‘It must be said that our artists were praised by the audience, everyone noted the national character of our works’, wrote Martiros Saryan in his memoir recounting his visit to Venice in June and July 1924.1 Saryan travelled to Italy as part of the Soviet Union’s official delegation for its inaugural participation at the XIV Venice International Art Exhibition (XIV Esposizione Internazionale d’Arte della Città di Venezia), also known as the Venice Biennale.2 One of six Armenian artists included in the Soviet section, he was given a prominent place within the pavilion’s display.3 Although the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic did not receive a distinct entry in the official catalogue, all Armenian painters were grouped together along the main wall of the Soviet pavilion’s small hall, with Saryan’s canvases occupying the central position. Installed in the former Imperial Russian pavilion in the Giardini, the Soviet display marked both a symbolic reclamation of imperial space and an experiment in representing the first socialist state abroad.4 The Armenian grouping, led by Saryan, exemplified the intertwining of national and international ambitions that characterised the early years of Soviet cultural diplomacy.

The year 1924 marked a pivotal juncture for the Soviet state. Following Vladimir Lenin’s death in January and the formal recognition of the USSR by Italy in February, the Venice Biennale acquired both symbolic and pragmatic significance as the first major platform for showcasing Soviet culture on the international stage. At the height of the semi-capitalist New Economic Policy (Novaia ėkonomicheskaia politika, NEP, 1921-1928), when limited market reform encouraged selective engagement with the West, exhibitions became testing grounds for the articulation of Soviet modernity through a careful process of rewriting history and establishing cultural lineage.5 Within the genealogy of early exhibitions abroad, situated between the First Russian Art Exhibition (Erste russische Kunstausstellung) in Berlin (1922) and the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts (Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes) in Paris (1925), the 1924 Venice pavilion occupies an intermediary yet underexamined position. Less ideologically codified than its Berlin and Paris counterparts, Venice nonetheless marked an early moment in which the problem of national representation was embedded within international display frameworks.6 It is this tension between diplomacy, identity, and artistic agency that frames the analysis that follows.

Art historian Ol’ga Pevsner’s 2022 study remains the most comprehensive account of the 1924 pavilion and provides a crucial starting point for this discussion. She argues that the substantial Armenian presence was not conceived as a deliberate act of national representation but served instead to craft a stylised image of Soviet multiculturalism, filtered through an Orientalising lens. In this reading, non-Russian artists such as Saryan and Russian artists whose subjects included Central Asia or the Caucasus were mobilised as the ‘shock troop’ within the highly competitive international context of the Biennale.7 While Pevsner interprets this as evidence of a centralised curatorial logic, my analysis shifts attention to the multiplicity of receptions that the pavilion invited across Soviet, Italian, and Armenian émigré publics, and to the hybrid meaning generated in their encounter. Rather than a unified projection of Soviet identity, the pavilion emerges as a mediating site where local, diasporic, and international interpretations coexisted.

This mediating dimension of the Biennale becomes visible in a photograph preserved in the M. Saryan House-Museum in Yerevan (Fig. 1), which shows the artist in Venice with the Armenian poet Avetik Isahakyan and his family. Their encounter, shaped by a longstanding acquaintance dating back to the early 1900s and by the dislocation of exile, war, and revolution reveals the human networks that underpinned the circulation of art and ideas in this period, complicating later readings of the pavilion as purely state-managed diplomatic instrument. Shortly after, Isahakyan published a review in the Paris-based Armenian-language journal Hayrenik (Homeland), offering a rare diasporic response to the exhibition.8 Such happenstances, unfolding beyond the institutional stage of the Biennale, invest the works with affective meanings that existed alongside, rather than against, the pavilion’s official message. Saryan’s position, therefore, cannot be reduced to either ideological instrument or national dissident alone, but embodied the layered identity of an artist who was at once republican, Soviet, and diasporically resonant. His contribution reveals how state interest, national agency, artistic ambition, and émigré interpretation could coexist—a polyphony rooted in the political and cultural conditions of the early 1920s.

My analysis brings these strands together by pairing institutional history with reception history, attentive to the multiple registers in which Soviet and Armenian identities were articulated. The pavilion formed part of an early Soviet exhibition apparatus that was simultaneously pedagogical and diplomatic: displays were tasked with projecting vitality abroad while cultivating domestic standards of taste and education. What Pevsner has termed a ‘stylised multiculturalism’ calibrated to European sensibilities, was also consistent with the emerging nationalities discourse of the early 1920s. Under the policy of korenizatsiia (indigenisation), ethnic particularism was not merely permitted but actively encouraged, so long as it reinforced the ideological coherence of the Union.9 As later captured by Yuri Slezkine’s ‘communal apartment’ metaphor, cultural differences were made visible, even celebrated, while political authority remained centralised: the 1924 exhibition offers an early materialisation of this dynamic.10

Within this framework, the Armenian wall functioned as a staged pedagogy of plurality that nonetheless left space for artistic agency. Saryan’s relocation to Yerevan in 1921, at the invitation of the Soviet-Armenian authorities, enabled him to shape museums, schools, and symbols of state identity, situating him not simply as Moscow’s delegate but as an active participant in Armenia’s cultural consolidation. The presence of other established Armenian painters—Sedrak Arakelyan, Yegishe Tadevosyan, and Panos Terlemezian—alongside drawings by Vardges Sureniants and Taragros Ter-Vardanyan, reinforced a sense of cultural continuity rooted in late-imperial networks yet reframed through socialist renewal.11 These dynamics form the institutional and political context through which Saryan’s role in Venice 1924 can be understood.

At the same time, diaspora reception adds a further dimension to this curated plurality. For émigré audiences, Saryan’s paintings could evoke homeland in several registers: as the political present of Soviet Armenia, as a civilisational continuum, and as the intimate geographies of personal memory. These readings did not stand in opposition to the pavilion’s official message but coexisted with it. To conceptualise this multiplicity, I draw heuristically on historian Maike Lehmann’s account of late-Soviet Armenia as a hybrid articulation of national past and socialist future, and on cultural anthropologist Susan Pattie’s notion of diaspora homelands as multiple and continually in formation.12 Together, these frameworks illuminate how Saryan’s imagery generated meanings across different publics without collapsing into either ideological instrumentality or national essentialism.

Today, Saryan’s oeuvre is often framed as the quintessential expression of Armenian identity, with the House-Museum claiming that ‘the name Armenia and Saryan are inseparable’.13 In 1924, however, this national essence was refracted through the optics of Soviet exhibition culture. The Biennale functioned simultaneously as an arena of soft power and as a site of representational multiplicity, where cultural unity and plural interpretation were not incompatible but mutually sustaining. Rather than reconstructing the pavilion in its entirety, this study uses Saryan’s participation to examine how national and socialist vocabularies were negotiated within early Soviet cultural diplomacy.14 Drawing on scholarship that treats exhibitions as mediating structures, the article reads display practices as a space where the boundaries between representation, propaganda, and exchange were actively negotiated.15

The article advances two related claims. First, the pavilion exemplifies an early Soviet strategy of curated heterogeneity in mobilising national culture—here Armenian painting—as both a diplomatic asset and an emblem of socialist modernity. Second, Saryan’s case demonstrates how a single display could sustain multiple readings without collapsing into incoherence. Focusing on Saryan’s display, specifically his landscapes painted after 1921, reveals how national visibility, diasporic resonance, and state strategy could coexist in productive hybridity, complicating binary readings of centre and periphery, resistance and compliance. Far from incidental, the Armenian presence at Venice emerges as a key site through which to understand how early Soviet cultural diplomacy navigated multiplicity, and how this moment helps us nuance the role of national artists within the transnational encounters of the early 1920s.

From Pedagogy to Display

The organisation of the Soviet pavilion in Venice in 1924 was inseparable from the intellectual discourse of the early 1920s, when art institutions were envisaged as instruments of social pedagogy and as laboratories for shaping perception. Under Anatolii Lunacharskii, People’s Commissar for Enlightenment (Narodnyi Komissariat Prosveshcheniia, Narkompros), culture was defined as a pedagogical tool for shaping mass consciousness and cultivating the new Soviet subjects.16 In 1921, the theses of the Visual Arts Section of the Academic Centre of Narkompros (Khudozhestvennyi sektor NKP, IZO Narkompros), co-authored by Lunacharskii and Yuvenal Slavinskii and published in the first volume of Iskusstvo (Art) journal, articulated the official Party line on art as ‘a powerful means of infecting those around us with ideas, feelings, and moods’, insisting that propaganda gained greater force when ‘clothed in the attractive and mighty forms of art’.17 At the same time, the theses stressed continuity: proletarian culture was to draw on the artistic inheritance of the past, critically stripped of its ‘anti-revolutionary and philistine aspects’.18 This deliberately broad conception of culture allowed Narkompros to mediate between the competing agendas of artistic groups, union organisations, and academic institutions.

Within this framework, responsibility for the pavilion was entrusted to the Russian Academy of Artistic Sciences (Rossiiskaia Akademia khudozhestvennykh nauk, RAKhN), established in Moscow in 1921 at the initiative of Narkompros to coordinate academic research in the arts and humanities. RAKhN’s remit was explicitly experimental: to direct research in the psychology, sociology, and philosophy of art, and to translate that work into pedagogical and exhibitionary practice.19 Its membership encompassed diverse tendencies, from preservationists to avant-garde figures such as Vasilii Kandinskii, whose plan for the Academy’s Psychophysiological Department, presented before his departure for Germany in 1921, called for systematic studies of perception of colour and form in children, psychiatric patients, and ‘primitive peoples’ as means of understanding how art shaped audiences.20 This intellectual pluralism, and its focus on the social function of artistic form, informed the logic of early Soviet exhibitions: they were conceived not as homogenous assertions of style but as contexts in which heterogeneous pictorial languages could be deployed for pedagogical and diplomatic effect.

The mechanics of the 1924 pavilion reflected this ethos. Under the direction of Petr Kogan, RAKhN’s director and chief commissioner, the critic Abram Efros, devised the initial layout, assigning individual walls to the ‘major’ artists to foreground their contribution. The display encompassed works in a wide range of media, from painting and works on paper to sculpture, decorative arts, theatre designs, posters, and even a section dedicated to children’s drawings. Yet within this profusion, painting remained dominant, including realist military-themed canvases by members of the Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia (Assotsiatsiya khudozhnikov Revolyutsionnoi Rossii, AKhRR), abstract and non-objective compositions by artists such as Varvara Stepanova and Aleksandr Rodchenko, as well as landscapes, portraits, still lifes, and genre scenes. According to the Biennale’s catalogue, fifty-four artists exhibited 176 paintings, with nearly four hundred objects in total, making the Soviet contribution among the densest in Venice that year.21

This internal arrangement further reflected the experimental outlook of RAKhN’s members, particularly Soviet art historian and pedagogue Anatolii Bakushinkii. Having succeeded Kandinsky as head of the Psychophysiological Department in 1922, Bakushinkii sought to unite perceptual psychology with the formal study of artistic methods. His department’s programme focused on analysing the materials, form, construction, and composition of artworks within an institutional and empirically oriented framework.22 Reflecting the growing importance of formal analysis within Soviet art-historical discourse, this approach rested on the conviction that form was not merely an aesthetic surface but a cognitive mechanism through which social meanings could be produced and apprehended. As art historian Maria Silina has shown, this ethos of ‘institutionalised multidisciplinarity’ integrated theory, experiment, and exhibition practice as interdependent components of a single methodological field.23 Although Bakushinskii was not involved in the Biennale’s organisation, and the pavilion was not conceived as a literal ‘laboratory’, its curatorial logic was consonant with RAKhN’s concerns: a practical exploration of how heterogeneous pictorial languages could elicit sensory and emotional responses. The display’s apparent stylistic range—from realism to non-objectivity—thus functioned less as a sign of incoherence than as a deliberately modulated trajectory of affect, mirroring the contemporary understanding of form as both pedagogical and ideological instrument.

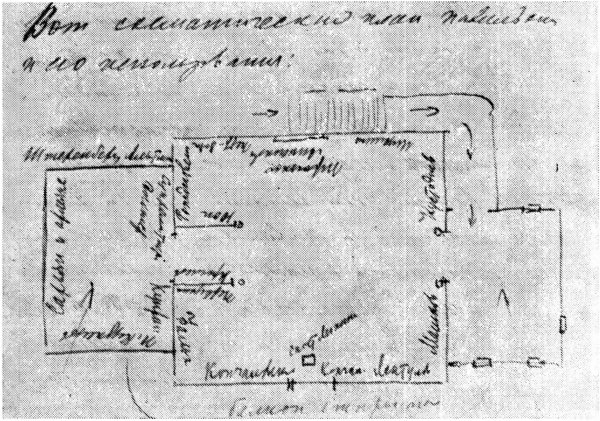

With Efros unable to travel to Venice for the opening, curatorial responsibility fell to Boris Ternovets, a member of RAKhN and director of the State Museum of New Western Art in Moscow (Gosudarstvennyi Muzei Novogo Zapadnogo Iskusstva, GMNZI).24 In a letter dated 29 June 1924—ten days after the Soviet section opened to the Venetian public—Ternovets reported to colleagues in Moscow that the pavilion was provoking ‘critical interest and thoughtful engagement’ from international audiences, despite its belated inauguration two months after the Biennale’s official opening.25>/sup> Enclosed with the letter was a sketch of the floor plan (Fig. 2), in which he labelled the main wall of the final room ‘Saryan and Armenians’. Although the wall also included still lifes by Elena Bebytova and biomorphic canvases by Boris Ender, the annotation underscored the symbolic weight attached to the Armenian contingent and to Saryan in particular.

Although no photographs survive of the small hall in its entirety, a wide-angle view taken from the central room partially captures Saryan’s canvases framed through the archway (Fig. 3). Cross-referenced with Ternovets’ plan, in which arrows indicate the intended visitor route, the photograph confirms that his paintings were hung in the central sightline, drawing the viewer’s eye from the foyer and producing the exhibition’s climactic vista. According to Ternovets’ sketch and accompanying notes, visitors entered via a staircase lined with decorative arts, moved through a foyer displaying works on paper, and then entered two principal rooms allotted to painting and sculpture. The resulting spatial sequence materialised, whether intentionally or not, the perceptual pedagogy circulating in RAKhN circles: a progression designed to lead viewers from instructive realism toward increasingly stylised chromatic intensity and an affective ‘lift’.

Writing from Venice, Ternovets described the Armenian grouping as producing ‘a bright, decorative impression that immediately lifts the mood’, a quality he considered essential to the pavilion’s success with Italian critics.26 Later in the same correspondence, he noted that reviewers emphasised the ‘seriousness and freshness’ of the Soviet section, interpreting it as an optimistic vision of cultural renewal.27 His remarks indicate that decorativeness was not incidental but integral to a consciously staged affective programme, in which aesthetic form, ideological messaging, and emotional response were coordinated with notable clarity.

Curating Ambiguity

The affective register of Ternovets’ description of the Armenian grouping found a ready echo in the pavilion’s contemporary reception. Yet the significance of that effect has often been overlooked or diminished in both Anglophone and Russian scholarship. In her reconstruction of the pavilion’s administrative organisation and contents, Pevsner frames the substantial Armenian presence not as a gesture toward national representation but as a stylised manoeuvre, a way of producing an attractive, decorative image of Soviet identity for western audiences.28 Saryan’s landscapes, along with Central Asian steppes in the works of Pavel Kuznetsov, are interpreted in her account as interchangeable signs of Oriental periphery, visually appealing works that softened the ideological contrast between the artistic left and realist factions.29

While Pevsner’s reading highlights a real curatorial pragmatism, it risks flattening the ideological and institutional logic that shaped the pavilion. Even if no explicit directive on nationality accompanied the selection, the sensibilities cultivated within RAKhN make it difficult to regard this affective arrangement as merely incidental. Rather, it can be seen as an exercise in guiding viewer’s emotional and cognitive responses—an applied extension of the pedagogical principles discussed above. The pavilion’s physical organisation was itself a didactic structure, using brightness, contrast, and formal progression to signal cultural renewal. The small hall housing most Armenian works, positioned at the end of the visitor’s route, thus functioned both literally and conceptually as the display’s culmination.

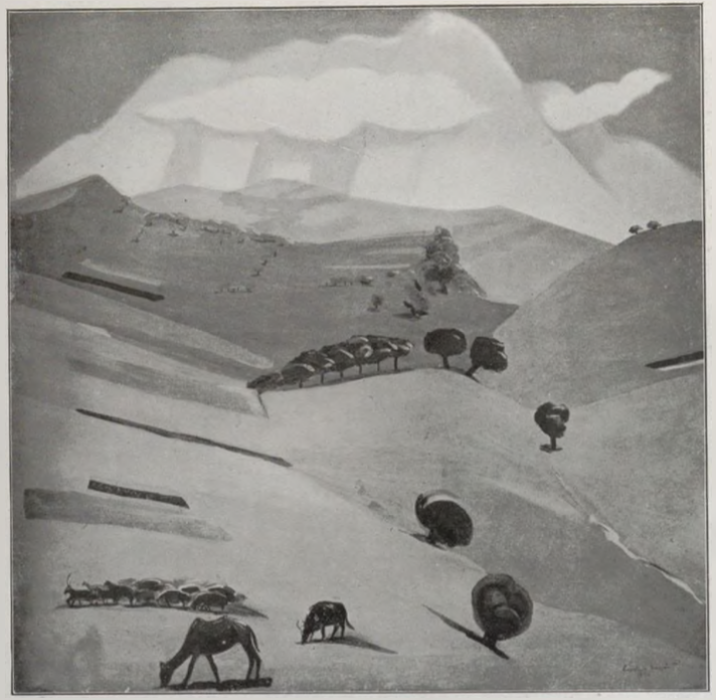

Within this room, painting remained the dominant medium. Moving clockwise from the entrance, the wall to the left was occupied by Alexander Kuprin, whose still lifes and landscapes of church-dotted fields projected a pastoral serenity. The adjacent wall belonged to Kuznetsov, whose pre-revolutionary, dreamlike Symbolist canvases of Central Asia and the Trans-Volga steppe occupied the lower register and can be identified in surviving photographs of the pavilion (Fig. 4). Across the room, to the right of the doorway, hung the Constructivist and Suprematist works of Rodchenko, Liubov Popova, and Kazimir Malevich. The wall facing the entrance was almost entirely devoted to the Armenian contingent. Here Saryan’s five recent landscapes, painted between 1923 and 1924, formed the chromatic and spatial centre, flanked by his portraits and earlier still lifes, while the smaller, more subdued works of Sedrak Arakelyan, Yegishe Tadevosyan, and Panos Terlemezian were arranged along the outer edges.30 This arrangement, with its calibrated symmetry, tonal gradation, and variation of scale, created a sense of visual coherence without prescribing a single meaning. The same sequence signalled cultural renewal to Soviet organisers while appearing as a vivid regional grouping to western viewers.

At the centre of this wall hung Midday Silence (Fig. 5), a large, square canvas positioned as the conceptual keystone of the display and visible through the archway in one of the surviving interior photographs. Rendered in oil, the composition presents a sun-bathed hillside in bands of ochre rising toward a lilac mountain under a translucent blue sky. A small herd grazes in the foreground, their rounded silhouettes echoing the gentle bends of the terrain. The landscape is at once angular and fluid: flat planes of colour replace detail, and depth yields to a pattern of diagonals that pull the eye upward. The result is a scene of stylised pastoral calm, instantly legible to western viewers familiar with the chromatic lucidity of Post-Impressionism. Yet for all its formal ambiguity—the vague title, the absence of human activity—the composition remains anchored in a specifically Caucasian topography by the four-peaked Mount Aragats, long regarded alongside Mount Ararat as sacred in Armenian cultural memory.

It was this combination of recognisable modernist aesthetics and ‘Eastern’ temperament that struck contemporary critics. Among the earliest and most enthusiastic was the Italian reporter Giuseppe Sprovieri, who interviewed Saryan during the press opening and published his account in the newspaper Il Mondo that August. Saryan’s paintings, he wrote,

are a vivid expression of such a strong and original temperament that they […] deserve great attention from the point of view of the search for modern art. There is something in Saryan that recalls western artists—for example [Henri] Matisse. These are the characteristic features of Orientalism. However, Saryan differs from the latter by his exceptional, more direct and clear strength, in other words, by lesser deliberation.31

Sprovieri’s language of temperament, colour, and Oriental character closely echoes the rhetoric employed by the pavilion’s organisers. While this may in part reflect the pragmatics of journalistic practice where critics frequently drew upon official press releases, it also signals the success of a curatorial strategy designed to produce a legible and manageable foreign response. As art historian Boris Chukhovich has argued, early Soviet cultural pluralism operated through what he calls the ‘exclusivity of the inclusive’: a logic in which Orientalist assumptions did not simply repress difference but stabilised it, making cultural variety readable within a Soviet framework.32 Saryan’s reception in Venice exemplifies this dynamic. The very rhetoric that marked him as ‘Oriental’ to western viewers simultaneously allowed Soviet organisers to present diversity as evidence of cohesive, governable multinational culture.

This logic is articulated most clearly in Ternovets’ introduction to the Soviet section of the Biennale’s catalogue, later translated for the French art press.33 There he characterised Moscow as a city whose ‘soul of the East’ found its fullest expression in painting, describing it as a ‘semi-Asiatic’ centre whose artists were uniquely attuned to rhythm, colour, and emotion. Within this vision, Saryan and Kuznetsov served as emblematic figures. Kuznetsov, he argued, had distilled ‘the steppes of oriental life,’ into modern pictorial form, while Saryan, with his vivid harmonies of yellow and violet, and his flat decorative structure, expressed the same Orient ‘with an even sharper and more spontaneous accent’.34 For Ternovets, the productive interplay of modernist formal clarity and ‘Eastern’ expressive charge was not incidental but central to the pavilion’s conception.

Yet this formulation is revealingly double-edged. By translating the question of nationality into a vocabulary of temperament, colour, and spontaneity, Ternovets elided direct references to Saryan’s Armenian identity. This treatment was not dissimilar to that of Kuznetsov, whose painting exhibited in Moscow in 1923 as Kyrgyz Woman with Camels appeared in Venice under the more generic title Girl with Camel.35 Such ambiguity enabled the pavilion to sustain multiple readings: to western critics, the ‘Oriental spirit’ suggested freshness and exoticised authenticity; to Soviet observers it demonstrated the cultural richness of the Union’s republics and the integrative potential of socialist modernity. At the same time, Ternovets’ language affirmed that this vitality stemmed from the ability of Soviet art to absorb and transform the ‘East’ into a shared aesthetic resource. By recasting Orientalism as an internal principle of synthesis rather than an external gaze, the catalogue text made difference legible precisely by aestheticising it.

Such framing also resonates with Saryan’s own artistic trajectory. Born in 1880 into an Armenian farming family in Nakhichevan-on-Don (today part of Rostov-on-Don), near the southern border of the Russian Empire, he belonged to a new generation of Armenian artists who entered the imperial art academies in Moscow and St Petersburg at the turn of the century. Between 1897 and 1904, he trained at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture under Valentin Serov and Konstantin Korovin, engaging with the syncretic currents of late Symbolism alongside fellow student Kuznetsov. Like many of his peers, Saryan sought in colour and form a language of spiritual transformation rather than of naturalistic imitation.36

The years between 1910 and 1913 marked a decisive expansion of this search. Travelling through the Ottoman Empire, Egypt, and Persia, he encountered the chromatic intensity and geometric clarity of Islamic, North African, and Asian visual cultures.37 Art historian John E. Bowlt has described this ‘post-Blue [Symbolist]’ period as a ‘return to life’, a movement away from Symbolist introspection toward what contemporaries perceived as a more immediate, ‘primitive’ authenticity of the East, expressed in the intensified use of warm red and yellow tones.38 These journeys broadened his cosmopolitan vision but also reinforced the self-identification with an imagined eastern world that would soon define his critical reception. In 1913, in the first substantial review of his work, the poet Maksimilian Voloshin wrote in the literary journal Apollon that Saryan possessed ‘an instinctive Eastern soul’, able to fuse the analytic colour of modern European painting with the synthetic forms of the East.39 Saryan embraced this reading, writing to Voloshin the following year that the essay was ‘magnificent’ and ‘founded on truth’, and that he had reread it several times.40 His active appropriation of this ascribed eastern identity illustrates the dynamic identified by Chukhovich: the capacity of the artists to inhabit, adapt, and strategically repurpose codified categories of national difference.

However, Saryan’s sustained engagement with Armenia and the Caucasus long pre-dated these international journeys. His first expeditions through Eastern Armenia in 1901 and 1903—then part of the Russian Empire—took him to archaeological sites in Lori, Shirak, and Echmiadzin, while later travels in 1912 extended into the Ottoman-controlled provinces of Artvin and Ardanuch.41 By this time, Armenia had become for him not merely a repertoire of motifs but a conceptual and emotional landscape. His permanent relocation to Yerevan in 1921, therefore, did not inaugurate his engagement with national culture; rather, it consolidated a long-standing dialogue between place and perception. This extended immersion in Armenia’s terrain and material culture informed his conviction that national character could be communicated not only through narrative subjects or iconographic markers but through the sensory vocabulary of colour, light, and rhythm.

Far from arriving in Venice as an untested or provincial representative, Saryan entered the 1924 pavilion with an established international profile. He had exhibited in Europe since the 1910s, most recently at the 1922 First Russian Art Exhibition in Berlin, exhibiting an earlier work titled Armenian Woman with a Saz (1915, Fig. 6). Executed in tempera, the painting depicts a seated woman beside a long-necked lute used across Armenia, Azerbaijan, Iran, and Turkey. The instrument’s rounded, oversized body dominates the composition, its curves echoed in the patterned textiles and fruit that surround the female figure. Rendered in flat planes of magenta, orange, yellow, and turquoise, and rich with vegetal decorative scrolls, the work fuses the ornamental exuberance of French modernism—familiar to Saryan from Sergei Shchukin’s collection in Moscow—with the spatial compression of Armenian manuscript illumination.42 This synthesis of formal reduction, disjunction of scale and colour, and regional visual traditions exemplified the pictorial language through which Saryan became legible to European audiences in the years preceding Venice.

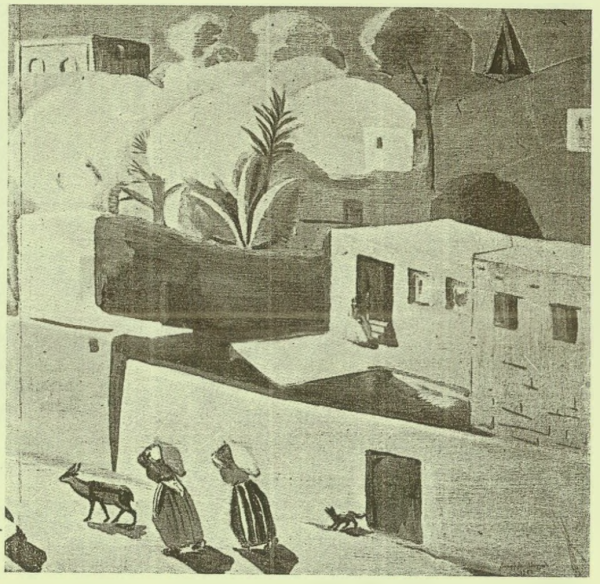

The only work by Saryan sold in Italy in the summer of 1924, Yerevan (1924, Fig. 7), offers a fitting distillation of the pavilion’s aims. The painting presents a high, slightly tilted bird’s-eye view over the city’s historic quarters, where clusters of flat-roofed houses and narrow streets populated by figures of women carrying baskets, alongside goats and dogs whose silhouettes punctuate the warm ochre ground. Though grounded in topography of the newly Sovietised capital, the composition adapts the visual idiom Saryan had developed during his pre-war travels through Cairo, Constantinople, and Tehran with its elevated viewpoint, compressed space, and rhythmic patterning echoing the genre scenes, markets, and street-life compositions of his 1910s canvases. In Yerevan, this idiom is re-situated within a Soviet-Armenian setting, transforming a repertoire once associated with a broader ‘Eastern’ geography into a localised, civic image of republican life. The Italian collector Giovanni Dalla Villa—who also acquired Kuznetsov’s Girl with Camel—was among the few buyers in an otherwise financially unsuccessful Soviet showing.43 That these two works attracted interest is unsurprising: both offered precisely the qualities the pavilion sought to foreground, such as brightness, decorativeness, legibility, and the visible synthesis of regional specificity with modern stylistic clarity.

While this dual reception may be read through what Chukhovich identifies as the Soviet system’s tendency to fix artistic identity along ethnographic and geographic lines, designating certain artists as ‘authentic’ national representatives, it also reveals how such framing could become unexpectedly generative.44 Foreign critics continued to interpret Saryan through familiar Orientalising categories, yet his position within the exhibition and the broader field of Soviet cultural politics was neither peripheral nor oppositional. Instead, operating within the opportunities created by the NEP and the nationalities policy, he exemplified how artists from the republics could inhabit, redirect, and shape the terms of state-directed diversity into vehicles of artistic and cultural agency. In this sense, the 1924 exhibition in Venice demonstrates that ambiguity itself functioned as the operative language of early Soviet diplomacy, and that multiplicity could serve, rather than threaten, the international project of Soviet modernity.

Agency and Belonging

The dynamics that converged in Venice—the rhetoric of openness, the visibility of national cultures, and the performance of unity through difference—reflected the broader cultural politics of the early Soviet nation-building. Codified with the formation of the Union in December 1922, this project combined the administrative creation of republics with the cultural construction of nations. As historian Terry Martin has shown, the Bolshevik nationality policy systematised the formation of national territories, elites, and languages while actively promoting national cultures through museums, publishing houses, and academic institutions.45 The result was a characteristically dual structure of empowerment and control, where cultural autonomy was granted as the very means of integration.

Within this framework, Armenia occupied a distinct position. Incorporated into the Transcaucasian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic (TSFSR) alongside Georgia and Azerbaijan in 1922, following the brief independence of the First Republic of Armenia, it was regarded within Soviet discourse as culturally developed, possessing a consolidated historical consciousness and strong artistic heritage.46 The policy of korenizatsiia, formalised at the Twelfth Party Congress in April of 1923 and pursued within the pragmatic climate of the NEP, promoted the cultivation of local languages and political cadres while integrating the territories into a Union-wide programme of socialist modernisation.47 Within the hierarchy that structured these policies, Armenians and Georgians, alongside Russians, Ukrainians, Jews, and Germans, were classed among the ‘Western’ nationalities, expected to model cultural and economic development for the ‘Eastern’ peoples.48

For artists like Saryan, this political climate created an exceptional, if temporary, field of opportunity in which the depiction of hayrenik (‘homeland’) could operate simultaneously as personal expression, national allegory, and vehicle of Soviet diplomacy. The reconstruction of Armenian cultural and administrative life under Soviet auspices in the 1920s did not emerge in isolation; it extended the cosmopolitan networks of the late-imperial Caucasus, above all Tiflis. A multilingual, multi-confessional city, Tiflis had become a laboratory of regional modernism by the early twentieth century. As literary historian Harsha Ram has shown, its cultural milieu developed not through imitation of metropolitan centres but through the synthesis of its own local entanglements. In the words of the Georgian poet T’itsian T’abidze, it was ‘a child of the city’.49 Armenian, Georgian, Russian, and Persian intellectuals circulated through the same journals and salons, generating hybrid visual and literary idioms that blurred any stable distinction between centre and periphery.

Saryan’s career took shape within this environment. Before the Revolution, he lived between Rostov-on-Don and Tiflis, exhibiting with the Society of Armenian Artists (which he co-founded in 1916) and contributing to Armenian-language journals and nascent museum initiatives. For many Armenian intellectuals, including Saryan, the catastrophe of the 1915 Armenian genocide at the hands of the Ottoman state intensified cultural work as both personal and collective imperative. Their efforts sought to articulate a modern Armenian culture that was diasporic yet locally grounded, a continuity that would later acquire institutional form under Bolshevik rule. The modernism that developed in early Soviet Armenia was therefore not a rupture but an adaptation of these pre-revolutionary circuits to a new political order that aimed to make national cultures visible within the socialist universal.

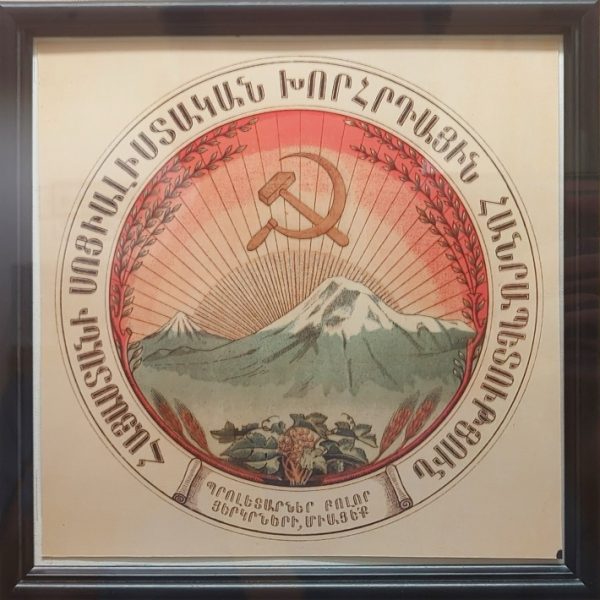

At the invitation of Alexander Myasnikyan, Chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars of Armenia, Saryan moved with his family to Yerevan in 1921, settling there permanently until his death in 1972. Having already participated in the artistic life of Rostov and of the short-lived First Republic, he now collaborated with Ashot Hovhannisian, the People’s Commissar for Enlightenment, to establish the institutional foundations of Soviet Armenia—its museums, art school, and artists’ union.50 Although he painted little during these years, Saryan undertook several state commissions, most notably the emblem of the Armenian SSR (1922, Fig. 8). The early impression, preserved at the artist’s House-Museum, reveals fine gradations of red and amber radiating from behind the twin peaks of Mount Ararat, whose fine black contours are rendered in soft green and grey tones. Delicately rendered sheaves of wheat and grapevines frame the round composition, while the hammer and sickle in the centre complete the image as a unifying device. The emblem translated the rhetoric of Soviet federalism into visual form: a balanced synthesis in which national specificity and socialist universality coexist within a single symbolic field.

The same compositional logic animated Saryan’s 1923 watercolour sketch for the curtain of the newly established Gabriel Sundukyan State Academic Theatre. Replacing the emblem’s static symmetry with a dynamic panorama, the design unfolds as soaring landscape of labour and festivity. Terraced fields, river, dancers, and ploughmen rise through diagonal planes of colour into a visual rhythm that fuses architecture, terrain and human movement into a single motion. Conceived as both a functional stage curtain and a performative declaration of cultural rebirth, the sketch prefigured the logic of the canvases Saryan would present in Venice the following year, where landscape would become an instrument of civic imagination and collective emotion.

The painting Armenia (1923), today housed at the National Gallery of Armenia in Yerevan, gives concrete form to this process of visual and symbolic reconstruction. One of two vertically oriented works in Saryan’s Venice display, it translates the compositional scaffolding of the preparatory sketch for the theatre curtain into more saturated, architectonic medium of oil. Its composition unfolds as a rhythmic ascent: dancers gathered on a rooftop in the foreground, a river threading through fields and terraces, cliffs rising in angular planes, their snowy peaks receding into luminous pastels. Whereas the curtain offered a dynamic panorama for a civic stage, Armenia monumentalised the same visual syntax of stacked diagonals of ochre, pink and blue, and the fusion of architecture, labour and landscape into a unified pictorial field. The result is both a geographic and symbolic image of homeland articulated through the interdependence of environment, ritual, and collective presence.

The painting’s iconography reinforces this synthesis. A medieval stone church perched on the cliff’s edge asserts Christian continuity; the faint, classical contours of the colonnaded Garni Temple in the centre link Armenia’s pre-Christian past.51 Women dancing on the roof of the baniani, stone dwellings typical of vernacular architecture in the Caucasus, echo the circular cadence of the horovel, the traditional Armenian ploughman’s song whose call reverberates through the mountains, binding human effort to natural rhythm.52 This interplay of sacred architecture, agrarian labour, and organic movement are not presented as an ethnographic inventory. Instead, Saryan constructs a total landscape of belonging, one in which the visual language of modernism mediates layered histories.

As historian Ronald Grigor Suny has observed, Armenians entered the twentieth century with a strong sense of cultural continuity but without a continuous territorial state.53 The collapse of the Russian and Ottoman empires, the brief independence of 1918-1920, and the subsequent incorporation into the Soviet Union imbued representations of hayrenik with acute affective and political charge. Seen against this backdrop, Saryan’s emblem, theatre curtain, and landscapes—including Armenia—operate as acts of reconstruction: images that stabilise belonging in symbolic form even as the geopolitical landscape remains unsettled. In Venice, this visual consolidation of homeland became entangled with the pavilion’s diplomatic aims, enabling Saryan’s work to serve simultaneously as national articulation and as a legible component of Soviet multinationalism.

Saryan’s presentation at Venice extended this vision into a wider transnational circuit of meaning. For émigré publics, the idea of Armenia remained both imagined and deferred, and Saryan’s landscapes offered a rare visual condensation of that distance. The most vivid response came from the poet Avetik Isahakyan, then living between France and Switzerland, having been exiled from the Russian Empire in 1911.54 Writing for the Armenian-language journal Hayerenik in August 1924, Isahakyan praised Armenia as ‘a synthesis of our homeland’, evoking its snow-crowned Ararat, stony Aragats, medieval churches, green valleys, and the rooftop dancer of village women. He went on to reflect on the apparent paradox of how, ‘in the middle of the boundless ocean of Russian expanses’, figures like Saryan could emerge, artists ‘whose minds and hearts are Armenia and the Armenian people who understand it’.55 Elsewhere in the review, Isahakyan framed Saryan’s achievement as a foundational moment in modern Armenian culture, arguing that his work both revitalised inherited visual traditions and provided a basis for their future development. Rather than a gesture of cultural resistance, Isahakyan’s appeal to a deep civilisational memory echoed the modernising rhetoric of rebirth that structured early Soviet cultural discourse. His subsequent relocation to Soviet Armenia in 1936, at the government’s invitation, demonstrates how such attachments could evolve from diasporic sympathy into institutional participation.

Such responses illustrate what historian Maike Lehmann describes as a hybrid repertoire of Armenian self-understanding, in which national past and socialist future were articulated together rather than held in opposition.56 Although Lehmann’s study focuses on the late Soviet period, her framework is productive for the NEP era, when the language of korenizatsiia similarly bound national affirmation to socialist modernity. In Venice, administrative sanction by the Soviet state and emotional investment by the diaspora worked in tandem: the state codified national culture, while émigré publics extended its affective reach. At the same time, as anthropologist Susan Pattie argues, diaspora identity is ‘continually in the process of construction’, sustained through multiple parallel homelands—the present republic, an ancient civilisational past, and the intimate landscapes of familial memory.57 Pattie also notes that Soviet Armenia was encouraged to function as a cultural ‘repository’ for the diaspora, a site deliberately cultivated by the USSR to attract goodwill and, where possible, return migration. This context sharpens the stakes of Venice: the pavilion did not merely mirror diasporic attachments but formed part of a broader political strategy that made such attachments legible and usable to the Soviet state. Saryan’s imagery, with its fusion of near-mythic mountains, medieval churches, and agrarian rhythm, could activate all three registers simultaneously. For some émigrés, encountering his works at Venice constituted a symbolic homecoming, where the homeland appeared not as a political territory but as an affective synthesis of history, faith, and labour. Rather than resisting the aims of early Soviet cultural diplomacy, these responses exemplify what Pattie calls the creative tension of diasporic identity characterised by an interplay of ethnic, national, and transnational belonging.58

If Saryan’s contribution to Venice in 1924 offered one of the first Soviet framings of Armenian modernity, his subsequent trajectory traced the evolving relationship between artistic agency, national culture, and the emerging mechanisms of Soviet cultural diplomacy. Although officially nominated by Moscow’s special committee, his role in assembling the Armenian grouping appears to have extended beyond bureaucratic compliance. Scholars have suggested that Saryan personally facilitated the inclusion and transport of works from Armenia, an involvement that would explain the presence of artists such as Vardges Sureniants and Panos Terlemezian, figures either deceased or living in exile and not formally attached to Soviet institutions.59 Their appearance in Venice introduced an unplanned genealogy of Armenian art that spanned pre-revolutionary, diasporic, and Soviet contexts, projecting a continuity that the organisers themselves may not have explicitly intended but that the pavilion nonetheless reframed through a socialist lens.

This idea of continuity was further reinforced by Saryan’s recent portraits of the poet Yeghishe Charents (1923), the actress Anna Humashyan (1923), and the statesman Ashot Hovhannisian (date unknown). Together, these works formed a civic pantheon of modern Armenian culture. Displayed alongside landscapes such as Midday Silence and Armenia, they articulated a visual rhetoric of cultural renewal refracted through the new ideological order. Saryan’s agency, though exercised within official parameters, reflects not dissent but negotiation: an adaptive process of working through the system to cultivate national art within the state’s sanctioned pluralism.

Committee records confirm that Saryan was one of three artists officially present in Venice, alongside Alexandra Exeter and Petr Konchalovskii.60 Granted a monthly stipend, travel expenses, and per diem payments, he occupied a privileged position among Soviet exhibitors, underscoring his dual status as both representative and beneficiary of the state’s federative vision. The arrangement exemplified a pattern of mutual instrumentalisation: Saryan offered an image of Armenian cultural vitality, and the state, in turn, codified that vitality as evidence of its ideological success. This collaboration was quickly formalised. On Kogan’s favourable recommendation to the head of Armenian Sovnarkom, S. L. Lukashin, Saryan was promised a purpose-built house-studio in Yerevan, and, within a year, awarded the title of People’s Artist of the Armenian SSR.61 Between 1926 and 1928, he undertook a state-sponsored residency in Paris, exhibiting with the Society of Armenian Artists Living in France (known as ‘Ani’) and holding his first solo exhibition at the Galerie Charles-Auguste Girard, supported in part by Armenian émigré networks.62 These activities extended the circuits of cultural exchange set in motion at Venice, blurring the boundaries between Soviet diplomacy and diasporic agency.

The 1924 Soviet pavilion thus encapsulates the improvisational pluralism of early Soviet cultural diplomacy. Its financial and critical reception was modest, with only seventeen paintings and graphic works sold, a return that scarcely covered administrative costs.63 European critics, divided along ideological lines, viewed the display as too conservative for the avant-garde and too modern for the traditionalists, while Soviet officials regarded it as an incomplete realisation of their political and aesthetic aims.64 Yet this very indeterminacy made the pavilion historically revealing. Whether or not such outcomes were fully intended, the display generated a contingent, dialogic field of meaning, opening channels between centre and periphery, homeland and diaspora, and between Soviet institutions and local initiative.

In retrospect, the 1924 exhibition can be seen as a provisional articulation of the multiethnic ideal the Soviet Union was beginning to codify. Officially, the pavilion presented a unified image of Soviet culture, avoiding explicit classification by republic or ethnicity. In practice, however, the prominence of six Armenian artists and the curatorial focus on Saryan signalled a nascent ethno-national profiling within what was ostensibly a collective enterprise. As art historians Olena Kashuba-Volvach and Maryna Drobotjuk have shown, the 1928 edition of the Biennale introduced the first explicitly designated Ukrainian section within the Soviet pavilion—an ad hoc but decisive step toward the institutionalisation of this pluralism.65 By the early 1930s, these representational strategies had become systematic, maintaining the outward form of korenizatsiia while increasingly consolidating Moscow’s interpretative authority.66

Conclusion

This article has revisited the 1924 Soviet section at the Venice Biennale through the lens of Martiros Saryan’s participation, treating a largely overlooked exhibition as a key site in the formation of early Soviet cultural diplomacy. By foregrounding one artist’s position within this network, it has shown that the early Soviet experiment in international representation was shaped not by ideological uniformity, but rather negotiation and collaboration. Saryan’s portrayal of Armenia’s landscape and cultural life, and his engagement with both state institutions and diasporic publics, reveal a mode of artistic practice that was neither oppositional nor merely compliant, but co-constitutive of the new political and ideological order.

Saryan thus emerges not only as a painter of Armenian land and life, but as a figure through whom the entanglement of art and power in the early Soviet period becomes legible. His trajectory during the NEP years illustrates how artistic agency could operate through pragmatism and adaptation, and how national culture was sustained within, rather than outside, the mechanisms of Soviet governance. To regard him solely as a national artist is to overlook the reciprocal strategies that linked individual ambition to institutional purpose, and the extent to which the early Soviet state depended on such negotiated partnerships to project its federative ideals abroad. The 1924 pavilion, in turn, stands as evidence of a brief but formative moment when Soviet cultural diplomacy remained experimental and contingent, and when multiplicity itself functioned as a mode of political imagination.

More broadly, this study underscores the need to read early Soviet exhibitions as spaces of agency as well as representation—sites where artists could mediate between local, diasporic, and international publics. It also points toward productive directions for further research: the role of diaspora-facilitated exhibitions in the interwar period; the shifting positions of artists who have since become emblematic of post-Soviet national culture; and the broader question of how cultural actors navigated, shaped, and sometimes redefined the early Soviet project. Together, these avenues invite a more fluid understanding of early Soviet cultural diplomacy, one defined by hybridity, dialogue and interdependence rather than by binaries of centre and periphery, resistance and compliance.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Dr Maria Mileeva for her invaluable feedback on this work when I first submitted it is as an MA essay. I am also grateful to the editors of Immediations and the anonymous peer reviewers for their thoughtful feedback and generous engagement with my work.

Citations

[1] ‘Надо сказать, что наши художники были отмечены публикой, все отмечали национальный характер наших работ.’ Martiros Saryan, Iz moei zhizni, (Izobrazitel’noe iskusstvo, 1985), 228. All translations are my own unless otherwise noted. The spelling ‘Saryan’ is used throughout this article, in accordance with the Eastern Armenian pronunciation, rather than ‘Sarian’ (Russian-language transliteration).

[2] XIV Esposizione Internazionale d’Arte della Citta di Venezia took place between April and October 1924. The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), also known as the Soviet Union, was founded in December 1922 and existed until 1991.

[3] Saryan, Iz moei zhizni, 216.

[4] Jonathan Haslam, The Soviet Union and the Struggle for Collective Security in Europe, 1933–39 (St. Martin’s Press, 1984), 11; Pevsner, ‘Pavil’on SSSR na venezianskoi biennale 1924 goda’, 233. The pavilion closed from 1938 to 1954 and from 1978 to 1980. After the dissolution of the USSR in 1991, the Russian Federation assumed control. It withdrew in 2022, following the invasion of Ukraine, and was absent again in 2024.

[5] New Economic Policy (NEP) replaced centralised planning that predominated during the Civil War (1918-1922). For more information, see Lewis H. Siegelbaum, Soviet State and Society between the Revolutions, 1918-1929, (Cambridge University Press, 1992), 135-224.

[6] The Treaty of Rapallo, signed on 16 April 1922, led to the 1922 Berlin show at the Van Diemen Gallery in October. See Ulrich Schmid, ‘What did “Russian” mean in the Early Twentieth Century?’, in 100 Years On: Revisiting the First Russian Art Exhibition of 1922, ed. Isabel Wünschen and Miriam Leimer (Böhlau, 2022), 21. The pavilion closely mirrored the artist selection for Berlin, albeit on a larger scale. Saryan exhibited two paintings in Berlin and ten in Venice, the second largest after the painter Petr Konchalovsky. Other early exhibitions included The Exhibition of Russian Painting and Sculpture at the Brooklyn Museum in 1923 and The Russian Art Exhibition at the Grand Central Palace in 1924 in New York.

[7] Ol’ga, Pevsner, ‘Pavil’on SSSR na venezianskoi biennale 1924 goda. Rekonstryktsia vystavki’, Iskusstvoznania, no. 4 (2022), 220.

[8] Avetik Isahakyan, ‘Armenian Paintings’, Hayrenik 5 (August 1924), reproduced in Alexandr Kamenskii and Sh. G. Khachatryan, eds., About Saryan: Pages of Art Criticism. Review of Contemporarie, (Sovetskii khudozhnik, 1980); partially reproduced in Saryan, Iz moei zhizni, 235.

[9] Rossiiskaia Kommunisticheskaia Partiia (Bolshevikov), Dvenadtsatyi s’ezd RKP(b): Stenograficheskii otchet (Gosudarstvennoe izdatel’stvo, 1923), 664.

[10] Yuri Slezkine, ‘The USSR as a Communal Apartment, or How a Socialist State Promoted Ethnic Particularism’, Slavic Review 53, no. 2 (Summer 1994), 415.

[11] Boris Ternovets, Padiglione dell’U.R.S.S.: Supplemento al catalogo ufficiale illustrato. XIV Esposizione Internazionale d’Arte della Città di Venezia – 1924 (Premiate Officine d’Arti Grafiche C. Ferrari, 1924).

[12] Maike Lehmann, ‘Apricot Socialism: The National Past, the Soviet Project, and the Imagining of Community in Late Soviet Armenia’, Slavic Review 74, 1 (Spring 2015): 9-31; Susan Pattie, ‘Longing and Belonging: Issues of Homeland in Armenian Diaspora’, Political and Legal Anthropology Review 22, no. 2 (November 1999): 80-92.

[13] ‘Works’, M. Saryan House-Museum, accessed 7 October 2024. For a similar sentiment, see Alexandr Kamensky, Martiros Saryan: Paintings, Watercolours, Drawings, Book Illustrations, Theatrical Designs (Sphinx Press, 1988); Vera Razdol’skaia, Martiros Saryan: 1880-1972 (Sovetskii khudozhnik, 1998).

[14] Vivian Benett, ‘The Russian Presence in the 1924 Venice Biennale’, in The Great Utopia: The Russian and Soviet Avant-Garde, 1915-1932 (Guggenheim Foundation, Rizzoli International Publications, Inc., 1992), 468; Matteo Bertele, ‘Russian Artists at the Venice Biennale: From Stateless Pavilion to Abandoned Pavilion (1920-1942)’, in Russian Artists at the Venice Biennale, 1895-2013, ed. Nikolai Moloko (Stella Art Foundation, 2013), 45.

[15] Maria Mileeva, ‘Import and Reception of Western Art in Soviet Russia in the 1920s and 1930s: Selected Exhibitions and Their Role’ (PhD Dissertation, The Courtauld Institute of Art, University of London, 2011); Peter Burke, Eyewitnessing: The Uses of Images as Historical Evidence (Reaktion, 2001).

[16] Narkompros was founded in 1917 and headed by Lunacharskii until 1929. See Sheila Fitzpatrick, The Commissariat of Enlightenment, Soviet Organisation of Education and the Arts Under Lunacharsky October 1917-1921, (Cambridge University Press, 1970).

[17] Anatoly Luncharaskii and Yuvenal Slavinskii, ‘Tezisy khudozhestvennogo sektors NKP i TsK RABIS ob osnovakh politiki v oblasti iskusstva’, Isskustvo, no. 1 (1921), 21. The text is reproduced in English in John E. Bowlt, ed., Russian Art of the Avant-Garde: Theory and Criticism: 1902-1934 (The Viking Press, 1976), 182-185. Slavinskii was the president of the Central Committee of All-Russian Union of Artist Workers (Soyuz rabotnikov iskusstv, VSERABIS).

[18] The Bolshevik government introduced the Plan for Monumental Propaganda (April 1918) that aimed to replace the Tsarist monuments with new Soviet symbols. Vladimir Lenin, as the leader of the Party and its main theorist, had argued that in the process of the construction of socialism, the working class should use all the progressive elements of the past. A. Gak, ‘V. I. Lenin i razvitie mezhdunarodnykh nauchnykh sviazei Sovetskoi Rossii v 1920-1924 gg.’, Voprosy istorii, no. 4 (1963); M. Kharlamov (ed.), Leninskaia vneshniaia politika Sovetskoi strany, 1917-1924 (Nauka, 1969).

[19] RAKhN changed its name to the State Academy of Artistic Sciences (GAKhN) in 1925. However, for the purposes of this article, I will use RAKhN in reference to the Academy. Lunacharskii also worked in the Sociological Department. See Nikolai Plotnikov, ‘100 Years of GAKhN. Artistic Research Between Art and Science’, Studies in East European Thought 75 (2022): 213-214.

[20] Plotnikov, ‘100 Years of GAKhN’, 215.

[21] Pevsner, ‘Pavil’on SSSR na venetsianskoi biennale 1924 goda’, 238.

[22] Other artists who were members of the department include Robert Falk and Kazimir Malevich. The State Institute of Artistic Culture (Gosudarstvennaia Academia Khudozhestvennykh Nauk, INKhUK) had a similar programme being developed by Aleksandr Gabrichevskii and Kandinsky.

[23] Maria Silina, ‘Anatoly Bakushinsky’s Projects in Art Studies and Knowledge Production at the State Academy of Artistic Sciences’, Studies in East European Thought 75 (2023), 305-313.

[24] After 1924, Ternovets helped organise the Soviet section at the 1925 Paris Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs, the 1927 Mostra Internazionale delle Arti Decorative in Monza and was on the committee for the USSR Pavilion at the XVI Venice International Art Exhibition in 1928. In addition to representatives from Narkompros, RAKhN, GMNZI and Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries (VOKS), the special committee of the Soviet Section of the Fourteenth International Exhibition in Venice included representatives from the Art Section of the Chief Directorate of Political Education (Glavpolitprosvet), the Art Section of the Chief Administration for Scientific, Artistic and Museum Institutions under Narkompros (Glavnauka), VSERABIS, and art critic Yakov Tugenkhol’d. The number of state institutions involved in the organisation of the Soviet section represents the significant role of the Soviet display in the highly competitive international context of the Biennale.

[25] Boris Ternovets, ‘Sotrudnikam museia’, letter, 29 June 1924, Venice, reproduced in L.S. Aleshina and N. V. Yavorskaia eds., B.N. Ternovets: pis’ma, dnevniki, stat’i (Sovetskii khudozhnik, 1977), 151-154.

[26] Ternovets, ‘Sotrudnikam museia’, 148-149.

[27] Ternovets, ‘Sotrudnikam museia’, 151-152.

[28] Pevsner, ‘Pavil’on SSSR na venetsianskoi biennale 1924 goda’, 220.

[29] Pevsner refers to the works as being part of the lineage of ‘Jack (or Knave) of Diamonds’, which was a circle of avant-garde artists in late Imperial Russia, influenced by French modernism and seeking to provoke the art establishment. See John E. Bowlt, ‘Neo-Primitivism and Russian Painting’, The Burlington Magazine 116, no. 852 (1974): 133-140. In 1912 and 1913 Kuznetsov undertook expeditions through the Trans-Volga steppes and Central Asia, including present-day Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan.

[30] Pevsner, ‘Pavil’on SSSR na venetsianskoi biennale 1924 goda’, 222-223.

[31] ‘Его картины являются ярким выражением такого сильного и самобытного темперамента, что […] заслуживают большого внимания с точки зрения исканий современного искусства. Есть в Сарьяне нечто, напоминающее Матисса. Это характерные черты ориентализма. Впрочем, Сарьян отличается от последнего своей исключительной, более непосредственной и ясной силой, другими словами, меньшей рассудительностью.’ Giuseppe Sprovieri, ‘Armenian Artist Martiros Saryan’, Il Mondo, 24 August 1924. Reprinted in Russian in Saryan, Iz moei zhizni, 228-232.

[32] Boris Chukhovich, ‘“Non-national Artists” and “National Art”: On the Exclusivity of the “Inclusive” terms of Soviet Aesthetics’, Bulletin of IICAS 29 (2020): 97- 99.

[33] Ternovets, Padiglione dell’U.R.S.S.; Boris Ternovets, ‘La Section Russe à l’Exposition Internationale de Venise’, La renaissance de l’art francais et des industries de lux (October 1924), 543.

[34] Ternovets, ‘La Section Russe à l’Exposition Internationale de Venise’, 543.

[35] Pevsner, ‘Pavil’on SSSR na venetsianskoi biennale 1924 goda’, 220.

[36] Saryan participated in key early Symbolist exhibitions such as the Scarlet Rose (1904), Blue Rose (1907), and Golden Fleece (1908). He also exhibited with the World of Art group.

[37] In Egypt, he travelled to Cairo, Giza, Memphis, and Luxor; in the Ottoman Empire, to Constantinople; and in Persia to Enzeli, Rasht, Qazvin, and Tehran. Saryan, Iz moeiei zhizni, 27.

[38] John E. Bowlt, ‘The Blue Rose: Russian Symbolism in Art’, The Burlington Magazine 118, no. 881 (August 1976): 573.

[39] M. Voloshin, ‘M.S. Saryan’, Apollon, no. 9 (November 1913):19.

[40] ‘Статья Ваша обо мне, по-моему, великолепная, я ее несколько раз перечитывал и читал как отдельное произведение, основанное на истине. Я очень рад, что вы пишете о том, что есть, и Ваша наблюдательность меня, признаться, трогает.’ ‘Letters’, M. Saryan-House Museum, accessed 10 October 2025.

[41] Saryan, Iz moeiei zhizni, 27. Saryan also travelled to Haghpat, Sanahin, Sevan, and Yerevan.

[42] Pre-revolutionary private collections of modern western art, such as the famous collections of Sergei Shchukin and Ivan Morozov, were known to many artists in turn-of-the-century Moscow and played a significant role in the development of the avant-garde in the Russian Empire.

[43] Pevsner, ‘Pavil’on SSSR na venetsianskoi biennale 1924 goda’, 265, 268. While Yerevan (1924) has been exhibited at the National Gallery of Armenia in Yerevan, its present location remains unknown.

[44] Chukhovich, ‘“Non-national Artists” and “National Art”’, 99-105.

[45] Terry Martin, The Affirmative Action Empire: Nations and Nationalism in the Soviet Union, 1923-1939 (Cornell University Press, 2001), 12. See also Jeremy Smith, Red Nations: The Nationalities Experience in and after the USSR (Cambridge University Press, 2013), 24.

[46] Martin, The Affirmative Action Empire, 23.

[47] Mark Bassin and Katriona Kelly, eds., Soviet and Post-Soviet Identities (Cambridge University Press, 2012), 24.

[48] Martin, The Affirmative Action Empire, 23.

[49] Harsha Ram, ‘Peripheral Modernisms: Transnational Modernity in the Caucasus’, in Scale and the Rise of the Networked City: Regional Modernisms and the New Geography, ed. Yael Rice and Simon Faulkner (Manchester University Press, 2016), 148.

[50] Saryan, Iz moei zhizni, 214. During this time, Saryan helped found the State Museum of Archaeology, Ethnography and Fine Arts, the Yerevan Art School, and the Association of Fine Arts Workers, recruiting artists and teachers from across the republic and diaspora.

[51] The Garni Temple is a first-century CE Greco-Roman temple in Armenia, built by King Tiridates I for the sun god Mihr. It is Armenia’s only surviving pagan temple, functioning as a symbol of its pre-Christian past.

[52] Horovel, also called ‘gutani yerg’ (‘plough song’), is an Armenian folk song that served as a work song, sung by peasants while preparing fields for cultivation. On Armenia’s vernacular architecture, see Suzanne Monnot, ‘Vernacular Architecture in Armenia, from Travellers’ Accounts, in the Western Context, from the 17th Century to the Present Day’, Scientific Journal NRU ITMO. Series: Economics and Environmental Management 4, no. 51 (2021):116.

[53] Ronald Grigor Suny, The Revenge of the Past: Nationalism, Revolution, and the Collapse of the Soviet Union (Stanford University Press, 1993), 85-124; Looking Toward Ararat: Armenia in Modern History (Indiana University Press, 1993), 151-186.

[54] ‘About Avetik Isahakyan’, House-Museum of Avetik Isahakya, accessed 17 April 2025.

[55] ‘некоторые картины Сарьяна—настоящие шедевры, как, например, «Армения», которая является синтезом нашей родины’; ‘И вы удивляетесь, каким чудом, каким неведомым таинством посреди безбрежного океана российских просторов появляются на свет армяне, подобные Микаелу Налбандяну, Рафаелу Патканяну и Мартиросу Сарьяну, армяне до мозга костей, страстные «армянопоклонники», ум и сердце которых — Армения и осмысляющий ее армянский народ.’,Isahakyan, ‘Armenian Paintings’, 235. M. Saryan House-Museum accessed 20 April 2025.

[56] Lehmann, ‘Apricot Socialism’, 12-13, 20-21.

[57] Pattie, ‘Longing and Belonging’, 81-83.

[58] Pattie, 81. Drawing on Robin Cohen’s book Global Diaspora: An Introduction (Routledge, 1997), Pattie adopts Cohen’s influential view of diaspora as a creative rather than deficit condition, in which ‘the tension between ethnic, national, and transnational identity is often a creative, enriching one’.

[59] Pevsner, ‘Pavil’on SSSR na venezianskoi biennale 1924 goda’, 220.; Levon Chookaszian, ‘Panos Terlemezian’, Armenian Studies Program, University of Michigan, accessed 21 April 2025.

[60] RGALI, f. 941. Op. 15. Ed. Khr. 54. 1.3; cited in Pevsner, ‘Pavil’on SSSR na venezianskoi biennale 1924 goda’, 243.

[61] Saryan, Iz moei zhizni, 243.

[62] While the memoir does not name specific individuals, Saryan wrote that these connections were instrumental in facilitating the show. Saryan, Iz moei zhizni, 253.

[63] Pevsner, ‘Pavil’on SSSR na venezianskoi biennale 1924 goda’, 258. Pevsner calculates that total sales, including decorative arts, amounted to 54,900 lira or 5,242.06 rubles. After the Biennale’s standard 15 per cent deduction and RAKhN’s additional 10 per cent administrative fee, only 4,455.75 rubles remained for payment to artists—an amount that, against the project budget of 24,000 rubles, barely covered postal expenses.

[64] Pevsner, ‘Pavil’on SSSR na venezianskoi biennale 1924 goda’, 259. While Soviet commentators, including Lunacharskii, noted several positive responses from foreign press, such as those of the Italian daily Corriere della Sera and The Times in the UK, overall attitudes remained unsatisfactory. See Anatolii Lunacharskii, ‘O russkoi zhivopisi (Po povody venzianskoi vystavki)’, Izvstiia (October 1924), 4.

[65] Espozione Internazionale d’Arte della Città di Venezia. Catalogo Generale: XVI Biennale (1928), (Premiate Officine d’Arti Grafiche C. Ferrari, 1928); Espozizione Internazionale d’Arte della Città di Venezia. Catalogo Generale: XVIII Biennale (1932) (Premiate Officine d’Arti Grafiche C. Ferrari, 1932).

[66] Olena Kashuba-Volvach and Maryna Drobotiuk, ‘In the Shadow of Russia: Ukrainian Art at the XVI Venice Biennale of 1928’, in In the Eye of the Storm: Modernism in Ukraine, 1900-1930s, ed. Konstantin Akinsha (Thames and Hudson, 2022), 103.