FOCUS: The Changing City: Monet and London

Devised by Courtauld Educators Francesca Herrick and Nadine Mahoney

Download the PDF: Monet and London

About the resource and exhibition

This resource explores a famous series of London views by French Impressionist artist Claude Monet (1840–1926) and helps you to look afresh at your own urban surroundings. It encourages you to make connections between changes taking place in the city in the 1800s and today. Following contextual discussion and close looking, you are invited to try Monet’s creative process via practical activities. You can see his paintings in high definition on our virtual tour of The Griffin Catalyst Exhibition: Monet and London. Views of the Thames.

London held a special place in Monet’s creative imagination, and this exhibition reunites an important series of paintings he began during three visits to the city in 1899, 1900 and 1901. He made close to 100 views along the River Thames, with a focus on three major motifs: Waterloo Bridge, Charing Cross Bridge and the Houses of Parliament. However, the works reunited here are distinct for being part of an original 37 that were presented to the public in Paris in 1904. These views of the Thames were conceived of and worked on as a coherent set. A huge critical and commercial success, they cemented Monet’s reputation as a leader of French Impressionism. It was Monet’s intention to hold an exhibition in London the following year, but plans never came together. The Courtauld show realises his ambition 120 years on.

Monet and Impressionism

Monet’s 1904 audience would have recognised the hazy atmospheres, luminous colours and modern subjects of his Thames series as typical characteristics of Impressionism. In Charing Cross Bridge (fig. 2), a steam train chugs over the river crossing to the North Bank, where silhouettes of the Houses of Parliament and leafy Embankment are just visible. Two small boats make their way through the thick fog that envelops everything. Attitudes had changed considerably since the first Impressionist exhibition of 1874, when around 30 rebel artists decided to hold an independent show that set them apart from France’s state sponsored education and exhibition system. Now, their technique of using soft and broken marks of colour was celebrated. In this series, Monet could dare to take his brush marks even further towards abstraction. In Charing Cross Bridge, manmade and natural elements

merge, as it becomes difficult to tell where structures end and reflections begin.

Impressionism is closely associated with painting from life and capturing the sensations of a particular moment in time. All of Monet’s paintings started with direct experience of the London views. However, by this relatively late stage in his career, he would also rely on memory and his own invention to complete paintings. All the canvases were worked on in his studio back home in Giverny, France (this is why some are dated after 1901). Managing the expectations of his art dealer, Paul Durand-Ruel, he described the works he brought back as “beginnings”. The freedom to move between works and change elements was essential to synthesising multiple canvases into one artistic vision.

London Context

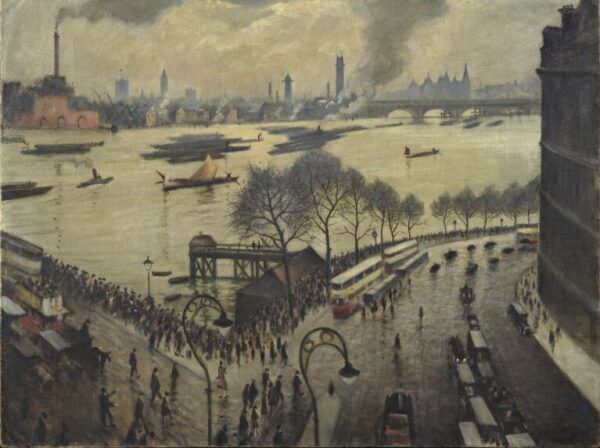

Monet first visited London in 1870 to escape the Franco-Prussian War. The city would have felt modern and exciting, but also strained by extreme urbanisation and industrialisation. It was the most populous city in Europe and global in character, with goods and people converging from the vast British Empire. The South Bank, as seen in Waterloo Bridge (fig. 3), was crammed with factories and warehouses. The north side was embanked in the 1860s to create a raised road and public gardens, but the South Bank was still prone to flooding and poor housing. Recent research by art historian Frances Fowle suggests that the effects of pollution in Monet’s Thames series were not exaggerated. The famous smogs that descended over London from the late 1800s to mid-1900s could be green, yellow and even purple in colour though the word smog itself wasn’t coined until 1905, so would not have been used by Monet when painting this series. Dust and gases from coal-powered factories, home stoves and steam transportation were the major pollutants. By the time of Monet’s later trips, the government was aware of the associated health risks and attempting to bring in some regulation.

Monet is known to have actively sought out the fog, deliberately choosing to visit London in the winter when the cold, polluted air and morning mists would hang over the Thames. He later told the art dealer René Gimpel, “without the fog London wouldn’t be a beautiful city. … It’s the fog that gives it magnificent breadth. Those massive, regular blocks become grandiose within that mysterious cloak”. Revisiting the city as an acclaimed artist, he was able to separate himself from its most noxious conditions. Between 1899 and 1901, he stayed in the luxurious Savoy Hotel on the Strand. The hotel, constructed in 1889, was itself a symbol of modernity as the first public building in London to be lit entirely by electricity and serviced by hydraulic lifts. From the upper floors, Monet enjoyed an elevated view of Waterloo Bridge to the east and Charing Cross to the southwest. Waterloo Bridge (fig. 3) gives perhaps one of the strongest impressions of city life with the teeming traffic.

Discussion Activity

Compare and contrast Monet’s views of Waterloo Bridge and Charing Cross Bridge with photographs of how the locations appear today:

• What has changed and what has stayed the same? You might like to consider transport, tourism, technologies, sources of energy, architecture, types of work and local population.

• What does London mean to you? Which areas or landmarks do you consider most representative of the city (you can answer these questions for any town or city you know well)?

Contemporary connections

Can you think of any contemporary artists who explore similar subjects and themes to Monet? Consider artists who are interested in the relationship between humans and the environment, such as Olafur Eliasson, and artists who revisit the same motif or viewpoint in their practice, like Frank Bowling, David Micheaud and Dominique White.

Art Activities

The warm up activity will encourage you to look in depth at Monet’s painterly techniques. In Activity 1 you will take inspiration from Monet’s method of working on multiple paintings at once by creating a series of sketches based on one view. Many contemporary artists also make art this way since it can remove the pressure getting it ‘right’ the first time and help explore diverse ways of seeing and experiencing a place. Lastly, Activity 2 will take you through the steps of developing your sketches

into a more finished piece before curating and displaying your works as a group.

Art materials:

• Oil pastels (or paint, chalk pastels or colouring pencils)

• A4 and A3 paper (a light-coloured sugar paper or cardboard)

Warmup Activity: Monet’s mark making

Using the virtual exhibition find Waterloo Bridge (fig. 3) and zoom into the sky.

- What kind of marks can you see and what directions do they move in? Are different marks used for different effects or elements, e.g. architecture/water/sky?

- How many colours has Monet used? Is there anything you find interesting or unusual about his selection of colours? How truthful to life do the paintings appear to be?

- Do you have enough information to tell the temperature, the time of day, the sounds and smells of the river, etc.?

Monet broke with painting traditions at the time by mixing colours together directly on the canvas and using the back of his paint brush to scratch lines into thick paint. Using a set of oil pastels, recreate Monet’s marks. Try to create short marks with the end of the oil pastel, and long marks with the side. To blend colours together, layer one colour on another and rub them with your finger. In areas where the oil pastel is thick, scratch lines into it.

Activity 1 — A view in flux

Step 1: Find inspiration!

- Use your local area for subject matter, especially if there is a scene that combines a river, bridge and architecture.

- In central London there is the Royal Festival Hall terrace (opposite the Savoy Hotel where Monet stayed), Somerset House terrace and Waterloo Bridge.

- If you are unable to work outdoors you can explore any locations, as well as Monet’s favourite locations, via google maps and images. It is important, where possible, to work from a real-life scene with changing light and weather conditions. Monet’s paintings began with direct observation. He would stop painting and start a new canvas once a

view took on a different feel.

Step 3: Urban motifs

On a new piece of paper create a simple sketch of the view. Try to capture the most important shapes, paying attention to fixed elements (like the buildings and bridges in Monet’s paintings. You have two minutes for this drawing.

Please note: Monet worked directly onto his canvas without sketching first. We have suggested this activity to help you look closely and choose your composition. You can avoid this step and work directly like Monet if you wish!

Step 4: Changing light

Working from the same viewpoint, make a drawing on a new piece of paper, paying attention to changes in light. Look for any shadows and try to identify the lightest and darkest parts. Like Monet, avoid using black or grey. You have 3 minutes for this drawing.

Activity 2 — Personal response to place

Step 1:

Choose your favourite image from Activity 1 as a starting point. Using a light- coloured oil pastel sketch out the same composition on a A3 piece of paper.

Step 2:

Choose your colours carefully, thinking about what time of day, season and weather you are capturing.

Step 3:

Test out making marks on scrap paper. You might choose to hold your oil pastel in different ways, blend or overlap colours, or scratch back into the pastels using a stick or the end of a pencil or palette knife. This is an opportunity to experiment just like

Monet. His painting technique broke with tradition. He would mix colours together on the canvas and use the back of his paint

brush to scratch lines into the thick paint.

Step 5: Curate and display the finished artworks

Monet approached the Thames paintings as both an artist and curator. He stated they “take on their full value only in the comparison and succession of the entire series” (quoted in Bijvanck, 1892). The process of looking from one closely related artwork to another encourages a deeper level of perception and engagement than looking at a single image.

Monet had already created smaller series in the early 1890s, such as his Rouen Cathedral series. Significantly, he had the Thames series professionally photographed.

Extension activities

- Take your oil pastel drawings to the same viewpoint and rework them outside.

- Continue the series. Make more of the same or similar viewpoint then discuss the similarities and differences.

- What sounds might be heard in your picture? Using items you can find in your classroom or home, record sounds to accompany your landscape. You could make a short atmospheric video.

- Scan the image into a photo-editing programme and add filters to make three more images.

Related artworks in The Courtauld Collection