On the afternoon of 17th May 2019 graduate students across the CHASE consortium gathered at Canterbury Cathedral for the sixth and final Material Witness workshop of the term. An impressive building of international significance, Canterbury has witnessed much since its founding by Augustine in 597, including the murder of Archbishop Thomas Becket in 1170, the first Gothic rebuilding project in England after the fire of 1174, damage sustained during the reformation, and the destruction of its library by an incendiary bomb in 1942 and subsequent reconstruction. Not only is it an exquisitely beautiful example of medieval art and architecture, but an absolute treasure trove of materiality, both in the stones that make up its walls and its rich archival collections.

Guided by Drs David Rundle and Emily Guerry of the University of Kent, the aim of this session was to foster conversations, encourage the discussion of ideas and ways that close encounters with historical sources can inform our understanding of the past, and draw upon Canterbury Cathedral’s rich material history from the medieval period to the modern day.

Emily began our fascinating tour in the cloister, using a Norman ink and wash drawing of the Cathedral waterworks from the Eadwine Psalter (Cambridge, Trinity College, MS R.17.1) as a navigational tool. Once our eyes had adjusted to our copies, we were able to distinguish the existing and lost building structures that made up the fabric of the Cathedral in the twelfth century. Following in its medieval footsteps, Emily lead us around the north of the present-day Cathedral to discover Prior Wybert’s water tower, followed by the infirmary ruins and treasury, visually separating the Romanesque from the Gothic building phases. We then descended into the dark and silent space of the crypt to examine the vestiges of medieval and early modern graffiti, stone carvings and wall paintings that have borne witness to centuries of visitors, before walking north around the precincts to the outbuildings that now form part of the King’s School.

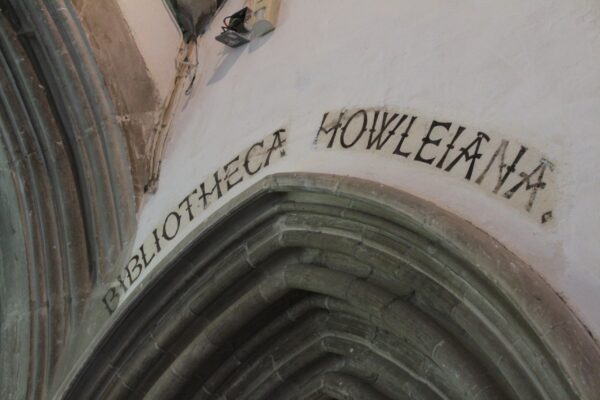

Participants were then welcomed upstairs into the space of the Howley-Harrison Library by Cathedral Librarian Fawn Todd. Built in 1665, the library was renamed after William Howley, who served as Archbishop during the second quarter of the nineteenth century (and coronated Queen Victoria), and Benjamin Harrison, then Archdeacon of Canterbury. It stands much as it once was back then, complete with dark wooden bookcases laden with leather-bound tomes, and a stone fireplace at the far end. Now used as a space for storing some of its collections, Fawn shared her knowledge of the history of the library and placed some rare printed volumes out on display for us to look at.

Looking back at its long history, David then shed light on Christ Church priory’s status as an international centre of learning in the medieval period, with its flourishing scriptorium producing impressive quantities of books. The location of this scriptorium remains unknown, but discussion raised a series of thought-provoking questions that got us all considering the undoubtably complex ‘afterlife’ of its books post-production. These considered the features of library spaces, book production, usage, medieval and early modern literacy levels, books as highly mobile objects, provenance, conservation, and possible intellectual exchange between workshops.

It was then time for us to make the transition from the ‘old’ to ‘new’ space, to the purpose-built library and archives built in 1954 that replaced the earlier Victorian building destroyed during the war. Fortified by a selection of tea, coffee and biscuits, the day concluded with an exciting opportunity for us to spend time with some of Canterbury’s wonderful manuscripts – a very special treat! David described each of their paleographical and codicological features, with evidence of rubbing, fingerprints, marginal annotations, iconoclasm, and some fragmented bifolia survivals (repurposed as binding for many years) demonstrating the long and complicated lives of each manuscript, and what their stories can tell us. After all the volumes were safely returned to storage at the end of the day, several of us made our way over to one of Canterbury’s oldest pubs (in true pilgrim style), where conversations continued over a glass or two.

The day was not only thought-provoking and insightful, but thoroughly enjoyable. Interactions with Canterbury Cathedral’s old, new, and lost spaces, bolstered by vibrant and interdisciplinary teaching and discussion on the past and present lives of its buildings, led us to reflect on the ephemerality of repository spaces and their ever-changing collections. It was a fantastic opportunity to engage with the hidden material treasures of Canterbury Cathedral’s Library and Archives, with each object bearing witness to tell their own unique story: a brilliant way to end the session and, indeed, the term.