Imitating a Model, Establishing an Identity: Copying San Juan de los Reyes at San Andrés, Toledo[1]

In 1957 the eminent art historian José María de Azcárate published an article dedicated to the master mason Antón Egas (doc. 1475–ca. 1531). Azcárate’s reconstruction of Antón Egas’s life and works briefly considers the Epiphany Chapel in the presbytery of San Andrés, a parish church in Toledo (Fig. 8.1), and the Franciscan convent of Santa María de Jesús in Torrijos, destroyed in the nineteenth century.[2] While both buildings are scarcely documented, Azcárate attributes them to Antón Egas on the basis of their visible or documented similarity to San Juan de los Reyes (Fig. 8.2), the Toledan convent established by the Spanish monarchs Isabella and Ferdinand shortly after the battle of Toro (1476), a decisive event in the War of Succession that eventually confirmed Isabella’s accession to the throne of Castile.[3]

Initially overseen by the administrator (mayordomo) Mendo de Jahén, the master mason Juan Guas, and his long-time collaborator Egas Cueman, the construction of the convent—especially the cloisters and the church’s east end and crossing dome—was completed by Cueman’s sons Enrique and Antón Egas after Guas’s death in 1496.[4] Built by some of the leading architects of the late fifteenth century, and conceived in thanks for the victory at Toro, San Juan de los Reyes was charged with great political and religious significance from its inception. It was dedicated to Isabella’s patron saint, John the Evangelist, and inhabited by the Observant Franciscan order, which played a role in the Catholic Monarchs’ attempts to achieve religious reform.[5] San Juan de los Reyes was also initially conceived as a pantheon for the royal couple, a function transferred to the Capilla Real in Granada after the conquest of the city in 1492.[6] During the war that preceded this conquest, the Monarchs decorated the exterior of the convent with the chains of liberated Christian prisoners, turning it into a monument to their military success.[7] As David Nogales has recently suggested, the celebration and memorialisation of the convent’s royal founders was further articulated in the conventual library, richly endowed with panegyrics and other political and historical texts favourable to the royal couple.[8]

Given the list of outstanding craftsmen employed in the construction of San Juan de los Reyes and the strength of the Catholic Monarchs’ personal involvement in its establishment and endowment, it is perhaps not surprising that the convent, and its church in particular, should have served as architectural model for other sites. In their evident imitation of San Juan de los Reyes, Santa María de Jesús and the Epiphany Chapel can thus be considered as particularly remarkable examples of a wider phenomenon, one which has so far received only scant scholarly attention.[9] Azcárate only mentioned it in passing and focused exclusively on questions of authorship. For him, architectural similarities among the three sites resulted from the close personal relationship between Antón Egas and Juan Guas, which encouraged the repetition of successful models established by the older artist.[10] However, due to the absence of documentary evidence, neither Santa María de Jesús nor the Epiphany Chapel can firmly be attributed to either architect. Attempting to circumvent this absence and deepen our understanding of the phenomenon, this essay will explore architectural imitation from the perspective of patronage.

Information on the design and construction of Santa María de Jesús and the Epiphany Chapel may be limited, but both buildings were commissioned by eminent figures at the royal court whose biography and aspirations are relatively well documented. Destroyed in the nineteenth century, Santa María de Jesús offers limited possibilities of analysis. Introducing it as a revealing comparison, I will here focus instead on the Epiphany Chapel in order to sketch a portrait of the social and personal circumstances which may have led an early sixteenth-century patron to commission a building modelled on San Juan de los Reyes. As I will argue, the design of the chapel draws on that of the convent because the latter contained a flexible range of ideologically charged design elements which could be adapted to promote the personal achievements and dynastic aspirations of the chapel’s patron Francisco de Rojas, while mediating between his individual decisions and the conflicting interests of his family.

Wonderful Emulation: Santa María de Jesús

Little survives of Santa María de Jesús, the richly endowed convent established in 1492 by Gutierre Cárdenas and Teresa Enríquez.[11] The foundation nevertheless offers an ideal starting point for my discussion, as its connection with San Juan de los Reyes was explicitly acknowledged in a history of the Franciscan order written in 1587 by Francesco Gonzaga, General Minister of the Observant Friars. Discussing the piety of the convent’s patrons and the expense of its construction, Gonzaga exclaims:

What could then be more wonderful [than this convent], which is not surpassed in any way by any other Franciscan house, not even San Juan de los Reyes in Toledo, according to which model, not to say emulation, it was built?[12]

While Francesco Gonzaga does not explicitly attribute the decision to copy San Juan de los Reyes to Santa María de Jesús’s patrons, his discussion of the site is entirely focused on their praiseworthy munificence, desire to be buried within the convent, and furnishings which they commissioned for the foundation, suggesting that he interpreted the architectural imitation of San Juan de los Reyes in terms of patrons and their choices.

Indeed, a brief summary of these patrons’ biographies reveals persuasive reasons for copying the Toledan convent. Always a loyal supporter of Isabella, Gutierre was a central figure at court, holding the offices of chief treasurer (contador mayor), commander-in-chief (comendador mayor) of the military order of Santiago for the province of León, and distinguishing himself for his courage during the war against Granada.[13] His wife, Teresa Enríquez, became one of Isabella’s closest ladies-in-waiting.[14] Teresa was known for her great devotion, earning the nickname ‘mad for the Sacrament’ (loca del Sacramento) from Pope Julius II on account of her devotion to the Host.[15] Following the death of her husband in 1503, she ensured the completion of the convent and fulfilled her husband’s dying wishes, including the commission of rich sepulchres which survived the destruction of Santa María de Jesús and are now located in Torrijos’ collegiate church. As requested by Gutierre’s will, the sepulchres are carved in marble, and his recumbent effigy is decorated with the Cross of Santiago.[16]

Studying the Epiphany Chapel in San Andrés through the lens of patronage will reveal several commonalities with Santa María de Jesús, namely a personal link to the Catholic Monarchs and the papacy; a personal experience of warfare; and a connection to Santiago and the other military orders. These similarities help to explain why two apparently contrasting buildings—one a ‘rural’ convent, the other the principal chapel of an urban parish church—both copy the same model.

Compare and Contrast: San Andrés and San Juan de Los Reyes

Seen from the square in front of its main entrance, San Andrés appears like one of many twelfth-century brick-and-rubble churches typical of Toledo (Fig. 8.3).[17] Like San Román and San Lucas, it does not have buttresses and its low nave remains covered with a wooden roof, in spite of significant seventeenth-century reconstruction.[18] In contrast, the Epiphany Chapel at the building’s east end makes a strong statement in its urban context. Although located in the presbytery of the parish church, this chapel was conceived as a private funerary space. Built in finely cut stone, it has robust buttresses and is strikingly taller than many surrounding structures (Fig. 8.4). The Epiphany Chapel was likely the fourth ashlar building to be erected in the city, preceded by the cathedral, San Juan de los Reyes, and the Hospital de Santa Cruz, the latter begun around 1503.[19] The idiosyncratic nature of working in stone in this city is expressed in the structure of the heraldic decoration and window openings on the chapel’s exterior: these elements are carved in more expensive, whiter limestone, inserted in the granite wall without structural continuity.[20] The contrast of forms and materials is particularly noteworthy on the inside, where a large pointed arch marks the rupture between the Gothic crossing and apse, and the basilican nave with its horseshoe arches (See Fig. 8.1).

With its stone structure, so unusual in its local context, the Epiphany Chapel in San Andrés echoes the striking architectural splendour of San Juan de los Reyes, which did not fail to impress visitors. For example, in 1495 the German traveller Hieronymus Münzer remarked that the convent was ‘built … newly so finely with cut and squared stone that it is a wonder.’[21] Beyond this general resonance, the Epiphany Chapel has a number of clear design similarities with San Juan de los Reyes. The east end of both churches is a shallow pentagonal apse attached to non-projecting, rectangular transepts (Fig. 8.5), although the crossing of San Juan de los Reyes is marked by a dome (Fig. 8.6) much grander than the vault of San Andrés (Fig. 8.7). Notably, San Juan de los Reyes’s plan design was also reproduced in the Capilla Real in Granada, whose construction was completed around 1517 by Enrique Egas, Antón Egas’s brother and collaborator.[22] Significantly, this ground plan differs from the trefoil-shaped design introduced in the second half of the fifteenth century by Juan Guas and associates at the monastery of El Parral, a foundation established by King Enrique IV in the late 1440s and then transformed into a private funerary chapel by the Pachecos, close allies of this king and powerful opponents of Isabella during the War of Succession.[23] As explored by Begoña Alonso Ruíz, the innovative trefoil plan of El Parral would cast an influence of its own on the design of several sixteenth-century presbyteries with a funerary destination.[24] Consideration of design and politics suggest that these two chains of architectural imitation were parallel and even competing phenomena.

In addition to significant similarities in their ground plan, the Epiphany Chapel and San Juan de los Reyes share several decorative details. While the quantity of heraldic decoration on the convent’s walls far surpasses that of San Andrés, both feature analogous inscriptions which extend along all the walls. Each inscription is designed to angle around the altarpiece, forming an architectural frame (Figs. 8.8 and 8.9).[25] The Epiphany Chapel’s altarpiece and inscription are crowned by a cross (Fig. 8.8) with rich decoration that recalls the one once decorating the entrance to San Juan de los Reyes’s cloister (Fig. 8.10).[26] In the chapel, the base of the cross features the Five Wounds of Christ and is comparable in design to the coat of arms of the Franciscan Observants carved above the doorway leading from church to cloister in San Juan de los Reyes (Fig. 8.11). The crosses and coats of arms are closely comparable in their detail, as is the foliage decorating the pilasters in both churches (Figs. 8.12 and 8.13). The altarpieces in each are flanked by empty niches (Figs. 8.14 and 8.15), perhaps intended to contain sculptures.[27] The east end of both churches originally featured three altars, still present at San Andrés and known to have existed at San Juan de los Reyes, thanks to a royal document of 1534 and a ground plan made that year for an Inquisition trial.[28]

The plan of 1534 shows a sepulchre in the centre of the crossing at San Juan de los Reyes, probably the proxy catafalque installed by Charles V in memory of his grandmother Isabella. Documents referring to its upkeep reveal that this was a semi-temporary wooden structure draped with carpets of black velvet and covered by a velvet baldachin.[29] Although the crossing of this church was never occupied by stone sepulchres, temporary structures were erected there for funerals and anniversaries. Similar possibilities existed at San Andrés, where the contract signed between the chapel’s patron Francisco de Rojas and the church’s curate on 7 January 1504 acknowledged that funerary monuments might be placed before the high altar.[30] Such sepulchres were indeed provided for in the second will of Francisco’s brother, Alonso de Escobar y Rojas, drawn up in 1531.[31] However, they were then explicitly forbidden by the regulations he introduced in 1533, and no tombs were erected there in the sixteenth century.[32] Members of the family could be buried in the crypt of the chapel and commission monuments in some of the arcosolia on the sides of the church, but the central space was reserved for temporary structures, notably the ‘coffin covered with brocade’ around which Alonso de Escobar wished his funeral and memorials to take place.[33] In both churches, the architectural structure was completed by fittings and ceremonial displays that are all but lost today.

A Complex Foundation

This short discussion of funerary practices at San Andrés has referred to the chapel’s patron, Francisco de Rojas, and his brother, Alonso de Escobar, and to one of their many changes of mind on matters of construction and design. Such wavering is typical of the Epiphany Chapel’s institutional history, partly complicated by the coexistence of long- and short-distance patronage.

Francisco de Rojas, patron of the Epiphany Chapel, served a long career as ambassador for the Catholic Monarchs. Between 1488 and 1507, he was almost uninterruptedly absent from Spain. He resided in Italy, mainly at the papal court, from 1501 to 1507 when the most important steps for the creation of the Epiphany Chapel took place.[34] Francisco’s brother Alonso de Escobar thus made decisions and carried out negotiations on site. For example, it was Alonso who signed the contract of 7 January 1504 with the church’s curate, had it confirmed by the church’s parishioners (5 January 1505), and convinced Toledo’s civic authorities to allow the chapel to extend over a nearby street (20 May 1504), a potentially complex matter in a city as built-up as Toledo.[35]

Yet, in spite of his commitments abroad, Francisco was not a passive patron. He used his privileged position at the papal court to obtain the bulls that made the chapel possible: first, the authorisation to establish a chapel, endow it with vacant benefits from Toledo Cathedral and nominate chaplains (26 December 1503); second, permission to be buried outside the convent of Calatrava la Nueva and to dispose freely of his possessions, disregarding the regulations of the Order of Calatrava, of which he was a member (21 August 1504); third, several confirmations of these rights, which had been challenged by the cathedral and the order.[36] He not only made essential contributions to the economic and liturgical endowment of the chapel, but also decisions regarding its appearance: Alonso de Escobar’s second will (1537) reveals that Francisco had returned from Rome with blocks of marble and porphyry to be transformed into the chapel’s pulpit and sepulchres.[37] Francisco’s activity increased after his return to Toledo, as he commissioned three altarpieces for the chapel from the painters Juan de Borgoña and Antonio de Comontes, and exchanged letters with the ironworker Juan Francés, who made an iron grille commissioned by Francisco for the convent of Calatrava la Nueva and probably also worked at San Andrés.[38]

Combining short- and long-distance patronage required compromise: Francisco’s initial petition to the pope and his positive reply do not seem to require that the chapel of the Epiphany be located in the presbytery of San Andrés.[39] Although Rojas may have aspired to this prime location, the idea of establishing his chapel in San Andrés’s east end may have been promoted by the curate and parishioners. This is suggested by the confirmation of 5 January 1505, which expands on the wording of the 1504 contract, to frame Francisco de Rojas’s foundation as a charitable solution to overcrowding in the church, and especially in the apse. As underlined in the confirmation, such expansion involved the purchase of houses located east of the church and was beyond the economic means of the parish alone.[40] It is perhaps such a juxtaposition of local and distant interests which resulted in the unusual difference in dedication between the church of San Andrés and its presbytery.

While Francisco’s endowment may have solved overcrowding in the parish, transforming San Andrés’s high chapel was beset with challenges of its own. The houses existing on the site were owned by another religious institution, the Colegio de Santa Catalina, and their purchase required complex negotiations and two papal authorisations which dragged on until 1512.[41] Moreover, the existing chapel was under the patronage of a Francisco Suárez, whose family initially refused to sell. The lengthy and fraught process of purchasing the site and obtaining permission to translate the corpses of Francisco Suárez’s parents, buried in the chapel, extended until 1514.[42]

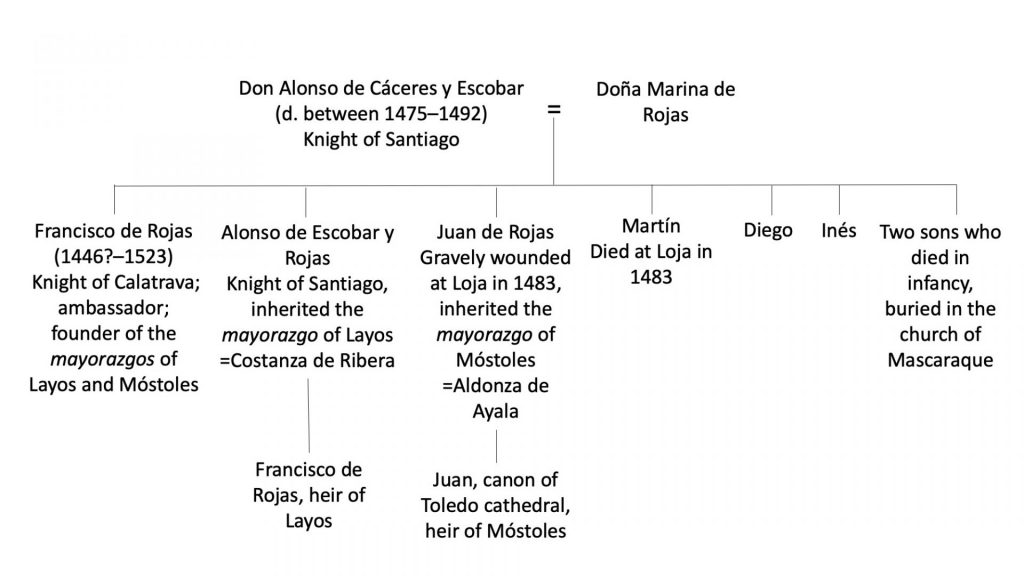

Such complex bureaucracy delayed construction, and the institutional and architectural history of the chapel is one of fits and starts, with many questions still to be answered despite Paulina López Pita’s detailed studies.[43] For example, how is it possible that, in 1513, Francisco had already commissioned the making and fitting of the Epiphany Chapel’s altarpieces when he only acquired the chapel space from the Suárez family in 1514? Questions such as this are probably unanswerable due to the loss of the documents seen by Rafael Ramírez de Arellano and Verardo García Rey in the church’s archive in the early twentieth century.[44] The wider context in which the chapel was created can nonetheless be reconstructed through the wills of Francisco de Rojas’s parents and brothers (Fig. 8.16) preserved at the Archivo Histórico Nacional in Madrid. Although not unknown to scholars, the wills have never before been used to illuminate the chapel’s architecture. While several questions remain unanswered regarding the foundation and construction of the chapel, examining these wills and Rojas’s correspondence, now in the Salazar Collection of the Real Academia de la Historia, reveals why the Epiphany Chapel is so closely modelled on San Juan de los Reyes.

Blood Ties and Bloodshed

Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo’s mid-sixteenth-century Batallas y quinquagenas portrays Francisco de Rojas as a self-made man, successful thanks to his virtue and special relationship with the Catholic Monarchs.[45] Studies have consequently emphasised Rojas’s role as the founder of a dynasty established on the entailed estate (mayorazgo) of Layos.[46] Yet the desire to establish a dynasty was already a feature of the wills of Francisco de Rojas’s parents, Alonso de Cáceres and Marina de Rojas. In 1465, they bequeathed to Francisco, their eldest child, a mejoria (a share of inheritance additional to the amount required by law), based on the revenue of their pasture land (dehesa) in Villamejor.[47] Inherited according to rules similar to those of a mayorazgo, the mejoria constituted a custom equivalent to the mayorazgo before it was officially instituted in 1505.[48] The estate was part of Marina de Rojas’s dowry, and its evident importance for the family’s economic aspirations may have determined the continuing use of the Rojas name and arms by Francisco de Rojas and his brothers.[49]

Francisco was thus emulating his parents’ actions when, in 1513, he established the two mayorazgos of Móstoles and Layos, the latter tied to the patronage of the Epiphany Chapel.[50] Neither mayorazgo was intended for Francisco’s own descendants as he did not marry. Around 1487, the Catholic Monarchs had rewarded Francisco’s first diplomatic services with the estates of Mestanza, Puertollano, Almodóvar del Campo, and Aceca, which belonged to the Order of Calatrava, an order which required its members to remain celibate.[51] He therefore always intended the mayorazgos to support the descendants of his brothers Alonso de Escobar and Juan de Rojas.[52] Francisco’s success as a diplomat close to the Monarchs had clearly translated into significant personal wealth. Such circumstances may have led his mother to reconsider the size of her son’s inheritance. After the death of her husband, sometime between 1492 and 1498, Marina de Rojas added four codicils to her will, each expressing yet another change of heart as to whether Francisco should really be favoured with the mejoria. She eventually resolved to let him enjoy it during his lifetime, as, being celibate, he could not have any legitimate heirs.[53]

Marina de Rojas’s codicils also reveal a growing preference for Alonso de Escobar. They explicitly praise Alonso as her ever-present son who helped her greatly and honestly during her old age, and single out various financial rewards to thank him for his affection.[54] Marina further indicates, implicitly, her greater respect for Alonso by referring to him as ‘commander’ (comendador), by virtue of his position in the Order of Santiago. In contrast, Francisco is not given the same title, although by the time the codicils were written he held the same status within the Order of Calatrava.[55] The same title is consistently used for their father, also a commander of the Order of Santiago, suggesting that membership of this order may have been a matter of family identity for the Rojas. This is underscored by a codicil added in 1475 to Alonso de Cáceres’s will. In this note he requested that the golden scallop shell of his uniform should no longer go to his daughter Inés, as he had previously wished, but to his son Alonso, since, like his father, he had become a knight and commander of the order. Alonso should additionally inherit his father’s copy of the order’s regulations and other documents, which would enable him to learn how to be a good knight.[56] The tradition would continue in later generations, as most of Francisco’s recorded descendants—from Antonio de Rojas in the late sixteenth century to Joseph de Rojas Pantoja in the seventeenth—are connected to the Order of Santiago.[57]

Alonso de Cáceres’s will made other significant testamentary donations to his children. Alonso de Escobar would also receive some of his father’s military equipment, namely a steel crossbow, a cuirass, leg armour and helmet. Similar gifts of military character were made to four of his six male sons, not all of whom would reach maturity. For example, Diego received his father’s tent and various weapons, including another crossbow. Some sons also received specific books. Pedro was left a sword, a crossbow, a cuirass, a copy of Boethius’s De consolatione, a book on household management and one on agriculture. Only Juan and Francisco de Rojas did not receive specific arms. With respect to books, the latter was left a richly bound Latin breviary, perhaps in acknowledgement of the studies at which he excelled in his youth.[58] In spite of its rich binding, Francisco’s Latin breviary seems somewhat impersonal when compared to the more specific donations made to his brothers. Alonso de Cáceres does not seem to have taken into account that Francisco was also training to be a knight: he left for his first military campaign in 1475, the same year that Alonso composed his will.[59] Perhaps the choice of donations suggests the dissatisfaction of Alonso de Cáceres and Marina de Rojas with a career which had not begun as they had hoped. While this can only be speculation, what is certain from the list of gifts is that the first generation of the Rojas family had a strong military ethos which conditioned the aspirations and occupations of all members of the family. Indeed, when writing to King Ferdinand around 1513 to ask for benefices, an old and ill Francisco reminded the sovereign not only of his own diplomatic activity, but also of the whole family’s participation in the War of Granada, and in particular of their role in the conquest of Loja, where his brother Juan was gravely wounded and his brother Martín killed and cut into pieces by the enemy.[60]

Collectively, this summary of Francisco’s biography and of the expectations his parents placed on him reveals several contradictions: the founder of a dynasty who could not marry; a successful son favoured by the Catholic Monarchs but perhaps not by his own parents; a knight who inherited books rather than arms. Constructing the family chapel on the model of San Juan de los Reyes—a building which he could have seen almost completed while in Castile between 1497 and 1501—Francisco could express and mediate these contradictions.

Copying San Juan de Los Reyes

Most explicitly, choosing San Juan de los Reyes as a model enabled Francisco to express his personal connection to the Catholic Monarchs, one founded on the letters of trust written by the Monarchs for their ambassador and substantiated by the intense epistolary exchange between Francisco and King Ferdinand during the former’s second stay in Rome (1501–7).[61] As noted above, San Juan de los Reyes was a royal foundation of great importance to its patrons. This personal connection was clearly articulated in the building’s rich heraldic decoration: the joint coat of arms of Aragon-Castile, created after the marriage of Isabella and Ferdinand (and never previously used by any Iberian monarch), their personal devices of the yoke and arrow (Fig. 8.17) and the joint representation of their initials on the piers of the crossing (Fig. 8.18).[62] These arms and devices referred to Ferdinand and Isabella individually, rather than through their dynasties. The two inscriptions which run around the nave and crossing of the church similarly emphasise the Catholic Monarchs’ personal achievements by referring to their matrimonial unification of Aragon and Castile and praising their personal involvement in the foundation and construction of the convent.[63]

While Ferdinand and Isabella are the only figures celebrated in the sculptural decoration and inscriptions of San Juan de los Reyes, the Epiphany Chapel functioned as a family pantheon for successive generations, and is therefore decorated with Rojas and Escobar coats of arms, and those of other families related to them by marriage (Fig. 8.19).[64] Nevertheless, the church contains a direct reference to Francisco in the form of his personal motto, ‘Light shines in the darkness, and the darkness did not comprehend it.’ Drawn from the Gospel of Saint John, the motto suggestively faces the Evangelist’s eagle and the royal coat of arms in the Isabella Breviary.

a manuscript commissioned by Francisco as a gift for Isabella while negotiating the matrimonial alliance between the children of the royal couple and those of the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I.[65] Personal achievement is strongly emphasized in the Epiphany Chapel’s inscription, which overlooks Francisco’s membership of the Order of Calatrava to underline his role as royal ambassador instead. In the space of just 116 words, this inscription contains as many as five references to the Catholic Monarchs and their territorial possessions.[66] Connections between Francisco de Rojas and the Monarchs were underscored in the Epiphany Chapel’s liturgical calendar, with anniversary masses for the souls of Isabella and Ferdinand said each year on the day of Saint John before the Latin Gate (Sancti Ioanne ad Portam Latinam), the same dedication as San Juan de los Reyes.[67]

Apart from establishing a connection with the Catholic Monarchs and thus promoting Rojas’s personal achievements, the architectural imitation of San Juan de los Reyes also acknowledged the military ethos celebrated in the wills of Francisco de Rojas’s parents. As mentioned above, the exterior of San Juan de los Reyes is decorated with the chains of Christian prisoners liberated during the war against Granada, a conflict which had a strong personal significance for Francisco and his brothers. The decoration is completed by statues of heralds, significantly restored in the nineteenth century (Fig. 8.20).[68] Heralds typically preceded and announced monarchs in their public appearances. Thus, the statues on the outside of San Juan de los Reyes immediately advertise its royal connection.[69] Moreover, heralds played a major role in grand funerary ceremonies.[70] Yet they also performed important roles on the battlefield, where they initiated battles, identified enemies, lined up troops, named the dead, recorded acts of courage and established the victor of a skirmish.[71] The chains and sculptures on the exterior of San Juan de los Reyes thus endowed it with a militaristic spirit that must have resonated with the Rojas family. While neither the chains nor the statues were replicated in the Epiphany Chapel, their existence and significance may have drawn Francisco de Rojas and Alonso de Escobar to consider San Juan de los Reyes as a model. Viewers familiar with the latter building may also have recalled those decorations when observing the chapel, located in the same city.

The absence of chains or heralds in San Andrés makes any reference to a military ethos indirect at best, however much it may have recalled San Juan de los Reyes. This may have been the result of a conscious choice to strike a compromise between Francisco’s personal membership of the Order of Calatrava and his family’s long-standing connection with that of Santiago. As suggested by a fragmentary letter of 1503, Francisco had initially planned a funerary chapel in an institution connected to both orders, the Toledan convent of Santa Fe, in the possession of the Order of Calatrava until 1494, and later owned by the Order of Santiago.[72] He later changed strategy, choosing the parish church where he had been baptised, a building with a strong connection to the history of his family but with little relation to the military orders.[73] Although Francisco Suárez, the previous patron of San Andrés’s presbytery, was a member of the Order of Santiago, Rojas’s reconstruction of the east end effectively erased the memory of Suárez and of Santiago from the church’s architecture.[74] Moreover, the newly constructed chapel remained free of sculptural or pictorial references to the Order of Calatrava. Nor did the symbols of this order feature prominently on the chapel’s movable fittings. The oldest surviving inventory of liturgical furnishings, dating to the seventeenth century, lists only one textile decorated with the Cross of Calatrava.[75] The absence of explicit references to Calatrava contrasts sharply with the decoration of another chapel connected to Francisco, the Capilla Dorada in the convent of Calatrava la Nueva. Francisco initially owned this space but sold it after choosing San Andrés as his burial site. It was acquired by the comendador mayor García de Padilla, who requested Crosses of Calatrava to be painted onto the altarpiece and stained-glass windows, and to be sculpted in various locations on the walls. Moreover, he specified, the lettering on his sepulchre had to start with a reference to his role within Calatrava.[76] Such an emphasis is partly justified by Padilla’s role as comendador mayor, more important than that of simple comendador as held by Francisco, and also by the chapel’s location within the order’s principal seat. Yet, the accumulation of references to Calatrava contrasts markedly with their absence in the Epiphany Chapel, where there is no explicit reference to any one of the military orders, and where the architectural emulation of San Juan de los Reyes may instead have created a more general evocation of the War of Granada in which several members of the Rojas family had taken part.

As suggested by this military echo, San Juan de los Reyes offered a flexible model. Its architectural design was both rich in meaning and adaptable in form. The contract of 7 January 1504 established that the Rojas funerary chapel should feature ten piers with rich bases.[77] Ten decorated piers do indeed enclose the whole structure: four in the apse, two at either side of the crossing, and two supporting the arch leading to the chapel. The same number defines the east end of San Juan de los Reyes, as is most evident in the famous late fifteenth-century drawing. of the church’s crossing.[78] The drawing eclipses the church’s nave to focus on the east end only, and its impossible perspective reveals the ten piers simultaneously.[79] It also emphasises the crossing by absurdly reducing the apse to nothing more than the size of the altar table. While these modifications offer a distorted impression of the interior of the church, the east end as built is certainly spacious and luminous, in contrast to the relatively modest nave. As discussed by Rafael Domínguez Casas, such inflated space provided a perfect stage for funerary liturgies.[80] In San Andrés’s Epiphany Chapel, the proportions of this grand funerary space were modified to suit a more modest foundation, while still offering an ideal stage for funerary celebration. Thus, the monumental crossing dome, delineated so carefully in the Prado drawing, was significantly reduced and became a simple vault in the Epiphany Chapel. Instead, the drawing’s small apse and altarpiece were increased in size, conforming to typical Spanish practice, but perhaps also in response to the different liturgical obligations of a parish church. The private, monastic and royal arena of the convent became the shared space of the parish church, where the Epiphany Chapel’s chaplains and the curate celebrated masses within the same walls, shared precious liturgical objects and collaborated in the celebration of feast days, as required by the chapel’s constitutions of 1533.[81]

This adaptation was possible because San Juan de los Reyes possessed a set of defining features which could be suited to different contexts without losing their significance. Reproducing the shape, inscription and sculptural details of San Juan de los Reyes, the Epiphany Chapel could express a personal connection to the Catholic Monarchs together with dynastic exaltation and military ethos. These features captured the achievements and aspirations of Francisco de Rojas and his relatives. Azcárate’s suggestion that the Epiphany Chapel may have been designed by Antón Egas, a master mason with an intimate knowledge of San Juan de los Reyes, is likely, but at present undocumented. Yet, architectural imitation did not depend only on the repetition of successful models on the part of the architect. By exploring the personality and aspirations of Francisco de Rojas, the present essay has argued that copying San Juan de los Reyes enabled this patron to establish and promote a carefully crafted and lasting identity for himself and his family.

Citations

[1] This essay is based on research undertaken as part of my PhD degree, supported by CHASE and the British Archaeological Association at the Courtauld Institute of Art. Unless otherwise indicated, all translations are my own.

[2] José María de Azcárate Ristori, ‘Antón Egas’, Boletín del Seminario de Estudios de Arte y Arqueología: BSAA 23 (1957): pp. 9, 12.

[3] While recognising Antón Egas as the primary author of both buildings, Azcárate noted that his brother Enrique may also have played a part in the early stages of the Epiphany Chapel’s design. See Azcárate Ristori, ‘Antón Egas’, p. 10.

[4] On the construction history of this building, see among others María Teresa Pérez Higuera, ‘En torno al proceso constructivo de San Juan de los Reyes en Toledo’, Anales de Historia del Arte 7 (1997): pp. 11–24.

[5] Joaquín Yarza Luaces, Isabel la Católica: promotora artística (León: Edilesa, 2006), p. 16; José García Oro, ‘Reforma y reformas en la familia franciscana del Renacimiento’, in María del Mar Graña Cid and Agustín Boadas Llavat (eds.), El franciscanismo en la Península Ibérica. Balance y perspectivas (Barcelona: G.B.G., 2005), pp. 235–54. For a more critical analysis of the Catholic Monarchs’ religious reforms, see Henry Kamen, Imagining Spain: Historical Myth and National Identity (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2008), p. 87.

[6] Rafael Domínguez Casas, ‘San Juan de Los Reyes: espacio funerario y aposento regio’, Boletín del Seminario de Estudios de Arte y Arqueología: BSAA 56 (1990): p. 369.

[7] Fernando del Pulgar, Crónica de los señores reyes católicos Don Fernando y Doña Isabel de Castilla y Aragón [completed 1492] (Valencia: Imprenta de Benito Monfort, 1780), p. 259; Hieronymous Münzer, ‘Itinerarium Hispanicum Hieronymi Monetarii 1494–1495’, ed. by Ludwig Pfandl, Revue hispanique 48:113 (1920): pp. 119–20.

[8] David Nogales Rincón, ‘La capilla real de Granada. Fundamentos ideológicos de una empresa artística a fines de la Edad Media’, in Diana Arauz Mercado (ed.), Pasado, presente y porvenir de las humanidades y las artes (Zacatecas: Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes, 2014), 5: p. 200.

[9] Imitations of San Juan de los Reyes are discussed more fully in my PhD thesis, ‘Juan Guas and Gothic Architecture in Late Medieval Spain: Collaborations, Networks and Geographies’, Courtauld Institute of Art, 2020.

[10] Azcárate Ristori, ‘Antón Egas’, p. 17.

[11] On the recent rediscovery of part of the convent’s foundations, see ‘Síntesis cronólogica del rescate del yacimiento’, in ‘Santa María de Jesús: “El otro San Juan de los Reyes”. Una década de lucha pertinaz’, special issue, Cañada Real 15:16 (January 2016): pp. 13–18.

[12] ‘Quid tamen mirum, cum nulli alteri Fransciscane domui, sive etiam de sancti Ioannis Regum Toletana agatur, ad cuius exemplar, ne dicā aemulationem, costructum extitit, aliqua ex parte cedatur?’ Francesco Gonzaga, De origine Seraphicae Religionis Franciscanae, eiusque progressibus, de Regularis Observantiae institutione, forma, administrationis ac legibus, admirabilique eius propagatione (Rome: Typographia Dominici Basae, 1587), part 3, p. 631.

[13] John Edwards, The Spain of the Catholic Monarchs, 1474–1520 (Oxford: Blackwell, 2000), pp. 14–15, 20–21.

[14] María del Mar Graña Cid, ‘Religión y política femenina en el Renacimiento castellano. Lecturas simbólicas de Teresa Enríquez’, in Ana Isabel Cerrada Jiménez and Josemi Lorenzo Arribas (eds.), De los símbolos al orden simbólico femenino (ss. IV–XVII) (Madrid: Asociación Cultural Al-Mudayna, 1998), p. 147.

[15] Graña Cid, ‘Religión y política femenina en el Renacimiento castellano’, p. 149.

[16] Rosa López Torrijos and Juan Nicolau Castro, ‘La familia Cárdenas, Juan de Lugano y los encargos de escultura genovesa en el siglo XVI’, Boletín del Seminario de Estudios de Arte y Arqueología: BSAA 68 (2002): pp. 173–75.

[17] Antonio Miranda Sánchez, Muros de Toledo (Toledo: Delegación en Toledo del Colegio Oficial de Arquitectos de Castilla La Mancha, 1995), p. 34.

[18] Fernando Marías, La arquitectura del Renacimiento en Toledo (1541–1631) (Toledo: Publicaciones del Instituto Provincial de Investigaciones y Estudios Toledanos, 1983), 3: p. 7.

[19] Miranda Sánchez, Muros de Toledo, p. 63; Rosario Díez del Corral Garnica, ‘La introducción del Renacimiento en Toledo. El Hospital de Santa Cruz’, Academia: Boletín de la Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando 62 (1986): p. 166.

[20] Miranda Sánchez, Muros de Toledo, p. 64.

[21] Hieronymus Münzer, Doctor Hieronymus Münzer’s Itinerary (1494 and 1495); and Discovery of Guinea, trans. and ed. James Firth (London: James Firth, 2014), p. 120. The original Latin reads: ‘Rex Ferdinandus cum sua Regina novam illam fabricam edificat ex secto et quadro lapide adeo superbe et splendide, ut mirum sit…’ Hieronymus Münzer, ‘Itinerarium Hispanicum Hieronymi Monetarii 1494–1495’, pp. 119–20.

[22] For a recent discussion of the Capilla Real in Granada in the context of other royal pantheons, especially San Juan de los Reyes, and further bibliography, see Begoña Alonso Ruiz, ‘Las capillas funerarias de los Trastámara: de la creación de la memoria a “la grandeza humillada”’, in Olga Pérez Monzón, Matilde Miquel Juan, and María Martín Gil (eds.), Retórica artística en el tardogótico castellano. La capilla fúnebre de Álvaro de Luna en contexto (Madrid: Sílex, 2018), pp. 163–70.

[23] María López Díez, Los Trastámara en Segovia: Juan Guas, maestro de obras reales (Segovia: Caja Segovia. Obra Social y Cultural, 2006), pp. 196–215.

[24] Begoña Alonso Ruiz, ‘Un modelo funerario del tardogótico castellano: las capillas treboladas’, Archivo Español de Arte 78:311 (2005): pp. 277–95.

[25] The altarpiece now in San Juan de los Reyes is not the original, destroyed in a fire in 1808. Daniel Ortiz Pradas, San Juan de los Reyes de Toledo. Historia, construcción y restauración de un monumento medieval (Madrid: La Ergástula, 2015), p. 65.

[26] The sculpture group was moved to its present location, above the modern entrance to the convent, in the mid-twentieth century. See Daniel Ortiz Pradas, ‘Herederos de Juan Guas. Arquitectos de San Juan de Los Reyes en los siglos XIX y XX’, Anales de Historia del Arte 22 (2012).

[27] No contemporary documents describe the content of these niches. The niche on the south wall of the Epiphany Chapel is now occupied by the sculpture of a female saint, but this can hardly be the original arrangement as neither the statue’s size nor the shape of its pedestal fit the space. In 1848 one of the two niches in San Juan de los Reyes also contained a ‘large sculpture carved in the round’. See Manuel de Assas, Album artístico de Toledo: colección de vistas y detalles de los principales monumentos toledanos (Madrid: Litografía de D. Bachiller, 1848), n.p. (see under ‘Hornacina lateral de la Capilla Mayor’).

[28] Filemón Arribas Arranz, ‘Noticias sobre San Juan de los Reyes’, Boletín del Seminario de Estudios de Arte y Arqueología: BSAA 29 (1963): p. 72n24, and Inquisición, 3079, no. 7 (M.P.D., 112), Archivo Histórico Nacional (hereafter AHN).

[29] Domínguez Casas, ‘San Juan de Los Reyes: espacio funerario y aposento regio’, pp. 373–34.

[30] Rafael Ramírez de Arellano, Las Parroquias de Toledo. Nuevos datos referentes a estos Templos sacados de sus archivos (Toledo: Talleres Tipográficos de Sebastián Rodríguez, 1921), p. 12.

[31] Alonso de Escobar’s will of 17 June 1531 requested the construction of a pulpit and centralised sepulchre, specifying that materials were already available (see below). Consejos, 32586, leg. 3, no. 10, fols. 242 and 242v, AHN.

[32] The regulations of 1533 confirm that relatives could be buried beneath the floor of the chapel, but without decorated tombstones (piedras de sepulturas) or statues (bultos). IV/1863, s.f., Archivo Diocesano de Toledo (hereafter ADT). However, in 1791 the chapel’s patron ordered that a tomb be moved away from the centre of the space. See Paulina López Pita, Layos: origen y desarrollo de un señorío nobiliario, el de los Rojas, condes de Mora (Toledo: Caja de Ahorros, 1988), p. 114.

[33] ‘solamente se ponga un ataud con el pano de brocado en la capilla…’ ‘Testamento que hiço Alonso de Escobar’ (17 de junio de 1531), Consejos, 32586, leg. 3, no. 10, fol. 239r, AHN.

[34] For Rojas’s activity in Rome, see Álvaro Fernández de Córdova Miralles, ‘Diplomáticos y letrados en Roma al servicio de los Reyes Católicos: Francesco Vitale di Noya, Juan Ruiz de Medina y Francisco de Rojas’, Dicenda. Estudios de lengua y literatura españolas 32 (2014): pp. 113–54; Alessandro Serio, ‘Una representación de la crisis de la unión dinástica: los cargos diplomáticos en Roma de Francisco de Rojas y Antonio de Acuña (1501–1507), Cuadernos de historia moderna 32 (2007): pp. 13–29.

[35] Ramírez de Arellano, Las Parroquias de Toledo, p. 13. The expansion was allowed with the proviso that enough space was left unencumbered to ensure an alternative passage. See Paulina López Pita, ‘Fundación de la capilla de la Epifanía en la iglesia de San Andrés de Toledo’, Beresit: Boletín de la Cofradía Internacional de Investigadores 2 (1988): pp. 135, 138. The city was so built-up that in 1538 the city authorities requested the king to prohibit the institution of new hospitals, monasteries or convents within the walls. See Linda Martz and Julio Porres Martín-Cleto, Toledo y los toledanos en 1561 (Toledo: Instituto Provincial de Investigación y Estudios Toledanos, 1974), p. 43.

[36] López Pita, ‘Fundación de la capilla de la Epifanía’; Paulina López Pita, ‘Francisco de Rojas y su vinculación con la Orden de Calatrava’, in Jerónimo López-Salazar Pérez (ed.), Las órdenes militares en la Península Ibérica, vol. 2, Edad Moderna (Toledo: Ediciones de la Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha, 2000), pp. 2229, 2231.

[37] Consejos, 32586, leg. 3, no. 10, fols. 242–42v, AHN; Inocencio Cadiñanos Bardeci, ‘Precisiones acerca del Tránsito de la Virgen de Juan Correa de Vivar’, Boletín del Museo del Prado 24:42 (2006): p. 12n4.

[38] Verardo García Rey, ‘Historia de la pintura española. Fe de errores a una obra’, Arte Español. Revista de la sociedad de amigos del arte 19:2 (1930): p. 58, doc. 1; Duke of Berwick and Alba (ed.), Noticias históricas y genealógicas de los estados de Montijo y Teba, según los documentos de sus archivos (Madrid: Imprenta Alemana, 1915), 20: p. 75; Francisco de Borja de San Román, ‘Documentos inéditos. Testamento del maestro Juan Francés (23 de diciembre 1518)’, Toletum: Boletín de la Real Academia de Bellas Artes y Ciencias Históricas de Toledo 18/19 (1924): p. 111.

[39] López Pita, ‘Fundación de la capilla de la Epifanía’, pp. 132–33.

[40] Leg. 23, no. 1, Archivo Conde de Mora, in López Pita, ‘Fundación de la capilla de la Epifanía’, p. 135.

[41] López Pita, ‘Fundación de la capilla de la Epifanía’, pp. 138–41.

[42] López Pita, ‘Fundación de la capilla de la Epifanía’, p. 142.

[43] Notably, López Pita, Layos; ‘Fundación de la capilla de la Epifanía’; ‘Francisco de Rojas y su vinculación con la Orden de Calatrava’.

[44] Ramírez de Arellano, Las Parroquias de Toledo; García Rey, ‘Historia de la pintura española. Fe de errores a una obra’.

[45] Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo, Batallas y quinquagenas, edited by José Amador de los Ríos y Padilla and Juan Pérez de Tudela y Bueso (Madrid: Real Academia de la Historia, 1983), p. 271.

[46] For example López Pita, Layos.

[47] ‘Testamento que hicieron Alfonso de Caceres…y Doña Marina de Roxas…’ (22 May 1475), Consejos, 23827, leg. 1, no. 7, AHN, esp. fol. 9v.

[48] Jean-Pierre Molénat, ‘La volonté de durer: majorats et chapellenies dans la pratique tolédane des XIIIe–XVe siècles’, En la España medieval 9 (1986): p. 690.

[49] Pedro de Rojas, Discursos ilustres, históricos i genealógicos (Toledo: Ioan Ruiz de Pereda, 1636), 172v. Pedro de Rojas, knight of Calatrava, count of Mora and lord of Layos, was a descendant who wrote a history of the family in the seventeenth century. He listed the children of Alonso de Cáceres and Marina de Rojas in a section dedicated to the surname Escobar, yet styled each of them as ‘Rojas’, including ‘Alonso Escobar y Rojas’. Adoption of the Rojas name was a condition for inheriting the mayorazgos of Layos and Móstoles. See Paulina López Pita, ‘Fundación del Mayorazgo de Móstoles’, Anales toledanos 25 (1988): pp. 100–1.

[50] López Pita, Layos, p. 61.

[51] López Pita, ‘Francisco de Rojas y su vinculación con la Orden de Calatrava’, p. 2227; Francisco Fernández Izquierdo, La orden militar de Calatrava en el siglo XVI: infraestructura institucional, sociología y prosopografía de sus caballeros (Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, 1992), p. 64.

[52] López Pita, Layos, p. 61.

[53] The codicils are dated to 15 June 1492, 7 April 1494, 14 September 1495 and 17 January 1498. See ‘Cuaderno de codicilo que dio Doña Marina de Rojas, mujer que fue de Alfonso de Cáceres’, Consejos, 23827, leg. 1, no. 9, AHN, especially the first, second and fourth codicils, fols. 3, 5, 8.

[54] ‘Cuaderno de codicilo que dio Doña Marina de Rojas, mujer que fue de Alfonso de Cáceres’, Consejos, 23827, leg. 1, no. 9, AHN, especially the first and third codicils, fols. 2, 6.

[55] Fernández Izquierdo, La orden militar de Calatrava en el siglo XVI, p. 122ff.

[56] ‘Testamento que hicieron Alfonso de Caceres…y Doña Marina de Roxas…’ (22 May 1475), Consejos, 23827, leg. 1, no. 7, fol. 3v, AHN. In 1514 Alonso would nevertheless transfer from Santiago to Calatrava, as suggested by a royal permission he obtained for the purpose. Duke of Berwick and Alba, Noticias históricas y genealógicas, 39: p. 93.

[57] As evident from the wills preserved in Consejos, 23827, AHN.

[58] ‘Testamento que hicieron Alfonso de Caceres…y Doña Marina de Roxas…’ (22 May 1475), Consejos, 23827, leg. 1, no. 7, fols. 4–5v, AHN. For information about Francisco de Rojas’s studies and career, see Fernández de Córdova Miralles, ‘Diplomáticos y letrados en Roma al servicio de los Reyes Católicos’, esp. p. 128; Jesús Félix Pascual Molina and Irune Fiz Fuertes, ‘Don Francisco de Rojas, embajador de los Reyes Católicos, y sus empresas artísticas: a propósito de una traza de Juan de Borgoña y Antonio de Comontes’, Boletín del Seminario de Estudios de Arte y Arqueología: BSAA Arte 81 (2015): p. 61.

[59] According to Pedro de Rojas, Francisco’s first military campaign took place in 1475, during the War of Succession. Pedro de Rojas, Discursos ilustres (Toledo: Ioan Ruiz de Pereda, 1636), 200v.

[60] Antonio Rodríguez Villa (ed.), D. Francisco de Rojas, embajador de los Reyes Católicos. Documentos justificativos (Alicante: Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes, 2006), pp. 8–9, accessed 10 March 2019, http://www.cervantesvirtual.com/nd/ark:/59851/bmcks732. For the battle of Loja, Edwards, The Spain of the Catholic Monarchs, p. 105.

[61] Fernández de Córdova Miralles, ‘Diplomáticos y letrados en Roma’, p. 131.

[62] Faustino Menéndez Pidal de Navascués, ‘Las armas de los Reyes Católicos’, Hidalgos: la revista de la Real Asociación de Hidalgos de España 525 (2011): p. 24.

[63] The inscriptions are transcribed in Antolín Abad Pérez, ‘San Juan de los Reyes en la historia, la literatura y el arte’, Anales toledanos 11 (1976): p. 169.

[64] Alonso de Escobar’s will for example requested the arms of Escobar, Rojas, Ribera, Guzmán, Roelas and Gadieles to be placed above the sepulchre he would share with his wife Constanza de Ribera. ‘Testamento que hiço Alonso de Escobar’ (27 January 1531), Consejos, 32586, AHN.

[65] British Library, Add MS 18851 (‘The Breviary of the Queen of Castile’), fols. 436v–37r; Janet Backhouse, The Isabella Breviary (London: The British Library, 1993), pp. 12, 17.

[66] The inscription reads: ‘El muy noble caballero Francisco de Royas mandó fundar esta capilla para reposo de sus padres y delos susçesores dellos, estando en Roma por embaxador de los muy católicos Reyes y Señores Don Fernando e Doña Isabel, Rey y Reyna de las Españas e de las Siçilias aquen e allende el faro e de Jerusalem, negociando entre otros muy ardos negocios de sus magestades e por su mandado la empresa y conquista del dicho Reyno de Siçilia aquende el faro que vulgarmente llaman el reyno de Napoles y Jerusalem, la qual y todas las victorias puso al servicio de las Santisima Trinidad y de la gloriosisima Virgen Santa María, Nuestro Señor y de todos los Santos’. López Pita, Layos, p. 113.

[67] Ramírez de Arellano, Las Parroquias de Toledo, p. 15; Balbina Martínez Caviró, El Monasterio de San Juan de los Reyes (Bilbao: Iberdrola, 2002), pp. 13–14.

[68] Ortiz Pradas, San Juan de los Reyes de Toledo, p. 196.

[69] Domínguez Casas, ‘San Juan de Los Reyes: espacio funerario y aposento regio’, p. 366.

[70] Rafael Domínguez Casas, ‘Exequias borgoñonas en tiempos de Juana I de Castilla’, in Miguel Ángel Zalama Rodríguez (ed.), Juana I en Tordesillas: su mundo, su entorno (Valladolid: Ayuntamiento de Tordesillas, 2010), pp. 262, 265 and passim; Javier Arias Nevado, ‘El papel de los emblemas heráldicos en las ceremonias funerarias de la Edad Media (siglos XIII–XVI)’, En la España medieval 1 (2006): pp. 49–80.

[71] Martín de Riquer, Heráldica castellana en tiempo de los Reyes Católicos (Barcelona: Quaderns Crema, 1986), p. 48.

[72] A transcription of the letter in Duke of Berwick and Alba (ed.), Noticias históricas y genealógicas, 19: p. 73. On the succession of the orders, see María José Lop Otín, ‘Las autoridades eclesiásticas de Toledo y las órdenes militares a fines del siglo XV’, in Ricardo Izquierdo Benito and Francisco Ruiz Gómez (eds.), Las órdenes militares en la Península Ibérica, vol. 1, Edad Media (Toledo: Ediciones de la Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha, 2000), p. 1074. On the architectural history of the convent in the early sixteenth century, see Clara Delgado Valero, Yolanda Guerrero, Francisco Masa and Blanca Piquero, ‘La iglesia de Santiago en el convento de Santa Fe, de Toledo: una obra documentada de Antón Egas,’ Goya: Revista de arte 211/212 (1989): pp. 34–43.

[73] López Pita, ‘Fundación de la capilla de la Epifanía’, p. 132.

[74] López Pita, ‘Fundación de la capilla de la Epifanía’, p. 141.

[75] López Pita, Layos, Appendix, p. 256.

[76] Very little survives of the chapel today. A detailed description is however contained in an anonymous manuscript of 1644. Vicente Castañeda y Alcover, ‘Descripción del sacro convento de Calatrava la Nueva’, Boletín de la Real Academia de la Historia 28 (1928): pp. 402–43. For an extensive discussion of the chapel, its patron and decoration, see Irune Fiz Fuertes and Jesús Félix Pascual Molina, ‘La Capilla Dorada del convento de Calatrava la Nueva. Precisiones iconográficas y patronazgo’, Anuario del Departamento de Historia y Teoría del Arte 28 (2016): pp. 97–112, accessed 12 September 2018, doi:10.15366/anuario2016.28.005.

[77] Ramírez de Arellano, Las Parroquias de Toledo, p. 12.

[78] Juan Guas, Capilla mayor de San Juan de los Reyes, Toledo, 1485–1490, Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado, D00552.

[79] For a more extensive discussion of the drawing’s artificial perspective, Sergio Sanabria, ‘A late Gothic drawing of San Juan de los Reyes in Toledo at the Prado Museum in Madrid,’ Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 51:2 (1992): pp. 161–73.

[80] Domínguez Casas, ‘San Juan de Los Reyes: espacio funerario y aposento regio’, p. 366.

[81] ‘Capilla de la Santa Epifanía en la Iglesia Parroquial de San Andrés de Toledo. Copia autorizada de las constituciones y modificaciones en ellas introducidas en virtud de la bula de Clemente VII’, IV/1863, ADT, especially ‘Las fiestas de la capilla. Cómo se han de celebrar’, VII–IX; see also the earlier regulations established by Francisco de Rojas, transcribed in López Pita, Layos, p. 109.

DOI: 10.33999/2019.52