In December of 1502 Elizabeth of York, the heavily pregnant wife of King Henry VII, paid six shillings and eight pence to a monk who had just brought her ‘our Lady gyrdelle’.[1] This relic, ‘which weomen with chield were wont to girde with’, was just one of many such belts and girdles, often associated with the Virgin Mary, that were owned by English churches and believed to provide protection during childbirth.[2] As well as actual girdle relics, medieval women could rely on manuscript birth girdles: parchment rolls that mimicked the relics and served the same purpose. These manuscripts, like the girdles they imitated, would be wrapped around the pregnant woman’s womb either in the weeks leading up to the delivery or during labour itself.

At least eight English manuscript rolls dating from the late fourteenth century to the early sixteenth century, as well as one printed sheet from 1533, are described as ‘birth girdles’ in current scholarship (see Appendix).[3] Here, I argue that the term has been too widely applied, creating unfounded assumptions about the gendered nature of the manuscripts in question. While these rolls could have been used for amuletic protection during childbirth, the term ‘birth girdle’ also implies a specific physical interaction between the manuscript and the expectant mother for which there is little evidence. It emphasises only one of the rolls’ possible functions, obscuring their more general protective and devotional role and placing unnecessary emphasis on a single facet of their use.

In making this argument, I do not intend to reject the conceptual category of ‘birth girdle’. There is strong evidence for the existence of manuscripts that were used as girdles for the purpose of protection during childbirth. For example, one early thirteenth-century remedy reads:

Ad difficultatem partus ista tria nomina pone. in alico cingulo et da

mulieri ut precingat se de hoc cingulo. Vrnum. BvrNVM. BlizaNVM.

For a difficult birth put these three names on a girdle and give it to

the woman to gird herself with that girdle. Vrnum. BvrNVM.

BlizaNVM.[4]

There is nothing to suggest, however, that most of the surviving ‘birth girdle’ manuscripts would have been used as girdles, or that those that were would have been used exclusively in this manner.

Eight of the nine artifacts described as birth girdles contain vernacular and Latin prayers to saints Quiricus and Julitta, which Mary Morse and Scott Gwara have called ‘the defining textual features of the English birth girdle tradition.’[5] The presence of these prayers on a manuscript with a roll or sheet format has been sufficient to identify a ‘birth girdle’. According to Jacobus de Voragine’s immensely popular Legenda Aurea, Julitta and her three-year-old son Quiricus were both martyred in the third century after Julitta refused to sacrifice to the Roman gods (fig. 9.3). Despite his young age Quiricus fought against the governor who ordered Julitta’s death, and in some versions of the legend even testified to his own Christian faith.[6] This story was declared to be false and heretical in the fifth century, but the Legenda Aurea and its subsequent vernacular translations popularised the legend across Europe.[7] Nothing in this vita, except perhaps Quiricus’s young age, suggests a particular connection with childbirth. Mary Morse has noted that ‘no legendary account refers to saints Quiricus and Julitta as protectors of women in childbirth’; nor are they associated with childbirth in any of the surviving records from English churches or monastaries dedicated to them.[8] Despite this, the presence of prayers to Quiricus and Julitta in so many manuscript ‘birth girdles’ has led her to identify a medieval English childbirth cult associated with these saints.[9]

The Quiricus and Julitta prayers in the ‘birth girdles’, I argue, are linked not to childbirth, but to the amuletic image of the measured cross with which they appear. The English text referring to Quiricus and Julitta in the ‘birth girdles’ usually appears wrapped around a tau cross, whose length can be multiplied by fifteen to give the height of Christ (fig. 9.4).[10] The text describes the cross’s protective virtues, in language which varies somewhat from one manuscript to another.[11] In Beinecke MS 410, which contains one of the shorter lists of benefits, it guarantees that on the day that someone looks at the measured cross, blesses him or herself with it, or carries it devoutly, he or she will be protected from wicked spirits, enemies, thunder, lightning, wind, bad weather, weapons, and death without confession. It also promises that:

yf a woman haue this crosse on hyr when she trauelith of chylde

[th]e chylde and she shall be departyd without peryll of dethe be

the grace of god.[12]

The text claims that the Quiricus and Julitta asked God to provide these protective benefits, explaining that:

Saynt Cyryace and saynt Julite hys modyr desyryd thys petycyon of

god and he graunted it them. As it is regystred in Rome at saynt

John latynes.[13]

All eight ‘birth girdles’ that include the Quiricus and Julitta prayer similarly state that the saints asked God to grant the virtues attached to the measured cross.

In all of the supposed birth girdles in which it appears, this English text introduces the Latin prayers to Quiricus and Julitta. In most cases, the Latin prayers also refer specifically to the power of the cross and its measure, asking God to grant the speaker the virtue of Christ’s glorious measure and venerable cross.[14] Both of the texts shared by the ‘birth girdles’, therefore, are linked specifically to the many protective qualities of this particular image.[15] This is most evident in Wellcome MS 632 (figs 9.1 and 9.11). In the other examples, the image and the English text appear together. In the Wellcome manuscript, however, the English text that refers to the image appears first, followed by the Latin prayer to Quiricus and Julitta, and finally by the cross itself surrounded by the instruments of the Passion (fig. 9.5). The separation of the English text explaining the virtues of the cross from the image to which it refers implies that the English, the Latin, and the image of the cross could all be seen as part of a single apotropaic unit carrying a wide range of protective benefits. Prayers to Quiricus and Julitta occur elsewhere without reference to the measured cross, but here as well the saints are invoked for general protection rather than protection during childbirth.[16]

The manuscript that most closely links Quiricus and Julitta with childbirth is the Neville of Hornby Hours. This manuscript, owned by Isabel de Neville of Hornby manor in North Lancashire, was probably copied in London around the years 1335 to 1340.[17] On folios 24r–25r there is a prayer to the Virgin, introduced by an Anglo-Norman rubric that instructs the reader to use the prayer if milk leaks from her breasts during pregnancy (figs 9.6 and 9.7).[18] The prayer to Quiricus and Julitta appears shortly afterwards, on folio 26v. Its rubric reads:

[S]i vous estes en ascun anguisse ou travaille denfaunt dites cest

orisoun e[n]swant ou lanteine et le verset . en lonur de dieu et de

seint marie et de seinte cirice et iulicte et vous serrez [t]ost eyde.

If you are in any distress or in labour, say this prayer following or

the antiphon and the versicle in the honour of God and of St Mary

and of St Quiricus and Julitta and you will soon be helped.

While this rubric certainly emphasises childbirth, it also promises aid in any distress. The presence of the earlier specifically pregnancy-related prayer might also suggest that the focus on childbirth here is more a reflection of the interests of the manuscript compiler than of the saints themselves.

In both rolls and codices, therefore, Quiricus and Julitta are primarily invoked for general protection, not as part of a specific childbirth cult. Their prayers and suffrages appear in manuscript ‘birth girdles’ only in connection with the measured cross and its wide range of protective benefits. The scholarly identification both of the childbirth cult of Quiricus and Julitta and of the ‘birth girdles’ themselves is, therefore, circular. Quiricus and Julitta have been identified as childbirth saints primarily because they are frequently invoked in ‘birth girdle’ prayers, while the rolls themselves are identified as birth girdles because they contain prayers invoking Quiricus and Julitta. There appears to be no reason to believe that a childbirth cult of Quiricus and Julitta existed. Consequently, there is no reason that rolls referring to Quiricus and Julitta should necessarily be associated with childbirth. We must look elsewhere for support for the ‘birth girdle’ identification.

Without the support of the prayers to Quiricus and Julitta just two rolls, Wellcome MS 632 and Takamiya MS 56 (figs 9.2 and 9.12), are persuasive examples of birth girdles. In five of the other supposed ‘birth girdles’ the text associated with the measured cross is the only reference to childbirth that appears.[19] None of these ‘girdles’ makes any specific reference to girdling the woman with the roll. Beinecke MS 410 and the printed sheet state only that the woman should have the measured cross on her, while the remaining three manuscripts instruct the reader to lay the cross on the woman’s womb or body. The same instructions are given when the image appears in codices. For example, the measured cross in the Bodleian Library’s Bodley MS 177 (a codex) instructs the reader that ‘yff a woman traueyle on chylde ley thys a poun hyr’. [20] This demonstrates that the roll format is unrelated to the power of the image.

The two remaining manuscripts, Harley Roll T.11 and the roll held at the Redemptorist Archives of the Baltimore Province, contain other references to childbirth, but neither gives explicit instruction to use the roll as a girdle. Harley T.11 includes a charm for a quick and painless delivery, which is a combination of two very common charms: the palindrome ‘sator arepo tenet opera rotas’, used in English childbirth charms since at least the eleventh century, and the peperit charm, which lists a series of miraculous Biblical births.[21] Its instructions tell the reader to place the text of the charm in the woman’s hand, without suggesting that the roll should be wrapped around her. It also includes a life-size image of the wound in Christ’s side, accompanied by a text which promises a series of benefits much like those attached to the measured cross.[22] The measured side wound is common both in rolls and in codices, and most of its benefits could be received by carrying the image (fig. 9.8).[23] For a woman to be protected during labour, however, she need only ‘haue sayne [seen] the sayd mesur’ on that day. Although Harley T.11 contains three promises of safety in childbirth, none asks for the roll to be used as a girdle. The numerous other texts and images in this manuscript, promising protection against dangers or inconveniences including thunder, insomnia, false witnesses, pestilence, and poverty, demonstrate that it could have been used in a wide variety of situations.

The Baltimore roll, like Harley T.11, contains more than one reference to protection in childbirth, but no evidence that a woman would have interacted with it in the manner implied by the term ‘birth girdle’. Its main text is the Middle English devotional poem ‘O Vernicle’.[24] This poem was frequently copied in roll format, and sometimes circulated with an indulgence offering a range of amuletic benefits to those who looked devoutly at its illustrations of the instruments of the Passion. The version of the indulgence which appears in the Baltimore roll, and in another six of the twenty manuscripts of the poem, states that ‘to women it is meke and mylde / When [th]ai trauailen of her childe’.[25] In the Baltimore roll this indulgence is immediately followed by a version of the measured cross text, including a promise of safety in childbirth. In this version, which differs from the text in the other ‘birth girdle’ rolls, protection of various kinds is granted ‘what day [th]at [th]ou blessest [th]e thryes [th]er with in [th]e name of god and of his lenght’.[26] There is no mention of girdling the woman with the roll, and both references to childbirth appear as standard elements within longer lists of possible benefits. Although the manuscript may have been made with a female owner in mind—unusually, its Latin uses feminine forms—it seems to have been intended for general protective use.[27] This manuscript, like the other ‘birth girdles’ already discussed, might be more fruitfully explored in the context of indulgenced images and protective prayers than purely in the context of childbirth.

Ownership evidence also suggests that these rolls were not primarily intended as birth girdles. Four of the manuscripts contain references to medieval owners or makers: all of these were men. Harley 43.A.14, a small roll that contains only the measured cross and related prayers to Quiricus and Julitta, was written for the use of a man named William, whose name is inserted into its prayers.[28] Beinecke MS 410 was written for a man called Thomas, who is named as the beneficiary of the prayer to Quiricus and Julitta, and perhaps depicted in a donor portrait at the head of the roll (fig. 9.9).[29] British Library Additional MS 88929 was owned by the young Henry VIII. His royal badges are included at the head of the roll, and at some point before his accession to the throne he inscribed it to one of the Gentlemen of his Privy Chamber, William Thomas (fig. 9.10).[30] This ownership evidence, particularly where it is included in the body text of the roll, indicates that the rolls were made with particular male users in mind. Despite its promise of safety in childbirth, the image of the measured cross clearly appealed to men as well as women.

The evidence of MS Glazier 39 is slightly more complicated. It was copied by a man named Percival, a canon of the Premonstratensian Abbey of Coverham, though he was not necessarily its owner.[31] The Latin prayer to the Virgin in this roll does use the female forms ‘ego misera peccatrix’ [I, a miserable (female) sinner] and ‘michi indigne famule tue’ [to me, your unworthy (female) servant]. However, other prayers use plural or masculine forms, leading Don C. Skemer to suggest that the roll ‘could have been used devotionally and amuletically for the benefit of family and household.’[32] The prayer to Quiricus and Julitta, which Mary Morse identifies as ‘the most telling evidence’ for women’s usage, uses the masculine form ‘tribue michi famulo tuo’ [grant me, your (male) servant].[33] This troubles such a gendered attribution.[34]

As Quiricus and Julitta appear to have been invoked for general protection, not for childbirth specifically, these rolls can largely be associated with childbirth only on the basis of a standard set of promises accompanying the image of the measured cross. Their roll format plays no part in the protective power of that image or any others they carry, and their identifiable owners were male. In considering these manuscripts as amuletic rolls rather than ‘birth girdles’, we undo false assumptions about how they were used and open ourselves to new and broader understandings of their possible functions. Importantly, this is also true for the two persuasive examples of birth girdles, Wellcome MS 632 and Takamiya MS 56.

Wellcome MS 632, which has been described as functioning ‘exclusively as a birth girdle’, is a heavily worn parchment roll 330 cm long (even with some material missing at the head of the roll) and only 10 cm wide.[35] An inscription on the back of the roll associates the length of the manuscript with the heights of Christ and the Virgin Mary, claiming first that it is ‘a mesu[re] of the length off ou[re Lord J]esu’, and then reading ‘Thus moche more ys oure lady seynt mary lenger’ (fig. 9.13). The inscription also confirms that the roll was used, or was intended to be used, as a birth girdle. Running along the length of the roll is a text that guarantees benefits such as safety in battle and protection from devils, fire, wrongful judgment, and pestilence. It ends:

And yf a woman travell wyth chylde gyrdes thys mesure abowte

hyr wombe and she shall be safe delyvyrd wythowte parelle and

the chylde shall have crystendome and the mother puryfycatyon.

These instructions specify that the woman should gird herself with the manuscript. Clearly, this physical interaction goes beyond simply reading the texts or observing and touching the images.

Takamiya MS 56 is similarly narrow at just 8 cm wide and 173 cm long, despite now missing at least one membrane.[36] This format is relatively unusual. All of the ‘birth girdles’ are narrow compared to other English manuscript rolls, but most are either significantly wider than these two, or significantly shorter.[37] The long, narrow shape of these rolls mimics the actual girdle relics held by medieval churches, for instance the Sacra Cintola in Prato. Takamiya MS 56 takes this identification further: the single line of text on the dorse is contained within a brown ink border decorated with white circles, perhaps mimicking the design of a belt, emphasising the manuscript’s metaphorical transformation into the girdle relic (fig. 9.14). As in Wellcome MS 632, the inscription on the dorse of Takamiya MS 56 links the length of the roll with the Virgin’s height, and offers protection from peril, tribulation, and disease. It states that ‘a woman that ys quyck wythe chylde gerde hyr wythe thys mesure and she shall be safe fro all maner of perilles’ (fig. 9.15).

The orientation of the dorse text of both rolls also aligns the manuscripts with the relic. While the texts on the front of Wellcome MS 632 and Takamiya MS 56 run down the roll as is typical in the Middle Ages, the texts on the back run lengthways along it. In order to read the instructions explaining how to use the girdle, therefore, the user must change the orientation of the manuscript so that it is fully unrolled and held horizontally, like a belt or girdle (fig. 9.16). From this position, the manuscript is ready to be wrapped around the woman. As well as aligning the manuscripts with the Virgin conceptually the dorse inscriptions use the reader’s interaction with the text to physically align the rolls with the relic they imitate.

Medieval charms make use of similar conceptual strategies of alignment to create healing power. Historiolae, short stories which provide a mythological narrative echoing the desired magical result, function in part by collapsing the perceived distance between Biblical figures and the present crisis.[38] Similarly, the combination of the roll format and the visual identification between manuscript and relic serves to collapse the distance between the secular and sacred worlds. In the common ‘super Petram’ charm, for example, the historiola narrates a meeting between Christ and St Peter in which St Peter tells Christ that he has a toothache, and Christ commands the worm causing the toothache to leave. In Christ’s words, however, the name of the medieval patient is substituted for the name of St Peter. The practitioner ventriloquises the words of Christ and, as Edina Bozóky argues, ‘the sick person enters the mythic world of the narrative incantation’.[39]

The same effect can be achieved in written, as well as spoken, charms. One blood-stanching charm, used in England at least from the Anglo-Saxon period until the end of the fifteenth century, consists in part of writing the name ‘Beronix‘ (for a man) or ‘Beronixa’ (for a woman) on the patient’s forehead in his or her own blood.[40] Berenice, or Veronica, is the name that medieval Christians associated with the woman healed of bleeding in the Gospels.[41] The charm’s text identifies the patient with the Biblical figure, blurring the boundaries between contemporary and Biblical narratives in an effort to cure the patient. In all of these examples, the charms draw power from a shifting of identification: between the practitioner and Christ, between the patient and the Biblical figures, and between the ordinary parchment and the girdle relic. The birth girdles function both because of their physical format and because of their ability to create associations between Biblical and contemporary time.

Wellcome MS 632 and Takamiya MS 56 share a number of texts and images that do not appear in the other so-called ‘birth girdles’. Above the image of the nails in both rolls is a prayer beginning ‘Omnipotens sempiterne deus qui humanum genus quinque vulneribus filij tui’ [All-powerful, eternal God, who [redeemed] mankind through the five wounds of your son]. Although the text in Wellcome MS 632 is almost illegible, by comparing the two texts it is clear that the prayer is the same. Both contain a prayer beginning ‘Ave domina sancta maria’ [Hail holy lady Mary] and a rubric, apparently unique to these two manuscripts, connecting it with Tewkesbury (fig. 9.17). As this text has not previously been considered legible in Wellcome MS 632, I transcribe the English rubric here in full:

Oracio beate marie [W]ho so devoutly say[th] thys prayer here

folowynge shall [have] xj thousand yerys off pardon and he shall se

oure blessyd lady as many tymys as he hath used the sayd prayer

whych was brought to an holy hermyte by saynt mychael

the arkaungel wryttyn in letters off gold as here folowyth whych the

fynde for envy bare hyt away ther as yt was in a table by ff[ore]

oure bl[e]ssyd lady at tewkysbery the vjth yere off the rengne

of kyng henry the vjth.[42]

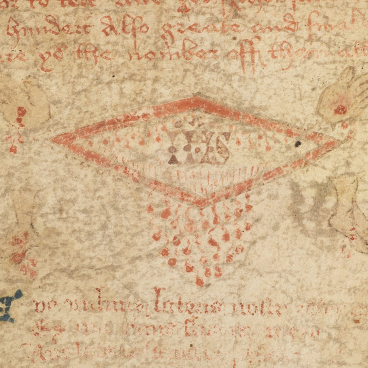

Both rolls also contain a diamond-shaped image of the side wound of Christ, with his wounded hands and feet at each corner and the monogram ‘IHS’ in the centre (fig. 9.18). In Takamiya MS 56 the first lines of the prayer ‘Aue uulnus lateris nostri redemptoris’ [Hail wound in our redeemer’s side] are written around the image of the wound; in Wellcome MS 632 this prayer appears directly below the wound (fig. 9.19). Directly above the wound in Wellcome MS 632 there is a short text on the number of drops of blood shed by Christ, which in Takamiya MS 56 appears directly after the wound image. Finally, both manuscripts include prayers beginning ‘Tibi laus vera misericordia’ [Praise to you, true mercy] and ‘Tibi laus tibi gloria’ [Praise to you; glory to you].[43] Although some of these prayers are common in other contexts, this number of shared texts may suggest some relationship between the two manuscripts.

Yet the two are also strikingly different. The recto of Wellcome MS 632 contains numerous amuletic texts and images. It opens with an image of the three nails with which Christ was crucified (fig. 9.20). Although this image carries no specific promises here, it is associated in other manuscripts with numerous protections from physical harm.[44] Given Wellcome MS 632’s habit of recording amuletic benefits in red, then prayers in black, followed by the amuletic image itself, the fact that the end of a rubric is visible where the head of the roll has been lost may indicate that promises of protection appeared here too. After the nails come the many practical benefits of the measured cross and their associated image, then a very worn text in red ink which appears to be a version of the heavenly letter. It begins ‘This ys the trewe copy of the letter the whyche a[n a]ungell [brou]ght frome hevyn to kyng [Cha]rles in the tyme […] to the batell of ronncevalle’ and promises protection to anyone who carries it upon them. Further down the roll, after several illegible texts, is the prayer to the Virgin Mary with the Tewkesbury rubric claiming that whoever uses it will have thousands of years of pardon and will see the Virgin. These texts are comparable with those in the other manuscript rolls: texts and images that promise protection and material or spiritual benefit in a range of situations.

The prayers on the recto of Takamiya MS 56, by contrast, make no promises of physical protection. This manuscript does not include the measured cross or the amuletic texts associated with it. For praying while looking at the image of the nails with contrition and devotion, it promises that the reader ‘shall haue grete grace of allmyghty god and for to putt a waye from hym all dedely synnys’ (fig. 9.21). This is significantly different from the promises attached to the nails in other manuscripts: in Henry VIII’s prayer roll and in Glazier MS 39, for example, the nails are said to provide protection against dangers including sudden death, death by sword, poison, enemies, poverty, fevers, and evil spirits (fig. 9.22).[45] Other prayers in Takamiya MS 56 guarantee thousands of years of pardon and indulgence, and the sight of the Virgin Mary. One rubric says that one of the roll’s prayers will increase the virtue of another tenfold. Unlike the prayers in the other manuscripts identified as ‘birth girdles’, all of these benefits are spiritual, not physical. Furthermore, the contrast between the promises attached to the image of the nails here and elsewhere suggests that the omission of physical benefits was deliberate.

Both Wellcome MS 632 and Takamiya MS 56 can justifiably be described as birth girdles based on the text on their dorse. Their physical format, the positioning of their texts, and their user’s interactions with them all combine to assimilate them into the girdle relic itself. However, their recto texts suggest that when not being used in childbirth they functioned in quite different ways. Despite the similarity between their texts and their mutual birth girdle function, one of these manuscripts was designed to be used for spiritual benefit, while the other could be used largely for physical protection.

I have argued above that the term ‘birth girdle’ has been misapplied to many rolls, obscuring their alternative possible uses as devotional objects or amulets for general protection. Since no evidence remains to suggest that the majority of these rolls were used for girdling women during childbirth, we must reconsider them in the light of other devotional and amuletic rolls: any explanation for the use of the roll format must take into account the existence of rolls containing exclusively non-amuletic prayers.[46] Furthermore, the differences between Takamiya MS 56 and Wellcome MS 632, despite their many shared texts, indicate that even persuasive ‘birth girdles’ could be used in divergent ways. Even where the ‘birth girdle’ designation is correct, therefore, it is not complete: in order to understand how rolls were used, we must remain sensitive to their full diversity.

Appendix: Known English ‘Birth Girdles’

London, British Library, Additional MS 88929

London, British Library, Harley 5919, items 143 and 144 (STC 14547.5)

London, British Library, Harley Charter 43.A.14

London, British Library, Harley Roll T.11

London, Wellcome Library, Wellcome MS 632

New Haven, CT, Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Beinecke MS 410

New Haven, CT, Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Takamiya MS 56

New York, NY, Pierpont Morgan Library, MS Glazier 39

Philadelphia, PA, Redemptorist Archives of the Baltimore Province (no call number)

Research for this paper was funded, in part, by a Short-Term Fellowship from the Bibliographical Society of America and by a Hope Emily Allen Dissertation Grant from the Medieval Academy of America.

Katherine Storm Hindley is Assistant Professor in Medieval English Literature at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. She holds first degrees from Oxford and a PhD from Yale. Her research interests lie at the intersection of medieval literature, manuscript studies, and the history of medicine, focusing on the belief that spoken and written words had the power to heal and protect. She is currently completing a monograph on this topic. Her research has been supported by the Medieval Academy of America, the Bibliographical Society of America, and the De Karman Foundation, among others.

Citations

[1] Nicholas Harris Nicolas (ed.), Privy Purse Expenses of Elizabeth of York: Wardrobe Accounts of Edward the Fourth, with a Memoir of Elizabeth of York, and Notes (London: William Pickering, 1830), p. 78.

[2] William Douglas Hamilton (ed.), A Chronicle of England During the Reigns of the Tudors, from A.D. 1485 to 1559 (Westminster: J. B. Nichols and Sons, for the Camden Society, 1875), p. 31. In Yorkshire alone, the 1535 visitation of Layton and Legh found sixteen belts or girdles specifically used for protection in childbirth, as well as eleven others whose purpose is not specified. The girdles for protection of pregnant women are those of St Francis at Grace Dieu, St Bernard at Melsa and Kirkstall, St Ailred at Rievaulx, St Werburgh at Chester, St Robert at Newminster, St Saviour at Newburgh, Thomas of Lancaster at Pontefract, St Margaret at Tynemouth, the former prior of Holy Trinity in York, Mary Nevill at Coverham, and of the Virgin at Haltemprise, Calder, Conished, Kirkham, and Jarvaux. See Thomas Legh and Richard Layton, ‘Compendium Compertorum Per Doctorem Legh Et Doctorem Leyton in Visitatione Regia Provinciæ Eboracensis’, in Samuel Pegge (ed.), Annales Eliæ De Trickingham Monachi Ordinis Benedictini (London: ex officina Nicholsiana, 1789).

[3] These are: the British Library’s Additional MS 88929, Harley Roll T.11, and Harley Charter 43.A.14; the Wellcome Library’s MS 632; MS Glazier 39 at the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York; Beinecke MS 410 and Takamiya MS 56 at the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library in New Haven; and a manuscript formerly known as the Esopus Roll in the possession of the Redemptorist Archives of the Baltimore Province, Philadelphia. The printed sheet (STC 14547.5) is now cut into two pieces, and is held by the British Library as items 143 and 144 in Harley 5919, a scrapbook of English printing samples collected by the antiquarian John Bagford. See, for example, Peter Murray Jones and Lea T. Olsan, ‘Performative Rituals for Conception and Childbirth in England, 900–1500’, Bulletin of the History of Medicine 89:3 (2015): p. 426, n.55; Joseph J. Gwara and Mary Morse, ‘A Birth Girdle Printed by Wynkyn De Worde’, The Library 13:1 (2012): 33–62; Mary Morse, ‘Alongside St Margaret: The Childbirth Cult of SS Quiricus and Julitta in Late Medieval English Manuscripts’, in Emma Cayley and Susan Powell (eds), Manuscripts and Printed Books in Europe 1350–1500: Packaging, Presentation and Consumption (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2013), 187–206. The other rolls mentioned by Jones and Olsan do not appear to be English.

[4] London, British Library, Sloane MS 431, fol. 52r.

[5] Gwara and Morse, ‘Birth Girdle’, p. 39. The texts are absent from Takamiya MS 56, although it should be noted that at least one membrane is missing from the head of the manuscript. Takamiya MS 56 does include an image of the cross surrounded by the instruments of the Passion, but does not mention its measurements or attach any specific amuletic properties to it.

[6] Jacobus de Voragine, ‘Legenda Aurea’, in Giovanni Paolo Maggioni (ed.), Legenda Aurea (Florence: Edizioni del Galluzzo, 1998), pp. 532–533.

[7] Morse, ‘St Margaret’, p. 188.

[8] Gwara and Morse, ‘Birth Girdle’, pp. 36–37.

[9] Gwara and Morse, ‘Birth Girdle’, pp. 36–37.

[10] The cross is usually depicted as an empty tau cross, sometimes with the instruments of the Passion, although in British Library Additional MS 88929 Christ hangs on the cross. In the roll held by the Redemptorist Archives of the Baltimore Province, the cross is replaced with a vertical blue ‘lyne’ with red zig-zag decoration. The focus on measurement, which is evident in several of the amuletic images in these rolls, was common in the late medieval period. The phenomenon is discussed in, for example, Michael Bury, ‘The Measure of the Virgin’s Foot’, in Debra Higgs Strickland (ed.), Images of Medieval Sanctity: Essays in Honour of Gary Dickson (Leiden and Boston, MA: Brill, 2007), pp. 121–134.

[11] The English text in Harley 43.A.14 is quite different to those in the other rolls. It is edited, along with the measured cross text from Glazier MS 39, in Curt F. Bühler, ‘Prayers and Charms in Certain Middle English Scrolls’, Speculum 39:2 (1964): pp. 274–275.

[12] I have replaced manuscript þ with th throughout.

[13] New Haven, Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Beinecke MS 410. ‘Saynt John latynes’ refers to the basilica of St John Lateran in Rome.

[14] The Latin prayers to Quiricus and Julitta in the printed sheets are unrelated to those in the manuscript rolls and make no reference to the measured cross or to childbirth. The roll held by the Redemptorist Archives of the Baltimore Province contains a prayer that is closely related to the version in the other manuscript rolls, but it appears to have been damaged and over-written at the relevant point. The standard prayer reads, in part, ‘tribue michi Thome famulo tuo humilitatem et virtutem gloriose longitudinis tue ac venerabilis crucis tue’: ‘grant me, your servant Thomas, humility and the virtue of your glorious measure and your venerable cross’.

[15] In codices, the Latin prayer does occasionally occur without the image of the cross. See, for example, London, British Library, Additional MS 37787, fol. 92r.

[16] The printed broadsheet STC 14077c.64, held at Harvard’s Houghton Library, associates Quiricus and Julitta with a wide range of protections including safety in childbirth, but not with the measured cross. See Gwara and Morse, ‘Birth Girdle’, pp. 61–62 and fig. 4. London, British Library, Sloane MS 783 B, fol. 215r, invokes the saints for protection against various dangers, with no mention of childbirth. An English prayer to the saints with no mention of childbirth appears on fol. 2v of Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum, MS 48. See Morse, ‘St Margaret’, p. 195.

[17] London, British Library, Egerton MS 2781. Kathryn A. Smith, Art, Identity and Devotion in Fourteenth-Century England: Three Women and Their Books of Hours (London, Toronto and Buffalo: The British Library and University of Toronto Press, 2003), pp. 32, 36, and 315.

[18] Smith, Art, Identity and Devotion, p. 316. The rubric reads: ‘Ceste oresoun apres ceste ruberike uous que estes gros denfaunt a matyn. quant uus le uotre leyt [culez].’

[19] New Haven, Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Beinecke MS 410; New York, Pierpont Morgan Library, MS Glazier 39; London, British Library, Additional MS 88929; London, British Library, Harley Ch. 43.A.14; and the printed sheet preserved as items 143 and 144 in the British Library’s Harley 5919.

[20] Oxford, Bodleian Library, Bodley MS 177, fol. 61v, edited in C. T. Onions, ‘A Devotion to the Cross Written in the South-West of England’, The Modern Language Review 13:2 (1918): p. 229.

[21] The charm as it appears in Harley Roll T.11 is edited in W. Sparrow-Simpson, ‘On a Magical Roll Preserved in the British Library’, Journal of the British Archaeological Association 48 (1892): p. 51. For more on the peperit charm, see Marianne Elsakkers, ‘“In Pain Shall You Bear Children” (Gen. 3:16): Medieval Prayers for a Safe Delivery’, in Anne-Marie Korte (ed.) Women and Miracle Stories: A Multidisciplinary Exploration (Leiden: Brill, 2001), 179–207. The earliest surviving examples of the Sator-Arepo formula in an English manuscript is written in the margin of Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 41, p. 329.

[22] The image of the side wound has often been described as a childbirth image: see, for example, Caroline Walker Bynum, Christian Materiality: An Essay on Religion in Late Medieval Europe (New York, NY: Zone Books, 2011), p. 202. However, I believe that this description limits the perceived function of the image, much as the description of rolls as ‘birth girdles’ limits their interpretation. As well as promising safety in childbirth, the side wound in Harley T.11 protects its owner against death by sword, spear, and shot; being overcome in battle; and from both fire and water.

[23] For more on the side wound image and on measurement in medieval devotion see, for example, David S. Areford, ‘Printing the Side Wound of Christ’, Ch. 5 in The Viewer and the Printed Image in Late Medieval Europe (Farnham: Ashgate, 2010), pp. 228–267.

[24] Ann Eljenholm Nichols, ‘O Vernicle: A Critical Edition’, in Lisa H. Cooper and Andrea Denny-Brown (eds.), The Arma Christi in Medieval and Early Modern Material Culture: With a Critical Edition of ‘O Vernicle’ (Farnham and Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2014).

[25] These six manuscripts are Cambridge, MA, Harvard University, Houghton Library, MS TYP 193; London, British Library, Royal MS 17 A xxvii; London, British Library, Additional MS 32006; Aberdeen, Sir Duncan Rice Library, Scottish Catholic Archives CB/57/9 (formerly in Edinburgh); San Marino, CA, Huntington Library, MS HM 142; and Marquess of Bath, Longleat MS 30. See Linne R. Mooney et al., The Digital Index of Middle English Verse, no. 5196.

[26] Philadelphia, Redemptorist Archives of the Baltimore Province.

[27] In the Latin prayer to Quiricus and Julitta on the dorse of the roll, the text reads ‘[mi]chi famule tue .N.’: ‘to me, your [female] servant, [name]’.

[28] London, British Library, Harley Ch. 43.A.14: ‘tribue michi Willelmo famulo tuo’: ‘grant me, William, your servant’.

[29] New Haven, Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Beinecke MS 410: ‘tribue mihi . Thome famulo tuo’: ‘grant me, Thomas, your servant’. This may be Thomas Barnak of Lincolnshire: see Barbara Shailor, Catalogue of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts in the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, vol. 2 (Binghamton, NY: Medieval & Renaissance Texts & Studies, 1987), pp. 308–311.

[30] London, British Library, Additional MS 88929. The inscription, probably in Henry’s own hand, reads ‘Wylliam thomas I pray yow pray for me your lovyng master Prynce Henry’. The original owner or donor of the roll may have been the unidentified bishop depicted kneeling before the Trinity. Scott McKendrick, John Lowden, and Kathleen Doyle, Royal Manuscripts: The Genius of Illumination (London: The British Library, 2011), p. 186.

[31] New York, Pierpont Morgan Library, MS Glazier 39. In a colophon at the end of the roll the scribe writes: ‘Chanoun in Couerham with owten le | In /[th]e\ ordere of Premonstre | [Th]at time [th]is schrowyll I dyd wryte […] In Rudby towne of my moder fre | I was borne wyth owtyn le | Schawyn I was to [th]e order clene | the vigill of all haloes evyn | My name it was percevall | Ihesu to [th]e blys he bryng vs all.’ See John Block Friedman, Northern English Books, Owners, and Makers in the Late Middle Ages (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1995), p. 169.

[32] Don C. Skemer, Binding Words: Textual Amulets in the Middle Ages, Magic in History (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University, 2006), p. 263.

[33] Morse, ‘St Margaret’, p. 202.

[34] London, British Library, Harley Roll T.11 also uses these masculine forms in prayers including the one to Quiricus and Julitta.

[35] Gwara and Morse, ‘Birth Girdle’, p. 37.

[36] Mary Morse, ‘Two Unpublished Elevation Prayers in Takamiya MS56’, Journal of the Early Book Society 16,(2013): p. 269.

[37] Mary Agnes Edsall, ‘Arma Christi Rolls or Textual Amulets? The Narrow Roll Format Manuscripts of “O Vernicle”’, Magic, Ritual & Witchcraft 9 (2014): pp. 206–209. London, British Library, Harley Ch. 43.A.14, is 7 cm wide but just 46 cm long: too short to realistically serve as a girdle. British Library, Harley Roll T.11 measures 8.5 x 121 cm, while British Library, Additional MS 89929 measures 9.7 x 134.6 cm.

[38] Daniel James Waller, ‘Echo and the Historiola: Theorizing Narrative Incantation’, Archiv für Religionsgeschichte 16:1 (2015): pp. 263–280.

[39] Edina Bozóky, ‘Mythic Mediation in Healing Incantations’, in Bert Hall, Sheila Campbell, and David Klausner (eds), Health, Disease and Healing in Medieval Culture (New York: St Martin’s Press, 1991), pp. 86–87.

[40] One example of this charm, from British Library, Additional MS 33996, fol. 149r, is edited in Tony Hunt, Popular Medicine in Thirteenth-Century England: Introduction and Texts (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 1990), p. 29.

[41] Matthew 9:20–2; Mark 5.25–34; Luke 8.43–8.

[42] I am very grateful to Ian Green for the digital processing of manuscript images that made this text, and others in this roll, legible.

[43] A prayer beginning ‘Tibi laus tibi gloria’ also appears in MS Glazier 39 but does not otherwise match the texts in these two rolls.

[44] See, for example, MS Glazier 39 and British Library Additional MS 88929.

[45] London, British Library, Additional MS 88929; New York, Pierpont Morgan Library, MS Glazier 39

[46] For example, New York, Columbia University, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Plimpton Add. MS 4 contains the ‘Fifteen O’s’ in English verse.

DOI: 10.33999/2019.11