In 1971, after having completed a series of works on paper that used the words of French dramaturg and playwright Antonin Artaud as their subject, American feminist artist Nancy Spero began work on her thirty-seven-panel piece, Codex Artaud. Moving away from the relatively modest dimensions of her earlier Artaud Paintings (1969–70), Spero began pasting sheets of Japanese Sekishu paper together to form long, thin collages that she described as ‘scroll works’.[1]Codex Artaud (1971–2) established the wrought aesthetic and abstract world that dominates her scrolls throughout the 1970s. Affixed are small, drawn images of distorted bodies, disembodied heads, and extracts of Artaud’s tortured prose, cut out and collaged on. The extended paper support is largely white and crumpled, punctuated with sheets of coloured and tracing paper that contain typewritten extracts of Artaud’s texts. As this chapter will expound, this strange and anxious scroll stands as an early representation of Spero’s emerging feminism; developed as part of her increased involvement in feminist art world activism and an attention to the political potentials of artworks. Thinking about why the scroll and its historical resonances seemed politically potent to the artist in the 1970s, I will examine how, for Spero, the scroll format was essential in creating a feminist mode of viewing, becoming in this work, an activist and anti-patriarchal form.[2]

The period during which the scroll emerged in Spero’s oeuvre was one where the artist— as one of the early members of the feminist art movement—was dedicating herself to activism. Interrogating the conditions of women’s experience under patriarchy, the women’s movement in the arts developed existing aesthetic strategies in order to mount a critique of a system that oppressed women as part of its functioning. The focus of these works ranged from an examination of the mechanics of oppression, such as in Mierle Laderman Ukeles’ Maintenance Art in which she proposed to exhibit maintenance activities associated with work in the home as her artistic practice, to an attention on the constructed nature of gender, for example as demonstrated in Eleanor Antin’s Representational Painting (1971), a film that shows Antin layering her face with make-up over the course of its nearly forty minutes. Similarly to these and other practitioners, feminist activism accompanied aesthetic response for Spero. Involved in the establishment of feminist groups emerging from the anti-war and artists’ rights activism of the Art Workers Coalition—Women Artists in Revolution in New York in 1969, joining the Ad Hoc Women Artists’ Committee in 1970, and co-founding the A.I.R. Gallery in 1972—Spero worked with others to actively challenge the blind spots of the art world, to fight for equal representation of women in the arts and to agitate for the end to the maintenance of misogyny through culture.[3]

In her practice, she investigated new material forms that would stand as alternatives to what she saw as the patriarchal art object, summing up this move with the pithy phrase: ‘There, you guys can splat on your big canvases, but I’m over here doing this fragile thing – with bite’.[4]

She had first changed her aesthetic approach to suit political making as part of her involvement in activism against the Vietnam War in the mid-1960s. Abandoning the technique that dominated her paintings of the 1950s and early 1960s, such as Lovers (1962), in which thick layers of oil on canvas were built up over months, she created works on paper with brightly coloured gouache and ink, conceiving them as ‘manifestos’ against US governmental aggression in her War Series (1966-70). Nearing 150 works in total, the War Series represented outrage through its sexual, scatological, and aggressive iconography, enhanced by the speed of their making, which left an indexical record of quick brushstrokes and violent rubbing on the paper’s surface. Spero’s turn to the scroll in the early 1970s stemmed from her recent ideological engagement with feminism, standing as a mode of making that could encourage feminist viewing, rejecting the machismo and bombast epitomised for the artist in the then ageing abstract expressionist canvas, and instead create an active, reciprocal engagement between viewer and artwork.

The Codex Artaud is interesting for the ways in which the emerging scroll form manifests both Spero’s feminist ambition and the anger of the War Series. Her later works—a key example of which is Notes in Time on Women (1976–9)—make women the protagonist, considering a plurality of female identities and experiences.[5] In the Codex Artaud, the visceral outrage and aggression of the War Series drives the work, simmering in the iconographic and textual elements and creating a visual rendering of the effects of patriarchy on women. Fragmented bodies, decapitated heads, and extended tongues are pictured alongside phantasmal beasts, insect-like creatures, and ripped, stuttering transcriptions of Artaud’s texts. The subject is treated violently, both in representation and in the manipulation of Artaud’s writing. Spero had chosen Artaud because of the extreme nature of his pronouncements, ‘forcing a “collaboration”’ on him in order to use his vast and complex texts on alienation to represent her own experience, selecting quotations that contributed to her message.[6] Using a visual and textual language of antagonistic disaffection, Spero builds a picture of a turbulent world that evokes the psychic experience of isolation and exclusion. The disorder that the work images is complemented by the elongated paper panel, the effect of its texture and white space acting to amplify its terse political proposition. Codex Artaud was Spero’s first sustained exploration of the scroll; its feminism was articulated through exploring alienation in relation to questions of gender, with Artaud’s hysterical voice and a focus on the body creating a complex consideration of the feminine.[7] In the long paper supports of the Codex Artaud, an anguished and fragmented thesis is built that obliquely explores the suffering of women living under patriarchy. The scroll form facilitates this feminist message, most notably in its complex reference to historical practice, but also in its use of paper as a devalued material, and the way in which the viewer’s experience is influenced by the scale of the work.

From its first appearance in her oeuvre, the scroll stood for Spero as a synecdoche of the ancient. As other chapters in this publication show, the form itself is not by nature historical, with many examples in contemporary art that look to the processes of modernisation and mechanisation in their rolled supports.[8] For Spero, however, the scroll signified a pre-modern mode of aesthetic production. ‘History’ held a dual significance for the work. Primarily, allusion to historical practice stood in confrontation with formalism, particularly a Greenbergian progressive modernism, and its associated machismo. Speaking to Marjorie Welish in 1994, Spero describes her antipathy towards progress: ‘You know I don’t believe in progress in art. Prehistoric art can’t be beat! Sophistication isn’t progress’.[9] Referring to historical forms provided an alternative formal language that was at once innovative, introducing new modes of making in order to develop alternative political and artistic practices, and also referred to something with weight and authority: a longstanding, respected, and to some extent mysterious tradition with which her work could connect. Scaffolding this is the implication of a lost matriarchy, an alternative historical tradition that has been aggressively erased. It is the enigmatic quality of an allusion to history that creates the second level of significance for the Codex. As Benjamin Buchloh has written, the Codex and its repeated reference to historical forms speaks to ‘painting’s lost resources in myth’ and, by extension, ‘myth and its “natural” association with the forces of the unconscious’.[10] The sense of deep historical time, created by both an iconography inspired by ancient artefacts and in the formal turn to the scroll, develops the turbulence figured in the object by referring obliquely to a psychic space. The use of the scroll form acts as a visual shorthand for both a partially recovered history and a desublimated psychological experience.

Spero’s interest in imaging a lost past can be read in relation to contemporaneous feminist interpretations of history, which sought to expose how history was written to exclude women and establish a narrative of male exceptionalism.[11] For feminism in the 1970s, the official recording of history through art had become associated with patriarchy, creating narratives of male achievements and losses, geniuses and leaders.[12] A number of feminist practitioners acted to correct this bias. Works by artists such as Mary Beth Edelson, Judy Chicago, and Betsy Damon, focused on fictional ancient alternatives, representing lost goddesses and matriarchies recovered through their historical allusions.[13] In Damon’s 7000 Year Old Woman (1977), for example, the artist performed dressed in white with her skin and hair painted to match, her lips black to stylise her appearance. Attached to her were four hundred bags of coloured flour, referring to the breasts of the Greek Ephesian Artemis. Performing in the street, Damon slowly walked around, cutting off the bags of flour in order to enact a pseudo-ritual.[14] Whilst this work alluded to mythology and history, it did not refer to any specific historical practice. Instead, the evocation of the ancient suggested a suppressed order, one which was intimately connected with the female and fertility. Spero’s treatment of history echoes this gesture. The sense of the ancient and its framing in relation to feminist concerns proposes another order to be recovered, one which has been suppressed because of its connection to female experience. Where Damon enacts a ritual of fertility and celebration, Spero’s Codex manifests the nightmarish underworld of patriarchy, representing the chaos and disorder that mark her experience of it. The sense that something is being uncovered is important to Spero; the dominant modes of post-war abstraction were to her mind, ‘a cover-up for what was really going on’.[15] By standing in as a formal allusion to the historical, the scroll lays the ground for this recovered history.

Spero’s iconographic and formal reference to history was based on a keen interest in ancient cultural production. Inspired by her visits as a student in Chicago to the ancient artefacts in the Field Museum’s collections, Spero had long been invested in an aesthetic language that referred to ancient cultures.[16] The range of sources that she drew on was wide, encompassing Etruscan, Egyptian, Babylonian, and medieval European practices. Explicit references are made in titles of works or in texts that accompany them to specific historical objects, such as canopic jars, figures—such as the Egyptian Goddess Nut or the medieval nun Ende—or narratives, such as the story of Helen of Troy or the Mesopotamian Goddess Tiamat. In the Codex Artaud there is a repeated reference to ancient Egyptian culture, particularly The Book of the Dead, which served as an inspiration for the work.[17] However, in spite of this citation of ancient objects and forms, Spero interpreted rather than imitated works according to her own interests, describing her collaged images in the Codex Artaud as ‘symbols ransacked from various cultures’.[18] Ransack is accurate: Spero approximated symbols for their rough implications, suggesting something emerging from underneath the weight of scholarly readings, historical interpretation, and masculinist accounts of the past. Appropriating the visual and formal language of these different sources, Spero deliberately affected an aged-aesthetic for the Codex Artaud in order to invoke history-in-inverted-commas, conjuring an approximate and sometimes inaccurate idea of the ancient signalled through the scroll form.[19] Her scrolls are not copies of objects that have gone before—as she explains, ‘when a work is completed I realize some of its sources’—nor are the symbols she uses appropriated for their original meanings.[20] Instead, they are taken on the basis of their aesthetic and conceptual associations, re-imagined by the artist as part of a feminist attack on history.

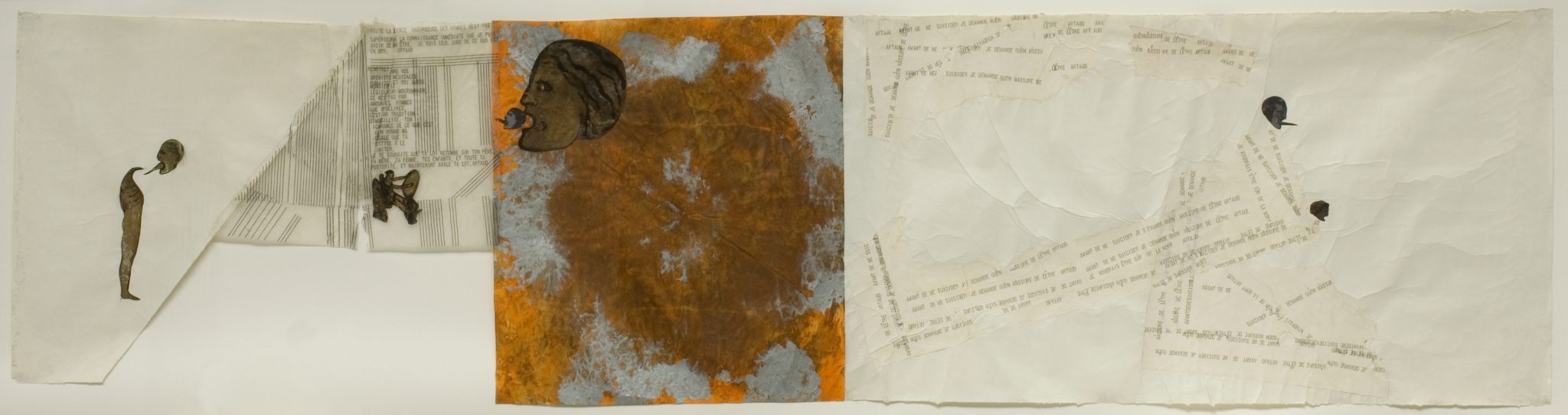

This approximation of historical modes of making, both iconographic and formal, is illustrated by Codex Artaud V (fig. 1.1). A scene at the centre of the panel in which three silver-grey figures stand, epitomises the way in which history is conjured by the artist. The clearest allusions to a historical exemplar appear in a large, totemic figure to the left of the group and a smaller, composite character on the right. The large figure stares out at the viewer with arms crossed, cutting its body in half. Dominating the panel, it exceeds the boundaries of the support, and unlike the other characters, confronts the viewer directly. With this totemic pose the figure evokes Egyptian iconography; the collar that stretches up either side of its head resembles the pharaonic headdresses like the Khat or Afnet which, combined with its two-dimensional frontality, recalls the tomb statues held in collection in the Field Museum or the coffins in which the museum’s mummies are encased. The composite figure, who is pictured with head and legs in profile and torso in full view, faces off the picture plane to the right, its arms raised so as to echo an Egyptian gesture of adoration. The third and central figure, which also stands face-on with arms crossed, is shown looking down at the worshipper. The introduction of roughly sketched perspective in the depiction of this figure’s face, departs from the tentative reference to the specific historical language of ancient Egypt.

Although there are clues as to what this scene might represent, its meaning is obscured. We could, for example, read the largest figure as a God, drawing on Egyptian stylistic tradition to consider its scale as evidence for this conclusion. However, asserting this narrative requires that we ignore other iconographic clues: the fact that the other characters face away from the larger one; Artaud’s text, which captions the vignette, describing his choice of darkness and pain over radiance; and the effect of collage, which emphasises the distance between elements attached to the resonant paper support. Although the figures suggest a narrative that is being imparted, their arrangement and their evocative expressions creating the impression of a story that waits to be deciphered, it is as though the code to read them is lost and the viewer is left to make connections from a sense of significance, trying to interpret the deliberately obscure. The artist’s description of her works as ‘hieroglyphs’, in which ‘figures themselves stand for language, just as in the symbols from ancient calligraphy or Egyptian art’ is suggestive in this regard.[21] Spero treats symbols as though they were linguistic, and meaningful in that sense, however the viewer is deliberately left without tools for translation; an implication of meaning and loose association is all we can rely on in order to understand the message.

Throughout the work, Spero appropriates historical forms as approximated signs more for a sense of meaning than for their accurate reference to historical practice. Titling the work Codex is a good example of this. As suggested by the critic Lawrence Alloway, the naming of the scroll work as a codex—which more correctly describes a bound collection of papers, not a scroll—alludes to historical forms, rather than accurately representing Spero’s objects. Certain precedents cited by the artist for her use of the scroll, such as the Bayeux Tapestry and the Beatus Apocalypse of Gerona, the dimensions and stylised figures of which provide inspiration for Spero’s aesthetic, further demonstrate an approximation of the qualities of objects.[22] Neither the tapestry nor the Apocalypses are themselves scrolls—just like the anachronistic ‘Codex’ Artaud—but instead they are invoked as palpably historical, pointing to aspects of the scroll that appeal to Spero’s engagement with it: the unfurling pictorial narrative and heavily illustrated manuscript. As her work is permanently unrolled and pinned to the wall, the dynamic of revealing and concealing associated with historical rolls and scrolls that derives from the viewer’s tactile manipulation of them is hindered.[23] Not appropriating the living engagement with the scroll, therefore, the panels of the Codex are instead more like found objects, presented on museum walls. Creating works that appear historical, that imply a lost practice to be deciphered, Spero’s interest in adopting the form is more about the way in which it suggests itself as an artefact; something that is kept distant, its use and significance not entirely recoverable.

Also contributing to Spero’s opposition to modernist tradition is the use of paper as a material, which asserts the artwork as an ephemeral and fragile artefact. Taking on the artistic and critical claims for what Lucy Lippard terms the ‘dematerializ[ed] art object’ and developing them through her own focus on women’s practice, Spero saw paper as a disposable and devalued material, one which rejected the veneration of art works and instead encouraged quick, free, and feminist making.[24] Casting aside the oil and canvas of her early practice, which according to this new understanding of materials associated it with a masculinist history of painting, Spero turned to paper. She explains: ‘I started to think: I don’t want my stuff to be so permanent, so important’.[25] The sexualised, grotesque, and phantasmal picturings of the horrors of the Vietnam War in the War Series were facilitated by paper’s fragility and impermanence, representing both the violence of the conflict and the vulnerability of the human body. Spero attacked the support, washing it with gouache in colours abject and bodily, spitting on her brushes and scrubbing at the paper’s surface, so much at times that it ripped and tore during the construction. In the Codex Artaud, Spero similarly used the delicate nature of her materials to contribute to meaning through its tactile and textural presence. The delicacy and friability of the paper supports became an important layer of signification; the rips, tears, and buckles in the ground of the image contribute to the turbulence represented in the images of fragmented figures and the anxious fragments of text.

Codex Artaud I stands as an example (fig. 1.2). The materiality of the four paper panels pasted together greatly contributes to its meaning. At some points thick, crumpled, and marked, at others so thin as to be nearly entirely transparent, the paper creates a resonant and connotative ground. Artaud’s appropriated words are typed on separate sheets of paper glued to the surface, so as to pucker the scroll and pull the paper into vein-like lines that run across the support. Multiple transcriptions of Artaud’s anguished plea—which translates to ‘before committing suicide I ask that I be given some assurance of being’—are affixed to a section of paper marked with deep creases that form a web across the picture plane, subtly extending the pain of the words into the material itself. Creases act as echoes of trauma, allegorising the suffering described by Artaud, and creating an unstable basis for this anxious world. Spero’s affective meaning-making is developed in the layered scraps of paper containing Artaud’s words that are pasted on top of one another. At points, they meld into a single piece that erases and destroys the legibility of the words, echoing the text’s anxiety about being and annihilation. Semi-circular rips in these extracts are made more visible through contact with the paper beneath; their thin, yellowing edges mark them out against the handmade paper of the support. Spero plays with texture in ways that accentuate the delicacy of her medium, emphasising the volatile and precarious world that is built of deformed bodies and anguished texts. Fragility here seems to act as a metaphor for psychic turbulence. The disintegration of material elements forms an important part of the work: the edges of the tracing paper that carries a longer section of Artaud’s text are ripped unevenly; in the centre of the bottom of the fragment a tear runs through the piece, splitting the surface. Further up, the text is obscured by a hard crease that extends through the centre of this section, meaning that, although we can discern the words that are typed, they are truncated, partially erased, and interrupted by the frailty of the medium.

The rough edges of the paper panels, where the fibrous quality of the support are made visible, add to the sense of a disorderly and turbulent world. As paper, each page consists of multiple individual fibres compressed so as to form a whole, creating a chaotic material composition. Unlike canvas, in which the material is constructed from ordered lines of cotton or linen, paper is made up of uneven fibres that are shaken to become entwined.[26] Therefore, there is a discontinuity even on a material level that allows constitutive elements to be divided across different sheets; not an ordered makeup, but instead an anarchic spread which creates a material that is at once connected to and separated from itself. The space of the paper is one that suggests a space bracketed off, there to be looked at as much as the collaged elements, an equal constituent in the process of making meaning. In their construction from paper, the scrolls assert a physical and affective presence that rejects the ‘valuable’ artwork, and by extension the system that values it. Paper, with its fragility that records trauma to its surface, is an essential contributor to this attack on the masculine art object, rejecting the ordered smooth facade of oil on canvas and instead presenting a traumatised object in which harm is integral to its aesthetic.

A final but important part of this attack by Spero’s scrolls on masculine modes of production was an attempt to rethink the relationship between artwork and viewer. Spero sought to end the contemplative role of the spectator, rejecting a mode wherein they would stand and receive the artist’s message, instead using the elongated ground of the image to force the viewer to engage with the work as an active participant. Although tactile manipulation is refused by their display on the wall, looking at Spero’s scrolls, like any scroll, requires a physical relationship with the object; these demand that the viewer move and respond to the contrast between small elements pasted onto the support and the scale of the whole. In inviting an active and bodily form of viewing, the artist played with the dimensions of her fragments in relation to the size of the support, using small and delicate extracts of typed texts as a means to draw the viewer into an intimate relationship with the work, while large images and an extensive span lead them to seek distance. Moving along the totality of the work, seeking detail in small sections and coherence in the whole, the scrolls engage the body of the viewer, creating meaning through action. This relational practice creates a unique engagement for each viewer, allowing for a more reciprocal relationship—understood by the artist to be feminist—to develop between object and audience.

This mode of viewing is visible in Codex Artaud V and Codex Artaud I: the viewer is required to stand back to take in their span, but must also come close to the panel in order to see the detail of their small collaged heads and to read texts that are almost indiscernible from a distance. However, the effect is best illustrated in Spero’s later works, ones in which panels are less autonomous, and instead multiple scrolls are grouped together to explore particular themes. The 1986 work Marduk (fig. 1.3) provides a good example. Describing the ancient Mesopotamian creation myth of Marduk and Tiamat, the three dark blue paper panels are printed with white ink and have attached to them accounts regarding the contemporaneous oppression of women across the world. These accounts are transcribed in English, including headings from newspaper extracts and human rights reports such as ‘REAGAN’S SILENCE ON ABORTION TERROR’, ‘USSR HOLDS WOMAN IN MENTAL HOSPITAL’, and ‘PARAGUAY: THIRTY YEARS OF HUMAN RIGHTS ABUSE’. By 1986, Spero’s focus was on foregrounding women, in this case their mistreatment under patriarchy, with evidentiary texts affixed to the support, pointing to the continuing violence that women endured across the world. These texts are headlined by a transcription of the tale of Marduk’s violent defeat of the goddess Tiamat in order to take control of the earth and assert order over a chaotic realm. It reads:

Marduk caught Tiamat in his net, and drove the winds

which he had with him into her body, and whilst her belly

was thus distended he thrust his spear into her, and stabbed

her to the heart and cut through her bowels, and crushed her

skull with his club. On her body he took his stand, and with

his knife he split it like a flat fish into two halves, and of one

of these he made a covering for the heavens.

Creating a historical continuity between the violence inscribed in mythology and that described in the texts, this relationship is built by the discrepancies in scale that are central to Spero’s active scrolls. In order to read this tale, which spans nine meters across the three panels, the viewer needs to be at a remove to take in the whole account, moving along the paper panels in order to read it in full, then moving back to the far left of the first panel halfway through in order to take in the second row of woodblock printed text. That this is to be read in a continuous flow is made clear by the arrangement of lettering: the word heavens, for example, is split in two, with the letters ‘HE’ on the middle panel and ‘AVENS’ on the right. In order to take in the entirety of the story of the eponymous character, it is necessary not only to be distant from the panel, but also to move along it. In order to get the detail of the work—the information about the real experience of women—it is necessary to be close to it and to dedicate time and concentration to a small section. The viewer is brought into a physical and intellectual relationship with the panels; not only do they absorb a message, but they actively create meaning through their approach to the work, developing their own unique engagement through the way in which they choose to explore its elements. Tapping into the scroll’s mobility as a form, Spero considers this physical relationship—as opposed to the conventional role of the viewer of the artwork—with its expectation of stillness and contemplation. Instead, the experience is described as cinematic, the way in which a picture is built involving long-shots and close-ups, vignettes that are loaded with meaning put into context of the whole, building an understanding of the work that sees the time spent examining and engaging with the piece as part of its significance. Describing this in 1972, Spero states:

To view Codex Artaud one has to change position, to move

close or further away according to the size of the images … to

move along as in reading a manuscript, or to move further away

to view it in its entirety. My ideas on using collage technique are

related to the fleeting gesture, moments (indelible impression)

caught in motion. The rhythm of the whole, seemingly discordant,

incomplete, or inchoate relates to fractured time – as well as the

immediate external realities that impose themselves on my

consciousness.[27]

Claiming a political aspect to this type of spectatorship, seeing its active engagement as collaborative, non-hierarchical, and feminist, the scroll form enabled a change in the way in which an artwork claims authority over the viewer. In inviting a response to the object that was based on movement, allowing the spectator to create meaning with their journey through the work, the scroll was essential to the development of a feminist object. The progress of her practice evidences Spero’s investment in this mode of viewing, which moved from scroll works to interpretations of the heraldic banner in A Cycle in Time (1995), and to large-scale murals that intervened in institutional spaces in ways that exposed their ideological biases. However, her understanding of the scrolls’ promise is evident through her consistent engagement with it throughout her career, establishing itself in the early 1970s and culminating in the 2002 work Azur, which was approximately eighty-five meters in length and included a range of images of women from contemporary and ancient sources. Working with the form for over thirty years, the scroll was a major part of Spero’s aesthetic proposition.

The scroll form, in Spero’s feminist reimagining, was appropriated and dispatched as part of a challenge to the aesthetic status quo, seen by the artist as complicit in the oppression of women and the perpetuation of patriarchy. With its allusion to history, its devalued support, and its extended scale that demands an unconventional and active mode of viewing, the form was essential to Spero’s activist practice. The scroll worked both to signify and to delineate a space of signification, its traumatised paper supports both the ground for her fragmented images and texts, resonant and meaningful in their own right. Contributing to the contemporaneous feminist attention to the past that sought to use its language as a way to counter history’s ideological message, Spero’s angry artefacts mimicked the ancient in order to intervene in the contemporary moment. In this way, for Spero, her interpretation of the scroll form and her manipulation of its resonances were essential to her feminist practice, a potent and active mode of making.

Rachel Warriner is British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow at the Courtauld Institute of Art. Her research focuses on the emergence of activism among women artists in 1970s New York, considering the emergence of feminist art in the context of the art politics of the time. This project builds on her previous work on Nancy Spero which will be published in her book Pain and Politics in Postwar Feminist Art: Activism in the Work of Nancy Spero, forthcoming from I.B Tauris.

Citations

[1] Nancy Spero and Stephan Götz, ‘About Creation: Interview with Stephan Götz’, in Craigen W. Bowen and Katherine Oliver (eds), American Artists in Their New York Studios. Conversations About the Creation of Contemporary Art (Cambridge, Massachussetts; Stuttgart: Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, Harvard University Art Museums; Daco-Verlag Günter Bläse, 1992), p. 149.

[2] It should be noted that Spero is not the only feminist to adopt the scroll as part of her feminist practice. The most notable other example is Carolee Schneemann’s Interior Scroll pulled from her vagina at her performance at the Women Here and Now Festival in East Hampton in 1975 and the Telluride Film Festival in Colorado in 1977, which contained text from her book Cezanne, She was a Great Painter. Exploring vulvic space, Schneemann used the scroll to make visible the interior spaces of the body, asserting meaning and a challenge to masculine production through her performance.

[3] For more on feminist art and its histories see Helena Rickett and Peggy Phelan, Art and Feminism (London and New York: Phaidon Press, 2012).

[4] Nancy Spero, Nicole Jolicoeur and Nell Tenhaaf, ‘Defying the Death Machine’, Parachute 39 (1985): pp. 50–55; reprinted in Roel Arkesteijn (ed.), Codex Spero: Nancy Spero — Selected Writings and Interviews 1950–2008 (Amsterdam: Roma Publications, 2008), p. 15.

[5] See Nancy Spero and Jeanne Siegel, ‘Nancy Spero: Woman as Protagonist’, Arts Magazine 62 (1987): pp. 10–13.

[6] Nancy Spero and Barbara Flynn, Nancy Spero. 43 Works on Paper. Excerpts from the Writings of Antonin Artaud (Cologne: Galerie Rudolf Zwirner, 1986), p.1.

[7] Although Spero asserted that Codex Artaud was not feminist, instead claiming it as a pre-feminist practice in that it did not explicitly foreground women and their experience, it undoubtedly shows an attention to feminism’s intellectual concerns; the focus on the body as the site and signifier of existential pain suggests an interest in embodiment and a dedicated attention to emotion as a serious subject for intellectual enquiry. See Spero and Tamar Garb, ‘Nancy Spero interviewed by Tamar Garb’, Artscribe International (1987): p. 59. Mignon Nixon describes how the Codex Artaud explores a hysterical subjectivity that develops a consideration of both sexuality and gender. See Nixon, ‘Book of Tongues’, in Dissidances (Barcelona: Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona, 2008), pp. 21–53.

[8] For example, artists like Robert Rauschenberg’s Automobile Tire Print (1953) and Jean Tinguely’s Méta-matic n17 (1959) produced indexical prints on rolls of paper, parodying the process and results of mass production.

[9] Nancy Spero and Marjorie Welish, ‘Word into Image. An Interview with Marjorie Welish’, BOMB 47 (1994): pp. 42–44; reprinted in Arkesteijn, Codex Spero, p. 155.

[10] Benjamin Buchloh, ‘Spero’s Other Traditions’ in Catherine de Zegher (ed.), Inside the Visible (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1996), p. 243.

[11] Talking to Tamar Garb in 1987, she states: ‘I think of history painting as a monument to a moment or a meeting in which there is usually a male action’, Spero and Garb, ‘Interview’, p. 62.

[12] Texts such as Linda Nochlin’s foundational ‘Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists’, published in 1971 opened discussion, considering the terms by which this exclusion was perpetuated. For example, the lack of educational opportunities for women, the expectations of established gender roles, and the emphasis on the artist genius understood to be male. See Nochlin, ‘Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists’, ARTnews (1971): p. 22.

[13] Mary Beth Edelson’s 1973 photograph, Woman Rising for example, involves manipulations applied to the artist’s image in order to imply a primordial and spiritual connection to the earth, alluding to a lost matriarchy connected to nature.

[14] Jayne Wark examines Damon’s performance in more detail in her Radical Gestures: Feminism and Performance Art in North America (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s Press, 2006), pp. 63–64.

[15] Nancy Spero and Robert Enright, ‘Picturing the Autobiographical War. An Interview with Robert Enright’, Border Crossings 23, no. 1 (2004): pp. 50–61; reprinted in Arkesteijn, Codex Spero, p. 35.

[16] Spero articulates the influence of the museum’s vast collections of ancient artifacts which were, according to the artist, ‘literally dumped out of the cases’. See Nancy Spero, Kate Horsfield and Lyn Blumenthal, ‘On Art and Artists: Nancy Spero’, Profile 3:1 (1983): p. 2.

[17] Spero states: ‘When I started pasting the paper together for the “Codex” I was looking at Egyptian hieroglyphics – their methods of composition on walls and papyrus, to give me some ideas, and along the way I collected many images and references’. See Spero quoted in Jon Bird, ‘Part II, “Codex Artaud” – the phallic tongue’, in Nancy Spero (London: Institute of Contemporary Art, 1987), p. 25.

[18] ‘Statement for Magiciens de la Terre’ (1989), Box 5, Folder 11, Nancy Spero Papers 1940s–2009, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

[19] For example, in her process of making the scrolls, she describes her use of Higgin’s vegetable glue for the way it puckered and yellowed the paper, telling Stephan Götz in 1992 that: ‘I wanted the work to look old’. Spero and Götz, ‘About Creation’, p. 117.

[20] Spero, ‘Narrative Aspects of the Work’, in Arkesteijn, Codex Spero, p. 83.

[21] Spero and Welish, ‘Word into Image’, p. 155.

[22] Spero discusses the influence of the Bayeux Tapestry in her interview with Judith Olch Richards. See, Oral history interview with Nancy Spero, (February 6–July 24 2008), Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Spero’s interest in the Beatus Apocalypse of Gerona is most clearly articulated in her text ‘Ende’, which considers the work of the nun Ende who is credited with illustrating this text. See, ‘Ende’, Women’s Studies 6 (1978): pp. 3–11.

[23] Whilst originally pinned to the walls, Spero’s works are now framed behind glass, pointing to their fixed status as objects that are unrolled and designed for display.

[24] See Lucy Lippard, Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972(Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973). For Spero, paper also acted as a metaphor for the denigrated status of women artists’ work. She states: ‘If women’s work is considered less valuable monetarily, then work on paper is considered even less’. See Spero, Jolicoeur and Tenhaaf, ‘Defying the Death Machine’, p. 15.

[25] Spero, Jolicoeur and Tenhaaf, ‘Defying the Death Machine’, p. 15.

[26] ‘Production Process’, Sekishu Washi, accessed 29 July 2015.

[27] Nancy Spero ‘Viewpoint’ (November 1972), Box 5, Folder 9, Nancy Spero Papers 1940s–2009, Archives of American Art.

DOI: 10.33999/2019.02