in some of the paintings I am literally doing that to Esme.18

While Moby-Dick lends mythic scale to the painting’s formal logic, it is the works of J. D. Salinger that anchors her emotional register. The Catcher in the Rye (1951) is one of Joffe’s favourite books and her daughter is named after Salinger’s short story ‘For Esmé—with Love and Squalor’ (1950).19 This same title was used for her 2020 Arnolfini exhibition, which traced the evolving mother-daughter relationship through self-portraits and depictions of Esme with an emphasis on the mother being cared for during an illness. In Salinger’s story, the precocious and emotionally intelligent Esmé offers solace to a traumatised soldier.20 Joffe’s Esme similarly embodies empathy but avoids resolution, complicating the caregiving dynamic. Her presence carries a curious mix of poise and hesitation, as if she registered the emotional weather around her without moving to disrupt it or fully stepping into its space. She offers attention rather than comfort, creating a charged interval where empathy flickers without settling into certainty.

The connection to the museum diorama in both Baumbach’s and Joffe’s work resonates with a moment in The Catcher in the Rye, in which Holden Caulfield, an American icon of adolescent unrest, revisits the American Museum of Natural History. Unlike Walt and Esme, who confront breaks and tension, Holden finds comfort in the stillness of the displays he knew since his childhood. Nonetheless, the permanence of the museum’s scenes stands in contrast to his inner turbulence, revealing a desire to preserve the innocence of childhood and resist the flux of adult life. ‘The best thing, though, in that museum was that everything always stayed right where it was. Nobody’d move’, he reflects as he moves through the exhibition.21 Joffe’s The Squid and the Whale continues the temporal and emotional tensions present in Salinger’s museum scenes but pushes the narrative further towards one of instability and transition.

Expanding upon the intertextual foundations from Salinger and Baumbach, Joffe’s evocation of the whale resonates with older mythic stories. Joffe herself was raised by a secular Jewish father and a Christian mother in a philosophically hybrid household shaped by the rich symbolic universe of her mother.22 Popular stories such as Jonah and the Whale, shared across both Judaism and Christianity, carry an imaginative resonance that exceeds their religious origins. In the biblical narrative, Jonah is swallowed by a whale during a moment of crisis. However, the creature is not simply a site of peril but also a space for reflection and change. This image parallels the maternal body in The Squid and the Whale, which functions simultaneously as a site of refuge and reckoning. Another lesser-known tale in Jewish mysticism recounts the infant Joshua, not Jonah, being swallowed by a sea creature in an episode that serves as a Jewish counterpart to the Oedipal narrative.23 Here the emphasis is not on tragic downfall but on miraculous preservation and future leadership.24 In genesis stories, whales (or great sea creatures) often figure as primordial beings of sacrifice and transformation. The idea that Joffe’s symbolic frame of reference is rooted in Judaic narratives is less significant than the fact that she was immersed in symbolism through her mother’s beliefs and expansive visual imagination.25 In this context, Joffe’s monumental, time-worn maternal figure echoes the womb-like function of the mythic whale, acting as a psychic space against which Esme’s transformation unfolds and the asymmetrical tension of the embodied mother-child dynamic is softly configured. As Joffe explains:

My painting of The Squid and the Whale contains a lot of thoughts about my body and Esme’s—the monumentality of me in relation to her, the way she peeps out from behind the huge body that I am (mothers are enormous to their children both physically and mentally) for all of our lives and also the way the little squid must escape that domination and separate from that huge creature that looms over her.26

By staging the daughter’s psychic and physical detachment as a soft but monumental shift, Joffe portrays what Woodward terms the ‘proliferation’ of generational positions, in which the child simultaneously reflects, defies, and replaces the maternal figure.27 Joffe’s painting thus visualises the emotional labour of separation. What also emerges from the painting, though, is a sense of maternal temporality and a meditation of cyclical generational time.

The Soft Time of Maternal Temporality

If the maternal body in The Squid and the Whale stages the shifting mother-daughter dynamic, it also registers a specifically feminine embodiment of temporality that Joffe renders perceptible through scale, pose, and painterly rhythm. Further literary references help to contextualise this maternal transformation in time. Joffe has cited Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts (2015), where pregnancy and gender transition intertwine to expose the porousness of identity, and Deborah Levy’s The Cost of Living (2018), which articulates the dislocation of self that accompanies motherhood.28 These texts parallel Joffe’s own interest in maternal embodiment as unstable and relational. Although Simone de Beauvoir wrote The Coming of Age in 1970, her reflections remain relevant today and especially to Joffe’s depiction of the changing maternal body. De Beauvoir observes the deep cultural discomfort surrounding ageing women’s (in)visibility and desirability and the social pressures put on women’s aging.29 Joffe, though, refuses this erasure when she makes her body a monumental presence on the canvas. She may depict the body without flattery, but its scale refuses to be diminished. The whale reference highlights this insistence. It recalls the familiar, derogatory associations of female body shame and the cultural pressures placed on women’s bodies, while at the same time evoking the whale’s majestic presence and its mythic role in stories of origin. This tension creates a form of monumentality that is neither idealised nor apologetic; it holds its ground and resists the shrinking effects of a patriarchal gaze. The ambiguity of this large and unsettled form brings into focus Joffe’s interest in moments of temporal rupture, where meaning has not yet settled into place. De Beauvoir’s reflections on ageing reinforce this point by describing time as both the force that shapes the subject and the force that threatens her vitality. This paradox is felt throughout Joffe’s painting, where monumentality and vulnerability sit side by side.

In The Squid and the Whale, this entanglement of time and flesh is visualised through the shifting geometry of the two figures: as the daughter sits upright and alert, the mother leans forward, her figure softened and slumped. The verticality of the child contrasts with the downward pull of the maternal body, marking a moment of inversion in care and dependence. Through this exchange, Joffe sets in motion a quietly devastating shift not only in posture, but in generational power, even as Esme is still sheltered behind her mother. Joffe’s comparison of herself to ‘an old banana in a fruit bowl beside a ripe peach’,30 or a grounded whale lingering beside an alert squid, underscores this soft reversal. When asked about this dynamic, she reflected:

I think the beauty of our children does make us aware of ageing. From the moment I was breastfeeding and saw my own battered-looking hand against her flawless cheek … and now she is a beautiful nineteen-year-old and I compare her to my own ageing self, but that doesn’t allow for the immense joy it gives me to see her in all her beauty, the sheer wonder of that outweighs any sense of loss I might be feeling. I care less and less how I look but I do like to paint all the changes.31

Joffe’s attention to the visibility of ageing puts her maternal figure within a broader tradition of destabilising the reductive stereotypes surrounding older women in western culture. As de Beauvoir observes, representations of ageing people tend to oscillate between two extremes: the serene and wise or the abject and invisible.32 More recently, Woodward highlighted the western binary construction of youth and old age, where youth is culturally idealised as a flexible and valuable category, while old age is fixed, devalued, and continually deferred.33 Joffe unsettles this binary. Her self-depictions are heavy and awkward but rendered with painterly softness and

flexibility that neither flatters nor conceals. In likening herself to a monumental, unwieldy, and slow-moving whale, she registers the weight of motherhood as both a physical and social condition. In The Squid and the Whale, Joffe’s own figure hovers uneasily at the bed’s edge, half-on, half-off, as if on the brink of collapse but nonetheless present. This unbalanced posture echoes Alice Neel’s Self-Portrait, in which Neel confronts her ageing body with arresting candour.34 They both reject the sanitised ideal of the classical nude in favour of a form that is visibly marked by time. In Joffe’s work, the maternal body holds, rather than hides, its history.

The Squid and the Whale, along with its companion pieces The Squid and the Whale II (Fig. 5) and III (Fig. 6), extends Joffe’s meditation on maternal temporality through a progression of visual softening. With each version, the maternal figure bends further from uprightness, her body rendered in increasingly loose, sedimented brush- strokes that make the passage of time physically visible. Though not conceived as a triptych, the sequence suggests both a visual arc of bodily transformation and a reconfiguration of intimacy and dependence. The earliest composition maintains some structural clarity; however, by the final canvas, the maternal form teeters on the edge of abstraction, suggesting not a sudden collapse but a gradual loosening that portrays an unravelling without erasure. Joffe’s bent figure, poised between surrender and persistence, makes time palpable through the very texture of paint. In weaving together the linear trajectory of ageing with the cyclical temporality of maternal experience, Joffe develops a visual idiom in which the ageing body is not diminished but made durational and emphatic. Her work upsets the binary of decline versus transcendence, offering instead a vocabulary of softness to depict an embodied temporality marked by rhythm, density, and the quiet, repetitive labour of care.

A further perspective on generational reversal emerges in the work of Miriam Schaer, whose practice carries the dynamic from Joffe’s painting to its logical conclusion. Schaer’s work often explores the condition of not being a mother and the discrimination faced by childless women, as seen in projects such as Babies (Not) On Board (2013) and the photographic and book series The Presence of Their Absence (2013-15).35 In these works, she appears among hyperrealistic baby dolls, flinging them into the air or standing amid their unsettling gazes. The staging also draws attention to the disjunction between her visibly ageing post-reproductive body and the enduring identification of female identity with motherhood. A second trajectory emerged in the artist’s book (W)hole: A Life in Parts (2017), prompted by Schaer’s mother’s progression through the final stages of dementia.36 The mother needed increasingly more care but responded positively to a life-like baby doll, and photographs show her handling it with unmistakably maternal body movements which persist even as she became more vulnerable and childlike.37

Joffe’s The Squid and the Whale captures the earliest flicker of the same reversal of care and cyclical time. As the daughter sits upright and poised, the mother slumps forward, enacting a quiet but profound shift in generational dependence. This transition, captured at the threshold between the daughter’s youth and the mother’s menopause, is both biological and emotional. Joffe herself describes this temporal gap: ‘As their [children’s] skin grows lovelier, your skin is less lovely … they’re so new and alive at the very moment you get more tired’.38 Her figure, stripped of clear gender markers and with the breast hidden by her arm and shoulder, becomes a vessel for both care and exhaustion. In her analysis of the aging female body in the works of Bourgeois, Rachel Rosenthal, and Nettie Harris, Woodward has identified this stage of life as a key cultural divide in perceptions of female ageing, where fertility defines the symbolic boundary between youth and old age.39 However, rather than depict ageing as a gradual process of disappearance, Joffe presents it as monumentality. Her body does not wither or recede; it accumulates and dominates the canvas, pressing into the frame and displacing the child figure to the background. This logic aligns with what Rosemary Betterton identifies as feminine temporality in the works of contemporary artists depicting motherhood: a cyclical, nonlinear experience of time shaped by the repetitions and recursions of female embodiment.40 For Betterton, temporality in these works involves a process of passage, meaning a crossing between different states of being where time is not only biological or mechanical but also psychic, experienced through patterns of change and stasis.41 Joffe belongs to this cohort, as her sense of time is shaped by the psychic shift that occurs when the daughter begins to contemplate the mother’s fragility with new awareness.

Seeing Mother and the Reversed Gaze

When The Squid and the Whale is read alongside its companion pieces, II and III, an interlocking dynamic of looking emerges. In the first painting, Esme’s gaze is directed toward the viewer in a manner that suggests her eyes are about to lower toward her mother, establishing a doubled gaze that simultaneously engages with the internal logic of the painting and with the external space beyond the canvas. While Joffe’s eyes are fixed on a point beyond the frame in this initial composition, Esme’s direct confrontation with the viewer gestures toward an awareness of the evolving relational dynamic between mother and daughter. In II, Esme’s gaze softens, and Joffe now meets the viewer with a sidelong glance, implying a moment of mutual recognition between the two figures and a tacit acknowledgement of their shifting roles. Esme’s hand also appears here, emerging in the same pink and brown tones as her mother’s, from behind Joffe’s torso. This anticipates the final and more highly abstracted canvas, III, in which Esme’s ambivalent hand gently rests on her mother’s back. Esme now looks down at Joffe, who is rendered in melting brushstrokes that signal dissolution and transformation. In this final image, Joffe’s resigned stare neither engages with the viewer nor appears to focus on anything within the pictorial space, suggesting both a withdrawal and a surrender to a new dynamic. However, by sheer impact of scale, she does not disappear. As Marianne Hirsch observes in her study of psychoanalysis and mother-daughter narrative plots, such moments reveal the possibility of ‘two voices’, in which the daughter’s looking becomes a relational mode that opens a space for maternal subjectivity rather than speaking over it, countering what is more commonly found in traditional narratives.42 Read through Hirsch’s theory, Joffe’s final canvas visualises this dual voicing: Esme’s gaze does not eclipse the mother but participates in affirming her presence to allow fragility and endurance to coexist within the same pictorial frame.

The child here emerges simultaneously as both mirror and maker of the ageing maternal self while offering the viewer commentary on maternal vulnerability. The maternal gaze which is typically understood as directed toward the child is giving way to the child’s gaze upon the mother. This inversion disrupts traditional narratives of motherhood, where the maternal body is conventionally seen as immutable, a fixed anchor for the child’s development. Instead, Joffe presents this body as visibly marked by time, a site upon which both emotional intimacy and inevitable detachment unfold. Esme’s gaze is central to understanding this shift. Through her upright posture and attentive look, she becomes a witness to her mother’s ageing, registering the transitions occurring in their relational roles. The maternal body, previously the source of care, becomes an object of scrutiny. Joffe’s rendering of this gaze, which is marked by a fragile softness that resists categorisation as either clinical or sentimental, captures the ambivalence that Hirsch identifies as central to the mother-daughter relationship: one marked by a simultaneous longing for union, a struggle for separation, and a tension in which intimacy and detachment coexist in unresolved proximity.43 However, as Hirsch argues, feminist psychoanalytic theories primarily frame the mother through the developing child’s perspective, inevitably positioning her as ‘an object, always distanced, always idealized or denigrated, always mystified, always represented through the small child’s point of view’.44 Joffe actively resists this limitation by both including the child’s gaze but foregrounding maternal subjectivity not as a static symbol of nurturing stability but as an evolving entity laden with emotional complexity.

In Joffe’s paintings discussed here, the reversal and cyclical nature of care where the child sees the mother ageing emerges as a moment of soft but emotionally charged transition disrupting linear models of generational succession. The complex acts of looking throughout the whole series—Esme’s at the viewer (Fig. 1 and Fig. 5) and the mother (Fig. 6) and Joffe’s at the viewer (Fig. 5) and nowhere in particular (Fig. 1 and Fig. 6)—intensifies a mood of quiet melancholy, while Joffe’s slumped posture gestures toward a linear narrative of physical decline alongside a psychic cyclical exchange. However, this apparent decline is offset by the cyclical structure embedded in the mother-daughter relationship itself. Julia Kristeva’s notion of feminine temporality, described as spatial, immersive, and governed by cycles of gestation and caregiving, is especially resonant here. For Kristeva, the maternal subject dwells within these repeating rhythms rather than moving linearly through time and instead inhabits a ‘monumental temporality’.45 Joffe’s monumental figures, rendered in soft, expressive brushwork, collapse past and present into a unified presence, resisting simplified narratives of ageing or role dissolution. As Hirsch notes, mother-daughter plots often unfold within repeating temporal loops, a structure made starkly visible in Schaer’s work, where ageing is not only a linear decline into dementia but also a return to earlier forms of dependence and reciprocity.46 Glimpses of this same cyclical dynamic surface in Joffe’s painting, where Esme begins to register her mother’s emerging vulnerability.

This layering of temporalities is vividly exemplified in Self-Portrait with Esme in a Striped Nightie (Fig. 7, 2017), showed in the touring exhibition Acts of Creation: On Art and Motherhood (2024-26), where the relational structure appears less inverted than in The Squid and the Whale and instead serves as a visual prelude to it.47 In this earlier canvas, Joffe’s posture remains upright and less encumbered, while Esme averts her gaze, withdrawn and self-contained. By contrast, in The Squid and the Whale, Esme’s gaze meets the viewer head-on. It is unflinching, quietly assertive, and emotionally opaque. Indeed, the painting enacts a dynamic that Woodward notes in Eva Figes’ novel Waking (1981):

The daughter thus repeats in a certain sense the life of her mother. If from birth on she is always a daughter to her mother, as she grows older she becomes a mother to her daughter. As she ages, she becomes a mother to her mother.48

Positioned behind her mother, Esme occupies a visual vantage point that gives form to the conceptual inversion of the maternal gaze: the child is no longer only the one who is seen but now also the one who sees. Her gaze, steady and direct, intensifies this reversal, marking a shift in visibility and agency between mother and daughter. As Hirsch argues in her theorisation of cyclical womanhood:

Inasmuch as a mother is simultaneously a daughter and a mother, a woman and a mother, in the house and in the world, powerful and powerless, nurturing and nurtured, dependent and depended upon, maternal discourse is necessarily plural.49

Joffe’s visual language aligns with this plurality, portraying motherhood not as a fixed identity but as a mutable state, suspended between roles and emotional intensities. This instability is made materially visible in Joffe’s recurring use of the foetal posture: the maternal figure, limbs curled inward, and body folded into itself, assumes a pose not of rest but of symbolic inversion. In this contracted form, the mother no longer stands as the all-giving presence but as one who returns to a state of need and seems unguarded and exposed. By highlighting this physical vulnerability, Joffe reframes the maternal body as a site of psychic intensity and introspection. The mother is not simply a nurturing vessel, but a subject in flux, caught between care and collapse.

In this sense, Joffe reorients the gaze: the painting does not simply represent the mother-child relationship but actively interrogates it, exposing its fragility and capacity for inversion. The mother’s foetal posture becomes a site of conceptual slippage, where the boundaries between nurturer and nurtured dissolve, and maternal identity is rendered as contingent, oscillating between presence and retreat. Far from presenting a static archetype, Joffe offers a vision of motherhood as fluid and unresolved and defined as much by withdrawal and introspection as by care and protection. It is through this soft, contorted bodily language that she accesses the deeper emotional terrain of maternal subjectivity, one that registers the complexities of dependence, reversal, and relational vulnerability. In The Squid and The Whale, the physical vulnerability of the mother and the composed, unflinching presence of the daughter create an emotional landscape in which roles are no longer anchored by traditional linearity but are continuously redefined through time and the lived texture of the body.

Joffe’s The Squid and the Whale offers a soft but striking reflection on the evolving relationship between mother and daughter. Drawing on emotionally charged moments from literature and film, the painting weaves together personal memory and cultural reference by borrowing its title from Baumbach’s film and evoking the museum scenes in J. D. Salinger’s fiction. These allusions enrich the painting’s own meditation on change, body, and familial distance. At the centre of the composition is the child’s gaze: Esme does not look away. Her stillness contrasts with the folding, slumped body of the mother. This visual exchange suggests a transition and a shift in perspective. Through gesture, posture, and scale, it captures the asymmetrical nature of emotional transition. The mother appears monumental, but the child is the one holding steady. Though soft in both palette and mood, Joffe’s unpolished brushwork eschews sentimentality in favour of emotional ambiguity while inviting reflection. Her depiction of motherhood sits at the intersection of care and ambivalence. As the child begins to separate, the mother leans in. This moment, neither tragic nor complete, is a study in duration. By placing the maternal body in conversation with stories that span from biblical myth to modern cinema, Joffe turns an ordinary domestic moment into a layered scene of transformation and transition. This approach to embodied temporality, particularly as viewed through the eyes of the child, invites further study across Joffe’s wider body of work. It also opens up possibilities for examining how intergenerational time and emotional memory play out across Joffe’s whole oeuvre.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Chantal Joffe for her interviews and insights, to Dorothy Price for her research support, to Isabelle Young for her guidance on aspects of Joffe’s practice, and to Virginia Sirena for providing images and further insights into Joffe’s life and work. Their contributions shaped this piece in essential ways.

Citations

[1] For Joffe’s statements on Freud and Neel, see: David Hermann and Chantal Joffe, ‘Flesh in Paint and Paint is Flesh: A Conversation with Chantal Joffe’, in David Hermann, Lucian Freud: New Perspectives (National Gallery Company Ltd, 2022), 180-185.

[2] Adrienne Rich, Of Woman Born: Motherhood as Experience and Institution (Norton, 1976); Jane Lazzare, The Mother Knot (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1976).

[3] See, for example: Shirley N. Garner, Claire Kahane and Madelon S. Sprengnether, The (M)other Tongue: Essays in

Feminist Psychoanalytic Interpretation (Cornell University Press, 1985); Brenda O. Daly and Maureen T. Reddy, eds., Narrating Mothers: Theorizing Maternal Subjectivities (University of Tennessee Press, 1991); Lisa Baraitser, Maternal Encounters: The Ethics of Interruption (Routledge, 2009); Andrea O’Reilly, Matricentric Feminism: Theory, Activism, Practice (Demeter Press, 2021).

[4] Lucy Lippard, ‘The Pains and Pleasures of Rebirth: European and American Women’s Body Art’, in From the Centre: Feminist Essays on Women’s Art (E. P. Dutton & Co., 1976), 121-138. On motherhood in

art see, for example: Stewart Buettner, ‘Images of Modern Motherhood in the Art of Morisot, Cassatt, Modersohn-Becker, Kollwitz’, Woman’s Art Journal 7, no. 2 (1986): 14-21; Andrea Liss, Feminist Art and the Maternal (University of Minnesota Press, 2009); Myrel Chernick and Jennie Klein, eds., The M Word: Real Mothers in

Contemporary Art (Demeter Press, 2011); Rachel Epp Buller, ed., Reconciling Art and Mothering (Ashgate, 2012); Natalie Loveless, ed., New Maternalisms: Redux (University of Alberta, 2018); Rosemary Betterton, Maternal Bodies in the Visual Arts (Manchester University Press, 2018); Elena Marchevska and Valerie Walkerdine, eds., The Maternal Structures in Art: Inter-generational Discussions on Motherhood and Creative Work (Routledge, 2019).

[5] For recent solo or dual exhibition catalogues, see: Sacha Craddock, Women: Chantal Joffe (Victoria Miro, 2003); Neal Brown and Sacha Craddock, Chantal Joffe (Victoria Miro, 2008); Louise Yelin, Chantal Joffe: Night Self-Portraits (Cheim & Read, 2015); Sarah Howgate, Friendship Portraits: Chantal Joffe & Ishbel Myerscough (Flowers Gallery, 2015); Gemma Blackshaw, Chantal Joffe (Victoria Miro, 2016); Dorothy Price, Gemma Blackshaw, and Olivia Laing, Personal Feeling is the Main Thing (Elephant; Victoria Miro; The Lowry, 2018); Olivia Laing, Chantal Joffe: The Front of My Face (Victoria Miro, 2019); Gary Topp, Gemma Brace, Dorothy Price, and Charlie Porter, Chantal Joffe: For Esme—with Love and Squalor (Arnolfini, 2020). For a group exhibition including Joffe’s works and focusing on motherhood see: Hettie Judah, Acts of Creation: On Art and Motherhood (London: Thames & Hudson, 2024). The Squid and the Whale in particular was briefly discussed in relation to motherhood in: Harriet Baker, ‘Mother Courage’, Apollo, May 2018, 66-71.

[6] Rebecca Morrill, Karen Wright and Louisa Elderton, eds., ‘Chantal Joffe’, in Great Women Artists (Phaidon, 2019), 201.

[7] For these juxtapositions, see: Dorothy Price, ‘Fierce Love’, in Price, Blackshaw, and Laing, Personal Feeling is the Main Thing, 11-15; Dorothy Price, ‘Love Letters’, in Topp, Brace, Price, and Porter, Chantal Joffe: For Esme—with Love and Squalor, 18-26. See also: Dorothy Price and Chantal Joffe, ‘To be a painter is to be alive’, in Dorothy Price, Chantal Joffe, Shulamith Behr, Sarah Lea, and Rhiannon Hope, Making Modernism: Paula Modersohn-Becker, Käthe Kollwitz, Gabriele Münter, Marianne Werefkin (Royal Academy of Arts, 2022).

[8] Kathryn Brown, ‘Pearl Divers’, in Dialogues with Degas: Influence and Antagonism in Contemporary Art (Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2023), 131-165. Joffe, in turn, has served as a reference point for contemporary artists in the depiction of melancholy. See: Mike Newton, ‘Learning from Others’ (PhD Dissertation, School of Art and Design, Bath Spa University, 2013).

[9] Charlotte Mullins, ‘The Figure Unravelled’, in Painting People: Figure Painting Today (Distributed Art Pubs, 2006), 18-54.

[10] Damien Freeman and Derek Matraves, eds., Figuring Out Figurative Art: Contemporary Philosophers in Contemporary Painting (Routledge, 2015), 103.

[11] Price, Blackshaw, and Laing, Personal Feeling is the Main Thing.

[12] Isabelle Young, then Chantal Joffe’s studio manager, confirmed in an email to the author (Orlando Giannini) on 25 March 2024 that the painting is titled after Baumbach’s film and that Joffe saw the diorama at the Natural History Museum while living in New York.

[13] Dorothy Price in conversation with the author (Orlando Giannini) at the Courtauld, London, 7 February 2024.

[14] Chantal Joffe, personal communication with the author (Orlando Giannini) via email on 15 April 2024.

[15] Kathleen Woodward, Aging and Its Discontents: Freud and Other Fictions (Indiana University Press, 1991), 12.

[16] Woodward, Aging and Its Discontents, 12.

[17] Herman Melville, Moby-Dick; or, the Whale (Harper & Brothers; Richard Bentley, 1951), 234, 308-311.

[18] Baker, ‘Mother Courage’, 70.

[19] Isabelle Young confirmed in an email to the author (Orlando Giannini) on 25 March 2024 that one of Joffe’s favourite books is The Catcher in the Rye and that her daughter Esme is named after Salinger’s story ‘For Esmé—with Love and Squalor’.

[20] J. D. Salinger, ‘For Esmé—with Love and Squalor’, in For Esmé—with Love and Squalor and Other Stories (Hamish Hamilton, 1953). First published in the The New Yorker in 1950.

[21] J. D. Salinger, The Catcher in the Rye (Bantom Books, 1964), 121.

[22] ‘My dad was Jewish, my mum Christian—a mixed marriage, and we were brought up without any religion apart from my mum’s fierce morality, which was more philosophical and mystic, a hybrid of Buddhism, Catholicism, Sufism … maybe a religion of books and being good.’ She describes how her father ‘despised religion in all forms and was a scientist’. Chantal Joffe, personal communication with the authors (Orlando Giannini and Ana-Maria Milčić) via email on 3 June 2025.

[23] Howard Schwartz, Tree of Souls: The Mythology of Judasim (Oxford University Press, 2004), 393-394.

[24] Schwartz, Tree of Souls, 393-394.

[25] ‘A beetle suffers all it can when it is trodden on—my mum had a lot of sayings, live as if your actions would be made law.’ Chantal Joffe, personal communication with the authors (Orlando Giannini and Ana-Maria Milčić) via email on 3 June 2025.

[26] Chantal Joffe, personal communication with the author (Orlando Giannini) via email on 15 April 2024.

[27] Woodward, Aging and its Discontents, 97.

[28] Baker, ‘Mother Courage’, 68.

[29] Simone de Beauvoir, The Coming of Age, trans. Patrick O’Brien (G. P. Putman’s Sons, 1972), 297, 321. Originally published in French in 1970.

[30] Alistair Sooke, ‘Chantal Joffe “I don’t find men very interesting to look at”’, The Telegraph, 11 January 2016.

[31] Chantal Joffe, personal communication with the author (Orlando Giannini) via email on 15 April 2024.

[32] De Beauvoir, The Coming of Age, 3-4.

[33] Woodward, Aging and its Discontents, 6.

[34] Joffe spoke about Neel in Hermann and Joffe, ‘Flesh in Paint and Paint is Flesh’, 180-185.

[35] Miriam Schaer, ‘The Presence of their Absence’, Rollins College Book Arts Collection 89 (Miriam Schaer, 2013); Miriam Schaer, The Presence of Their Absence: Society’s Bias Against Women Without Children (Ariadne’s Thread, 2014).

[36] Schaer’s mother died in 2014 while The Presence of Their Absence was underway.

[37] Miriam Schaer, (W)hole: A Life in Parts (Miriam Schaer, 2017). On Schaer, motherhood, infertility, childlessness, and her mother Ida, see: Jennie Klein, ‘The Mother Without Child/The Child Without Mother: Miriam Schaer’s Interrogation of Maternal Ideology, Reproductive Trauma, and Death’, in Inappropriate Bodies, ed. Rachel Epp Buller and Charles Reeve (Demeter Press, 2019).

[38] Ian Youngs, ‘Chantal Joffe: Painting Pregnancy and Parenthood’, BBC News, 7 June 2018.

[39] Kathleen Woodward, ‘Performing Age, Performing Gender’, NWSA Journal 18, no. 1 (2006): 162-189, 168.

[40] Rosemary Betterton, Maternal Bodies in the Visual Arts (Manchester University Press, 2014), 141-144.

[41] Betterton, Maternal Bodies in the Visual Arts, 141-144.

[42] Marianne Hirsch, ‘Speaking with Two Voices: Morrison’s Sula’, in The Mother/Daughter Plot: Narrative, Psychoanalysis, Feminism (Indiana University Press, 1989), 176-186.

[43] Hirsch, The Mother/Daughter Plot, 130-138.

[44] Hirsch, The Mother/Daughter Plot, 168.

[45] Julia Kristeva, ‘Women’s Time’, trans. Alice Jardine and Harry Blake, Signs 7, no. 1 (1981): 16.

[46] Hirsch, The Mother/Daughter Plot, 5-7.

[47] Hettie Judah, Acts of Creation: On Art and Motherhood (Thames & Hudson, 2024). See also Amelia Azura Mielniczek’s review of this work in the present volume.

[48] Woodward, Aging and its Discontents, 96.

[49] Hirsch, The Mother/Daughter Plot, 196.