£65

Oxford University Press

2022

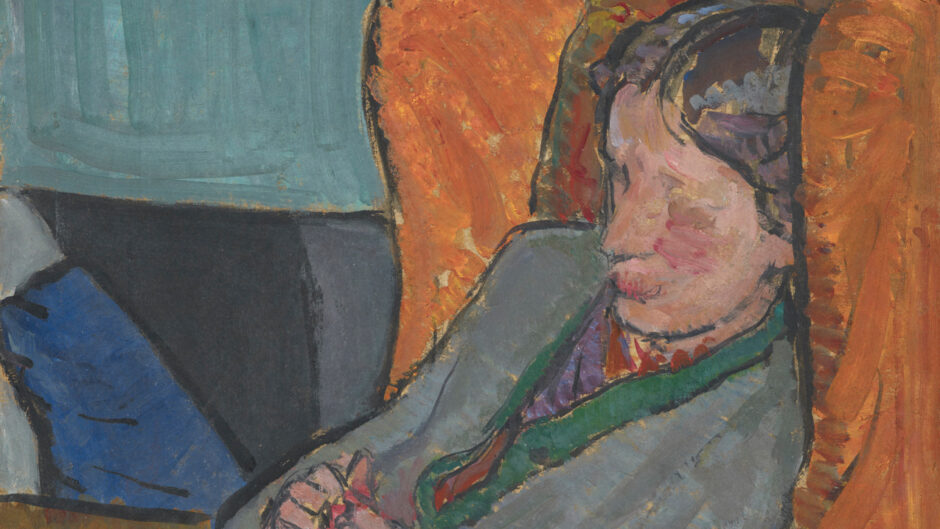

‘Knitting is the saving of life’.[1] Written in 1912, Virginia Woolf’s words warmly compliment Vanessa Bell’s portrait of the writer from the same year (Fig. 1). As Woolf’s features disintegrate into peachy smudginess, her knitting is clearly articulated, held in thickly outlined fingers. The knitted textile, rendered in vibrant impasto, contrasts with the painting’s otherwise subdued, matt texture and glimpses of chalky ground. This, it seems, is as much a portrait of the process of craft as it is of Woolf herself – perhaps even more so.

Amy Elkins opens the first chapter of Crafting Feminism, therefore, with this image, approaching Woolf not as a writer but as a craftswoman. Venturing further than previous studies of Woolf, which have merely identified the needlework motifs throughout her novels, Elkins positions the process of crafting, not its product, at the heart of the feminist creation of Woolf’s texts – both in the physical production of typesetting, printing, and binding, and in the way Woolf’s themes, narratives, structures, and characters engage with a broader history of women’s making.

Therefore, at the heart of Crafting Feminism is a compelling research methodology founded in craft practice. Structuring Crafting Feminism through collaging literary criticism chapters amongst corresponding ‘Techne’ chapters, Elkins demonstrates this methodology in practice. Elkins’s ‘Techne’ chapters recount her experiences of learning, teaching or observing the crafts she encounters in literature, disrupting disciplinary boundaries between art history, literary criticism, and art practice. Thus, this review finds its focus around the innovative interruption of these ‘Techne’ chapters and their value to feminist art historical scholarship.

Elkins begins with a consideration of the fragmentary nature of typesetting, leading neatly into her opening chapter on Woolf’s feminist writing and printing process. Through Elkins’s experiences of wet collodion photography, Techne II touches on Woolf’s relationship with her great-aunt, the photographer Julia Margaret Cameron, and thus the experienced inheritance of craft between women as an alternative archive. This guides Elkins to consider the woollen objects owned by the poet H. D. (Hilda Doolittle) and how H. D. therefore inherited a ‘Needlecraft Feminism’ through these crafted objects.[2] Craft, then, is not simply a process, but a transmission of knowledge between women. ‘Techne III: Inky Depths’ details Elkins’s ink-making, from sourcing different black pigments to experimenting with how they apply to paper. This reveals a deeply felt understanding of the practice which underlies her following chapter on the Caribbean poet and painter Lorna Goodison and the resonances that ink-making has with aspects of Black history in Goodison’s womanist poetry. Employing a powerfully personal tone in these ‘Techne’ chapters, Elkins engages evocatively with the affective turn in feminist methodology and does not shy away from the rhetorical importance of craft’s emotivity.[3]

Transitional in nature, there are moments when these Techne chapters try to practice too much. ‘Techne II: Passed Down’, for example, contends with both wet collodion photography and needlecrafts, creating a lack of focus and a disjunction, disrupting the attempt at a seamless movement between literary criticism chapters. It would serve Elkins well in these moments to pay greater attention to the medium specificity of the crafts in each chapter to avoid these lapses in focus which generalise ‘craft’ and therefore tend to universalise women’s experiences of craft as a culture of making. It is, perhaps, not enough that Elkins recognises the broad category of craft as a productive framework for intersectional feminist art histories, addressing how working class, queer, Black, indigenous, and gendered voices have all been marginalised in different ways through the marginalisation of craft and craftspeople in art history and literary criticism.

Indeed, Crafting Feminism sometimes slips into attributing a radically feminist quality to all women’s craft practice where critical readings suggest otherwise. Elkins poses the photographer Julia Margaret Cameron as Woolf’s feminist foundation although Cameron was deeply rooted in conservative, domestic ideals of womanhood. In both the idealised imagery of maternal family units, and the domestic production of Cameron’s photographs as if they were just another element of women’s household labour, Cameron reproduced the bourgeois Victorian fantasy of women’s domestic maternal role.[4] Furthermore, Elkins characterises H. D.’s needlepoints as deeply modernist, employing a medium that ‘insists on a subversive feminist practice’.[5] However, in their style and floral and religious subjects, her works more strongly resemble the patterns for Berlin wool work that was mass-produced in women’s magazines and criticised by contemporary feminist craftswomen, than any modernist needlepoint. Crafting Feminism would have benefitted from a ‘Techne’ chapter centred around practicing needlepoint – a process which, in practice, is repetitive and often unstimulating. This would have aided an understanding of why early twentieth century feminists criticised this craft practice in particular, therefore establishing a medium-specific nuance in a feminist distinction between empowering craft and oppressive toil rather than assuming that all craftwork undertaken by feminists is, inherently, empowered.

Yet, when done well, these ‘Techne’ provide compellingly sensitive and generative results which demand the need for practice-based research and demonstrate the promise of such approaches. This is particularly evident in ‘Techne IV: Patchworks’ in which Elkins utilises collaging to explore the theoretical importance that these processes have to feminist poetic practice. Elkins demonstrates that collage and patchwork’s specific ability to draw various elements together – like the intersections of different aspects of identity – allows for differences to exist in complex unity in craft just as they do within people. Therefore, through an attention to the medium-specificities of their processes, Elkins brilliantly establishes that collage and patchwork are formally intersectional media that resist reductive arguments around identity. Elkins’s focus on collage and patchwork in the second half of Crafting Feminism excels in its varied examination of the uses of collage in feminist literature, from ‘Techne IV’ to a detailed examination of craft’s generative intersections with the digital humanities through a study of Kabe Wilson’s Olivia N’Gowfri – Of One Woman or So (2009-2014), a satirical literary project which re-arranged the letters of Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own into a new text concerned with the experiences of Black women in higher education today. In this second half of the book, Elkins finds her feet and makes an outstanding case for medium-specific practice-based research.

Crafting Feminism will, therefore, delight any art historian, feminist scholar, and literary critic excited by the recent energy in craft-studies evident in Daniel Fountain’s Crafted with Pride (Bristol: Intellect, 2023) and Anthea Black and Nicole Burisch’s The New Politics of the Handmade (London: Bloomsbury, 2020). Elkins makes a compelling and creative contribution and, following Crafting Feminism’s project ‘to loosen the binding of the academic monograph’, perhaps we too shall find new ways of working to re-ink, re-print, re-collage, and re-stitch feminist research.

Citations

[1] Virginia Stephen to Leonard Woolf, 5 March 1912, in The Flight of the Mind: The Letters of Virginia Woolf, vol. 1, ed. Nigel Nicolson (London: Hogarth Press, 1975), 491

[2] Amy Elkins, Crafting Feminism from Literary Modernism to the Multimedia Present (Oxford: OUP, 2022) 81-82.

[3] See Sarah Ahmed The Cultural Politics of Emotion (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2004) for greater discussion of the affective turn in feminism.

[4] See Carol Armstrong’s ‘Cupid’s Pencil of Light: Julia Margaret Cameron and the Maternalisation of Photography’, October 76, (1996), 114 – 141, for greater discussion of the matriarchal but not feminist nature of Cameron’s photographic practice.

[5] Elkins, 108.