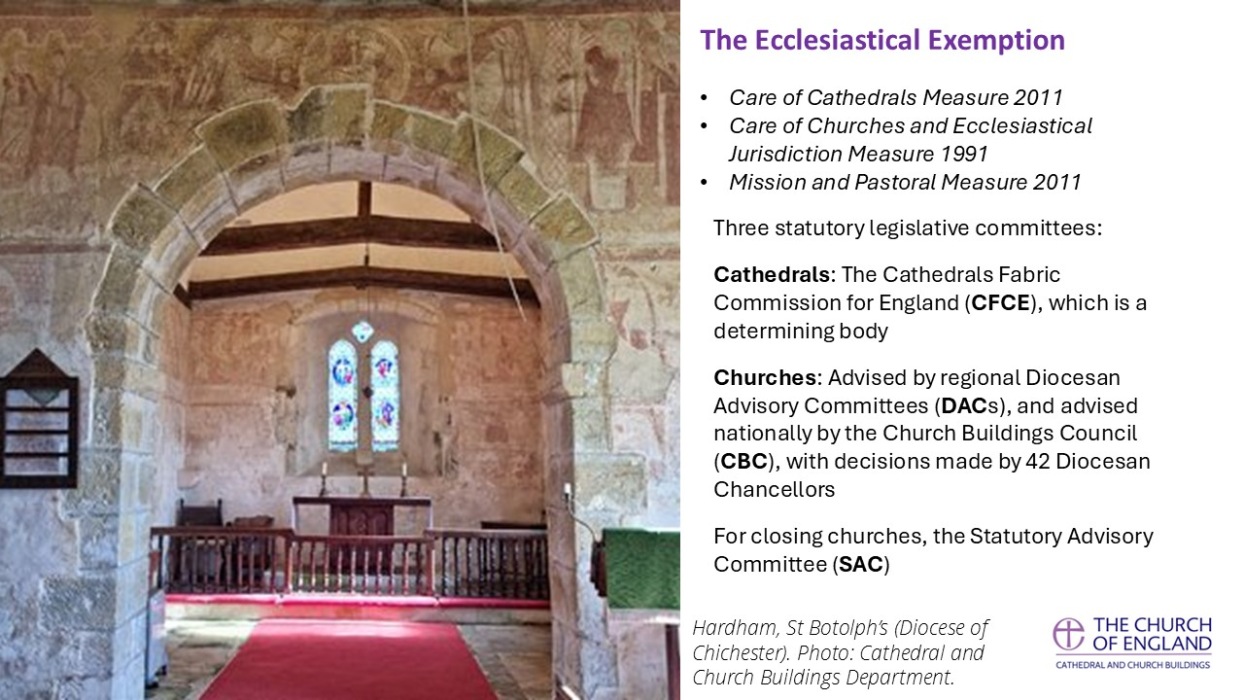

Chances are, if you are a wall painting conservator, you’ve spent a lot of time in churches. And when talking about the conservation of anything in churches, it invariably turns to following rules. I don’t want to bore you with the ins and outs of the Ecclesiastical Exemption and the Faculty Jurisdiction system, but it’s important to understand them, because it shows the special status that places of worship have.

The care of cathedrals and churches are governed by various legal frameworks, including the Care of Cathedrals Measure, the Care of Churches and Ecclesiastical Jurisdiction Measure and the Mission and Pastoral Measure. This means that they are exempt from the usual listed building consent requirements, but they are not exempt from planning permission.

The whole reason that churches have their own planning system is because any change to them, including conservation, needs to be looked at not only from a heritage or conservation perspective, but also from the perspective of those who use the buildings as a place of worship. The statutory committees listed here all advise on casework, policy and best practice.

This is a very big subject, so I’ve decided not to talk about the system for cathedrals, which works differently to parish churches, in that the CFCE is a determining body that grants permission for work; nor will I speak about the process for closing churches. With changes to open churches, decisions are made by regional chancellors, advised by their Diocesan Advisory Committees (or DACs), the Church Buildings Council and other statutory consultees.

The Church of England cares for nearly 16,000 churches in England, over 12,500 of which are listed. In fact, 45% of all Grade I-listed buildings are churches. This is a screenshot of the interactive parish map available on our website, and the red and orange dots indicate Grade I and Grade II* listed church buildings. Each church is run independently by a Parochial Church Council (PCC) and churchwardens, who are a group of volunteers entrusted with their care.

As we have heard from Emily in her talk, 70% of the Survey relates to churches. So just by those numbers alone, you can see that the conservation of wall paintings in Church of England churches is critical to the field as a whole in this country. Understanding where they are, their history, subject matter, the history of their past treatment, all informs how we care for these paintings. And the Survey provides a valuable first step in that process.

Wall paintings continue to be discovered in churches. Once they are discovered, that whole process, from discovery, to understanding, and ultimately to treatment, needs the input of a wide range of people along the way. Any one wall painting project can involve clergy, churchwardens, architects, surveyors, structural engineers and art historians, as well as experts in fundraising, interpretation, and outreach. And of course, conservators. But before any treatment can be considered, faculty permission is required.

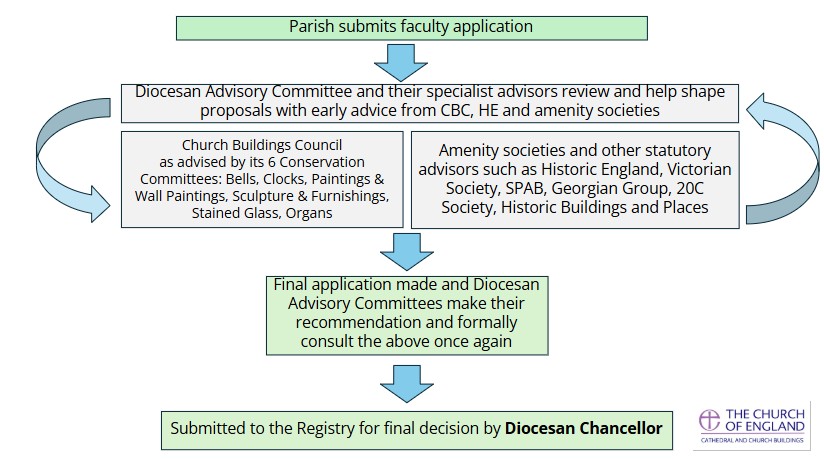

This diagram provides a brief overview of how the faculty permission process works. When the parish makes an application they often don’t have any specialist input or advice in doing that. They might be worried about the appearance of the painting, or they might want to make a change to the building where a wall painting is located. Whatever has spurred the decision, they usually start by getting advice from their architect and then their DAC, who usually recommend that they get a report by a conservator.

After that point the system dictates that advice should be sought, and that begins the process of discussion and hopefully fine-tuning the proposals so that, at the very least, the Chancellor, who is going to make the final decision, has enough information in front of them to make that decision to allow the work to go ahead, and if so, whether they think there should be any conditions. It’s very important to remember, also, that without permission in place, contractors can be liable and taken to court. This rarely happens but is worth bearing in mind.

So what I really want to get across here is that this whole process is an opportunity to pause, and look carefully at the whole project, and decide whether the right questions are being asked – things like: what is the significance of the wall painting scheme, how has it been treated in the past, what has been added to it, what is the condition of the building, and is it actively deteriorating? Do we know enough about that process, and what else do we need to know to be able to decide whether treatment is necessary or appropriate? Ultimately, how can we slow down that cycle of treatment and focus on understanding the root causes of what we are seeing?

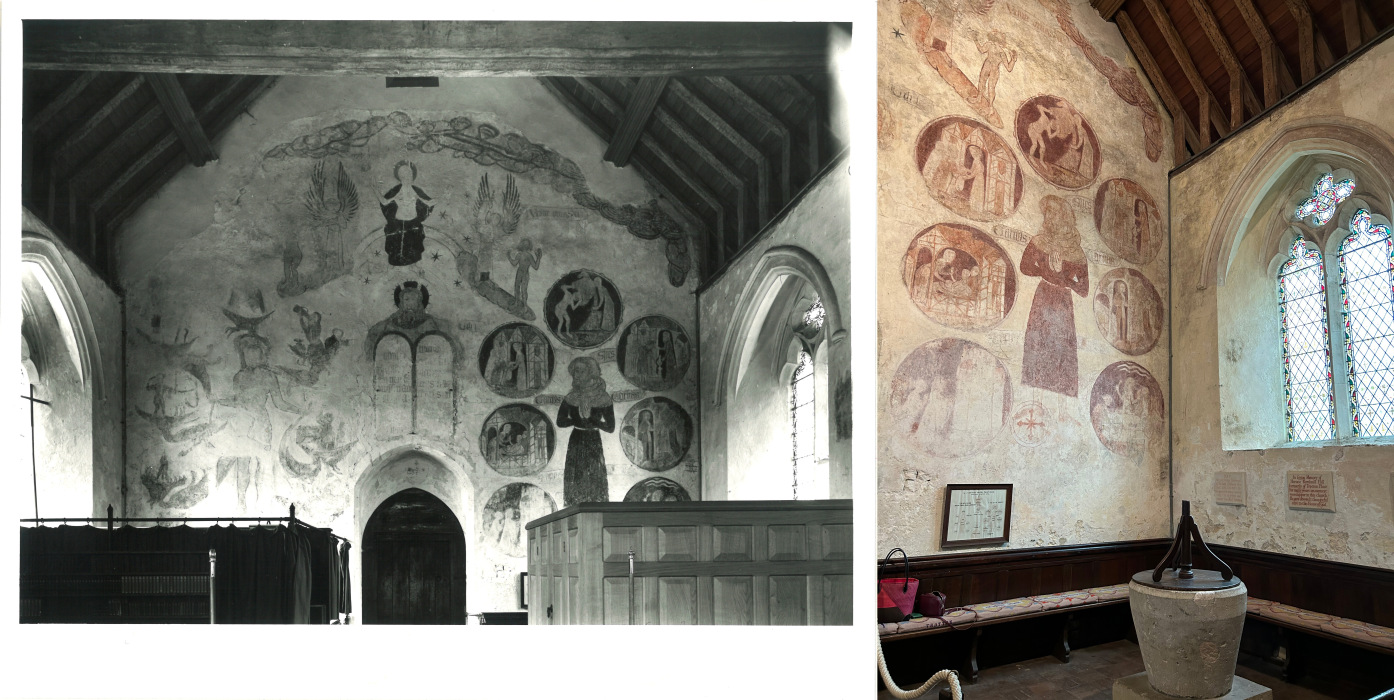

Fig. 5 (right) A more recent image of the paintings in St George’s, Trotton (Diocese of Chichester). Photo: author's own.

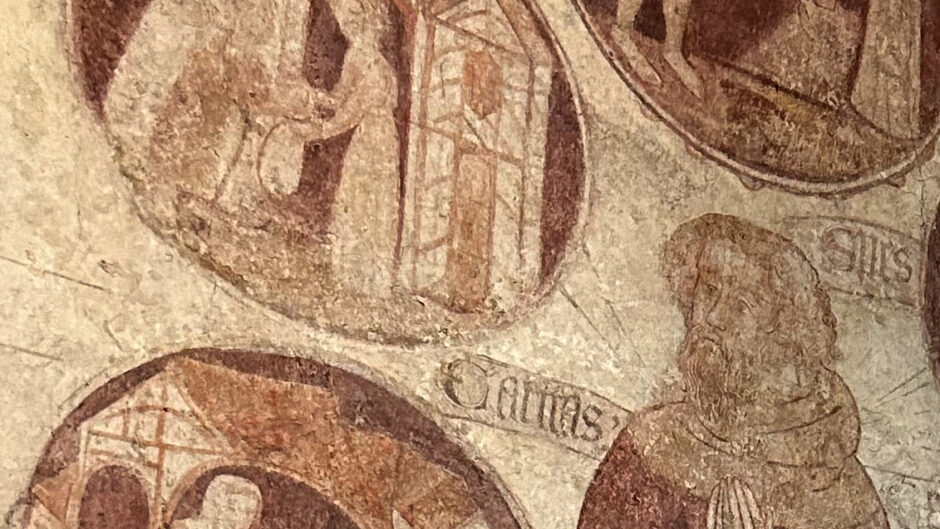

So what types of applications do we see the most often? I’ll quickly run through a few examples of the type of things we see on a regular basis. Conservation might be spurred by the parish observing that something about the wall paintings has changed, as was the case at Trotton here. They felt that during lockdown, when the church was closed, the paintings became clearer, and then when they reopened, the paintings had faded. The black and white image on the left is from the Survey archive, taken in the 1960s; the image on the right is from a recent visit. It goes without saying that early photography like this is an incredibly useful resource for assessing deterioration.

Applications might relate to changes that are happening in and around the wall painting. For example, more and more we are seeing changes to heating. As the Church drives towards achieving Net Zero in 2030, many churches are changing or updating their heating systems to be carbon neutral – which is a good thing, but we have to look at how these changes may or may not affect wall paintings. At this church near Bristol, we were able to access old photographs from the Survey of the fourteenth-century wall painting, and notes from the Tristram archive. This is good example of how it is possible to consult the Survey to help understand what wall paintings exist in the area affected. The proposal here was for heated chandeliers – this is a live case, so nothing has been approved yet.

Other things that might affect wall paintings are changes in use of the area around them. Recently, for example, at St Michael’s Church, Stanton (Glos.), the parish wished to convert a vestry area where there are the remains of fourteenth-century wall paintings, into a kitchen and servery. Again, the Survey was really useful here because we could access Tristram’s notes on the paintings, and two conservation reports carried out in the last thirty years, all of which helped inform decision-making as the project developed.

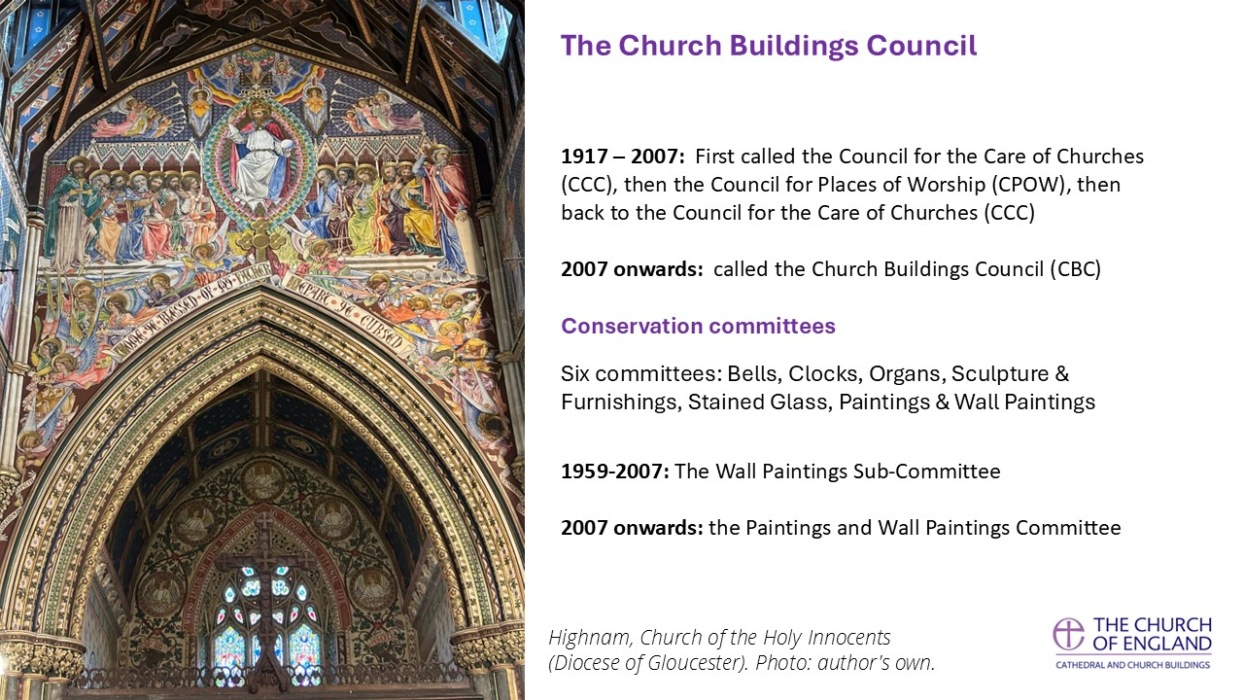

It is worth looking a bit more closely at the Church Buildings Council’s specialist committees, particularly its Wall Painting Committee. When you see CCC (Council for the Care of Churches) and the CBC (Church Buildings Council) they are both the same thing: over the years the name has changed and changed back again several times, but it is the same body. It is advised by several conservation committees, made up of volunteers who are specialists in their respective fields.

The Wall Paintings Sub-Committee was set up in 1959. David Park, who had already taken on the Survey, joined the committee in the late 1970s, and regularly reported progress on the Survey to the committee. The committee were interested in progress, because it had obtained outside funding from the Pilgrim Trust for conservation work, so wall paintings that were identified in the Survey to be at particular risk were then considered by the committee for funding.

What I’m trying to get across is that the findings from the Survey actively fed into the official channels and processes of the CCC in order to fund wall painting conservation, but at the same time, the committee began to discuss the establishment of a training programme for wall painting conservators. This collaboration, helped by the funding, managed to change the landscape of wall painting conservation in this country, as during the 1980s more freelance wall painting conservators established businesses here. The Courtauld training course began in 1985 and the UKIC (now Icon) Wall Painting Group started in 1984.

Since then, the field has evolved and grown, but we can always do more. There could, and should, be many different routes into wall painting conservation, and we need to continue to welcome and encourage collaboration if the field is to continue to grow.

Wall paintings are unique because they are in, and belong in, living buildings used by people. All of these rules and processes are essentially there to support the people who are the custodians of our wall paintings, so that they can continue to use their churches for the purpose they were meant for, and to allow them to adapt their buildings – within reason – to continue doing that.

So I wanted to end with a reminder of who we really want to reach with our work. Take, for example, the churchwarden at Trotton church. She writes grant applications, fundraises, and keeps the church running. She does that because she has been entrusted with the care of the building and she is trying to do the best job that she can. We rely on people like her to open and close the church, keep an eye on condition, and alert specialists when help is needed. She needs access to good advice, and she needs our help to get that advice.

This is a very brief summary of how we work. I do hope that you will think about becoming part of our system by lending your own voice to the Church’s advisory committees all over the country.