Dr Emma Richardson spent her childhood sliding down the parquet corridors of the University of Sheffield’s Materials Science department in her socks and scaling the stairs of Scunthorpe’s blast furnaces behind her father, a materials scientist. Richardson is now, via art conservation, a materials scientist, too: a preservation scientist working on polymers in heritage collections. She was Head of the Material Studies Laboratory in the History of Art department at UCL until 2019, and is now Director of Research at Rochester Institute of Technology’s Image Permanence Institute in New York. Richardson joined Editor-in-Chief Alice Dodds from her laboratory to discuss the complex science behind softness and how artworks might be affected by the strange lives of their soft materials.

Let us start with the big question: what is it that makes material soft?

It is a big question. It is to do with the underlying chemical structure and also the physical structure of the materials, really, so there are a few things at play. There’s the molecular level—the micro level—and then the bigger macro levels of materials that influence softness. It’s complicated. From a chemical perspective, it’s really to do with how the atoms and molecules interact with each other in a material, how closely they pack together, how many there are, et cetera. What are those interactions and how strong are they? Is there just one component or multiple components? The physical—more macro level—aspect can have an impact on whether materials are soft or malleable too. Think about the physical nature of a textile or fibres: some of the crimp in the textiles or twist in the actual fibres themselves allow for the material to be manipulated and moved around. Ultimately, it’s complicated.

I suppose ‘soft’ is not easy to define—it encompasses many different chemical or physical properties.

I think the word soft is a good descriptor, but it can be used to encompass a number of different materials and that have different types of properties.

For materials we might talk more about whether a material is brittle or ductile or malleable. Brittle materials are quite rigid and they will break readily without a lot of deformation in the material before they fracture. Whereas ‘softer’ materials—things that are ductile and malleable—you can apply some force to them and their shapes will move and deform.

You might think of soft materials as being responsive to a force and readily deforming with that force. Sometimes materials deform elastically so that you can apply a force, release the force, and then the materials will come back to their original dimensions and shapes. Or you might have something called plastic deformation, which is a permanent change. You apply a force, and if you apply enough force they permanently move and deform into a new shape.

Whether plastic or elastic, softness does—from what you’ve said—seem to depend on deformation. Does this have implications for how objects made from these soft, deforming materials age?

Certainly. A lot of materials that originate as being soft—organic materials such as fibres or paper or parchment—have moisture in them. They can be plasticised, they can be malleable, and over time some of the properties of those materials can change due to chemical interactions. On exposure to light, high humidity, and so forth, you can get reactions that occur that cause what are essentially flexible polymer chains to start to link up. Neighbouring chains enable some degree of movement and malleability, but as they start to react, those chains can start to link with one another, and they form something called cross-links between the chains. That’s when you start to get materials like adhesives that were once flexible becoming quite brittle.

We’re currently working on parchment and that has been really interesting. It is a really soft material that, when degraded, can either be very brittle, like crackling, or it can be gelatinous and a bit disgusting—it’s a material that is able to take on a number of different forms.

So, materials can move from soft to hard, but sometimes you end up with the opposite happening—in some cases they become softer. Think about the canvas on a stretcher over time. There is some tension on that intentionally to create a surface onto which you can paint, but over time you find that stress relaxation occurs, and the fibres start to move, resulting in a softening of what was once a fairly taut material.

So are all soft sculptures going to become floppy, like old teddy bears?

I wouldn’t like to say yes or no—don’t lead me down that route!—but I think certainly there is the opportunity for those stresses to relax and you may see changes. You may lose some of that structure. Equally, your soft sculptures may become rigid with time.

The issue of works becoming softer, almost oddly gelatinous, is disgustingly fascinating. You mentioned that environmental conditions, for instance light and humidity, have an effect on materials becoming more brittle. What are the conditions that might make an object turn soft?

A lot of the things we think about in terms of physical properties are dependent on temperature and, in a lot of cases, moisture—but not all cases.

Certain materials will go through a melting temperature; if you hit high enough temperatures, they will melt. At melting temperature, you go from a very clear-cut solid to a liquid. That’s a very defined phase change that happens. You see that in metals: it can very quickly cross over at very defined temperatures. Other materials will just disintegrate; they will degrade at a critical temperature. Before you reach those high temperatures, which we are unlikely to reach within collecting institutions, certain materials will pass through something called a glass transition temperature. They go from a glassy rigid material to this more pliable rubbery material. The glass transition temperature is not a defined temperature—it occurs over a range of temperatures. Things start to become softer and more viscous as they move into this range, and they can become more pliable. Materials like thermoplastics or glasses transition through this middle space.

The glass transition temperature is quite important in terms of this idea of softening points and soft materials. The transition can occur below freezing, so by the time you’re working with materials at room temperature, they are already pliable—they have already passed through that softening temperature.

The glass transitions depend very much on the chemistry. Moisture acts as a plasticiser for polymer materials: it pushes the glass transition temperature down to lower temperatures by enabling the molecules to push apart and those molecules can start to move around more readily. Think, for example, about your hair: when you wash your hair moisture penetrates the hair fibres, and it allows a greater manoeuvrability of the helix in the keratin. The same thing happens in other polymers when the moisture penetrates the structure: it will cause the polymer to become plasticised.

Is there a material used in artworks that you find particularly susceptible to these changes?

Beeswax would be a prime example. The softening temperature of beeswax is around Let’s say you are transporting an object that has beeswax and it sits on the tarmac at an airport, reaching around forty five degrees centigrade due to the thermal gain from the sun. The wax is not going to melt into a pool of liquid—you are not going through its melting temperature—but it is somewhat more pliable. Depending on whether it is being used in isolation or in combination with another material that is heavier than the wax an inducing a force, there is a potential for change.

These types of factors play into our thinking in terms of managing collection environments. If wax were to be in an uncontrolled environment, it may well be that particulates would have a greater affinity to sticking to the surface because the surface has become softer, become more receptive to that infiltration. In terms of collections care, we need to think about managing environments locally for those particular needs, rather than treating an entire collection as though it’s vulnerable to these changes. Not all objects are vulnerable to moderate changes in their environment.

Temperature is important, because whether a material is soft or not depends on what temperature ranges you are working at. Plasticized PVC will become very brittle if you lower the temperature below its glass transition temperature. Polyurethane foams—things we inherently see as malleable as we can squeeze them and they bounce back—if you put them in liquid nitrogen they’re going to be brittle and could be smashed with a hammer. These materials are soft at ambient temperatures but are not necessarily soft if they are being worked at a different temperature range.

That complicated relationship between hardening and softening, chemical and physical must cause problems for how we go about conserving or preserving these kinds of materials in collections, or for instance transporting the for exhibition.

Absolutelymonitored thirty-two crates as they travelled around the globe during different seasons in truck transit and air freight. We monitored the environmental conditions inside the crates and outside the crates, including the outside air temperature, alongside tracking their location. We found that in winter, some of the crate temperatures we were getting down to freezing, even in climate-controlled trucks.

For the vast majority of objects, it’s going to be okay. They remain unaffected by short-term temperature fluctuations. Inevitably, historic objects have had a variety of different lives and they have already, to some extent, been proofed to given conditions. Temporary changes in conditions are not always going to be problematic. However, certain collection materials are particularly vulnerable to mechanical damage during rapid temperature change, including composite objects, modern materials and synthetic polymers, waxes and adhesives, and contemporary works using food and bodily fluids, especially if subject to static load or vibration.

There might be cases where you would rather one material deforms rather than the other– I’m thinking about maybe when we are applying treatments. You might want some manoeuvre in an adhesive so that those are the areas that are moving and changing rather than the structures you’re looking to preserve. You kind of want any failure to occur in the treatment rather than the actual original object. Equally, if you’re looking to support an object, you don’t want the support material to be too soft – you want some structural integrity, and that structural integrity needs to persist over a range of environments and working stresses. It obviously depends on what you are trying to achieve.

I hadn’t considered that: the softness (for want of a better word) of the support materials matters as much as the softness of the materials being supported or preserved. Is this something you’re currently working on?

One of the things we’re looking at is 3D printed polymers and we’re really interested in how those materials are used to infill object losses, but also as support mechanisms. Think of the classic plate-stand in a gallery. You need a plate-stand to be strong enough to withstand, over time, the forces of an object working against it, but we also need them to be able to withstand changes in temperature and humidity.

We know that some of the materials used for 3D printing are particularly susceptible to moisture absorption, and moisture acts as a plasticiser. If you’re working in a collection or gallery that has higher humidity, that higher humidity may be perfectly fine for the object stability, but not for the 3D printed support mechanism. You might end up with creep (which is essentially deformation over time) occurring in the support mechanism, and therefore it’s no longer doing its job. To try to understand those properties, in terms of the environment’s impact on polymers, is something that we are interested in.

The question of the environment’s impact on polymers—on plastics—is an interesting one. There is much discussion today of the impact of plastics on the environment—their resistance to breaking down and the adverse effects they have on organic and geophysical environmental factors as they do begin to splinter into smaller and smaller parts. We might be surprised to hear that plastics need preservation.

It’s a good question—plastics are persistent materials; they persist in the environment, but they do change form. They might leach plasticisers, they might start to yellow and cross-link under ultraviolet light. So in the environment they are changing, but they remain persistent. That is where that tension comes.

From a preservation science perspective, we have had a desire to try to keep materials from changing, from degrading, from leaching plasticisers, from yellowing, from warping, and so I think that is where that tension sits: materials, and plastics in particular, are not going to remain the same. I guess that leaves some challenges for museums. At an institutional level and as a field, we have to learn to let go a bit more than we have historically, in terms of acknowledging some of the inherent vulnerabilities of these materials, which can come from the additives that might make them unstable or some of the residual components that remain in these materials from their processing. In the processing of different synthetic and semi-synthetic polymers, different components can remain in their structure which can cause long-term instability

These materials can be inherently problematic when trying to see them through the lens of our historical need to preserve and hold on to objects, especially given the high financial and environmental costs associated with managing collection environments. But I do think the field—and artists and designers—understand the material science, and the processes of collecting have changed to acknowledge that these vulnerabilities. People are more flexible as to how to accession these types of objects, and how to document them as they are changing.

You mentioned artists: what do you find is their relationship to materials changing and deforming?

I think are more aware of that and they maybe lean to using materials in their works because they change, because they evolve—it’s not static, it’s not in some statis.

That’s quite different to the early uses of plastics in Modernist sculptural works. I’m thinking specifically of the Naum Gabo sculptures in the Tate, or Antoine Pevsner’s Head (1923). They’re now falling to bits because the acetate or cellulose have degraded—and famously Pevsner’s Head smells terrible—but in the 1920s these new plastics were seen to be the impervious materials of a new age. Artists used them because they thought they wouldn’t degrade.

They were the future: a panacea.

Exactly. And now, in a relatively short space of time, we perhaps have seen a move away from plastics as the ideal stable material of the future to an acknowledgement, among artists, that they are more ephemeral.

The experimentation that came from those early those artists working with the early plastics is exciting. Would they do things differently? Who knows, maybe they would do things the same if they knew what we know now.

I think it’s exciting that artists do experiment with materials. Think of what a shame it would be if people stopped experimenting! But I don’t think that’s a danger. With what we know now, it is not necessarily about artists changing their practice. Some people will change that practice if that’s appropriate for them, but I think gathering as much information about material change as possible is not a bad thing. Others, I think, will embrace that change. There has been a move away from the constructivist aspect to more living works.

Is there an artist that exemplifies, to you, this living, changing approach to material science?

Is it César who was working with polyurethane foam? He was having performances which I think were interesting. The performances were very much embedded in the material science properties. At these events—called ‘Expansions’—they would pour out the polyurethane as a liquid polymer and it would flow, and as it started to cross-link and as gases started to percolate through the polymer to cause a foam, you would end up with these three-dimensional foam forms that had started off as a bucket of liquid polymer (Fig. 2). These objects would become a living representation or a document of that experiment and that performance. That kind of anti-form aspect of materials and materiality is situated around these ideas of soft and malleable and moving.

César’s works certainly chime with some of the disgusting, gelatinous aging you’ve encountered in your own preservation work. We’ve been thinking about artists’ relationships with material science, but what is it like, as a scientist, straddling these two disciplines?

Preservation science is a bit of a made up job. What does it even mean? You look at who works in this field and it’s people with conservation backgrounds, benchtop conservation, conservation research, people with physics backgrounds, microbiology, engineering, chemistry. It’s everything, it’s great, it’s exciting!

I actually trained as an objects conservator and then I retrained in the analytical sciences, so the jump, for me, was more from the humanities into the sciences. That has been hugely beneficial for what I do. I have historically had the hand skills for practical conservation and the theory and philosophy of conservation embedded in the things I do. Now, having retrained, it enables me to bridge the divide there and I hope it makes my research directly applicable to conservators. I would not have, necessarily, quite had the level of appreciation for what is tangible and relevant if I didn’t have the conservation background.

I think what is also important is understanding the context. We can do the analysis, but is it meaningful? That is why you need a cross disciplinary team—working with art historians and curators and other museums professionals—to make it tangible.

You must come across tensions—butting heads—in this meeting of disciplines.

In some instances cross-disciplinary collaboration works really well and in other cases it doesn’t, and it comes down to personality as much as anything else.

Where there are challenges, it is probably due to the fact that the field of conservation research—the field of heritage science and conservation science—has evolved so much and moved so quickly. Knowledge has not necessarily been transmitted to relevant stakeholders and so I think there is a danger, speaking candidly, that those in preservation science, heritage science, conservation science can be frustrated with the gaps in knowledge around material science at the institutional level. Equally, there is a danger of a disconnect between research and practice, and preservation research outcomes are often not deemed tangible for those professionals charged with the care of objects in collections.

On that thought of the object, what has been the most interesting object you’ve worked on? What has been one of your favourites?

I don’t know if I could answer that question! I love a textile…

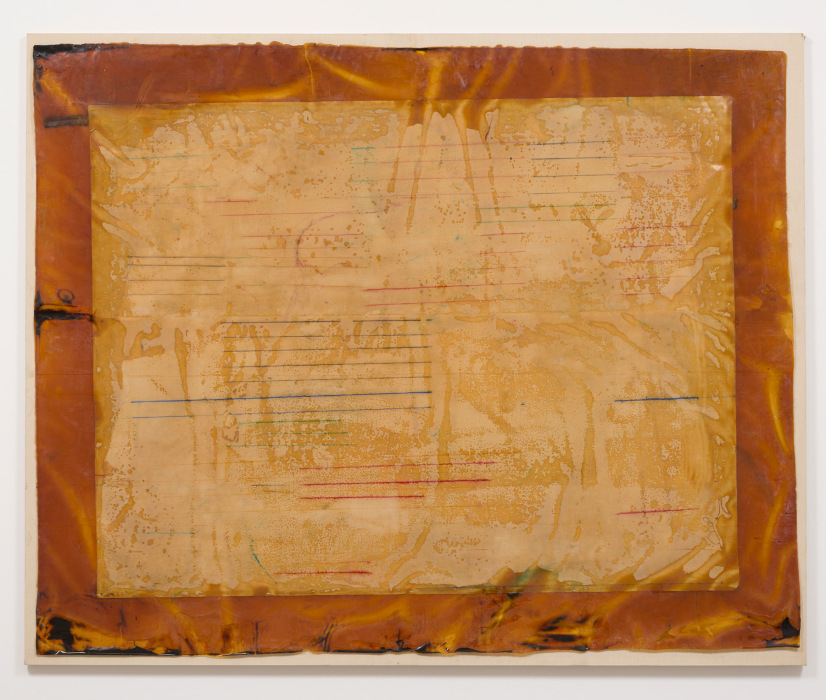

Actually, I think some of the most interesting objects are a series of works by Ed Moses, a Los Angeles-based artist who was working with canvas and polyester resins. They were known as the ‘Hegeman’ series (Fig. 3, 1970 – 72), and they resembled identity cards on a large scale. I worked on these with and they are interesting due to the fact they are made from brittle, thermosetting polyester resins. The resins have dyed canvas embedded into them and poured extremely thin. In some cases, the hard, brittle polyester was capable of being rolled up like a carpet, because of the way the artist had experimented with the resin materials meaning that the polymer reaction was incomplete and not capable of setting fully. Over time this has caused the aged resin to relax and slump and they also show signs of fine white deposits of the different additives in the polymer migrating to the surface. They look like large sheets of golden toffee, although I wouldn’t recommend licking them