Throughout my first term as an undergraduate photography student at the Arts University Bournemouth, we were encouraged to put all digital technology away, to get in the darkroom, and to think about the very fundamentals of the medium: drawing with light. This was 2010, the same moment that the V&A presented the seminal exhibition Shadow Catchers, which celebrated camera-less photographs and alternative, analogue processes, including the work of Pierre Cordier, Susan Derges and Adam Fuss. From that moment, I was fascinated with the materiality of photography.

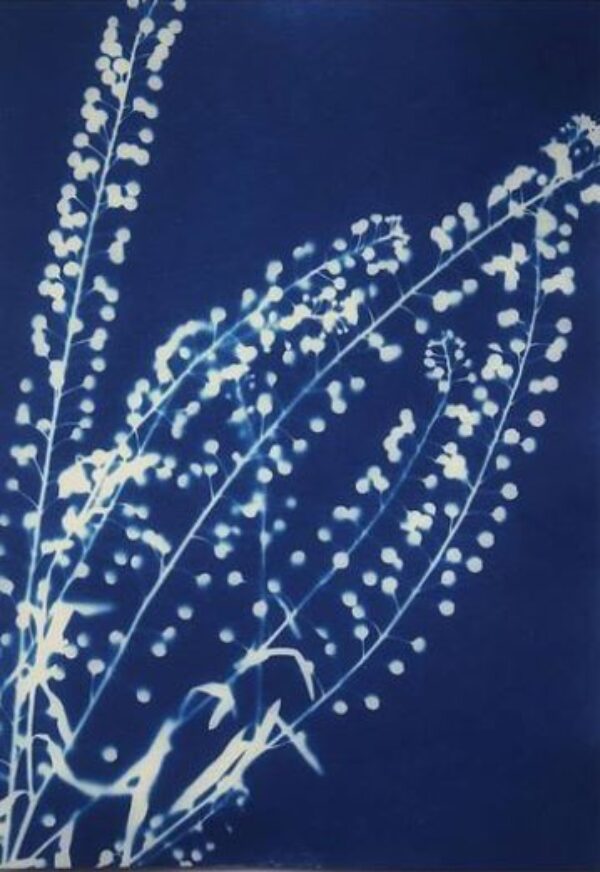

Just over ten years later (eek!) and I spend more time writing about 19th century photography, and trawling through photographic archives, than I do producing images. One of the small pleasures of the first lockdown was returning to making images, either on a daily walk or by creating simple cyanotype exposures in my garden with pre-treated paper, to find a creative outlet. After a year of uncertainty and cancelled research trips, it was inspiring to still be able to visit the studio of artist and researcher Melanie King, founder of the London Alternative Photography Collective, if only via Zoom, for her demonstration developing camera-less prints (or chemigrams) using Caffenol, as part of Material Witness.

I often feel conflicted about returning to the darkroom as the nostalgic smell of the darkroom’s chemicals act as a potent reminder of their harmful impact on the environment. Melanie, whose research is concerned with sustainable darkroom practices, showed us how it is possible to reduce this impact by replacing traditional photographic chemicals with everyday ingredients: Caffenol developer is a mixture of soda crystals, salt, vitamin c, water, and… coffee. The coffee can be substituted for any natural dye; think red cabbage, or peppermint tea!

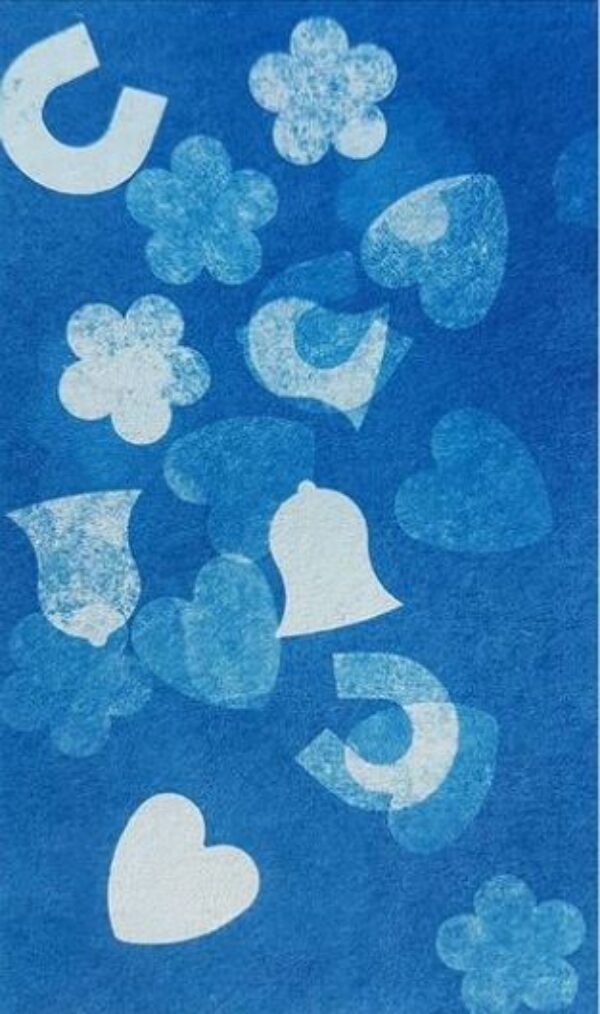

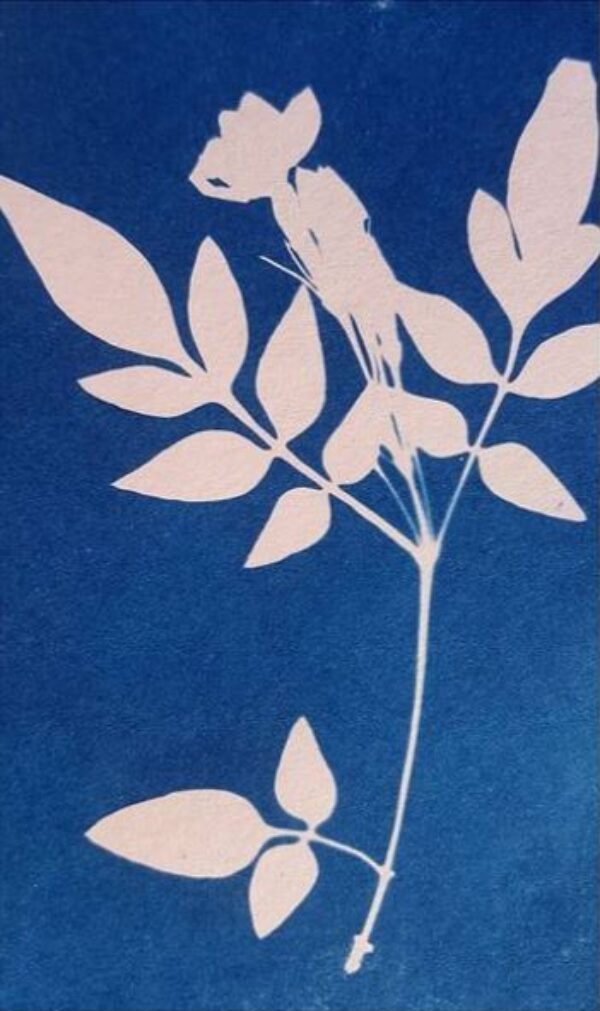

To create the prints shown, Melanie used stencils and brushes to apply developer and fixative directly to the photo paper, then washing them off after the desired affect was achieved. A photosensitive image will fade unless it is ‘fixed’. This can be done with salt water, but for archival permanence photo chemicals are required; to minimise the harmfulness they should be reused, exhausted and the silver oxides can be extracted with a piece of copper. However, Melanie provocatively questioned the need for the permanence of the image? Do we really need all images to last indefinitely?

With thanks to Melanie King for a fantastic Material Witness workshop!

For reading recommendations, please see the list provided by the London Alternative Photography Collectives’ Sustainable Darkroom programme: http://www.londonaltphoto.com/reccomended-reading

Image credits:

Caffenol Film Developing Demonstrations by Melanie King https://www.melaniek.co.uk/

Cyanotypes by Sarah French @sjfrenchie