Hana Rousová is a Czech art historian who has worked as curator of the Prague City Gallery and as main curator of the Modern and Contemporary Art Collection at the National Gallery in Prague. The two texts that follow are excerpts from Rousová’s monograph A(bs)traction: The Czech Lands Amid the Centres of Modernity 1918–1950: Not Only on the Relationships Between the Fine and Applied Arts (A(bs)trakce: Čechy mezi centry modernity 1918–1950: Nejen o vztazích volného a užitého umění), published in 2015.[1] The first text, the book’s introduction, establishes a highly-contextualised art-historical methodology based on ideas of connection and attraction. Rousová is particularly interested in the role of abstraction in the interrelation between fine art and industrial or applied art. ‘The Decoration of Decorative Art’ is a piece of investigative scholarship that uses two abstract artists to explore this interrelation. Its first ‘story’ concerns Czech painter František Kupka and the strangely little-noted fact that abstract work by him appeared in a display of interior design at the 1925 Paris International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts (Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes). Rousová writes of this use of Kupka’s work as a case of painting seen as decorative object, an approach by no means limited to this example. The second ‘story’ concerns a music room designed by Vasilii Kandinsky and exhibited at the German building exhibition (Deutsche Bauasstellung) organised by Bauhaus in 1931. Noting the irony that this piece of applied abstraction has been celebrated as an important example of ‘Kandinsky’s art’, Rousová situates the work in a wider concern among designers with private music rooms—with ‘the culture of everyday life’—and yet shows how Kandinsky’s cultivation of ‘ornamentality’ resisted the dominant design aesthetics of his era. (JO)

A(bs)traction: The Czech Lands Amid the Centres of Modernity 1918–1950, Part 1: (Not Only) on the Relationships Between the Fine and Applied Arts [Introduction]

Hana Rousová

What I want to describe does not resemble truth. At the same time, it is pure truth, if by “truth” we mean something that was or is. If, however, we consider it useful to distinguish truth from fact, then of course it was not exactly thus.

Oleksandr Dovzhenko, 1953[2]

A(bs)TRACTION → ABSTRACTION / ATTRACTION / TRACTION

Abstraction: An art form without syuzhet (subject) or correspondence to specific objects. It can be ambivalently attractive; can have the potential for meaning or decoration; be unique or easily imitated; be usable. Kazimir Malevich, 1913: ‘In the year 1913, in my desperate attempt to free art from the ballast of objectivity, I took refuge in the square form and exhibited a picture which consisted of nothing more than a black square on a white field’.[3] Paul Klee, 1914: ‘The cool Romanticism of this style without pathos is unheard of. The more horrible this world (as today, for instance), the more abstract our art, whereas a happy world brings forth an art of the here and now’.[4] El Lissitzky, 1919: ‘When the image is liberated by “pure”, “abstract”, “objectless” painting, it is thereby buried with finality. But the artist begins to reshape himself. Instead of one who reproduces, the artist is transformed into the creator of a new world of forms, a new world of objects’.[5] Robert Delaunay, after 1920: ‘I make no dividing line between painting and sculpture. All is colour in motion; it is a construction of what I call simultaneous depiction’.[6] Sonia Delaunay expanded the territory of painting and sculpture to include fashion, Jean Fouquet added jewellery based on the principles of geometric abstraction, and Alvar Alto, together with anonymous factory designers, added objects with organic shapes.

Virtual reality, abstract, simulated. It means an illusion of the real world, enabling one to live someone else’s life; a means of manipulation that existed long before electronic media.

Attraction: Sergei Eisenstein’s montage of attractions. He wrote of montage: ‘For me montage is a collision, a collision between two elements from which a meaning arises’.[7] The objective is to disrupt the plot construction and draw attention to parts of the whole. Attraction entails an internal contradiction and its unexpected disclosure.[8] Eistenstein wrote: ‘I think the thing is that I was particularly captivated by the nature of the non-correlation of fragments which nevertheless, and often despite their nature, when combined with the will of the editor gave rise to ‘a third thing’ and became correlated’.[9]

Using the montage of attractions as a method of art-historical work means bringing together works that ordinarily do not come together in the ‘plot construction’ of art history, and the coming together of words, not only about the works but citations of authentic thoughts from the past and present. It means connecting the unconnected across disciplines as well as across the flow of time; attempting to be screenwriter, director, and also editor; wandering through the landscapes of human creativity, defying systemisation and unequivocal comprehension; being ‘captivated’ by them without succumbing to blindness towards their social and political determination.

But it perhaps also entails the more contemporary tool, adopted from electronic media, of ‘flipping’. To flip whole layers horizontally or vertically, or selections from them or paths to them, thus changing their sense. Similarly, as in the case of the montage-attraction, to wager on the potential openness of the process of creating new correlations.

Traction: Pull. Not only one-directional, in which the stronger pulls the weaker. The question is: who is actually the stronger? And is it necessary to ask that at all?[10]

The Czech Lands Amid the Centres of Modernity 1918–1950

Czech lands: Lands within the area of the Czech Republic and also within the context of the former Czechoslovakia.

Centres of modernity: Vienna, Berlin, Paris, Moscow. Berlin and Moscow changed their positions during the totalitarian regimes, when they turned from places of inspiration into centres of invasive destruction.

Modernity: In contrast to the term ‘modern’, this term has a wider meaning and concerns the organisation of social life. It is linked to the certain time and place when and where it emerged. According to Anthony Giddens, modernity leads to the deconstruction of an evolutionary view of society: it ‘means accepting that history cannot be seen as a unity, or as reflecting certain unifying principles of organisation and transformation’.[11] And, simultaneously, ‘the advent of modernity increasingly tears space away from place by fostering relations between “absent” others, locationally distant from any given situation of face-to-face interaction … What structures the locale is not simply that which is present on the scene; the “visible form” of the locale conceals the distanciated relations which determine its nature’.[12]

1918–1950: The period in which modernity fully revealed both its light and dark faces. Positive, prospective thinking that, despite opposing concepts, never ceases to fascinate us, and, paradoxically, the devaluation of humanistic values built on the same foundations. We reject this modernity and yet it remains potentially present. To grasp the past by a present method, to animate it for the present, is one of the main objectives of this work.

(Not Only) on the Relations Between the Fine and the Applied Arts

In the beginning there was a story; a little comic, a little strange, in itself not particularly interesting. Yet in its details, or rather in their chance connection, it precisely illustrated the often-paradoxical geopolitical aspects of Czech history and the penetration of artistic styles across time, including sometimes improbable ones. It was this that gave me the definitive impulse to write a book about themes that I had previously dealt with several times, but only in a partial manner.

Story

Some time ago, and purely by chance, I got hold of a copy of the French magazine Art et Décoration from 1929, which had come from the library of Stanislav Remeš. Remeš graduated from the Academy of Arts, Architecture, and Design in Prague in 1955, and later devoted himself to animated films. In the 1960s he also created several film posters. How he acquired Art et Décoration I do not know; most likely he bought it after the war in some second-hand bookshop. It interested him and proved useful to him. He left a direct testimony of this in the magazine itself: he inserted a letter and several small sketches into it. The letter is written on the headed notepaper of the Kavalier glassworks, a national enterprise based in Sázava, and is dated 8 February 1949. It is addressed to ‘Comrade Stanislav Remeš, soldier, Military History Institute, Prague 11, Husova 1600’. A certain Pavel, evidently a friend, asked Remeš (who was at this time spending his military service at the Military History Institute in the role of designer) in this letter to create a design quickly for a new and, crucially, more modern headed notepaper for the glassworks. Remeš attempted this and took inspiration from what he had to hand. He leafed through the Art et Décoration magazine, where, besides an article about Czech book covers,[13] he found a sampler of stylish fonts from the late 1920s by the famous designer Cassandre.[14] One font in particular appealed to him and, perhaps with a certain degree of mischief, he used it in several variations of his design. He drew it on the back of forms, printed in Gothic script, for the German health insurance system that operated in Prague during the protectorate. Such forms were available in countless numbers at protectorate offices and businesses. As far as I could ascertain, none of Remeš’s designs were put into print. It is more than probable that, to the ‘enlightened’ management of the recently-nationalised glassworks, they seemed too modern and suspiciously bourgeois. Of course, this was not far from the truth.

Theme

I am concerned with the fine art of the 1920s–1940s, including abstract painting and sculpture. A long time ago I noticed an interesting phenomenon, which is the transfer of abstraction, especially in painted form, to the applied arts. If I use the word ‘transfer’ in this book, however, it is not one-sidedly, but in the context of mutual interaction between artistic disciplines. Art-historical research led me to a differentiation of the issue as well as to considerations of abstraction as a general principal, which, through a departure from the exclusive space of the studios and exhibition halls to other areas of social life, surpasses its morphological and authorial context and acquires new roles. It was these that opened up for me an almost infinite space of consequences and, with them, surprising relationships that often behave towards the standards of art history almost blasphemously, provocatively and insolently. I was afforded a view that fascinated me. Yes, a view, because at first these were visual encounters. It was only afterwards that there came the stress of questions as to how to name these encounters, how to deal with them within the bounds of the existing scheme of the art work, or how to transcend that scheme, and, last but not least, what socio-political and cultural-historical dimensions they have. I chose for this a concept whose fundamental theses are encapsulated in the title and subtitle of the book. This book is structured in accordance with the meaning of those words and, especially, with the contrapuntal rhythm with which they are phrased (abstraction – attraction)

Choice

The choice of abstraction from the options of mutual relations between the fine and applied arts did not, however, sufficiently narrow the theme. It was necessary to specify it more closely. I did not find (and I confess that I did not really seek) some objective key. The selection of the phenomena I am examining is my personal choice. At the same time, I can imagine others, with differently posed questions and different demonstrations. All the more reason why I deliberately balance these phenomena on their edge and, in some cases, by means of apparently inappropriate excursions, disrupt their artificially-created construction. I want to give them a chance to return to an original space, unburdened by interpretations.

Authorship and Anonymity

My research indicated that rather than interdisciplinary links between the original authors’ conceptions, an aspect that is often more interesting is the loose reflections of these conceptions by serial production designers in the factory, namely, those who were regarded as ordinary workers and were obliged to remain anonymous. With growing factory production, a new, vigorous multiplicity appeared on the scene, with ambitions to oppose the preferential status of authorial performance and the sovereign status of the unique work of art. The emergence of consumer culture led to changes in assessment criteria and, alongside them, in marketing strategies, taking into account social position, cultural preferences and, last but not least, the purchasing power of the customer, the increasingly socially-significant middle class. Influence on the mentality and lifestyle of the broadest segments of the public was paramount. Therefore, it was in the field of industrial production that fundamental collisions occurred between the modernist and anti-modernist programmes.

Contexts

Industrialisation (admired as well as condemned); its hopes and falls; the belief in a better future; and disillusion; the power of the collective and the power of personality; historical events and their impact on society and on individual destinies. These constitute contexts without which cultural events (and not only these) would not have taken the direction they did. The theme of abstraction has something to say about all these things: sometimes a great deal, sometimes a mere footnote. This book, however, offers no construct that would exhaust, unconditionally classify, and systematise the symptoms of the chosen issue. It is an attempt to test the openness of the discipline called the history of art.

English version edited by Jonathan Owen

A(bs)traction: The Czech Lands Amid the Centres of Modernity 1918–1950, Part 2: The Decoration of Decorative Art

Hana Rousová

Due to misunderstanding or even by mistake, the boundaries between fine and applied art have often become blurred in paradoxical ways. Decorative qualities have been attributed to pieces that were created for diametrically opposite reasons, while, conversely, pieces that were intended as decoration have been received as independent works. There are two stories that provide particularly vivid examples of both such situations. In the first, František Kupka’s abstract paintings became decorations by chance and no-one noticed them. In the second, Vasilii Kandinsky programmatically applied the principles of his abstractions to a decorative work, whose aim moreover was advertising, and this latter work was written about by all the important European journals as a further significant example of Kandinsky’s art.

The First Story: František Kupka in the Role of Interior Decorator

In the library of the Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague there is a group of photographs by an unknown author who, in 1925, was entrusted with documenting the installation of the Czechoslovak pavilion at the International Exhibition of Modern and Decorative Arts (Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes) in Paris. One shot shows a simulation of a smoking lounge, whose corner-centred layout is emphasised by Bohumil Kafka’s bronze sculpture Somnambulist (Somnambula, 1905) and whose walls are ‘decorated’ by František Kupka’s paintings A Tale of Pistils and Stamens (Příběh o pestících a tyčinkách, 1919–20) and Study for the Language of Verticals (Studie k Mluvě kolmic, 1911) (Fig. 6.1). But, in contrast to the furniture and the small sculptures, Kupka’s abstractions hang there without any identifying labels, quite anonymously.[15] It is true that a very observant spectator might possibly, on closer examination, notice Kupka’s signature, but who would have had time for that whilst viewing this mega-exhibition?

My research into how such surprisingly-inappropriate treatment of his works has been assessed by existing scholarly works about Kupka led to a discovery that is perhaps even more surprising: none of these works mention Kupka’s inclusion in this exhibition, even while biographies of Kupka have long claimed to be complete.[16] This makes more interesting the question of how Kupka, known for his sense of exclusiveness and his fusion of the principles of artistic creation with the laws of the cosmos, and whose confessional text Creation in Visual Art (Tvoření v umění výtvarném, 1923) had been published by the Mánes Union of Fine Arts (SVU Mánes) shortly beforehand, found himself at an exhibition of decorative art, yet was not invited to participate in an opposing exhibition, ‘The Art of Today’ (‘L’Art d’aujourd’hui’), which was staged in Paris at the same time by the international avant-garde.[17] Finding the answer to this entailed an extensive investigation that, because of its detective story-like plot, is worth recounting in more detail. This is a story about a story.

First, I discovered that Kupka’s name does not appear either in the catalogue for the Czechoslovak pavilion or in the huge list of awarded artists published by the exhibition’s French organisers.[18] Nearly all the artists involved in the exhibition received medals, but nobody registered Kupka’s participation, not even reviews in the Czech press. Several of these appeared almost immediately, and the most competent of them was probably Pavel Janák’s extensive article ‘The Exhibition in Paris, The Art Industry and Life’, from the journal Výtvarná práce (Art Work).[19] Janák devoted thorough and dedicated attention to the exhibition, with particular regard to stylistic trends in interior design, but, like other reviewers, he did not notice Kupka’s abstractions. I therefore turned my investigations to Václav Vilém Štech, the chief curator of the Czechoslovak exposition, but this did not lead anywhere either. Štech expressed his opinions on almost everything, but Kupka clearly never interested him. It therefore seemed unlikely that it was he who had invited Kupka to exhibit his pictures, but given Štech’s authoritative position he surely had to figure in this story somehow.

Both pictures were Kupka’s own property at this time, and Study for the Language of Verticals from 1911 had not even been exhibited yet.[20] Kupka would thus have had to supply the pictures to the organisers of the Czechoslovak exposition himself. But why and at what stage of the preparations? We know that in the original conception for the exposition, as documented in its catalogue, these pictures were not included. The first constructive clues were ultimately offered by several of Kupka’s letters to Jindřich Waldes.[21] These show that the story really began by chance, that it had its source in something of a misunderstanding, and that it was connected to Kupka’s pedagogical work with Czech students studying on scholarships in Paris. Several passages in these letters give an authentic insight into the contradictory nature of Kupka’s personality and enable us to grasp the reasons why he agreed to the use of his pictures as decoration.

On 12 December 1923 Kupka wrote to Waldes, a little emotionally:

My studio is serving as a classroom and such small acts of hospitality bring joy, as the majority of them [the students] are not wealthy. Of course this will all straighten itself out; in the meantime I am being paid back for all this in the sympathy and dedication of these good young souls, with whose help I am transmitting to Prague a sense of the recognition of individual dignity and, for the artists, a hatred of every plagiarisation of the latest fashionable phenomena … Recently these artists have mainly manifested impatience at my scorning of publicity … I am too much of a philosopher, and otherwise I am not too aware of all that I would bring upon myself if I engaged in open battle with rotten traditions and with all these rotten heads, for whom a revolution means a reversal of many comforts. People such as I get burned, so do not be surprised that I am in no hurry. Now, in my own concept of life, I stand tall enough: if I do not get to see these wider successes while still alive, I would not be hurt to know that this will happen only after my death. My “I” is not confined to my body, but already travels far into the universe.[22]

But, about a month later, an affronted Kupka changed his attitude:

Over the next year I’ll be preparing an exhibition in which I will throw down my trump cards. Yesterday I was visited by this young Czech girl painter. She is a student of Fern[and] Léger and she spoke of him as though of a great Master. This Léger is unthinkable without me, but since he turns it all into something more marketable, even a stupid fly like her gets stuck as if on glue. I will endure this! … For the truth always wins. Gleizes will get one on the nose and so will Picasso and others.[23]

The Stupid Fly

Who was this ‘stupid fly’? It could not have been any of Kupka’s numerous female students of that time, who, besides the painter Milada Marešová and the sculptor Marta Jirásková, were so nondescript, and whose interest in painting was so short-lived, that they did not even make it into Prokop Toman’s Dictionary of Fine Artists (Slovníku výtvarných umělců) (and that is saying something). It was Věra Jičínská. Not only was Jičínská not in any way stupid, but, as we shall see later, it was most probably thanks to her that Kupka got to exhibit his pictures at the Czechoslovak pavilion.

An open, lively, and educated girl, Jičinská began to visit Léger’s school at the beginning of 1924.[24] She explained her attitude towards art schools in the following way to Vladimír Maisner, her friend at the time: ‘I move between schools, I find it wonderfully interesting to get to know about different opinions and trends and I feel that I can learn something from each of them’.[25] In another part of this letter she describes her meeting with Kupka, who, incidentally, as is evident from his correspondence, still spoke Czech very well:

It will perhaps also interest you that I visited the painter Kupka. But to tell the truth, I was disappointed. I don’t know, but many of my opinions were contrary to his and, though I was forced to speak in French, I got terribly incensed and I zealously (perhaps too much so) opposed his ideas to such an extent that we parted on rather unfriendly terms. He is doing very interesting things at the moment. His use of colour is very pretty and decorative, but I think this is more suited to paintings on walls than on canvases … So this Kupka advised me to work independently (which I approve of), without academies, and doesn’t grasp that I can change my teachers. Apparently I am supposed to remain with the same one and to retain my impressions from youth, these being the strongest ones (so perhaps my teacher should be Úprka forever!!) … I understood from all this that I should remain in Prague, not go to any school and work alone. This is all very nice, it is just that I don’t understand why he accepted a professorial post and why he is now living in Paris. I don’t understand him then, but it is not only me, other Czechs have also been a little disappointed by him.[26]

Despite this mutual misunderstanding, which certainly also reflected a generational difference, Jičínská still visited Kupka’s studio from time to time up until 1925. Maybe she was ultimately able to win Kupka’s favour in some way. But she was seven years younger than him and definitely did not want to take up residence, as he had done, in some ‘sacred ivory tower’.[27] On the contrary, she was irresistibly drawn to the discordant features of modern civilisation:

I think that life today has little of the lyrical, and I love this awful rush, this bustle, this cry of the metropolis. This disharmony makes me feel terribly good. You know, to immerse myself sometimes in this din, among these automobiles, trams, buses, amid the cry, the racket, the honking horns. There someone fell down, here they ran over someone again, someone drowned, the Seine flooded, people move about, the Dixmude crashed, murder, fire and water, everything all together—this grand disharmony culminates in the despairing cry of the modern man. You know, I’m able to get caught up in all this, and yet if I am at a concert listening to Beethoven, Liszt or Chopin, I feel contentment, peace.[28]

As we can see, it would be a mistake to see Jičínská’s letters only as evidential material. They have their own literary style, a distinctive imagination and a well-defined idea of the values of the modern era, which was in essence very similar to the one held by the leading artistic personalities of that time. These letters thus clearly formulate one of the principal reasons why Kupka’s abstract work remained alien for other artists of Jičínská’s generation (however diversely oriented), such as the members of the Czech avant-garde. Having its basis in the art of the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Kupka’s work was now simply incomprehensibly old-fashioned for the majority of young people. This also explains the seemingly mysterious and often-discussed fact that, among Kupka’s numerous students, there was not one who would in some way build on his work.

Virtue from Necessity

The International Exhibition of Modern and Decorative Arts in Paris began to be installed in the spring of 1925. This was a demanding task and the Czechoslovak pavilion became a welcome opportunity for young Czech artists living a modest lifestyle in Paris to earn some extra money. The most actively involved included Věra Jičínská herself, as well as Jičínská’s then-roommate, the sculptor Marta Jirásková. Jičínská worked as a sign-painter, helped with the installation work, and later, during the exhibition, provided information and sold promotional material. She was able to communicate well with her superiors, which proves particularly important for the story of Kupka’s inclusion in the exhibition. Jičínská sent photographs back home, and in these we see her with Václav Vilém Štech and with Adolf Cinek, the administrative secretary for the Czechoslovak section. As she wrote to Maisner: ‘they like me here, they say I am always in a good mood, always cheerful!’[29] She also became friends with Rudolf Kepl, an employee of the Czechoslovak embassy in Paris (who, incidentally, became a cultural attaché after the Second World War, and who was close to the ambassador Štefan Osuský).

Osuský, a big promoter of Czechoslovak culture in France who organised, for instance, a performance of Smetana’s The Bartered Bride (Prodaná nevěsta) at Paris’s national Opéra-Comique theatre to mark the tenth anniversary of the founding of Czechoslovakia, was one of the first collectors of Kupka’s work. According to Emanuel Siblík, in the 1920s Osuský owned not only a number of Kupka’s early works, but also some of his abstractions, including for instance all three variations of the composition Lines, Areas, Depth (Čáry, plochy, hloubka, 1913–1922).[30] The Czechoslovak embassy plays an important role in my further investigations: Jaroslav Šejnoha, the embassy’s first secretary, was appointed as the representative of the Czechoslovak section’s general commissioner, František Hodáč, and this means that the embassy certainly had a highly authoritative standing in the whole affair.

It is certain that Kupka’s pictures were only included in the exhibition at the last minute, but this did not matter to Kupka, and neither did the purpose behind their usage. He evidently revised his opinion about the ‘stupid fly’, and was pleasantly surprised by what suddenly began to happen: ‘my whole situation is taking on a shape that I would never have expected. This is ultimately something unprecedented. While I exercise absolute disregard for the external world, several of my young followers are taking care of things. In a way they are apostles. If things go on like this, I will be able to become a kind of Dalai Lama living in a sacred ivory tower’.[31]

But no such situation would ever recur. This was a one-of-a-kind action, a case of making a virtue from necessity. The Czechoslovak pavilion’s organisers, headed by Štech, had evidently not reckoned with the fact that they would also have to incorporate paintings into their choice of exhibits. Indeed the original French commission had referred exclusively to sculpture, architecture, ceramics, glassware, book illustrations and designs, metalwork, furniture, and fashion. Scenography was later added to these, but there was never any mention of paintings.[32] It was only when on site, during the installation itself, that they realised that the exhibition’s other national pavilions and thematic sections were full of them. They then had to quickly redress the situation. It seems that just at this moment it occurred to Jičínska, along with Jirásková perhaps—these two virtual ‘apostles’—to ask Kupka for some of his paintings. Thanks to her good social contacts Jičínská succeeded in realising this idea. She certainly saw Kupka’s abstractions as predominantly decorative, and this was not her opinion alone. It is probable that they were also seen as such by, for instance, the highly socially active Osuský, whose other favourite painter was the fashionable artist Veris (Jaroslav Zamazal), who painted portraits of Osuský’s family members.

The Painting as Decoration

Emanuel Siblík, in his 1928 monograph on Kupka, thus considered it his duty to refute this evidently commonly-shared opinion. In order to support his views with those of a recognised authority, Siblík quoted the following passage from a text about Kupka by André Gybal, published in 1920 in the journal Les Hommes du jour (Men of the Day): ‘the arabesque is by no means merely decorative. These splendid compositions express the most varied, subtlest and rarest ideas’.[33] It was, however, quite common in the 1920s to consider a painting as a decorative object, and the International Exhibition of Modern and Decorative Arts took full advantage of this. The main issue was not the quality of a painting, but rather whether it fulfilled a basic function: to contribute, in an appropriate fashion, to the decoration of a specific type of environment. And as is ultimately shown by the wealth of documentary material produced about the exhibition by its French organisers, the majority of paintings here, even those by much more famous artists, were installed, as with Kupka’s work, without detailed identification, and thus as ‘mere’ decoration. Many of the pictures had been painted for the exhibition with this very aim. So, contrary to the starting assumptions of my investigations, in truth Kupka’s paintings had not been treated in an unusually-dismissive manner by this exhibition.

Moreover, why should Kupka not have been happy, when, besides the opportunity he was given to exhibit his abstractions within such a highly-visited forum, he also found himself in such very good company? In fact, the painter who really triumphed at the exhibition, and the only one who received a gold medal in the field of painting, was the ‘great Master’ himself, Fernand Léger. Because he then belonged to the Purists, Léger’s work was used predominantly to decorate the Le Corbusier-designed L’Esprit Nouveau pavilion with geometric abstraction. This comprised one of Léger’s first mural paintings. He also painted a giant orthogonal abstraction for the entrance hall of the so-called ‘French embassy’, intended to be the dominant element of French national representation at the exhibition.[34] Another wall of the hall was handled by Robert Delaunay, who added one of his numerous Eiffel Tower paintings, which was similar, for instance, to the one that had shortly before adorned a newly-opened chic Paris bar. The journal L’Art vivant (The Living Art) printed an admiring report about Delaunay’s piece.

Finally, I wish to comment on the startling fact that Kupka’s participation in the International Exhibition of Modern and Decorative Arts continues to be ignored by Czech art historians. This is possibly because these art historians—held captive to traditional evaluative criteria determining what is and is not art, criteria that a hundred years of discussion has not managed to shake—consider his participation as discrediting. And what of Kupka’s contemporaries? We need perhaps only add that Czechs were usually not too aware of their compatriots who were living abroad, and when it came to it, did not even recognise their work. At least this was true in the 1920s, as is attested by another story, one that may be minor but is all the more indicative for that and reflects very strangely on the then-recent Art Nouveau style. In 1929, in the journal Eva, the 24-year-old Zdeněk Macek enthusiastically described his visit to the Paris shop of the famous jeweller Georges Fouquet. In his conclusion Macek boasted that ‘it was a delight to sit amid the musty gold of the Louis XV armchairs’.[35] All very nice, except that in reality Macek was sitting in an interior designed in its entirety by Alphonse Mucha in 1901. It is true that over the previous 20 years there had been radical changes in design (and not only in design), but how could the Art Nouveau image have fallen back several centuries in time and, with it, Macek’s still-living compatriot, even if Mucha now had his most attractive work behind him? Since restored and relocated, the interior of the shop is now among the important exhibits of the Carnavalet Museum.

The Second Story: Wasily Kandinsky and Ceramic Tiles

When Pavel Janák reviewed the International Exhibition of Modern and Decorative Arts in Paris in 1925, concentrating first and foremost on the housing strategies presented, what predominantly concerned him was their preference for luxury. Quality designers were, as they are today, generally dependent on wealthy clients. Their designs, expensive and complex to produce, were not suited to the large-scale factory production that would have made them accessible to the wider public. Prompted by the same reaction as Janák, the idea arose in Germany that year of organising another exhibition, opposed to the Paris one on the issue of exclusive luxury: an exhibition whose theme would be ‘the dwelling of our time’, or housing ‘for the many’ (the expanding middle class). This exhibition first took concrete shape thanks to the architects Hans Poelzig, an important exponent of German Expressionist architecture, and Martin Wagner, a designer of early, modernist-style Berlin housing estates. The organisation of the exhibition was ultimately taken over by representatives of Bauhaus in Dessau, led by Ludwig Mies van der Roh and Lilly Reich. As is evident from photographic documentation that follows the exhibition’s development from the initial building work up to its final form, the results must have been spectacular, and this is also attested by contemporaneous accounts. The exhibition lasted from May to July 1931 and its name was the German Building Exhibition Berlin 1931 (Deutsche Bauausstellung Berlin 1931). Although other countries were represented at the exhibition, German projects predominated. The exhibition featured interesting, graphically-designed and, in several places, interactive panels featuring diagrams and photomontages on the themes of housing, work, and environment, and expositions of clocks and books by Walter Gropius, Marcel Breuer, brothers Hans and Wassili Luckhardt, Ludwig Hilberseimer, Josef Albers and others. It was—according to the testimony of architect Jan Evangelista Koula, who confirms the impression given by photographs—a display of:

contemporary housing demonstrated with models, which were built in real size and placed inside the audacious construction of a hall of reinforced concrete … The exhibition was not generally aimed at professionals; it was intended predominantly for the lay public, on whom it impressed important items of knowledge by putting these in a popular, and often very effective, form … It seems to me that in Germany it is important that citizens be well-informed about everything connected with modern-day construction, and thus about architectural questions, economic questions, etc., and that they realise that this is a matter of their work and property, of their better future.[36]

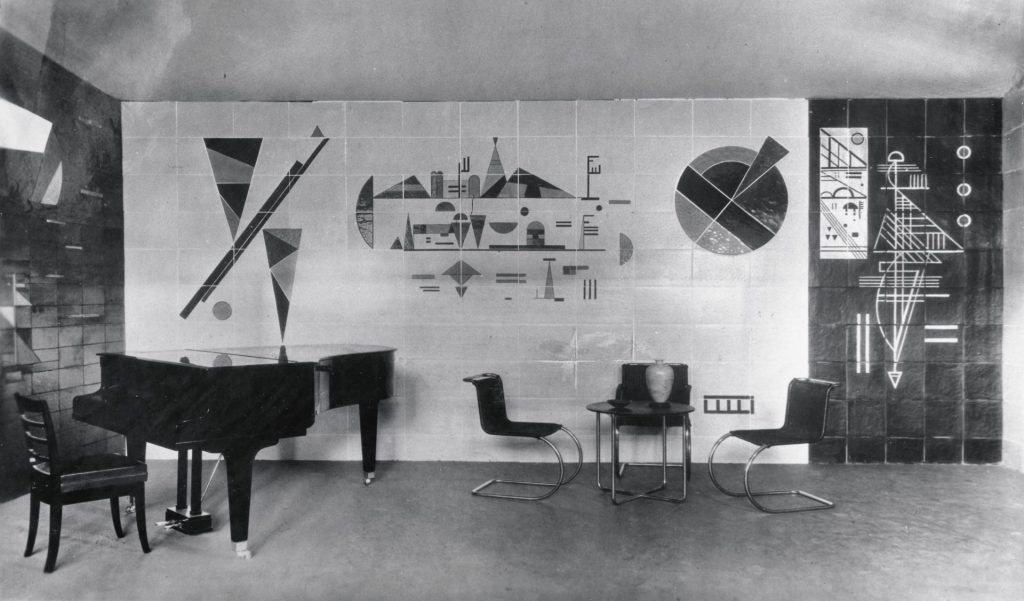

As another reviewer, this time German, wrote in Keramische Rundschau (Ceramic Review), ‘hall II at the Building Exhibition in Berlin was devoted to the theme “The Dwelling of Our Time”. Here the floor was given to leading architects and interior designers, who presented a range of designs for apartments and living spaces, which deal with the present and future issues of habitation in its many-sided complexity’. Yet this reviewer also asserted in his article that ‘the so-called romance of the “cold wall” can only appeal to a few people outside the artistic circle in which this formulation originates’, and, in accordance with the magazine’s area of focus, stated that, ‘for the circle that has coined this term, ceramics can have no essential significance’. But he then noted: ‘it is thus all the more pleasing that ceramics provided the dominant element in at least one of these modern spaces: in the music room designed by Professor Kandinsky and realised by Oranienburger Werkstätten Körting K.G. Berlin in collaboration with Saxonia AG in Meissen’ (Fig. 6.2).[37]

The Music Room Phenomenon

Before we continue our story about Kandinsky, it would be useful to look briefly at the music room as a phenomenon, one that has long ceased to be classed among the requirements of domestic space. By contrast, in the nineteenth century and afterwards, a music room was one of the ‘regular’ facilities of any bourgeois living quarters. It was used for domestic music production, in essence thus imitating the lifestyle of the nobility on a small scale. In Czechoslovakia after the Second World War, the idea that children (especially girls) from ‘good’ families should learn to play the piano still survived from the days of the First Czechoslovak Republic. The piano, which was usually a grand piano, had to be put somewhere, and there had to be a place where family members and friends could gather and participate in music production. Of course, this included not only children but also adults brought up in this tradition. Depending on the circumstances of the host, professional performers would even be invited too.

The question of how a music room should look was no minor issue for modernist architects. While they protested against the bourgeoisie, among whose relics the music room might to some extent be counted, they also emphasised the culture of everyday life and believed all forms of art should be an essential part of this. At the beginning of the twentieth century, as rented apartments began to get smaller and it seemed that their tenants were starting to prefer the passive experience of going to concerts, the Austrian writer and architectural theorist Joseph August Lux was particularly active in striving to cultivate the playing of music within the home. In a chapter of his book The Modern Apartment and its Furnishings (Die moderne Wohnung und ihre Ausstattung) entitled ‘The Music Room’ (‘Das Musikzimmer’), he used drawings by several architects to demonstrate various ways of arranging a small apartment with this aim in mind; as a last resort he considered simply putting a small piano in the living room.[38] In his conclusion he added some aesthetic advice: ‘if you have the desire and the means to create a music room, then deny yourself any kind of ornamentation … any adornment, and particularly busts of musicians or portraits, because they bring nothing to the musical experience, and are much more likely to disturb’.[39] Modernist architects generally embraced opinions of this kind. For instance, the then-influential handbook Spatial Art in Colour, 100 Designs by Modern Artists (Farbige Raumkunst, 100 Entwürfe moderner Künstler), which was published in periodical form between 1911 and 1942 in Stuttgart, devoted itself regularly to designs for music rooms. These were always relatively large spaces with a piano, comfortable seating, and usually just one artwork, selected in accordance with the room’s design. To realise these designs would of course have entailed considerable expense: certainly only a few people could have afforded them.

Nonetheless, the socially-critical, leftist architect Jiří Kroha included a not-exactly-modest design for a music room—or rather, as he called it, a ‘cultural room’—in his project A Humanist Fragment of Housing (Humanistický fragment bydlení) from the years 1936–1947. Even though it still contained a grand piano, Kroha’s conception of his cultural room also included a different type of domestic music production, which took people’s individual social situations into account. In his article ‘Art in the Apartment’, published in the journal Blok, Kroha discussed the significance of the reproducibility of visual and particularly musical art, which could now be mediated in high-quality form through radio transmissions or gramophone recordings. He justified his aims in the following way:

These new reproductive methods enable a person to return to his apartment for his cultural experiences. Of course, his apartment must be fitted out for this. The conditions thus arise for a free social room as a socially-conventional facility and a higher version of otherwise obsolete historical forms: the palace ballroom, the bourgeois salon, the bourgeois parlour room, the petit-bourgeois occasional room, and the living room of present times, ultimately rationalised but still unsuited to cultural requirements.[40]

Back to Kandinsky

Just like Kroha, the earlier avant-gardists of the Bauhaus circle also, surprisingly, did not consider the music room as a luxury, something not really befitting the social programme of the German Building Exhibition. They probably understood it in the same terms as the Dutch architect Johannes Martinus van Hardeveld, when he asserted: ‘applied art has no social or economic importance outside of its moral influence, such as we find in music’.[41] Most probably, however, they were not all that consistent in their ideas and behaved pragmatically in taking up some exceptionally attractive offers. We learn some details in the previously-cited article, of unknown authorship, from Keramische Rundschau, which is interesting for, among other things, its critical evaluation of Kandinsky’s abstractions, whose inflections are defined as ‘ornamentality’, and also of modernist concepts of the functional and above-all hygienic arrangement of living spaces.[42] These opinions can be considered, paradoxically, as ‘the voice of the people’, of those who, in theory, were meant to be the primary concern in all this:

It is thanks to Mrs. Körting, who has aroused an interest in ceramic material in our modern painters and has thereby helped oppose that unadorned coldness of modern spaces, which accompanies us throughout this exhibition, with the capacity of coloured ceramic material to decorate, enliven and tune the mood of a space. The formal methods of the painter Kandinsky do not, in themselves, have much to say, but it should be admitted that his ornamentality and colour palette, in being reconceived for ceramic material, present a new direction for the role of ceramics in the formation of spaces, and that in the realisation of this music room we find, beyond its individual approach, the fundamental foundations for collaboration between artists, ceramics workshops and the ceramics industry.[43]

The reviewer continued with a very detailed description of the surprisingly-complicated technology that ceramics factory workers had to use to produce the individual parts of this composition. Its base surface was created by what were essentially ordinary tiles, and this was taken apart during the exhibition itself. We should add that ‘Mrs. Körting’ was the wife of the owner of the Oranienburger Werkstätten Körting factory, and that, unlike the reviewer, she was no doubt well aware of why the factory had chosen Kandinsky in particular to realise its aims. As with other firms that were represented at the exhibition, its intention had been to use such a prestigious event to advertise itself, and in a manner it considered attractive. This is attested partly by the choice of a music room, which corresponded to the social level in which the company moved, and partly by the way the exhibit was set up: the room’s arrangement was only indicated, and relied exclusively on the use of walls with ceramic tiles, while the other interiors were generally constructed in full, as life-size models, which was emphasised by the exhibition’s reviewers.[44]

This music room—or more precisely its fragmentary representation—was, besides its piano, furnished with three tubular chairs, which were at this time being serially manufactured by the company Berliner Metallgewerbe, after a design by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. They stood at a small table with a nondescript little vase. There is nothing surprising here given that the artist behind this interior arrangement was Mies himself. In comparison with other projects for music rooms, filled with upholstered lounge suites designed to ensure a comfortable listening experience, this one looked like a dentist’s waiting room.

Between 1922 and 1925 Kandinsky led a mural workshop at Bauhaus, though he himself only produced one mural, shown at the Jury-free Exhibition (Juryfreie Kunstschau) in Berlin in 1922. Later he worked as a teacher of ‘free’ painting. Again he had only one experience of applying his abstractions to décor. This comprised a rather casual collaboration between 1920 and 1923 with the circle around Vladimir Tatlin, then working at the Dulevo porcelain factory. Two designs he produced for decorated teacups and saucers clearly indicate that his abstract-expressive style of that time, in contrast to the geometric minimalism of the Constructivists or the Petrograd-based Suprematists, was not very well suited to such ends.

At the German Building Exhibition Kandinsky set about his assigned task in a pragmatic spirit. His designs for the ceramic walls, employing the geometric-abstract style that now characterised his paintings, were produced, quite atypically, in the form of hanging oil paintings. This freed him from dependence on the manufacturing process and enabled him to make additional use of these works, including further commercial use. Future developments have shown this to be a farsighted move on Kandinsky’s part. Today the paintings belong to the Strasbourg Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, to whom they were donated in 1975 by Societé L’Oréal, together with a replica of the music room itself. The replica was made by the company Villeroy & Boch, one of the few German ceramics factories that survived the war and continues successfully today. The original version of the music room had no such luck.

And how did Kandinsky settle the fact that he had broken Adolf Loos’ fundamental rule of the ‘bare wall’, a rule that was still binding after 20 years (and not only for the Functionalist architects represented at the exhibition) and which remained an enduring topic of discussion? It could be said that he cleverly escaped censure. In the exhibition catalogue he justified his ‘heretical’ acts as follows:

During the great “revision” of construction methods the mural became an inessential (and thus harmful) addition. The bare wall seems to be the definitive method for demarcating space of any kind. This approach has basically arisen from a superficial attitude towards painting, which apparently has no meaning and is thus pure decoration. But only the external aspect of painting is being evaluated here. In fact painting is not decoration, but a kind of tuning fork. Spaces that are created for some definite end, and whose usage is not of an ordinary kind, must have a special power, in order for people to internally “harmonise” with these spaces and be meaningfully influenced by them. And it is painting that has the appropriate means for this. But at the same time it does not need to be emphasised that ordinary living spaces do not go together with “stationary” painting: the essential qualities of such spaces are change and the possibility of variation.[45]

Concerning the reasons why he had used ceramic technology specifically for his ‘mural’, against all commonly held rules, Kandinsky remained silent. It should nonetheless be emphasised that his complex lining of the walls with ceramic tiles was an approach that to this day remains unique, especially for a private space.

The music room’s ceramic walls aroused great interest. Among foreign journals, the prestigious and exceptionally well-produced Italian journal La Casa Bella (The Beautiful Home), to take one example, devoted a stand-alone supplement to them.[46] At this time Kandinsky was, on the one hand, considered an important modern artist, and yet on the other hand he played a significant part, whether he wanted to or not, in the then-ongoing discussion within the ceramics industry, as led in particular by the painter and ceramicist Arthur Hennig, who was convinced that the same requirements should be applied to the decoration of mass-produced objects for everyday needs as to modern fine art. Kandinsky’s ceramic walls basically found themselves on the border between these two disciplines (fine and applied art). painting and ceramics. While photographs of the music room were reproduced in international reviews that came out at the time of the exhibition, in Czechoslovakia this did not happen until 1934, when it appeared on the cover of Bytová kultura (Housing Culture). This was not, for once, the result of typical Czech tardiness, but rather of financial problems faced by the magazine’s editors. The journal’s exceptional standard attests that in other circumstances the editors would have responded immediately.[47]

If Kupka’s unnoticed paintings A Tale of Pistils and Stamens (1919–1920) and Study for the Language of Verticals (1911) today deservedly belong to the important exhibits of the Prague National Gallery and the Thyssen-Bornemisz Museum in Madrid, interest in Kandinsky’s music room has inexplicably subsided. This is particularly evident when we observe the different degrees of attention these works have received from art-historical literature.

Translated by Jonathan OwenThese

Citations

[1] Hana Rousová, Abstrakce: Čechy mezi centry modernity 1918-1950: Nejen o vztazích volného a užitého umění (Prague: Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design in Prague (VŠUP)/Arbor vitae, 2015).

[2] Oleksandr Dovzhenko, Z deníků (Prague: Československý spisovatel, 1964), p. 82.

[3] Cited in Miroslav Lamač, Myšlenky moderních malířů (Prague: Odeon, 1968), p. 206.

[4] Paul Klee, ‘Z deníku 1914‘, in Paul Klee, Čáry (Prague: Odeon, 1990), p. 126.

[5] Sophie Lissitzky-Küppers and Jen Lissitzky (eds.), El Lissitzky, Proun und Wolkenbügel, Schriften, Briefe, Dokumente (Dresden: VEB Verlag der Kunst, 1977), p. 24.

[6] Cited in Lamač, Myšlenky moderních malířů, p. 138.

[7] Cited in Jerzy Płażewski, Filmová řeč (Prague: Orbis, 1967), p. 4.

[8] Viktor Shklovskii, Ejzenštejn, trans. Juraj Klaučo (Bratislava: Obzor, 1976), p. 189.

[9] Sergei Eisenstein, Kamerou, tužkou i perem, trans. Jiří Taufer (Prague: Orbis, 1961), p. 119.

[10] The book’s title arose from a discussion with Tomáš Jirsa. Thank you.

[11]Anthony Giddens, The Consequences of Modernity (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1990), pp. 5–6.

[12]Giddens, The Consequences of Modernity, pp. 18–19.

[13] Louis Cheronnet, ‘Quelques couvertures de livres Tschéco-Slovaques’, Art et Décoration (1929): pp. 113–116.

[14] Maximilien Vox, ‘Typographie’, Art et Décoration (1929): pp. 168–169. Cassandre, real name Adolphe Jean-Marie Mouron (1901–1968), was a Ukrainian painter living in Paris, where he became famous especially for his posters and his innovative typography. He created several influential typefaces and in 1929 his ‘Alphabet Double Bifur’ was published in the issue of Art et Décoration that 20 years later captivated Stanislav Remeš.

[15] The photograph was reproduced in 1927, as part of an advertisement for Josef Polák’s artistic workshop, in Publication du Conseil Municipal de Prague (Berlin: 1927), p. 316. Vojtěch Lahoda mentions it in ‘František Kupkaʼs Creation in Visual Art: “Organic” and Czech Connections’, Umění 44/1 (1996): p. 23, where he discusses it in relation to the smoking lounge’s furniture: ‘an interior with two top pictures Kupkaʼs making [a] perfect match with the rather extravagant pieces of late decorative Cubism’. Polak’s furniture company employed leading Cubist designers. Drawing on Rotislava Švácha’s expertise, Lahoda suggests that the furniture could have been the work of Josef Gočár or Josef Štěpánka. But this advertisement does not make it clear that the photograph was originally documenting the installation of the Czechoslovak pavilion in Paris in 1925.

[16] Hana Rousová, ‘Dekorace dekorativního umění’, in Lenka Bydžovská and Roman Prahl (eds.), V mužském mozku, Sborník k 70. narozeninám Petra Wittlicha (Prague: Scriptorium, 2002), pp. 89–95. This article did not change the situation: Kupka’s participation in the exhibition still went unmentioned in subsequent scholarly literature.

[17] For more detail about the opposing exhibition and the activities in the Czech lands that led up to it, see: Anna Pravdová, ‘V centru pařížského dění: Abstrakce 1924–1934’, in Hana Rousová (ed.), František Foltýn 1891–1976, Košice – Paříž – Brno (Brno: Moravská galerie v Brně, 2007).

[18] Respectively: Catalogue officiel de la section Tchécoslovaque. Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes (Prague: Comité d’exposition, 1925); Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes. Liste des recompenses (Paris: Hachette, 1925).

[19] Pavel Janák, ‘Výstava v Paříži, umělecký průmysl a život’, Výtvarná práce 4 (1926): pp. 207–233.

[20] In contrast to the other exhibitions, the Czechoslovak pavilion, which was literally stuffed with widely-criticised display cases, included very few paintings. I explain the reasons for this further on in this text. The photographic documentation shows that paintings were used only in several simulated interiors: besides Kupka’s paintings in the smoking lounge, Kremliček’s Washerwoman (Myčka, 1922) was hung above a bed in one bedroom, and one of Procházka’s post-Cubist still lifes was hung up elsewhere. It is probable that these paintings had been hastily borrowed from several private collections belonging to Czechs living in Paris, such as Václav Nebeský, author of the book L’Art moderne tchéchoslovaque 1905–1933 (Paris: Libraire Félix Alvan, 1937).

[21] Jindřich Toman, ‘František Kupka – Jindřich Waldes, z korespondence 1919–1936’, in Petr Meissner (ed.), Kupka – Waldes, Malíř a jeho sběratel, Dílo Františka Kupky ve sbírce Jindřicha Waldesa (Prague: Antikvariát Meissner, 1999).

[22] Toman, ‘František Kupka – Jindřich Waldes, z korespondence’, p. 110.

[23] Toman, ‘František Kupka – Jindřich Waldes, z korespondence’, p. 111.

[24] Jičínská later studied under André Lhote and Othon Friesz. I included several of her paintings in the exhibitions Czech Neoclassicism of the 1920s, Part Two: Between Classical Order and the Idyllic (Prague City Gallery, 1989), and Line, Colour, Form in Czech Visual Art of the 1930s (Prague City Gallery, 1988). In 2001 Barbora Zlámalová reworked her doctoral thesis on Jičínská into a monograph: Meziválečná tvorba malířky Věry Jičínské (Brno: Seminář dějin umění FF MU v Brně, 2002). Most recently, Jičínská’s work was presented at Martina Pachmanová’s exhibition From Prague All the Way to Buenos Aires: ‘Women’s Art’ and International Representation of Interwar Czechoslovakia (Galerie UM, Academy of Arts, Architecture, and Design Prague, 2014).

[25] Věra Jičínská, letter to Vladimír Maisner, 17 January 1924. Dobruška Museum (uncategorised).

[26] Jičínská, letter to Maisner, 17 January 1924.

[27] Toman, ‘František Kupka – Jindřich Waldes, z korespondence’, p. 112.

[28] Jičínská, letter to Maisner, 17 January 1924.

[29] Jičínská, letter to Maisner, 17 January 1924.

[30] Emanuel Siblík, ‘František Kupka’, Musaion 7 (1928): p. 9.

[31] Toman, ‘František Kupka – Jindřich Waldes, z korespondence’, p. 112.

[32] Instructions for the preparation of the exhibition can be found in Mezinárodní výstava moderních umění dekorativních a průmyslových v Paříži 1925 (Prague: 1925).

[33] Siblík, ‘František Kupka’, p. 32.

[34] Une Ambasade française. Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes Paris 1925 (Paris: Hachette, 1925).

[35] Zdeněk Macek, ‘Georges Fouquet’, Eva 2/1 (1 November 1929): p. 21.

[36] Jan Evangelista Koula, ‘Německá stavební výstava v Berlíně’, Eva 3/20 (1931): p. 25.

[37] All citations from: unnamed author, ‘Keramische Raumgestaltung’, Keramische Rundschau und Kunst-Keramik 39/32 (1931): p. 462. It is remarkable that this article, which remains interesting for several reasons, has not been mentioned in any of the scholarly literature dealing with Kandinsky, including that dealing with the music room. Most likely this is because the journal’s disciplinary focus falls outside the normal scope of art-historical research.

[38] Joseph August Lux, Die moderne Wohnung und ihre Ausstattung (Leipzig: Wiener Verlag, 1905), pp. 112–120.

[39] Lux, Die moderne Wohnung, p. 120.

[40] Jiří Kroha, ‘Umění v bytě’, Blok 1/8 (1946–1947): pp. 246–249. Citations taken from a reprint of the article in: Marcela Macharáčková (ed.), Jiří Kroha v proměnách umění 20. Století (Brno: Muzeum města Brna, 2007), p. 446.

[41] Johannes Martinus van Hardeveld, ‘Krása užitečnosti’, Bytová kultura, Sborník průmyslového umění 1/1 (1924–1925): p. 26.

[42] Unnamed author, ‘Keramische Raumgestaltung’, p. 462.

[43] Unnamed author, ‘Keramische Raumgestaltung’, p. 462.

[44] The information about the music room that appears in the scholarly literature is often extremely imprecise. For instance Annegret Hoberg, in her text on Kandinsky (published by the Guggenheim Museum in 2009 to coincide with a retrospective on the painter), mistakenly states on page 43 that the room belonged to a bachelor suite and was situated in the Radio Tower, one item in a small exhibition of Mies van der Rohe’s work that formed part of the German Building Exhibition. Tracey Bashkoff (ed.), Kandinsky (New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 2009).

[45] Vasilii Kandinsky, Deutsche Bauausstellung Berlin 1931, Amtlicher Katalog und Führer, exhibition catalogue, (Berlin: Bauwelt, 1931), p. 160.

[46] La Casa Bella 9/4 (1931): unpaginated.

[47] The journal Bytová kultura (Housing Culture) was published in Brno by Jan Vaněk, and the editorial board included Bohumír Markalous, Adolf Loos, and Ernst Wiesner. For financial reasons only two volumes were ever published, and between these there was a ten-year gap. The first appeared in 1924–1925, and the second in 1934–1935, but with only four issues.