Introduction: A ‘cope’ that wasn’t – the power of conservation

My introduction begins with a brief story that might raise a smile – or at least an eyebrow – not about a wall painting but about a ‘cope’ that wasn’t. Well over fifty years ago, a startling discovery was displayed at the 1972 exhibition in Pisa of recently restored works of art. Thanks to conservation detective work, a textile which had been venerated for many centuries as the cope of Saint Guido turned out to be the rump-half of a horse caparison (Llancarfan’s horse, Figure 2, provides a helpful illustration).

That revelation, worthy of an art-historical detective novel, still serves as a striking reminder of how conservators can fundamentally reframe an object’s identity; it captures the hands-on, evidence-based power of conservation – through meticulous examination of materials and structures – to deepen or transform our understanding of artworks.

Even seemingly minor discoveries, to which conservators are accustomed, have the potential to rewrite entire narratives and solve hitherto persistent historical puzzles – including architectural puzzles. It was precisely these ‘lightbulb moments’ that inspired the late Anna Hulbert to organize the 1992 conference, The Conservator as Art Historian.

A Courtauld-trained art historian and conservator, Anna embodied the synergy between these two disciplines. Her work on the polychromy in Exeter Cathedral and the Jesse Tree ceiling in St Helen’s Church, Abingdon (Oxon.), demonstrated how on-the-scaffold investigation paired with desk-based research can yield the deepest insights. In her preface for the 1992 conference, Anna emphasised how ‘meticulous analysis of the order of plaster [and limewash] layers is the only means of clarifying a complicated history of redecoration’.1

In this short talk I hope to honour Anna’s legacy by highlighting, once again, how much more we all learn – and how our perspectives can evolve – when conservators can think like art historians and when it becomes the norm rather than the exception for conservators and historians to share discoveries in real time.

A personal retrospective leading to a call for change

Since 1992, conservation and art history have benefited from remarkable technological advancements. With powerful imaging techniques, spectroscopy and ever-expanding comparative databases, our capacity for uncovering and sharing new information has soared. And yet, despite these tools, fundamental issues persist: institutional support for specialised, integrated training still lags behind and opportunities for conservators and art historians to collaborate in a structured, systematic way are too often limited.

Anna Hulbert’s vision still resonates. The importance of studying a building’s archaeology and understanding how plaster and paint layers accumulate cannot be over-stated; they help us to decode a painting’s true history – a history that art historians, in turn, embed in wider cultural contexts. Without sufficient training and proper channels of communication, vital findings from the scaffold are at risk of never entering broader historical discourse. Adequate funding remains a serious obstacle; funding cuts and packed curricula mean that professional training for conservators seldom includes robust art-historical grounding – and wall paintings are a field where this is especially significant.

However, organisations such as Icon – our professional body – could make a real difference. They could establish formalised professional development modules in art history for conservators, and particularly for wall painting conservators – imagine the confidence and fluency they would gain in contextual analysis. Ultimately, this would not only enhance accreditation but also ensure that those ‘at the coalface’ of discovery are much better prepared to interpret iconography, stylistic nuances, and historical sources.

When a wall paintings conservator seeks to embrace these contexts, their increased knowledge and awareness is evident in a heightened sensitivity and in their hands-on ability and, consequently, in their overall approach to practical treatment. They are more alert to the most obscure brushstroke or smallest paint fragment revealing far-reaching clues, and art historians benefit from more precise, evidence-based insights about a painting’s physical state.

Two parallel perspectives: on the scaffold and at the desk

Conservators work directly at the surface, employing minute and tactile examinations of the materials, using magnification, and other methods of analysis, to reveal how layers of paint were applied or reworked. Informed by conservators’ findings, historians can reference broader contexts – documentary sources, devotional practices, style comparisons – and locate each painting in a continuum of artistic development.

Blending these views is like merging a microscope with a wide-angle lens. Without thorough technical analysis a mis-identified figure might remain so, while physical details can be meaningless without an understanding of the wider cultural, artistic and theological landscape of the period. Collaborative detective work ensures critical insights are not missed and that even small discoveries enrich and reshape our collective understanding.

Llancarfan

The project to uncover and conserve the fifteenth-century wall paintings at St. Cadoc’s Church in Llancarfan began in 2008. I was joined by Ann Ballantyne, and we worked on it together, exclusively, until her retirement in 2015. Since 2018 there has been a long break (on account of serious problems of groundwater ingress, plus Covid-19) but I shall soon be returning to continue the work there.

From early on, the project exemplified the importance of interdisciplinary research.

Seven eminent historians, all specialists in different fields, visited the church (three of them several times) and joined us on the scaffold, examining the paintings at close quarters, discussing the details we had found and the iconography, very generously volunteering and sharing their knowledge and support. Our knowledge sets intersected: we discovered material evidence; they recognized its significance in the broader historical tapestry. Often with their guidance, we then pursued many more lines of research in our own time, away from site.

This kind of collaboration – where conservators, historians, together with scientists, can meet on site – is an ideal (the ideal); the merging of expertise has created a much deeper narrative of Llancarfan’s past than would otherwise have been possible. However, this project has been an exception because of the paintings themselves – their individual content, their iconography and the extraordinary amount of detail that survives, not to mention their overall scale; many elements are extremely rare, if not unique.

So it is important to recognise that, for many wall paintings projects, achieving such collaboration may be very difficult – or even seemingly impossible – often hinging round financial considerations and, occasionally, negative aspects of competition. Almost inevitably it falls to the conservator, also, to perform a pivotal role as a facilitator and intermediary, as well as a repository.

At St. Cadoc’s, the discoveries and insights are too numerous to present more than just a snapshot of them here – the Llancarfan chapter in Richard Suggett’s book is a fairly comprehensive summary, 2 but I have a full monograph in progress. Starting with the central scene of ‘St. George’, the portrayal of the saint and the extent to which the details of his armour have survived, together with the trappings of his horse, are quite remarkable and Dr. Tobias Capwell has been the critical guide in their appraisal and interpretation.

The horse has its own symbolic force in paintings of this type, as we are reminded by R.W. Southern and F.S. Schmidt whose Memorials of St. Anselm (Oxford, 1969) tells us that ‘the horse is the Body disciplined in the battle against evil in the pseudo-Anselmian Similitudo militis, where every element of knight and horse’s equipment is allegorized’ – a reference sourced through Anna Hulbert’s studies of Exeter Cathedral’s polychromy.3

Every element of this enormous picture is rich in symbolism. The most extraordinary element of all is the inclusion of the Virgin, Queen of Heaven and Mother of God, identified by her flowing hair, her crown and her halo and, beneath her ermine-lined mantle, her laced maternity gown. The artist shows her apparently giving divine power to St. George’s lance, supporting her champion in his battle to vanquish Satan (the dragon): she is depicted with her right hand raised in blessing, a gesture normally reserved for God the Father and Jesus, Son of God. The illustration appears to be unique and we were particularly grateful to Sir Roy Strong for drawing attention to this.

Another prime subject of research is the matter of patrons. Two shields have survived, both holding clues. Fortunately, the one directly above the Virgin is quite clear and this has been firmly identified by Professor Ralph Griffiths as bearing the arms of the Bawdrepp family – sable three swans argent. The family originated from Somerset and eventually one Sir Thomas Bawdrip went on to become ‘constable of Newport castle for life, and squire of the king’s body’ in 1483. Richard III described him as ‘our welbeloved servant’.

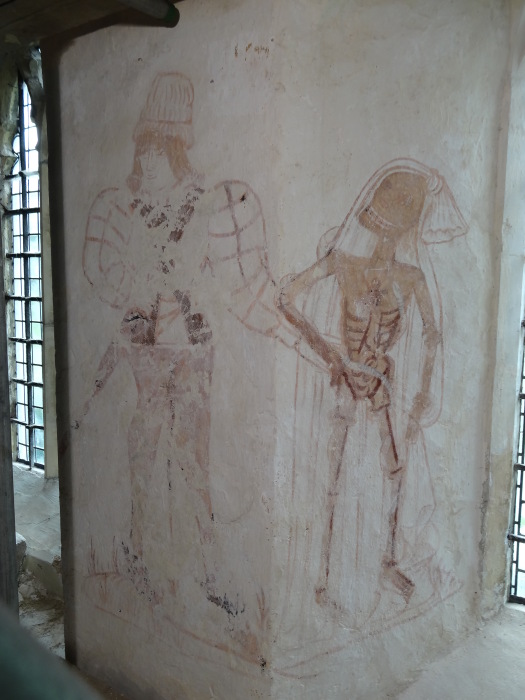

Two artists, one limewash layer: ‘Death and the Gallant’ and the main cycle of paintings, which begins with St. George et al and continues with the Deadly Sins and Works of Mercy (round the aisle’s west end), were executed on the same layer of limewash. This was one of our most significant early discoveries, confirming that, although by different hands, the paintings were created in close succession. That ‘Death and the Gallant’ came first is indicated by the way the ‘St. George’ artist carefully respected the earlier work in the use of the wall space immediately above for his depiction of the castle.

Throughout all the processes of uncovering, many details were found which, at least initially, were visible only to us, the conservators. One such, in the main cycle, and barely visible even under magnification, is the use of lead-tin yellow to portray paint or gold thread – a valuable clue about the desired visual effect and the resources available to the workshop. Only minutely thin traces survive in the elaborate design on the red cloth covering St. George’s upper cuirass (breastplate) and on his flying red sleeves; it was also used to represent gold embroidery on Gula’s coat.

Above and west of the south doorway, in his painting of ‘The Seven Deadly Sins’, the artist continues to demonstrate his wonderful ability to portray the sensual and the terrible. Although Gluttony is a bloated wretch no longer able to fit in his clothes, by the embroidery and the quality of its buttons his coat shows him to be a man of affluence.

Fig. 8 Accidia (a rare portrayal of Sloth) from the Seven Deadly Sins, south aisle, west wall, St. Cadoc’s Church, Llancarfan (2015). © Jane Rutherfoord

Figure 7 shows a familiar image of Sloth but the Latin label uses the more unusual spelling Sompnolentia (rather than Somnolentia). This image overlaps with the depiction of Accidia (another interpretation of Sloth) (Figure 8), and one might have expected that this seventh scene would depict Invidia (Envy). Why it was decided to omit this more familiar Deadly Sin and to portray both Somnolentia and Accidia remains an intriguing question and a continuing avenue of research. Moreover, Llancarfan’s depiction of Accidia is highly unusual because suicide was associated with the vice of Tristia, a sin of apathy, melancholy and despair; but Accidia remains acknowledged to this day as the most difficult of the Sins to define.4

For inclusion here, about the painter’s skill and technique, there are two last, significant points: although he is likely to have been copying sketches, there is no evidence of any preparatory work on the walls – there are no incised lines or under-drawing – and there is no evidence of corrections. Careful scrutiny is needed to detect that the red lines which frame the subjects of the main cycle were painted in at the end – probably by an assistant – after all the figurative work had been completed. The artist was obviously supremely confident and an absolute master of the use of space for dramatic impact.

To analyse and fully understand these paintings it was essential to understand the archaeology, namely the nature and chronology of the overlying layers as well as the paint layer(s) of the scheme itself and the underlying, supporting layers. One of the main roles of the conservator is to be that archaeologist. Going forward, this case study highlights why we must develop systematic protocols for interdisciplinary research. Publications authored jointly by conservators and historians should become standard practice, ensuring that new findings are disseminated in a holistic manner. This approach would dovetail neatly with a broader initiative to instil art-historical competencies in all practising conservators.

Conclusion and call for change

We’ve made important strides since 1992, but there’s more to do. Conservators need formal channels to develop art-historical fluency – ideally woven into accreditation itself. This shift transforms them from skilled technicians into historically astute detectives, capable of recognising deeper meanings in every layer of paint – or limewash.

Art historians, we need you on the scaffold, too. By examining evidence revealed only through conservation work, you can confirm or overturn theories about style, iconography, identity, and sometimes authorship. If we share insights in real time, the risk of previously hidden or misunderstood features and details slipping by unnoticed could be avoided.

Anna Hulbert envisioned a future free of silos; she highlighted how crucial it is that conservators share their on-site revelations with historians so that identification errors do not persist, and lost layers of meaning are, at last, recovered. The ‘cope that wasn’t’ was a powerful early signpost.

The issues I have been describing have far-reaching implications, not only for the integrity of conservation work but also for our collective understanding of cultural heritage. The National Wall Paintings Survey database, publicly accessible, is now the most positive and significant new step forward towards addressing these issues.

1 Anna Hulbert, in A. Hulbert et al., The Conservator as Art Historian: papers given at a UKIC wall paintings section conference on 20 June 1992 at Abingdon, Oxfordshire, (The United Kingdom Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works of Art, 1992), 2.

2 See Rutherfoord’s chapter in Richard Suggett, Anthony J. Parkinson, and Jane Rutherfoord. Painted Temples: Wallpaintings and Rood-screens in Welsh Churches, 1200-1800 (Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales, 2021, 147-178.

3 See Avril K. Henry and Anna C. Hulbert, Exeter Cathedral Keystones & Carvings – A Catalogue Raisonné of the Medieval Interior Sculpture & Its Polychromy (2000), http://hds.essex.ac.uk/exetercath/index.html (accessed 20/03/25).

4 See Suggett et al., Painted Temples, 169.

Bibliography

Henry, Avril K., and Anna C. Hulbert. Exeter Cathedral Keystones & Carvings – A Catalogue Raisonné of the Medieval Interior Sculpture & Its Polychromy, 2000. http://hds.essex.ac.uk/exetercath/index.html (accessed 20/03/25).

Hulbert, Anna, Julie Marsden and Victoria Todd (eds.). The Conservator as Art Historian: papers given at a UKIC wall paintings section conference on 20 June 1992 at Abingdon, Oxfordshire. The United Kingdom Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works of Art, 1992.

Suggett, Richard, Anthony J. Parkinson, and Jane Rutherfoord. Painted Temples: Wallpaintings and Rood-screens in Welsh Churches, 1200-1800. Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales, 2021.