This session of the Material Witness series saw a range of PhD students meeting in the Wellcome Galleries on Euston Rd. As we introduced ourselves, sat around a long table in the reading room of the galleries, it became apparent that our research topics were as diverse as the eclectic range of objects that surrounded us. From urban soundscapes to mediaeval art, the ukulele and contemporary narratives of those with autoimmune diseases, each topic was intriguing. What we had in common was our self-limiting beliefs regarding our drawing ability.

Artist Adrian Dutton, came prepared for these self-deprecating protestations. Showing us a page in his own sketchbook by his daughter, he reminded us that at some stage we too had been equally uninhibited by self- doubt. Our anxiety is usually due to the unsubtle feedback of a teacher or parent.

As an analogy, Adrian suggested that to tell a child that they were not very good at walking so thereafter should get about by bicycle would be unthinkable and disabling. However, many of us, are disabled by discouragement in terms of our creative expression through drawing. Drawing is also a way of thinking. I was reminded of some quotes from artists, displayed at Tate Modern;

“Drawing is simply a line going for a walk” Paul Klee.

“I draw what I feel in my body” Barbara Hepworth.

“To draw you must close your eyes and sing” Pablo Picasso.

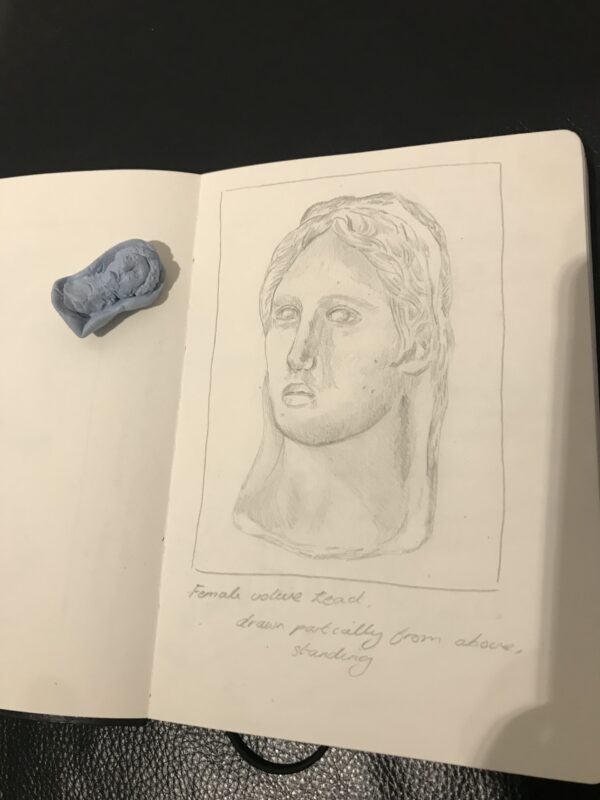

Adrian explained how he, as an artist, uses sketch books as a mode of thinking, in which to “examine, ferment and distil observations and ideas”. He showed us examples from other artists demonstrating how combinations of small sketches, different materials, annotations and notes could be used to develop thoughts.

My own practice- led, medical humanities research on reflective practice and the well-being of healthcare practitioners explores the use of creative methods. Facilitating workshops with doctors, generating positive graphic narratives of care, “Sparkling Moments” I was aware of the self- limiting beliefs of those who rarely draw. I was also aware that most find the process engaging , liberating and joyful. Pencils, rubbers and pens are reminiscent of childhood and play. The empty page is inviting. As the paediatrician and psycho therapist Donald Winnicott hypothesized, in adulthood cultural and creative “spaces” serve a similar role to the “transitional object” of childhood, the favoured teddy bear or blanket. Winnicott considered the safe space offered by play…” shall exist as a resting place for the individual engaged in the perpetual human task of keeping the inner and outer reality separate yet interrelated”[1] p3. Bridget Procter identified three aspects of supervision; the formative (growth), the normative (monitoring) and restorative (support).[2] My research explores the “restorative”, resting element of creative practice in supervision. At the Wellcome galleries we were exploring the “formative” element of drawing.

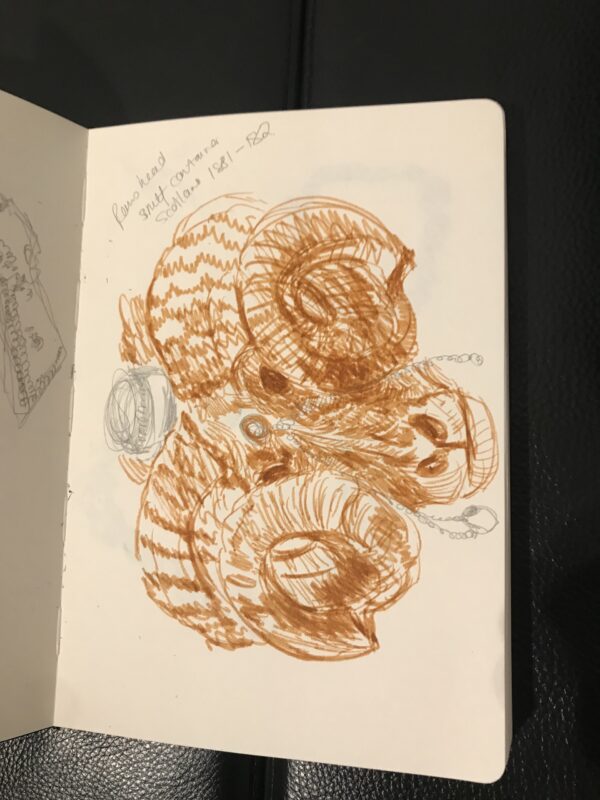

The use of small panels, as recommended by Adrian, to sketch objects from different perspectives reminded me of the use of panels and gutters in sequential art and comics. Opening our new sketchbooks we set off to explore the gallery. The collection of Henry Wellcome was amassed between 1890 and 1936 from across the world, “intended to form a documentary resource that reflects the cultural and historical contexts of health and medicine.” [3] Wellcome collected multiple examples of one object and I was drawn to the glass collection. I sketched the range of shapes and sizes considering their arrangement. My drawings led my thoughts in unexpected directions, the shapes reminiscent of cremation urns, resonated with research I had done on human ashes in glass. The deep blue colour reminded me of my own pieces. The distilling flasks took me back to the chemistry lab, the imperfections and bubbles in the glass, only visible up close, reminded me of my fascination with the process of glass blowing. These unique, imperfect samples contrasted to the uniformity of new, modern flasks such as those suspended from the ceiling of the Wellcome café, uniform, perfect and identical. This led my thought to the history of science, paradigms and the place of serendipity.

I gradually focussed my attention on one object. I had sketched three green elephantine flasks, presumably used for distillation, interested by their similarities and differences. Then focussing on one I was drawn to the junction between the trunk and the body, the round shoulder and the “eye”, embodied metaphors relating to these parts came to mind; “truncated”, “Shouldering the blame”, “an elephant never forgets”. I drew small parts of the flask capturing the relation to its surrounding, its support and the shadows.

I found my annotations took on a poetic form and I recognised new connections between areas of my work and my personal history and connection with glass.

Comparing notes with others over lunch, we shared drawings and insights and discovered that we had all found our thoughts going in surprising directions. We had focussed on unexpected items and gained fresh insights through the process of drawing. Being in close contact with “real” objects had been a very different experience from studying digital images.

In the afternoon we visited the current exhibition “Smoke and Mirrors: the Psychology of Magic”. The exhibition shows how magical performances developed out of efforts to disprove things like spirit photography.

Later revisiting my sketches and the Wellcome digital catalogue I searched online for glass in the collection. My own drawings of a selection of glass eyes, in the collection, shows them nestled and precious in a velvet lined box of the sort that might hold a rare and valuable item of jewellery. They are clustered together like a number of snail shells. Their unseeing pupils searching in different directions.

By contrast the digitised images of glass eyes in the online collection shows them on a white background, more abstract and scientific. The description reads “A selection of glass eyes from an opticians glass eye case. Possibly made by E.Muller of Liverpool.”

While digital sources are valuable for research there are definite benefits to close study of the “real” object and its context. Through the workshop, the effectiveness of drawing as a research process for stimulating thought was affirmed for me and for others in the group. The value of challenging self limiting beliefs and encouraging creativity for human flourishing (one of the foundation principles of coaching practice) was also affirmed for me through the material witness day.

[1] Donald Winnicott Playing and Reality (London, Routledge ,2005)

[2] Bridget Procter Training for the Supervision Alliance; Attitude ,Skills and Intention.(London, Routledge ,2001)

[3] Wellcome Collection https://wellcomecollection.org/works