Photography is mythologised as a morbid medium, carrying the trace of lost presences. Attending the Material Witness workshop on black and white photography, I was surprised to find its materials dynamic and unruly, prone to change in live time. The workshop provided an opportunity to become immersed in the mystic chemistry of the dark room, and to experience the marvel of seeing slippery silver take form as a photograph.

My research focuses on photography, dust and dirt, so I entered the workshop keen to advance my knowledge of the artform’s material processes. To date, my own efforts had consisted of thwarted trips to Snappy Snaps: tearing open my goody-bag of photos, only to find them interrupted by a portentous, blurry thumb. Thankfully our workshop leader Melanie King, artist and PhD candidate at the RCA, was on hand to help us avoid heart-breaking disasters, and to patiently guide us through each step of developing film and printing photographs.

Our first task was to take photographs around the bracing riverside location of North Greenwich. Thames-side Studios, where Gate Dark Room is based, hosts hundreds of artist studios within an intriguing industrial complex. Photogenic subjects around the site included a picturesque abandoned boat, seemingly grown into the river shingle, and the windows of artist studios around the estate, filled with paintbrushes, mannequins and objets d’art.

Back in the studio, Melanie took us through the basics of extracting the finished film from our cameras. The first step involved wrangling the film from its container, before winding it around a reel and putting it into a canister for processing. This was all done in the dark – the film and other materials were placed within sealed bags with sleeves for our hands to go through, so that we could retrieve the film without exposing it to light.

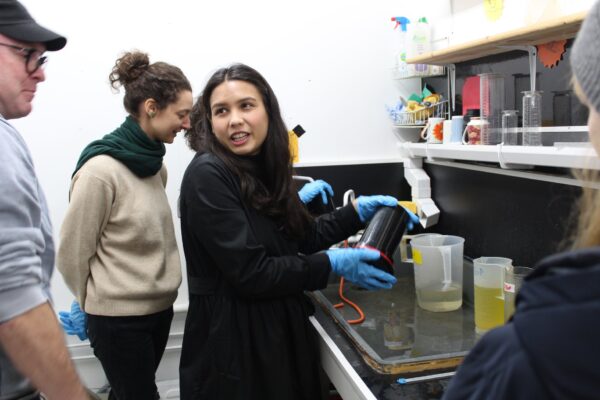

Next, we processed our films using developer, water and fixer, carefully measuring out each chemical component and bathing the film according to exacting timings. When the moment of truth arrived, some of our photographs refused to stay fixed, and a few of us were confronted with lolling tongues of imageless film, mysteriously pink: an example of the trial and error inherent to analogue processes. Luckily, there were plenty of negatives to go around, and those with the pink film found inventive ways of cutting and drawing into its surface.

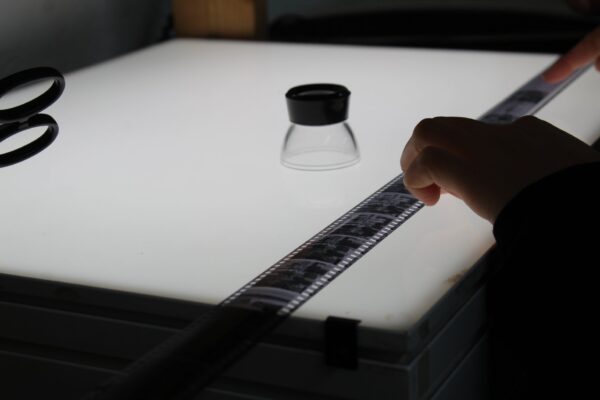

Once the negatives had dried, we made selections on which to develop, inspecting the miniature images on a lightbox. In the dark room, Melanie showed us how to do a ‘test’ print, enlarging the negatives and exposing them for differing lengths of time. Taking a seemingly blank sheet of photo paper and submerging it the next round of chemicals, I was thrilled to see an image blossom on its surface. It was easy to see how making photographs in this way, though painstaking, can be so rewarding and addictive.

The workshop provided a brilliant hands-on way to get to know the materials of photography, including information on more sustainable alternatives to the traditional chemicals used. Thank you to Alixe Bovey, Teresa Lane and the Material Witness organisers for providing an unbeatable opportunity to gain an increased understanding of analogue photography, which, for me, has sparked a renewed interest in taking photographs. As to whether or not it has cured my clumsy thumbs, I’ll have to wait for my next trip to Snappy Snaps.