Architect, conservationist, and artist Jorge Otero-Pailos recently perfected a cutting-edge technique to restore stone buildings disfigured and threatened by pollution particles. He applies latex so as to peel off pollution from walls, preserving the building from unwanted erosion, and he thus obtains an authentic one-to-one-scale facsimile of the facade, which he later exhibits in art museums. Otero-Pailos’s revolutionary technique was used in 2009 to preserve the Ducal Palace in Venice, and more recently the surface of Trajan’s Column (2015) and the walls of Westminster Hall (2016). Otero-Pailos reminds us that the material source of the very existence of and need for architectural preservation is pollution (among other natural or man-induced factors): ‘Had there been no pollution, I sincerely doubt we would have preservation as we know it’.[1] His method is unprecedented as it allows the conservation of both wall and dirt, leaving the cleaned wall entirely undamaged and capturing the dirt. After the architectural practice of cleaning the facade has been enacted, the trace of pollution is exhibited in museums, becoming a politicised, anthropological artefact that invites humankind to acknowledge that pollution in the shape of carbon particles has become part of their palpable cultural heritage.

Otero-Pailos was born in 1971 in Madrid, Spain. Now based in New York, he is also an architect and conservationist by profession. Drawing from his formal training in architecture and preservation, Otero-Pailos’s art practice deals with memory, culture, and transitions, and invites the viewer to consider buildings as powerful agents of change. The title of his ambitious project, just described—The Ethics of Dust—alludes to Ruskin’s instructional manual on geological topics, originally written for a young female audience in 1866.[2] Otero-Pailos’s polymorphic architectural interventions, in the shape of latex casts turned into artworks, question our ethical responsibilities in environmental preservation. In doing so, they challenge the disciplines of architecture and art. Creating a print (which is also, literally, a cast) that belongs to the exceptional pictural category of the vera icon implies that the translucent latex sheet represents the building, but at the very same time, it constitutes the building itself, since dust is held captive as a trace, recording hundreds of years of coloured particles. The Ethics of Dust series thus annihilates the very distance between the represented object and its actual existence, both being present in a new medium that offers a perfect adherence of the figurative to the literal.

Ruskin saw in dust an index of time in the Peircian sense, as I will demonstrate. I propose that pollution can be thought of in terms of the ‘golden stain[s] of time’, which Ruskin praises as essential to architecture’s meaning in The Seven Lamps of Architecture (1849).[3] I argue not only that Ruskin is key to interpreting the work of Otero-Pailos, but that seen through the translucent film of Otero-Pailos’s latex casts Ruskin himself appears in a new light, and this will allow me to clarify the long-presumed but little-understood complementariness of Ruskin’s Gothic with the architectural theory of the French architect Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc—in spite of their notoriously opposing attitudes to restoration—and other areas of nineteenth-century architectural aesthetics. I will then analyse how Otero-Pailos furthers Ruskin’s thoughts about surface decay and about the passing of time, enabling for the first time the capture of immaterial dust in a perfect plastic form.

‘Of the many broad divisions under which architecture may be considered, none appears to me more significant than that into buildings whose interest is in their walls, and those whose interest is in the lines dividing their walls’.[4] Of all manufactured architectural surfaces, the wall, for Ruskin, is the palimpsest upon which to read the history of men, and upon which to attach all possible attention. In ‘The Lamp of Power’, he sees in every wall an opportunity to read what time has to tell men:

And it is a noble thing for men … to make the face of a wall look infinite, and its edge against the sky like an horizon: or even if less than this be reached, it is still delightful to mark the play of passing light on its broad surface, and to see by how many artifices and gradations of tinting and shadow, time and storm will set their wild signatures upon it.[5]

Influenced by Ruskin’s search for truth and authenticity, William Morris founded in 1877 The Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings on the premise that each layer of a building’s history should be retained. There arose in men’s minds, Morris and the architect Phillip Webb wrote,

the strange idea of the Restoration of ancient buildings; and a strange and most fatal idea, which by its very name implies that it is possible to strip from a building this, that, and the other part of its history—of its life that is—and then to stay the hand at some arbitrary point, and leave it still historical, living, and even as it once was.[6]

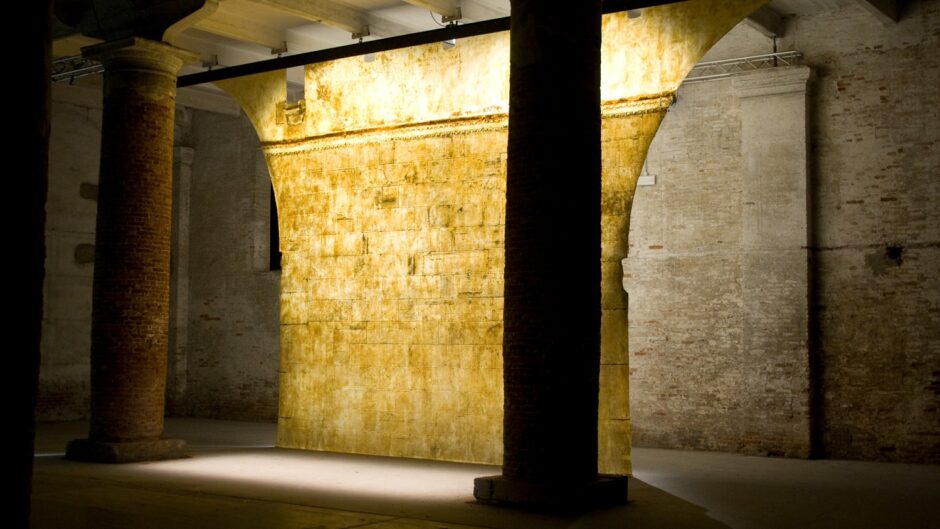

More than one century later, literally stripping layers off from a building so as to observe them has become technologically possible. These layers are composed of a variety of debris left by human activity or weather elements on a worldwide scale (Figs. 13.1 and 13.2). It is worth wondering what pollution in a broad sense would tell us about our social, cultural, industrial, and ethical past if it were to be preserved as a museum artefact, questioning the relevance of a history of pollution that would be situated at the intersection of architecture, history of art, and literature. Otero-Pailos’s work addresses these questions, and shares with Ruskin’s a heightened sensitivity to the importance of surfaces as bearing the deposit of time, encompassing both natural and human legacy.

Before pollution stifled our planet, as surprising as it may seem nowadays, it would sometimes bring about admired, and even desired effects.[7] The soot that stuck on stone buildings was seen as the genuine mark left by modernity, visible in the rising industrial capitals of the nineteenth century. Some architectural conservators acknowledged the cultural value of pollution and it is, paradoxically, as one of the fathers of conservation that Ruskin also happened to praise the black layer of dust as testifying to the passage of time. Ruskin famously, in The Storm-Cloud of the Nineteenth Century (1884), blamed the devil of industrialism while scanning the ‘plague-clouds’ and ‘plague-winds’, the source of the ‘Manchester devil’s darkness’ which blanched the sun and choked mankind. He was horrified by the effect of industrial soot on the built environment then.[8] However, in a different context, thirty-five years before his famous and visionary depiction of plague clouds, Ruskin seemed to accept pollution and elemental residue as bestowing some value and grandeur to buildings. As Courtney Skipton Long states, he was ‘an advocate of natural senescence’ in architecture, which includes the accumulation of dust, soot, dirt, chemicals, and the natural process of decay and erosion of elements.[9] Ruskin viewed the accretion of dirt as a positive component of a structure. To observe the amassing of dirt and grime on a building’s facade was to know that the structure was able to endure the passage of time, and able to bear witness to that passage in the form of a film on its surface. He thus found in the stained surfaces of buildings the welcome traces of the process of time. As it clad some noble buildings in a sombre veil, notably the Ducal Palace in Venice, which he considered the ‘central building in the world’, he protested any attempt to remove the evidence of historical change.[10] Ruskin thus wrote in The Seven Lamps that he respected pollution as a visible and therefore reliable index of time, dust and soot granting historical significance to the buildings they happened to stain:

Do not let us talk then of restoration. The thing is a Lie from beginning to end. You may make a model of a building as you may of a corpse, and your model may have the shell of the old walls within it as your cast might have the skeleton, with what advantage I neither see nor care: but the old building is destroyed, and that more totally and mercilessly than if it had sunk into a heap of dust, or melted into a mass of clay: more has been gleaned out of desolated Nineveh than ever will be out of re-built Milan. But, it is said, there may come a necessity for restoration! Granted. Look the necessity full in the face, and understand it on its own terms. It is a necessity for destruction. Accept it as such, pull the building down, throw its stones into neglected corners, make ballast of them, or mortar, if you will; but do it honestly, and do not set up a Lie in their place. And look that necessity in the face before it comes, and you may prevent it. The principle of modern times, (a principle which, I believe, at least in France, to be systematically acted on by the masons, in order to find themselves work, as the abbey of St. Ouen was pulled down by the magistrates of the town by way of giving work to some vagrants) is to neglect buildings first, and restore them afterwards. Take proper care of your monuments, and you will not need to restore them. [11]

Ruskin was aware of the paradox according to which to preserve something means to change it; to use architect Mark Wigley’s phrase, ‘the past is always a project’ in the hands of zealous conservators-restorers.[12] At the intersection of discourses on preservation and curatorship, Otero-Pailos shifts a restoration practice into an artistic context, thus producing a truly exceptional artefact. The Ethics of Dust series keeps growing as more buildings are being commissioned for preservation around the world and subsequently treated by Pailos.

Of dust as time stain

The Ethics of Dust series is named after Ruskin’s volume (minus one definite article in the title), itself subtitled ‘Ten Lectures to Little Housewives on the Elements of Crystallization’. It is a didactic text disguised as a mineralogical course addressed to little girls (an alternative to the disenchanted world of science); it incorporates stories of air, dust, stone, stories taken from the Bible, Greek mythology or thoughts inspired by Lucretius’s poem De Rerum Natura (On the Nature of Things); it is a pretext for an ethical discussion oriented by exegesis.[13] Otero-Pailos’s work is constituted by an isomorphic print of pollution (one point in reality corresponds to the same point on the artefact which reproduces reality) isolated from the stone material on which it was deposited. This print of pollution comes from the outer layer that happens to cover the buildings he is commissioned to clean and preserve. Each work is therefore a very thin layer of latex that itself captures a layer of pollution formed over several centuries. The layer of pollution naturally sticks to the supple surface of a gigantic latex sheet which is spread by Pailos on the surface of the building by industrial means. Applying latex onto the stone surface is a cutting-edge technological process invented by the architect. Unlike sanding or other aggressive mechanical or chemical processes (such as acid) that remove a substantial part of the stone’s surface, Pailos’s technique allows him to leave the actual surface of the building unaltered. Another major advantage of latex is that it preserves not only the building itself, but also the dust pattern that is removed, leaving Pailos with a fascinating three-dimensional item that he is then able to exhibit in museums.

The question of building preservation is even more acute in Venice than anywhere else in the world, as Ruskin himself recognised. He advocated that the black layer of pollution that could be seen everywhere in the Most Serene city in the nineteenth century was part and parcel of the essence of Venice, allowing its buildings to record visually the passage of time. Pollution thus created a patina that ended up confirming historic value (which corresponds to the concept of ‘age-value’ as developed in 1903 by Alois Riegl in The Cult of Monuments).[14] In other words, to preserve something is paradoxically to change it, blocking the course of time and thus breaking its natural, and therefore damaging, flow. Ruskin saw in pollution a welcome trace of time: if on the one hand it contributed to mangle the initial project of the architects and builders, on the other hand it paradoxically made us closer to the original thought of the architects by reminding us of the buildings’ venerable age. The question of whether these stains are intrinsic or extrinsic to the material they are attached to is worth asking: do they come from the material itself, being a sign of the material itself, or are they a mere residue of time? Ruskin seems to think they are part of the material, and therefore would object to sanding off the outer layer of buildings. That is why he chose to name pollution stains ‘time-stains’ in The Stones of Venice, and why he describes them as a seemingly everlasting golden layer which captures time in Seven Lamps:

It is in that golden stain of time, that we are to look for the real light, and colour, and preciousness of architecture; and it is not until a building has assumed this character, till it has been entrusted with the fame, and hallowed by the deeds of men, till its walls have been witnesses of suffering, and its pillars rise out of the shadows of death, that its existence, more lasting as it is than that of the natural objects of the world around it, can be gifted with even so much as these possess, of language and of life.[15]

It is specifically the signs of age which give a building character, inscribing onto its surface the seal of time. In the film left on buildings, then, Ruskin describes something almost analogous to the photographic chemical developer, converting black particles into noble traces left by time. If pollution severs us from the original project of architects, it paradoxically enables us to feel closer to their intentions by encapsulating time and even emotions in its walls.[16] The good architect is therefore able to anticipate the process of time in the design of their building. Influenced by Ruskin’s position against building-cleaning, some Venetian curators saw to it that some facades keep their black films, going so far sometimes as to blacken artificially some recently repaired parts to make them more ancient-looking, which would be a lie in Ruskin’s terms. This custom endured until the end of the century, after Camillo Boito published Conservare o Restaurare (Conserve or Restore) in 1893, and declared that Ruskin’s time stains were only traces of ‘extrinsic filth’ not to be confused with real patina. Under Boito’s strong impulse, a number of Venetian palazzi were thus whitened and brushed, including the Ducal Palace that Pailos restored recently in his turn.[17] One might object that Otero-Pailos might be going against Ruskin’s initial view, by removing the carbon particles from the stone surface. Ruskin was never able to see the pollution destroying the facades of the Venetian palazzi in the twentieth century, however, and we don’t know if he would have preferred to see the building go to ruin or to see the process of destruction arrested.

Interestingly, Otero-Pailos’s work thus bridges Boito and Ruskin’s views, which could at first appear as irreconcilable as those of Ruskin and Viollet-le-Duc. Critics generally underline that the two most prominent theorists of the nineteenth century seemed to hold diametrically opposed ideas on the question of architectural restoration. This needs to be nuanced, as both shared much more than is cursorily acknowledged. In fact, a closer look at Ruskin and Viollet-le-Duc’s theories can reveal common ground; common ground to which Otero-Pailos arguably seems to be drawing attention in his latex casts. Viollet-le-Duc saw restoration as being in the service of some allegorical entity, an ideal independent of time—‘The word [restoration] and the thing itself are modern: to restore a building is not to maintain it, repair it, or rebuild it; it is to reestablish it in a complete state that might never have existed at any given moment’.[18] It is true, as David Spurr underlines, that Viollet-le-Duc favours architectonic structure, whereas Ruskin gives greater importance to surface decoration. It also must be kept in mind the fact that Viollet-le-Duc, as an active architect, is primarily concerned to justify the methods he has put into practice, whereas Ruskin, even more than a theorist, is above all a stylist and connoisseur who has little experience in the practice of building itself. For Nikolaus Pevsner, the main difference between the two authors comes down to one of ‘sensibility’, with all the vagueness and subjectivity implied by such a term: in Viollet-le-Duc, Pevsner sees a French rationalism that favours the concrete and empirical, and in Ruskin, he sees a supposedly English emotivity that privileges suggestion and evocation.[19] Spurr specifies that for Viollet-le-Duc:

Architectural restoration was a new science, like those of comparative anatomy, philology, ethnology, and archaeology. Laurent Baridon has shown how the architect’s ideas incorporate the scientific concept of organicism, characteristic of the mid-nineteenth century: the architectural restorer is to the medieval building what the paleontologist is to the remains of a prehistoric animal: each of them seeks to reconstitute an organism …The point, however, was not merely to re-create a building by imitating medieval practices but rather to find the solutions to architectural problems that medieval artisans would have adopted had they had the technical means available to the nineteenth century. For Viollet-le-Duc, medieval architecture is not essentially a multiple series of historical phenomena rooted in distinct and local contexts. Rather, his theory implies the existence of an ideal form of the building independent of its concrete realization at any given historical moment.[20]

Spurr summarises the essential differences between Ruskin and Viollet-le-Duc as allegory versus symbol, after the definitions provided by Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Georg Friedrich Creuzer, and Walter Benjamin. Ruskin’s preservation would be favouring an ‘allegorical conception of architecture’, whereas Viollet-le-Duc’s restoration would give life to a more symbolic view.[21] However, what Spurr’s remark primarily shows is that the French architect’s organicist conception of architecture meets Ruskin’s in their shared common love for the Gothic, which formally mimics the vegetal realm. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe was the first to use the metaphor of the tree growing towards the sky to define by analogy the majesty of Strasbourg’s cathedral, as Laurent Baridon reminds us: Gothic art summarises and schematises the metamorphoses of plants.[22]

Both Ruskin and Viollet-le-Duc formed themselves in the same regions of the French Alps, delighting in the same geography, and sharing strikingly similar views on the importance of drawing in the development of taste and intellect, as Cynthia Gamble remarks.[23] Both held Chamonix as the place they preferred on Earth, as André Hélard has documented, and both used geology as a model of what architecture should be like.[24] Ruskin immensely admired Viollet-le-Duc’s ten-volume, richly illustrated Dictionnaire raisonné de l’architecture française du XIe au XVIe siècle (Analytical Dictionary of French Architecture from the Eleventh to the Sixteenth Century) from which he often quoted. In 1884 he described it as ‘the best-informed, most intelligent, and most thoughtful of guides’, and stressed the architect’s many qualities: ‘His knowledge of architecture’, ‘his artistic enthusiasm, balanced by the acutest sagacity, and his patriotism, by the frankest candour’.[25] In a letter written on 2 March 1887, Ruskin advised his young male addressee to study Viollet-le-Duc: ‘There is only one book on architecture of any value—and that contains everything. M. Viollet-le-Duc’s Dictionary. Every architect must learn French, for all the best architecture is in France—and the French workmen are in the highest degree skilful’.[26] Nikolaus Pevsner compares the views of Ruskin and Viollet-le-Duc, and underlines that several opinions bind the two: for instance, their constant celebration of the Gothic art of the thirteenth century, and the importance that they both attach to a certain notion of ‘truth’ in architecture in which the appearance of a building should correspond to its actual structure and material composition.[27] As Travis Brock Kennedy noticed after having studied the marginalia left by Ruskin in his own copy of Viollet-le-Duc’s Dictionary, the polarity of Ruskin contra Viollet-le-Duc was in fact motivated by petty jealousy and other trivial causes. They were in fact different yet fundamentally kindred spirits, unified in their belief in the value of Gothic architecture and advocated of its preservation and enduring relevance in a rapidly changing world.[28] Like Ruskin, Viollet-le-Duc never tires of explaining, analysing, reasoning, demonstrating. Both are natural pedagogues, polymaths who hold a fascination for botany, for geology, for geometry (see the fourth volume of Modern Painters), the formation of crystals (The Ethics of The Dust), for mountains in general and Chamonix and Mont Blanc in particular. Just like Ruskin, Viollet-le-Duc seems fearless; like Ruskin, he admits as his guide ‘absolute reverence for the Truth’.[29] Both men dissect Gothic art, Viollet-le-Duc to deduce that the grandeur of Gothic rests on mastery of structure, whereas Ruskin prefers to think that the essence of Gothic rests in the surge of emotion it provokes. However, aren’t these two interpretations cause and effect, that is, the two sides of the same coin? Otero-Pailos’s latex casts manage to materialise the specific interface between structure and emotion that seemed to be common to the preoccupations of the two authors. When confronted with the gigantic matrix of soft material lit from behind, the spectator is able to feel the interdependence between emotion, structure, time and space.

In Otero-Pailos’s work, the pollution trace is constituted of the very material (dust particles) that adds to the value of the wall according to Ruskin, while it shows in plain sight what this very wall actually was several centuries before. This is made strikingly observable when Otero-Pailos juxtaposes latex and wall; the vertiginous divide of the centuries then becomes literally and dramatically detectable with the eye. The isomorphic print would also have a place in the conceptual museum imagined by Boito, who saw in each monument its own embedded meta-museum. For instance, he advocated that each palazzo should contain all of the original fragments of their walls that had to be replaced; this is why nowadays many palazzi still contain their own fragments, according to his recommendation.[30]

The Ethics of Dust series thus admirably preserves not only the building that was dear to Boito, but also the very layer that Otero-Pailos is able to take off, which paradoxically corresponds to Ruskin’s beloved time stains. The angle chosen by Otero-Pailos to qualify his work belongs to a territory usually claimed both by the world of architecture conservation and that of art. Otero-Pailos states that he wants to influence the perception we have of our environment, whether it be through Venetian walls and art history, through plasticity, or through literature:

Preservation is not just working on monuments but also include these kinds of performance pieces, ceremonies if you will, that happen during the process of visiting historic sites. Preservation organizes how one visits. In fact, I define preservation as the organization of attention. It’s the kind of organization of attention that is all about distracting. It’s distracting you from looking at that which you are not supposed to be looking at. For instance, think about the coast here as and the whole branding of Croatia as ‘the Mediterranean as it used to be.’ It’s interesting that it is diverting you from Croatia as it used to be. The whole organization of your attention is towards the Mediterranean, and that’s the whole journey and the whole experience that you’re supposed to have.[31]

The question then becomes: what experience does Otero-Pailos’s work provoke in the viewer? One can see that everything, from discourse to representation, aims at framing: framing nature (whose definition itself is entangled in human perception and conception), framing the place of the human in nature, framing space and time as envisioned by humans. The environment is, after all, always perceived, and therefore always selected, analysed, and envisioned in the way an artefact would be.

I contend that not only does Otero-Pailos’s work make this evident, but that the above is precisely what Ruskin himself wanted to demonstrate throughout the thousands of pages of Modern Painters, which he wrote for seventeen years so as to understand better the very nature of the act of perceiving and its functioning.[32] Otero-Pailos has managed to turn dust into a noble material again, long after Man Ray and Marcel Duchamp deemed it plastically interesting (albeit not noble) in their Elevage de Poussière (Dust Breeding) in 1920, and before Arte Povera, Minimal Art, and Land Art in their turn used some of its unexpected properties to signify our own insignificance, and the possible ecological catastrophe to come.[33]

From the monumental to the intimate

In The Stones of Venice, Ruskin celebrates the damaged beauty of Venetian walls, likening them to translucent masses of rich, golden-brown seaweed:

The floor of it is of rich mosaic, encompassed by a low seat of red marble, and its walls are of alabaster, but worn and shattered, and darkly stained with age, almost a ruin,—in places the slabs of marble have fallen away altogether, and the rugged brickwork is seen through the rents, but all beautiful; the ravaging fissures fretting their way among the islands and channelled zones of the alabaster, and the time-stains on its translucent masses darkened into fields of rich golden brown, like the colour of seaweed when the sun strikes on it through deep sea. … Venice has made her choice.[34]

Venice has become the new Atlantis, and the surface world imperceptibly becomes the underwater world. Venice has made her choice, that of sinking deeper and deeper, offering us a glimpse of worlds mere mortals are not even able to fathom. Venice has become sublime, in the Burkean sense: sublime because of the natural supplements that signal the ruin, and that reside in ruptures, fissures, and the picturesque stains and moss. The architectural surface thus materialises the effects of nature and of time, and this is what constitutes the sublime. Otero-Pailos’s work has indeed literally materialised the sheer quality of the splendid walls described above, compared to an organic mass of algae-like texture. According to where the spectator happens to stand, the sheet is either matt and opaque (dust appears then in a three-dimensional pattern) or, on the contrary, it becomes translucent and golden, revealing the uneven surface sculpted by dust. The traditional opposition between recto and verso, between obverse and reverse side then ceases to be pertinent, both sides uniting to give a complex, multifaceted, plastic artefact. I am afraid that photographs cannot do justice to the works, forbidding us to experience the skin-like transparency of the latex sheet.[35] This soft latex wall can be hung, but it can also be rolled to be transported from museum to mausoleum, to use Robert Smithson’s provocative phrase.[36] It is a wall which has become an anti-wall, fragile, soft, as delicate as it is resistant; it is a wall which has been reduced to its own dirty surface, a wall which has become essentially plastic, making a Ruskinian dream of sensuality come true. The paradox is indeed a challenge: how can a wall become sensuous? How can such a gigantic artefact be turned into a moving work that evokes delicate intimacy? It seems extraordinary that a mere wall can become sensual. Laurent Baridon remarks in his study of Viollet-le-Duc that at Pierrefonds, the white polished stonewalls there give the startling impression that they form a second skin which perfectly clings to the structure of the castle: ‘fashioned like dough would appear to the sight, the stone expresses itself in the rational language of the structure, but also adopts the language of plasticity. It links contiguous spaces through volumes both clear and supple’.[37] The work of Otero-Pailos indeed has realised the feat of giving the wall a skin-like consistency. The secret of such unexpected sensuality lies in the material chosen here, which is truly like human skin: thin, soft, still feeling almost moist to the touch once it has dried, latex mimics live tissue to the touch and sight. The contrast between the wall that we think we see and the actual flaccidity of the sheet of latex is maximal, and I confess that the first time I encountered the Ducal Palace veil in the Arsenal of the Biennale I confused this wall with the real wall of stone, overlooking it completely, only a minuscule label caught my attention, mentioning The Ethics of Dust. I was intrigued, thought it was a mistake made by the staff as there was ‘nothing to see’ (such a cliché of contemporary art indeed, although this was by no means a readymade), but I came back, minutely inspected the wall, and then I understood that some unknown artefact of the strangest kind stood before my bewildered eyes. Otero-Pailos’s walls are monumental in size, but they paradoxically summon in the spectator an experience which is most intimate, as the latex looks and feels like human skin, an organ that separates us from and connects us to the outside world. A latex skin so soft, so thin, so evocative of intimacy that it bears an almost erotic quality (the sexual connotations of latex are widely known).[38] Latex has a mammalian quality; it is the material which is closest to an organic membrane. We then face an ‘objet inframince’ to use Duchamp’s terminology.[39] The ‘infra-thin’ [inframince] object is an object which belongs to and questions several possible categories in a provocative, tricky and almost imperceptible way, in the way for example that the readymade questions the difference between an industrially-produced everyday object and a museum artefact. Duchamp was the first artist to make sculptures with soft objects and to conceptualise the importance of the most tenuous, insubstantial forms. The first soft sculpture he called Trois stoppages étalon (Three Standard Stoppages, 1913–14), to be followed by the first ever soft readymades, Pliant… de voyage (Traveller’s Folding Item, 1916) and Sculpture de voyage(Sculpture for Travelling, 1918), composed of swimming caps held by threads. As their titles underline, the most remarkable common quality of these artworks at the time is their lightness, plasticity, and portability: with Duchamp, sculpture truly becomes portable. Sculpture for Travelling did not exist for more than four years, as the latex quickly deteriorated before completely vanishing into dust.[40]

I think that The Ethics of Dust can be envisaged as a vanitas that refers to our own skin, our own bodily envelope: if it moves us with its extraordinary tactile quality, it is because it resembles us. The ‘infra-thin’ object bridges differences in colour, texture, softness, before visually becoming exactly like skin. Robert Lebel wrote that ‘Duchamp’s obsession … was the distance and the difference between beings; these were to him both necessary and intolerable at the same time’.[41] Intolerable because almost imperceptible, and often made possible by technological breakthrough.[42] This latex wall becomes a skin wall when you take long enough to experience all of its physicality. Just like this wall, human skin is the organ which separates inside from outside, the living interface between us and the world; this wall of latex also exists as an interface between space and time, as the most beautiful homage that can be paid to Venice. Ruskin’s time stains have come to live a life of their own, and the spectator can touch the traces of time and feel centuries rolling under the tips of their fingers.[43] Otero-Pailos’s formidable soft wall reminds us of our existence in time. As I possibly imagine myself contained in the dust that clings on the wall—dust to dust, ashes to ashes—I can also mentally grasp the nature and scale of the real wall. ‘The same, but not the same’, to quote Thomas Hardy.[44] This work of art therefore questions the very nature of representation.

Producing and reproducing the Stones of Venice

The Ethics of Dust thus enact a new status for the work of art. From world object (a wall of the Ducal Palace) to pollution layer to be eradicated, it mutates into a museum artefact (according to Boito) before also challenging science after being captured by Otero-Pailos’s cutting-edge technology. This print, in a way, questions the semiotic status usually granted to the capture of traces on a surface; here, the artefact does not simply represent the dust, it is the dust itself. According to philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce’s categories, the print of dust is thus a double index: it is the index of an index, or, if we prefer, the print of a print.[45] Otero-Pailos’s sheet is indeed a double print—the print of dust on latex captured after the print of dust on a stone wall—but it is also at the same time, and most exceptionally, an icon in the Peircean sense. One would perhaps be tempted to say that this work represents a wall, as a mimetic painting would do, but it wouldn’t be accurate, since this wall doesn’t represent: it is. The dust doesn’t represent dust, it is the dust of the Ducal Palace left by centuries of pollution. And thus, it becomes part of a very special category of images: it belongs to the ultra-private set of contact icons formed by the Turin shroud or by Veronica’s veil, the only difference being that Otero-Pailos’s is manmade. The artefact is thus a vera icon, a perfectly mimetic representation of which there exists only one copy in the world, whose exact equivalent will never be able to be produced ever again: the scientific name of this image is a conigraph.[46] The Ethics of Dust is thus a Venice veil, a Vera Veneziana, a real fragment of space and time which is displaced, and which by synecdoche phantomically evokes the city which we often reduce to the spectral beauty of its decaying facades. In the final analysis, The Ethics of Dust is to be conceived as the mask of a mask, a plastic mise en abyme of a splendid apparition, ceaselessly and infinitely reproduced by artists, or mere tourists in a variety of visual media ranging from painting to video art via photography. The Ethics of Dust is thus the ultimate literal (real), one-of-a-kind print of the metaphorical impression that Venice never fails to produce on the spectator, an impressive enactment of the task that Ruskin strove to perform during his life: ‘I should like to draw all of St Mark’s … stone by stone, to eat it all up in my mind—touch by touch’.[47]

To think of the world in terms of interactions between whole and fragments, to conceive the whole through the minutest part, was the arduous task that Ruskin challenged himself to perform all his life:

Not only is there a partial and variable mystery thus caused by clouds and vapours throughout great spaces of landscape; there is a continual mystery caused throughout all spaces, caused by the absolute infinity of things. WE NEVER SEE ANYTHING CLEARLY. … everything we look at, be it large or small, near or distant, has an equal quantity of mystery in it; and the only question is, not how much mystery there is, but at what part of the object mystification begins. We suppose we see the ground under our feet clearly, but if we try to number its grains of dust, we shall find that it is as full of confusion and doubtful form, as anything else; so that there is literally no point of clear sight, and there never can be. What we call seeing a thing clearly, is only seeing enough of it to make out what it is; this point of intelligibility varying in distance for different magnitudes and kinds of things, while the appointed quantity of mystery remains nearly the same for all.[48]

Visible and intelligible constantly mingle in our perception of the world; it seems that Jorge Otero-Pailos’s work successfully reaches perfect balance between the two, enacting powerful synergy. The Ethics of Dust makes us feel like touching with our skin the century-old layer of dust on the soft and enticing surface of latex, and suddenly one understands that depth lies in every surface, even in the dust we curse every day in our mundane domestic existence. We normally see the dust, but we rarely experience it; Otero-Pailos’s work thus realises one of the greatest feats famously recorded by Ruskin when he wrote that ‘The greatest thing a human soul ever does in this world is to seesomething and tell what it saw in a plain way. Hundreds of people can talk for one who can think, but thousands can think for one who can see. To see clearly is poetry, prophecy and religion, all in one’.[49] Through his unique artefact, Jorge Otero-Pailos gives the world a chance to glimpse at a vanishing poetical world, while enabling his spectators to think and to see at the same time.

Citations

[1] Jorge Otero-Pailos, quoted in Laura Raskin, ‘Jorge Ortero-Pailos and the Ethics of Preservation’, Places Journal, January 2011, accessed 26 January 2021, https://placesjournal.org/article/jorge-otero-pailos-and-the-ethics-of-preservation/?cn-reloaded=1.

[2] Ruskin, 18 (The Ethics of The Dust: Ten Lectures to Little Housewives on the Elements of Crystallization, 1866).

[3] Ruskin, 8.234 (The Seven Lamps of Architecture, 1849).

[4] Ruskin, 8.108.

[5] Ruskin, 8.109.

[6] William Morris and Phillip Webb, The Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings Manifesto, written in March 1877 and published in ‘Restoration’, The Atheneum 2591 (23 June 1877), p. 807.

[7] See the introduction by Eva Ebersberger and Daniela Zyman (eds.), Jorge Otero-Pailos: The Ethics of Dust (Cologne and Vienna: Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary, 2009), p. 21.

[8] Ruskin, 34.31–40 (The Storm-Cloud of the Nineteenth Century, 1884). See also Michael Wheeler, Ruskin and Environment: The Storm-Cloud of the Nineteenth Century (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1995). On the status of the decried pollution, and the exact correspondence of moral reformation and ecological concern, see Brian J. Day, ‘The Moral intuition of Ruskin’s “Storm-Cloud”’, Studies in English Literature 1500–1900 45:4 (2005): pp. 917–33.

[9] Courtney Skipton Long, ‘Dust to Dust: Jorge Otero-Pailos after John Ruskin’, in Tim Barringer, Tara Contractor, Victoria Hepburn, Judith Stapleton, and Courtney Skipton Long (eds.), Unto This Last: Two Hundred Years of John Ruskin (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019), p. 88.

[10] Ruskin, 9.38 (The Stones of Venice 1, 1851): ‘The Ducal palace of Venice contains the three elements in exactly equal proportions—the Roman, Lombard, and Arab. It is the central building of the world’.

[11] Ruskin, 8.244 (The Seven Lamps of Architecture, 1849).

[12] Mark Wigley, interviewed by Francesca Von Habsburg, in Ebersberger and Zyman (eds.), The Ethics of Dust, p. 15. Mark Wigley is a New-Zealand-born architect specialising in planning and preservation, and he teaches at the University of Columbia, New York.

[13] Lucretius, De Rerum Natura [first century BC] (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 2007). For a more detailed analysis, see Ella Mershon, ‘Ruskin’s Dust’, Victorian Studies, 58:3 (2016): pp. 464–92.

[14] Aloïs Riegl, Der moderne Denkmalkultus, seine Wesen und seine Entstehung (Vienna: W. Braumüller Verlag, 1903). For an English translation see Kurt W. Forster and Diane Ghirardo, ‘The Modern Cult of Monuments: Its Character and Its Origins’, Oppositions 25 (1982): pp. 21–51.

[15] Ruskin, 8.234 (The Seven Lamps of Architecture, 1849).

[16] On the recently discovered daguerreotypes of Ruskin, see Ken and Jenny Jacobson, Carrying Off the Palaces: John Ruskin’s Lost Daguerreotypes (London: Bernard Quaritch, 2015).

[17] Camillo Boito, Conserver ou restaurer, les dilemmes du patrimoine [1893], (trans.) Jean-Marc Mandosio (Paris: Tranches de villes, 2000). On this subject, also see David Spurr, Architecture and Modern Literature (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2012) p. 142; Alain Gigandet, Lucrèce: Atomes, Mouvement, physique et éthique (Paris: PUF, 2001); Pierre Grimal, Lucrèce, De la nature, l’hymne à l’univers (Paris: Ellipses, 1990); Duncan F. Kennedy, Rethinking Reality, Lucretius and the Textualisation of Nature (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 2002). See Ebersberger and Zyman (eds.), The Ethics of Dust, p. 21.

[18] Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, Dictionnaire raisonné de l’architecture française du XIe au XVIe siècle (Paris: Édition Bance-Morel, 1854–68). My translation.

[19] Nikolaus Pevsner, ‘Ruskin and Viollet-le-Duc’, in Geert Bekaert (ed.), A la Recherche de Viollet-le-Duc (Bruxelles: Mardaga, 1980) p. 149.

[20] Spurr, Architecture and Modern Literature, p. 148–9.

[21] Spurr, Architecture and Modern Literature, p. 146.

[22] Laurent Baridon, L’imaginaire scientifique de Viollet-le-Duc (Paris: L’Harmattan, 1996), pp. 159, 209.

[23] See Cynthia Gamble, ‘John Ruskin, Viollet-le-Duc and The Alps’, The Alpine Journal (1999): pp. 185–96.

[24] See André Hélard, John Ruskin et les Cathérales de la Terre (Chamonix: Guérin, 2005), and André Hélard, ‘Ruskin and the Chamonix Chronotope’, in Keith Hanley and Emma Sdegno (eds.), Ruskin, Venice and Nineteenth-Century Cultural Travel (Venice: Libreria Editrice Cafoscarina, 2010).

[25] Ruskin, 33.465 (The Pleasures of England, 1884).

[26] Quoted in Michael W. Brooks, John Ruskin and Victorian Architecture (London: Thames and Hudson, 1989), p. 290.

[27] Nikolaus Pevsner, Ruskin and Viollet-le-Duc (London: Thames and Hudson, 1970). See also Spurr, Architecture and Modern Literature, p. 147: ‘In The Seven Lamps, for example, Ruskin tells us that the architect must avoid the suggestion of a means of structural support other than the real one, as well as the painting of surfaces to represent a material other than that of which they are made. Likewise, Viollet-le-Duc insists in the Entretiens that “stone appear really as stone, iron as iron, wood as wood,” and so on. (1:472). Both writers seem to agree on the role of the people in constructing Gothic architecture. For Viollet-le-Duc, it is to the common people of the thirteenth century that we owe the great monuments of that age, while for Ruskin these buildings represent the work of an entire race (Pevsner 18). In his last major work, The Bible of Amiens (1880–5), Ruskin several times cites Viollet-le-Duc as an authority on French medieval architecture’.

[28] Travis Brock Kennedy, ‘HERE THE GREAT FLAW IN THE MAN! A Prolegomena to Ruskin’s Marginalia in Viollet-le-Duc’s Dictionnaire raisonné de l’architecture française du XIe au XVIe siècle for Contemporary Historic Preservation’ (Master’s diss., Columbia University in the City of New York, 2018).

[29] John Summerson, ‘Viollet-le-Duc et le point de vue rationnel’ [1947] in Bekaert (ed.), A la Recherche de Viollet-le-Duc, p. 113.

[30] In this fashion, the Museo Dell’Opera, situated at sea level in the Ducal Palace, contains, for instance, thirteen Gothic capitals that were replaced from 1876 to 1887.

[31] Jorge Otero-Pailos, quoted in Ebersberger and Zyman (eds.), The Ethics of Dust, p. 17.

[32] On this subject, see Fabienne Gaspari, Lawrence Gasquet, and Laurence Constanty-Roussillon, Ruskin sur Turner: l’éblouissement de la peinture (Pau: Presses Universitaires de Pau et des Pays de l’Adour, 2006).

[33] See also François Dagognet, Catherine Elkar, and Emmanual Latreille, Poussière (Dust Memories), exhibition catalogue, Fonds Régionaux de Bourgogne et de Bretagne (Morlaix, Saint-Briac, Rennes: 1998); Georges Didi-Huberman, Génie du non-lieu, air, poussière, empreinte, hantise (Paris: Minuit, 2001); François Dagognet, Pour le moins (Paris: Encre Marine, 2009).

[34] Ruskin, 9.86 (The Stones of Venice 1, 1851).

[35] See the artist speak about his work in ‘Jorge Otero-Pailos, The Ethics of Dust’, YouTube, 2009, accessed 9 November 2020, https://youtu.be/xLkTAJIqzTs.

[36] See Robert Smithson, ‘Some Void Thoughts on Museums’, in Jack Flam (ed.), Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings [1979], second edition, (Berkeley and Los Angeles: The University of California Press, 1996).

[37] Baridon, L’Imaginaire scientifique de Viollet-le-Duc, p. 216. My translation.

[38] ‘The veil of latex that [Otero-Pailos] interposes between us and reality has a retardant effect, in so far as it postpones, or maybe, prolongs in the observer the spasm before a full and satisfying aesthetic orgasm. And I don’t speak of orgasm now without a precise reason, since the most common and widespread latex object in the world is certainly the condom, which in Italian is called—strangely enough—“preservativo (preservative)”’. Lorenzo Fusi, ‘Ethics impressed on Dust: Nihil potest homo intelligere sine phantasmate’, in Ebersberger and Zyman (eds.), The Ethics of Dust, p. 74; ‘Given the material and its slight but noticeable odour, you might think it’s rubber-fetish day at Westminster (and it probably is, for some member or other). Cloth squares and rectangles are embedded in the yellowish, off-white latex, giving it a patched, uneven look. There are occasional smears of dirt, dark dribbles that look like old, coagulated blood, and lighter patches reminiscent of surgical dressings. Suppuration comes to mind. Wounds. Healing. Evidence. I cannot look at Jorge Otero-Pailos’s The Ethics of Dust without the associations tumbling in, seeing what isn’t there. Or rather seeing what is there, in the captured tide-lines and whorls of commonplace muck, but seeing something more, like the images one sees in the fire or an accidental smudge of paint, finding a pattern where none exists’. Adrian Searle, ‘The Ethics of Dust: A Latex Requiem for a Dying Westminster’, The Guardian, 29 June 2016, accessed 10 August 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/jun/29/the-ethics-of-dust-jorge-otero-pailos-westminster-hall-artangel.

[39] See on this subject Thierry Davila, De l’inframince: Brève histoire de l’imperceptible, de Marcel Duchamp à nos jours (Paris: Editions du Regard, 2010).

[40] For more details, see Maurice Fréchuret, Le Mou et ses Formes (Paris: Ecole Supérieure Nationale des Beaux-Arts, 1993), p. 45.

[41] Robert Lebel, Marcel Duchamp (Paris: Trianon, 1959), p. 61. My translation.

[42] On this subject, see Georges Didi-Huberman, L’Empreinte (Paris: Editions du Centre Pompidou, 1997), p. 166.

[43] For some interesting developments on the possible signification of the wall for Ruskin, see Anuradha Chatterjee, John Ruskin and the Fabric of Architecture (London: Routledge, 2018). Chatterjee claims that Ruskin advocated a theory of architecture as surface, founded on the analogy between building and the well-dressed female figure.

[44] Thomas Hardy, Tess of the d’Urbervilles [1891] (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1993), unpaginated, Kindle edition.

[45] See Charles Sanders Peirce, ‘Logic as Semiotics: The Theory of Signs’, in Justus Buchler (ed.), Philosophic Writings of Peirce (New York: Dover, 1955), p. 108. Peirce treated sign theory as central to his work on logic, as the medium for inquiry and the process of scientific discovery. The complexity of his sign classifications (semiotic triangle) make him one of the most essential contributors to semiotics. In his theory, all representations necessarily fall into three possible categories of signs, namely Icons, Indexes, and Symbols. Although Peirce’s precise thoughts about the nature of this division were to change at various points in his development of sign theory, the division nonetheless remains throughout his work, and constitutes a useful tool to address the complexity of representation. For more on that subject, see T. L. Short, Peirce’s Theory of Signs (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), and Jean-Pierre Cometti, Jacques Morizot and Roger Pouivet, Questions d’esthétique (Paris: PUF, 2000), pp. 64–7.

[46] I borrow this term from Valeria Burgio (from ancient Greek konis, dust, and graphein, to write), ‘The Vera Icon of Venice’, in Ebersberger and Zyman (eds.), The Ethics of Dust, p. 42.

[47] ‘There is the strong instinct in me which I cannot analyse to draw and describe the thing I love―not for reputation, nor for the good of others, nor for my own advantage, but a sort of instinct like that for eating or drinking. I should like to draw all St Mark’s and all this Verona stone by stone, to eat it all up into my mind, touch by touch’. Ruskin to his father John James Ruskin, Verona, 2 June 1852, quoted in Ruskin, 10.xxvi.

[48] Ruskin, 4.76 (Modern Painters 4, 1856).

[49] Ruskin, 4.333 (Modern Painters 3, 1856).