The substantial holdings of works by Girolamo Francesco Maria Mazzola, known as Parmigianino (1503-1540), at The Courtauld have inspired us to develop a collaborative project with current and former postgraduate students, curators, and members of the Conservation department. This remarkable body of works by Parmigianino includes two paintings, twenty-four drawings, and a group of prints, either executed by the artist himself or in collaboration with others. As a printmaker, Parmigianino is thought to be the first to experiment with etching in Italy and was a pioneer of the chiaroscuro woodcut technique.

Parmigianino’s refined and graceful compositions were greatly appreciated by his contemporaries. Fundamentally a draftsman at heart, the artist drew relentlessly during his relatively short life, and around a thousand of his drawings have survived. Among the works in this display are studies for his most ambitious projects, such as the painting of the Madonna of the Long Neck and the frescoes of the church of Santa Maria della Steccata in Parma, Italy.

The latter was the final and most important commission of his life, and should have been his triumphal homecoming. Instead, Parmigianino became entangled in his experimental processes and failed to complete it, leading to his brief imprisonment for breach of contract. In his biography of the artist, Giorgio Vasari (1511-74) attributed Parmigianino’s failure to complete this major project to his growing involvement in vain alchemical practices. There is no documentary evidence for this accusation; Vasari’s claim might derive instead from Parmigianino’s experimentation with acids in his activity as an etcher.

In preparation for this display and its catalogue, new photography and technical examination have been carried out on all the works, revealing two previously unknown drawings, hidden underneath their historic mounts. Such analyses have also helped to better identify connections between some of the drawings and the finished paintings for which they were conceived.

This display was curated by Ketty Gottardo, Martin Halusa Curator of Drawings, and Guido Rebecchini, Reader in Sixteenth-Century Southern European Art. A product of the Covid-19 pandemic, this project stemmed from the need to be together as a community, albeit virtually, discussing and exploring a subject of common interest, while deepening our knowledge of Parmigianino’s art. A truly collaborative project, the display and its catalogue shed light on an artist who approached every technique with unprecedented freedom and produced innovative works studied and admired by artists and collectors for centuries thereafter.

“Never happier than when doodling”

by Grant Lewis

As Parmigianino became engrossed in his large-scale commissions, he spent more and more time drawing. In many cases he devised far more ideas than he could possibly use, producing a slew of leftover proposals that could be developed independently. Further designs were probably made for their own sake rather than for any commission, and still more ideas grew out of these compositions to become independent motifs. The constant interaction of fresh scribbles and loose ends fired his imagination with new ideas for compositions. In the words of one scholar, Parmigianino was “never happier than when doodling”.

Parmigianino had several options for developing his own projects. Some became prints, whilst others were worked up as drawings. At a time when drawings were only rarely collected, Parmigianino was known to several patrons who showed an early interest in acquiring works on paper, and it is possible that he made his more finished creations with such an audience in mind. Others may have been made purely for the artist himself and, in any case, there can be little doubt that he chose subjects that interested him.

This is surely true of a refined red-chalk depiction of the Death of Dido – one of a handful of standalone drawings at The Courtauld that focuses on a single female figure. The choice of a classical subject was far from uncommon. Be it Lucretia, Thisbe or Dido, Parmigianino seems to have been especially intrigued by ancient tales of female suicide; he often made similar, carefully worked drawings of these protagonists, like meditations on a common theme.

Another, comparatively novel, realm that fascinated Parmigianino was the genre scene. Many often highly-finished drawings of daily life survive from his hand, and once again his attention was drawn to solitary women. One of the best-known examples of this type is a drawing of a Woman seated on the ground, her left hand supporting her head, a design that Parmigianino converted into an etching. The scene’s calm simplicity is a world away from the tragedy in the Death of Dido, but in many respects the two drawings have more in common than might initially appear. For a start, the seated woman’s pose may derive from a classical relief Parmigianino could have seen in Rome, but the sheets also share a sensitivity to narrative that pervades so many of these independent explorations. Such was its success that for centuries viewers were tempted to look for more meaning in the Woman seated on the ground than the artist surely intended.

The Conversion of Saul: a tale of two cities

by Genevieve Verdigel

The Sack of Rome in 1527 by mutinous Imperial troops and mercenaries saw Parmigianino and other artists active in the city disperse across the Italian peninsula. Parmigianino fled to Bologna, where he resided until 1530. Despite being new to the city, the artist quickly gained clients and completed several significant commissions. Among these were the paintings of Saint Roch and a Donor (Bologna, church of San Petronio), Madonna of the Rose (Dresden, Gemäldegalerie) and the Conversion of Saul (Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum). The latter painting is known to have been commissioned by Andrea Bianchi, Professor of anatomy at the University of Bologna, who hung it in his residence.

In The Courtauld’s collection are two double-sided sheets depicting the Conversion that offer valuable insights into Parmigianino’s use of drawings within his fulfilment of commissions. The black chalk study for the Conversion is of particular importance because it closely corresponds to the composition that Parmigianino chose for the final painting. It can be described as an exploratory sketch, with the horse and fallen body of Saul – who would become Saint Paul – rendered through swift lines and abbreviated forms. The same subject also appears in a monumental sheet, which features two powerful studies of the biblical episode on both the recto and verso. These highly finished drawings were, however, most likely produced for an unrealised project that Parmigianino appears to have designed for the Papal rooms in the Vatican Palace shortly after his arrival in Rome in 1524. As such, they show how the artist derived inspiration from earlier projects in commissions that he fulfilled across his career.

Drawing in Paint

by Esme Garlake

The freedom of mark-making in Parmigianino’s drawings often bears little resemblance to his highly finished painting technique. In perhaps his most famous painting, The Madonna of the Long Neck (Florence, Gallerie degli Uffizi), the glossy fabrics and porcelain flesh of the figures have defined our understanding of Parmigianino as a painter. Yet when we consider his paintings alongside his drawings, we better understand how the exceptional finish that Parmigianino could achieve in paint only forms one part of his diverse and experimental oeuvre.

Behind every painting by Parmigianino, there are innumerable drawings. These were used to experiment with – and to flesh out – a range of compositional and stylistic ideas. Parmigianino often covered a sheet of paper with myriad sketches, depicting many different subjects as if doodling. At times, these sketched pages give the impression of an artist who did not draw simply to reach a final painted composition, but rather for the sake of drawing as artistic experimentation. By only looking at Parmigianino’s finished paintings, one would ignore the complexities of his artistic process and experimental outlook.

The Virgin and Child is one of a few paintings that encapsulates these nuances. Painted around the time the artist moved to Bologna from Rome in 1527, the painting’s brushwork is remarkably loose, as if the artist were drawing in paint. Parmigianino approached this ‘unfinished’ sketch with the same freedom with which he made his drawings. Notably, he did not create an underdrawing, but applied the paint straight onto the canvas from the start. The painting not only showcases Parmigianino’s confidence as an oil painter, but also his desire to challenge the traditional hierarchy between drawing and painting.

Chiaroscuro, wax, and needles: Parmigianino and the printmaking world

by Jasmine Clark

Although small in output, Parmigianino’s printmaking experiments had considerable influence across Italy. He was the first Italian artist to recognise the potential of etching, freely scratching new compositions onto waxy ground to mimic the appearance of drawing. One of the most ambitious of Parmigianino’s eighteen surviving etchings, Entombment facing right, is held at The Courtauld. It is the amended, reversed version of an earlier print that was replaced when the plate suffered corrosion damage.

Parmigianino revisited this composition, playfully experimenting by reversing the print again, elevating Christ’s tomb and Joseph’s arm, and using a thicker etching needle. He explored some of these compositional changes in a pen and ink drawing in The Courtauld’s collection (image below). Especially visible is the movement of Joseph’s uplifted arm, now marred by a blur of overlapping marks or pentimenti. The drawing’s verso, which is smudged with stains from the printer’s ink, gives a rare glimpse into Parmigianino’s workshop where ideas flowed from one technique to another.

Inspired by his experiments with etchings, Parmigianino collaborated with the engraver Antonio da Trento while in Bologna (1527-1530). Augustus and the Tiburtine Sibyl is an example of the virtuoso chiaroscuro woodcut prints they produced together. Unlike etching, the chiaroscuro woodcut technique could capture the subtle tonal effects that Parmigianino strove to achieve. Here, Antonio employed two woodblocks, a line block of grey to create vivid outlines and a tonal block of light blue to confer volume.

The woodcut depicts Augustus, the first Roman emperor, recognising the higher power of Christ. Through this tale, Parmigianino was perhaps warning the current Holy Roman Emperor Charles V not to underestimate the Church’s power. Of the several studies for the print, the most revealing is a now lost red chalk drawing, recorded in an etching by Francesco Rosaspina (1762-1841). This work shows that the figures in the background were downsized, and the Virgin and angels were added at a later stage.

The fruitful collaboration ceased when Antonio stole Parmigianino’s drawings, woodblocks and plates and fled from Bologna, an episode which gives us a good indication of the prints’ commercial success.

Parmigianino at Santa Maria della Steccata: an unfinished business

by Alexander Noelle

In 1531, upon returning to Parma, Parmigianino received the most important commission of his final years: to paint in fresco the vault and eastern apse of the newly constructed church of Santa Maria della Steccata. This prestigious appointment should have marked a triumphal homecoming for the artist. After a decade of postponements and rising tensions, however, it culminated in a devastating fallout when the confraternity of the church had the artist imprisoned for breach of contract, after which Parmigianino fled to a nearby town, Casalmaggiore, where he died shortly thereafter.

The plethora of preparatory studies reveal Parmigianino’s tireless experimentation with the design of the decoration – from the smallest motifs to the largest elements – perhaps explaining the delays that curtailed the completion of many of the frescoes themselves. One such drawing, the double-sided Female Figure, demonstrates his continuous exploration of forms and poses. While neither side of this sheet is a direct study for any specific figure, the two serpentine nudes are associated with Eve and several other female figures depicted on the ceiling of the church.

By the time he was dismissed, Parmigianino had frescoed the jewel-like barrel vault, including decorative framing registers embellished with golden grotesque-like designs of crayfish and crabs interlaced with floral patterns. A related drawing, depicting a crayfish in scrupulous detail, is surely the result of first-hand study. It illustrates Parmigianino’s interest in capturing even the smallest details in preparation for paintings that would ultimately be placed far above the heads of viewers.

When Parmigianino was forced out of the commission, he had not begun painting the immense apse over the altar, designated to depict the Coronation of the Virgin as the capstone of the project. One of the extant studies shows the artist attempting to define the overall composition of the dynamic scene, which was complicated by the curved edges and rounded foreshortening of the dome. In exile, Parmigianino clung to the possibility of returning to complete the Coronation, but his entreaties were in vain; after his untimely death in 1540, another artist would complete it.

Beneath the surface: Technical examinations reveal two new drawings by Parmigiano

by Jasmine Clark and Kate Edmondson

Technical examinations conducted on all the drawings in The Courtauld’s collection revealed two new drawings, hidden under their historic mounts. To preserve fragile sheets, collectors in the past would affix their drawings onto thicker mounts, which allowed for easy handling. There is no doubt that these sheets have survived to the present day because of this practice. However, it has meant that the drawings on the reverse of these sheets could no longer be seen, until now.

Hidden by its secondary support, the first discovery was found on the reverse of the Study for the Coronation of the Virgin for Santa Maria della Steccata, Parma. Infrared reflectography allowed us an unencumbered view of the male nude drawn on the back of the sheet. Depicted frontally with an arm outstretched, the partial study seems to illustrate ideal human proportions. It is likely Parmigianino had originally portrayed the figure in a full standing position, but the sheet was subsequently trimmed to frame the Coronation. Close up, the crumbly-looking soft lines and the tonal shading strongly suggest the use of chalk or charcoal.

The second long-lost drawing was identified when some faint lines were noticed showing through the lower register of Head of a young woman looking to the right. Due to the thickness of the mount, transmitted light (light shown through from behind the sheet) initially did not reveal more information about the drawing on the verso. However, by using UV and infrared light, and turning the sheet 90 degrees to the right, these subtle undulating marks suddenly began to make sense: they form the profile of a bearded man, drawn on the reverse of the sheet. It is now possible to see clearly the figure’s slightly open mouth and bald pate. These surviving marks seem broken and fluid, indicating that ink was probably used.

Photographs of works from The Courtauld’s collection © The Courtauld

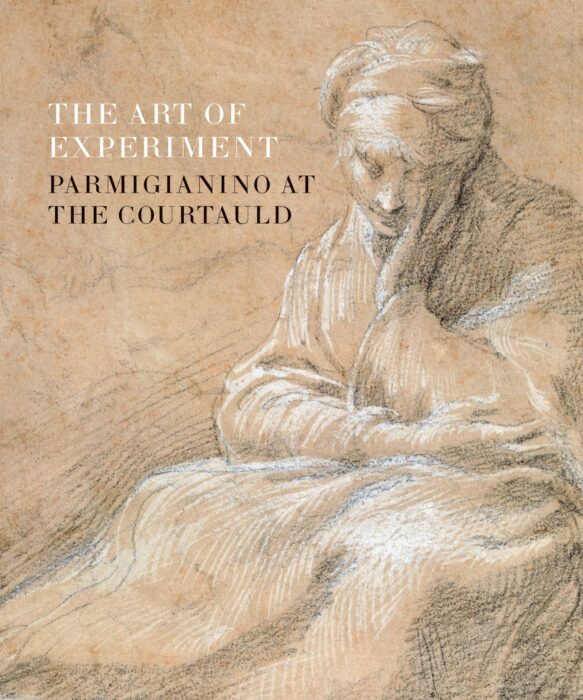

Now on sale: Parmigianino Exhibition Catalogue

A perfect accompaniment for the newly opened drawings exhibition The Art of Experiment: Parmigianino at The Courtauld, this catalogue details works including his famous and enigmatic painting of the Virgin and Child, as well as drawn studies for his most ambitious projects such as the Madonna of the Long Neck and the frescoes of the church of Santa Maria della Steccata in Parma.