#MaterialWitness 2019 got underway at Lambeth Palace Library with a group of CHASE students from the Universities of East Anglia, Kent, Sussex, SOAS, Birkbeck, The Courtauld Institute and The Open University.

Lambeth Palace Library is the historic library and record office of the Archbishops of Canterbury and the principal repository of the documentary history of the Church of England. Founded by Archbishop Bancroft, the records held there date from the 9th century to the present day. The medieval manuscripts number over 600, and include biblical texts, law books, liturgical and patristic collections, devotional works, saints’ lives, sermons, chronicles, cartularies and letters.

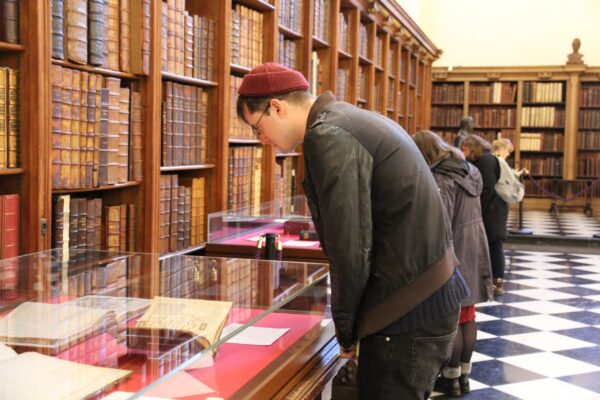

Our visit started in the Great Hall of Lambeth Palace where Assistant Archivist Alison Day gave us an overview of the history of the library and collection. We learned that the Great Hall has been built and re-built many times over the centuries. It was here that Erasmus and Holbein were welcomed by Archbishop Warham and where Henry VIII was entertained by Thomas Cranmer. The Parliamentarians ordered the demolition of the building following the English Civil War and it was not until the Restoration that Archbishop Juxon rebuilt it, attempting to replicate the original medieval style. In his diary of 1665 Samuel Pepys described a visit to see ‘Bishop Juxon’s new old-fashioned hall’.

Alison also told us about a pet tortoise owned by Archbishop William Laud. When journeying from Fulham Palace to Lambeth Palace, Laud had an unfortunate accident: ‘my coach, horses, and men sank to the bottom of the Thames in the ferry-boat’. Miraculously the tortoise survived this ducking and ended up outliving Laud too, who was imprisoned in the Tower of London and beheaded in 1645. The shell of the tortoise is still on display in the Palace!

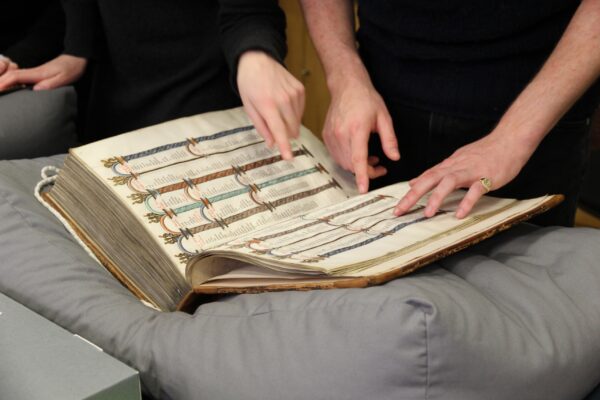

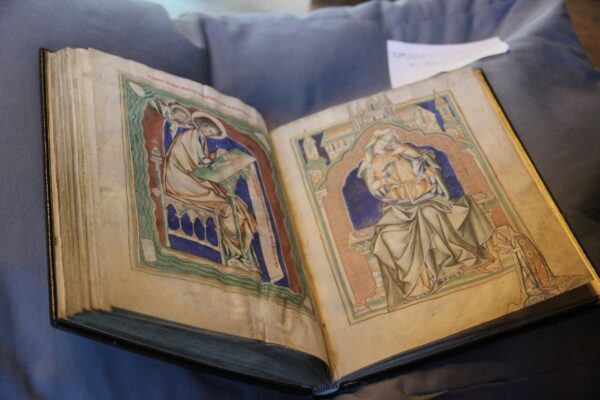

We then moved into the library reading room where a mouth-watering array of manuscripts were waiting for us. After advice on handling from Alison, the group was let loose and able to experience at first hand the materiality of these wonderful manuscripts. The oldest objects on display were two Greeks manuscripts dating from the 11th-12th centuries. Lambeth Palace MS 1176 was a gospel book with Eusebian canon tables from the monastery of the Holy Trinity, Chalke; it contained Evangelist portraits of Matthew, Mark and John together with a wonderfully vivid miniature of the Harrowing of Hell.

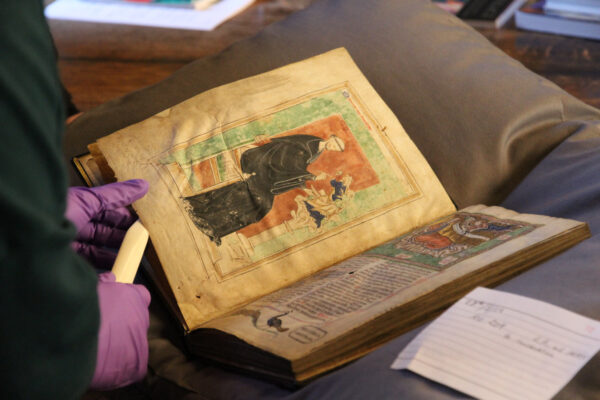

Other highlights included MS 496, a fifteenth-century Book of Hours made in Flanders for English use. Full of decoration and illumination, this prayer book also showed evidence of iconoclasm with saints’ heads scratched out. In many cases the scratches were very light, and we speculated whether this was due to reluctance on the part of the iconoclast to desecrate and deface the book. In our tour of the Great Hall we had learned that it was destroyed by an incendiary bomb during WW2. Many of the books were damaged and we saw a printed book which had been saved from the fire. Although blackened and badly singed, the flames had licked around the corners and margin of the book but left the body largely intact.

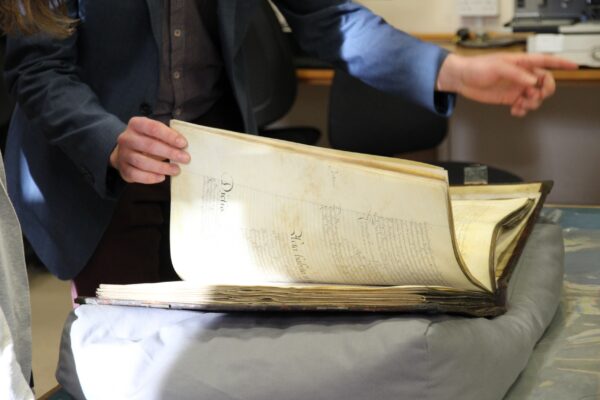

In the afternoon we moved to Morton’s Tower, the red-brick Tudor gatehouse and entrance to Lambeth Palace. Built by Cardinal John Morton in around 1490, it was here that Thomas More is thought to have lived when he joined the staff of Lambeth Palace at the age of twelve to gain an education in the workings of a prominent household. Morton’s Tower houses storage and work rooms for the conservation team at Lambeth Palace Library, including a book restoration centre, as well as offices and storage space for some of the libraries 230,000 books, texts and manuscripts. We continued to focus upon the materiality of objects under the expert guidance of Senior Conservator Lara Artemis. Lara has worked as a conservator-restorer in many of the leading collections in London including the British Library, the Wellcome Collection, the National Archives and the Houses of Parliament. We were also all fascinated to hear about the time she spent working at monastery of St Catherine at Mount Sinai.

Lara explained how we can learn about manuscripts through their materiality and chemistry, as well as by an understanding of history and provenance. She provided a fascinating overview of how manuscripts evolved from papyrus codices, such as those discovered in 1945 at Nag Hammadi, Egypt which date from the 3rd-4th centuries. Pliny describes some of the earliest uses of parchment and we learned about how it developed (via the Latin pergamenum and the French parchemin) from the name of the city of Pergamon, an important centre of parchment production in the Hellenistic period. The term ‘parchment’ originally referred only to the skin of cattle, sheep and goats. The equivalent material made from calfskin, which was of finer quality, was known as vellum (from the Old French velin or vellin, and the Latin vitulus, meaning a calf). We were able to handle samples of different types of parchment and vellum before hearing about the craft processes behind their manufacture.

We learned about different types of pigment which are generally divided into four groups: organic, inorganic, synthetic organic and synthetic inorganic. We were able to examine organic pigments (those of natural origin, animal or vegetable, and usually carbon compounds), such as Carmine (from cochineal), Indian Yellow (from the urine of cows that eat mango leaves) and Madder. These we compared with inorganic pigments, namely chemical compounds from chemical elements other than carbons, such as Green Earth, Venetian Red and Lapis Lazuli. We learned about the hazards of handling some of these minerals, notably Lead and Vermillion (Mercury Sulphide) which is highly toxic.

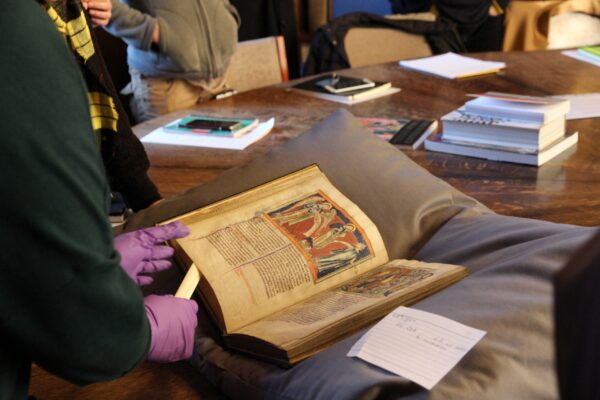

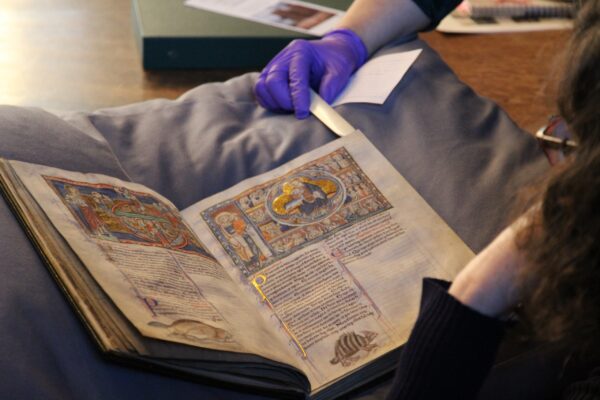

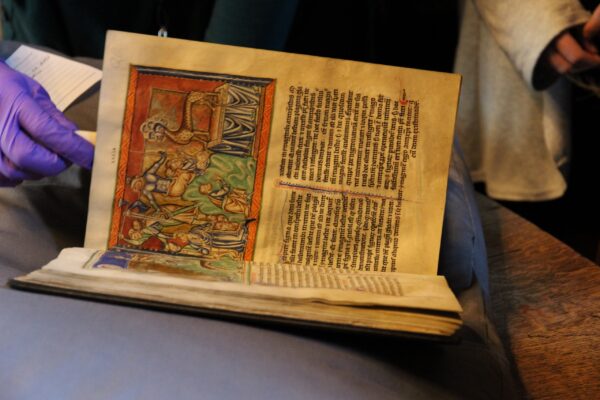

The highlight for the medievalists in the group was undoubtedly when Lara showed us Lambeth Apocalypse (MS 209), one of the treasures of the library collection. This deluxe vellum manuscript, containing the text of the St John’s Book of Revelation accompanied by the commentary of Berengaudus, was lavishly illustrated with events leading to the Last Judgement and the establishment of the New Jerusalem. We were able to identify some of the expensive pigments used by the artists, who were probably working in London in the mid-thirteenth century, such as Lapis Lazuli. We marvelled at the gold leaf which was used liberally throughout this manuscript and still glowed brightly in the afternoon light. Some of the marginalia, including a very fine beaver, peacock and porcupine, led to discussion of how this manuscript might have been viewed by its original owner.

With the Apocalypse safely stowed away, we rolled up our sleeves and had a go at mixing pigments and painting on parchment. We used ink made from oak gall and mixed pigments with egg white. There was even a small pot of Vermillion for those brave enough to try it! It was a brilliant end to a day full of close encounters with the materiality of manuscripts.

With thanks to the staff of Lambeth Palace Library.