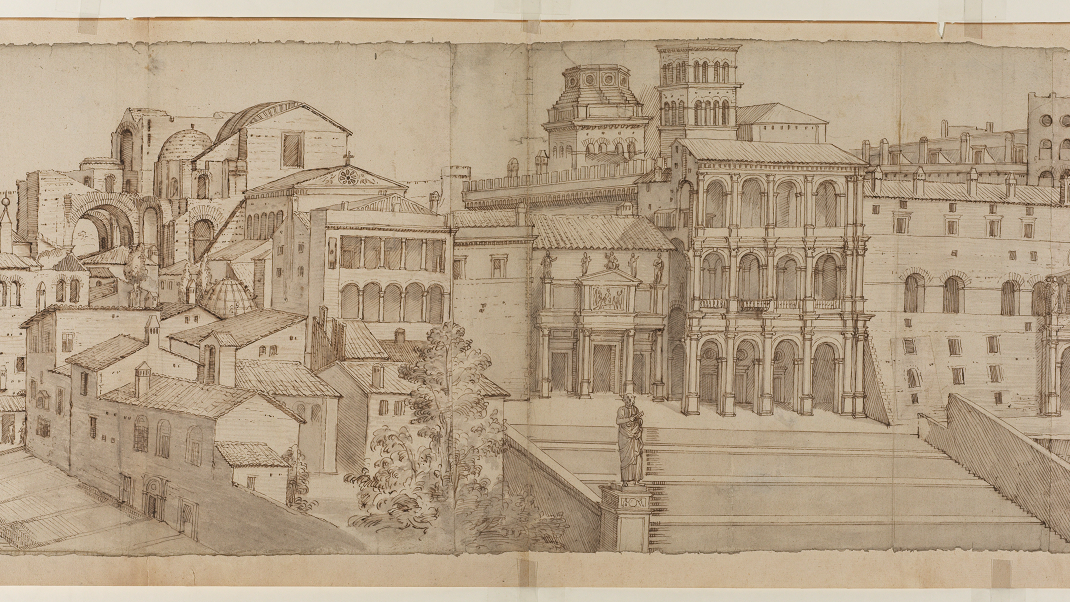

In the sixteenth century, Rome underwent a thorough process of re-fashioning in response to the papacy’s need to assert its authority and legitimacy in the face of challenges from abroad, including the rise of Protestantism, as well as shifts in political dynamics in Italy. Streets, squares and buildings were created which could match the grandeur of ancient ruins and the accounts of the imperial city found in the literary works of ancient authors such as Pliny and Suetonius. Popes including Julius II (reigned 1503-1513) and Paul III (reigned 1534-1549) deliberately fashioned their own public image as Christian counterparts of Julius Caesar or Augustus and actively cultivated the ideology of the Renovatio Imperii, or renewal of empire. Artists such as Raphael and Michelangelo contributed to create such new representations of power. Largely as a result of papal patronage, artists and visitors increasingly flocked to Rome to admire both the ancient monuments – witnesses to the greatness of ancient Rome – and the modern works which rivalled those antique achievements in scale and ambition. In turn, itinerant artists working in cities and courts in Italy and Northern Europe disseminated the unique style that the deep engagement with antiquity had fostered in Rome. While some artists turned to the visual conventions of ancient Rome to produce highly politicized art, including triumphal arches, such as that by Perin del Vaga (cat.), which were aimed at modern-day rulers who saw themselves as new Caesars, other artists found in Rome a world of loss and nostalgia. a melancholic reflection on the transience of history and the decline of civilizations. The view of the new basilica of St Peter in construction encapsulates both the staggering ambition of the project, which took ca. 85 years to complete, and the precarious and fragmentary nature of human achievements.

Join and Support

We care for an outstanding art collection, advance the study and conservation of visual art, and share it through acclaimed exhibitions. Your support helps us inspire new ways of seeing and thinking about art.

Courtauld Gallery

The Courtauld Gallery is home to one of the greatest collections of art in the UK and an annual programme of focused exhibitions, displays and contemporary commissions. All housed in a beautiful human-sized gallery at Somerset House.

Courtauld Institute

The Courtauld Institute is a research-led, independent college of the University of London, offering world–renowned programmes in the history, conservation, curation and business of art.