Effective conservation is achieved through a process of acquiring data so that informed choices are made and implemented. This evidence-based approach implies that multiple considerations must be evaluated before conservation measures are decided and taken. We generally fail to meet these standards, however, and our history of practice is often one of failure and repeated mistakes, in which choosing remedial treatment as a default option predominates our actions.

How then should we focus our conservation aims and requirements to achieve safe and long-lasting outcomes, and do this in a context where resources of time, funding and expertise are usually limited?

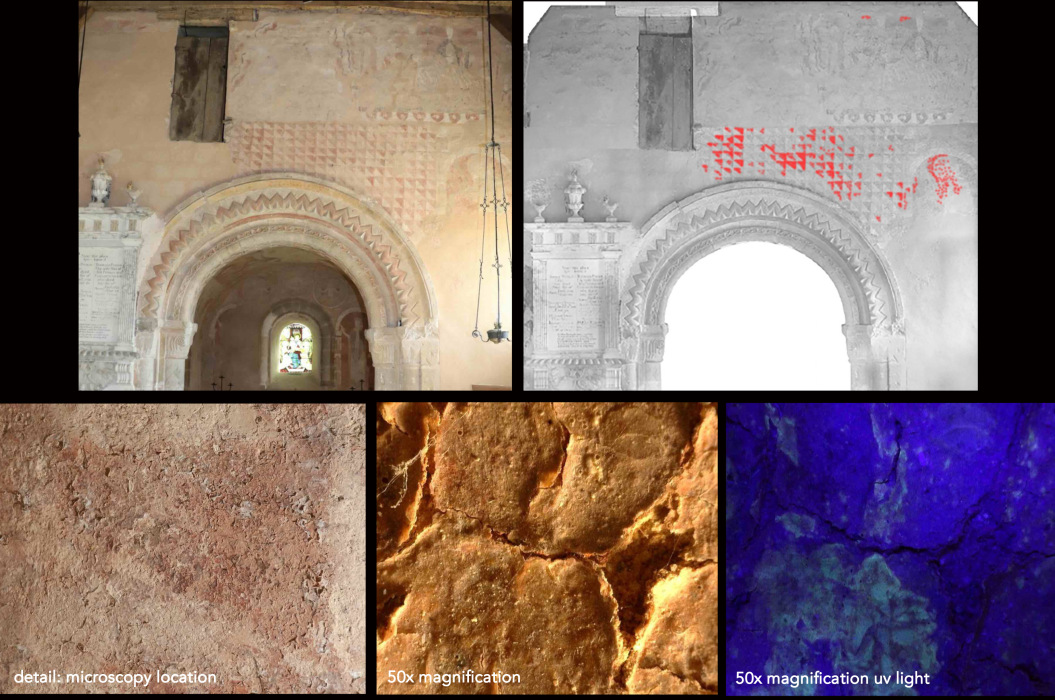

To illustrate this dilemma, we can examine approaches to one of the most common problems that adversely affect our heritage of medieval wall paintings: their coating with so-called ‘preservative’ materials, mostly applied in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. Two painted churches serve as useful examples: St Mary’s church, Kempley (Gloucestershire), justly famed for its remarkably intact scheme of Romanesque paintings of c.1130, now cared for by English Heritage (Figure 1); and the church of Little Hampden (Buckinghamshire), with scattered remains of medieval paintings dating from c.1250 and later throughout its nave (Figure 2), which is much less well known but stands as a typical survival of our ecclesiastical wall painting tradition.

If we summarise and compare their physical histories, we see that they are very similar. Their paintings were uncovered in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, a process of exposure that was usually brutal, resulting in much loss of original paint layers. Immediately afterwards, ‘preservative’ coatings were applied. In the case of Kempley, this included waterglass, egg white and shellac varnish; at Little Hampden, a wax-based formulation was used. In the mid-twentieth century, recognition of defects associated with such treatments – most seriously, the weakening and exfoliation of original plaster and painting layers due to inhibited moisture and salts movement behind the coatings – brought about a radical change in conservation practice. Between the 1950s and 1980s, efforts focused on their reduction and removal, as witnessed at both Kempley and Little Hampden.

While well motivated, these interventions were not done with the best treatment materials and procedures, and understanding of original painting technologies was poor. This is not a criticism but a statement of fact. Both the range of available cleaning materials and knowledge of their properties have increased immensely in the last half century or more, while the sophistication of original paint materials – and their vulnerability to treatment interventions – has been recognised by advances in scientific analysis.

What is the legacy of the physical histories that occurred at Kempley and Little Hampden, which are also broadly replicated at many other painted churches? A defining feature is that our medieval paintings largely exist in highly depleted states, their materiality irretrievably compromised and weakened. They are still affected by the presence of coatings, either because many paintings were never cleaned or because past cleaning attempts left residual materials behind. In short, they survive in exiguous condition and their continuing deterioration relating to added materials remains a concern (Figures 3 to 4).

Fig. 4 Detail of coated painting at Little Hampden. © Rickerby & Shekede

The recognition of the harm caused by ‘preservative’ coatings was a watershed moment in conservation practice, a rare occasion when failure was publicly acknowledged and an alternative course of action implemented. But this also created its own unwanted legacy, that coatings should always be equated with causing further deterioration and must be removed. This is a simplistic and dangerous assumption that does not stand up to scrutiny, as an examination of the circumstances at Kempley and Little Hampden demonstrates.

First, Little Hampden. Starting with the archival evidence, there is confusion as to the nature of the coating, with a SPAB report of 1908 identifying it as ‘a solution of refined size applied hot with a spray diffuser’, and an account in the Records of Buckinghamshire in 1967 stating that the paintings were ‘de-waxed’. Instrumental analysis was essential to clarify the archival ambiguity. We are grateful to Dr Joshua A. Hill, formerly of Nottingham Trent University, Department of Chemistry and Forensics, for undertaking FTIR microscopy and x-ray diffraction and identifying a bees-wax coating.

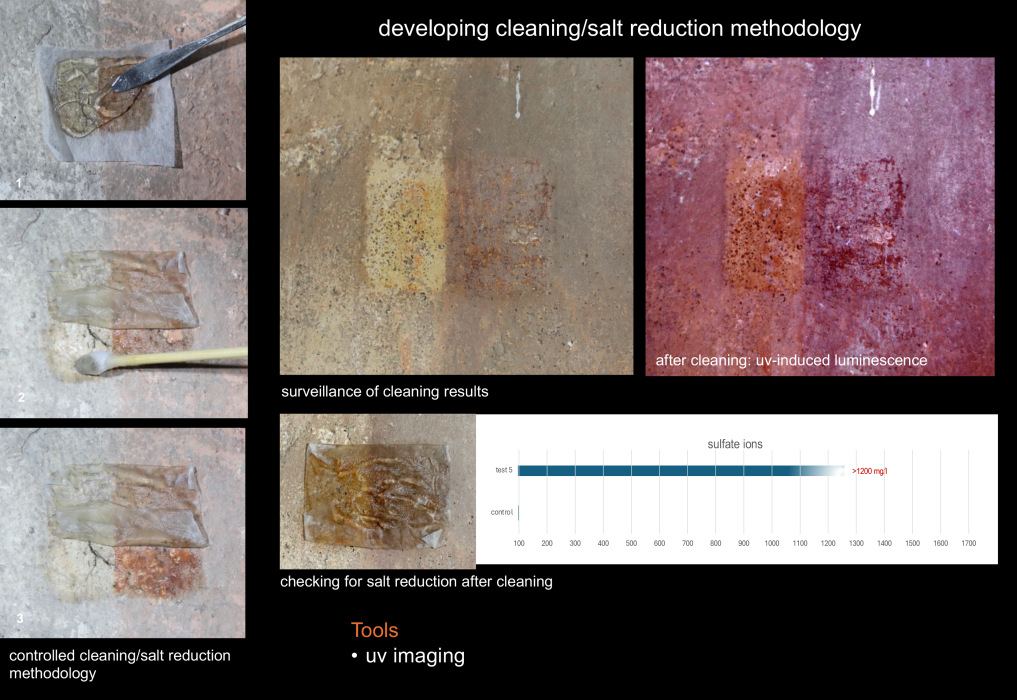

In defining conservation options, it is obviously critical to know which added materials are present, and in most cases, archival evidence will provide the answer to this. Little Hampden is a relatively rare exception where this is not so. It is just as important to characterise the physical nature of added materials and their interaction with original materials, as it is these features that usually determine whether remedial interventions are feasible and safe to undertake. We can use readily accessible and highly informative tools to do this, such as UV imaging and portable microscopy (Figure 5). At Little Hampden, these techniques reveal the coating as a thinly brushed application, now fragmented and discontinuous in its covering. It has not curled and deformed into individual flakes, and it has a grey discolouration. Knowing these features begins to enhance understanding of our ‘problem’.

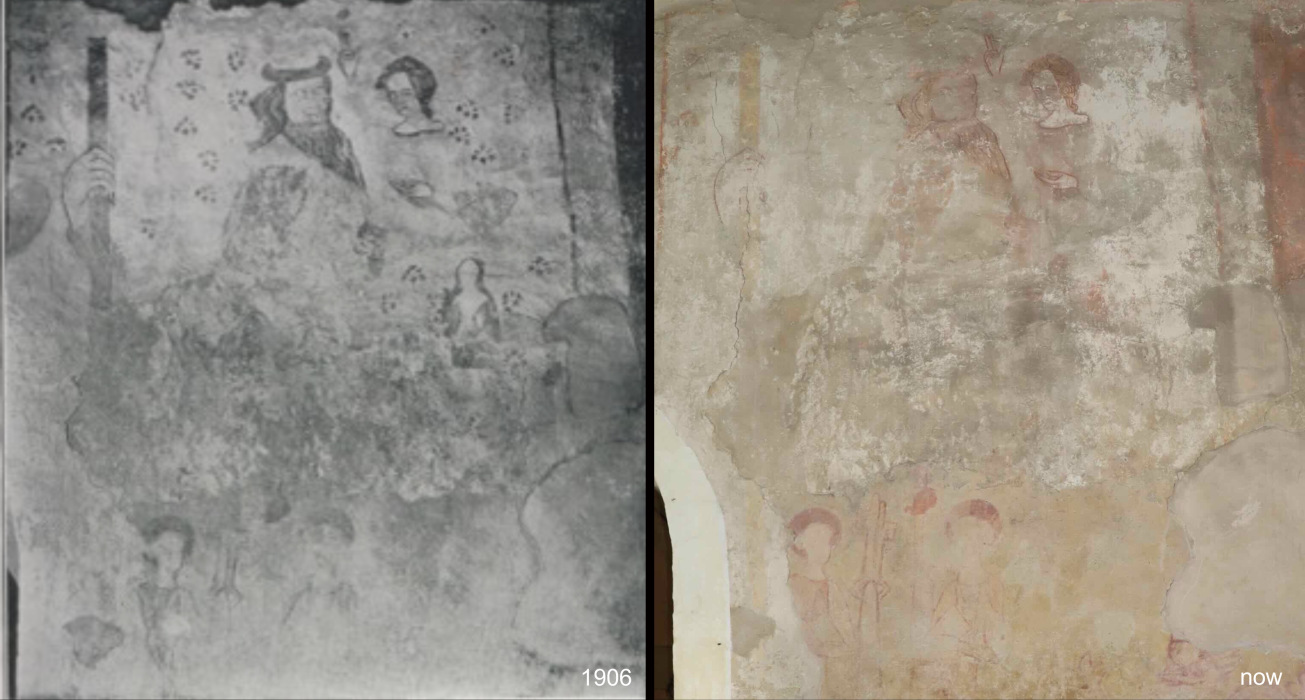

A ‘problem’ in conservation is only so if it contributes to active deterioration and paint loss. At Little Hampden, archival images provide irrefutable evidence of alarming paint loss between 1906 and the present day (Figure 6). Why is this happening? Wax coatings do not cause such problems in isolation. In common with other painted churches – though by no means all – there is salt contamination at Little Hampden, which in combination with an unstable environment promotes exfoliation of the coating, removing with it the painting. We therefore need to find out which types of salts are present, where they are – both topographically and in depth – and how they got there. We cannot define the constraints and possibilities of the available conservation options without this information.

But these are demanding questions. Understanding the nature and movement of salts in wall paintings is a specialist discipline. Identifying salt species requires scientific expertise and instrumental analysis. All this is usually unavailable to the conservator in the field. Moreover, even with the best expertise, we can never know everything there is to know about salts in a porous system. So, the question needs to be rephased: exactly how much (and which) information is required to make informed decisions? We only need sufficient knowledge to address our principal concerns well. Recognising, understanding and interpreting levels of ‘sufficient knowledge’ depends on critical judgement. But assuming that this is what a wall painting conservator should be good at – and this is a big assumption – we can generally gain an adequate understanding of the salt problems that confront us almost daily by undertaking simple testing of soluble ions and following a carefully designed sampling strategy.

To answer the question of where the salts are at Little Hampden, samples of accumulated, loose materials (dust, salt efflorescence) were collected from representative locations on the surface of the paintings. They provide information about topographic salt distribution. In addition, small core samples taken at increments to a depth of 4cms reveal the distribution of salts inside the plaster. Qualitative and semi-quantitative analysis using Quantofix® testing strips for detecting sulfate, chloride and nitrate ions tells us that our predominant ions are sulfates. Most revealingly, they are found in unusually high quantities on the surface of the painting, but they are not present within the plaster.

This crucial information helps to diagnose the nature of our salt ‘problem’: we have identified surface contamination only. The physical history suggests that the most likely source is sulfur dioxide contamination from coal- or coke-fired heating used in the early-twentieth century shortly after the paintings were uncovered. As an airborne pollutant, sulfur dioxide can be deposited and become fixed on the calcium carbonate support – either wet (as calcium sulfite) or dry – and convert to calcium sulfate (gypsum), one of the most damaging salts for wall paintings.

Having identified both the nature of our ‘problem’ and its causes, what should we do next? Environmental monitoring, another essential component in the process of focusing conservation requirements at Little Hampden, demonstrates the unstable climate conditions that drive damaging cycles of salt crystallisation and deliquescence. As the building envelope is highly permeable to frequent and rapid changes with the exterior climate, damaging fluctuations of temperature and humidity occur on the interior, which are exacerbated by intermittent heating. Measures to prevent or reduce these destabilising parameters can – and must – be implemented as our first and most effective conservation response.

What about remedial treatment: does it also have a role here? We use the findings of our investigations to address three fundamental concerns: is treatment necessary, feasible and safe? Fundamental – but surprisingly often ignored. Environmental improvements at Little Hampden will not entirely stabilise the climate activation mechanisms of deterioration. But the discovery that damaging salts are only superficially present on the painting highlights the possibility that they can be substantially removed. In combination with climate improvements, salt removal will go a long way to preventing deterioration. We next need to ascertain whether cleaning is both feasible and safe.

Treatment design is not a ‘one size fits all’ undertaking. It is also a process of defining choices and focusing aims and requirements. At Little Hampden, the discontinuous nature of the coating and its thin application, and the vulnerable nature of the original paint materials, are considerations that influence the constraints and requisites of any proposed treatment. For our specific conditions, we need a cleaning methodology that offers control and limits direct action on the exiguous painting, and because we have a problem of salts existing in combination with a wax coating, it is necessary to identify procedures that address both simultaneously. A solvent dispersed in an aqueous gel controls contact and minimises mechanical action on the painting; it also targets both the coating and the salts. As in other stages of the conservation process, we can use procedures such as UV imaging and portable microscopy as surveillance tools to assess treatment outcomes (e.g. degree of coating removal, avoidance of damage to the painting) and soluble ion analysis to check for salt reduction after cleaning (Figure 7).

Two important points emerge from the approach to ‘problem-solving’ at Little Hampden. First, although a remedial treatment component was eventually recognised, this was not a pre-determined decision; it was a judgement reached after a process of data acquisition and evaluation. Neither was it the only or most important outcome, as the success of the remedial intervention also depends on making identified environmental improvements. The issues associated with the ‘preservative’ coating in this case are not unusual – they are typical. As such, the stages of research, investigation, analysis and monitoring that were followed here should also be considered normal and expected generally.

This brings us to the second point. Aside from the instrumental analysis required to identify the wax coating at Little Hampden – which may be considered a relatively rare need – all the other stages of information gathering were carried using inexpensive, low-tech equipment: an adapted SLR digital camera and flashes to take UV images; an affordable portable microscope, able to capture astonishingly informative magnified images easily; simple test strips for detecting soluble ions; and straightforward environmental monitoring devices that do not require expensive know-how to install and maintain (Figure 8). This is not to say that higher-end technologies and outside expertise are not sometimes useful or required: they drive innovation and improve standards, which are also needed. But at most wall painting sites, our responses must be proportionate in their use of resources – of time, personnel, equipment, knowledge and expenditure.

Above all, since diagnosis of wall paintings is an integrated process of information gathering and assimilation, it is a task best determined and undertaken by the practicing conservator, the person who has – or should have – an intimate knowledge of the object and its problems. ‘Better’ forms of recording, investigation and monitoring are of little or no use if no real attempt is made to link them to the problems we are meant to solve, and it doesn’t take much for this to happen, even in the hands of some who consider themselves heritage and conservation professionals. Analysis of materials, technical imaging and environmental monitoring can easily become ends in themselves, disengaged from core conservation problems and requirements, which can remain unrecognised and unacknowledged. Our challenge is to expand and improve the remit and capabilities of the practicing conservator, rather than outsourcing untethered ‘expertise’ to others.

What about Kempley: is remedial treatment here also necessary, feasible and safe? The sequential stages of this question are intentional: if treatment is not necessary, that’s all we need to know. To convincingly answer this question, however, again involves a rigorous process of data collection and evaluation. As already described, Kempley’s wall paintings are, like Little Hampden’s, critically undermined by historic coating materials (Figure 9). But there are also marked differences in the number and type of coating materials present, their condition and interaction with original paint materials, and climate conditions. We cannot assume similar outcomes.

First, as the Kempley paintings were treated with more than one organic ‘preservative’ coating and previous attempts to remove these were not successful, materials that were once partly solubilised and then recombined are left behind. Where these altered residues remain on the paint surface, highly distorted micro-flaking has occurred. This is very different from the state of the coated painting at Little Hampden (compare Figures 3 and 4). Has the Kempley flaking substantially changed over time? The archival image base is surprisingly poor for such an important painted church, but what little comparative evidence exists suggests no or very little adverse change or paint loss in the last two decades or more. Could it be that despite the presence of the coating materials, ongoing deterioration is not really a ‘problem’?

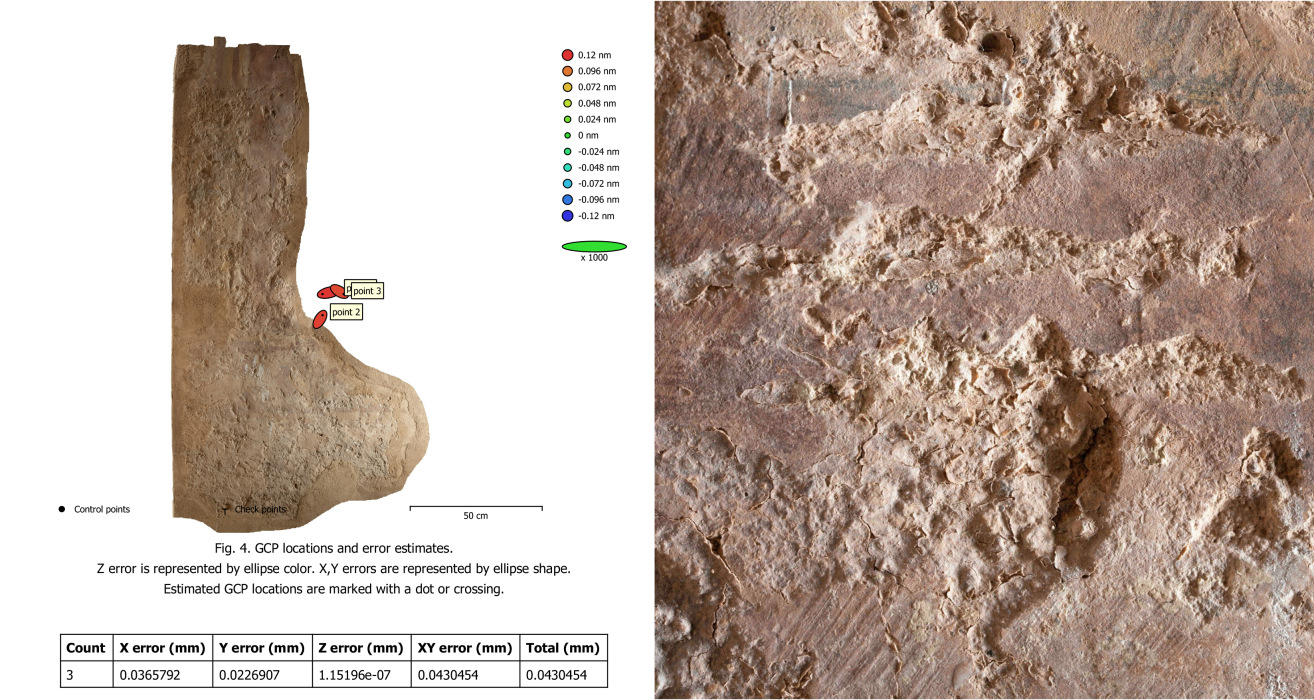

This is a critical question to answer. In an ongoing conservation programme, English Heritage has established a 3D photogrammetric monitoring base to record conditions on a micro-level – an essential undertaking – and correlate this information with environmental data (Figure 10). Some interesting early observations can be made. Kempley has a fluctuating climate not unlike other medieval church interiors, but there are significant differences and mitigating factors: it is unheated, making its climate less ‘unstable’ than most; and, very importantly, it is not contaminated by salts. In this context, the real question is not whether the climate is ‘stable’ or ‘unstable’, but whether the painting in its current compromised state can tolerate the existing climate.

The indications are that despite the residual presence of the coating materials and the alarming appearance of the flaking, the paintings have reached a point of stasis under current climate conditions. This would be a significant finding, meaning that no remedial treatment is necessary. Indeed, even if some deterioration and loss are ongoing, this must be weighed against the potentially higher risks of now trying to remove the residual coating materials from paintings in such a fragile and vulnerable condition. In this case, avoidance of physical intervention would be the best possible conservation decision.

The prospect at Kempley of leaving materials on its painting that should never have been there in the first place may seem counterproductive to the usual aims of conservation practice. It would be simpler and neater to think that coatings at Little Hampden and Kempley – and at many other painted churches – should be removed once and for all. In fact, this view – conditioned by past expectations of how wall paintings were treated – remains prevalent. To justify largescale cleaning, which is a mainstay of many private conservation practitioners, it is still easier to claim that coating materials are causing active harm, without supporting evidence. For many medieval wall paintings especially, it is routinely claimed too that they are technologically ‘simple’, with the implication that they are therefore ‘strong’ enough to withstand proposed interventions.

The examples of Little Hampden and Kempley make plain that to predetermine treatments on these grounds is both wrong and potentially dangerous. This presentation has highlighted the extremely depleted states in which many of our wall paintings survive. They cannot continue to be treated by default as they were in the past. Case-by-case diagnosis is required, to define where cleaning may not be necessary, as at Kempley; and to determine where it is needed, as at Little Hampden, as well as to define appropriate treatment parameters for the intervention and indicate other required conservation measures. If the practicing conservator is not doing this as a basic requisite, the diminishment of our already much compromised wall painting heritage will only continue, this time to a point of no return.