Our History

The foundation of The Courtauld Institute of Art was presided over by a triumvirate of collectors, brought together by a common wish to improve the understanding of the visual arts in this country. By 1930 the idea of such an academic centre devoted to the serious study of the history of art had been in the air for some time. There were precedents in Europe and America, the critic Roger Fry and the fine art dealer Duveen had expressed interest; but there was also opposition, rooted in a deep-seated insular conviction that the arts were the playthings of the rich and not a suitable subject for a university education. Without the initiative and pertinacity of the founding fathers, Viscount Lee of Fareham, Samuel Courtauld, and Sir Robert Witt, it is doubtful whether the project would ever have got off the ground.

Our Founders

They came from very different backgrounds. Lee was the son of a Dorset rector who rose to eminence through the army, public service and government. During the First World War he hitched his wagon to Lloyd George’s star; it got him a peerage, but when Lloyd George lost the 1922 election, Lee’s political ambitions stalled, and his very considerable energies were redirected towards the arts. His first collection of pictures, not a great success, was donated to the nation along with Chequers; but his later efforts were more discerning, and went hand in hand with his scheme for a specialist institute, first mooted in 1927.

If Lee knew how and where to exercise influence, it was Courtauld who provided the bulk of the money. His wealth came from the textile business, but on both sides of his family there were connections with the arts and traditions of patronage going back several generations. Courtauld loved pictures and wrote poems about them. On the advice of Roger Fry and others he bought French Impressionists and Cézannes and took out a lease on the best Adam house in London, Home House, 20 Portman Square, in which to display them – a novel and stunning combination. His example was emulated by his younger brother Stephen, who converted the medieval ruins of Eltham Palace into an Art Deco mansion. Samuel Courtauld was the real Maecenas of the trio, and when his wife died in 1931, he made over the house in Portman Square, together with the pictures, for the use of the new institute until such time as permanent accommodation could be found for them. In the event the Portman Square house was to be the institute’s home for almost sixty years.

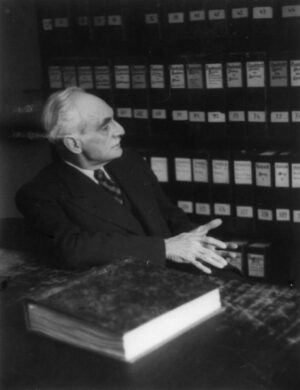

The third member of the group, Sir Robert Witt, was a successful lawyer who collected Old Master drawings; but his principal contribution to the enterprise was a vast collection of reproductions of paintings. These were to become in effect the surrogate primary sources for budding art historians. Witt’s collection had been conceived as a research facility for the art trade, but it was a ready-made teaching instrument, paralleled by the similar collection of Sir Martin Conway, who, by agreement with Witt, left the collecting of reproductions of paintings and drawings to him and concentrated on the rest of the visual arts. The Conway collection was also donated to the new institute.

The Early Years

The view of art which these men shared was bounded by a horizon that extended not much further than museums, galleries and private collections. Their aim was to provide a training for the professionals who intended to enter the various branches of the art business. They were anxious that it should be academic in the sense of being high-powered, but what they understood by history had little in common with the concerns of a university history department beyond an interest in chronology.

The first director, William Constable, who came from the National Gallery, fully shared their outlook, but he parted company with them, especially Courtauld, over whether or not the courses should be restricted to postgraduates. Courtauld, since he considered art important on the widest possible front, was insistent that art history should be taught as a first degree subject, whereas Constable wanted students who already held degrees in other subjects, and was acutely sensitive to the fear that the institute would become a finishing school. These were the issues over which opinions bifurcated from the moment the doors of the Institute opened in October 1932.

The case for making the institute exclusively postgraduate did not take long to surface, and there was a confrontation. In 1936 Constable offered his resignation to the Management Committee, of which Lee was chairman, and rather to his surprise it was accepted. This precipitated a crisis that took some time to resolve, and the next appointment, which had all the appearance of being a temporary expedient, turned out to be the first step in a fundamental reorientation of policy. On 12 December 1933, as a direct response to the advent of a Nazi government in Germany, the group of scholars attached to the Warburg Library at Hamburg decided to seek refuge abroad. Lee and Courtauld were instrumental in arranging for them to be resettled in London, and their presence slowly but inexorably transformed the perception of art history in England. The Warburg émigrés introduced standards of scholarship unknown among English art historians, and they practised a kind of art history far removed from the connoisseurship favoured by collectors and the art trade.

For the Warburg, the arts were inextricably bound up with the thought world of their time, and art history entailed research into the past, often of a rarefied academic order, in which the clear-cut distinction between history and art history ceased to exist. It was an approach that called for a formidable array of intellectual talents, and there was no great rush of British converts to this outpost of Mitteleuropa. One of the first to join was a research don from Trinity College, Cambridge – Anthony Blunt.

When the directorship of The Courtauld fell vacant in 1936, no suitable candidate applied for the post. Blunt, who was already attracting attention through his journalism, and recognised as the rising star in the art-historical firmament, was thought to be too young and inexperienced for the job, though his credentials were promising. The fact that his art history was coloured by his avowed Marxism was not held against him. It was after all the fashionable creed of his generation, and shared by many European art historians.

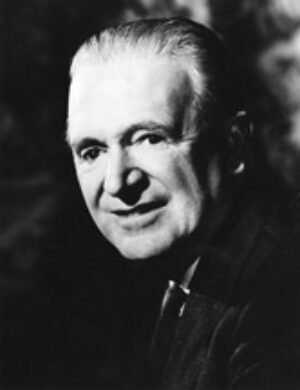

Until Blunt was ready, a temporary appointment had to he made, and a man was eventually found who was prepared to take it on these terms. This was Thomas Boase. Although a self-declared stop-gap, Boase left an indelible mark on the Institute in several ways, one of the most remarkable being that his connections with the art world were minimal. He came to The Courtauld from the Oxford history school, and it might have been expected that he would inject a proper respect for historical methods into the teaching practice of the Institute. Whether he made much difference is hard to say. Those who sat at his feet found him benign and inscrutable, and were in effect left to educate themselves, supervision on a very loose rein being standard Oxbridge practice at the time. The important thing is that with his arrival the pendulum began to swing away from the conception of art history as a professional qualification to that of its being a fully-fledged member of the humanities. Boase was also the first of the four medievalists among the six directors, and of all the subdivisions of the subject, medieval was the one that had least to do with collectors.

Boase hoped to hand over to Blunt in October 1939, but the war broke out a month before, and the Institute lapsed into a state of suspended animation for the duration. It did not exactly close down. The pictures were evacuated to the country for safety, and for a while students were taught at Guildford. Margaret Whinney kept lectures going at 20 Portman Square, doing for the visual arts what Myra Hess’s recitals at the National Gallery did for music. But despite her noble efforts to preserve the semblance of continuity, there is no escape from the conclusion that the war years cut across the history of the Institute like a hiatus, or that when serious academic life resumed again, to all intents and purposes it made a fresh start. In later years pre-war students often complained that they felt excluded by the intense aura of participating in something special which developed after the war. No doubt this was grossly unfair to them, but it was virtually inevitable, given the length of the interval and the sense of mission generated by the new dispensation.

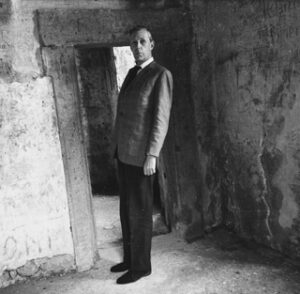

Sir Anthony Blunt

Blunt took office as director in October 1947. This is not the place to ponder the enigma of his personality, although the Institute cannot be understood without reference to it. Whatever prompted him to spy for the Soviet Union during the war, it was a commitment that ended in disillusionment, and, though it was a brief interlude in his career as an art historian, he soon came to realise that it had been an incredibly foolish error of judgement which was irredeemable, and would cast a blight over the rest of his life.

For more than thirty years he was, so to speak, a man on the run, never certain that he would not be exposed, and for most of that time constantly engaged in a damage limitation exercise. This was conducted with consummate skill and iron self-control. The allegiance to Communism was never formally disowned but allowed to recede into the past as a youthful indiscretion. He calculated, correctly, that the best way to allay suspicions of disloyalty to the Establishment was to join it, and despite being out of sympathy with royalty and the honours system, took service as Keeper of the Royal Pictures, and accepted a knighthood.

Given his background, accent, and Olympian demeanour, it was inconceivable that such a man could have been a subversive. Above all, the zeal and dedication with which he threw himself into the promotion of a harmless academic subject like art history, created the impression of a man wholly absorbed in a world where contemporary politics were not a primary concern. To suggest that he used art history as his cover in no way implies that it was bogus. On the contrary it worked only because it was absolutely genuine. If his luck had held he might have lived out his life under the immunity given to him in 1962. As it was, it lasted into his retirement, which was long enough to save the institute from any overspill of the odium that attached to his unmasking. This was not least among its debts to the immaculate sangfroid that concealed Blunt’s secret throughout his public life.

Blunt had no fixed ideas about the type of art history he wanted to be taught. He was not far short of forty when his career took off, and had acquired a wide acquaintance with the varieties of outlook which currently occupied the field. The one thing he was anxious to do was to distance The Courtauld, as far as was expedient, from the traditional insular attitudes that had inspired its foundation. Lee and Courtauld both died in 1947, Witt in 1952. Blunt himself represented the Warburg approach and specialised in the Baroque. His first appointment, to be his deputy and the high priest of the Renaissance, was Johannes Wilde, a one-time Marxist who had been involved in the abortive Bela Kun coup d’état in Hungary in 1919. Wilde came to England as a refugee in the 1930s, only to be treated as an enemy alien during the Second World War.

By 1946 any residual interest in politics had been drained out of him, and he took on an innocuous status as a distinguished representative of the celebrated Vienna school of art historians. Blunt’s second appointment could hardly have been more different. This was Christopher Hohler who replaced Boase as resident medievalist. Blunt could not have found his anarchic right-wing views sympathetic, but the appointment was a shrewd move. Academically Hohler was a pure product of the Oxford history school, obsessed by his primary Latin sources, and he looked at medieval art through the eyes of the patrons for whom it was made rather than those of the craftsmen who created it. This put him firmly on the history side of the balance between art and history among the components of the subject, and made him an unlikely progenitor of the new breed of art historians who appeared on the scene toward the end of the century.

Once he was firmly established, however, Blunt paid little attention to the political opinions of his teaching staff. What mattered were their strictly academic credentials; whether they were familiar with the art objects of their period, had read the relevant literature in whatever language, or could add discoveries of their own to the fund of knowledge. The operation was geared to research. Undergraduates continued to be taught, but the first degree came to be seen as a passport of eligibility to work on a doctorate, with the result that anything less than a First or a good 2:1 was tantamount to failure. Not unnaturally the atmosphere was highly competitive.

To a large extent this was the spontaneous response of the students to the way they were initiated into the subject. After the war many older art historians took the view that the primary tasks of art history had already been accomplished, and that the time had come for summaries. This was the platform from which Pevsner launched his Pelican History of Art project, but it was not how the situation was perceived at the Institute. On going over the ground again, it was apparent that in many areas the surface had barely been scratched. There were deeper levels to be penetrated, stylistic boundaries to be redrawn, reputations to be revalued, outstanding problems to be solved. The received version was no more than an interim report, and the opportunities for further work were legion.

An International Reputation

The Courtauld was an exhilarating place in the 1950s, a small powerhouse of intellectual activity that within the decade produced the agents of the campaign which put art history on the British academic map. It was certainly presided over by Blunt’s sense of purpose. In the eyes of the world, his persona and that of the Institute were virtually indistinguishable. But the controlling presence was imperceptible. The programme of research was left entirely to the students themselves. They chose their own topics, were at best advised, seldom if ever coerced, and allowed to mature in their own good time. A substantial proportion became the foremost art historians of the next generation, and it was they, not Blunt, who decided what the terms of reference should be in the future.

Constable’s hopes of attracting postgraduate students from the older universities were inherited by Blunt, and in the event his expectations were fully vindicated, though not perhaps in the way Constable had in mind. Since the war The Courtauld has received a steady stream of postgraduate recruits. They arrived with qualifications in history, literature, languages, even philosophy, which invariably coloured their approach to art history. This was an advantage in so far as it offset the risk of the subject becoming a narrow specialisation. Where the undergraduates excelled was at the modern end. During the 1960s there was a massive swing of interest among them towards twentieth-century art which, with the leadership of Alan Bowness, entailed a fundamental restructuring of the courses and put an end once and for all to the assumption that the Renaissance should form the obligatory centrepiece of every art-historical education. This was another reorientation which had far reaching consequences. Blunt’s interests, such as the work of Picasso, almost certainly helped The Courtauld in these respects. Equally, while he was certainly not a precursor of the new art history, the breadth of his interests (from practical art to history, the sciences, modern languages and literature) predisposed The Courtauld to an openness to such innovations.

Courtauld students were second to none in their dedication to the highest standards of historical research. In every section of the subject they were assiduous in trawling archives and libraries for clues to the thought world of their chosen periods. Style analysis, once the exclusive tool of the profession, was not rejected, but became one device among the many at their disposal. Blunt once described himself as an archaeologist of paintings, a reminder to those historians who derided style as a key to chronology that in principle it was no different from the method used with approval by archaeologists in the medium of potsherds, who, in the days before Carbon-14, had no other way of dating the strata of their excavations. If Carbon-14 had been available to date pictures The Courtauld would have used it. Right from the start the Institute had a technological department for the scientific examination and restoration of works of art which, under the stewardship of Stephen Rees-Jones, developed into one of the most highly respected departments of its kind in the world. Another aid to accurate dating came in the form of a history of dress department which became part of the Institute in 1965, followed by a department of wall paintings conservation in 1985.

The unremitting pursuit of excellence paid off in innumerable ways. It can fairly be said that in the twenty-eight years of Blunt’s tenure The Courtauld rose from being an inconspicuous attachment on the fringes of London University to a centre of international renown. Much of the credit must go to him personally, whatever the debit side of his reputation, but there were two other factors.

First the Polish scholar George Zarnecki, who arrived in Britain from the Continent in 1943 and served in the Polish army in the UK until 1945. He started work at The Courtauld in 1949 and held the post of Deputy Director through the last fourteen years of Blunt’s term of office. His influence cannot be overestimated, both on the international reputation of The Courtauld and because of the fact that he virtually ran the institute for Blunt.

The second factor was the rising tide of public interest in the arts. This added momentum to Blunt’s initiatives. In 1938 there were 45 students; in 1974 there were 220. Everything expanded exponentially: the book library, the photographic collections, the support staff, and most crucially of all, the teaching staff. For a long time all new members were Courtauld trained and simply co-opted by invitation; there were no competitions until the mid-1960s. The boom extended to the older provincial universities where art history was taught, and wherever new teaching posts were created Blunt’s advice was sought, with the predictable result that Courtauld graduates reaped most of the benefit. Others went to the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, India and elsewhere on the strength of Courtauld prestige, which in turn attracted many students from those countries. Still more opportunities for the placement of talented ex-students were provided by the new universities set up in the wake of the Robbins Report. Lord Robbins himself was chairman of The Courtauld Management Committee for almost the entire duration of Blunt’s reign, and together Blunt and Robbins, with the help of Sir Douglas Logan, ran it as the benevolent despots of a privileged fief.

Private benefactors were attracted by the Institute’s success. For twenty-five years, between 1956 and 1981, Barbara Robertson ran annual summer schools under the auspices of The Courtauld. These not only brought in many overseas students, but took subscribers to far away places such as Scandinavia, Andalusia and Armenia. Owners of country houses with collections of pictures, were, and continue to be, very willing to allow them to be photographed. The Institute’s core Courtauld collections were augmented by three notable bequests: Spooner, Gambier-Parry, and Seilern.

The Search for a New Home

What in retrospect has come to seem like a golden age gradually came to an end in the 1970s, when the national economy ran into a chronic crisis, and the flow of easy money to the universities began to dry up. But where the new financial constrictions impinged most directly on the Institute was in the matter of finding a permanent home for it when the lease on 20 Portman Square ran out.

This was the one task which Blunt consistently refused to face, right up to his retirement in 1974. He was much attached to his flat on the top floor, made no secret of his intention to remain there as long as possible, and was quite prepared to leave the problem for his successor to solve, even though he would have very little time. While he was director, accommodation seldom kept pace with the Institute’s growth for very long. Witt’s death in 1952 meant that his collection of reproductions could no longer be housed in 32 Portman Square, so No. 19, next door to the Institute, was taken over for the purpose. This eased the pressure for a decade, but by 1969 it was again acute, and the adjacent property on the other side of No. 20 was acquired (it was shared with the drawings collection of the RIBA). A temporary hut was built in the garden of No. 20 for the students; technology expanded along Portman Mews; every nook and cranny in the basement was pressed into service; but by 1981 when the lease finally expired the Institute was bursting at the seams.

When it was obvious that no solution to the accommodation problem would be found in time, Peter Lasko, who became Director in 1974, and Robbins, managed to persuade the University to arrange a transfer of the lease from the Home House Society. This enabled the University to negotiate extensions of the lease with Portman Estates, but only for short terms and at a vastly increased rent, which ensured that the respite would be brief. Provision had been made in the 1930’s Holden Plan for the development of the university site in Bloomsbury for purpose-built accommodation for the Institute alongside the Warburg in Woburn Square. The design was not exactly inspired, and no one was unduly upset, when, as a result of Blunt’s failure to press, planning permission lapsed before anything was done. The Warburg’s part of the building was however built, and this had consequences for The Courtauld, since the plan had envisaged a gallery for the Institute’s pictures spread over the top floor of both parts, and half of this became available when the Warburg took possession in 1958. A large part of the collection was put on view and opened to the public, but at the cost of separating the pictures from the students and the scene of teaching. Though in a sense the outcome of a chapter of accidents rather than a deliberate policy decision, this was a transgression of their intentions which the founding fathers would have deplored.

Lasko had been a student in Boase’s time, and, after a spell at the British Museum, he became head of a new department of art history at the University of East Anglia, where the subject came to be taught in a state-of-the-art building shared with the Sainsbury Collection. On his return to the Institute he relished the prospect of being involved in another up-to-the-minute design, and got to the stage of presenting the staff with a complete mock-up in the form of a three-dimensional architect’s model. But all hopes of obtaining new planning permission foundered on the refusal of Camden Council to sanction the further destruction of a terrace of listed buildings, part of which had already disappeared to make room for the Warburg. It was at this juncture that the question of what should be done with the Strand side of Somerset House came up for discussion in high places, and with his characteristic flair for the bold solution, Lasko switched from one extreme to the other and put in a bid which was eventually accepted, subject to certain conditions.

The choice of Somerset House was greeted with mixed feelings. For some it continued the association with a distinguished building, and reaffirmed allegiance to the perennial standards of fine art. For others it meant that an opportunity was lost to cut the traces with an irrecoverable past, and commit the Institute to the modern world. Whatever else it signified, Somerset House brought the Institute into the public eye in a way that its previous abode had never done. It lacked the discreet, well-mannered air of a London club, which made the house in Portman Square the perfect epitome of Blunt’s Courtauld; and there were many regrets at the ending of an era. But, for a time at least the accommodation problem was solved: the grand rooms of the new home allowed the collections (in the care of the Home House Society, at this point renamed the Samuel Courtauld Trust) to be reunited with the parent body and the Gallery could at last become one of the major tourist attractions of the capital. As for Somerset House, the arrival of The Courtauld could be construed as a first step in its transformation into a centre of art and learning.

The relocation took the better part of a decade to carry out. Securing the lease required not only negotiation with the Secretary of State and the Treasury but also, given the status of Somerset House, an Act of Parliament. A very large sum of money was required to adapt Somerset House to its new function, and fund-raising of a serious kind became a major preoccupation of the 1980s. Fortunately, Morton Neal, with a great deal of experience in the construction business, and Jane Benson, who understood fund-raising, gave unstinted service, and Sir Nicholas Goodison, who succeeded Witt (who had in turn succeeded Robbins) as Chairman of the Management Committee in 1982, was well-placed in his capacity as chairman of the Stock Exchange to help the cause along. In the usual way of things, first estimates of the amount needed fell woefully short of the mark. At the outset it was estimated at £3m, by 1987 it had risen to £8.9m, and by the end it had reached some £12m. Lasko retired in 1985 when most of the initial £3m had been raised, but by 1987 it was by no means clear that the increased amounts would be forthcoming.

It was left to the next director, Michael Kauffmann (1985-95) to see the project through to fulfilment. Work on the building was far enough advanced for the Institute to move in for the academic year which began in October 1989. Kauffmann not only oversaw the move, he also steered the Institute through the revolution in university accountability and an increase in student numbers, from 240 in the late 1980s to over 400 by the mid-1990s.

Looking to the Future

No sooner was the problem of accommodation out of the way than another took its place. As a small organisation devoted to the study of a single subject, The Courtauld was one of a cluster of similar institutes responsible to the Senate House of the University. When, as a result of the larger colleges pressing to become independent in the early 1990s, the University had to be drastically restructured, most of the Senate institutes were grouped together to form a comprehensive School of Advanced Study. Others were absorbed into the larger colleges, but The Courtauld was left in a state of anomalous isolation. It was the task of Eric Fernie, Director from 1995 to 2003, to sort out The Courtauld’s position. In effect the question was whether it should merge with one of the larger colleges or become a small, independent college.

The university attempted to force The Courtauld into another college, but, with the commitment of the staff, Sir Nicholas Goodison (Chairman of the Advisory Board), management consultants McKinseys, who worked pro bono (estimated cost £250,000), Lord Rothschild and major philanthropists and foundations who established an initial substantive endowment fund, Fernie succeeded in gaining independent college status for The Courtauld. Another Courtauld champion, Nicholas Ferguson became Chair of the new Governing Board.

21st Century

Professor Jim Cuno was appointed director in 2003 to lead the Institute through its first years as a self-governing institution. He left in 2004 to take up the directorship of The Art Institute in Chicago, having done much to foster The Courtauld’s links with the USA and to improve services and facilities for all its students. Dr Deborah Swallow, from the V&A, was appointed to succeed him with a mission to make The Courtauld better known to the world at large, to build on its new structures and to expand its sources of funding.

In January 2019, we opened our new campus at Vernon Square, King’s Cross. This move marked the start of our exciting transformational Courtauld Connects project.

Courtauld Connects

Courtauld Connects is an ambitious transformation programme that will make The Courtauld’s world-class artworks, research and teaching accessible to even more people – driving forward our mission to advance how we see and understand the visual arts.

The biggest development project since The Courtauld moved to Somerset House in 1989, this visionary project – supported by £11m from Lottery players via The National Lottery Heritage Fund and donations from generous philanthropic foundations and individual supporters – will transform the Gallery and facilities for teaching, research and students. It will create new dynamic spaces for temporary exhibitions, and enable the sharing of a greater variety of works from The Courtauld Collection with the public – displayed in a way that will be even more impressive and engaging than before.

Accessibility is at the heart of the project, with greatly improved visitor access throughout and the eventual aim of better connecting the Gallery with teaching and learning spaces. A new Learning Centre is also being created to expand support for schools, families, young people and adult learners.

Alongside the physical transformation of the buildings, The Courtauld is also undertaking an innovative programme of activity to ensure that everyone has the chance to engage with and enjoy art. This includes national and international loans of artworks, innovative digital events, school and community outreach work and creative volunteer programmes.

The first stage of Courtauld Connects was completed in November 2021, with the reopening of The Courtauld Gallery and the Learning Centre, and the construction of the West Wing Conservation Studios.