The cardinal importance of the Bank of Ireland (formerly the Parliament House) in Dublin to the architectural history of Ireland and Britain is incontrovertible. In its function as Parliament House, it was saturated with potent historic, political and symbolic meanings. The institutions which inhabited it both fashioned and were fashioned by these meanings.

There has, however, been a disconnection in recent scholarship from the iconographic and symbolic meanings which were attached to the building in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. As a result, its conversion to a bank after 1802 has been popularly misunderstood as an aberration, and the Bank’s architectural works have been cast as sacrilegious acts of vandalism. Utilising an iconographic methodology, an analysis of the visual self-fashioning of the Parliament and later the Bank in fact reveals that they both sought to fashion perceptions of their respective functions and ideological aims in a manner which led to the two institutions being perceived as parallel and interdependent. Thus, when the Parliament was abolished in 1800, the Bank could adopt and restore its former home as an act of continuity which rehabilitated the building after the damaging political upheaval which preceded the Act of Union.

Introduction

The Bank of Ireland on College Green in Dublin is a building of immeasurable importance to the history of architecture in Ireland and Britain. Commenced in 1729, it was the first building in the world purpose built to house a bicameral legislature. It acted as home to the Irish Parliament until its abolition in 1800, after which it was converted for use as the headquarters of the Bank of Ireland. Yet despite its historic, architectural, iconographic and political importance, it has not been given the academic exploration it perhaps deserves.[1] Furthermore, very little has been written on the development of the building after its conversion to a bank in 1802. The conversion has been popularly cast as an aberration and the Bank’s works as acts of architectural vandalism which could only be undone by a full restoration of the building to legislative use.[2] As late as 1920, legislative measures were put in place for the summary eviction of the Bank and its replacement with the Parliament of Saorstát Éireann.[3] This was very far from the attitude of early nineteenth-century commentators: to them, occupation by the Bank was an act of continuity. The building may be reconnected to these perceptions through an aesthetic analysis of its history which explores how the institutions which inhabited it both shaped, and were shaped by, symbolic and iconographic messages contained in its plan, materials, decoration and use.

There has been much interest among historians and anthropologists alike in relating social, cultural and political patterns of behaviour to the built environment.[4] Writing on parliament buildings, Sean Kelsey has argued that ‘claims to authority, legitimacy and distinction have been articulated and contested through the construction, control and adornment of the very fabric of buildings in which culture is shaped and expressed, governance conducted and governments made and unmade’.[5] This topological dimension to questions of legitimacy, power and prestige is one particularly pertinent to the examination of the Bank of Ireland building. Edward McParland has argued that ‘buildings are important advertisements… and they are open affirmations of how the patron wishes to be seen by the rest of the world’.[6] Similarly, in his exploration of the symbolic infrastructure of Protestant Dublin, Robin Usher has written of how ‘early-modern societies conceived of their surroundings as a web of symbols that aided their understanding of their institutions, belief systems and their physical environment’.[7]

In the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the Parliament and the Bank were both dominated by prosperous Protestants drawn mainly from the mercantile and professional classes, and neither institution was at all representative of the majority Catholic population.[8] According to David Hayton, what united this class was ‘a set of political principles that were recognisably “Whiggish”, comprising the preservation of the powers of parliament and the liberties of the subject; the rejection of administrative corruption; concern for the prosperity of Ireland; and fear of the revival of Catholic power’.[9] Proponents of these principles moved for strong self-government and framed relations with Britain as a necessary marriage of convenience which could be the source of mercantile competition or legislative antagonism. As Henry Grattan stated ‘you can get a King anywhere…but England is the only country with whom you can participate in a free constitution. This makes England your natural connexion and her King as your natural as well as your legal sovereign’.[10] This ideology has, not without criticism, been deemed ‘Irish Whiggism’.[11] This terminology is perhaps not as useful as it first appears. Whilst broadly reflecting the collective beliefs of the majority of this Protestant class, the weight which individual members placed on each of these principles varied considerably. Thus, in this article, the term ‘Irish patriotic project’ signifies the concerns the majority of its proponents could agree upon, namely the promotion of Irish commercial trade, the discouragement of absentee landlordism and the strong Irish self-government required to achieve these aims in the face of English mercantile competition.

‘First in the eye of all Strangers’: The Construction of the Parliament House, 1729-1739

On 10 January 1728, a Committee of the Irish House of Commons charged with examining the physical degradation of Chichester House, the then home of the Irish Parliament, stated that ‘it seems absolutely necessary to build a New House’.[12] The timing could hardly have been less fortuitous. Between 1726 and 1728, Ireland had suffered a series of crop failures which had devastated the economy.[13] Furthermore, this was a mere seven years after the passing of the Declaratory Act in which it was declared that ‘the Kingdom of Ireland hath been, and of right ought to be subordinate unto and dependent upon the Imperial Crown of Great Britain’, thus humiliating the Irish parliament by severely restricting its legislative jurisdiction and abolishing the judicial appellate jurisdiction of the Irish House of Lords.[14] Yet the building they commenced in 1728 was one of the most effective exercises in self-fashioning through architecture ever seen in Ireland. The Parliament House became both the physical manifestation of the Parliament’s authority and legitimacy, and a symbolic nexus for the patriotic project it instigated.

When the Building Committee first met, Thomas Burgh, as Surveyor General of Ireland, may well have expected the architectural commission.[15] To the majority of the Committee, however, Burgh’s work was indelibly tainted with the shady politics, corrupt patronage and pro-English stance of the British administration at Dublin Castle from whence the great majority of his architectural commissions had come and to which he owed his livelihood and reputation. The majority of the Committee clearly wished to capitalise on the iconographic potential presented by adopting a distinctive architecture at the Parliament House which would make it visually, as well as ideologically, distinct from the Castle. The Committee thus turned to another of their own number, Captain Edward Lovett Pearce, to prepare plans. Pearce operated within a close-knit network of notable politicians, clerics and architects, deemed by Robert Molesworth to be the ‘new junta for architecture’, who sought to promote the Irish patriotic project through high-profile building projects which would act as redemptive economic stimuli through the process of construction and the encouragement of settlement, and which would, as cultural objects, demonstrate Ireland’s increasing self-confidence and independence from Britain.[16] The House of Commons submitted Pearce’s plans to the Lord Lieutenant in April 1728.[17] In order to avoid the difficulty that, in overlooking Burgh, the King’s appointed Surveyor, Parliament had, in effect, usurped the Royal Prerogative, the Lord Lieutenant also obtained plans from Burgh and submitted both to the King with a clear recommendation that Pearce’s plans be approved.[18] A cousin of Sir John Vanbrugh and well-connected in both English and Irish Whig circles, Pearce spent time in Italy in 1723 and 1724 studying Vitruvius and Palladio.[19] He had been carrying out work for the Speaker of the Irish Commons, William Conolly, on his mansion at Castletown, Co. Kildare since at least 1722 and was elected M.P. for Ratoath on 21 February 1728.[20] The foundation stone of the new Parliament building was laid on 3 February 1729.[21] At scarcely thirty years old and with no major architectural commission to his name complete, his selection by the Committee was, as McParland has commented, an unprecedented act of faith representing “a radical new departure for public architecture in Ireland”.[22]

In his memorandum on the building, Pearce wrote that the building would be ‘first in the eye of all strangers at their landing’ and therefore its iconography and message would have to be patent and assertive.[23] On the exterior, Pearce adopted a decoratively stripped-back rationalism which is unique to Ireland. With its gargantuan pair of open Ionic colonnades terminating in pedimented pavilions and centred on a tetrastyle portico, no other building in the British Isles looked quite like it. While a sense of antiquity had become synonymous with the articulation of authority in European architecture generally by this period, in Dublin the iconographic meanings ascribed to this form of classicism ran deeper.[24] This rational, learned, uniquely Irish stripped back classicism seemed to reflect the ideals of civic virtue derived from Cicero which underpinned the Irish patriotic ideal of government.[25] As such, it was a particularly highly-charged choice for the Parliament House, infusing the institutions which inhabited it with ideals of good government, ancient liberty and prosperous stability.

The physical location of the Parliament House was vitally important in the development of the public perception of the institutions which inhabited it. Together with the seat of Protestant learning in Ireland, Trinity College – where a Catholic episcopal ban on attendance was not formally lifted until 1970 – the Parliament House formed a symbolic and physical boundary to one of the most important civic spaces in Dublin: College Green (Fig. 1). Grinling Gibbons’ 1701 statue of William III in the garb of a Roman emperor, to which an annual civic procession was made on the King’s birthday, formed the epicentre of this space. On the base of the statue, William was hailed as ‘preserver of religion, restorer of laws, upholder of liberty’.[26] Centred on the statue and dominated by the Parliament House, College Green became a politically charged space and a nexus for protest. On 3rd December 1759, for instance, protests against a rumoured move in the Castle for parliamentary union with Britain became focused on the Parliament House. An assembled mob of about 3,000 persons marched to the building and took control of the Commons and Lords.[27] Horace Walpole reported a litany of physical abuses inflicted upon the members of both Houses as they attempted to gain entry or escape the mob and that in the House of Lords, they “committed the grossest and most filthy indecencies” and placed an old woman on the Throne, providing her with tobacco and a pipe, before proceeding to the Commons where they demanded the Clerk to bring them the Journals to burn.[28] Furthermore, during the Civic Parade marking the birthday of William III on 4 November 1779, one thousand Irish Volunteers marched to the Parliament House to salute the statue of the monarch armed with cannon and placards inscribed ‘Free Trade! – or this’.[29]

The physical location of the Parliament House, in combination with its utterly distinctive appearance, provided a sharp contrast to Dublin Castle. The Castle had been destroyed by fire in 1684 and was rebuilt in a haphazard manner over the next eighty years. As a result, its brick structures lacked grandeur and architectural coherence.[30] Furthermore, in contrast to the open arms of the Parliament House facing directly onto College Green, the Castle was entirely barricaded from view by its surrounding buildings (Fig. 2). This contrast expressed the symbolic ‘otherness’ of the new Parliament House and, by implication, its rejection of the politics of the Castle. This understanding of the two buildings fundamentally influenced later perception of the institutions which inhabited them. In his biting satire of the 1753 Money Bill crisis, A Fragment of the History of Patrick, the satirist Henry Brooke cast Dublin Castle as ‘Mountformal’, a house ‘in which there was much state and little business’ in contrast to the Parliament House wherein ‘most of Patrick’s [Ireland’s] business was transacted’ and ‘all the servants of it were chosen by Patrick’s children’. The Parliament House was, we are told, ‘more peculiarly Patrick’s house than any other’.[31]

Pearce’s plan demonstrates clearly where power lay in the Irish patriotic paradigm (Fig. 3). The axes and symmetries of the single storey building are determined by the location of the dominant octagon of the Commons Chamber. In addition to being much smaller than the Commons, the Lords was set off axis to the east in a position of distinctly secondary importance. The physical marginalisation of the Lords on the plan provides a telling contrast with the plan of Chichester House, where the chambers were axially aligned and of equal size. In one early proposal,[32] it seems that Pearce originally intended to replicate this pattern with the two equally-sized chambers having equal entrances. The spirit of these equal entrances survived in Pearce’s terminating pedimented pavilions in the south elevation as designed, but the dominance of the dome marking the Commons on the elevation as built (despite Pearce’s assertion that the dome ‘stands so far behind that none at all or very little of it can be seen’), and the fact that the Commons opened directly onto the central axis under the main portico undid much of this egalitarian design (Fig. 1).[33] Whilst Pearce explained the disparity in his Memorandum on the plan in terms of practicality – the Commons had to seat 300 members, the Lords at most thirty – it is easy to suspect that Conolly was at Pearce’s elbow when the decision was made to marginalise the Lords as a physical manifestation of where the power lay in the patriotic paradigm.[34]

The question of materials is also key to understanding the contemporary perception of the Parliament House. The advancement of Irish prosperity through the promotion of Irish manufactures and independent free trade was a key aim of the Irish patriotic project. Pearce himself had patriotically recommended the use of Kilkenny marble in the construction of the House of Lords as ‘equal in goodness and Beauty to any forreign Marble and the Produce of the Kingdom’.[35] The carved marble and oak Lords’ chimneypiece was commissioned from Thomas Oldman of Dublin, whilst the great Lords’ chandelier was produced in 1788 by Chebsey’s Glasshouse at Ballybough Bridge.[36] When the building was completed in 1739, Robert Howard, Bishop of Elphin wrote that it was ‘indeed too fine for us’ but it had ‘chiefly employed our own hands’.[37] The clearest manifestations of this concern to promote Irish industry were the pair of tapestries commissioned for the House of Lords.[38] In 1727, Robert Baillie, a Dublin upholsterer, petitioned the Irish Parliament, complaining that ‘considerable sums are being spent on bringing tapestry from London, Brussels or Flanders at great expense’ when there were ‘exceeding good tapestry weavers’ in Dublin.[39] Baillie, ‘emboldened from the encouragement this most Honorable House has always given to the manufacturers of this Kingdom’, suggested that it would be appropriate to perpetuate the memory of the Glorious Revolution at the Parliament House in six tapestries depicting scenes from William III’s Irish campaign. These events, he argued ‘will be as suitable for the House of Lords in Ireland as the Defeat of the Spanish Armada is for that of Great Britain’ and the commission would, he declared, ‘prevent the money from going abroad’.[40] Six tapestries were ordered in May 1728, though in the end only two were produced.[41] The first, The Glorious Battle of the Boyne, depicts the battle of 1 July 1690 as the turning point in William’s Irish campaign, which secured the Protestant succession and Glorious Revolution settlement. The second, The Glorious Defense of the City of Londonderry, depicts the largely Protestant city under siege by the Jacobite Army in 1689. The iconographic message was clear: the Glorious Revolution had saved Ireland from the tyranny of absolute monarchy and the Parliament House was the embodiment of the rights and liberties it had secured.

‘Where Erin’s Independence Grew and Died’: The Architectural Development of the Parliament House and the Unravelling of the Irish Patriotic Project 1779-1801

The Parliament House survived entirely unaltered as an effective and powerful iconographic symbol of the legitimacy and patriotic ideological aims of the Irish Parliament for over fifty years. However, with Irish free trade secured in the reform of the Navigation Acts in 1779 and the repeal of the Declaratory Act under the 1782 Constitution, several modifications were made to the building to adapt it to the needs of an increasingly active, though politically splintering, Parliament.[42] Hailed as the crowning achievement of the Irish patriotic project, the 1782 Constitution had been effectively secured in opposition.[43] Once in place, however, old ideological fault lines became apparent, particularly when it came to questions of political ties with Britain and Catholic enfranchisement on which promoters of the Irish patriotic project were bitterly opposed. As a result, the Irish Parliament’s effectiveness and perceived integrity were gradually eroded as the British administration took advantage of political infighting. Whilst the primary motivation for the post-1782 modifications may have been one of practicality, the modifications were thus both propagandised and perceived as physical manifestations of the degradation of the Irish Parliament itself.

With their judicial function restored under the Constitution, the Lords immediately required increased accommodation within the Parliament House. Lands to the east of Pearce’s colonnade were purchased, and in June 1782, James Gandon was approached to provide plans for offices and a new entrance on Westmoreland Street. Unlike Pearce, Gandon was English and he had been brought to Ireland to work for the Castle administration.[44] The Lords’ choice of an English architect who was under the patronage of the Castle is perhaps a telling contrast to the Commons’ shunning of Burgh in 1728, though Gandon, who had declared Pearce’s south front to be ‘chief amongst the public buildings’ of Dublin, initially showed himself to be acutely sensitive to preserving Pearce’s work.[45] Two schemes (Fig. 6) maintain Pearce’s Ionic Order and show straight walls stepped back to meet Pearce’s existing south front with an astylar archway.[46] However, because of the falling gradient of the street, an Ionic portico to the east would have ‘been ascended by a considerable flight of steps, or its grandeur would have been totally marred by the high pedestals required for the columns’.[47] Gandon’s solution was to abandon the Ionic Order in favour of a hexastyle portico composed of the taller columns of the Corinthian Order, which absorb the gradient of the ground (Fig. 4). He connected the portico to Pearce’s south front by means of a curved unbalustraded screen wall and, to prevent a clash of Orders where the two façades met, he avoided the use of any specific Order on the wall. The choice of the Corinthian Order for the Lords entrance may have been dictated by practicality, but for the Lords, it was one which could be propagandised. The Corinthian Order held architectural superiority over the Ionic Order used at the Commons’ entrance and this symbolic hierarchy was later popularly perceived to be a deliberate symbolic statement on the part of the Lords.[48] Such propagandising was perhaps unsurprising from a House previously marginalised both physically and symbolically in the building. Architecturally, however, the tacking of a Corinthian portico onto the side of an Ionic building was subject to much criticism. In his 1805 annotated poem, The Metropolis, William Norcott lamented that in adopting two Orders, the Houses had ‘raised a monument of their own folly’.[49] This criticism went beyond questions of architectural taste; it was a stinging reference to the political splintering of opinion within the Irish patriotic movement that Norcott believed had been made symbolically manifest in architectural incoherence.

In 1786 Gandon was approached to furnish further plans for a new front for the Commons to the west.[50] At first unwilling, he was pressed into work by the Speaker of the Commons, John Foster and produced two plans in the Ionic Order without pediment.[51] Foster indicated that he was unsatisfied with the plans and, in an act echoing the replacement of Burgh with Pearce, he consulted the Irish MP and amateur architect, Samuel Hayes, who produced new plans. The extension was executed under the supervision of Robert Parke and involved the construction of an Ionic tetrastyle portico with pediment and arched doorways. In order to connect the new façade to Pearce’s south colonnade, rather than replicating Gandon’s screen wall and thus maintaining the symmetry of the principal front, Parke constructed a curved balustraded open colonnade, twelve feet wide (Fig. 5). This was one of the most criticised of the additions to Pearce’s building: William Norcott declared it to be ‘strongest proof of the inconsistence that arises where a multitude is to decide on a subject only fit for the operation of a single mind’.[52] It was during the construction of Parke’s colonnade that a defect in the new heating system caused the House of Commons to catch fire, destroying Pearce’s octagonal chamber.[53] Its replacement, designed by Vincent Waldré in 1792, retained the cockpit theatre layout of Pearce’s chamber but was now entirely circular and externally topped with a much lower dome which could not be seen above the southern parapet. Externally, the south front of the building was now an architectural hotchpotch, lacking symmetry and coherence (Fig. 5). Standing in this state, it swiftly became a powerful symbol representative of the collapse in the authority and prestige of the Irish Parliament.

The political collapse of the Irish Parliament became absolute when volatile infighting in the Patriot Party boiled over into a violent rebellion in 1798. George III urged William Pitt to use the Rebellion to ‘frighten supporters of the Castle into a Union’.[54] Presenting the Irish Parliament as ineffective, factious and lacking efficacy in the face of such a rebellious force, the Castle persuaded many members of Parliament through the use of powerful rhetoric and valuable bribery that union was the only means of securing stability and prosperity in Ireland. The final meeting of the Irish Parliament took place in the Parliament House on 2 August 1800, after which the building was abandoned. The passing of the Act of Union through a combination of political opportunism, scaremongering and bribery brought disparagement and ridicule upon the Irish Parliament and widespread panic about continued prosperity. Popular broadsides declared the members who voted in favour of the Union to be ‘all impudence and froth, who’d sell their country like a piece of cloth’.[55] They were derided ‘as men fond of pleasure’ who would soon be “disburden’d of commerce” whilst the streets of Dublin were ‘grown over with grass’.[56] The Parliament House, by contrast, remained a potent symbol of what the patriots had set out to achieve, though compromised by later architectural additions. These were perceived as symbolic manifestations of the Parliament’s demise and thus the restoration of the Parliament House under new use was seen as a critical symbolic act of assurance demonstrating that the prosperity gained by the Parliament would not be lost under the Union.

In the immediate aftermath of the Union, the Irish Chief Secretary, Charles Abbot, Lord Colchester, viewed the Parliament House as a potential nexus for future patriotic agitation. In order to neutralise the perceived threat, he initially suggested that the building should be demolished and to this end, he ‘caused a valuation to be made by a Person of Eminence in his profession in the City…of the site and materials’.[57] Yet it was clear that such a move would have been met with significant public opposition: ‘what’s to become of our fine Senate House?’ asked one Broadside, whilst William Norcott lamented ‘proud colonnade! and scarce in Europe match’d, how are thy ruins to be maimed and patch’d?’.[58] James Malton had imagined Pearce’s colonnade in ruins populated by impoverished peasants as early as 1792 (Fig. 6). This symbolic link between the material ruination of the Parliament House and the perceived threat to Irish prosperity from the Union was potentially explosive and could only be avoided by finding some use for the building which would both neutralise its political potential and provide reassurance to the Irish populace that the prosperity secured by the Parliament would continue. It will be argued that no more apt institution could have been found to occupy the building than the Bank of Ireland.

‘The Dams and the Weirs must all be your own’: The Bank of Ireland as Parallel of the Parliamentary Irish Patriotic Project 1720-1801

Scant consideration has been given to the role of the Bank of Ireland in the development of the Irish patriotic project. An examination of its establishment, function and, more crucially, its architectural self-fashioning reveals a symbiotic relationship between Bank and Parliament which made the Bank not only the Parliament’s parallel partner in the promotion of the Irish patriotic project but also its natural successor as occupant of the Parliament House. Daniel Abramson has strongly argued that the architecture of the Bank of England, as a quasi-state body, was firmly part of English ‘state building as a cultural and symbolic act’.[59] No such analysis has been applied to the Bank of Ireland which, in its architecture and iconography, provides an example just as rich.

The parallel role of the Bank in the Irish patriotic project has, perhaps, been obscured by misconceptions surrounding the Irish Parliament’s initial and seemingly illogical distaste for the Bank scheme. In 1719, a group led by the Earl of Abercorn placed a petition before the King pointing to the ‘general decay of trade’ in Ireland and recommending that a National Bank be established there.[60] Initially, the Commons were enthused, declaring on 28 September 1721 that ‘the establishing of a Public Bank under proper Regulations and Restrictions will greatly contribute to the restoring of credit and the support of trade and manufactures of this Kingdom’.[61] However, by 9 December, the Commons declared themselves unable to find ‘any safe foundation for establishing a Public Bank’, fearing that it would lead to the ‘most dangerous and fatal consequence[s] to…the Trade and Liberties of this nation’.[62] This extraordinary volte-face is not at all surprising in the wake of the catastrophic collapse of the South Sea Company – a venture which had itself adopted some of the functions of a national bank in England – in late 1721. As William Nicholson, Bishop of Derry sagely commented ‘all the several projects for an Irish Bank were framed about the beginning of June 1720 when the South Sea was in its most flourishing state’.[63] The full disastrous repercussions of the South Sea Bubble and the extent of the political corruption which had underpinned the scheme had become clear across the British Isles by December and there can have been little appetite anywhere for the foundation of another speculative financial institution.[64] But in Ireland, there were, in addition, other more patriotically potent reasons to oppose the bank project. Jonathan Swift had commenced a concerted campaign of satirical pamphleteering against the Bank almost as soon as the project was launched.[65] The primary reason for Swift’s seemingly illogical opposition is revealed in his satiric poem,The Bank Thrown Down, where he declared,

Some mischief is brewing, project smells rank,

To shut out the River by raising the BANK.

The dams and the weirs must all be your own;

You get all the fish and others get none.[66]

For Swift and the Irish Parliament, the Bank scheme was an opportunistic platform for patriotic opposition to English mercantile interests which they suspected were at the heart of this bank project. As a result, the Bank project was subject to a great deal of Parliamentary opposition, cacophonous political debate and public outcry throughout 1721 until the project was abruptly dropped.[67] However, a national bank was not, as a concept, contrary to the aims of the patriotic project. Indeed, with the huge increase in Irish commercial activity and resultant need for public credit precipitated by the granting of Irish free trade in 1779, the need for a bank as a key component of the patriotic project became obvious.[68] A Bill to establish a bank was introduced on 22 April 1782 and passed in both Houses with great speed and without major protest, the first meeting of the Court of Directors taking place on 27 January 1783.[69] Under the terms of its Charter, each member of the Court of Directors was required to subscribe to the declaration contained in the 1704 Act to Prevent the Further Growth of Popery.[70] As a result, its initial Court of Directors was composed entirely of wealthy Protestants of the mercantile class: precisely the class which dominated the Irish House of Commons.[71] For its motto, the Bank chose Bona Fides Reipublicæ Stabilitas (good faith is the cornerstone of the state) further casting itself as parallel actor to the Parliament in stable good government and Irish prosperity.

In establishing its visual identity, the Bank was just as keen to promote its place within the Irish patriotic project. For its seal, it adopted an image of Hibernia independently enthroned with attributes of peace and commerce. Samuel Sproule was appointed first Bank architect in 1782. Edward McParland has ascribed plans for a bank headquarters from this date to him. The external elevation is clearly derived from George Sampson’s designs for the Threadneedle Street façade of the Bank of England (1732-1734). In elevation, the two plans are virtually identical, comprising a building, seven bays wide of two storeys over rusticated basement, centred on a three-bay projection with applied Ionic columns and topped with classical vases on the roofline. These studied similarities are a clear attempt by the Bank of Ireland to fashion itself as equal in legitimacy to the Bank of England, an institution which had by that date ‘emerged as a national institution to be valued and defended’.[72] Furthermore, in adopting what Sir John Soane later deemed to be Sampson’s ‘grand style of Palladian simplicity’ and thus inviting direct comparison with Pearce’s Parliament House, the Bank sent a powerful message about its fraternal role in the Irish patriotic project.[73] In the end, Sproule’s plans came to nothing and in March 1783, the Directors leased a house on Mary’s Abbey.

The Transactions reveal that the Directors were never happy with the Mary’s Abbey site and, throughout the 1780s, they endeavoured to find one that better portrayed the Bank as secure and prosperous. By this time there had been a dramatic shift eastward in the centre of gravity of the mercantile city following the relocation of the Customs House a mile and a quarter downstream and the building of James Gandon’s Carlisle Bridge (1791-1795). The new north-south axis this bridge created along Sackville and Westmoreland Streets became the main focus of commercial activity in the city. Thus, on 19 June 1799, the Court of Directors declared that ‘a piece of ground in the vicinity of the Parliament House [would be] a…fit and convenient one on which to build a bank’ and directed that an application be made to the Lord Lieutenant for approbation of a plan to build on a site recently acquired from Trinity College by the Wide Streets Commissioners for development.[74]

Thomas Williams, Secretary to the Bank, was dispatched to London, and on 27 September 1799 he met Sir John Soane at the Bank of England to discuss plans for Dublin.[75] Williams’ interest in the Bank of England is hardly surprising and commissioning the architect of the English Bank would have seemed a natural choice, particularly as Soane was already working on plans for the Marquess of Abercorn at Baronscourt in County Tyrone. Soane’s daybooks show his office spent extended periods preparing plans for the Irish National Bank from October 1799. Joseph Gandy’s sketchbook demonstrates that many architectural ideas proved equally appropriate for use in both Banks, revealing that both national banks wished to communicate many shared iconographic messages, particularly those of security, authority and legitimacy.[76] In particular, Gandy’s reduced adaption of the fourth-century Arch of Constantine that would eventually be built at the Bank of England in Lothbury Court (1800-1801) seems to have started life as the monumental entrance to the Bank of Ireland. On 18 November 1799, Soane dispatched final drawings to the Bank’s English agent John Puget.[77] Soane’s plans for the Bank of Ireland have been subject to a great deal of aesthetic criticism.[78] Whilst they may lack the austere monumentality of the Bank of England, what has been overlooked in the existing literature is that they are significantly richer in iconographic meaning, for in addition to the shared iconography of security and authority, the Irish Bank also wished to send a strong political message about its place in the Irish patriotic project. At the apex of both domes, a sculpture of Hibernia sits enthroned, crowned by a winged Fame.[79] Britannia, the only other clearly recognisable allegorical sculpture, is relegated to the apex of the west portico on both plans in a distinctly marginalised position. A royal equestrian statue sits atop the triumphal arches at the centre of the elevations but well below Hibernia. The iconographic message was clear: here was an institution which was not only wealthy enough to create a magnificent architectural set piece, but one which fitted perfectly into the symbolic civic space around College Green, a space which had been invested with critical political significance for the Irish patriotic project. Given its history and outlook, the Bank of Ireland clearly wished to promote itself as a torch-bearer for good government, continuity, stability and Irish commerce and self-determination. Unfortunately for Soane, there was a building just across Westmoreland Street that had already been infused with these ideals, a building that had just become vacant with the Act of Union.

‘A Nobler Phoenix from the Ashes Springs’: The Re-fashioning of the Parliament House as Bank of Ireland 1801-1810

The first mention of the potential purchase of the Parliament House by the Bank of Ireland can be found in the Transactions of 1 September 1801 when ‘a ground plan of the Parliament House’ was ‘received by the Governor from Mr Secretary Abbott [sic.]’.[80] Sir John Soane’s Day Books show that the Bank had continued to order plans for the College Street site as late as March 1800, but it had become increasingly impatient with the progress of the scheme.[81] As a result, it appears that the Bank entered into negotiations with Abbot to purchase the Parliament House: these were completed by Deed of Conveyance in August 1803. In negotiating with the Bank of Ireland, Abbot remained primarily concerned that the political symbolism of the building would be neutralised. In a dispatch to the British Home Secretary, Lord Pelham suggests that the Bank initially assured Abbot that it would ‘subdivide what was the former House of Commons…and would apply what was the House of Lords to some other use which would leave nothing of its former appearance’.[82]Abbot wrote to the Lord Lieutenant on 1 February 1802 that ‘it should…be…privately stipulated that the two chambers of Parliament shall be effectively converted to such uses as shall preclude their being used upon any contingency as public debating rooms’.[83] Indeed, when recording the sale in his diary, Abbot declared that he had privately agreed with the Bank ‘that the two chambers of Parliament should be accommodated to the uses of the Bank in some such manner as should completely alter their former size and appearance’.[84] Nothing of this private agreement appears in the Bank of Ireland archive, though the Transactions record that the offer to purchase was entirely ‘verbal’.[85] A meeting of all Proprietors of Bank stock was held on 8 April 1802 ‘to take into consideration the propriety of purchasing the late Parliament House for the purposes of converting the same into a National Bank’.[86] The proposal was passed, and an offer was made to Dublin Castle to purchase the Parliament House for £40,000.[87] The only provision in the written memorandum was a covenant to submit the plans for any alterations to the Lord Lieutenant for approval.[88] This agreement to submit any plans for alteration to the Lord Lieutenant is also reflected in the Deed of Conveyance to the Bank.[89] There is no mention of Abbot’s alleged private agreement in either document, and if ever it was made verbally, it was substantially ignored.

There seems to have been little adverse public comment on the sale, which was cast as a restoration of the reputation of the building after the degradation of the Parliament. As one contemporary wit quipped,

Since to a Bank, as ‘tis asserted,

Our House of Commons is converted;

What most we want will be there,

in place of what we best can spare.[90]

This is perhaps not surprising. After the Union, Ireland retained an independent Exchequer as a last vestige of political independence, and the Bank continued to act as government financier. Symbolically, the Bank thus embodied the perfect balance of interests, representing the fiscal independence and prosperity Parliament had failed to secure but also, as an institution, opposing any political agitation which could harm Irish commerce.

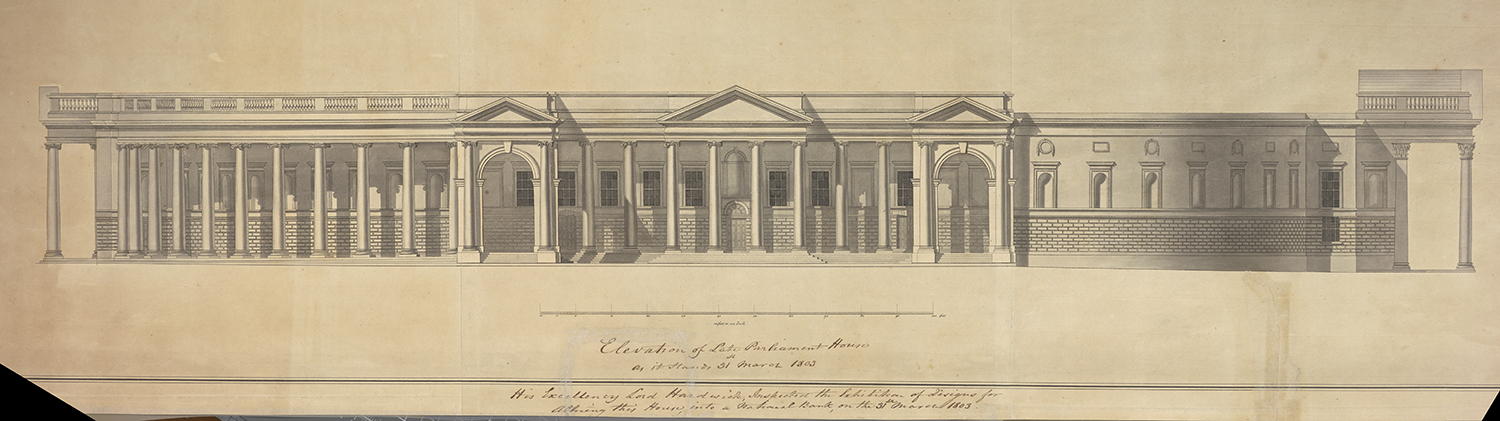

The Bank took possession of the Parliament House on 24 August 1802 and on the same day advertised an architectural competition offering several premiums for plans to convert the Parliament House to a National Bank.[91] The state of the south front prior to works can be judged from an elevation prepared by Francis Johnston in 1803 (Fig. 5). The principal architectural concern was to ‘render the outside uniform, and in the change of appropriation, reconcile the citizens to it’.[92] Approximately forty plans were submitted to the Committee of which about a dozen survive.[93] From those which do survive, it appears that the approach to the existing building varied widely between architects. Two surviving plans advocated the complete demolition of Pearce’s south colonnade, whilst Richard Lucius Louch preserved Pearce’s work entirely unaltered. Public opinion tended towards favouring the latter approach, William Tighe writing that ‘all the artists of taste preserve [Pearce’s] justly admired front to College Green’.[94]

It seems clear from the results of the competition that the Bank agreed that Pearce’s front, with all its symbolic, historic and iconographic meaning, should be preserved intact as a manifesto of continuity. When the Building Committee first reported to the Court of Directors, however, it was to inform them that they had found ‘such difficulty in deciding upon the merits under all the various considerations’ that they were unable to adjudge the competition and would instead ‘express themselves by distinct observations on the subject generally’.[95] They were agreed that ‘no alteration of the external building is necessary for the purposes of the Bank’, but concluded that ‘no one set of designs (as produced) could be implicitly adopted’.[96] With this in mind, the Directors approached Francis Johnston on 30 May 1803 to prepare plans which would assimilate various elements extracted from ten of the entries which had been deemed by the Committee to be commendable.[97] What is most telling about this result is the fact that although two thirds of the entries were by English architects, four of the ten winners were Irish, clearly demonstrating that the patriotic project had not been lost on the Bank. Furthermore, the two surviving entries which did not receive a premium are instructive in that they demonstrate what the Bank did not want: both of them completely obliterated Pearce’s work.[98]

It seems impossible that Francis Johnston was not aware of this and his designs show a high degree of deference to those of Pearce. The Building Committee accepted his plans on 5 July 1803 and the foundation stone for the new works was laid on 8 March 1804.[99] As built, Johnston’s external plan preserves Pearce’s façade entirely unaltered, save for the filling in of the fenestration. Rather than adopting either Parke’s open colonnade or Gandon’s austere astylar screen wall to connect the east and west façades, Johnston assimilated the two by building screen walls with three-quarter engaged Ionic columns. To Pearce’s central portico he added three allegorical statues representing Hibernia enthroned at the apex and attended by Fidelity and Commerce, both critical ideals of the patriotic project.[100] Echoing the patriotic rhetoric of Pearce, Johnston urged the directors that ‘if this work can be accomplished by natives, I am sure… you would give them a preference’ and the commission was awarded to the Irish sculptor Edward Smyth.[101] The exterior is thus marked with the spirit of compromise and continuity as symbolic bringers of Irish prosperity.

This spirit of continuity through compromise is continued in Johnston’s internal works. The most major alterations were the division of Waldré’s Commons chamber into offices and the construction of a new cash office occupying the south wall on the site of Pearce’s Court of Requests. The destruction of the Commons chamber has been raised as evidence that the purchase of the building by the Bank was an aberrational break with Parliamentary continuity. However, Waldré’s chamber was symbolically associated not with the thriving early eighteenth-century patriotic Parliament but rather with its unravelling after 1790, so its destruction surely cannot have been as potently symbolic to the contemporary viewer as many later writers have argued. Indeed, Johnston’s new cash office was significantly more aligned to the work of Pearce than Waldré’s Commons chamber (Fig. 7). In the bold simplicity of its restrained plasterwork and its monumental columns raised on high plinths around the walls, the Cash Office bears a close resemblance to Pearce’s 1728 design for the Court of Requests,[102] which it replaced. Johnston’s deference to Pearce is equally clear in his West Hall, where the heavy three-quarter-height rustication, relieved only by elegant swags between lion’s heads in the entablature, and the compartmentalised coffered ceiling is entirely evocative of Pearce’s work. These spaces may have been new, but their message was one of continuity.

Pearce’s Lords chamber was preserved entirely unaltered. Indeed, Johnston went to some significant lengths to restore its patriotic message by seeking out the tapestries which had been removed from the room ‘with the intention of taking them to England’ in 1801.[103] Stored in a depository of decayed furniture at Dublin Castle, the tapestries were ‘fortunately seen by Mr Johnston… and were, by the good taste of that gentleman, restored to their original and appropriate places’.[104] Their restoration was more than a question of taste: it was a symbolic act demonstrating the place of the Bank as legitimate successor to the Parliament, and as protector of the commercial liberties gained at the Glorious Revolution.

In converting the Parliament House to their new headquarters, the Bank had set forth a powerful manifesto of continuity. Outwardly, the iconographic meanings ascribed to the building in previous decades were restored and emphasised by re-establishing the symmetry of Pearce’s colonnade. The bank chose an Irish architect, employed Irish craftsmen and displayed an acute sensitivity to the work of Pearce, recreating his style where his original interiors had been lost. The Bank thus cast itself as natural successor to the Parliament in the Irish patriotic project. Far from being an aberration, the conversion of the Parliament House to the Bank of Ireland was a natural, logical and iconographically coherent one.

Conclusion

In the tympanum above the tetrastyle portico of James Gandon’s Customs House, completed in 1791, can be found, in alto relievo, ‘the friendly union of Britannia and Hibernia, with the good consequences resulting to Ireland’ carved by Edward Smyth.[105] Britannia is shown confidently holding the cap of liberty and an olive branch, Hibernia entreating her for assistance by her side, whilst Neptune expels famine at her beckoning. Here, eloquently, but insistently, is made manifest the English post-Union vision of a prosperous, but subordinate, Ireland bound to Britain by barter.[106] By contrast, when Smyth was commissioned to carve a figure for the apex of Pearce’s Parliament House portico, he fashioned an imperious and determined Hibernia, enthroned alone upon a roughly-hewn rock (Fig. 8). Her defiant gaze meets the viewer directly, her left arm resting on the Irish harp and her right resolutely thrust out to display an olive branch.[107] This defiantly independent Hibernia was commissioned not by the politicians who once inhabited the building, but by the Bank of Ireland. The Parliament House was saturated with iconographic and symbolic references to the fundamental tenets of Irish patriotism. As the Irish patriotic project began to unravel after 1779, so too did the unity of the architecture of the Parliament House. Architectural interventions, though instigated with the intention of improvement, were perceived as potently symbolic of the debasement of the Parliamentary institution in the years immediately preceding the Union. There was a popular movement to restore the building to its former magnificence as a symbolic act of reassurance to the Irish Protestant patriotic class.[108] No more suitable occupant could be found to restore the reputation of the building and adopt its continued iconographic message than the Bank of Ireland. To proponents of the patriotic project, betrayed by Parliament at the Union, the Bank had established itself – both in its function and visual identity – as a pivotal actor in the promotion of Irish patriotic principles. The adoption of the building by the Bank was an act of iconographic continuity which kept the Irish patriotic project alive for several decades after the Union until it was obscured in the cultural and political mêlée of the later nineteenth century, when this brand of outward-looking, commercially centred Protestant patriotism was eclipsed by the inward-looking patriotism of the Celtic revival, based on shared culture, language and Roman Catholic faith.

Citations

[1] See, for instance, Maurice Craig, ‘The Quest for Sir Edward Lovett Pearce’, Irish Arts Review Yearbook, 12 (1996), 96-106, 96.

[2] ‘The First Home of Home Rule’, Pall Mall Gazette, 15 February 1886, 11. Maurice Craig, Dublin 1660-1860 (London: Cresset Press, 1952).

[3] Section 66(1) Government of Ireland Act (10 & 11 Geo 5 c. 67), 1920.

[4] See, for instance, Clyve Jones and Sean Kelsey (eds.), Housing Parliament: Dublin, Edinburgh and Westminster (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2002) and Robin Usher, Protestant Dublin 1660-1760: Architecture and Iconography (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012).

[5] Sean Kelsey, ‘Housing Parliament: Dublin, Edinburgh and Westminster’, Parliamentary History, 21, 1 (February 2002), 1-21, 1.

[6] Edward McParland, ‘The Bank and the Visual Arts’, in F.S.L. Lyons (ed.), Bicentenary Essays: The Bank of Ireland 1783-1983 (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan, 1983), 96-139, 97.

[7] Usher, 2.

[8] A.P.W. Malcomson, Nathaniel Clements, Government and the Governing Elite in Ireland, 1725-1775 (Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2005).

[9] David Hayton, Ruling Ireland 1685-1742 (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2004), 39.

[10] Henry Grattan, Speech in the Irish House of Commons, 16 April 1782, in Daniel Owen Madden (ed.), The Speeches of the Rt. Hon. Henry Grattan (Dublin: James Duffy, 1871), 74.

[11] Hayton, 38.

[12] Journals of the House of Commons of the Kingdom of Ireland (Dublin: George Grierson, 1796), vol. III, Appendix, 10 January 1727 (old style), ccclviii. See John T. Gilbert, An Account of the Parliament House Dublin, 1661-1800 (Dublin: Hodges Figgis & Co., 1896), 22. See also Edward Watson, ‘The Irish Parliament House. Who was the Architect?’, The Irish Builder and Engineer, 8 June 1929, 515-524, 516. Journals of the House of Commons of the Kingdom of Ireland hereafter abbreviated as JHCI.

[13] Edward McParland, ‘Building the New Parliament House, Dublin’, Parliamentary History, 21, 1 (February 2002), 131-140, 137.

[14] An Act for Securing the Dependency of the Kingdom of Ireland Upon the Crown of Great Britain (6 Geo. 1 c. 5), 1719. See T.B. Howell (ed.), Cobbett’s Complete Collection of State Trials (London: T.C. Hansard, 1812), vol. XV, 1302-23; Francis Plowden, An Historical Review of the State of Ireland (London: T. Egerton, 1803), 249.

[15] Watson, 518.

[16] Edward McParland, ‘Edward Lovett Pearce and the New Junta for Architecture in Eighteenth-Century Ireland’, Lecture delivered to the University of Notre Dame, Indiana, October 1991, IAA 2008/44/92; Edward McParland, ‘Edward Lovett Pearce and the New Junta for Architecture’, in Toby Barnard and Jane Clarke (eds.) Lord Burlington: Architecture, Art and Life (London: Hambledon, 1995), 151-166; Edward McParland, ‘Sir Thomas Hewett and the New Junta for Architecture’, in The Role of the Amateur Architect: Papers given at the Georgian Group Symposium 1993 (London: Georgian Group, 1994), 21.

[17] JHCI (Dublin: George Grierson, 1796), vol. III, 564.

[18] See Edward McParland, Public Architecture in Ireland 1680-1760 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2001), 188.

[19] Richard Proby, ‘The Allens of Stillorgan’, in Howard Colvin and Maurice Craig (eds.), Architectural Drawings in the Library of Elton Hall by Sir John Vanbrugh and Sir Edward Lovett Pearce (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1964), xiii-xxxi.

[20] See The Knight of Glin, ‘New Light on Castletown’, Quarterly Bulletin of the Irish Georgian Society, 3, 1 (January-March 1965), 3-9, and Maurice Craig and the Knight of Glin, ‘Castletown, Co. Kildare’, Country Life, 145 (27 March 1969), 722-766. JHCI (Dublin: George Grierson, 1796), vol. III, 550.

[21] McParland (2001), 188-191.

[22] McParland (2001), 191

[23] Sir Edward Lovett Pearce, An Explanation of the Following Designs for a Parliam.t House in Dublin 1728, NLI MS 20, 209.

[24] Sean Kelsey, ‘Housing Parliament: Dublin, Edinburgh and Westminster’, Parliamentary History, 21, 1 (February 2002), 1-21, 10.

[25] James Stevens Curl, Georgian Architecture (London: David & Charles, 1993), 23; Tim Richardson, The Arcadian Friends: Inventing the English Landscape Garden (London: Bentham Press, 2008), 95-98.

[26] Inscribed in Latin on the pediment as ‘Ob Religonem Conservatom, Restitutas legas, Libertatem Assertam’.

[27] Sean Murphy, ‘The Dublin Anti-Union Riot of 3 December 1759’, in Gerard O’Brien (ed.), Parliament, Politics and People (Blackrock: Irish Academic Press, 1989), 52-56.

[28] Henry Fox, Lord Holland, Memoirs of the Reign of King George the Second by Horace Walpole, 3 (London: Henry Colburn, 1846) 241-242;

[29] Usher, 110.

[30] Toby Bernard, ‘The Viceregal Court in Later Seventeenth-Century Ireland’, in Eveline Cruickshanks (ed.), The Stuart Courts (Stroud: Sutton, 2000), 256-265, 261.

[31] Henry Brooke, A Fragment of the History of Patrick (London, 1753), 8.

[32] Sir Edward Lovett Pearce, A proposed Plan and Elevation of the New Parliament House, 1728, pen and wash drawing, The Proby Collection, The Victoria and Albert Museum, Vanburgh Album E.2124:165-1992, London. Image available on the V&A website.

[33] NLI MS 20, 209.

[34] NLI MS 20, 209.

[35] See Edward McParland, ‘Edward Lovett Pearce and the Parliament House in Dublin’, The Burlington Magazine, 131, 1031 (February 1989), 91-100, 93.

[36] Bank of Ireland Public Relations Department, The Bank of Ireland, College Green (Pamphlet, Dublin, 1978).

[37] Letter of Robert Howard, Bishop of Elphin, to Hugh Howard, 2 November 1731 quoted in McParland (2001) 187.

[38] Ada K. Longfield, ‘A History of Tapestry Making in Ireland in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries’, Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, 68 (1938), 91-105.

[39] Journals of the House of Lords of the Kingdom of Ireland (Dublin: William Sleater, 1779), vol. III, 6 February 1727, 35.

[40] See Phillis Rogers, ‘The Armada Tapestries in the House of Lords’, RSA Journal, 136.5386 (September 1988), 731-735. Journals of the House of Lords of the Kingdom of Ireland (Dublin: William Sleater, 1779), vol. III, 17 February 1727, 41.

[41] See Journals of the House of Lords of the Kingdom of Ireland (Dublin: William Sleater, 1779), vol. III, 17 February 1727, 41; Longfield, 95-96.

[42] Repeal of Act for Securing Dependence of Ireland Act, 1782 (22 Geo. III, c. 53).

[43] Daniel Owen Madden (ed.), The Speeches of Henry Grattan (Dublin: James Duffy & Sons, 1853), 70.

[44] Usher, 164-165.

[45] James Gandon (Jnr) and Thomas J. Mulvaney, The Life of James Gandon Esq. (Dublin: Hodges & Smith, 1846), 50.

[46] Office of Sir John Soane, Proposed design for the Bank of Ireland on the College Street – Westmoreland Street Site, 1800, ink and watercolour, Sir John Soane’s Museum, London. Image is available online at http://collections.soane.org/THES75437 [Last accessed: 29 October 2018]

[47] Gilbert, 90.

[48] See, for instance, William John Lawson, The History of Banking (London: Richard Bentley, 1855), 378.

[49] William Norcott, The Metropolis (Dublin: J. Barlow, 1805), 18.

[50] Gandon and Mulvaney, 112.

[51] Gandon and Mulvaney, 112 and 114-116.

[52] Norcott, 18-19.

[53] C. P. Curran, ‘The Parliament House 1728-1800’, in F. G. Hall, The Bank of Ireland 1783-1946 (Dublin: Hodges Figgis, 1949), 425-454, 449.

[54] NLI MS 886, f.323, Letter from King George III to William Pitt, 13 June 1798.

[55] William Norcott (attrib.), The Law Scrutiny; or the Attornies’ Guide (Dublin: J Barlow, 1807), xiii.

[56] Oireachtas Library, GH/0000007(1), Anon, The Union: A Lyric Canto Appointed to be Sung, or Said, in All Meeting Houses (Broadside, undated, Dublin, ca. 1800).

[57] ‘Dispatch Concerning Parlt. House, Dublin, Decr. 12th 1801 [from Lord Hardwicke to] Lord Pelham’, quoted in Edward McParland, James Gandon: Vitruvius Hibernicus (London: A. Zwemmer Ltd., 1985), 200.

[58] Oireachtas Library, GH000007(1), The Union: A Lyric Canto (Dublin, undated, ca.1800); Norcott, 18.

[59] Daniel M. Abramson, Building the Bank of England: Money, Architecture, Society 1694-1942 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2005), 240.

[60] See F.G. Hall and C.P. Curran, The Bank of Ireland 1783-1946 (Dublin: Hodges Figgis, 1949), 16-21.

[61] JHCI (Dublin: Abraham Bradley, 1782), vols IV and V, 28 September 1721, 470.

[62] JHCI (Dublin: Abraham Bradley, 1782), vols IV and V, 9 December 1721, 537; JHCI (Dublin: George Grierson, 1796), vol. III, 12 December 1721, 289-290.

[63] Oxford ChCh, Wake XII.289, letter of William Nicholson, Bishop of Derry, to William Wake, Archbishop of Canterbury, 21 October 1721.

[64] Oxford ChCh, Wake XIV.1, Letter of Edward Synge, Bishop of Elphin, to William Conolly, 1722.

[65] Sean Moore, ‘Satiric Norms, Swift’s Financial Satires and the Bank of Ireland Controversy of 1720-1721’, Eighteenth Century Ireland / Iris an dá Chultúr, 17 (2002), 26-56.

[66] Lawson, 353; Jonathan Swift, The Bank Thrown Down. To an Excellent New Tune (Broadsheet, John Harding, Dublin, 1721).

[67] ChCh Oxford, Wake XIII.288-307.

[68] JHCI (Dublin: Abraham Bradley, 1782), vol. XIX, 24 February 1780, 268; JHCI (Dublin: George Grierson, 1796), vol. IX, 24 February 1780, 77 and 25 February 1780, 78.

[69] JHCI (Dublin: George Grierson, 1796), vol. X, 22 April 1782, 336 (first reading); 23 April 1782, 339 (second reading and committed); 25 April 1782, 344 (in committee); 26 April, (third reading, passed and sent to Lords); 4 May 1782, 349 (passed by Lords without amendment); 4 May 1782, 350 (Royal Assent). Journals of the House of Lords of the Kingdom of Ireland (Dublin: William Sleater, 1784), vol. V, 4 May 1782, 323. Bank of Ireland Archive, Dublin, BOI-V-H-000347-2796948 Court of Directors Transactions, Book no. 1, 3.

[70] Act to Prevent the Further Growth of Popery (2 Ann c.6).

[71] See Whitaker, ‘Origins and Consolidation 1783-1826’ in Lyons, 10-29, 27.

[72] Abramson, 120.

[73] Bank of England Archive, M5/262-267, Committee of Building Minutes.

[74] Court of Directors Transactions, Book no. 3, 234.

[75] Sir John Soane’s Museum, Office Day Book of Sir John Soane, 27 September 1799.

[76] Sir John Soane’s Museum, SM69, Sketchbook of Joseph Gandy.

[77] Image is available online at http://collections.soane.org/THES75437 [Last accessed: 29 October 2018]

[78] Edward McParland, ‘The Bank and the Visual Arts’, in Lyons, 96-139, 101. See also Brenda Doyle, Catalogue of Architectural Drawings Entered for the Competition held in 1802-3 for the Alteration of the Old Parliament House, Dublin to the Bank of Ireland (Thesis submitted to Trinity College Dublin for the Moderatorship Part II Examination, April 1986), 18-19 and C. P. Curran, ‘The Building of the Bank 1800-1946’, in Hall and Curran, 455-471, 456.

[79] Image is available online at http://collections.soane.org/THES75437 [Last accessed: 29 October 2018]

[80] Court of Directors Transactions, Book no. 4 (Bank of Ireland Archive, BOI-V-H-000347-2774866), 34.

[81] London, Sir John Soane’s Museum, Sir John Soane’s Day Books, 5 March 1800 where Thomas Sword is recorded as having worked on a perspective drawing for the Bank.

[82] ‘Draft of a Dispatch to Lord Pelham’, quoted in W. E. H. Lecky, A History of Ireland in the Eighteenth Century (London, Bombay and Calcutta: Longmans, Green & Co., 1913), vol. 5, 418.

[83] ‘Letter from Abbot to Lord Hardwicke’, 1 February 1802, quoted in Lecky, vol. 5, 418.

[84] Charles Abbot, Lord Colchester (ed.), The Diary and Correspondence of Charles Abbot, Lord Colchester (London: John Murray, 1861), vol. 1, 285.

[85] Court of Directors Transactions, Book no. 4, 73.

[86] Court of Directors Transactions, Book no. 4, 70.

[87] Court of Directors Transactions, Book no. 4, 73.

[88] Court of Directors Transactions, Book no. 4, 73.

[89] Bank of Ireland Archive, College Green Vaults, 7 August 1803.

[90] IAA 9/33 P.17, photograph of anonymous manuscript, 1801.

[91] Court of Directors Transactions, Book no. 4, 106; Saunders’s Newsletter, Friday 27 August 1802.

[92] Letter from Abbot to Lord Hardwicke, 1 February 1802, quoted in Lecky, vol. 5, 418.

[93] Freeman’s Journal, 2 April 1803; Faulkner’s Dublin Journal, 28 June 1803.

[94] Diary of William Tighe, 13 April 1803, quoted in Curran, 458. See also James Brewer, The Beauties of Ireland (London: Sherwood, Jones & Co., 1825), vol. 1, 77.

[95] Court of Directors Transactions, Book no. 4, 160-161.

[96] Andrew Caldwell, Sackville Hamilton and Frederick Trench, Observations on Appropriating the Parliament House to the Bank of Ireland by Different Hands (Dublin: James Draper, 1803), 1 and 10.

[97] Court of Directors Transactions, Book no. 4, 154.

[98] The remaining entries were presumably returned to the architects.

[99] Court of Directors Transactions, Book no. 4, 163.

[100] Viola B. M. Burrow, ‘Edward Smyth’, Dublin Historical Record, 52, 1 (Spring 1999), 62-74, 72.

[101] Letter from Francis Johnston to the Court of Directors of the Bank, 5 January 1807, quoted in Curran, 463.

[102] Sir Edward Lovett Pearce, Design for the Court of Requests at the Parliament House, Dublin, 1728, pen and wash, The Proby Collection, The Victoria and Albert Museum, Vanburgh Album E.2124:4-1992, London. Image available on the V&A website.

[103] John Warburton, James Whitelaw and Robert Walsh, History of the City of Dublin (London: T. Cadell, 1818) quoted in Curran, 452.

[104] Brewer, vol. 1, 79.

[105] Barrow, 65-70.

[106] Usher, 164-165.

[107] Burrow, 72.

[108] Norcott, n.p.