Patterns of Intention: Royal chapels in the crown of Aragon (fourteenth and fifteenth centuries) and the Capilla de los Reyes in the convent of Saint Dominic, Valencia[1]

The British Library collections include an exceptional manuscript illuminated in Valencia for Alfonso V, King of Aragon, Sicily and Naples.[2] This lavish book of prayers, or psalter and hours, copied and illuminated in Valencia by Leonard Crespí and other artists between 1436 and 1443, was soon sent to Naples, where the king had established his court, although it was probably conceived for use in Valencia. A significant number of the miniatures illustrate royal devotion in various settings, ranging from grand chapels to private oratories or even what appears to be a royal chamber (Fig. 5.1). Despite efforts to identify such settings with the halls, rooms and royal chapel in the Palau del Real in Valencia, inevitably there has been confusion, since this royal residence was demolished during the Peninsular War in 1810.[3] We can, however, consider one well-known and exceptionally well-preserved building, commissioned by the king himself, and (re)consider its possible function(s), or, in Baxandall’s terms, assess the intentions behind its founding. I refer to the exceptional chapel, famous for its tenebrous grey diamond vaults, that was built within the convent of Saint Dominic in Valencia between 1439 and 1463 (Fig. 5.2). According to Francisco Sala’s unpublished history composed in 1608, the capilla de los Reyes (King’s Chapel) was designed to be the burial place of Alfonso V and his wife, Maria of Castile, but there is no earlier evidence for this.[4] Moreover, Sala was drawing on oral sources rather than documents, in the context of the transfer of Alfonso’s body from Naples to the king’s final resting place in the Aragonese royal pantheon in the monastery of Poblet.[5] When Emperor Charles V, heir of the kings of Aragon, donated the ius sepelendi of the Valencian chapel to Mencía de Mendoza and her parents, the Marquises of Zenete, he referred to it as a ‘royal chapel which is founded under the invocation of the three kings’.[6]

It was a royal chapel indeed. Founded by the king in 1437, it belonged to a tradition of places of worship associated with royal residences in different cities in the Crown of Aragon, an entity composed by three kingdoms and a principality that were united only by the rule of a single dynasty. In an age of itinerant kingship, it was imperative to display magnificence, not only through palaces and residences, but also through chapels, cathedrals, monasteries and oratories. These religious spaces functioned as stages of royal piety, underscoring the king’s special relationship with the sacred in a context of rivalry with other Iberian and European monarchies.[7]

From 1277, the court moved from kingdom to kingdom, transporting the royal chapel from one residence to another.[8] But a substantial change took place during the reign of Peter IV (1336–1387), when the king decided to establish chapels endowed with a set of images and liturgical objects in every major royal residence. In addition, ceremonies had to be performed in the same way in every kingdom, according to the Ordinacions de Cort or Court Ordinances, a ceremonial established by Peter IV, closely following the precedent of the Leges Palatinae of the kingdom of Majorca (1337).[9] As a result of these decisions, a cohesive image of monarchic piety took shape through ceremonies and the appearance of high altars, as well as through the number of priests and acolytes celebrating the Divine Office in the royal chapels. These included Zaragoza and Huesca in Aragon, Valencia (Palau del Real), and Barcelona and Lleida in Catalonia, though the Almudaina Palace in Majorca and the Castle of Perpignan were soon added to this list, following the annexation of this independent kingdom.[10] One of the principal ceremonies was the veneration and display of the royal reliquary, sumptuously furnished and exhibited with a silver altarpiece in the chapel, and attended by the king on special occasions.[11]

These architectural settings should be analysed in terms of local traditions, international models from other courts, and occasional innovations—albeit within tight constraints.[12] The chapel was only one part of a castle or palace, built in a long process of consecutive interventions by several members of the dynasty or inherited from former owners, as in the case of the Palace of the Kings of Majorca in Perpignan, dating from the early fourteenth century, or the chapel of Castel Nuovo in Naples, the only part of the Angevin residence to be carefully preserved by Alfonso in the extensive reconstruction of the fortress in the mid-fifteenth century.[13] This local tradition and sense of place were sometimes overwhelming, as in the case of Palermo’s Cappella Palatina, an extraordinary chapel that was lavishly decorated with mosaics and a sophisticated muqarnas ceiling, surely regarded as an intangible legacy of those kings of Aragon who had previously been kings of Sicily, such as James II or Martin I.[14] It has also been suggested that Barcelona Cathedral may have been conceived as a palatine and episcopal church. Although this project was eventually frustrated, it would nevertheless explain some unusual features of this building, such as its western tribune, which offers an uninterrupted view of the crypt of Saint Eulalia.[15]

Given their strong diplomatic and cultural relations, it is almost certain that the kings of Aragon kept an eye on other royal chapels in the neighbouring kingdoms of Castile, Navarre, Portugal and particularly France.[16] Cultural exchange between Paris and the court of Aragon intensified during Peter IV’s reign due to the successive marriages of his son and successor, future King Juan I with two French princesses (Mata of Armagnac and Violant of Bar, niece of Jean de Berry).[17] The French model of the Sainte-Chapelle was not overlooked when the monarchs of Aragon erected a royal chapel based on relic worship in the fourteenth century: we know that in 1398 Martin I asked Charles VI for detailed information about rites and customs in Paris, so that they could be observed in Barcelona.[18] A copy of the service of the relics has been linked to the chapel in Barcelona; dating from circa 1400–10 and of Spanish origin, it is now in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris.[19] The kings of Aragon were following the example of French princes and aristocrats close to the Valois dynasty, who founded royal chapels similar to the Parisian Sainte-Chapelle in a fashion characterised by relic worship and a significant connection to the royal sanctity of Saint Louis.[20] In this way, they distinguished themselves from their counterparts in Castile, where the court chapel was itinerant and oriented towards ordinary cult in the palatium, while royal chapels in cathedrals or monasteries were devoted to funerary rituals and dynastic commemoration. Moreover, in the royal pantheons in cathedrals such as Toledo and Córdoba, interference by bishops and chapters in the sculptural decoration and architectural setting could not be avoided.[21]

Different patterns of intention can be suggested for other initiatives, such as the construction after 1302 of the royal chapel in the palace in Barcelona by architect Bertran Riquer, in accordance with the will of James II (Fig. 5.3). It has been convincingly argued that the choice of a painted wooden ceiling on diaphragm arches in this oratory was linked to the Franciscan spiritual movement and the ideas conveyed by authors such as Arnau de Vilanova (ca. 1240–1311). More specifically, these values were visualised in the ceremony of Mandatum on Maundy Thursday, when the king washed the feet of twelve poor men to commemorate the actions of Jesus Christ and his disciples before the Last Supper.[22] This custom was ritualised by subsequent members of the dynasty but found its most suitable setting in the royal chapel of the palace in Barcelona.

The tradition of having a royal residence within abbeys and convents prompted the creation of oratories or chapels for royal services.[23] Given that Martin I built a royal residence in Poblet, the chapel of Saint Martin in the former Carthusian monastery of Valldecrist (Altura, Castellón) might well be explained by the king’s devotion to relics and his original intention to participate in monastic life there. Pope Benedict XIII granted indulgences to those who attended the display of the relics in Valldecrist (1413).[24] This chapel with a crypt was covered by an innovative Gothic timbrel vault consisting of two layers of intersecting bricks forming a kind of shell. It was built by Pere Balaguer and consecrated in 1401, and it provided an oratory for the king and for Queen Maria de Luna close to their lodging in the monastery; the crypt may have been a burial place serving as an alternative to the royal pantheon in the Cistercian abbey of Poblet (Fig. 5.4).[25]

As these examples show, we should not examine royal chapels from a strictly formal standpoint, and we must certainly not consider their condition stable, even though ceremonies were ritualised and dynastic continuity was reinforced in these places of magnificence and royal piety. Despite the efforts of Peter IV to enforce homogeneous decoration in his kingdom’s royal chapels through the appointment of painters such as Ferrer Bassa and Ramon Destorrents and goldsmiths like Pere Bernés, there were a variety of altarpieces which could be silver-gilt or painted and, on occasion, even included sculpted images. Reliquaries were no less varied in terms of form and material; the only requirement was that their contents be visible. The mobility of the court was a common trend that demanded frequent travelling with the royal chapel, but even if a long stay took place in one palace, the liturgical calendar prompted changes in the staging of its chapel. This staging included the altarpiece and the furnishings that displayed the relics, as described by messengers from Barcelona who visited the palatine chapel of Naples’ Castel Nuovo on the Feast of Saint Eulalia in 1452.[26]

To unpick those patterns of intention that reveal royal ideals and forms of devotion, it is essential to examine closely the Aragonese kings’ various initiatives regarding the spaces and functions of their royal chapels. First and foremost, ceremonies had to be adapted to different spaces: even though it was very common to have two chapels in royal residences (one for the king, one for the queen), it was not necessarily so if the queen had her own palace, as was the case in Barcelona.[27] Some queens even managed to introduce more intimate places of prayer: Maria of Navarre, Eleanor of Sicily and Maria de Luna did precisely this in the royal chapel in Barcelona (Fig. 5.5).[28]

By the mid-fourteenth century, the Ordinacions de Cort had defined a calendar of ceremonies and liturgical endowments, but this text pays no attention to architectural setting. However, a gallery or platform is a common feature in most of the chapels, including that of Santa Ágata (formerly devoted to Saint Mary) in Barcelona and the one built by Peter IV in Lleida Castle.[29] Both were probably linked to relic worship, and to the need to see the high altar and highlight royal presence in the chapel while keeping the monarch separate. We even know that raised platforms or balconies were built onto royal apartments to overlook the church, as was done for Martin I in Poblet. The king requested a similar structure to attend services at the Carthusian monastery of Valldecrist in 1406.[30] The introduction of new forms of devotion was an essential prompt for the construction of such oratories, described by Francesc Eiximenis as ‘a little house where they can pray almost in secret’.[31] Much more private than a royal tribune, these oratories can be connected to such texts as the Quarentena de contemplació by Joan Eximeno or others by authors such as Eiximenis who exerted a great influence at court.[32]

Both kings and queens nonetheless established chapels, oratories and chambers in monasteries and convents in the Crown of Aragon, sometimes as part of a project including a pantheon, church and royal residence. That is certainly the case with Santes Creus and Poblet, the two Cistercian monasteries in Catalonia. It was almost mandatory to entrust worship in a royal chapel to a religious community, since they offered continuity and vigour in Divine Office prayers.[33] Martin I chose the Celestines for the royal chapel in the palace of Barcelona, erected on the precedent of the Sainte-Chapelle, though he had also established oratories in the very same royal palace (the Chapel of Saint Michael) and in Barcelona Cathedral.[34]

The Capilla de Los Reyes (Kings’ Chapel) in the Convent of Saint Dominic, Valencia

Alfonso V (1396–1458), the second king from the House of Trastámara to occupy the throne of Aragon, modified the traditions of his predecessors. Having transferred the royal chapel in the palace of Barcelona to the Mercedarian friars in 1423, he eventually abandoned Martin I’s project in that city and ordered that the reliquary, augmented by Martin I not long before, be moved to Valencia.[35] Several reasons may explain this change in favour of Valencia. First, the city, which had been emerging since the late fourteenth century as one of the capitals of the Crown of Aragon, supported Alfonso’s ambitions to conquer the kingdom of Naples, and defended his family interests in neighbouring Castile by offering financial contributions to both initiatives.[36] Meanwhile, the king himself ordered an extensive programme of work on his residence, the Palau del Real, and was arguably flattered by the city’s efforts to welcome him as a prince in 1414, to celebrate his marriage to Princess Maria of Castile the year after, and, finally, to commemorate his royal entry in 1424.[37] The Aragonese court’s temporary stay in Valencia, improvements to the Palau del Real, and the commissioning of Valencian artists and architects further strengthened the king’s relationship with the city.[38]

Did Alfonso V always intend to transfer the royal chapel (and relics) from Barcelona to the new chapel in the Convent of Saint Dominic in Valencia, as Francesca Español wondered some years ago? Or is it the case, as is more commonly believed, that the relics ended up there because they were offered as security for a loan to Alfonso V from the cathedral’s treasury in 1437?[39] This possibility is further explored below, as it offers meaningful insights into the type, functions and particular features of the chapel in the convent of Saint Dominic (Fig. 5.6).

Built between 1439 and 1463 by architect Francesc Baldomar, the chapel still makes a powerful statement within the convent of Saint Dominic, thanks to its external grey wall with Alfonso’s heraldry on Plaza de Predicadores.[40] Its monumental presence is, however, only completely revealed when the rectangular space (eleven by twenty-two metres inside) is entered, with walls two and a half metres thick, covered with a diamond vault made up of two rectangular bays with a pointed groin vault, with lunettes and another bay that creates the effect of a semi-octagonal apse on the western side, with pointed squinches in the corners (Fig. 5.7).[41] The bricks and mortar used in central European diamond vaults were rarely used in Valencian vaults in this period, but the grey limestone chosen for royal chapel was equally unusual.[42] It was brought directly from the Sagunto quarries, about twenty-five kilometres away, whereas most Valencian Gothic buildings used local white limestone from Godella; the latter was more convenient as it is was both nearer and suitable for stonecutting.[43] The records of work on the chapel mention frequent sharpening of tools, probably due to the hardness of the grey limestone. One reason to employ this hard, dark grey stone could be its prestige, which derived from its use in ancient monuments in the region and its provenance from Saguntum with its Roman ruins and theatre.[44]

The choice of the grey stone, the location of the chapel near the main access to the church of the Predicadores and the presence of two niches at each side of the nave have all been explained as a consequence of its funerary function.[45] Valencian citizens and noble families were enthusiastic patrons of the Dominican convent, making it their preferred burial location, and the monarchy had protected the friars since the Christian conquest in 1238.[46]

Less attention has been paid to other intriguing features, such as the presence of one opening high on the south side, close to the apse at the west end; a chamber covered with an irregular groin vault, thought to be a sacristy behind the semi-octagonal apse; and two intertwined spiral staircases, one reaching a terrace with a small well in the centre (a type known as caracol de Mallorca), the second connected to an opening in the centre of the apse. A pulpit and a narrow staircase have been excavated out of the northern wall. What is certainly beyond any doubt is the royal patronage of the chapel, even if it is not recorded in written sources: the heraldry of the kingdoms of Aragon, Sicily and Naples is proudly exhibited above the main entrance from the convent atrium (Fig. 5.8).

The origins and construction of the chapel can be followed from the accounts in the Archivo del Reino de Valencia.[47] In these and other associated records, there is no mention of the chapel’s funerary use: it is always referred to as the ‘capilla de los Reyes’ or the chapel ordered to be built by King Alfonso. The only reference to the niches is to the retret del senyor rey and retret de la senyora reyna, using a Catalan term roughly equivalent to the French retrait, which refers to small niches in the wall to be occupied by the king and the queen, as the heraldry once again confirms. In 1443 five chaplaincies were each endowed with one thousand sous a year to celebrate Masses for the king.[48] When concealed with curtains, the niches probably looked similar to the famous miniature depicting Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, at prayer inside an oratory while attending Mass.[49]

Comparison with other funerary chapels and royal pantheons in the Crowns of Aragon (Poblet, Santes Creus) and Castile (Miraflores, royal chapels in Sevilla, Córdoba and Toledo) raises questions about the location of the tombs—if they were really intended for the Valencian chapel—and their relationship to the retrets.[50] It is hard to imagine that the royal sepulchres were to be placed in the retrets, leaving almost the whole width of the chapel free: it is more likely that they were intended for the centre of the chapel. Both niches remained empty anyway, since Alfonso was buried in Naples until his corpse was transferred to Poblet in 1671 (by order of the Spanish viceroy of Naples, Peter Antonio de Aragón), while Maria of Castile founded a convent of Poor Clares in Valencia where she chose to be buried in a tomb without an effigy, decorated only with personal heraldry.[51] Not even King Juan II made use of this extraordinary shrine, even though he took on responsibility for finishing the chapel, and commissioned the painter Joan Reixach to make an altarpiece for it. He was instead buried in the royal pantheon at Poblet.

There is little evidence for the function of the chapel before Emperor Charles V passed it on to Mencía de Mendoza as a burial place for her parents, the Marquises of Zenete. Initial intentions for the chapel seem to have been condemned to oblivion, unless we turn to circumstantial insights into the original conception of this structure which has long been admired as a masterpiece of late Gothic stonecutting and innovative vault design.[52]

The first piece of evidence is found in the psalter and hours of King Alfonso, located at the British Library in London.[53] In some of the miniatures, we see the king in intimate prayer inside small shrines or oratories, in a setting similar to the royal chapel in Valencia, then at an early stage of its construction. These miniatures convey an image of monarchic piety not only on a courtly stage—as in the miniature identified with the palatine chapel (fol. 281v) (Fig. 5.9)—but also in more intimate chambers and shrines located in or outside the royal residence (fol. 14v, in the royal chamber; fol. 38r, of interest because of the textile oratory; 44v, in front of a crucifix within a small chapel; fol. 106v, before an oratory in a garden; fol. 263v, inside a mendicant church; fol. 312r, with a vision of the Virgin inside a chapel) (Figs 5.10 and 5.11).[54] It should be noted that this prayer book was originally commissioned by Cardinal Joan de Casanova, a Dominican friar and royal confessor whose influence was probably key in the choice of iconography and decision to make this book ‘for the need and use of the royal person’. The laudatory biography by Antonio Beccadelli, De dictis et factis Alphonsi regis Aragonum, stresses the king’s commitment to the Liturgy of the Hours under all circumstances and his special veneration of the Eucharist, while the prayer book confirms royal devotion to the Seven Joys of Mary and to the Passion.[55]

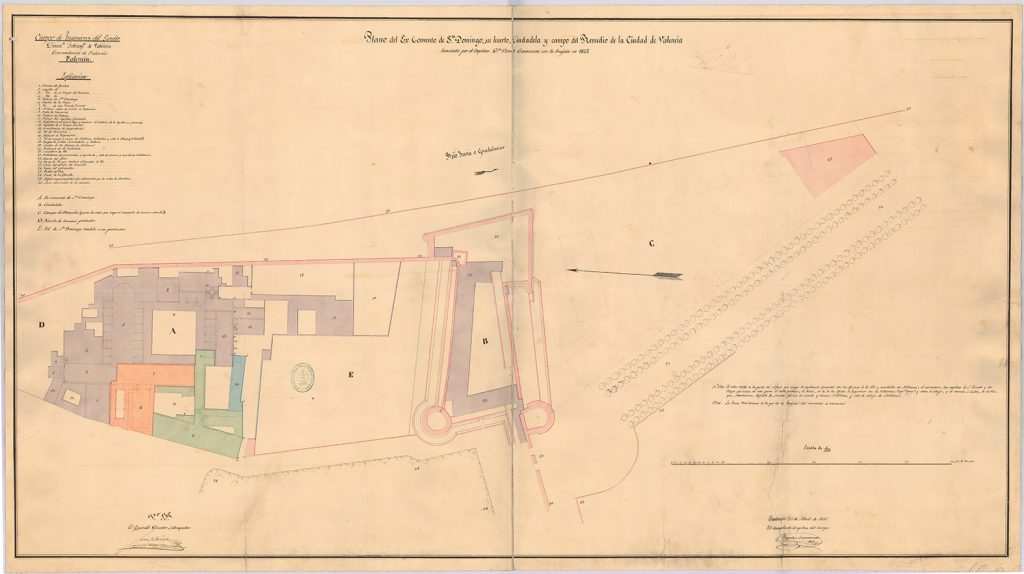

The refined simplicity of the architectural setting for royal piety represented by the chapel in the convent of Saint Dominic is consistent with the Dominican ideal of intense spirituality promoted by Saint Vincent Ferrer, the preacher and later saint who played a decisive role in both Alfonso’s father election as King of Aragon at Caspe (1412), and in the Observant reform implemented in Santa María la Real de Nieva (Segovia) under the patronage of Catherine of Lancaster and Maria of Aragon, Alfonso’s aunt and sister respectively.[56] Indeed, a chapel dedicated to Saint Vincent Ferrer after his canonisation was built in front of the entrance to the capilla de los Reyes, as can be observed in a plan of the convent from 1842 (Fig. 5.12). Never painted, the austere grey walls interrupted by the two oratories and the interior pulpit would have been suitable for concentration during personal prayer, outside of public ceremonies, with the help of a text such as the manuscript of Francesc Eiximenis’s Psalterium alias Laudatorium, lavishly illuminated by Pere Bonora and Leonard Crespí for Alfonso in 1443.[57] Dedicated to Antipope Benedict XIII, this Latin text, which complemented Eiximenis’s Vita Christi, became a challenging and enlightened collection of prayers and contemplation for popes and kings.[58]

A second indirect piece of evidence is provided by the transfer of the Crown of Aragon’s collection of relics from Barcelona to Valencia, where it was deposited in the cathedral in 1437, the very same year in which the chapel’s foundation is first recorded.[59] Although Alfonso needed to borrow money from the cathedral chapter and city authorities, it is difficult to imagine that he was indifferent to the symbolic value of this treasure amassed by his predecessors and augmented by him with the reliquary of Saint Louis of Toulouse, seized in Marseille in 1423.[60] It is worth remembering that among the relics delivered to Valencia Cathedral were such pieces as the Virgin’s Comb, the Holy Grail, a Veronica of the Virgin and a reliquary of Saint George, patron saint of the Crown of Aragon.[61] Some of these relics remained there on a temporary basis and were occasionally exhibited in the chapels of the Palau del Real, where the upper chapel was dedicated to Saint Catherine and the lower chapel to Saint Mary of the Angels.[62] For a short time, King Alfonso seemed keen to convey an image of piety in these chapels, enriching them with a crucifix of Flemish provenance (1425), acquired for 300 gold florins, and a ‘wooden oratory of some labour’ for 1,100 sous, to be maintained by carpenter Pasqual Esteve.[63]

It is perhaps not coincidental that building work started on the convent of Saint Dominic at a date very close to the transfer of relics to Valencia. An unexplained feature of the chapel is the presence of a side window, which could be identified as a hagioscope or squint and can still be seen on the southern wall of the chapel (Fig. 5.13). A hagioscope was deemed necessary when a chapel became a public space and so a separate oratory was constructed to enable members of the royal family to attend ceremonies.[64] After reforms and the demolition of most of the surrounding buildings in the convent, no oratory or private chamber connected to the squint has been preserved, but something similar survives in Maria of Castile’s oratory at the church of the Santísima Trinidad in Valencia where she was buried in 1458.[65] Moreover, a plan of the convent shows that this side of the chapel was in the immediate vicinity of the porter’s lodge, a space to receive laymen and adequate to accommodate a royal apartment if required (see Fig. 5.12).[66]

A second opening, now blocked by the sixteenth-century altarpiece, remains accessible via a spiral staircase and is linked to a room set over the groin vaults of the sacristy. An oblique round-arched doorway leads to the sacristy and the two intertwined spiral staircases, which in turn give access to the upper room and to an exterior pulpit. Such an arrangement would have been useful for displaying relics or the Holy Sacrament, permitting a few privileged faithful to venerate them and get a closer view. This is not inconceivable, since the king exhibited the relics in the palatine chapel in Barcelona on such occasions as the feast of Passio Imaginis (11 November) or of the Assumption (15 August), at least under Martin I.[67] In the palatine chapel of the Palau del Real, Maria of Castile presented the True Cross relic for public veneration.[68] In 1449, Alfonso paid the German artist Pere Staxar for a stone sculpture of the Passion for a royal chapel; this may have been in Naples but is more likely to have been in Valencia as the iconography was especially appropriate for a site where relics were displayed.[69]

The layout of the chapel was not dissimilar to the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris, with two lateral niches, a squint and stairs to an upper platform over the sanctuary.[70] Nor was it very different from the later and chronologically-closer example of Vincennes.[71] The interior of the chapel, with the lateral niches, would have ensured the visibility of the relics or Holy Sacrament in sharp contrast to the dark grey walls in the background. The unexpected lack of sculpted or painted décor, apart from the altarpiece, contributed to the uncanny nudity of the walls under the austere and yet spectacular diamond vault (Fig. 5.14). The question of whether the Eucharist or the relics from the royal treasure were displayed remains elusive, but it is certainly possible: the collection of sacra pignora in the palatine chapel included the Holy Grail, and Alfonso made use of the badge of the burning seat or ‘Siege Perilous’ (kept vacant for the knight who accomplished the quest in the Arthurian legend) at least from 1426 in Valencia, before conquering Naples, his victory usually identified with this symbol.[72] The royal chapel included valuable Marian relics, especially the Virgin’s Comb given by the Duke of Berry in 1394, as well as the Veronica, and the Trastámara dynasty reinforced its association with the Virgin Mary in Ferdinand’s reign.[73] The altarpiece, painted by Joan Reixach (1457–1463), showed the Virgin of the Expectation (Virgo expectans) flanked by Saints Ildefonso and John, patrons of King Alfonso and of his brother and successor Juan II. As well as Alfonso’s onomastic saint, Ildefonso was a distinguished defender of the virginity of Mary before and after Jesus’s birth.[74] Marian devotion and Eucharistic cult provided a public representation of the monarchy within an urban context in one of the major mendicant convents in Valencia, and were combined with more popular celebrations in local festivals, such as the royal entrances and Corpus Christi processions celebrated on a regular basis.[75] Court and city could converge in these festivals, sharing their devotion and experiencing the presence of the relics in Valencia as a true donation instead of a temporary deposit, bringing them from the royal residence to the capilla de los Reyes in Saint Dominic and, eventually, to the cathedral.

In chapter 189 of the novel Tirant lo Blanc, written by the knight Joan Martorell in Valencia while the capilla de los Reyes was under construction, the protagonist, who saves the Byzantine Empire from destruction, joins a tournament wearing on his helmet a crest with a comb and the Holy Grail ‘like the one conquered by Sir Galahad, the good knight’.[76] Already confined to the world of fiction, the ideal of a Crusade to rescue the imperial capital of Constantinople was no longer a royal priority, but might well have been meaningful at the time of the foundation of this chapel.[77] The royal chapel in Saint Dominic is undeniably a masterpiece of late Gothic architecture, but the patterns of intention for its function remain blurred and subject to further research. This was also one of a series of shrines where monarchic ideals of piety and proximity to the sacred could be made manifest: values of particular significance for a dynasty that made no claims to sacral kingship, but which nonetheless required a sense of royal sovereignty linked to holiness. To bolster Alfonso’s Mediterranean ambitions, it was therefore in the dynasty’s best interests to communicate the power and prestige of the king to other European kingdoms and Italian princedoms, and to a large and varied audience in a city with strong aspirations to be considered the new capital of the Crown of Aragon.[78]

Citations

[2] MS Additional 28962, British Library. On the manuscript see Francesca Español Bertran, ‘El salterio y libro de horas de Alfonso el Magnánimo y el cardenal Joan de Casanova’, Locus amoenus 6 (2002-2003): pp. 91-114; Josefina Planas, ‘Valence, Naples et les routes artistiques de la Méditerranée: Psautier-Livre d’Heures d’Alphonse le Magnanime’, in Christiane Raynaud (ed.), Des heures pour prier: Les livres d’heures en Europe méridionale du Moyen Age à la Renaissance (Paris: Léopard d’Or: Cahiers du Léopard d’Or 17, 2014), pp. 65-101; Josefina Planas Badenas, ‘El Salterio-libro de horas del rey Alfonso V de Aragón’, in Sophie Brouquet and Juan Vicente García Marsilla (eds.), Mercados del lujo, mercados del arte (Valencia: Publicacions de la Universitat de Valencia, 2015), pp. 211-37.

[3] Josep Vicent Boira (ed.), El Palacio Real de Valencia: los planos de Manuel Cavallero (1802) (Valencia: Ayuntamiento de Valencia, 2006).

[4] ‘y como tenemos por tradición dicen que fueron hechas para en ellas hazer dos sepulturas y en ellas poner los cuerpos de las dos personas reales de dichos dos reyes y como mudaron de parescer pusieron dos retablos, el uno del prendimiento del Señor en el guerto y el otro de Su Sanctissima Coronación’. Francisco Sala, Historia de la Fundación y cosas memorables del Real Convento de Predicadores de Valencia, Manuscript, Biblioteca Històrica de la Universitat de València, MS 163, pp. 16-17.

[5] Luis Arciniega García, ‘Arquitectura a gusto de su Majestad en los monasterios de San Miguel de los Reyes y Santo Domingo (s. XVI y XVII)’ in Francisco Taberner et al. (eds.), Historia de la ciudad, vol. 2, Territorio, sociedad y patrimonio (Valencia: ICARO-Universitat de València, 2002), pp. 186-204, esp. pp. 189-93.

[6] Luis Tramoyeres Blasco, ‘Un tríptico de Jerónimo Bosco en el Museo de Valencia’, Archivo de Arte Valenciano 1:3 (1915): pp. 87-102; Luisa Tolosa Robledo, María Teresa Vedreño Alba, Arturo Zaragozá Catalán, La Capella Reial d’Alfons el Magnànim de l’antic monestir de Predicadors de València I: Estudis (Valencia: Generalitat Valenciana, 1997); Noelia García Pérez, ‘Modelos de enterramiento, modelos de patronazgo: la Capilla de los Tres Reyes del convento de Santo Domingo de Valencia y los Marqueses del Zenete’, Imafronte 19-20 (2007-2008): pp. 63-74.

[7] Rita Costa-Gomes, ‘The Royal Chapel in Iberia: Models, Contacts, and Influences’, The Medieval History Journal 12:1 (2009): pp. 77-111.

[8] Francesca Español Bertran, ‘Calendario litúrgico y usos áulicos en la Corona de Aragón bajomedieval’, Studium Medievale: Revista de Cultura visual-cultura escrita 2 (2009): pp. 185-212.

[9] Francisco M. Gimeno et al. (eds.), Ordinacions de la Casa i Cort de Pere el Cerimoniós (Valencia: Publicacions de la Universitat de València, 2009), pp. 203-34, attests to the special attention given to the royal chapel and the festivals to be celebrated there.

[10] Johannes Vincke, ‘Das Patronatsrecht der aragonesischen Krone’, in Spanische Forschungen der Goerresgesellschaft: Gesammelte Aufsätze zur Kulturgeschichte Spaniens 12 (1955): pp. 55-95; Günther Röhfleisch, ‘Der Ausbau der Pfalzkapelle zu Valencia durch Peter IV von Aragón’, in Homenaje a Johannes Vincke (Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, 1963), 1: pp. 187-92; Johannes Vincke, ‘El derecho de patronato de la Corona de Aragón en el Reino de Valencia’, in Primer Congreso de Historia del País Valenciano (Valencia: Universitat de València, 1980), 2: pp. 837-49.

[11] Gimeno et al., Ordinacions, pp. 206-7; Alberto Torra Pérez, ‘Reyes, santos y reliquias. Aspectos de la sacralidad de monarquía catalano-aragonesa’, in XV Congreso de Historia de la Corona de Aragón (Jaca, 1993) (Zaragoza: Gobierno de Aragón, 1996), 1:3, pp. 495-517, esp. pp. 507-10; Español Bertran, ‘Calendario litúrgico’, pp. 193-9.

[12] On the limits of variability concerning the transmission of models, see Costa-Gomes, ‘The Royal Chapel in Iberia’, pp. 87-94.

[13] Perpignan: Marcel Durliat, ‘Les chateaux des Rois de Majorque’, Bol·letí de la Societat Arqueològica Lul·liana 41 (1985): pp. 47-56; Francesca Español Bertran, ‘Le programme architectural: un palais pour vivre et gouverner’; and Dany Sandron, ‘Chapelles palatines: succès d’un type architectural (XIIIe-XIVe siècles)’, in Olivier Passarrius and Aymet Catafau (eds.), Un palais dans la ville. Le Palais des rois de Majorque à Perpignan (Perpignan: Trabucaire, 2014), pp. 115-33 and 249-58. Naples: Xavier Barral i Altet ‘Alfonso il Magnanimo tra Barcellona e Napoli, e la memoria del Medioevo’, in Arturo Carlo Quintavalle (ed.), Medioevo: immagine e memoria (Milan: Electa, 2009), pp. 668-74, p. 655, for an explanation of Alfonso’s choice to maintain the old chapel in the new castle after his conquest of Naples in 1442; Bianca De Divitiis, ‘Castel Nuovo and Castel Capuano in Naples: The Transformation of Two Medieval Castles into “all’antica” Residences for the Aragonese Royals’, Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 76 (2013): pp. 441-74, here pp. 448, 459-61, for some fifteenth-century descriptions of the chapel and its decor.

[14] William Tronzo, The Cultures of his Kingdom: Roger II and the Cappella Palatina in Palermo (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997); Marco Rosario Nobile, ‘The Residences of the Kings of Sicily, from Martin of Aragón to Ferdinand the Catholic’, in Silvia Beltramo et al. (eds.), A Renaissance Architecture of Power. Princely Palaces in the Italian Quattrocento (Leiden-Boston: Brill, 2015), pp. 354-78.

[15] Miguel Sobrino González, ‘Barcelona. Las razones de una catedral singular’, Goya 307-308 (2005): pp. 197-214; Miguel Sobrino González, ‘Palacios catedralicios, catedrales palatinas’, Anales de Historia del Arte 23, núm. ext. 2 (2013): pp. 551-67, in particular, pp. 554-64.

[16] Costa-Gomes, ‘The Royal Chapel in Iberia’, pp. 78-87; José Manuel Nieto Soria, ‘Los espacios de las ceremonias devocionales y litúrgicas de la monarquía Trastámara’, Anales de Historia del Arte 23, núm. ext. 2 (2013): pp. 243-58; Javier Martínez de Aguirre, Arte y monarquía en Navarra, 1328-1425 (Pamplona: Gobierno de Navarra, 1987); María Narbona Cárceles, ‘La Capilla de los Reyes de Navarra (1387-1425): espacio de espiritualidad y de cultura en el medio cortesano’, in Carmen Erro Gasca and Íñigo Mugueta Moreno (eds.), Grupos sociales en la historia de Navarra, relaciones y derechos. Actas del V Congreso de Historia de Navarra (Pamplona: Gobierno de Navarra, 2002), 1: pp. 119-32.

[17] Francesca Español Bertran, ‘Artistas y obras entre la Corona de Aragón y el reino de Francia’, in María Concepción Cosmen et al. (eds.), El intercambio artístico entre los reinos hispanos y las cortes europeas en la Baja Edad Media (León: Universidad de León 2009), pp. 253-94, esp. pp. 267-79.

[18] Anna Maria Adroer i Tasis, ‘Algunes notes sobre la capella del Palau Major de Barcelona’, Anuario de Estudios Medievales 19 (1989): pp. 385-97; Torra Pérez, ‘Reyes, santos y reliquias’, pp. 508-11; Francesca Español Bertran, ‘La Santa Capella del rei Martí I l‘Humà i el seu context’, Lambard. Estudis d‘art medieval 21 (2009-2010): pp. 27-52, here pp. 42-52.

[19] Español Bertran, ‘Artistas y obras’, p. 279; Español Bertran, ‘La Santa Capella’, p. 44.

[20] Claudine Billot, Les Saintes Chapelles royales et princières (Paris: Éditions du Patrimoine, 1998); Laurent Vissiére, ‘L‘erection des Saintes-Chapelles (XIVe-XVe siècles)’, in Élisabeth Crouzet-Pavan and Jean-Claude Maire Vigueur (eds.), L‘art au service du prince. Paradigme italien, expériences européennes (vers 1250-vers 1500) (Rome: Viella 2015), pp. 116-29, esp. pp. 137-9.

[21] David Nogales Rincón, ‘Las capillas y capellanías reales castellano-leonesas en la baja Edad Media (siglos XIII-XV): algunas precisiones institucionales’, Anuario de Estudios Medievales 35:2 (2005): pp. 737-66, esp. pp. 738-48; David Nogales Rincón, ‘Rey, sepulcro y catedral. Patrones ideológicos y creación artística en torno al panteón regio en la Corona de Castilla (1230-1516)’, in Maria Dolores Teijeira et al. (eds.), Reyes y prelados. La creación artística en los reinos de León y Castilla (1050-1500) (Madrid: Sílex, 2014), pp. 257-82.

[22] Español Bertran, ‘Calendario litúrgico’, pp. 189-93; Francesca Español Bertran, ‘Formas artísticas y espiritualidad. El horizonte franciscano del círculo familiar de Jaime II y sus ecos funerarios’, in Isabel Beceiro Pita (ed.), Poder, piedad y devoción: Castilla y su entorno (siglos XII-XV) (Madrid: Sílex, 2014), pp. 389-422.

[23] Fernando Chueca Goitia, Casas reales en monasterios y conventos españoles (Madrid, Xarait: 1982).

[24] Maria Rosa Terés, ‘El Palau del Rei Martí a Poblet: una obra inacabada d‘Arnau Bargués i Françoi Salau’, D‘Art 16 (1990): pp. 19-40.

[25] Amadeo Serra Desfilis and Matilde Miquel Juan, ‘La capilla de San Martín en la Cartuja de Valldecrist: construcción, devoción y magnificencia’, Ars longa 18 (2009): pp. 65-80.

[26] José María Madurell Marimón, Mensajeros barceloneses en la Corte de Nápoles de Alfonso V de Aragón (1435-1458) (Barcelona: Escuela de Estudios Medievales, 1963), pp. 429-30, cited by Francesca Español Bertran, Els escenaris del rei: art i monarquia a la Corona d’Aragó (Manresa: Fundació Caixa Manresa, 2001), p. 269.

[27] Español Bertran, Els escenaris, p. 114.

[28] Español Bertran, ‘Calendario litúrgico’, p. 189.

[29] Español Bertran, ‘Calendario litúrgico’, p. 195.

[30] Serra Desfilis, Miquel Juan, ‘La capilla de San Martín’, p. 69; Español Bertran, ‘La Santa Capella’, pp. 29-30 (Poblet) and 33 (Valldecrist). Español Bertran connects this royal gallery to the main church instead of to the Chapel of Saint Martin.

[31] Francesc Eiximenis, Scala Dei. Devocionari de la reina Maria (Barcelona: Publicacions de l’Abadia de Montserrat, 1985), p. 9: see Español Bertran, ‘El salterio y libro de horas’, p. 105n96.

[32] Albert G. Hauf, D’Eiximenis a sor Isabel de Villena: aportació a l’estudi de la nostra cultura medieval (València-Barcelona: Universitat de València-Abadia de Montserrat, 1990), pp. 219-300; Núria Silleras-Fernández, Power, Piety and Patronage in Late Medieval Queenship: María de Luna (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008), pp. 139-60; Español Bertran, ‘Calendario litúrgico’, p. 189.

[33] Francesca Español Bertran, ‘El tesoro sagrado de los reyes en la Corona de Aragón’, in Maravillas de la España medieval. Tesoro sagrado y monarquía (Valladolid: Junta de Castilla y León, 2001), p. 273.

[34] Español Bertran, ‘La Santa Capella’, pp. 27-52.

[35] Torra Pérez, ‘Reyes, santos y reliquias’, p. 516.

[36] Alan Ryder, Alfonso the Magnanimous, King of Aragon, Naples and Siclily, 1396-1458 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1990), pp. 45-174; Rafael Narbona Vizcaíno, ‘Alfonso el Magnánimo, Valencia y el oficio de Racional’, in Giovanni d’Agostino (ed.), XVI Congresso di Storia della Corona d’Aragona: La Corona d’Aragona ai tempi di Alfonso il Magnanimo (Naples: Paparo Edizioni, 2001), 1: pp. 593-617; Juan Vicente García Marsilla, ‘Avalando al rey: Préstamos a la Corona y finanzas municipales en la Valencia del siglo XV’, in Manuel Sánchez Martínez and Denis Menjot (eds.), Fiscalidad de Estado y fiscalidad municipal en los reinos hispánicos medievales (Madrid: Casa de Velázquez, 2006), pp. 377-90.

[37] Salvador Carreres Zacarés, Ensayo de una bibliografía de libros de fiestas celebradas en Valencia y su antiguo Reino (Valencia: Vives Mora, 1925), 1: pp. 66-9; 2: pp. 96-109. For the Palau del Real, see Mercedes Gómez-Ferrer, ‘La reforma del Real Vell de Valencia en época de Alfonso el Magnánimo’, Lexicon: Storie e architettura in Sicilia 8 (2009): pp. 7-22.

[38] Juan Vicente García Marsilla, ‘El poder visible: demanda y funciones del arte en la corte de Alfonso el Magnánimo’, Ars longa 7-8 (1996-1997): pp. 33-47; Juan Vicente García Marsilla, Art i societat a la València medieval (Catarroja: Afers, 2011), pp. 239-72.

[39] Español Bertran, ‘El tesoro sagrado’, p. 280; Torra Pérez, ‘Reyes, santos y reliquias’, p. 516.

[40] Caroline Bruzelius, Preaching, Building and Burying. Friars in the Medieval City (New Haven-London: Yale University Press, 2014), pp. 124 and 129.

[41] Arturo Zaragozá Catalán, ‘La Capilla Real del antiguo Monasterio de Predicadores de Valencia’, in Tolosa Robledo et al., La Capella Reial I: Estudis, pp. 14-59; Pablo Navarro Camallonga and Enrique Rabasa Díaz, ‘La bóveda de la capilla real del antiguo convento de Santo Domingo de Valencia. Hipótesis de trazas de cantería con la aproximación al arco’, in Enrique Rabasa Díaz et al. (eds.), Obra Congrua (Madrid: Instituto Juan de Herrera, 2017), pp. 253-64.

[42] Zoë Opacic, Diamond Vaults. Innovation and Geometry in Medieval Architecture (London: Architectural Association, 2005), p. 10.

[43] Arturo Zaragozá Catalán, ‘Cuando la arista gobierna el aparejo: bóvedas aristadas’, in Amadeo Serra Desfilis (ed.), Arquitectura en construcción en Europa en época medieval y moderna (Valencia: Universitat de València, 2010), pp. 187-224.

[44] José Luis Jiménez Salvador and Ferran Arasa i Gil, ‘Procesos de expolio y reutilización de la arquitectura pública romana en el territorio valenciano’, in Luis Arciniega García and Amadeo Serra Desfilis, Recepción, imagen y memoria del arte del pasado (Valencia: Universitat de València, 2018), pp. 47-69.

[45] Zaragozá Catalán, ‘La Capilla Real’, pp. 34-43; Javier Martínez de Aguirre, ‘Imagen e identidad en la arquitectura medieval hispana: carisma, filiación, origen, dedicación’, Codex Aquilarensis 31 (2015): pp. 121-50, esp. pp. 124-6.

[46] Robert I. Burns, The Crusader Kingdom of Valencia (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1967), 1: pp. 204-7.

[47] For the sources, see Luisa Tolosa Robledo, María Carmen Vedreño Alba, La Capella Reial d’Alfons el Magnànim de l’antic monestir de Predicadors de València II: Documents (Valencia: Generalitat Valenciana, 1996).

[48] Archivo del Reino de Valencia, Bailía, ápocas, microfilm 1629, fol. 338, 30 October 1443, as mentioned by Luisa Tolosa Robledo and María Carmen Vedreño Alba, ‘La Capella del Rei Alfons el Magnànim al Monestir de Sant Domènech de València’, in La Capella Reial I: Estudis, p. 63.

[49] Traité sur l’oraison mentale, Brussels, manuscript 9092, fol. 9r, miniature by Jean Le Tavernier, 1454, Bibliothèque Royale Albert Ier.

[50] Francesca Español Bertran, ‘Encuadres arquitectónicos para la muerte: de lo ornamental a lo representativo. Una aproximación a los proyectos funerarios del tardogótico hispano’, Codex Aqularensis 31 (2015): pp. 93-119.

[51] Daniel Benito Goerlich, El Real Monasterio de la Santísima Trinidad de Valencia (Valencia: Consell Valencià de Cultura, 1998), pp. 53-7.

[52] Zaragozá Catalán, ‘La Capilla Real’, pp. 44-7. George E. Street, Some Account of Gothic Architecture in Spain (London: J. Murray, 1865), p. 286, George E. Street had heard of it but could not visit the chapel.

[53] Psalter and Hours, Dominican use, known as the Prayerbook of Alfonso V of Aragón, manuscript Add MS 28962, British Library, http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Add_MS_28962.

[54] Español Bertran, ‘El salterio y libro de horas’, pp. 104-7.

[55] Antonio Beccadelli, ‘De dictis et factis Alphonsi regis Aragónum’, MS 445, fols. 77r-79r, Biblioteca Històrica de la Universitat de València, with particular mention of the ceremony on Maundy Thursday; see also Español Bertran, ‘El salterio y libro de horas’, p. 94; Planas Badenas, ‘El Salterio-Libro de Horas’, pp. 214-32.

[56] Philip Dayleader, Saint Vincent Ferrer. His World and Life: Religion and Society in Late Medieval Europe (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016); Diana Lucía Gómez-Chacón, ‘Reinas y predicadores: el Monasterio de Santa María la Real de Nieva en tiempos de Catalina de Lancaster y María de Aragón (1390-1445)’, in Teijeira et al. (eds.), Reyes y prelados, pp. 325-40; Gómez-Chacón, ‘Arte y reforma dominicana en el siglo XV: Nuevas perspectivas de estudio’, Erasmo. Revista de historia bajomedieval y moderna 4 (2017): pp. 87-106. For observance during the fifteenth century, see Emilio Callado Estela and Alfonso Esponera Cerdán, ‘1239-1835: Crónica del Real Convento de Predicadores de Valencia’, in El Palau de la Saviesa. El Reial Convent de Predicadors de València i la Biblioteca Universitària (Valencia: Universitat de València, 2005), p. 133.

[57] MS 726, Biblioteca Històrica de la Universitat de València. Amparo Villalba Dávalos, La miniatura valenciana en los siglos XIV y XV (Valencia: Alfonso el Magnánimo, 1964), pp. 91-3, 142-5, 233-4, 237-40; Josefina Planas Badenas, ‘Los códices ilustrados de Francesc Eiximenis: análisis de su iconografía’, Anuario del Departamento de Historia y Teoría del Arte 9-10 (1997-1998): pp. 73-90, esp. pp. 77-8.

[58] Francesc Eiximenis, Psalterium alias Laudatorium, (ed.) Curt J. Wittlin (Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, 1988); Albert G. Hauf i Valls, ‘El “Psalterium alias Laudatorium” i la “Vita Christi” de Francesc Eiximenis, obres complementàries?’, in Miscel·lània Joan Bastardas, vol. 1, Estudis de Llengua i Literatura Catalanes XVIII (Barcelona: Abadia de Montserrat, 1989), pp. 205-29.

[59] Tolosa Robledo, Vedreño Alba, ‘La Capella del Rei’, pp. 62-3.

[60] Ryder, Alfonso the Magnanimous, pp. 114 and 117.

[61] Peregrín-Luis Llorens Raga, Relicario de la catedral de Valencia (Valencia: Alfonso el Magnánimo, 1964); Miguel Navarro Sorni, ‘Pignora sanctorum. En torno a las reliquias, su culto y las funciones del mismo’, in Joan J. Gavara (ed.), Reliquias y relicarios en la expansión mediterránea de la Corona de Aragón. El Tesoro de la Catedral de Valencia (Valencia: Generalitat Valenciana, 1998), pp. 95-133; Catalina Martín Lloris, ‘Las reliquias de la Capilla Real en la Corona de Aragón y el Santo Cáliz de la Catedral de Valencia (1396-1458)’ (PhD diss., Universitat de València, 2004).

[62] Amadeo Serra Desfilis, ‘“Cort e Palau de Rey”. The Real Palace of Valencia in the Medieval Epoch’, Imago Temporis. Medium Aevum 1 (2007): pp. 121-48, here p. 137.

[63] José Sanchis Sivera, ‘La escultura valenciana en la Edad Media’, Archivo de Arte Valenciano 10 (1924): 16-17; Luis Fullana Mira, ‘El Palau del Real’, Cultura Valenciana 2 (1927): 153-6; García Marsilla, Art i societat, p. 252.

[64] Pierre-Yves Le Pogam, ‘The Hagioscope in the Princely Chapels in France from the Thirteenth to the Fifteenth Century’, in Jiri Fajt (ed.), Court Chapels of the High and Late Middle Ages and their Artistic Decoration (Prague: National Gallery of Prague, 2003), pp. 171-8.

[65] Arturo Zaragozá Catalán, ‘Real Monasterio de la Trinidad’, in Joaquín Bérchez (ed.), Valencia, arquitectura religiosa (Valencia: Generalitat Valenciana, 1995), p. 144; Benito Goerlich, El Real Monasterio, p. 89.

[66] Archivo General Militar, Madrid, B-1-21, Plan of the former Convent of Saint Dominic (1847). This area (number 11 in the plan) had been rebuilt between 1789 and 1800 as part of the new façade project, whereas Capilla de los Reyes is identified by number 6.

[67] Torra Pérez, ‘Reyes, santos y reliquias’, pp. 510-11; Español Bertran, ‘Calendario litúrgico’, p. 210.

[68] Fullana, ‘El Palau del Real’, pp. 153-6; Serra Desfilis, ‘The Real Palace’, p. 137.

[69] Sanchis Sivera, ‘La escultura valenciana’, p. 22.

[70] Peter Kovâc, ‘Notes on the Description of the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris from 1378’, in Fajt (ed.), Court Chapels, pp. 162-70, here, p. 163; Meredith Cohen, The Sainte-Chapelle and the Construction of Sacral Monarchy (Cambridge-New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015), pp. 159-64

[71] For Vincennes, see Odette Chapelot et al., ‘Un chantier et son maître d’oeuvre: Raymond du Temple et la Sainte-Chapelle de Vincennes’, in Odette Chapelot (ed.), Du projet au chantier. Maîtres d’ouvrage et maîtres d’oeuvre aux XIVe-XVIe siècles (Paris: École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, 2001), pp. 433-88. For its relationship with the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris and successive imitations in Aachen and Westminster, see Dany Sandron, ‘La culture des architectes de la fin du Moyen Âge. À propos de Raymond du Temple à la Sainte-Chapelle de Vincennes’, Comptes rendus des séances de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres 150: 2 (2006): pp. 1255-79, esp. pp. 1260-79. Connections between decorative sculpture in late fourteenth-century France and the Crown of Aragon have been observed by Maria Rosa Terés in ‘La escultura del Gótico Internacional en la Corona de Aragón: los primeros años (ca. 1400-1416)’, Artigrama 26 (2011): pp. 147-81.

[72] García Marsilla, ‘El poder visible’, pp. 39-40; first mentioned in the sources in 1426: Rafael Beltrán Llavador, ‘Los orígenes del Grial en las leyendas artúricas. Interpretaciones cristianas y visiones simbólicas’, Tirant: Butlletí informatiu i bibliogràfic 11 (2008): pp. 19-54.

[73] Francesc Ruiz i Quesada, ‘Els primers Trastàmares. La legitimació mariana d’un llinatge’, in Maria Rosa Terés (ed.), Capitula facta et fermata. Inquietuds artístiques en el Quatre-cents (Valls: Cossetània, 2011), pp. 71-112, esp. pp. 99-101.

[74] For an eighteenth-century description of the old altarpiece, displaced and moved to the chapter house, see José Teixidor, Capillas y sepulturas del Real Convento de Predicadores de Valencia (Valencia: Acción Bibliográfica Valenciana, 1949) 2: pp. 418 and 424.

[75] Rafael Narbona Vizcaíno, Memorias de la Ciudad. Ceremonias, creencias y costumbres en la historia de Valencia (Valencia: Ayuntamiento de Valencia, 2003), pp. 69-100.

[76] Beltrán Llavador, ‘Los orígenes del Grial’, pp. 44-6.

[77] Joan Molina Figueras, ‘Un trono in fiamme per il re. La metamorfosi cavalleresca di Alfonso il Magnanimo’, Rassegna storica salernitana, 28: 56 (2011): pp. 11-44, here pp. 28-30.

[78] Andrea Longhi, ‘Palaces and Palatine Chapels in 15th-Century Italian Dukedoms: Ideas and Experiences’, Beltramo et al. (eds.), A Renaissance Architecture of Power, pp. 82-104.

DOI: 10.33999/2019.49