In July 1924, Westminster was bombed daily at the British Empire Exhibition. The venue of its ruin was the Admiralty Theatre in the British Government Pavilion. This space was outfitted with the latest technology; audiences were thrilled by electrically powered miniature ships and cinematic lighting effects. The bombing of Westminster was part of a show organized by the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the War Office, a spectacle of ruin called The Defences of London. It opened with a dramatically lit nighttime scene of the Houses of Parliament and Big Ben. Suddenly, fighter planes from an unnamed enemy descended. As they dropped a sustained barrage of bombs, the familiar outlines of government buildings crumbled, leaving a smoking ruin in their place.

Once the dust had settled, the show restarted; Westminster reverted to its original form as if it had not been decimated moments before. This time, the bombers were repelled by blazing anti-aircraft guns and a squad of RAF planes that swooped in to defend the city and avert destruction. A standing air force, The Defences of London argued, was key to meeting the existential threat of modern warfare. The local setting of this dystopian fiction was an aberration in the triumphant tone of the Empire Exhibition. A perilous future in which Westminster—and the British identity that it represented—could be destroyed exhibits the resonance of apocalyptic imagery with the cultural climate of mid-1920s Britain.

The British Empire Exhibition, located in Wembley (a suburb of London), opened in April 1924. It was initially intended to last a year, but its popularity, as well as the significant government expenditure during the first year, compelled the organizers to extend it for a second season in 1925.1 The 216 acres of the exhibition site purported to encompass the power, products, and people of an empire that covered nearly a quarter of the globe.2 Dominions and colonies were spread out over a series of pavilions, while the commercial interests of the empire were represented in the Palace of Engineering and the Palace of Industry. The Empire Stadium could hold an audience of 30,000 and was host to sports games, pageants, and military exercises. In 1925, it was also the venue of a life-sized iteration of the imagined aerial attack on London; The Defences of London reborn in open air. London Defended, this larger sequel with actual planes, was billed as a ‘stirring Torchlight and Searchlight display’.3 In the aerial bombardment, enemy airplanes (played by RAF fighter planes) were successfully rebuffed by RAF planes (playing themselves), though not before two towers on the stadium floor were set alight with incendiary bombs. The display ended with a reenactment of the Great Fire of London of 1666 during which a model of the Old St. Paul’s Cathedral was consumed by flames.

These three episodes of imagined and historical urban apocalypse—the attack on Westminster at the Admiralty Theatre, the RAF display during London Defended, and the recreation of the Great Fire of 1666—used the beauty and existential terror of sublime spectacle to instruct the audience in the conventions of British civic duty. In the face of disaster, the performances urged good morale, adherence to government decisions, and calm. This chapter demonstrates that the behavior modeled in the shows was a corrective to an underlying concern: that social chaos could emerge from the disruption of apocalyptic experience. In the aftermath of urban disasters (including historical examples such as the 1666 fire and the 1834 fire in the Houses of Parliament), there was a backlash against those who agitated for systematic social change, including religious and political dissenters. Instability and physical violence spurred a fear—on the part of politicians, the media, and the public—of internal conflict. Following the catastrophic events, it was thought, populist groups could seize the opportunity to revolt against establishment institutions. Challenges to the status quo, such as those that would materialize at the Empire Exhibition during an early worker’s strike, became a greater threat when seen through the lens of the nation’s potential vulnerability.

The Wembley exhibition ground was filled with objects that distilled imperial and civic engagement into a tangible experience. In this context, the image of the Houses of Parliament in The Defences of London was a symbol for British power.4 Yet The Defences of London and London Defended demonstrated an inward-looking fear of political and societal change that conflicted with the global assumptions of the Empire Exhibition. In this way, the themes of the displays extend the tension between the British nation and the wider world that, according to Andrew Thompson, defined the three major London exhibitions of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries: 1851, 1924/25, and 1951.5 The external narratives proposed by the exhibition were clear: Britain could eschew the typical ‘world’s fair’ because the borders of the British Empire encompassed the world. Scenarios that visualized Westminster’s destruction, however, evoked several contemporaneous threats to Britain’s social and political integrity that were also undercurrents in the spectacular optimism of the fair.

This chapter establishes that the apocalyptic performances alluded to three key conflicts: the continued reverberations of the First World War, the dissolution of Britain’s Empire, and the internal threat of class-based political disputes. The productions suggested, I argue, that without a significant change in domestic defence policies, London (or the ‘heart of Empire’ as it was sometimes called) could be physically and ideologically exposed.6 I propose that the visual depiction of the future apocalypse gained effectiveness through a relationship to historical events, including devastating fires in London 1666 and 1834 and the more recent World War I Zeppelin attacks. These occasions provided a pictorial and symbolic precedent for a future in which the same ruin could be wrought, not by natural forces or accident, but by a politically motivated attack. These shows leveraged the experience of immersive spectatorship to unify visitors, steeped in this past and aware of the geographical proximity of Wembley and London, against the unknown enemy of the future.

This chapter will first situate the visual strategies of The Defences of London in the context of the Government Pavilion and Admiralty Theatre. I will go on to show that The Defences of London responded to and extended the tropes of apocalyptic fiction, especially speculative narratives related to the Zeppelin attacks of the First World War. The performance reinterpreted these written themes in visual form. Turning to the 1925 London Defended show, I relate the full-size aerial spectacle to accounts of British aerial power in the colonial realm. The next section highlights the class conflicts of the Empire Exhibition through the 1924 Wembley worker strike. Finally, I draw on histories and images of the Great Fire of 1666 and the fire in the Houses of Parliament in 1834 to establish that natural disasters bring with them the fear of social unrest. This chapter concludes that the narratives put forth by both Wembley performances incorporated similar political implications.

‘Pictorial Realism’: The Admiralty Theatre

The Government Pavilion, home to the Admiralty Theatre, crowned one of the primary axes of the exhibition grounds. The critic for The Architectural Review noted that it served as an ‘index to the volume’ that was the exhibition.7 The colonial pavilions, like those of India or Australia, primarily exhibited raw materials, cultural artifacts, local crafts, and exported goods. The Government Pavilion, on the other hand, projected imperial might as an accomplishment of English bureaucratic hegemony. A range of government departments contributed exhibits, with topics ranging from the abolition of tropical disease to weather reporting.8 The branches of the military—the enforcer of these bureaucratic projects—also had a significant presence, which included the much-admired Admiralty Theatre.

Critics emphasized the impressive size of the Admiralty Theatre stage, which rivalled that of Covent Garden. They were, however, careful to tout its practicality. The Times wrote

One can scarcely believe that the stage of the Admiralty Theatre is among the largest anywhere … But scepticism gives way under the figures of actual measurement. The Wembley stage looks relatively small because unnecessary top space is cut away. It is a model, as some hold, of the stage of the future—long, low, workmanlike.9

As the venue for reenactments of historical battles, in addition to the speculative drama of The Defences of London, it was necessary to distance the Admiralty Theatre from the entertainment of conventional theatre. The ‘workmanlike’ stage could, instead, immerse its audience in a substantive pedagogical narrative and perform a role in educating British citizens.

The Times also pointed to the advantage that the Admiralty Theatre enjoyed over the new technology of the moving picture. They claimed that its dynamic interplay of light, sound, and image overcame the sensorial lack inherent in black and white cinema.10 The Government Pavilion planning committee evidently agreed, and they scrapped a plan for a separate cinema in favour of centralizing programs in the Admiralty Theatre.11 In the Admiralty Theatre, the magic of the stage lights created atmospheric effects—moving clouds and rays of sunshine—that bolstered the verisimilitude of the scene. These illuminations were augmented by electrically powered objects carried around the stage on rails, which were moved remotely from a board in the control room. An image of the theatre in The Illustrated London News showed the hidden control panels filled with complicated buttons and knobs (Fig. 1).12 The complexity of the scene recalls the interior of a warship or plane, showing entertainment as a mirror of the command centres of battle.

The Admiralty Theatre performance that most captured the attention of the press was the reenactment of the World War I naval battle of Zeebrugge. The action took place on the Theatre’s water stage and the boats moved about on submerged rails. On stage, the dynamic texture of the water was augmented by smoke machines, lights, and off-stage sound effects. A live orchestra provided dramatic musical accompaniment.13 As the battle raged, a narrator explained the movement of the British and German ships while text and images were projected onto an accompanying screen. The scene introduced an intimate experience of war and was calibrated to appear as if the audience stood upon a naval ship three miles offshore.14 Outside the Admiralty Theatre, there were a set of more conventional panoramic models of the First World War which depicted battles at Ypres, the North-West Frontier of India, and Messines Ridge. These were the nineteenth-century ancestors of the theatre, pioneering the multimedia approach that would bring the Battle of Zeebrugge to life.

In the Admiralty Theatre performances, the panorama met conventional theatre and technological advances in electricity to create a unique all-encompassing experience.15 In preparation meetings for the Government Pavilion, members of the interdepartmental planning committee carefully distinguished between the experience of viewing events as models and as performances in the Admiralty Theatre. The ‘more spectacular events’, they concluded, would be better suited to the immersive Admiralty Theatre.16 This was an effective strategy, and The Times wrote ‘it makes one rapacious for a similar sight of every memorable action, naval and military, in our history. Never was there such pictorial realism in any theatre’.17 ‘The spectacle’, The Times concluded, ‘seems less a reproduction of what happened than a resurrection’.18 Such ‘pictorial realism’ defined an experience of collective spectatorship that imbued theatregoers, many of whom had no first-hand experience of the terrors of the Great War, with an illusion of battle-hardened nationalism. If the resurrective capacity of the theatre could bring history to life, it could also be used to imagine future events.

The Defences of London was the War Office and Air Ministry’s contribution to the rotation of performances in the Admiralty Theatre. It was unique in its form, its focus on the domestic sphere, and its evocation not of a historical event, but a potential threat. The pictorial realism of the Battle of Zeebrugge was redirected towards a speculative future. To include the The Defences of London was a striking choice on the part of the War Office and Air Ministry and it challenged the careful political calculations of the Government Pavilion. The planning committee was concerned with producing a unified message, and often reminded the various departments involved that they were required to ‘ensure that the nature and presentation of any exhibits or displays are unobjectionable on political or general grounds’.19 Yet, during a February 1924 meeting, the committee discussed the fact that ‘possible objections may be raised to the inclusion … of an imaginary air attack on the House of Commons’. The politics of the display had come close to flouting the committee guidelines.20

While contemporaneous newspaper accounts, including The Times and The Illustrated London News, detail the technical specifications for the water stage and the reenactment of the Zeebrugge raid, they did not record the theatre’s transition to the attack on Westminster.21 However, models of the Houses of Parliament were ordered for the stage, which makes a similar combination of miniatures, lights, film, and explosives the likely tools of the The Defences of London.22 To convert the theatre from the Zeebrugge Raid, the water stage was covered and replaced with a miniaturized model of the Westminster skyline as viewed across the Thames from the London City Council building.23 Like the placement of the viewers of the Zeebrugge raid three miles out to sea, the set designers carefully chose a realistic vantage point for the audience to take in the scene.

The Illustrated London News published a drawing and description of the scene on July 19, 1924:

Lights go up in the House of Commons. A moment later there is a faint rumble, and there are strange flashes in the sky. Raiders are coming, and they are already dropping bombs. With little to hinder them—nothing but a few anti-aircraft guns, position-revealing searchlights, and fighting aeroplanes in insufficient numbers—they sweep and swoop over the city, and their bombs still the heart of Empire, leaving it a blackened, shrivelled, useless thing.24

The accompanying illustration presented the moment of final disintegration (Fig. 2). Swirling smoke tinged with fiery pinks and reds draws both the audience and the newspaper reader towards the strange beauty of destruction. Yet the raiders themselves are gone from the sky and the viewer is left to imagine the presence of the enemy. While the outline of Big Ben remains intact, it only serves to emphasize the ruin of the Houses of Parliament. The neo-gothic edifice is crumbled and skeletal, still consumed by fire. Hazy light from the smoke-filled screen falls on the audience. It most visibly highlights the profile of a well-dressed woman in a red hat who, enthralled, raises her hand to her mouth. For women like her (who had probably never seen the battlefront), the radical dissolution of familiar space was intended to produce a dramatic immediacy. It transposed the experience of war gleaned from the static dioramas of Ypres and the Somme, which sat just outside the theatre, into the present moment. The imminence of ‘resurrection’ turned this conjectural event into something resembling lived history.

The Air Ministry intended to use the emotional reaction to this dystopian drama to increase support for national air defence. The headline from The Illustrated London News concentrated on this aspect of the event, declaring ‘Wembley Presents the Case for Air-Raid Defence: A Dramatic Object Lesson, in the Government Building’.25 The Defences of London argued that the horror of war could quickly enter the home front. The message was made clear through the second half of the program, which saw the skyline saved by the efforts of the Royal Air Force. Because of this intervention, the program concluded with the Houses of Parliament and Big Ben intact (likely much to the relief of the woman in the red hat).

However, in 1924 there was no comprehensive aerial defence force and, like the entire show, the denouement was only an imagined alternative scenario. Aerial defence was a contentious issue in the 1920s. Brett Holman points out that between the First World War and the early 1920s, military theorists and political commentators, including RAF officers and amateur airpower strategists, advanced the theory of the ‘knock-out blow’ as an existential threat to the home front.26 The concern was that an enemy force could plan a surprise air raid to preempt the declaration of war. Bombing in London and major industrial areas would limit production capacity, confuse the government response, and lower the morale of the civilian population. The enemy could essentially win a war before it began.27 In 1924, without a defending air force, Britain seemed unprepared for the demands of future aerial combat.28

The German Zeppelin raids of the First World War were a key precedent for the knock-out blow theory and had piqued anxiety about the threat to civilian populations in modern warfare. With these attacks, the Germans aimed to diminish morale and disrupt the noncombatant labour force. Whereas locations distanced from the battlefield had previously been protected, these air raids, as Susan Grayzel argues, created the notion of the home front as its own sphere of battle.29 The German Zeppelin raids in London began in March 1915 and took place sporadically throughout the First World War. The bombs caused visible damage, with over five hundred people killed and various English towns and cities sustaining damage. However, the technological limitations of the Zeppelins and the novelty of air attacks, as Ariella Freedman has pointed out, made the imagined threat of the raiders more significant than the reality of their reach.30 Crucially, as Grayzel notes, the bombs disrupted the feeling of safety previously borne of England’s island geography. Civilians could now face the same danger as soldiers at the front.31

Compared to conventional warfare, however, the tools of aerial bombardment were diffuse and mysterious. The Zeppelins flew high above the ground and this distance prompted many contemporaneous observers, according to Freedman, to liken them to weather or gods rather than tools of earthbound combat.32 In this way, I argue, aerial bombardment took on the mantle of potential apocalyptic destruction previously reserved for natural disasters and acts of God. An encounter with the flying instruments of war was similar to the terror of the sublime.33 These machines represented a future in which technology could challenge geographical boundaries and the patterns of warfare.

The technological intrigue of aerial warfare provoked conjecture about the dystopia that it could create. Martin Ceadel, Uri Bialer, and Christopher Simel have shown that these fears were codified through both changes in government policy and contemporaneous cultural interpretations in art and literature.34 Because of the unprecedented nature of the Zeppelin raids, they contend, these cultural reactions are significant historic documents. The aerial turn played out in the public sphere and, as a result, demanded a robust cultural response. This included, I argue, The Defences of London and London Defended. Bialer underscores the scholarly relevance of inventions such as these, asserting that there was little difference between the administrative responses to the potential crisis of aerial warfare and the scenarios put forward in speculative literature.35 To this end, literature scholars have identified a body of interwar science-fiction and futuristic writing that directly responded to Zeppelin raids and the aerial threat.36 While there is less evidence of this trend in performance or the visual arts, the capacity of the Admiralty Theatre for lifelike resurrection made it an ideal venue for evoking the dystopian possibilities of aerial combat.

The Defences of London, facilitated by the advanced technology of the Admiralty Theatre, made the potential destruction of the city tangible in order to attune audiences to the importance of home defence. In addition, however, the aerial spectacle could have aided the Air Ministry itself in envisioning the form of a future aerial apocalypse. John Ferris points to the theoretical nature of aerial warfare in the interwar period. He quotes the 1934 Chief of Air Staff, who noted that

The RAF had to rely on ‘pure guess-work’ and ‘arbitrary assumptions’ about every detail of strategic air warfare, ‘as we have no practical experience of air warfare on a major scale under modern conditions to provide us with definite conclusions capable of mathematical expression’.37

These circumstances bolster Bialer’s argument that in the novel sphere of aerial warfare the line between professional analysis and the larger cultural imagination was blurred. The Defences of London used the Admiral Theatre’s ‘pictorial realism’ to instruct the audience. It also could have given concrete form to the elements of ‘pure guess-work’ that defined the RAF’s preparation for the modern conditions of air warfare. ‘Nothing could illustrate more realistically what might happen to London were it inadequately defended in time of war’ wrote The Illustrated London News.38 This level of realism could have helped both the audience and the RAF understand and plan for an otherwise inscrutable future. The visual power of the Admiralty Theatre made the speculative future real.

‘Their bombs still the heart of Empire’: Air Power and Empire

If the unknown fighters in The Defences of London evoked the recent history of German Zeppelin aggression, the air battles depicted at the Empire Exhibition also recalled the RAF’s engagement in the British Empire. After the First World War, many RAF fighter planes and bombers were quickly redeployed around the empire to control British colonial interests.39 The planes had a significant tactical advantage over infantry troops. The RAF could cover large swaths of unpredictable topography and could be deployed from a limited number of bases, which required a smaller commitment of manpower. A military presence in the colonial realm was especially important for Britain because of growing nationalist movements in India and the Middle East, which were encouraged by the upheaval of World War I and the Communist revolution in Russia.40 Faced with the threat of losing previously stable colonial holdings, the British reallocated their military assets to foreign soil instead of focusing on the home front.41 Air control was essential to imperial stability.

A performance in which Westminster (as a symbol of the Golden Age of British colonialism) was destroyed spoke to a broader concern over Britain’s role in the twentieth-century world. ‘Their bombs still the heart of Empire,’ The Illustrated London News intoned, ‘leaving it a blackened, shrivelled, useless thing’.42 Despite the confidence expressed by the Empire Exhibition, the early 1920s saw a slew of significant changes in Britain’s imperial role. While the decade following the Second World War was the apex of decolonisation, changes in world politics after the First World War brought Britain’s global dominance, and the internal relevance of the empire, into question. The heart of empire was susceptible to a future in which it might be ‘blackened, shrivelled [and] useless’.43

The territorial peak of the British Empire was in 1921.44 As the decade progressed, however, multiple instances undermined Britain’s identity as the invincible global power put forth by the Empire Exhibition. Tensions with Ireland, independence movements in India, the end of the British protectorate in Egypt in 1922, and the 1923 creation of the Commonwealth were all an uneasy backdrop to the imperial performance of the Empire Exhibition.45 Alexander Geppert argues that tensions between Britain and the colonial nations manifested in the operation of the exhibition, as bureaucratic conflicts broke out between the exhibition’s organizers and the administrators of the colonial pavilions.46 This was, he writes, an early sign of imperial dissolution. At the same time, the imperial project as a cornerstone of British identity was being challenged internally by left-wing and communist groups, who, as Sarah Britton demonstrates, wrote and rallied in opposition to the imperial project represented by this kind of exhibition.47

In the second year of the Wembley Exhibition, which opened in May 1925, most of the programs remained in continuity with 1924. Exhibitions of timber stayed in the Canadian pavilion just as the world relief map and Admiralty Theatre remained in the Government pavilion.48 The Empire Stadium, the large sports and performance arena that anchored the exhibition grounds, continued its program of Torchlight Spectacles. These were a series of nighttime shows in the stadium that used music, performers, monumental lighting effects, and aeroplane flyovers to create a spectacular variety show.49 To that end, the 1924 Wembley Torchlight Spectacle included an RAF performance in the guise of an air battle.50 In 1925, however, the show reappeared as London Defended, a life-size reprisal of an aerial attack against the London skyline.51 In a departure from the 1924 Torchlight Spectacle, the audience would now see aerial combat in their home city.

The success of The Defences of London in the Admiralty Theatre may have spurred the expansion of the performance into London Defended the following year.52 The 1925 performance showed a similar raid on London from unnamed enemy aeroplanes. However, as the promotional brochure highlights, instead of the miniatures and magical projections of The Defences of London, London Defended included full-size searchlights, real air fights, and simulated bombs.53 The cover of the program shows aeroplanes dramatically silhouetted against the dark sky. Wembley Stadium and its bright searchlights glimmer below. If the Admiralty Theatre was praised for the immersive products of its stage management techniques, the Empire Stadium promised yet greater thrills. The drama of London Defended was intensified by the sights, sounds, and vibrations of actual RAF planes. The spectacle also included a display of horsemanship by the Metropolitan Mounted Police, a two-hundred-person choir, and military marching bands.54 The Admiralty Theatre took its cue, but then departed from, conventional theatre. Similarly, the RAF section of the London Defended program, which included both ‘aerial acrobatics’ and a simulated defeat of an enemy air attack, related to another familiar format that was intimately related to imperial politics: the air show.55

Fictitious RAF spectacles were institutionalized in annual displays at Hendon Air Base located outside London to the northeast of Wembley.56 These performances used elaborate sets and costumed actors to transport the viewer into various spheres of combat. The focus on foreign combat—first Germany and then Middle-Eastern colonies—was an important precedent for the internal threat detailed in London Defended. The yearly series at Hendon began in 1920, following the end of the First World War. There was a similar audience base for the Hendon shows and the Empire Exhibition, as there is an advertisement for the June display at Hendon in the 1925 booklet for London Defended.57

While Hendon also promoted a program of aerial stunts, an aeroplane race, a bombing attack, and an air battle, the domestic location of the action in the London Defended show was a notable departure from the Hendon series. The Hendon Aerial Pageants in 1920 and 1921 directly referenced the First World War, with scenes set at the Front and in enemy territory – comfortably far from London. Trenches were bombed in 1920 and in 1921 organizers built a German village out of scrap metal.58 During the performance, the village was destroyed by RAF bombers. In 1922 and 1923, the action shifted to the imperial realm; bombings now took place in simulations of Britain’s Middle Eastern colonies.59 Just as the 1920 and 1921 shows were preoccupied with the German military, this new geographic focus reflected the political debate over the RAF’s role as an enforcer in the British Empire. The 1922 Hendon spectacle turned away from the near history of World War I toward the future represented by imperial dominions.60 Hendon shows the extent to which entertainment mirrored foreign policy priorities, and these performances used the threat of imperial insurgence as justification for military exercises in the colonial realm. While the Hendon shows pivoted to the colonies, the 1925 air display in the Empire Stadium at Wembley looked inward.

London Defended recreated a domestic urban scene, and a large tower was built on the stadium floor.61 Unlike the sets at Hendon, however, the recreation was a sight much closer to home for most viewers. Unlike the first act of The Defences of London, the enemy attack in this performance was met with some domestic defence. There were anti-aircraft guns and searchlights, each adding to the impressive quality of the nighttime event.62 The audience would have heard the planes approaching the stadium. At Hendon, the enemy had been clear – German uniforms were easily recognizable just as the architecture of the 1922 show signalled the Middle East. In the darkened Empire Stadium, however, the identity of the enemy remained elusive. Like the Zeppelin raiders of the First World War, the planes were high up, mechanical participants rather than costumed actors. The raiders coming could be anyone, from anywhere. The omission of a specific identity heightened the drama while simultaneously dispersing the identity of the opposing force.

When searchlights picked up the enemy planes in the stadium, the drama increased. An airfight ensued and the RAF was victorious. The enemy bombers, however, left the tower on the stadium floor in flames. The London Fire Brigade saved the day through their modern fire-fighting methods.63 Just as the Admiralty Theater transformed from the site of foreign battles (such as the Battle of Zeebrugge) to one of internal destruction (The Defences of London), the RAF spectacle pivoted from Hendon’s imperial dramas to the domestic menace of London Defended. Despite the imperial focus of the Wembley exhibition, in this performance, the triumph of British aerial power abroad was challenged by the necessity of home defence.

The ‘Wembley Squint’: Class Conflict at Wembley

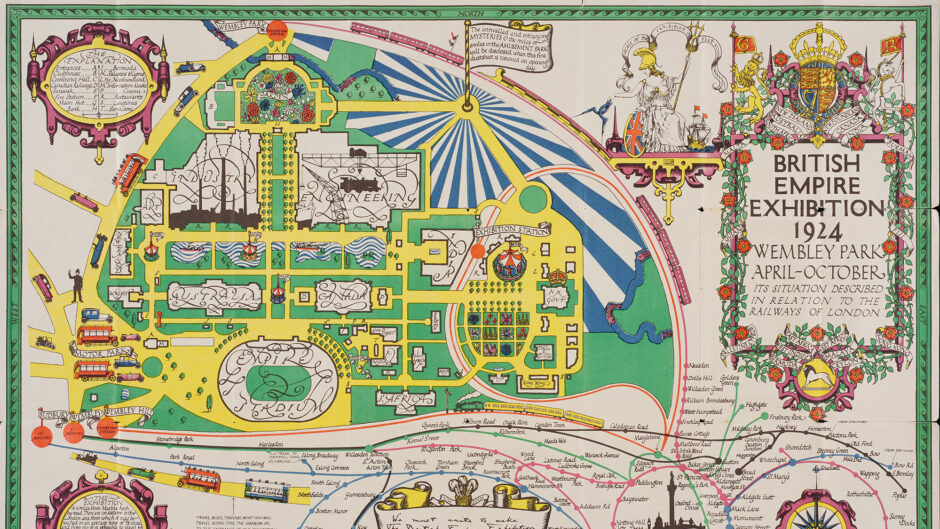

If the Exhibition was intended to signal Britain’s imperial accomplishments on a global stage, it also attempted to recapture the attention of the British working class. As Geppert points out, the suburban location of Wembley and the amusement-park style fair attractions encouraged working- and middle-class visitors to take part in the imperial project.64 An official map of the exhibition grounds drawn by Kennedy North heightened the exotic drama of the peripheral town (Fig. 3). North’s drawing used tube routes to connect London and Wembley. The brightly coloured lines tied the fairgrounds to a stylized image of the London skyline. Beneath a banner reading ‘The Heart of Empire’, Nelson’s Column rises above the geographically outsized forms of Westminster, St. Paul’s Cathedral, and the Tower Bridge. For British citizens unable to travel to the outer reaches of the empire, the empire could come to them in the capital city.

North’s map shows the gaily festooned tents, lush gardens, and enticing pavilions from colonies ranging from Burma to the Gold Coast. This visually cohesive space belied the fractures in both the colonial and domestic realm. Visitors to the exhibition were often enthralled by these performative aspects of imperial identity. This was a calculated strategy intended to implicate members of the working- and middle-classes in the commercial project of the empire.65 But the experience was sometimes overshadowed in the public imagination by the accusations of financial mismanagement that dogged the exhibition.66 Organizations such as the Trade Unions Congress and Labour Party Executive recorded their frustration with what they saw as a fundamental contradiction between the principles of the Commonwealth and the working conditions of the fair.67 They highlighted the contrast between the significant cost of the pavilions and the low pay and poor working conditions for those who built and operated the fair.

The concern over labour rights in the exhibition was a challenge for Britain’s first Labour government under Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald, who took office in January 1924 three months before the exhibition opening.68 In winter 1924, the future of Wembley was imperilled by a strike. It began with a group of electricians agitating against non-union labour employed by exhibition organizers, but the protest soon expanded to encompass wage disputes and workplace safety.69 Newspapers reported that the strike would likely slow the opening of the Empire Exhibition.70 The Wembley strike was part of a larger effort by labour groups to develop the power of unions across geographic areas and sectors, and the electricians were soon joined by plasterers and carpenters.71 As was the case with many collective actions of the time, the local police force was called in to protect the exhibition grounds from the supposed threat.72 A photograph of the strike shows exhibition workers milling around a construction site strewn with raw stone slabs, lumber, and dirt (Fig. 4). A large group of policemen looms above them. In the background, the skeletal towers of various pavilions under construction highlight the stakes of the conflict. The image triangulates between the idle workers, the arm of the law, and the unfinished buildings, using the contrast to put forth a narrative that political radicalism was obstructing the core mission of the exhibition.

In the House of Commons, Members of Parliament invoked patriotism and imperial unity to compel the strikers to restart the construction process.73 Though MacDonald’s government was generally cautious about imperialistic displays, the fact that funds had already been poured into the construction from private individuals, dominion governments, and the British government made it politically vital that the work on the exhibition continued.74 The British Empire Exhibition was an important symbolic centre. Though the Labour government valued the exhibition’s focus on industry and production, the Communist Party saw an opportunity to expose the poor treatment of British workers.75 Communist organizers wanted a public demonstration that imperial success was contingent upon the labour of the worker, in Britain and abroad.76 What better venue, they reasoned, to jumpstart a national effort for worker’s rights? Implicit in this critique was distrust in the political project of empire writ large.77 In September 1924, T.A. Jackson, writing in The Communist Review, noted the hypocrisy of an empire made up of disenfranchised subjects supposedly united under a democratic Parliament. 78 Jackson termed this fallacy the ‘Wembley Squint’, stressing that the exhibition enforced the idea of the empire as a positive global force rather than a complicated political entanglement.79

Opponents of the union strike, including Conservative news sources and politicians, argued that the strike demonstrated the inconsistency between Communist allegiance and British citizenship. Moreover, despite the efforts of the Labour government to bring the strike to a satisfactory conclusion, right-wing publications implicated them in the goals of the Communist party. The fears stoked by some Conservative publications and politicians lay in the impression that, in the aftermath of the 1917 Russian Revolution, sympathy to the rights of the working class would lead to a transnational Communist takeover. In describing the 1924 strike, the unionist Belfast Telegraph wrote ‘The strike at the British Empire Exhibition Wembley is the latest eruption of the spirit of unrest that is abroad, illustrating the tactics of the small, but ceaselessly active band of Communists who are carrying on propaganda inside the trade unions’.80

The Northern Whig and Belfast Post speculated that the Communist Party, working at the behest of Moscow, had supported the Labour party’s rise. Now that Labour was in power, the unions were leveraging the ‘sinister events at Wembley’ to incur a full-scale revolution.81 The small group thought to be disrupting the undertakings of the Empire Exhibition became an allegorical shorthand for the Communist threat to the British Empire as a whole. In this politically charged climate, the conflagration of the seat of government (Westminster, and then London itself), gained another layer of meaning. Taken in tandem with the nationalistic narratives derived from the story of the 1666 Fire of London, which I will discuss shortly, I argue that the implied faceless threat to Britain’s capital in these apocalyptic scenes could be conceived as a warning about internal political dissent, shown starkly against the backdrop of Wembley’s striking workers.

After the First World War, members of the Labour party questioned both the morality of a protracted aerial campaign in the colonial realm and the wisdom of engaging in an aerial arms race with other nations.82 After the Labour party victory of 1923, Conservatives argued that this attitude in a sitting government would undermine the safety of Britain. In the first weeks of March 1924, as the final plans for the British Empire Exhibition were being executed, both the House of Commons and House of Lords debated the government’s commitment to aerial infrastructure. The Marquess of Londonderry and Sir Samuel Hoare, both of the Conservative Party, introduced a motion for the Government to affirm their dedication to maintaining a substantial domestic air force. Though the Labour Secretary and Under-Secretary for Air firmly stated that the government would support a reasonable growth policy, many remained suspicious of these claims.83

The Labour party’s supposedly willful resistance to domestic air defence was the chief plot point of The Battle of London, a novel first published in fall 1923 by Harry Collinson Owen, writing under the pseudonym Hugh Addison.84 The Battle of London tapped into the cultural concern over aerial warfare and documents how the aerial threat was manipulated to fit a variety of political goals. In contrast to the German threat from H.G. Well’s The War in the Air or the imperial concerns of Hendon, the enemy in this narrative was the British Communist Party. Owen leveraged the same symbolic triggers that would appear in The Defences of London: The Houses of Parliament burned in an aerial apocalypse.

Owen’s book collected alarmist discourses over imperial decay, Communism, and the aerial menace from Germany into one symbolic centre – Westminster. In the denouement of the novel, the Germans seized the opportunity of civil war to attack London.85 The ensuing aerial raid decimated the Houses of Parliament, as it would in The Defences of London. Owen’s insinuation that the debate on aerial defence would lead to this future conflict was clear to readers. The Battle of London, one reviewer noted in November 1923 ‘Can be read with advantage in these election days. Bolshevism, it is argued, can be met and conquered chiefly by the efforts of the citizens themselves’.86 To protect the country from internal (Communist) and external (German) threats, it was incumbent upon Owen’s reader to ensure a Conservative victory. While Owen’s book is an extreme example, any performance that argued for increased domestic air defence, as did The Defences of London, evoked these public political debates.

Sublime Conflagration

The drama of ruin and redemption in The Battle of London and The Defences of London had precedent in the Great Fire of London of 1666 and the burning of the House of Commons and House of Parliament in 1834. The vision of Westminster obscured by fiery smoke in The Defences of London recalled popular prints and paintings of the 1834 fire, which circulated widely in the nineteenth century. Artist JMW Turner was an eyewitness to the fire, and his depictions of the event were particularly notable for their dramatic beauty. The concept of the sublime was a key tenant of eighteenth-century British aesthetic theory and the sublime object or vista incorporated both horror and beauty. It could fascinate and attract the observer against their will, lending even terrible destruction the role of a spectacle. Just like Turner’s depictions of the 1834 disaster, The Defences of London demonstrated the emotional power of apocalyptic spectacle.

The scene of The Defences of London that was illustrated in The Illustrated London News had a strikingly similar framing to Turner’s paintings of the event, both titled The Burning of the Houses of Lords and Commons October 16, 1834 (Figs. 5 and 6). In The Defences of London and The Burning of the Houses of Lords and Commons October 16, 1834, Westminster is viewed from across the Thames. These images all use the dark water to reflect the uncanny brightness of the fiery scene. In The Burning of the Houses of Lords and Commons October 16, 1834, the red light of the fire animates the human figures who line the bank, implicating the rapt viewers in the terrible event. The Illustrated London News similarly positions the experience of the spectator as a vital aspect of destruction. At the Admiralty Theatre, the magic lights and real smoke bring the Wembley visitors into the events unfolding on the stage. Unlike the organizers of The Defences of London, however, Turner was disinterested in individual emotional response. Rather, he depicts the spectators— or the mob, as some accounts portrayed those watching the fire— as a natural force unto themselves.

The 1834 fire was started to dispose of wooden tally sticks, an obsolete form of tax records. It soon burned out of control and the flames overtook the Parliament buildings.87 That these bureaucratic materials destroyed the seat of government was an irony not lost on contemporary commentators. As an article from The Morning Herald highlights, some, however, saw a more nefarious subtext in the events.88 In the aftermath of the fire, some newspapers voiced a fear that the disaster was a destabilizing force that would facilitate the growth of dissident movements. Subversive elements, they believed, could manipulate the public response to the violent destruction. In the days after the fire, The Morning Herald called attention to the mystery of the fire’s unknown origins and the strange fact that no one had raised the alarm until much of the building was already aflame.89 While the article conceded that there was no implication whatsoever that it was a case of arson, the paper nevertheless cast a group of onlookers as suspicious villains of the drama: ‘Our accounts from the scene of destruction inform us that the mob, upon witnessing the progress of the flames, raised a savage shout of exultation’.90 The massed onlookers in Turner’s paintings seem to embody the chaotic power of the urban spectacle.

The phrase ‘mob’ was a weighty one in 1834.91 It evoked the spectre of working-class revolt, both in the context of foreign revolutions in France and America and more recent riots in Britain.92 Alighting on the largely fictitious celebrating mob as complicit in, if not responsible for, the annihilation of a building that represented centuries of British political history, The Morning Herald weaponized existing paranoia about the power of the working class. The unpredictable reaction of the crowd to urban apocalypse, represented by The Morning Herald’s cheering mob, was also a consideration for the Air Ministry in the 1920s. Grayzel argues that RAF studies of the public attitude towards Zeppelin raids demonstrated a belief that the ‘others’ in the city—the poor, immigrants, or Jews—were constitutionally unfit to deal with aerial threats.93 Official reports implied that the lack of morale could, itself, be a significant threat to a future war effort. Ferris also notes that RAF officers ‘held [that] bombing would spark upheaval among ‘volatile’ peoples’.94 The instability of the ‘volatile’ crowd in the aftermath of disaster could prove as destructive as the falling bombs.

In addition to raising awareness about domestic defence, The Defences of London and London Defended prepared viewers for the possibility of future aerial attacks. By exposing the British public to the threat of domestic disturbance within the controlled setting of the Empire Exhibition, the performances encouraged the audience to maintain equanimity in the face of attack and to trust in the government’s military strategy. Political dissent, however, took on a further layer of menace. In the apocalyptic future, strikes (like the one that stalled the early construction of Wembley), anti-imperial advocacy, and immigrant communities could be perceived as threats that could fracture society. Britain’s social structure could be susceptible to both the distant enemy and the internal one.

The final act of London Defended opened with a scene of the city in the seventeenth century. A baker’s shop was ablaze, an echo of the tower burned down by the aerial raid earlier in the show.95 This was the 1666 Great Fire of London. If The Defences of London gestured obliquely to the fire of 1834, London Defended explicitly linked the danger of aerial raids with this historical catastrophe. In the seventeenth century, the large-scale destruction of the city quickly became an exemplar of God’s wrath, with preachers and laypeople alike drawing comparisons to the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah.96 Nature was, in this telling, wielded as a tool of divine judgement. The parliamentary investigation of the 1666 fire deemed that it was evidence of ‘the hand of God upon us, a great wind and the season so very dry’ and ascribed the event to nature’s inscrutable power.97

However, some news accounts characterized the fire as an intentional attack.98 Treachery and conspiracy were common concerns as tensions in England ran high due to sectarian violence and the ongoing wars in Europe. Guy Fawkes’ attempt to blow up the Houses of Parliament had taken place sixty years earlier and remained a symbol of Britain’s religious divisions. As the fire raged through London’s streets, rumours spread about a Catholic attack on the city.99 In 1666, England was also at war with France and the Netherlands, and these conflicts spurred intense xenophobia. The London Gazette reported in the aftermath of the fire that ‘Diverse strangers, Dutch and French were, during the fire, apprehended, upon suspicion that they contributed mischievously to it, who are all imprisoned and information prepared to make a severe inquisition’.100 Like The Morning Herald in the days after the burning of the Houses of Parliament, the London Gazette took advantage of the opportunity to push their political agenda. The seventeenth-century disaster, just like the RAF’s analysis of London’s urban population, bred a reaction against what the establishment perceived as threatening and undesirable elements: the foreign and the politically deviant. In the days after the fire, this manifested in violent attacks on foreign citizens living in London.101 Disaster was, in each of these real and imagined events, entwined with anxiety over the hidden internal threat.

London Defended ended with a message that celebrated national unity. When the enemy planes were defeated and modern firefighters subdued the flames of the 1666 fire, a final scene showed King Charles II visiting a camp of displaced London citizens.102 A brochure of the production explained, ‘As he arrives the smoke is transmuted into a blue haze, through which shines the dome of the new St. Paul’s with its golden cross’.103 The hallucinatory image of this scene, with the two versions of St. Paul’s rising out of the smoke, adorned much of the show’s promotional material (Fig. 7). In this juxtaposition, the resilience of modern England was concrete and immutable. The continuity of the royal line, between King Charles II and George V, and the consistency of geographical space, with the two iterations of the Cathedral, implied a stable narrative that overcame even drastic destruction. The propaganda value of this image, which obliterated political strife and imperial decline, belied a future apocalyptic moment where the worry over aerial attacks was incontrovertibly real.

Conclusion

Just fifteen short years later, the famous blitz photograph ‘St. Paul’s Survives’ taken by Herbert Mason in December 1940 had an almost identical framing to the 1925 print – the dome of the Cathedral rising above the shells of burning buildings. Mason’s photograph was used in Britain as an image of resilience.104 ‘War’s Greatest Picture’ the Daily Mail proclaimed, ‘St. Paul’s Stands Unharmed in the Midst of the Burning City’.105 The symbolic juxtaposition of Cathedral and smoke was an obvious one in both 1925 and 1940. Britain would, like a phoenix, rise from the ashes. But who, the performances of the British Empire Exhibition demanded, is part of that rebirth? What place do the rapt spectators, or the unruly mob, play in the reintegration of postwar Britain? The dystopian fictions of the British Empire Exhibition showed the enduring power of apocalyptic imagery in the British imagination—through 1666, 1834, 1924, 1925, and 1940—in uniting a populace in nationalistic fear and awe. These scenes, however, betrayed a political subtext to both natural disaster and acts of war. Apocalypse renders vast societal shifts, pushing some to embrace ruin and destruction in an attempt to excise opposing views from the public realm.

Citations

1 In addition to the public enthusiasm for the second year of the exhibition, there was a complicated financial calculation in the reopening. The initial output on the exhibition grounds was so significant that the first year of the fair lost money. In reopening in 1925, the government, who had taken on financial responsibility for the event, hoped to recoup some of their investment.

2 Many aspects of the Imperial politics evident in the Exhibition have been addressed by scholars including Anne Clendinning, ‘On The British Empire Exhibition, 1924-25.’ BRANCH: Britain, Representation, and Nineteenth-Century History, (2012), accessed 8 October 2021, http://www.branchcollective.org/?ps_articles=anne-clendinning-on-the-british-empire-exhibition-1924-25; Deborah L. Hughes ‘Kenya, India and the British Empire Exhibition of 1923.’ Race & Class 47:4 (2006): pp. 66-85; David Simonelli, ‘“[L]Aughing Nations of Happy Children Who have Never Grown Up”: Race, the Concept of Commonwealth and the 1924-25 British Empire Exhibition’, Journal of Colonialism & Colonial History 10:1 (Spring, 2009); Daniel M. Stephen, ‘“The White Man’s Grave”: British West Africa and the British Empire Exhibition of 1924-1925’, Journal of British Studies 48:1 (2009): pp. 102-128.

3 London Defended: Torchlight and Searchlight Spectacle (London: Fleetway Press, 1925).

4 Tony Bennett argues that, from the nineteenth century, the visual power of worlds fairs and exhibitions was used to impress systems of knowledge upon visitors. Fairgoers were given easily digestible narratives of the world through the objects that they encountered in the exhibitions. The ideological power of these objects gave tangible form to otherwise abstract concepts. Bennett famously termed this system the ‘exhibitionary complex.’ Tony Bennett, The Birth of the Museum: History, Theory, Politics (London; New York: Routledge, 1995), pp. 59–88.

5 Andrew Thompson, ‘“A Tale of Three Exhibitions”: Portrayals and Perceptions of ‘Britishness’ at the Great Exhibition (1851), Wembley Exhibition (1924) and the Festival of Britain (1951),’ in Gilbert Millat (ed.), Angleterre ou albion, entre fascination et repulsion: de l’Exposition universelle au dome du millenaure, 1851-2000 (Université Charles-de-Gaulle-Lille III, 2006).

6 Regarding the importance of the term ‘heart of Empire’ in the context of the British Empire Exhibition, Alexander Geppert points to the intertwined relationship between London and Wembley. He emphasizes, however, that Wembley was ultimately a suburban site that remained at a remove from the capital city. Alexander C. T. Geppert, Fleeting Cities: Imperial Expositions in fin-de-Siècle Europe (Hampshire, England: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), pp. 144-145.

7 Harry Barnes, ‘The British Empire Exhibition’ Architectural Review, 1 (1924), pp. 208-217.

8 Guide to the Pavilion of His Majesty’s Government: British Empire Exhibition 1925 (London: H.M. Stationery Office, 1925).

9 ‘Huge Stage at Wembley’, The Times, June 27, 1924.

10 ‘Huge Stage at Wembley’.

11 Minutes of meeting discussing government participation in the British Empire Exhibition, January 23, 1924, MT 9/1602, The National Archives, Kew, United Kingdom.

12 ‘Storming Zeebrugge at Wembley’, The Illustrated London News, May 24, 1924.

13 Minutes of meeting discussing government participation in the British Empire Exhibition, March 14, 1924, MT 9/1602, The National Archives, Kew, United Kingdom.

14 ‘Storming Zeebrugge at Wembley’.

15 Erkki Huhtamo, Stephen Oettermann, and Denise Oleksijczuk each describe the history of the panorama in the United Kingdom. Huhtamo’s account of the relationship between panoramas and media culture is especially relevant to the genealogy of the Admiralty Theatre performances. Erkki Huhtamo, Illusions in Motion : Media Archaeology of the Moving Panorama and Related Spectacles (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2013); Stephan Oettermann, The Panorama: History of a Mass Medium, (trans.) Deborah Lucas Schneider (New York: Zone Books, 1997), pp. 99–142; Denise Blake Oleksijczuk, The First Panoramas: Visions of British Imperialism (Minneapolis and London: University of Minneapolis Press, 2011).

16 Minutes of meeting discussing government participation in the British Empire Exhibition, July 5, 1923, MT 9/1602, The National Archives, Kew, United Kingdom.

17 ‘Seeing the World, The Government Pavilion’, The Times, May 24, 1924.

18 ‘Seeing the World’.

19 Minutes of meeting discussing government participation in the British Empire Exhibition, November 14, 1923, MT 6/1602, The National Archives, Kew, United Kingdom.

20 Minutes of meeting discussing government participation in the British Empire Exhibition, February 28, 1924, BT 60/5, The National Archives, Kew, United Kingdom.

21 ‘Storming Zeebrugge at Wembley’; ‘Huge Stage at Wembley’.

22 Admiralty Tank Budget, MT 9/1602, The National Archives, Kew, United Kingdom.

23 ‘Wembley Presents the Case for Air Raid Defence’, The Illustrated London News, July 19, 1924.

24 ‘Wembley Presents the Case for Air Raid Defence’.

25 ‘Wembley Presents the Case for Air Raid Defence’.

26 Holman, The Next War in the Air, pp. 23-24.

27 Holman, The Next War in the Air, pp. 38-39.

28 Holman, The Next War in the Air, p. 129.

29 Susan R. Grayzel, At Home and under Fire: The Air Raid in Britain from the Great War to the Blitz (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), introduction. See also Brett Holman, The Next War in the Air: Britain’s Fear of the Bomber, 1908-1941 (London: Routledge, 2017), pp. 23-54.

30 Ariella Freedman, ‘Zeppelin Fictions and the British Home Front.’ Journal of Modern Literature 27: 3 (Winter 2004): pp. 47–62; Barry Powers, Strategy without Slide-Rule (London: Routledge, 1976), p. 51.

31 Grayzel, At Home and under Fire, p. 22.

32 Freedman, ‘Zeppelin Fictions’, pp. 50-52

33 Freedman, ‘Zeppelin Fictions’, p. 50

34 Uri Bialer, ‘The Danger of Bombardment from the Air and The Making of British Military Disarmament Policy 1932-34,’ in Brian Bond and Ian Roy (eds), War and Society; A Yearbook of Military History (New York: Holmes and Meier, 1975), p. 204; Martin Ceadel, ‘Popular Fiction in the Next War, 1918-39.’ in Jon Clark et al. (eds), Culture and Crisis in Britain in the Thirties (London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1979); Christopher Joel Simer, ‘Apocalyptic Visions: Fear of Aerial Attack in Britain, 1920–1938’ (PhD diss., University of Minnesota, 1999).

35 Bialer, ‘The Danger of Bombardment’, p. 204.

36 Bialer, ‘The Danger of Bombardment’; I. F. Clarke, Voices Prophesying War: Future Wars, 1763-3749 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992); Ceadel, ‘Popular Fiction in the Next War’; Freedman, ‘Zeppelin Fictions’; Grayzel, At Home and under Fire; Simer, ‘Apocalyptic Visions’. The progenitor of fictional iterations of the aerial apocalypse was HG Wells, who envisioned a global ruin wrought by German airships in his 1908 The War in the Air. This serialized novel anticipated, though overstated, the wholesale destruction of civilian targets that would ensue from a global aerial arms race. Wells’ predictions, whilst resonant in the First World War, would come closer to fruition in the bombing campaigns of the Second.

37 John Ferris, ‘Achieving Air Ascendancy: Challenge and Response in British Strategic Air Defence, 1915-40.’ In Peter Gray and Sebastian Cox (eds.), Air Power History: Turning Points from Kitty Hawk to Kosovo (New York: Frank Cass Publishers, 2002), p. 24

38 ‘Wembley Presents the Case for Air Raid Defence’.

39 Priya Satia, ‘The Defense of Inhumanity: Air Control and the British Idea of Arabia.’ The American Historical Review 111:1 (February 2006): pp. 25-27.

40 Satia, ‘The Defense of Inhumanity’, p. 25.

41 David E. Omissi, Air Power and Colonial Control: The Royal Air Force 1919–1939 (Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, 1990).

42 ‘Wembley Presents the Case for Air Raid Defence’.

43 ‘Wembley Presents the Case for Air Raid Defence’.

44 These early pushes for decolonization were formative. However, Britain often retained its outsize influence even in countries to which it had formally granted independence. These tools of control included close economic ties and military connections. See Andrew Thompson (ed.), Britain’s Experience of Empire in the Twentieth Century (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), introduction.

45 The extent to which the empire functioned as a primary actor in the consciousness of the British public is a matter of debate amongst historians, who are divided between those, like John Mackenzie, who argue that the empire remained a fundamental basis of early-twentieth-century British thought and those, like Bernard Porter, who argue that the empire was primarily an abstract concept distinct from everyday British identity. John MacKenzie (ed.), Imperialism and Popular Culture (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1986); Bernard Porter, ‘Popular Imperialism: Broadening the Context.’ The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 39:5 (2011): pp. 833-845, accessed 10 October 2021, doi:10.1080/03086534.2011.629091. For a summary of the debate, see S.J. Potter, ‘Empire, Cultures and Identities in Nineteenth- and Twentieth-Century Britain.’ History Compass, 5 (2007): pp. 51-71, accessed 10 October 2021, doi:10.1111/j.1478-0542.2006.00377.x. However, in the context of public exhibitions like the British Empire Exhibition, John Mackenzie and John McAleer demonstrate that cultural productions, like the performances at Wembley, played a material role in communicating imperial identity British citizens. John McAleer and John M MacKenzie, Exhibiting the Empire: Cultures of Display and the British Empire (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2015).

46 Geppert, Fleeting Cities, p. 162.

47 Sarah Britton, “‘Come and See the Empire by the All Red Route!”: Anti-Imperialism and Exhibitions in Interwar Britain.’ History Workshop Journal, 69 (Spring 2010): pp. 68–89.

48 G.C. Laurence (ed.), British Empire Exhibition, 1925 Official guide (London: Fleetway Press, 1925).

49 ‘Torchlight Tatoo’, The Lancashire Evening Post, August 28, 1924.

50 ‘Torchlight Tatoo’.

51 London Defended, p. 10.

52 The same interdepartmental group who had responsibility for the performances of the Government Pavilion dictated the displays at the Empire Stadium. The Stadium and the Pavilion were seen as part of the same larger government programme. Minutes of meeting discussing government participation in the British Empire Exhibition, August 30, 1923, MT 9/1602, The National Archives, Kew, United Kingdom.

53 London Defended, p. 10.

54 London Defended, pp. 4-6.

55 London Defended, p. 10.

56 Holman, The Next War in the Air, pp. 170-72. Holman argues that the attendance number at Hendon in the first years of the 1920s are evidence of a public interest in the RAF.

57 London Defended, p. 12.

58 Flight, July 7, 1921, p. 456 cited by Brett Holman, ‘Ending Hendon — I: 1920-1922.’ Airminded (blog), November 9, 2011, accessed 10 October 2021, https://airminded.org/2011/11/09/ending-hendon-i-1920-1922/.

59 Holman, ‘Ending Hendon — I: 1920-1922’.

60 The relationship to contemporary politics is evident as Mandatory Iraq, under British colonial control, had been created in 1921.

61London Defended, p. 10.

62 London Defended, p. 10.

63London Defended, p. 11.

64 Geppert, Fleeting Cities, p. 169.

65 The British Empire Exhibition was intended to increase working- and middle-class commitment to empire. Contemporaneous accounts evidence the excitement generated by the possibility of ‘visiting’ all corners of the empire. John Mackenzie argues that the theatre of empire that played out in England, through ‘royal pageantry, warfare, sport, and even architecture,’ was evidence of working-class enthusiasm for the imperial project, John MacKenzie, Propaganda and Empire: The Manipulation of British Public Opinion 1880–1960 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1984). Indeed, Mackenzie identifies Wembley as emblematic of this trend. Though Mackenzie argues for the pervasive awareness of empire within the working-class, the British Empire Exhibition lend some ambivalence to the assertion that imperial entertainment was conducive to imperial identity. Andrew Thompson argues that, in fact, ‘Wembley may reflect a concern about the extent of the public’s ignorance of the empire, or the failure of previous propaganda to fully persuade people of its value,’ in Andrew Thompson, The Empire Strikes Back? The Impact of Imperialism on Britain from the Mid-Nineteenth Century (London: Routledge, 2005), p. 87. Scholars including Bernard Porter and David Cannadine point to how English class systems were determinative of the power structures of Empire in a way that excluded the working-class, Bernard Porter, The Absent-minded Imperialists, pp. 265-66; David Cannadine, Ornamentalism: How the British Saw Their Empire (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001). Jonathan Rose also demonstrates that the lack of knowledge about imperial structures was borne from lack of newspaper access, geographic isolation, and insufficient public education, Jonathan Rose, The Intellectual Life of the British Working Classes (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002), pp. 321–64.

66 The Daily Herald did an ongoing series on the finances and working conditions of the exhibition. See ‘Inhuman Wembley Conditions. Pitiful Tales’, Daily Herald, May 14 1924; ‘Bad Management Somewhere’, Daily Herald. December 8, 1925. The financial burden of the exhibition was also debated in Parliament including the session on December 10, 1925, United Kingdom. Hansard Parliamentary Debates, vol. 189 (1925), pp. 802-836. Sarah Britton also discusses this controversy, Britton, ‘Come and See the Empire’, pp. 76-77.

67 Britton, ‘Come and See the Empire’, pp. 75-77.

68 Cabinet Meeting Notes, April 2, 1924, CAB 23/47/18, The National Archives, Kew, United Kingdom.

69 ‘Big Wembley Strike’, Daily Herald, March 24, 1924.

70 ‘Wembley Menace’, Edinburgh Evening News, April 2, 1924.

71 ‘A Strike Threat’, Sheilds Daily News, April 8, 1925.

72 ‘Big Wembley Strike’.

73 ‘Violence at Wembley’, The Lancashire Daily Post, April 2, 1924.

74 United Kingdom. Hansard Parliamentary Debates, vol. 189 (1925), pp. 802-836

75 ‘Communists at Work, Southampton and Wembley’, The Times, April 2, 1924.

76 ‘Colonial Resoluton’ (Sixth Congress of the Communist Party of Great Britain, Manchester, May 17-19 1924).

77 JR Campbell, ‘Must the Empire Be Broken Up? The Reply to Labour Imperialism’, The Communist Review, 5 (September 1924): pp. 216–24.

78 T.A. Jackson, ‘The Sudan Scandal’, The Communist Review, no. 5 (September 1924): pp. 236-41.

79 Jackson, ‘The Sudan Scandal’, p. 237

80 ‘Industrial Chaos’, The Belfast Telegraph, April 2, 1924.

81 ‘The Wembley Strike: Communists Behind Industrial Trouble’, The Northern Whig and Belfast Post, April 3, 1924.

82 Alex M. Spencer, British Imperial Air Power: The Royal Air Forces and the Defense of Australia and New Zealand between the World Wars (West Lafayette: Purdue University Press, 2020), pp. 117-121.

83 ‘Air Defence’, The Times. March 5, 1924; ‘Air Defence’, The Times, March 12, 1924.

84 Hugh Addison, The Battle of London (London: Herbert Jenkins, 1923).

85 The appearance of the Germans at the end of The Battle of London echoes other invasion scare literature including H.G Well’s The War from the Air (1908) and the earlier Battle of Dorking (1871) by George Tomkyns Chesney.

86 ‘Gift Books’, The Western Morning News and Mercury, November 30, 1923.

87 The Westminster complex had served as Parliament’s home since its creation in the late thirteenth century. The fire that consumed the building the night of October 16, 1834 began in the basement furnaces. That day, two workers had been tasked with the burning of wooden tally sticks, a primitive form of tax records. In October 1834, almost fifty years after they fell out of use, the Treasury finally ordered their destruction. The large fire they created in the basement furnace burned out of control, and by morning the compound was largely destroyed. For a full description see Caroline Shenton, The Day Parliament Burned Down (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012).

88 Caroline Shenton outlines the fear of populist movements in the days after the fire, most notably the Swing rioters, Shenton, The Day Parliament Burned Down, pp. 193-197.

89 The Morning Herald’s description of the fire was syndicated in ‘Friday’s Post. Destruction of the Houses of Lords & Commons by Fire’, Ipswich Journal, October 18, 1834.

90 ‘Destruction of the Houses of Lords & Commons by Fire’.

91 E.P. Thompson, in his classic Making of the English Working Class distinguishes between a ‘mob’ and ‘revolutionary crowd’ in England during the aftermath of the French Revolution; ‘In 18th-century Britain riotous actions assumed two different forms: that of more or less spontaneous popular direct action; and that of the deliberate use of the crowd as an instrument of pressure, by persons ‘above’ or apart from the crowd.’ He goes on to argue that ‘The employment of the ‘mob’ in a sense much closer … ‘hired bands operating on behalf of external interests’ … [and] was an established technique in the 18th century; and—what is less often noted—it had long been employed by authority itself.’ The Morning Herald used both definitions of the word, implying that it was both spontaneous popular uprising and that it was dictated by opposition political groups. E.P. Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class (New York: Vintage Books, 1966), pp. 62-76.

92 In 1831, anti-government demonstrations followed the failure of the House of Commons to pass the Great Reform Act. The prospect of the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act, which would establish punitive workhouse systems and undermine existing welfare opportunities, further galvanized the working population.

93 Grayzel, At Home and under Fire, p. 128.

94 Ferris, ‘Achieving Air Ascendancy’, pp. 24-25.

95 London Defended, pp. 10-11.

96 Jacob F. Field, London, Londoners and the Great Fire of 1666: Disaster and Recovery (London: Taylor and Francis, 2017), p. 145.

97 Rebecca Rideal, 1666: Plague, War, and Hellfire (New York: Thomas Dunne Books/St. Martin’s Press, 2016), p. 212.

98 Adrian Tinniswood, By Permission of Heaven: The Story of the Great Fire of London (London: Cape, 2003), pp. 58-64; The London Gazette, September 8, 1666.

99 Tinniswood, By Permission of Heaven, pp. 58-64.

100 The London Gazette, September 8, 1666.

101 Field, Disaster and Recovery, pp. 15-16.

102 London Defended, p. 16.

103 London Defended, p. 16.

104 Tom Allbeson, ‘Visualizing Wartime Destruction and Postwar Reconstruction: Herbert Mason’s Photograph of St. Paul’s Reevaluated’, The Journal of Modern History, 87:3 (2015): pp. 532-78.

105 ‘War’s Greatest Picture’, The Daily Mail, December 31, 1940.