Today I am going to give a very brief overview of the unique collection of wall paintings in the charge of English Heritage and describe how their care has evolved over the last century, from their conservation by the earliest governmental institutions responsible for historic buildings up until the present day. English Heritage is of course the guardian of over 400 sites and monuments in England including, 79 of which contain wall paintings and associated painted decoration. Comprising a rich mixture of dates, styles, techniques and contexts, this really is a unique collection which constitutes one of our greatest little-known national treasures.

Running through the collection chronologically, by far the earliest wall painting is the remarkable and unique scheme located in a lower ground chamber known as the ‘Deep Room’ of Lullingstone Roman villa in Kent (Figure 1). The room, which was originally a cellar space, is located in the northern cross wing of the earliest iteration of the building which is dated to the first half of the first century. The painting dates to the second half of the second century, when a well was dug in the floor and one of the three original entrances to the chamber blocked by the insertion of a round-headed niche. This was plastered and decorated with an exceptionally fine and rare wall painting, originally depicting three water deities or nymphs, and the walls of the Deep Room were also rendered and decorated at the same time. The subject matter of the niche painting, the location of the villa next to a river, and the access arrangements to the room from both the interior and exterior, strongly suggest that the Deep Room was used for cultic activity during this period, probably relating to the veneration of a water deity or nymphs. Opus Conservation undertook emergency conservation works in 2022, as well as some fascinating analysis when they discovered the presence of Egyptian blue pigment.

However, by far and away the largest proportion of the collection is medieval – either monastic, secular or ecclesiastical. Firstly, there are sixteen medieval abbeys and six medieval priories in the care of English Heritage, which contain wall paintings in their living quarters, the majority of which date to the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. The paintings can vary from simple decorative designs, such as the ubiquitous masonry pattern used to decorate large spaces, to the fabulous wall paintings at Westminster Chapter House, dating to the 1380s, depicting the Last Judgement and the Apocalypse of St John (Figure 2).

Fig. 2 he elaborate painting scheme in the Chapter House of Westminster Abbey, dating to the 1380s, depicting the Last Judgement and the Apocalypse of St John. © Historic England

For wall paintings in churches, St Mary’s Church at Kempley (Glos.) contains several schemes of wall paintings including a highly important Romanesque scheme (Figure 3), while secular medieval painting is best represented by Longthorpe Tower near Peterborough (Cambs.) which is decorated with a unique fourteenth-century scheme composed of a rich combination of religious, didactic and secular subjects (Figure 4). In addition, the gatehouse at Berry Pomeroy Castle contains a stunning depiction of the Adoration of the Magi dating to about 1500, and the Agricola Tower of Chester Castle is decorated with a very rare thirteenth-century scheme. Likewise the wall painting of St George in the chapel at Farleigh Hungerford Castle (Figure 5) is another significant medieval painting which unfortunately was very heavily re-painted in the early twentieth century, but Dr Helen Howard has shown that it is composed of an incredibly sophisticated and exquisite original technique.

Moving into the seventeenth-century, post-medieval schemes are represented by Bolsover Castle which contains four schemes of wall painting which rely on theatrical yet complex iconography entirely in keeping with a building used to hosting lavish court masques and pageants (Figure 6). Also the Elizabethan cycle of paintings at Hill Hall, Essex are a unique example of high quality figurative wall painting from a period in England where very little of this calibre survives. For eighteenth-century schemes, the splendid Palladian villa of Chiswick House has interiors attributed to William Kent (Figure 7) while the interior of the Archer Pavilion at Wrest Park, built as a picturesque retreat in the baroque style, is decorated with one of two known schemes of painting by the French artist Louis Hauduroy, active c.1700 (Figure 8).

Fig. 8 The Archer Pavilion interiors at Wrest Park by Louis Hauduroy. © Historic England

Moving on to the nineteenth-century, important wall paintings survive at St Mary’s Church in Studley (North Yorks.) which contains a stunning interior by William Burges, while Osborne House is home to various very significant wall paintings including the painting executed in true fresco technique by William Dyce (Figure 9). Finally, the most modern decoration from the twentieth century includes Richmond Castle, specifically a poignant record left by prisoners of conscience imprisoned during World War I, where religious tracts, poems and drawings were pencilled onto limewashed walls of the detention cells (Figure 10). Also Hurst Castle contains a naïve but nevertheless significant theatre stage backdrop in one of the west wing batteries, a fascinating reminder of daily life for soldiers garrisoned.

So how did this extraordinary collection come about? Firstly I must mention the sources for this talk which include Barabara Bryant’s account of the Conservation Studio in Regent’s Park, ‘Stalwart Younge Men’: The First Public Picture Conservation Studio.1 Also Robert Gowing’s introduction to the conference organised by English Heritage in 1999, Conserving the Painted Past: Developing Approaches to Wall Painting Conservation,2 which outlines the early history of governmental interest in historic buildings, as does Simon Thurley’s fascinating 2013 book, Men from the Ministry: How Britain Saved Its Heritage.3

Initially, although there was some governmental support and interest in historic monuments from the nineteenth-century onwards, generally private restorers were used to attend to any necessary treatment of wall paintings. This was until the creation of the Ancient Monuments Department of the Office (later the Ministry) of Works, a government department which was effectively invented by Sir Charles Peers and Sir Frank Baines empowered by the Ancient Monuments Act of 1913 (Figure 11). This gave the state the right to intervene and acquire monuments of outstanding historic importance, thereby accumulating an astonishing national collection while overseeing state protection through the scheduling and listing of historic sites.

Sir Frank Baines, Director of Works at the Office from 1920 to 1927, was a practising architect with a scientific background who strongly asserted that the treatment of architectural surfaces required specialist skills. Baines argued for the economic benefits of an ‘in-house’ service with a more rigorous approach dependent on testing to find the most appropriate treatments.

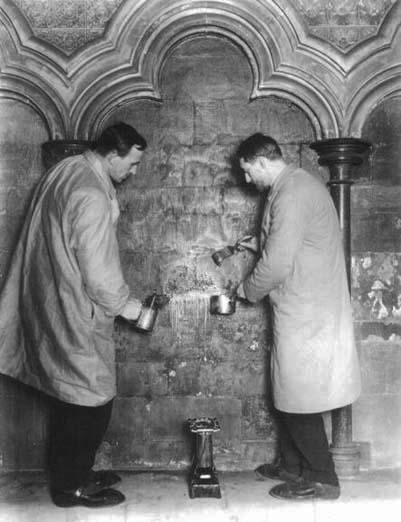

Crucially, therefore, he decided to use Office of Works staff rather than outside restorers. Originally a small unit within the Architects’ Division of the Office of Works, the studio team grew by the late 1930s to comprise six artists with fine art training, becoming known as the ‘Artist Craftsman Section’, thereby becoming the first ever dedicated, government-employed team of artist-restorers tasked with repairing, cleaning and conserving paintings primarily in royal palaces and government buildings, as well as public and historic buildings. For wall paintings, key early restoration projects included the treatment of the Chapter House scheme in Westminster Abbey.

When Baines left the Office of Works in 1927, the small team was subsequently led by James FS Jack, an architectural draughtsman who had taken over the restoration of the Leighton frescoes in 1924-5 and who went on to manage the Section for many decades. By the outbreak of World War II, Jack estimated that the team had ‘repaired, cleaned, retouched and preserved paintings to the extent of approximately 40,000 square feet of surface’.4 The artists worked either in situ, as in the case of paintings such as the magnificent paintings by Sir James Thornhill at the Old Royal Naval College in Greenwich, or in makeshift studios such as the one set up in Wren’s Orangery at Kensington Palace to work on the immense Rubens ceiling paintings from Banqueting House when they returned from their wartime storage.

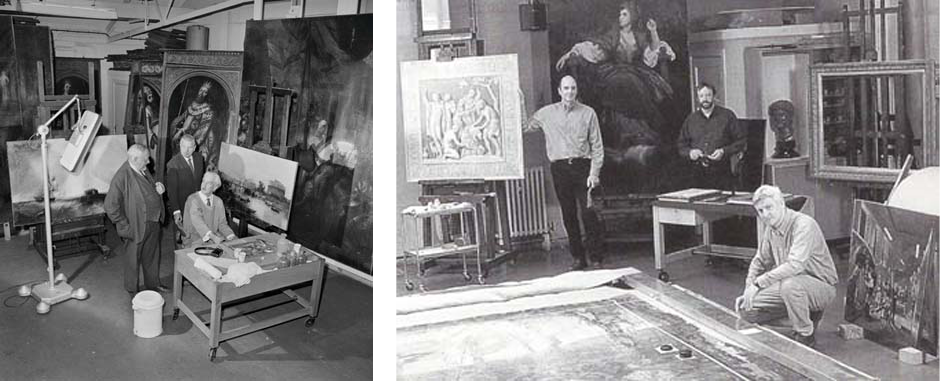

The team finally found a permanent home in 1951 – after lobbying from Jack – in the form of a Crown Estate building formerly used to retrain blinded soldiers after the First World War (Figure 12). Here the team’s work expanded to include the conservation of easel paintings from government buildings, estimated by Bryant to be then some 3000 paintings, works cared for today by English Heritage as well as Historic Royal Palaces, the Houses of Parliament, the National Trust, the Government Art Collection, Westminster Abbey, the V&A Museum and the Royal Collection. What set the Conservation Studio (as it was known) apart, however, was its specialisation in wall paintings and large-scale paintings as well as easel paintings. Notably, also, the team existed as a cohesive group well before the formation of dedicated conservation departments in the national museums.

After Jack’s retirement, Alistair Stewart became ‘Chief Restorer’ (as opposed to the previous title of ‘Artist’) in 1962, and was succeeded by Maurice Keevil in 1972 who oversaw the expansion of the Studio recruiting a younger generation. Jan Keevil, nephew of Maurice, then skilfully headed the studio from 1976 to 1993, being succeeded by Adrian Buckley who oversaw the work of the team with his customary charm and good humour (Figure 13). With the formation of English Heritage (EH) in 1983 as the government’s statutory adviser, the Studio’s areas of responsibility shifted towards the organisation’s own historic properties and advisory work on grant-aided projects. At the same time, the Studio formally acknowledged the need for distinct specialised sections for medieval wall paintings and easel paintings conservation supported by Mike Corfield, then Head of the Ancient Monuments Laboratory.

Fig.13 The English Heritage Conservation Studio in the 1990s, with Adrian Buckley, Dave Gribbin and Graeme Barraclough. © Historic England

As a result the pioneering ‘Condition Audit of wall paintings in English Heritage Properties in Care’ then followed, led by Caroline Babington and undertaken largely by Tracy Manning and Jane Davies. Completed in 1996, the individual audit reports – many of which can now be found in the National Wall Paintings Survey archive – provided invaluable information to regional teams, indicating the location and extent of the wall paintings, information on their physical history and art historical significance, and prioritising their conservation requirements using a condition scoring range from 1 (good) to 4 (unacceptable).

Change came again in late 1998, when the Wall Paintings Section became part of the Building Conservation and Research Team (BCRT). At this time it was recognised that the Condition Audit had identified the wealth of the wall painting collection and its importance as an unsung asset, leading to the ambitious plan named the ‘Year of Wall Paintings’, enthusiastically supported by the then Chairman of English Heritage, Sir Jocelyn Stevens, and led by Lloyd Grossman, the then Chairman of the Museums and Collections Advisory Committee. Our Painted Past, as it became known, was a project developed with participation from teams throughout the organisation and included the first ever travelling exhibition on wall paintings. This was shown in all nine English regions and seen by over 40,000 visitors. To accompany the exhibition, a gazetteer was produced for the wall paintings in EH properties. Finally, in 1999, EH brought together an international audience for a conference which assessed developments in wall painting conservation and evaluated strategies for the future.5

From 1999 onwards, the Section was led by Adrian Heritage, followed by Robert Gowing with assistance from Sarah Pinchin, Sophie Godfraind, Robyn Pender and Tracy Manning. However on 1 April 2015, English Heritage was divided into two parts: Historic England, which inherited the statutory and protection functions of the old organisation, and the new English Heritage Trust, a charity that would operate the historic properties, and which took on the English Heritage operating name and logo. Wall paintings stayed under the auspices of BCRT until 2016-17, after which time their care was transferred – under Sophie Godfraind – to English Heritage, and the Condition Audit once again resurrected together with an action plan developed by Amber Xavier-Rowe (Head of Collections Conservation at EH) and Rachel Turnbull (Senior Collections Conservator, Fine Arts).6 Underway since 2019, the aim is to once again assess the condition of every wall painting, the amount of change that may have occurred in the intervening period since the last audit, and to identify their conservation and treatment requirements. As of November 2024, all sites have now been inspected.

In tandem, a very successful campaign was initiated called ‘Save our Story’ which launched in September 2019 when the public were encouraged to donate to support conservation of wall paintings at four sites or “wherever the need is greatest”. This raised over £120,000 in funds. To date 84 properties with recorded wall paintings have been surveyed, of which 79 schemes are extant. As a result it is now possible to accurately identify those sites at high risk so that further investigation, emergency treatment or estate maintenance can be prioritised and the Curatorial and Estates teams advised accordingly. The ultimate aim will be to integrate future inspections into existing survey systems in order to develop a sustainable method of condition reporting. Surveys are made at each site with inspection and baseline information recorded directly on site onto a specifically designed Excel spreadsheet. This uses an innovative methodology for wall paintings combining risk and condition adapted from the same procedures developed by English Heritage for other collections.7 The Excel sheet contains immediate recommendations for further investigation, emergency treatment, or estates maintenance, as well as an indication of how long conservation input will take and a recommended priority for estates maintenance.

Then to run through some of the current wall painting projects presently underway, one in progress is at St Mary’s Church, Kempley (Glos.) (see Figure 3) where a series of interrelated investigations and recording is being undertaken by various English Heritage and Historic England specialists as well as external conservation consultants (Rickerby and Shekede) to formulate well-considered options for the highly complex long-term care of these highly important paintings.

Likewise at Berry Pomeroy Castle in Devon, a way forward is currently being sought between the Curatorial and Estates teams and Historic England with specialist in-house advice and a consultant ecologist to resolve the considerable challenges required to conserve the unique and invaluable fifteenth-century wall painting in the castle gatehouse without adversely affecting the welfare or conservation status of the highly endangered bat community and other wildlife. Interim measures to protect the painting are therefore being put in place before a more permanent solution can be implemented during the proposed Major Project at the castle in 2026/27. Once this has been shown to be successful at reducing the deposition of bat droppings on the surface of the painting, urgent remedial treatment can then proceed.

In addition a very successful project was undertaken during February and March 2023 at Longthorpe Tower in Peterborough (see Figure 4), which was a continuation of a collaborative 10-year project begin in 2019 with the Courtauld Institute to conserve the highly important scheme of fourteenth-century wall paintings. The next phase of this programme is currently underway. It is also worth noting that, since the late 1980s, there has been a formal collaborative link with The Courtauld for sponsoring student research dissertations and offering practical supervision and training on conservation projects on EH sites.

The ongoing Condition Audit has also led to significant new discoveries. For example at Goodrich Castle in Herefordshire, urgent conservation by Stephen Rickerby and Lisa Shekede to stabilise what was thought to be original but simple fourteenth-century painted decoration in the chapel led to the very important discovery of a figurative wall painting dated to c.1300. This is a very exciting discovery and although the remains are scant they indicate a once extensive figurative cycle of painting. The Audit has also highlighted those sites requiring recording to assess potential change over the long-term, and hence identify conservation requirements. For example, in Chester Castle’s Agricola Tower a geospatial survey is to be undertaken shortly which will be invaluable to assess any change in condition of the highly important scheme of thirteenth-century wall paintings. Environmental monitoring equipment is also being installed at the same time to understand the internal conditions and the impact increased visitor numbers may be having on the stability of the paintings.

Finally, understanding and raising awareness of English Heritage’s wall paintings has also been extremely important in identifying much needed research requirements. For example, a third-year MA student from the Conservation of Wall Painting Department at the Courtauld (James McGhee) is currently undertaking a very valuable investigation of the wax-based coatings which obscure the internationally important late fourteenth-century scheme of wall paintings in the Chapter House of Westminster Abbey (Figure 14). The potential conservation of these paintings is much needed, but exceedingly complex, and this initial research is an important start in establishing options for their long-term care. Thus the Condition Audit is proving to be extremely successful on many levels. Not only is this unique collection being re-recorded in order to establish their condition and immediate conservation requirements, but the exercise is also proving crucial in alerting the Curatorial and Estates teams to the presence of wall paintings in sites under their care, so that their future inspection can be embedded into existing survey systems.

1 Bryant, Barbara, ‘Stalwart Younge Men’: The First Public Picture Conservation Studio’, Collections Review, English Heritage, Vol.3 (2001): 128-137.

2 Gowing, Robert, ‘Developments in wall painting conservation within the UK’, Conserving the Painted Past: Developing Approaches to Wall Painting Conservation (Post-prints of a conference organised by English Heritage, London 2-4 December 1999), English Heritage (2003): ix-xiii.

3 Thurley, Simon, Men from the Ministry: How Britain Saved Its Heritage, London and New Haven 2013.

4 Bryant, “Stalwart Younge Men”, 131.

5 Proceedings of the conference were published as R. Gowing, and A. Heritage, eds., Conserving the Painted Past: Developing Approaches to Wall Painting Conservation (Post-prints of a conference organised by English Heritage, London 2-4 December 1999) (English Heritage, 2003).

6 With help from Helena Cave-Penney (EH Senior Survey Coordinator), Karen Gwilliams (Team Leader, Historic Building Surveyor), Sybilla Tringham (Programme Director, Courtauld Institute of Art, Conservation of Wall Painting Department), and Paul Lankester (EH Conservation Scientist).

7 See https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/siteassets/home/learn/conservation/collections-advice–guidance/heritage_collections_at_risk.pdf, accessed 05/03/25.

Bibliography

Bryant, Barbara, ‘Stalwart Younge Men’: The First Public Picture Conservation Studio’, Collections Review, English Heritage, Vol.3 (2001): 128-137.

Gowing, Robert, ‘Developments in wall painting conservation within the UK’, Conserving the Painted Past: Developing Approaches to Wall Painting Conservation (Post-prints of a conference organised by English Heritage, London 2-4 December 1999), English Heritage (2003): ix-xiii.

Gowing, R., and A. Heritage, eds. Conserving the Painted Past: Developing Approaches to Wall Painting Conservation (Post-prints of a conference organised by English Heritage, London 2-4 December 1999). English Heritage, 2003.

Thurley, Simon, Men from the Ministry: How Britain Saved Its Heritage, London and New Haven 2013.