Studying wall paintings is a complex task. Their locations are not exactly forgiving: they are geographically dispersed, usually in small rural locations, and are often closed. If you manage to get inside, the sites are usually far from hospitable: cold, damp, and, in the worst cases, full of bats and dead insects, which makes the whole process rather unnerving. The murals themselves are sometimes in such poor condition that you cannot make out what they once showed. Others are in suspiciously good condition, suggesting they have been repainted, obscuring evidence of the original schemes. Pigments can be altered making interpretation even more challenging. Sometimes multiple images are painted on top of one another, making figuring out what once adorned the walls a perplexing task. They are terribly difficult to photograph and record, with dark and changeable light conditions and imagery usually high up and difficult to access.

Survivals of murals, especially extensive schemes, are rare and important documents of the past. Yet many wall paintings have no direct documentary evidence and no conservation or technical analysis to use as a starting point. For medieval British wall painting, which this essay focuses on, Charles Keyser’s important tome for the V&A, listing both destroyed and extant murals, and volumes by conservator and art historian E.W. Tristram occasionally erroneously identify iconography too.1 These aspects leave us with a problem. How do we navigate these challenges, and base our analysis on the evidence? I plan to consider the methodological and archival issues facing research of English wall paintings.

The material evidence: conservation, copies, and loss

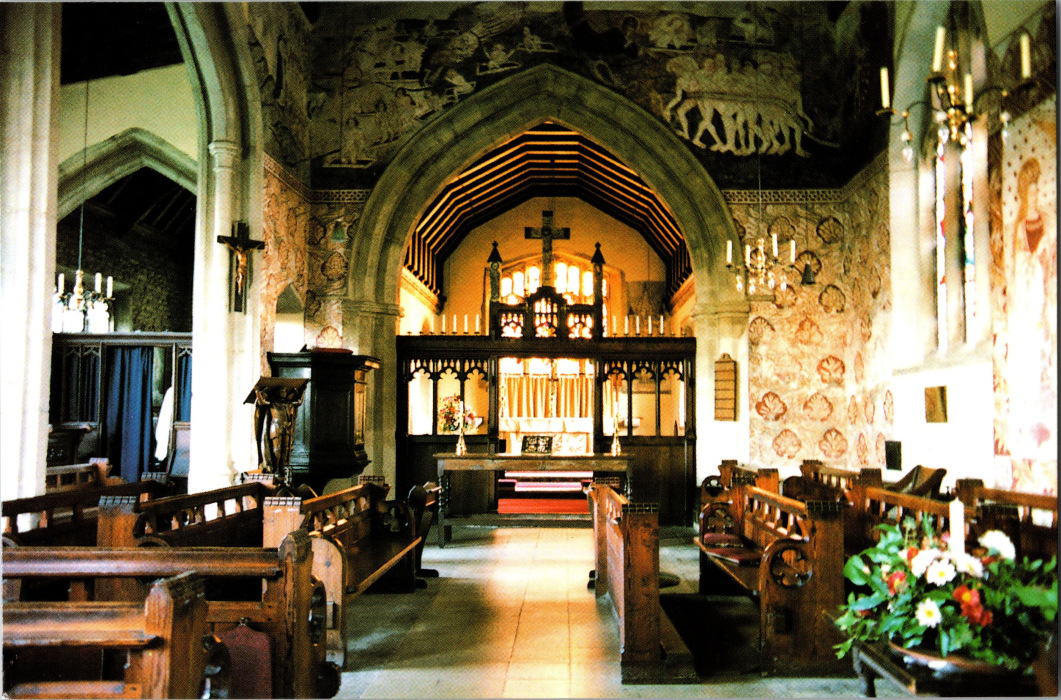

A good example for navigating the difficulties of researching wall paintings is a scheme in the church of St Pega’s Church in Peakirk, Cambridgeshire (Figure 2). When the paintings were first fully uncovered by conservator E. Clive Rouse between 1950 and 51, they were identified as a series of twelve images of the Passion, St Christopher, the Warning to the Gossiping Women, Three Living and Three Dead, and an unidentified female saint.2 Bar the Gossipers, they all have the same chevron border, which indicates they were conceived as one whole scheme. The iconographies suggest a late medieval date, in particular the inclusion of the Warning to the Gossips and the Living and Dead, as this was when they were popular in wall painting. A lot of their detail, however, which might help us to understand the scheme, has been lost. One of the skeletons of the Three Living and Three Dead has been entirely lost due to a plaster repair, many scenes of the Passion sequence are fragmentary, and the St Christopher is almost indecipherable.

The first question is to establish the physical history of the murals, to begin to understand what exactly we are seeing. Some wall paintings have a history of conservation information which can be found in the National Wall Painting Survey, and sometimes the Historic England files, parish church archives and local archives. For Peakirk, Rouse helpfully left a published article describing the mural imagery in detail and a series of paintings of the scheme which can be found in the Society of Antiquaries in London.3 Here was a record of the entire scheme as uncovered (Figure 3). Rouse’s drawings were intended as an accurate restorer’s copy of the murals, and therefore they can be used, with caution, to understand the iconography of the scheme.

This evidence suggests several things. Firstly, some parts of the wall paintings had been lost before they were even uncovered. The damage to the Three Living and Dead and some of the Passion scenes (Figures 4 and 5) was due to heavy iron ties bolted through the walls in the mid-nineteenth century.4 Secondly, some of the paintings were also fragmentary when uncovered: the Warning to the Gossipers was such an incomplete image that conservator and art historian E.W. Tristram published it as a fragment of the Seven Deadly Sins.5 Thirdly, it was clear that their condition has significantly deteriorated. Rouse had coated them with wax in an attempt to preserve them. However, this traps dust and dirt particles, darkening the murals, and stops the evaporation of water and salts, causing a white residue (efflorescence) on the surface of the murals and flaking paint. This led to extensive deterioration of the paint layers – the St Christopher for example is almost completely lost, and the detail of the donor figure and mermaid has become quite unintelligible. Therefore, the first major challenge for those attempting to study and identify mural schemes is navigating their fragile and deteriorated condition.

Fig. 5 E.C. Rouse, 'Christ Mocked and Buffeted', north nave arcade, upper tier, copied 1951, scale 1/3. ROU/01/36 (4). Reproduced with the permission of the Society of Antiquaries of London.

More recent conservation records can help us to understand how the murals’ appearance may have altered. For Peakirk, the National Wall Painting Survey holds conservation material from the 1990s by wall paintings conservator Tobit Curteis. Paint samples were taken from various parts of the scheme, which showed that pigment alteration had taken place. In the Gossipers image, the black of the dress of one of the Gossips had altered from red (Figure 6), as had the sleeves of the first of the living kings in the Three Living Three Dead (Figure 7), changing the original visual effect.6 For the Gossips it may change their symbolic meaning too, obscuring the fiery red associated with the Magdalene and sinful women.7

Fig. 7 Alteration of pigment to black on the sleeves of the first of the living kings, St Pega's Church, Peakirk. Image: Florence Eccleston.

The analysis undertaken also meant that pigments were identified: ochres, lime white, carbon black, and some more expensive pigments including red and white lead and vermillion.8 Examination with raking light showed the original planning process for the paintings with carefully incised laying out lines into the plaster indicating a sketch.9 Together this investigation into the materiality of the paintings suggests a carefully planned scheme of moderate expense. Therefore, conservation information helps us significantly to understand what we are seeing: what is original, what has deteriorated, and what has changed. Without such records, substantial caution is demanded in interpreting the material evidence, so fragile and changeable over time.

Getting beyond the material: image as evidence

Without contracts or site- and time-specific documentary evidence, of which there are usually none at all, it is difficult to get beyond the materiality of the paintings.10 Questions of when exactly a scheme or individual image was painted, who paid for it, and who did the work are largely elusive. This makes it difficult to situate these paintings within a particular time and place, inhibiting our interpretation of them. However, if we don’t try, we lose a vital aspect of what these images meant to those who created and viewed them.

We can attempt to be more specific in our dating of wall paintings. As a starting point, architectural evidence can be very helpful – for example, if a wall painting appears in a chapel dated to the fourteenth century, it indicates the earliest date a painting could have been painted. Iconographies also need to be identified – is there a date at which particular iconographies start to appear, and does their presentation change over time? In some cases, such as at Chaldon in Surrey, there are no other surviving purgatorial ladder iconographies in medieval English wall painting, and its unusualness also does not easily point to a particular manuscript comparison. Stylistic analysis is a crucial tool in this case, looking carefully at the forms within the painting and how they might be comparable to tendencies in other imagery in manuscripts or sculpture, for example, of a similar date.

This approach is also crucial for dating the scheme at Peakirk more precisely. In the National Wall Painting Survey, many articles focus on isolated individual iconographies and date them separately. Therefore, multiple dates from c.1320 to the mid-fourteenth century were suggested.11 However, this did not take into account that they were part of one scheme. A few factors helped to narrow down the date – the clerestory has been dated to the fourteenth century, and some of the paintings in the scheme are painted upon it.12

Clothing evidence is also a helpful way to narrow down a date further. Using nationally or, perhaps more helpfully, locally produced manuscripts and sculpture such as tomb imagery for example, can help to closely evidence a date (exercising caution over their dating too). At Peakirk, the mid-fourteenth century date is most clearly evidenced by the youngest of the Three Living (Figure 8), who as a symbol of youthful pride in appearance, can be assumed to be wearing fashionable clothes. Most helpfully, his clothing matches those of the Three Living in the Smithfield Decretals (c.1330-40, British Library, Royal MS 10 E IV). However, having been able to establish the murals were part of a scheme, cumulative evidence could be used to confirm a date of between approximately the early to mid-fourteenth century, approximately the 1320s to the 1360s.

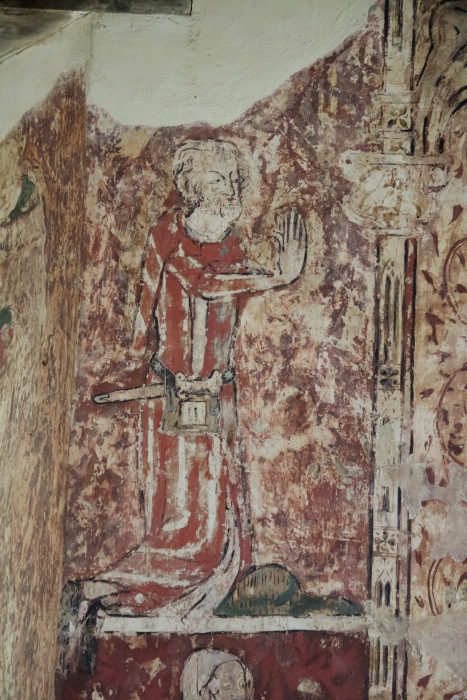

Having established a date, the ‘who for’ question can also be addressed. A donor figure kneeling in prayer with a prayer scroll is recorded by Rouse in his article and watercolours as being beside St Christopher, and suggests a singular donation of the scheme at Peakirk. Rouse’s evidence (Figure 9) suggests the figure is bearded and dressed in a cloak with tippets, indicating he is not a member of the clergy or a monastic order, but instead a secular donor. Diminutive donor figures are found in many mural schemes in England, and those of a similar date to Peakirk include nearby Nassington in Northamptonshire and the impressive scheme at South Newington in Oxfordshire, where donor figures have been identified as Thomas and Margaret Gifford (Figure 10), suggest their donation of murals in at least the north aisle chapel.13 Heraldry is also often found and indicates a particular individual wished to be associated with the commission of murals. The inclusion of the donor figure in the scheme at Peakirk suggests an individual motivation for paying for a scheme of murals in the mid-fourteenth century. Therefore, accumulating evidence of the imagery within the scheme helps to establish a date, and donor figures and heraldry indicate who may have paid for a mural scheme, giving a solid foundation to begin to explore the wider history of the murals.

A wider understanding

Having established the materiality of the murals, their date, and perhaps who may have been involved in the commission, we can turn to contemporaneous archaeological and social history to give a closer understanding of its context. We can look at local history to understand what was occurring in that particular place at the particular time the murals were painted – who controlled the church and the manor or perhaps, in the case of domestic murals, who lived or worked in the building? Is there tax information to suggest how many people lived there, and therefore who might have seen the murals week on week?14 Bringing a wider understanding by using texts, objects, and images dating to a similar time period help to open up the meaning of schemes in their particular place and time. In the case of church murals, such as Peakirk, sermon texts can help to illuminate attitudes in ecclesiastical contexts to the themes shown – the immorality with which gossip was understood and the warnings of the coming of death, for example.15 This helps us to comprehend how a viewer may have understood what they were seeing.

However, we have to remain speculative. Going beyond the physical history of wall paintings demands interdisciplinary research, looking through a constellation of different types of sources, for example local social history, contemporary sermons, and devotional and even medical treatises, to bring out more of the contextual understanding of the imagery within the emotional and lived experience of their viewers. By navigating the initial challenges in understanding our material – which the National Wall Painting Survey has made so much quicker and easier, and even, in some cases, just possible in the first place – we build a strong foundation to begin asking these more daring and theoretical questions.

1 C.E. Keyser, A List of Buildings Having Mural Decorations (Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1883); E.W. Tristram, English Medieval Wall Painting: The Twelfth Century (Oxford University Press, 1944); E.W. Tristram, English Medieval Wall Painting: The Thirteenth Century (Oxford University Press, 1950); E.W. Tristram, English Wall Painting of the Fourteenth Century (Routledge, 1955).

2 E.Clive Rouse, ‘Wall Paintings in the Church of St Pega, Peakirk, Northamptonshire’, Archaeological Journal 110, no. 1 (1953): 135–50.

3 The paintings can be found under London, Society of Antiquaries, ROU/01/36.

4 Tobit Curteis Associates, ‘Technical Examination and Proposals for the Conservation of Wall Paintings, St Pega’s Church, Peakirk, Cambridgeshire’ (September 1996).

5 Tristram, Fourteenth Century, 235.

6 Tobit Curteis Associates, ‘Technical Examination’, 6.

7 For the colours associated with the Magdalene and the meaning of white in the Middle Ages, see Herman Pelij, Colors Demonic & Divine: Shades of Meaning in the Middle Ages & After, ed. Diane Webb (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004), 15, 46, 68. In fact, the Magdalene is painted in red lead in the 15th or 16th -century wall paintings at St Nicholas’s Church, Glatton, Cambridgeshire, just as the Gossiper is at Peakirk. See Tobit Curteis Associates, ‘Condition Survey and Proposals for the Conservation of Wall Paintings: St Nicholas’ Church, Glatton, Cambridgeshire’ (n.d.), 4.

8 Helen Howard, Pigments of English Medieval Wall Painting (Archetype Publications, 2003), 98, 99, 126, 142, 160, 176, 187.

9 Tobit Curteis Associates, ‘Technical Examination’, 3.

10 A helpful article for navigating archival sources is Ellie Pridgeon, ‘Researching Medieval Wall Paintings: A Guide to Archival and Unpublished Sources in England and Wales’, The Local Historian 45, no. 1 (2015).

11 Ellen Ross dated the Passion to the fourteenth century in Ellen Ross, The Grief of God: Images of the Suffering of Jesus in Late Medieval England (Oxford University Press, 1997), 59.; Miriam Gill gave a date of 1320 for the Three Living and Three Dead, citing Rouse’s dating which relied on the evidence of a pocket in the Gossipers image: Miriam Gill, ‘Late Medieval Wall Painting in England, 1330-1530’ (PhD Thesis, The Courtauld Institute of Art, 2002), 190., and Rouse, ‘St Pega’, 137, 147.; R. Bowdler suggested c.1330 of the Three Living and Three Dead, whilst Sophie Oosterwijk just the fourteenth century: R Bowdler, ‘The Treasury of Death: The Imagery of Mortality on Cambridgeshire Monuments’, in Cambridgeshire Churches, ed. Carola Hicks (Stanford, 1997), 269.; Sophie Oosterwijk, ‘Food for Worms – Food for Thought: The Appearance and Interpretation of the “Verminous” Cadaver in Britain and Europe’, Church Monuments 20 (2005): 50.

12 William Page, A History of Northamptonshire, vol. 2, The Victoria History of the Counties of England (Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1906), 521.; ‘Peakirk, in Northamptonshire’, Northampton and Oakham Architectural Society 26 (February 1901): xxxix.; Rouse claims that the clerestory is 15th century, but this is impossible as he dates the wall paintings on the clerestory to the mid-14th century. Rouse, ‘St Pega’, 137. 142.

13 For the South Newington scheme see E.W. Tristram, ‘The Wall Paintings at South Newington’, The Burlington Magazine 62, no. 360 (March 1933). Conservation material and images for All Saint’s Church in Nassington can be found under E04059 in the National Wall Painting Survey, The Courtauld.

14 For the early fourteenth century a helpful example is Bruce M.S. Campbell and Ken Bartley, England on the Eve of the Black Death, An Atlas of lay lordship, land and wealth, 1300-49 (Manchester University Press, 2006), 333.

15 A particularly famous and widely circulating text is by John Mirk in the late 1380s. Theodor Erbe, Mirk’s Festial (Early English Text Society, 1905). For a version of the tale of the Warning to the Gossipers see 279.

Bibliography

Bowdler, R. ‘The Treasury of Death: The Imagery of Mortality on Cambridgeshire Monuments’. In Cambridgeshire Churches, edited by Carola Hicks. Stanford, 1997.

Bruce M.S. Campbell and Ken Bartley, England on the Eve of the Black Death, An Atlas of lay lordship, land and wealth, 1300-49. Manchester University Press, 2006.

Erbe, Theodor. Mirk’s Festial. Early English Text Society, 1905.

Gill, Miriam. ‘Late Medieval Wall Painting in England, 1330-1530’. PhD Thesis, The Courtauld Institute of Art, 2002.

Howard, Helen. Pigments of English Medieval Wall Painting. Archetype Publications, 2003.

Keyser, C.E. A List of Buildings Having Mural Decorations. Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1883.

Oosterwijk, Sophie. ‘Food for Worms – Food for Thought: The Appearance and Interpretation of the “Verminous” Cadaver in Britain and Europe’. Church Monuments 20 (2005): 40–80.

Page, William. A History of Northamptonshire. Vol. 2. The Victoria History of the Counties of England. Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1906.

‘Peakirk, in Northamptonshire’. Northampton and Oakham Architectural Society 26 (February 1901): xxxix.

Pelij, Herman. Colors Demonic & Divine: Shades of Meaning in the Middle Ages & After. Edited by Diane Webb. Columbia University Press, 2004.

Pridgeon, Ellie. ‘Researching Medieval Wall Paintings: A Guide to Archival and Unpublished Sources in England and Wales’. The Local Historian 45, no. 1 (2015).

Ross, Ellen. The Grief of God: Images of the Suffering of Jesus in Late Medieval England. Oxford University Press, 1997.

Rouse, E.Clive. ‘Wall Paintings in the Church of St Pega, Peakirk, Northamptonshire’. Archaeological Journal 110, no. 1 (1953): 135–50.

Tobit Curteis Associates. ‘Condition Survey and Proposals for the Conservation of Wall Paintings: St Nicholas’ Church, Glatton, Cambridgeshire’. n.d.

Tobit Curteis Associates. ‘Technical Examination and Proposals for the Conservation of Wall Paintings, St Pega’s Church, Peakirk, Cambridgeshire’. September 1996.

Tristram, E.W. ‘The Wall Paintings at South Newington’. The Burlington Magazine 62, no. 360 (March 1933).

Tristram, E.W. English Medieval Wall Painting: The Twelfth Century. Oxford University Press, 1944.

Tristram, E.W. English Medieval Wall Painting: The Thirteenth Century. Oxford University Press, 1950.

Tristram, E.W. English Wall Painting of the Fourteenth Century. Routledge, 1955.