This paper discusses the life of a bag that was produced by a Native American, came into the possession of Benjamin West by 1770, and was acquired by the British Museum in 1991. The paper’s primary focus is on the bag as evidence of Native American–European contact, which is made clear by its materials – many of European origin – and its style, seemingly influenced by European shoulder bags. I therefore seek to emphasise the persistence and adaptation of Native American material culture in the face of European colonisation, in line with the work of scholars like Ruth Phillips who have sought to give greater attention to objects that bear signs of cultural contact. In so doing, I draw upon Richard White’s conception of the ‘middle ground’, in which Native Americans were mutual (though not equal) participants in the process of forming European-Indigenous relations in North America through cultural negotiation and accommodation. In light of this, I argue that traditional understandings of West’s The Death of General Wolfe rely upon a faulty premise: its Mohawk warrior, though often read as a ‘noble savage’, is instead a figure that bears signs of Native Americans’ active negotiations with European presence in North America.

Chief among the many remarkable features of Benjamin West’s 1770 painting The Death of General Wolfe is his inclusion of a Mohawk warrior among the figures who look on in West’s dramatised depiction of Wolfe’s death in the 1759 Battle of Quebec, in which the British defeated the French in a turning point in the Seven Years’ War (Fig. 1).[1]

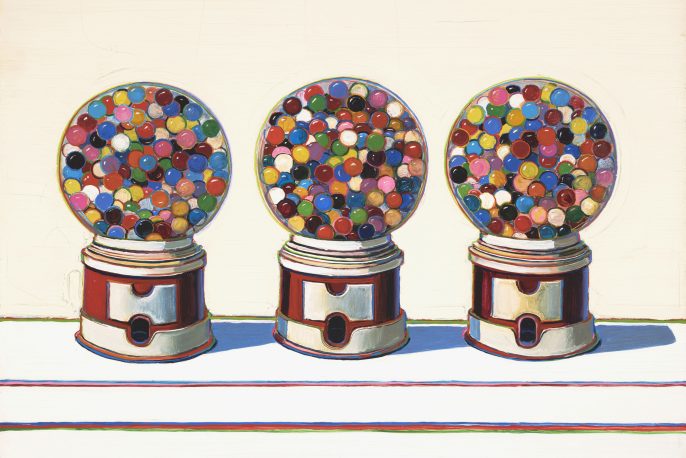

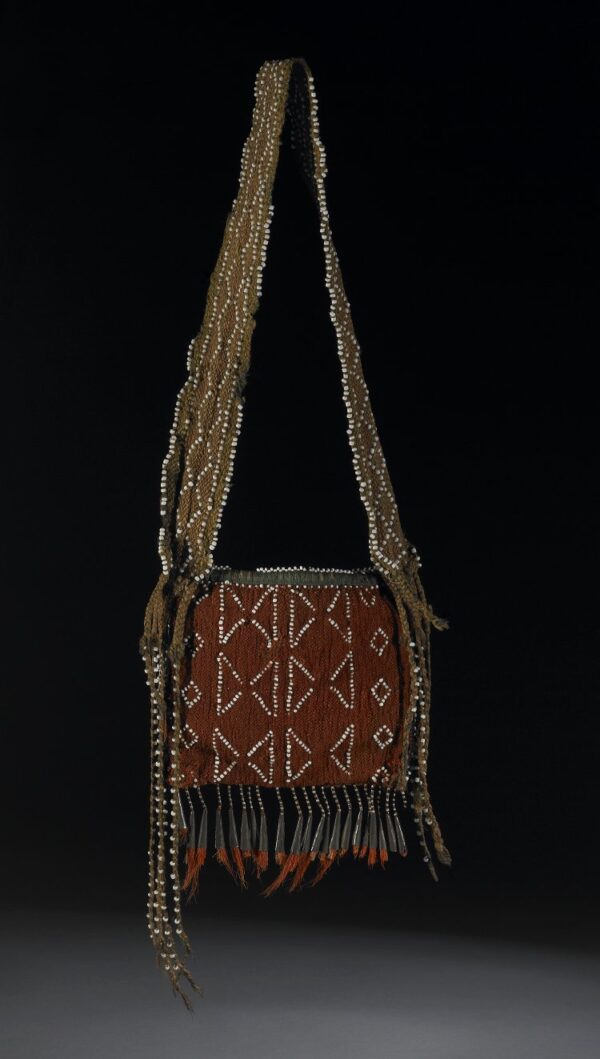

Native Americans participated in both sides of the war, but notably did not fight alongside the British at Quebec. West nevertheless included the Mohawk man, whom he depicts with what seems to be an almost-ethnographic level of detail and accuracy. The figure (along with the white ranger figure behind him), bears many accoutrements that proclaim his indigenousness to the viewer, among them a bag that is slung across his body and rests on his right hip. Today, we know that the perceived accuracy of the depiction of this bag is warranted, as West in fact owned the very bag – now in the collection of the British Museum – that his subject is wearing (Fig. 2). In comparing the real bag with its painted manifestation, the primary differences are that the bag is in fact significantly smaller than it appears, at 16.5 by 18 centimetres, and that its strap has been altered in appearance and lengthened. The real strap has a diamond pattern that appears to have been displaced onto the ranger’s bag, and is in fact only 70 centimetres long, making it effectively impossible for the bag to be worn cross-body. Beyond these differences, though, West’s painted depiction is strikingly faithful to its model. Notably, many of the material elements of the bag, like the metal, beads, and ribbon, are in fact European trade goods, revealing the bag to be a product of what Richard White calls the ‘middle ground’.[2]

As White argues, during the long-eighteenth century, Europeans and Native Americans (particularly in the Great Lakes region) engaged in a process of mutual invention and accommodation, creating a ‘place in between’ – the middle ground – in which ‘new systems of meaning and exchange’ developed.[3] It is important to avoid using the middle ground to idealise European-Native American contact, which ultimately resulted in literal and cultural genocide of Native American peoples by European colonisers.[4] The concept sits somewhat uncomfortably in our current moment of decoloniality, with some scholars critiquing the ways in which it can be used to gloss over the brutal realities of contact and colonisation, or the ways in which it overemphasises Native Americans’ adoption of European practices. [5] White’s framework of the middle ground, however, has been instrumental in reassessing our understanding of Native American cultural production, adaptation, and persistence during the long-eighteenth century, and in recognising the role Native American peoples played in the development of the North American colonies. Ultimately, though, their relative powers were far from equal. During the eighteenth century, Native American and European political, economic, and cultural activities were so closely intertwined that cross-cultural interaction, adaptation, and compromise characterised North American relationships for a period.[6]

Looking at Wolfe through the lens of the middle ground can allow us to see what Emily Ballew Neff recognises as the painting’s ‘underlying modernity’ as well as ‘West’s acuity in understanding the currents of global empire, British nationalism, and the importance of artistic and political diplomacy’.[7] Where Neff demonstrates that West was ‘the ultimate figure of the middle ground’, however, I am more interested in West’s Mohawk warrior, who is himself revealed to be a figure of the middle ground in my reading of Wolfe.[8] In light of White’s conception of the middle ground, examining the Mohawk warrior’s bag as an object – and particularly as evidence of cultural contact – is not only a worthy endeavour in itself but also raises new questions about The Death of General Wolfe and our understanding of the Mohawk warrior that West depicted within it.

A ‘NOBLE SAVAGE’?

Many scholars have discussed the Mohawk warrior, often in terms of European conceptions of the noble savage—reliant as it is on the figure’s seemingly precontact appearance—and the possibilities of North America and its continued colonisation. Vivian Green Fryd asserts that ‘West constructed the Indian as an innocent and noble savage, free from society’s encumbering practices and living in harmony with nature.’[9] She further argues that ‘the Native American symbolises the masculinity of an alien culture, that of the natural, uncivilised man.’[10] In David Solkin’s view, the figure’s (supposedly) ‘expressionless gaze serves to define an otherness which is both un-British and uncivilised’, in comparison to the emotive British figures and ‘sympathetic’ audience.[11] Jules Prown unequivocally asserts that the Mohawk warrior ‘appears as a noble savage’, and West seems to have intended for him to be read as such given his modelling of the figure’s pose on the Belvedere Torso and the figure’s largely naked body.[12] Such perpetuation of the noble savage stereotype, which suggests that indigenous peoples existed (especially prior to contact with Europeans) in a state of nature without the corruption of what Europeans deemed ‘civilisation,’ is not only harmful when considering its impact on indigenous peoples, but reductive in our consideration of depictions of indigenous figures such as the Mohawk warrior that West painted in Wolfe.[13] As Leslie Reinhardt has argued, art historians’ insistence on believing Native American figures are simply depicted as noble savages ‘flattens’ and even ‘nullifies the images’ and our understanding of them.[14] Scholars have also reduced the Mohawk warrior’s function to that of a symbol for the American continent or the many Native Americans who had participated in various conflicts over the last century.[15] Martin Myrone has described the figure ‘as an emblem of America… that is moved by noble sentiments and poignant sympathies to submit willingly to British authority.’[16] Other scholars who more actively resist the noble savage narrative have argued similarly: Stephanie Pratt argues that, despite his interest in ethnographic detail and accuracy, West reduces Native American figures to a ‘functional or attendant position’ in almost all of his depictions of them.[17] She writes that, like West’s other Native American figures, the Mohawk warrior is ‘positioned by West in a relationship to whites that contains his presence’, and that ‘the self-sufficiency of the Native American is replaced in these paintings by a position dependent on white culture.’[18] Douglas Fordham likewise calls the Mohawk warrior ‘simultaneously the most meticulously rendered and the most conventionally coded figure in the work’, who ‘serves to shift the painting into an allegorical register’ in his melancholy.[19] Fordham argues that the ethnographic detail of the painting serves to ‘[mark] an allegorical figure of America with traces of Woodland culture’, a reading that is supported by the fact that no Native Americans actually fought with the British at Quebec.[20] West’s inclusion of figures who were not present at Wolfe’s death (and his compression of the battle’s timeline) were essential features of his larger project to create an allegorical history painting of a contemporary event, and in a contemporary setting. Accomplishing this melding of the allegorical grand manner and contemporaneous details to apotheosise a national hero is what led contemporaries like Joshua Reynolds and later scholars like Edgar Wind to recognise the painting as revolutionary.[21]

When we prioritise interpreting Wolfe through the lens of its status as representing ‘The Revolution of History Painting’, as Wind put it, we risk losing the ability to recognise the more interesting aspects of West’s depiction of the Mohawk figure. Past scholars’ understandings of the Mohawk figure’s role in Wolfe are no doubt valuable, and it is likely that West intended for the Mohawk figure to function in the symbolic way they suggest. Nevertheless, by closely attending to the specific details of West’s depiction of the Mohawk warrior’s bag and the material realities of the actual bag which served as its model, I hope to offer a more nuanced understanding of the figure and his role in Wolfe. By reading Wolfe against the grain, we can destabilise conceptions of the Mohawk warrior as a noble savage or one who ‘submits willingly to British authority’, and instead see him as a figure who bears signs of Native American agency and negotiation in the face of colonisation on his person.

Much of Wolfe’s power comes from its depiction of this figure, whom West loads with both allegorical resonance and ethnographic detail.[22] As West’s friend Robert Bromley wrote in 1793, it is the inclusion of the Mohawk figure that marks the scene as one taking place in North America, as ‘the savage warrior shews [sic] us that the country was his’. The Mohawk figure not only denotes Wolfe as a North American scene; for Edgar Wind, the warrior acts as the ‘repoussoir’ that ‘[leads] the imagination to a distant land’.[23] It is the Mohawk warrior who gives Wolfe the sense of the ‘marvellous’ that a history painting needs, according to Wind – the figure is an element of the painting’s mirabilia.[24]

One reason that Wolfe’s audience may have found the Mohawk figure compelling is the level of seemingly accurate ethnographic detail that West included. Indeed, the authenticity of the warrior, for its audience at the 1771 Royal Academy exhibition, would have largely derived from the fact that he appears to exist in a state before Native American–European contact. This audience generally would have been more familiar with earlier depictions of ‘hybridised’ Native Americans—who incorporate recognisable elements of European garments into their dress—such as John Verelst’s 1710 portraits of the so-called ‘Four Indian Kings,’ and engravings of other Native Americans who came to London, such as the seven Cherokee ambassadors who met with King George II in 1730 (Fig. 3).[25] Aware of post-contact Native Americans, this seemingly unhybridised, precontact Mohawk warrior would have been all the more striking.

West’s depiction of the Mohawk warrior is in many ways, such as his unclothed torso and legs, unhistorical for a post-contact Mohawk figure. By the late-eighteenth century, most Iroquois people wore clothing that had been influenced by and incorporated European garments, such as cloth shirts and silver gorgets.[26] Reinhardt has discussed the symbolic power of such an idealised depiction of Native American dress in West’s 1776 portrait of Colonel Guy Johnson and Karonghyontye (Captain David Hill), arguing that West carefully combines accuracy and fantasy to capture the ‘complex authenticity’ of the Mohawk sitter.[27] Reinhardt thus adopts a contrarian position in relation to scholars like Fryd and Prown. She develops an understanding of West as an artist who uses the tension between European fantasies of Native Americans and the reality of contemporary indigenous dress and material culture to potently represent the complexity of Native American–European relations in the middle ground of late-eighteenth-century North America.

Such an understanding of West’s depictions of Native American figures can also be borne out in Wolfe. The figure, who has previously been understood as a primarily allegorical noble savage, in fact bears clear signs of the realities of Native American–European contact, most obviously in his shoulder bag. While bags have received detailed attention in studies of Native American material culture, this particular example and its biography leads to a fuller, and new, understanding of West’s The Death of General Wolfe. Close examination of the bag reveals Native American–European contact and exchange in both its materials and style: it is the type of object to which scholars such as Ruth Phillips have drawn attention for the ways in which they complicate our understanding of Native American cultural production and adaptation.[28] Further, centring the material history of the bag has the potential to change our perception of West’s The Death of General Wolfe, as the bag reveals that the intimate relationships between Native American and European are present not only in the hybridised ranger figure, but in the so-called ‘noble savage’ himself; even he is a man of the middle ground. West’s depiction of the Mohawk warrior therefore complicates typical readings of a fictionalised, pure, authentic Native American who belongs to the past; instead, his painted bag alludes to the potential agency of Native Americans who engage in material production, trade, and political activities in a cross-cultural manner.

THE BAG ITSELF

The body of the bag is nearly square, made of two pieces of flat, finger-woven wool, which are seamed at the bottom. The left and right sides have a strip of black woven wool where the front and back of the bag are joined. The front of the bag is resist-dyed into three horizontal stripes: two red with the undyed stripe in the centre. The back of the bag is solid red. (Fig. 4). White glass beads, slightly irregular in size and shape, are woven throughout the bag in geometric patterns: on the front, a central pair of vertical, mirrored zigzags, two vertical rows of four chevrons on either side, and a single zigzag on both vertical edges. The back of the bag features two vertical rows of three hourglass-like shapes. Five small diamonds follow the vertical edge of the bag on left and right. A green ribbon, presumably silk, is used to decorate the bag’s opening, with white beads sewn along its edges.

The bottom seam of the bag is decorated with twenty-two ‘tinkle-cones’ (one of which is partially missing) made up of a strand covered in alternating bands of black and white quillwork, from which hang tin cones filled with red-dyed deer or moose hair.[29] This fringing is repeated just above the undyed strip of the front of the bag, which features twelve tinkle-cones. The cones produce a light jingling sound when the bag is moved.

The bag’s strap is too short to be worn cross-body, but it could be worn on the shoulder or perhaps hanging from the neck.[30] The wool the strap is woven out of is almost khaki green in colour, with slightly greener wool making up each edge of the strap. Two vertical lines of beads run along each edge of the strap, and a diamond pattern runs along the centre. Both ends of the strap are sewn onto the top corners of the back of the bag. The strap is fringed at each end, with six wool braids on the left and five on the right, into which more white beads are woven. The braids hang past the ends of the tinkle-cones.

Though the decorative scheme of the bag is abstracted, it would have held significant symbolic resonance in Iroquois culture. The division of the front of the bag into three bands may be a reference to the spiritual zones of ‘sky, earth, and under-the-earth’.[31] Some bags feature representational thunderbird imagery, but scholars have argued that more abstract designs reference thunderbirds as well.[32] The thunderbird is a powerful guardian spirit for a wide range of Native American peoples, particularly the Iroquois, and is associated with war, storms, and protection against malevolent spirits.[33] It is often depicted with an hourglass-shaped body, and the hourglass-like triangles on the back of the bag appear to be a direct reference to this.[34] The zigzag lines that decorate the bag could then refer both to lightning, a typical attribute of the thunderbird, and to serpents, the malicious creatures from which thunderbirds offer protection.[35] Further, Ruth Phillips argues that even the chevrons and diamonds can be associated with thunderbirds and other spiritual beings, which Native Americans have understood to manifest themselves in more abstracted natural phenomena of light, sound, and weather.[36] The aural quality of the jingling tinkle-cones could also evoke the sound of thunder.

THE BAG’S RESURFACING

The bag’s existence as a tangible, three-dimensional object was all but unknown to the public until Jonathan King’s 1991 publication of ‘Woodlands Artifacts From the studio of Benjamin West 1738-1820’ in the American Indian Art Magazine. The article announced the British Museum’s acquisition of the bag and eleven other Native American artefacts that had once belonged to Benjamin West. The objects were brought to King’s attention when a man approached the British Museum for object identifications of the knife and sheath which, upon discussion with museum staff, was determined to be the knife depicted hung around the Mohawk warrior’s neck in Benjamin West’s The Death of General Wolfe.[37] West was, in fact, the man’s fourth-great-grandfather, and West’s collection of Native American objects had passed down through the family. Over time, however, much of their original history had been forgotten (or was at least overlooked), and the man initially suggested that the knife and sheath had been acquired by a nineteenth-century ancestor.[38] The objects were not treated with great care within the family: some of the objects – such as the now-lost pair of leggings the ranger in Wolfe wears – had been kept in a box of dress-up costumes.[39] The family likely disposed of the leggings along with other objects over the years, and it is difficult to determine the complete contents of West’s original Native American collection and their fate.[40] The relationship West’s descendants had with his Native American objects is perhaps unsurprising in terms of family heirlooms, but reflects the precarity of non-European artefacts that were collected in the west during the eighteenth century. During this period, and in a telling slippage of colonial and imperialist attitudes, practices of collecting non-western objects were less than systematic, with objects primarily ‘acquired as souvenirs and trophies’ in a manner more akin to collecting for cabinets of curiosity than for ethnographical or anthropological purposes.[41]

THE BAG’S HISTORICAL CONTEXT

It is largely due to eighteenth-century collectors rarely recording where their objects originated, or the identities of the groups that produced them, that the British Museum uses the broad categorisation of Northeast People to record the bag’s ethnic group of origin.[42] This categorisation also reflects the fact that, by the mid-eighteenth century, the material culture of Native American groups of the Northeastern Woodlands was becoming increasingly similar because of cultural blending, largely due to the disruptions of colonialism and warfare since European contact.[43] The geographic area of the Northeastern Woodlands encompasses numerous Native American groups (Fig. 5). King suggests the bag was likely produced by a member of the Iroquois Six Nations, and I follow that designation here for the sake of giving the bag some specificity.[44] The Iroquois are made up of the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca peoples, as well as the Tuscaroras, adopted refugees from North Carolina. Also referred to as the Haudenosaunee, their total population was around fifteen thousand during the eighteenth century.[45] It is difficult to say with certainty which group among the Iroquois would have made the bag, and even the attribution to the Iroquois remains in question given the interactions between Native American groups during the period. Iroquois or not, the person who produced the bag was almost certainly a woman, and the bag would have been intended for use by a man.[46] It is impossible to say for sure what this bag would have been used for – Native Americans have long used bags to hold items like medicine bundles, tobacco, or flint, and as European firearms were introduced, they also came to be used to carry shot.[47]

The bag, which likely came into Benjamin West’s possession at some point in the late 1760s, was probably made no earlier than 1750.[48] A limited number of similar bags exist in museum collections, but those that do are generally attributed to the second half of the eighteenth century. Despite longstanding Native traditions of bagmaking, bags of this style – a flat, squarish-body with a shoulder strap – seem to have only started appearing in the 1700s.[49] Scholars suggest this type of bag was inspired by Native Americans’ encounters with Europeans, who wore shoulder and cross-body (or bandolier) bags worn to carry ammunition and gunpowder (Fig. 6).[50] Earlier bag forms are admittedly limited in museum collections, but are more likely to take the form of pouches without straps, such as twined bags used as open containers more akin to baskets, or leather bags with drawstrings that may have been hung from the neck or tucked into belts.[51] The Northeastern Woodlands bag-with-strap that developed during the eighteenth century is a clear precursor to the bandolier bags that first developed around the Great Lakes in the nineteenth century, becoming increasingly elaborate and widespread over time.[52]

Cultural contact is evident not only in the bag’s style, but also in its material existence, as many elements of the bag – glass beads, wool from manufactured blankets, tin, and silk ribbon – are European trade goods.[53] One of the first indicators of the bag’s relation to European trade are the white glass beads woven throughout it. Beadwork has a long association with much Native American art, and some beads are produced from materials indigenous to North America. In the Eastern Woodlands, beads known as wampum were made from the shells of univalve whelks and quahog clams and were imbued with great symbolic importance.[54] Wampum was originally produced by Algonquian-speaking peoples of the New England coast and came to the Haudenosaunee via trade.[55] Modes of wampum manufacture also changed dramatically with the introduction of European metal tools, and eventually, European colonists started to produce great quantities of wampum themselves.[56] With the introduction of European-manufactured glass beads, wampum continued to hold its cultural significance, but was replaced by the cheaper glass beads in many goods.[57]

Glass beads were introduced to North America in the early stages of European contact. The Iroquois who lived near the Saint Lawrence River were likely introduced to beads by French explorer Thomas Aubert as early as 1508, and beads were certainly among the goods Jacques Cartier brought with him in 1534 while on an exploratory mission for the French crown.[58] Over time glass beads spread among Iroquois and other Native American groups, and they were frequently sewn or woven into items such as leggings, moccasins, sashes, and bags by the 1700s.[59] Though beadwork later became remarkably elaborate, during the eighteenth century most beadwork was restrained, taking the form of simple geometric patterns like in the case of this bag.

Another material of European origin is the metal, likely tin, tinkle-cones that are part of the bag’s fringing.[60] Metal usage became much more widespread with the introduction of European sheet metal: though recognised as fundamentally Native American, tinkle-cones became much more common after contact and can generally be understood as trade objects.[61] The green silk ribbon that edges the top of the bag would also have been a trade good brought over by Europeans.[62] The interior of the bag is lined with a simple tan fabric, probably European cotton trade cloth. Finally, the most prominent material of the bag – wool – is almost certainly of European origin.[63] Though wool was historically gathered from indigenous bison, by the mid-eighteenth century most wool used by the Iroquois (and other Native American groups) was European.[64] Furthermore, the wool used in the bag was almost certainly not made from ‘raw’ wool, but instead wool that was unravelled from a European-manufactured blanket (or other cloth). The practice of ravelling woollen blankets from Europeans into yarn that could then be used for Native American people’s own purposes was quite common by the eighteenth century; this wool was often used in combination with native fibres.[65]

All of this demonstrates the ways in which Native Americans incorporated European trade goods into their practices of material culture, suggesting that taking the painting at face value and reading the Mohawk figure as a purely allegorical noble savage gives us an impoverished understanding of the world in which Wolfe was painted. It is very possible that West and his contemporary viewers may not have had interest in, or recognised, the incorporation of trade goods sourced from the European continent in the bag. Indeed, as Fordham has argued, West likely included the bag simply to display his ‘representational command over ethnographic difference’ in his depiction of an otherwise largely allegorical figure, rather than out of any real interest in the complexities of Native American–European cultural exchange.[66] Nevertheless, our understanding of the hybridity of the bag destabilises the idea that the Mohawk warrior represents a noble savage, and instead denotes him as a figure of the middle ground, actively engaged with contemporary material culture and intercultural contact.

THE BAG’S JOURNEY

The bag is, of course, evidence of Native American–European contact not only in its material and stylistic qualities, but in the fact that it ended up in Benjamin West’s hands. Unfortunately, we lack evidence for how the bag made its way from its production by a Native American woman in North America across the Atlantic and into West’s London studio. There are many possible avenues for this movement, as West maintained an extensive transatlantic network.[67] Jonathan King suggests Sir William Johnson, Britain’s Superintendent of Indian Affairs from 1756 to 1774 as a probable source, given his close relations and extensive trade with Native American communities, and the fact that the powder horn depicted in Wolfe is inscribed with Johnson’s house and name.[68] Johnson’s house was such an important location, though, that it was depicted on numerous cartographic powder horns of the period, so this is far from conclusive.[69] Aside from West’s prominent contacts like Johnson, it is quite possible the bag could have been collected by an unknown British soldier, as they were avid collectors of Native American objects as souvenirs of their experiences in North America.[70]

It is unclear whether this bag is something that would have been intended for Native American use and later acquired by a person of European descent, or if it was always intended for European consumption. This is near impossible to conclusively establish, but David Penney has argued that while it is tempting to view shoulder bags as a new form of material culture for Native American use, ‘it is far more likely that they are the products of a relatively modest number of skilled artists whose work was accessible for purchase near the major centers of Native and European interaction, such as Niagara, Detroit, and Mackinac.’[71] Regardless of the status of this particular bag, it was produced at the beginning of the period of what, following Ruth Phillips, we can call the ‘self-commoditization’ of Native Americanness.[72] Beginning in the eighteenth century, and especially in the nineteenth, the pressures of the rapidly growing population of European colonists led many Native American groups to increasingly turn to producing commodities for European consumption.[73] While producing goods that incorporated many European-manufactured materials, Native American craftswomen began to consider what would be marketable to European colonists who wanted souvenirs of their North American experiences, and this marketability relied on making sure their objects seemed ‘authentic’.[74]

Perhaps ironically, these objects would later be seen as not authentic enough to be the subject of serious study of ethnographers, anthropologists, or art historians throughout the nineteenth and for most of the twentieth century. Relying on essentialist premises that denied the agency of non-western cultures, scholars historically rejected the study of objects that revealed European-Native American contact in favour of objects that seemed ‘pure’ (in Phillips’s terms) of European or otherwise colonial influence, and from a ‘mythic precontact past’.[75] More contemporary scholarship, however, has made clear that post-contact objects should not be viewed as evidence of a degradation of traditional Native culture, but instead as a reshaping of cultural practices in which new forms of creativity flourished.[76] This new scholarly paradigm, while aware of the power imbalance that tilted in favour of European colonialism, recognises the indigenous population as participatory agents who shaped European contact.[77]

THE BAG IN THE MIDDLE GROUND

Benjamin West was an avid collector, assembling a collection of some seven thousand objects over his lifetime.[78] His Native American objects – which he would have regarded as curiosities – once resided among his plaster casts and paintings, prints, and drawings by Old Masters and his contemporaries.[79] West carefully curated the display of his objects and they would have been seen by many visitors.[80] The artist’s collection and his display of them served in large part, as Kaylin Weber argues, to establish and attest to West’s ‘authoritative position’ as a history painter, giving his paintings (and himself and his studio) ‘deeper meaning and history’.[81] In Wolfe, the bag and other Native American objects work as reality effects, giving West’s seemingly allegorical Mohawk warrior the sheen of ethnographic accuracy to heighten the artist’s reputation as a painter with a unique understanding of North America.[82] West’s ownership of Native American objects and his depiction of them in Wolfe and other paintings serves as his truth claim, which asserts that because West has accurately recorded these objects of a faraway people, the historical truth of the rest of his painting can, supposedly, be relied upon too.[83] When Edgar Wind called such faraway marvels mirabilia, he argued that much of West’s success as a contemporary history painter lay in his production of an exotic distance, the efficacy of which increased with this accuracy.[84] Scholars’ understanding of the Mohawk warrior as a ‘noble savage’ apparently untouched by western civilisation would, perhaps, have been the ultimate sign of mirabilia for an eighteenth-century London audience.

The truth that the Mohawk warrior is wearing a bag styled after European models and made of European materials complicates this understanding. Previous scholars who have noted the detailed accuracy of the bag and other Native American objects in Wolfe have sought to incorporate this into analyses of the painting that continue to view the Mohawk figure as a noble savage who acts as an attendant figure to the central drama of Wolfe.[85] This ultimately contributes to a broader understanding that the painting’s Mohawk figure represents a people soon to be overtaken by European colonialism. Regardless of whether this is how West intended the figure to be read, by attending to the material realities of the bag we can instead see the figure West painted as one who represents the ways in which the Iroquois navigated the cross-cultural relations of Native American–European contact, while still appealing to the audience’s desire to see mirabilia in history painting. It is these very signs of contact that mark this bag as an authentic Native American object of the eighteenth century, a product of cultural creativity and resilience in the face of increasing European presence and pressure.

Citations

[1] Much has been made of Benjamin West’s apparent affinity for Native Americans, and especially Mohawks. This is demonstrated by the possibly apocryphal story of West likening the Apollo Belvedere to a Mohawk warrior, and the certainly apocryphal recounting of him learning to prepare colours from Native Americans. John Galt, The Life and Works of Benjamin West, Esq.: President of the Royal Academy of London, (London: T. Cadell and W. Davies, Strand, 1820), vol. 1: 105 and vol. 2: 17–18. It is unlikely West actually had close encounters with Native Americans as a boy in Pennsylvania – see Susan Rather, The American School: Artists and Status in the Late Colonial and Early National Era (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016), 93.

[2] Richard White, The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650–1815 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991).

[3] White, x.

[4] Scholars’ estimates of the native population of North America prior to 1492 vary widely – a conservative range is one–eight million before contact. The census data of the United States and Canada indicate a native population of only four hundred thousand by the beginning of the twentieth century. See Russel Thornton, ‘Population: Precontact to the Present’, Encyclopedia of North American Indians (last accessed 2 August 2022, archived at Wayback Machine, https://web.archive.org/web/20060208053232/http://college.hmco.com/history/readerscomp/naind/html/na_030500_precontactto.htm).

[5] See articles included in ‘Forum: The Middle Ground Revisited’, The William and Mary Quarterly 63, no. 1 (2006): 3–96 (last accessed 2 August 2022, https://www.jstor.org/stable/i278777).

[6] White, ix–xv.

[7] Emily Ballew Neff, ‘At the Wood’s Edge: Benjamin West’s “The Death of Wolfe” and the Middle Ground’, in Emily Ballew Neff and Kaylin H. Weber (eds), American Adversaries: West and Copley in a Transatlantic World (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014), 68, 98.

[8] Ibid., 68.

[9] Vivien Green Fryd, ‘Rereading the Indian in Benjamin West’s “Death of General Wolfe”’, American Art 9, no. 1 (1995): 80.

[10] Fryd, 83–84.

[11] David H. Solkin, Painting for Money: The Visual Arts and the Public Sphere in Eighteenth-Century England (New Haven: Yale University Press for the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, 2005), 211–212.

[12] Jules David Prown, ‘Benjamin West and the Use of Antiquity’, American Art 10, no. 2 (Summer 1996): 41.

[13] Ter Ellingson, The Myth of the Noble Savage (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001).

[14] Leslie Reinhardt, ‘British and Indian Identities in a Picture by Benjamin West’, Eighteenth-Century Studies 31, no. 3 (1998): 283 (last accessed 14 July 2022, www.jstor.org/stable/30053664).

[15] Ann Uhry Abrams, The Valiant Hero: Benjamin West and Grand-Style History Painting (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1985), 176; Stephanie Pratt, The European Perception of the Native American, 1750–1850 (PhD Dissertation, University of Exeter, 1989), 191.

[16] Martin Myrone, Bodybuilding: Reforming Masculinities in British Art 1750–1810 (New Haven: Yale University Press for the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, 2005), 110.

[17] Pratt (1989), 193.

[18] Pratt (1989), 195–196.

[19] Douglas Fordham, British Art and the Seven Years’ War: Allegiance and Autonomy (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010), 235.

[20] Fordham, 235–236.

[21] Edgar Wind, ‘The Revolution of History Painting’, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 2, no. 2 (October 1938): 116; Uhry Abrams, 180; Solkin, 211–212; Robert C. Alberts, Benjamin West: A Biography (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1978), 107–109.

[22] Ibid., 235–236.

[23] Wind, 117–119.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Kevin R. Muller, ‘Pelts and Power, Mohawks and Myth: Benjamin West’s Portrait of Guy Johnson,’ Winterthur Portfolio 40, no. 1 (2005): 47–76, www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/500154; Stephanie Pratt, ‘Reynolds’ “King of the Cherokees” and Other Mistaken Identities in the Portraiture of Native American Delegations, 1710–1762,’ Oxford Art Journal 21, no. 2 (1998): 135–50, www.jstor.org/stable/1360618.

[26] Reinhardt, 292.

[27] Reinhardt, 296–297.

[28] Ruth B. Phillips, ‘Reading and Writing between the Lines: Soldiers, Curiosities, and Indigenous Art Histories’, Winterthur Portfolio 45, no. 2/3 (2011): 107–124 (last accessed 14 July 2022, www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/661560).

[29] Karlis Karklins, Trade Ornament Usage Among the Native Peoples of Canada: A Source Book (Ottawa: Minister of Supply and Services Canada, 1992), 24. Moose hair was suggested by Cynthia McGowan (assistant collections manager at the British Museum) in conversation with the author and Catherine Doucette (20 November 2019).

[30] John Warnock, Marva Warnock, and Clinton Nagy (eds), Splendid Heritage: Perspectives on American Indian Arts (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2009), 68.

[31] Pieter Hovens and Bruce Bernstein (eds), North American Indian Art: Masterpieces and Museum Collections in the Netherlands (Aldenstadt: ZKF Publishers, 2015), 110.

[32] Ruth B. Phillips, ‘Dreams and Designs: Iconographic Problems in Great Lakes Twined Bags’, in David W. Penney (ed.), Great Lakes Indian Art (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1989), 53–68; Edward J. Lenik, ‘The Thunderbird Motif in Northeastern Indian Art’, Archaeology of Eastern North America 40 (2012): 163–185 (last accessed 14 July 2022, www.jstor.org/stable/23265141).

[33] Phillips (1989), 56.

[34] Ibid., 56.

[35] Lenik, 164, 182.

[36] Phillips (1989), 62.

[37] Jonathan C. H. King in correspondence with the author and Catherine Doucette (7–16 November 2019).

[38] King (7–16 November 2019).

[39] Ibid.

[40] J. C. H. King, ‘Woodlands Artifacts From the studio of Benjamin West 1738–1820’, American Indian Art Magazine, 17, no. 1 (Winter 1991): 46.

[41] J. C. H. King, First Peoples, First Contacts: Native Peoples of North America (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999), 8.

[42] King (1999), 67.

[43] See Ruth B. Phillips and Dale Indiens, ‘“A Casket of Savage Curiosities”: Eighteenth-century objects from north-eastern North American in the Farquharson collection’, Journal of the History of Collections 6, no. 1 (1994): 24.

[44] King (1991), 39.

[45] Richard Aquila, The Iroquois Restoration: Iroquois Diplomacy on the Colonial Frontier, 1701–1754 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1997), 30.

[46] Janet Catherine Berlo, ‘Men of the Middle Ground: The Visual Culture of Native-White Diplomacy in Eighteenth-Century North America’, in Neff and Weber (eds), 111.

[47] Kate C. Duncan, ‘So Many Bags, so Little Known: Reconstructing the Patterns of Evolution and Distribution of Two Algonquian Bag Forms’, Arctic Anthropology 28, no. 1 (1991): 56 (last accessed 14 July 2022, www.jstor.org/stable/40316292).

[48] King (1991), 40.

[49] David W. Penney, North American Indian Art (London: Thames & Hudson, 2004), 60–61.

[50] Ralph T. Coe, The Responsive Eye: Ralph T. Coe and the Collecting of American Indian Art (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003), 204; Hovens and Bernstein (eds), 118; Ruth B. Phillips, ‘Like a Star I Shine: Northern Woodlands Artistic Traditions’, in The Spirit Sings: Artistic Traditions of Canada’s First Peoples (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1987), 83–85.

[51] Duncan, ‘So Many Bags, so Little Known: Reconstructing the Patterns of Evolution and Distribution of Two Algonquian Bag Forms’, 56–66.

[52] Andrew Hunter Whiteford, ‘The Origins of Great Lakes Bandolier Bags’, American Indian Art Magazine 11, no. 3 (1986): 32–43.

[53] Christopher L. Miller and George R. Hamell, ‘A New Perspective on Indian-White Contact: Cultural Symbols and Colonial Trade’, The Journal of American History 73, no. 2 (1986): 311–328 (last accessed 14 July 2022, https://www.jstor.org/stable/1908224).

[54] King (1999), 49.

[55] Gail D. MacLeitch, Imperial Entanglements: Iroquois Change and Persistence on the Frontiers of Empire (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011), 18; King (1999), 49.

[56] Berlo, 110.

[57] King (1999), 47–49.

[58] Karklins, 93.

[59] Ibid.

[60] McGowan (20 November 2019).

[61] Karklins, 75, 93.

[62] Rita J. Adrosko, ‘A “Little Book of Samples”: Evidence of Textiles Traded to the American Indians’, in Textiles in Trade: Proceedings of the Textile Society of America Biennial Symposium, September 14–16, 1990 (Washington, DC: Textile Society of America, 1990), 65–74.

[63] Christian F. Feest, Native Arts of North America (London: Thames and Hudson, 1980), 123.

[64] Hovens and Bernstein (eds), 104.

[65] Feest, 123.

[66] Fordham, 235–236.

[67] Kaylin H. Weber, ‘A Temple of History Painting: West’s Newman Street Studio and Art Collection’, in Neff and Weber (eds), 38; King (1991), 42–44.

[68] King (1991), 44–45.

[69] Berlo, 110.

[70] Ruth B. Phillips, Trading Identities: The Souvenir in Native North American Art from the Northeast, 1700–1900 (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1999), 25.

[71] Penney, North American Indian Art, 60–61.

[72] Phillips (1999), 4.

[73] Ibid., 4.

[74] Ibid., 9.

[75] Phillips (1999), 7.

[76] MacLeitch, 4–5.

[77] Ibid., 1–11.

[78] Weber, 26.

[79] Ibid., 23, 26, 43.

[80] Ibid., 14–15.

[81] Ibid., 23.

[82] Roland Barthes, ‘The Reality Effect’, in The Rustle of Language, 1969, Richard Howard (trans.), François Wahl (ed.) (Berkley: University of California Press, 1989), 141–148; Fordham, 235–236.

[83] See Linda Nochlin’s discussion of the reality effect in Orientalist paintings in Linda Nochlin, ‘The Imaginary Orient’, Art in America (May 1983): 122–123.

[84] Wind, 116–121, 126.

[85] Pratt (1989), 193–195; Fordham, 235–236.