By Mark Hallett, Märit Rausing Director

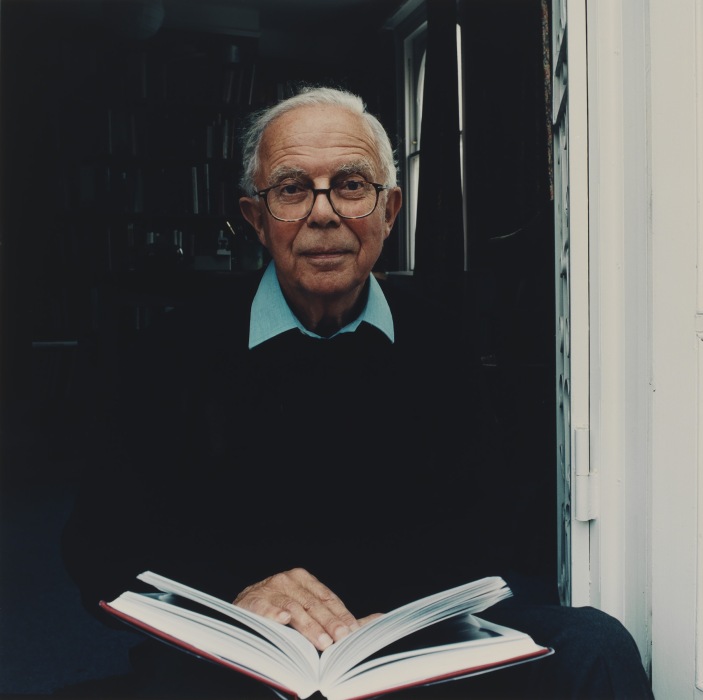

All of us at the Courtauld were deeply saddened to hear of the recent death of Sir Christopher White.

Christopher was a distinguished scholar and curator who also flourished as an institutional leader.

His art-historical interests were first honed in the early 1950s as an undergraduate at the Courtauld, which he remembered in his gentle but lively memoir, The Adventures of an Art Historian (2024), as a rather rarified institution:

“Although part of the University of London, the Courtauld stood apart as very much an elite organisation of its own, situated away from the main campus in an eighteenth-century house built by Robert Adam in Portman Square. One felt it was a privilege to be studying in such elegant, historic surroundings, with some major pictures on view. Paul Cezanne’s Card Players, for example, hung over Professor Anthony Blunt’s fireplace and Pieter Brueghel’s exquisite grisaille of Christ and the Woman taken in Adultery rested on a small stand on Professor Johannes Wilde’s desk.”

(How times have changed: today, of course, both pictures hang on public display and under tight security in our magnificent gallery. In his memoir, Christopher also went on to note of the Courtauld’s student body that “we were a small group, seven in my year, about twenty-one all told and about six graduates who were around the building regularly”. This year, the Courtauld’s student body numbers more than seven hundred).

Following his undergraduate years at the Courtauld, Christopher, always eager to explore new possibilities and to make the most of his prodigious talents and energy, went on to pursue an exceptionally varied career. He was, successively, an Assistant Keeper at the British Museum’s Department of Prints and Drawings, a director at P&D Colnaghi, and Curator of Graphic Arts at the National Gallery of Art in Washington. In 1973, he was appointed Director of Studies at the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies of British Art, where he fostered a close and enduring relationship with its partner institution, the Yale Center for British Art in New Haven. As someone who, at a later date, followed in Christopher’s footsteps as Director of the PMC, I can attest to the affection and respect he enjoyed on the part of all those associated with the Centre, where he was remembered as a consummate gentleman scholar who managed to inject a sense of both fun and possibility into everything he did.

In 1985, Christopher left the PMC to become the Director of the Ashmolean Museum, a role which he successfully held until his retirement in 1997. Thereafter, he maintained his prodigious yet seemingly effortless activity as a scholar, which had already encompassed a major study of Rembrandt’s etchings and the catalogue of the Dutch pictures in the Royal Collection, and which went on to include scholarly yet highly accessible monographs on Rembrandt, Rubens and Van Dyck. He was also in great demand as a Trustee and Board Member, at institutions such as the V&A, the Mauritshuis, and the National Art Collections Fund.

Throughout his life and career, Christopher maintained a close relationship with the Courtauld. He was awarded a PhD in 1970 for his research on Rembrandt’s etchings, and, as an Honorary Research Fellow, made a major contribution to the forthcoming catalogue of the Flemish Drawings at the Courtauld, which is due to be published in 2027. As in the case of everywhere he worked, Christopher was deeply appreciated by his Courtauld colleagues. In the words of my predecessor, Debby Swallow:

“Christopher brought together scholarly acuity, curatorial understanding, and a generosity to younger colleagues. Spending time with him was a real pleasure. Like many art historians, he loved the good things of life – good food, good wine and good conversation. An evening with Christopher and his lovely wife Rosemary – this year 100 years old – was always memorable for the mixture of wisdom and wickedness and laughter that they together created.”

Alongside his immense professional success and distinction – he was appointed a CVO in 1995, for services to his sovereign, and made a knight in 2001 – Christopher was defined by the modesty he exhibited in his personal life, and the grace he demonstrated to all those he met. Typically, he ended his memoir with a lovely, self-deprecating vignette of his twilight years in London:

“Weather permitting, Rosemary and I spend our afternoons mostly in the Rose Garden in Regent’s Park, where, to our amazement, we, an aged couple in their nineties, are frequently asked whether we would allow ourselves to be photographed, sitting side by side on a park bench. Minor though it may be, we clearly still have a role to play.”

Christopher will be much missed and long remembered, and we extend our deepest sympathies to Rosemary and their three children.